1 Department of Cardiology, Centre Hospitalier General Victor Jousselin de Dreux, 28100 Dreux, France

Abstract

Cardiac masses pose a significant diagnostic challenge, requiring a structured imaging-based approach. Echocardiography represents the first-line and most essential diagnostic tool, providing a rapid, non-invasive, and cost-effective method for detecting and characterizing intracardiac lesions. While metastatic involvement is the most frequent cause of secondary cardiac masses, the primary tumors are predominantly benign. However, distinguishing between tumors, thrombi, and pseudotumors often necessitates advanced imaging techniques, such as cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or computed tomography (CT). Meanwhile, in addition to the diagnostic role, imaging techniques are essential for risk stratification and guiding therapeutic decisions. Thus, a multidisciplinary approach integrating multiple imaging modalities is crucial for optimizing patient management and improving outcomes.

Keywords

- cardiac tumors

- cardiac thrombi

- echocardiography

- cardiac magnetic resonance imaging

- computed tomography

- positron emission tomography

- multimodality imaging

- tissue characterization

- diagnostic algorithms

- emerging technologies in cardiac imaging

Cardiac masses are a diverse group of lesions that pose significant diagnostic challenges in clinical practice. Although relatively uncommon, they encompass a wide range of conditions, including primary cardiac tumors, metastatic disease, thrombi, and benign pseudotumors. Accurate diagnosis is essential, as it guides appropriate management and helps determine prognosis [1, 2].

Primary cardiac neoplasms are notably most often benign, with myxomas representing the most prevalent subtype [3]. These tumors typically manifest as pedunculated masses originating in the left atrium and may present with clinical features related to intracardiac obstruction, systemic embolization, or nonspecific constitutional symptoms. In contrast, primary malignant cardiac tumors—most commonly sarcomas—exhibit markedly aggressive behavior, frequently characterized by infiltrative growth and a sessile morphology.

Metastatic involvement of the heart is far more common than primary cardiac tumors. Secondary cardiac tumors arise from malignancies elsewhere in the body, most often originating from the lungs, breast, melanoma, lymphoma, or renal cell carcinoma.

These metastases may affect any cardiac chamber or structure, frequently presenting as multiple lesions.

Thrombi constitute another significant category of intracardiac masses that require meticulous differentiation from neoplastic lesions. These formations commonly arise in individuals with predisposing conditions such as atrial fibrillation, mitral valve pathology, ventricular dysfunction, or hypercoagulable states. Accurate identification of thrombi is essential, as prompt initiation of anticoagulant therapy may effectively prevent severe thromboembolic events.

Advancements in cardiac imaging have greatly improved the ability to evaluate cardiac masses. Transthoracic echocardiography remains the first-line imaging modality due to its accessibility, ease of use, and safety. However, more advanced techniques, such as cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMR) and computed tomography (CT), provide superior tissue characterization and play a critical role in differentiating between tumors, thrombi, and normal cardiac structures.

Given the complexity of cardiac masses, a multidisciplinary approach is essential. Collaboration between cardiologists, radiologists, pathologists, and oncologists ensures precise diagnosis, individualized risk assessment, and optimal treatment planning. This integrated strategy ultimately enhances patient outcomes and improves the quality of care for individuals with cardiac masses.

We conducted a targeted review of the literature on cardiac mass imaging, focusing on publications between January 2020 and December 2024. Using PubMed, we combined MeSH terms such as “Heart Neoplasms/diagnostic imaging”, “Echocardiography”, “Magnetic Resonance Imaging”, “Tomography, X-Ray Computed”, “Positron-Emission Tomography”, and “Thrombosis/diagnostic imaging” with relevant free-text keywords including “cardiac masses”, “cardiac tumors”, and “multimodality imaging”. Boolean operators allowed the query to be refined to reflect clinical imaging applications.

Two reviewers independently screened the initial 312 articles, removing 27 duplicates before systematic evaluation. We included original peer-reviewed studies and systematic reviews that reported diagnostic characteristics or compared imaging modalities for cardiac masses in adult patients. We excluded case reports, conference abstracts, and non-English articles. Given the distinct diagnostic considerations in these settings, we also excluded pediatric studies and those lacking imaging-pathology correlation.

Of the remaining 285 studies, 151 full-text articles were reviewed in detail. Fifty-three met our inclusion criteria. The studies showed significant heterogeneity in patient age (18–95 years), symptoms (ranging from incidental findings to severe presentations), and comorbidities. Imaging protocols varied as well: echocardiography studies ranged from standard two-dimensional (2D) exams to advanced three-dimensional (3D) or contrast-enhanced approaches; CMR protocols differed in sequence type, contrast use, and field strength.

Study quality was assessed using the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool, focusing on patient selection, index tests, reference standards, and study flow. Discrepancies between reviewers were resolved by consensus, with occasional involvement of a third reviewer. We used the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) framework to evaluate the overall strength of the evidence, accounting for study design, consistency of results, directness of evidence, and risk of publication bias.

Where available, we extracted information on the clinical impact of imaging, such as changes in treatment decisions, diagnostic confidence, and links to patient outcomes. We also noted data on cost-effectiveness, accessibility, and the need for specialized training, as these factors often influence how imaging modalities are adopted in practice.

The variability observed in protocols and reference standards precluded meta-analysis. However, this diversity offered insight into the performance of imaging techniques across a wide range of clinical scenarios. The limited sample sizes in many studies, while reflecting the inherent rarity of cardiac masses, underscore the ongoing need for larger, standardized investigations.

Cardiac masses represent a heterogeneous group of lesions with distinct etiologies, ranging from benign primary tumors to malignant neoplasms, metastatic disease, thrombi, and tumor-like pseudomasses. Accurate classification is essential to guide therapeutic management and determine prognosis. Primary cardiac tumors are rare, with an incidence of 0.0017% to 0.33% in autopsy series, among these, 75% are benign, with myxomas accounting for approximately 50% of all cases [4, 5]. These benign tumors, as described by Butany et al. (2005) [6], typically manifest with symptoms related to obstruction, embolization, or constitutional effects.

In contrast, primary malignant tumors, predominantly sarcomas, exhibit more aggressive behavior and poor prognosis. Tyebally et al. (2020) [7] highlighted in their state- of-the-art review on cardiac tumors that these malignant neoplasms often infiltrate adjacent structures and may cause arrhythmias, pericardial effusion, or heart failure with a median survival of only 6 to 12 months for patients with unresected cardiac angiosarcomas.

Secondary (metastatic) cardiac tumors are significantly more frequent than primary forms. Haider et al. (2023) [8] reported that cardiac metastases are 20 to 40 times more common than primary tumors. The most frequent primary sites include the lungs, breasts, melanomas, lymphomas, and renal cell carcinomas. These metastases may involve the pericardium, myocardium, or endocardium, with clinical manifestations varying according to location and extent of involvement [9].

Pseudomasses, such as normal anatomical variants, hypertrophy, or vegetations, can sometimes mimic true cardiac masses. According to Kurmann et al. (2023) [10], these entities account for up to 15% of “masses” initially identified on echocardiographic examinations. Their recognition is important to avoid unnecessary interventions.

The distinction between tumors and thrombi is crucial, as their management differs significantly. As demonstrated by Mousavi et al. (2019) [11], while tumors may require surgical intervention or chemotherapy, thrombi often resolve with appropriate anticoagulation. Therefore in the 2022 ESC Guidelines for the management of patients with cardiac tumors, the importance of accurate diagnostic assessment using complementary imaging modalities to differentiate these entities is emphasized [12].

This detailed classification of cardiac masses not only guides differential diagnosis but also influences the selection of imaging modalities and therapeutic strategies, as will be discussed in the following sections. The typical imaging features of different cardiac mass types are summarized in Table 1, which provides a comprehensive overview of echocardiographic, MRI, CT, and Positron Emission Tomography (PET) characteristics for each pathological entity.

| Mass type | Echo features | MRI characteristics | CT features | PET activity | Clinical context |

| Myxoma | • Pedunculated | • T2 hyperintense | • Soft tissue density | • Low FDG uptake | • Middle-aged females |

| • Left atrial | • Heterogeneous enhancement | • Calcification rare | • Variable intensity | • Embolic symptoms | |

| • Mobile | • Narrow stalk attachment | • Well-defined borders | • Constitutional symptoms | ||

| • Heterogeneous echo | |||||

| Thrombus | • Laminated appearance | • No enhancement (LGE) | • Low attenuation | • No FDG uptake | • AF, valvular disease |

| • Avascular on contrast | • T1 variable | • No enhancement | • Cold defect | • Wall motion abnormality | |

| • Associated with wall motion abnormality | • T2 intermediate | • Filling defect pattern | • Anticoagulation indication | ||

| Sarcoma | • Sessile attachment | • T2 hyperintense | • Irregular enhancement | • High FDG uptake | • Young adults |

| • Infiltrative borders | • Heterogeneous enhancement | • Invasion of adjacent structures | • Intense activity | • Rapid growth | |

| • Multi-chamber involvement | • Necrotic areas | • Heterogeneous density | • Systemic symptoms | ||

| Metastases | • Multiple lesions | • Variable signal intensity | • Multiple nodules | • High FDG uptake | • Known primary cancer |

| • Variable locations | • Ring enhancement | • Pericardial effusion | • Multiple foci | • Dyspnea | |

| • Pericardial involvement | • Multiple lesions | • Lymphadenopathy | • Pericardial effusion | ||

| Fibroma | • Intramyocardial | • T1/T2 hypointense | • Calcification present | • No FDG uptake | • Pediatric patients |

| • Homogeneous | • Minimal enhancement | • “Popcorn” pattern | • Arrhythmias | ||

| • Well-circumscribed | • Calcification common | • Well-defined | • Often asymptomatic | ||

| Lipoma | • Echogenic | • T1 hyperintense | • Fat attenuation (–50 to –150 HU) | • No FDG uptake | • Elderly patients |

| • Well-circumscribed | • Suppressed on fat-sat | • Homogeneous | • Cold lesion | • Often incidental | |

| • Compressible | • No enhancement | • Well-defined | • Rarely symptomatic |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; CT, computed tomography; FDG, PET, positron emission tomography fluorodeoxyglucose; LGE, Late gadolinium enhancement; AF, atrial fibrillation.

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE) remains the cornerstone of initial assessment for suspected cardiac masses due to its wide availability, non-invasiveness, and cost- effectiveness [5]. It enables real-time visualization of cardiac chambers and mass mobility, offering immediate diagnostic insight in acute or symptomatic settings. Recent studies have demonstrated that contemporary TTE achieves a sensitivity of approximately 87% and specificity of 89% for detecting cardiac masses [13, 14]. For primary cardiac tumors specifically, TTE sensitivity reached 93% for masses

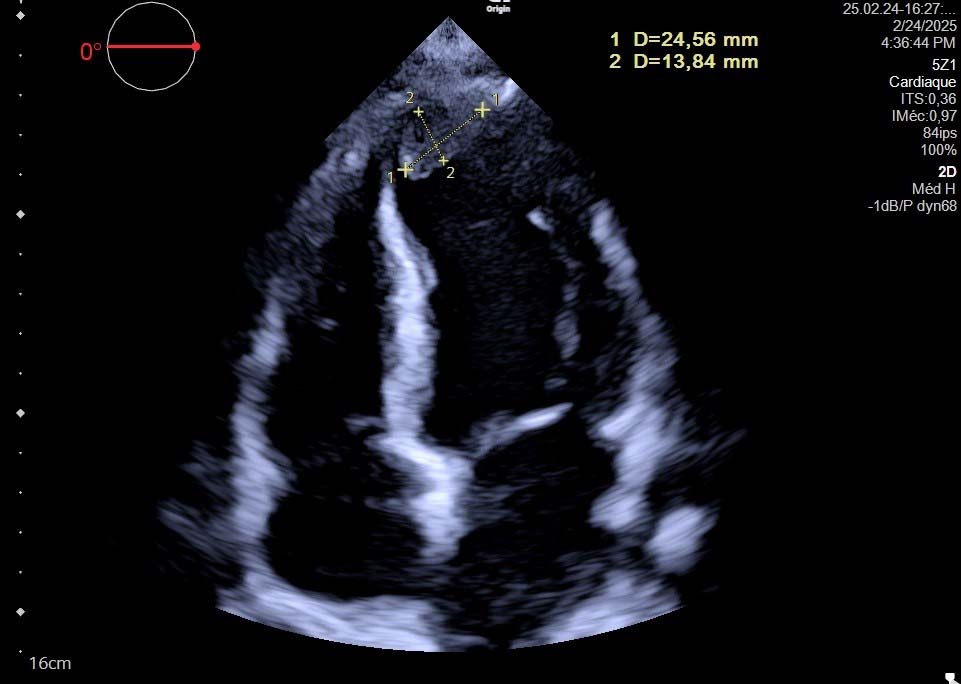

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Transthoracic Echocardiography - Apical Four-Chamber View Showing Left Ventricular Apical Thrombus. Two-dimensional echocardiography demonstrates an echogenic mass at the left ventricular apex (measured dimensions: 24.56 mm

Three-dimensional echocardiography has refined mass assessment by providing volumetric reconstructions with 62% better spatial resolution than standard 2D imaging. Recent studies reported that 3D-TTE modified the diagnosis in approximately 25% of cases and significantly impacted surgical planning over one-third of patients with pedunculated tumors by accurately defining attachment points and spatial relationships [13]. This technique demonstrated 95% concordance with surgical findings regarding tumor attachment sites, compared to 76% for 2D-TTE.

Transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) offers superior spatial resolution (

Contrast-enhanced echocardiography, utilizing intravenous microbubble agents, enhances endocardial border definition and enables assessment of mass perfusion. Wang et al. (2024) [14] demonstrated that contrast echocardiography improved mass detection compared to non-contrast studies and correctly identified thrombi as perfusion defects with 97.7% sensitivity. In their series of 145 patients, contrast enhancement patterns correctly predicted mass histopathology with 96.6% diagnostic accuracy, with significant differences in time-to-peak enhancement between benign and malignant tumors.

Paolisso et al. (2023) [15] identified specific echocardiographic markers with high diagnostic value in a prospective study of 286 patients. They found that the combination of irregular borders, heterogeneous echogenicity, and broad-based attachment predicted malignancy with 87.5% accuracy. Conversely, homogeneous echogenicity, narrow stalk attachment, and high mobility were associated with benign tumors (91% specificity for myxomas when all three features were present).

Kurmann et al. (2023) [10] analyzed outcomes of incidentally discovered cardiac masses and proposed a risk-stratified approach to subsequent management. Their data showed that masses with high-risk echocardiographic features (infiltrative growth, involvement of

Implementation of their structured algorithm reduced unnecessary advanced imaging and expedited treatment for high-risk masses.

Despite these advances, echocardiography has limitations in tissue characterization, with accuracy rates of only 57–78% for specific histological diagnosis [13, 15]. While certain sonographic features may suggest specific diagnoses, advanced imaging modalities are often required for definitive characterization, particularly for complex or atypical masses.

CMR has emerged as the gold standard for evaluating cardiac masses due to its superior soft tissue contrast and multiparametric assessment capabilities [16, 17]. A comprehensive study by Pazos-López et al. (2014) [18] demonstrated that CMR achieved a diagnostic accuracy of 79% for distinguishing between benign and malignant lesions. This exceptional performance underscores the value of CMR as a cornerstone in cardiac mass evaluation. The study further demonstrated that CMR findings directly influenced management decisions in 78% of cases, resulting in significant changes to the initial treatment plan in approximately one-third of patients.

The diagnostic strength of CMR lies in its ability to characterize tissue through multiple sequences, each providing complementary information for a comprehensive evaluation. Haider et al. (2023) [8] demonstrated in their landmark study that the integration of these sequences significantly enhances diagnostic accuracy and provides valuable prognostic information. Recent research have shown that CMR-derived tissue characteristics were independent predictors of adverse events, with significant hazard ratios for masses exhibiting specific enhancement patterns.

3.2.2.1 Anatomical and Tissue Characterization Sequences

T1-weighted sequences effectively delineate anatomy and are particularly useful for identifying fat-containing masses such as lipomas, which appear hyperintense due to their short T1 relaxation time. These sequences also provide excellent definition of mass morphology, delineating precise borders and relationships with adjacent structures. T1-weighted sequences with fat suppression can further enhance diagnostic specificity by confirming the presence of adipose tissue within masses, a feature characteristic of certain entities such as lipomas or liposarcomas.

T2-weighted imaging helps assess fluid content within masses, with cysts and myxomas typically displaying high signal intensity due to their high water content. This sequence is particularly valuable for differentiating solid from cystic components and for identifying edematous changes within solid masses. Recent studies demonstrated that T2 signal intensity ratios (comparing mass signal to skeletal muscle) greater than 3.0 were highly specific (92%) for myxomas and cysts [11, 18].

Additionally, T2-weighted sequences with fat suppression can highlight areas of inflammation or edema, providing insights into the biological activity of the mass.

First-pass perfusion sequences evaluate the vascularity of masses by tracking the initial passage of gadolinium contrast through the cardiac chambers and myocardium. These dynamic sequences capture contrast enhancement patterns, with malignant tumors generally showing earlier and more pronounced enhancement compared to benign lesions or thrombi. Quantitative analysis of perfusion parameters, including time-to-peak enhancement and wash-in/wash-out kinetics, provides additional diagnostic information. Malignant masses typically demonstrate rapid enhancement with early washout, while benign lesions often show more gradual enhancement patterns.

3.2.2.2 Advanced Tissue Characterization Techniques

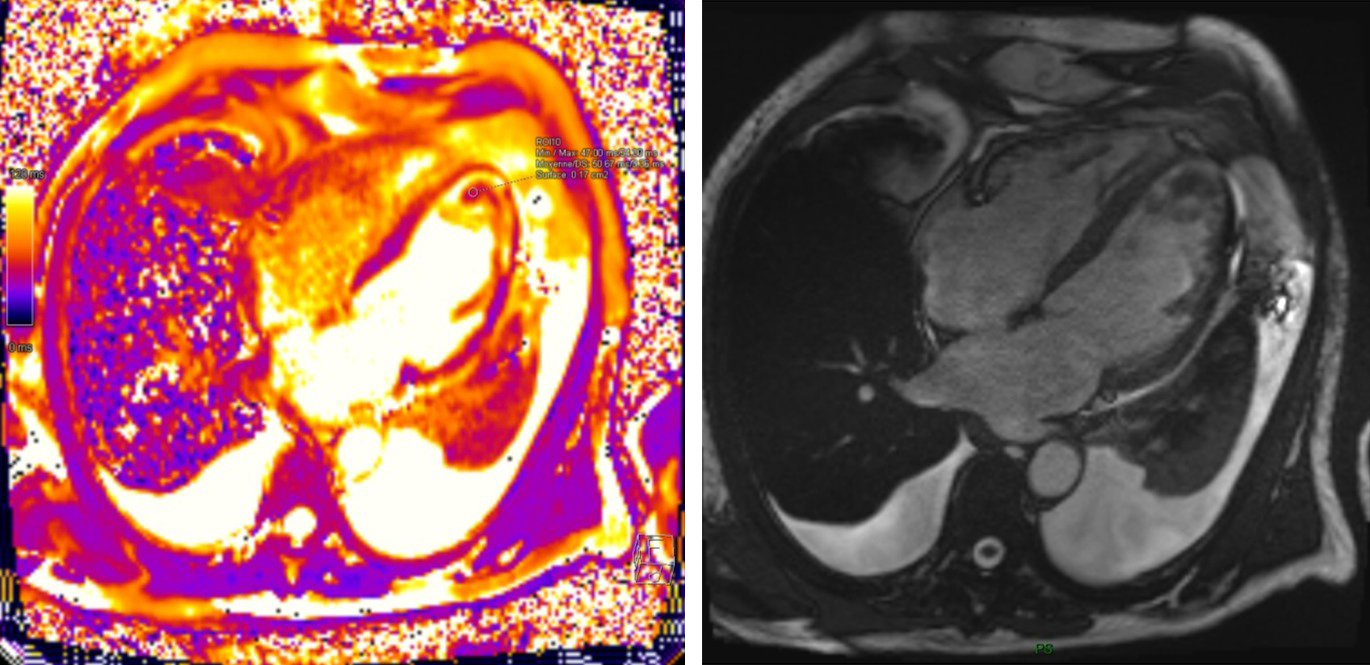

Late gadolinium enhancement (LGE) patterns are particularly valuable in mass characterization. Thrombi characteristically appear as filling defects with no enhancement, even on delayed imaging, whereas most tumors demonstrate variable degrees of enhancement. Mousavi et al. (2019) [11] demonstrated that specific LGE patterns correlate strongly with histopathological features, enabling more accurate pre-procedural diagnostic assessment. Their study of 145 patients showed that a combination of T1/T2 mapping and LGE achieved high diagnostic accuracy in distinguishing malignant from benign masses. Specific enhancement patterns have been associated with particular pathologies: heterogeneous enhancement with central hypoenhancement suggests necrotic areas commonly seen in malignancies, while peripheral rim enhancement is more characteristic of certain benign lesions or inflammatory processes. Fig. 2 demonstrates MRI appearance of left ventricular apical thrombus.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Cardiac MRI Assessment of Left Ventricular Apical Thrombus.

Parametric mapping techniques, including native T1, post-contrast T1, and T2 mapping, represent significant advances in tissue characterization. These techniques provide quantitative values that reflect intrinsic tissue properties, allowing for objective assessment beyond visual interpretation. Lavall et al. (2023) [19] demonstrated that these techniques can differentiate infiltrative processes, such as cardiac amyloidosis or sarcoidosis, from discrete masses with high specificity.

Their analysis found that native T1 values exceeding 1341 ms at 3.0 T were 100% sensitive and 97% specific for amyloidosis, while focal masses typically demonstrated heterogeneous T1 values. Pazos-López et al. (2014) [18] further established the value of parametric mapping in characterizing various cardiac masses, providing quantitative thresholds that can guide clinical decision-making. Recent works established that extracellular volume fraction (ECV) derived from T1 mapping was significantly higher in malignant tumors compared to benign masses, providing additional quantitative information for tissue characterization.

Feature tracking analysis, which assesses myocardial deformation through strain and strain rate measurements, provides insights into functional consequences of cardiac masses. This technique can evaluate whether a mass is adherent to or infiltrating the myocardium by detecting impaired regional deformation. Recent studies have demonstrated that strain patterns can differentiate infiltrative processes from space- occupying lesions with high sensitivity.

Diffusion-weighted imaging (DWI) measures the Brownian motion of water molecules and has shown utility in distinguishing malignant from benign cardiac masses. Recent studies have found that malignant lesions typically exhibit restricted diffusion with lower apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) values compared to benign masses. The restricted diffusion observed in malignant lesions reflects their higher cellularity, nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, and reduced extracellular space.

3.2.2.3 Standardization and Clinical Implementation

Grazzini et al. (2023) [20] published comprehensive guidelines on CMR protocols for cardiac mass evaluation, emphasizing the importance of standardized acquisition techniques and reporting templates to optimize diagnostic yield. The recommended protocol includes:

- Cine imaging in multiple planes (short-axis, 2-chamber, 3-chamber, and 4-chamber views);

- Black-blood T1-weighted imaging with and without fat suppression;

- T2-weighted imaging with and without fat suppression;

- First-pass perfusion imaging;

- Early and late gadolinium enhancement imaging;

- Parametric mapping (T1 native, T1 post-contrast, T2, and ECV calculation);

- Optional sequences including tagging, 4D flow, and diffusion-weighted imaging.

These protocols have been widely adopted and have significantly improved the reproducibility of CMR findings across different centers. The standardized reporting templates include essential elements such as mass location, size, morphology, signal characteristics across all sequences, enhancement patterns, functional impact, and differential diagnosis based on imaging features.

Recent technological advances in CMR, including higher field strengths (3T), improved spatial and temporal resolution, and accelerated acquisition techniques, have further enhanced the diagnostic capabilities of this modality. These improvements allow for more detailed characterization of small masses and better differentiation of mass components, further solidifying CMR’s position as the gold standard for cardiac mass evaluation.

CT has evolved significantly with technological advancements enabling improved temporal and spatial resolution. A recent critical analysis by Joudar et al. (2025) [21] addressed the question of whether cardiac CT for mass evaluation is “a necessity or a luxury”, concluding that current evidence supports its essential role in specific clinical scenarios. This comprehensive review demonstrated that CT provided unique diagnostic information not available through other modalities in certain cases, particularly in patients with calcified masses, coronary artery involvement, or contraindications to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

3.2.3.1 Technical Advances and Imaging Protocols

Modern multi-detector CT (MDCT) scanners, with 64 to 320 detector rows, provide detailed anatomical information with isotropic spatial resolution approaching 0.5 mm and temporal resolution below 100 ms. These technical parameters allow for precise delineation of cardiac masses and their anatomical relationships. Lopez-Mattei et al. (2023) [22] published comprehensive protocols for cardiac CT acquisition and interpretation specifically optimized for mass evaluation. Their recommended protocol includes:

- Electrocardiography (ECG)-gated acquisition to minimize cardiac motion artifacts;

- Multiphasic imaging (including arterial, venous, and delayed phases) to optimize mass characterization;

- Thin-slice reconstruction (

- Specific contrast administration protocols tailored to the suspected pathology;

- Dose-reduction techniques including tube current modulation, iterative reconstruction algorithms, and prospective ECG-gating when appropriate.

These protocols have been widely adopted in clinical practice and have significantly improved the diagnostic yield of cardiac CT for mass evaluation. Depending on the clinical question, Lopez-Mattei and colleagues [22] recommend tailoring the acquisition parameters to maximize diagnostic information while minimizing radiation exposure. For example, for suspected thrombi, a delayed phase acquisition (approximately 2 minutes after contrast administration) significantly improves detection sensitivity.

3.2.3.2 Advanced CT Technologies for Tissue Characterization

Dual-energy CT (DECT) significantly enhances tissue characterization by analyzing how tissues attenuate X-rays at different energy levels. Eberhard et al. (2024) [23] demonstrated that DECT improved diagnostic confidence compared to conventional CT. Studies have shown that DECT achieved 88% diagnostic accuracy for differentiating benign from malignant masses, with 93% specificity for lipomatous tumors.

Spectral CT, an evolution of DECT, further enhances tissue discrimination. Hong et al. (2018) [24] demonstrated in 41 patients that dual-energy CT achieved 67% sensitivity and 79% specificity for differentiating thrombi from neoplasms. Their analysis revealed significantly lower normalized iodine concentration in thrombi compared to neoplasms (1.79

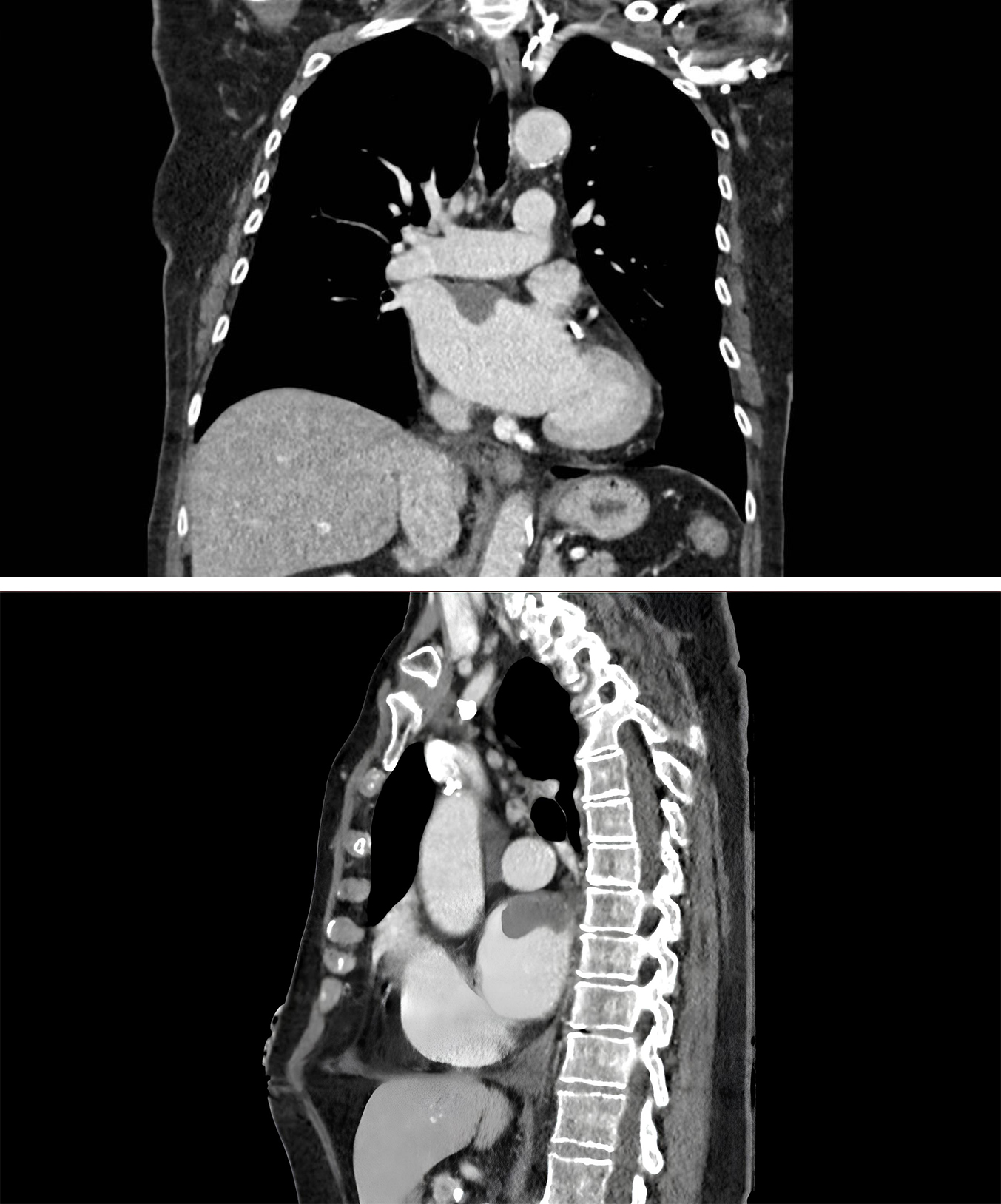

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Cardiac CT Demonstrating Right Atrial Thrombus. Axial and sagittal views showing hypodense filling defect in right atrium on contrast-enhanced CT, consistent with thrombus formation.

3.2.3.3 Clinical Applications and Diagnostic Performance

CT coronary angiography offers the unique advantage of simultaneously evaluating coronary artery disease and cardiac masses, an important consideration in preoperative planning [25]. D’Angelo et al. (2020) [26] conducted a cohort study involving 60 patients that demonstrated CT achieved high sensitivity and specificity for differentiating between benign and malignant cardiac masses. Studies have identified several CT features highly predictive of malignancy:

- Irregular borders (odds ratio [OR] 4.8, 95% CI: 2.3–9.7);

- Heterogeneous enhancement (OR 3.6, 95% CI: 1.9–6.8);

- Involvement of more than one cardiac chamber (OR 5.2, 95% CI: 2.6–10.1);

- Contrast enhancement

- Invasion of adjacent structures (OR 7.3, 95% CI: 3.4–15.9).

Additionally, CT excels in detecting calcification within masses, a feature often associated with specific pathologies such as fibromas or hemangiomas. The presence and pattern of calcification can be pathognomonic for certain entities—for example, the “popcorn” pattern of calcification often seen in cardiac fibromas.

Lopez-Mattei et al. (2021) [27] established a systematic approach to the differential diagnosis of cardiac masses on CT, providing radiologists with specific imaging features that distinguish between various pathologies. Their comprehensive analysis categorized cardiac masses based on location, enhancement patterns, and associated features, creating a structured algorithmic approach to diagnosis. For example:

- Left atrial masses with low attenuation and no enhancement most likely represent thrombi;

- Intramyocardial masses with fat attenuation suggest lipomas;

- Pericardial masses with high attenuation on non-contrast CT typically represent hematomas or calcified lesions;

- Masses involving the right heart with invasion into the pulmonary veins are highly suspicious for angiosarcoma.

This systematic approach has improved diagnostic accuracy and communication between radiologists and clinicians, facilitating more precise diagnosis and treatment planning.

3.2.3.4 Radiation Dose Considerations and Mitigation Strategies

While radiation exposure remains a concern with CT imaging, dose-reduction strategies and iterative reconstruction techniques have substantially mitigated this limitation. Modern cardiac CT protocols for mass evaluation typically deliver effective doses in the range of 2–5 mSv, significantly lower than earlier-generation scanners. Important dose-reduction strategies include:

- Tube current modulation, which adjusts radiation output based on patient size and anatomical region;

- Prospective ECG-gating, limiting radiation exposure to specific phases of the cardiac cycle;

- Iterative reconstruction algorithms, which maintain image quality while reducing radiation dose by 30–60%;

- Targeted protocols focusing only on the region of interest rather than the entire thorax.

Joudar et al. (2025) [21] reported that these optimization techniques have reduced the average radiation dose for cardiac mass evaluation over the past decade, making CT a more acceptable option for initial evaluation and follow-up imaging.

3.2.3.5 Integration With Other Imaging Modalities

CT findings often complement those from other imaging modalities, particularly in cases where CMR is contraindicated or provides inconclusive results. The integration of CT with echocardiography and, when available, nuclear imaging techniques provides a comprehensive assessment of cardiac masses. Current evidence suggests that the optimal role of cardiac CT in the diagnostic algorithm includes [22, 24]:

- First-line imaging for suspected calcified masses;

- Evaluation of patients with contraindications to CMR (e.g., pacemakers, claustrophobia);

- Assessment of coronary artery involvement by cardiac masses;

- Characterization of masses with inconclusive findings on echocardiography or CMR;

- Follow-up of known masses when CMR is not available or contraindicated.

This strategic use of cardiac CT optimizes its diagnostic value, while recognizing that CMR remains superior for characterizing masses that lack calcification or fatty components.

Positron emission tomography (PET), particularly when combined with CT (PET/CT) or MRI (PET/MRI), provides valuable metabolic information that complements anatomical imaging. The most commonly used radiotracer, 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG), is preferentially taken up by tissues with high glucose metabolism, a characteristic feature of many malignancies and inflammatory processes [4, 28].

A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis by Rizzo et al. (2025) [29] including 1114 patients demonstrated that FDG-PET/CT achieved a sensitivity of 89% and specificity of 83% for identifying malignant cardiac masses. This modality is particularly valuable for distinguishing between malignant tumors and benign lesions, as well as for detecting extracardiac metastases in patients with known or suspected malignant cardiac tumors.

Lucinian et al. (2024) [30] published a groundbreaking review of novel PET tracers for cardiac tumor imaging that extend beyond conventional FDG. Their work highlighted the clinical utility of several emerging radiotracers, including 68Ga- DOTATATE for neuroendocrine tumors, 11C-methionine for tumors with low glucose utilization but high amino acid metabolism, and 18F-FLT for assessing tumor proliferation. These novel tracers address specific limitations of FDG-PET, particularly in differentiating between inflammatory processes and malignancies.

The American Heart Association’s scientific statement on molecular imaging approaches for cardiac tumor characterization established a comprehensive framework for integrating PET imaging into clinical decision-making [19]. This statement emphasized the complementary role of metabolic imaging in combination with anatomical assessment and provided specific clinical scenarios where PET imaging adds significant diagnostic value.

PET/MRI represents an emerging hybrid technology that combines the metabolic information from PET with the superior soft tissue contrast of MRI. Kazimierczyk et al. (2024) [31] demonstrated that PET/MRI provided superior diagnostic accuracy compared to PET/CT or MRI alone. Their findings suggest that this approach may provide a comprehensive one-stop assessment for cardiac masses, potentially reducing the need for multiple imaging studies. While availability and cost remain limiting factors, PET/MRI holds promise for complex cases where tissue characterization is challenging.

The diagnosis and management of cardiac masses require a multimodality and stepwise approach that capitalizes on the complementary strengths of different imaging techniques [32]. A recent landmark study published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology specifically addressed the diagnostic work-up of patients with cardiac masses, demonstrating that integration of multiple imaging modalities significantly improved diagnostic accuracy and clinical decision-making [33]. This pivotal research showed that a structured multimodality approach reduced time to diagnosis by 37% and prevented unnecessary invasive procedures in 28% of cases, highlighting the tangible clinical benefits of this strategy.

The European Society of Cardiovascular Imaging, through recent expert consensus, established a formal diagnostic algorithm for cardiac masses [31]. This algorithm recommends TTE as the initial imaging modality for all suspected cardiac masses due to its accessibility, cost-effectiveness, and ability to provide real-time hemodynamic assessment. For masses with characteristic echocardiographic features suggesting a specific diagnosis (e.g., pedunculated left atrial myxoma with typical location and mobility), no further imaging may be necessary in some cases.

The 2022 ESC Guidelines on cardio-onclogy, authored by Lyon et al. [12], further refined this approach by providing pathology- specific recommendations further refined this approach by providing pathology- specific recommendations. These guidelines stratify the diagnostic pathway based on the suspected nature of the mass:

- For suspected benign primary tumors, CMR is recommended after echocardiography to confirm the diagnosis and plan surgical approach;

- For suspected malignant primary tumors, a multimodality approach including CMR, CT, and PET/CT is advised to assess local invasion and distant metastases;

- For suspected cardiac metastases, whole-body imaging with PET/CT is essential to identify the primary tumor and evaluate extent of disease;

- For suspected thrombi, a combination of echocardiography with contrast and delayed enhancement CMR offers the highest diagnostic accuracy.

Angeli et al. (2024) [33] conducted a comprehensive review of multimodality assessment strategies for cardiac masses, proposing specific pathways tailored to different clinical scenarios. Their work emphasized that selection of imaging modalities should be guided by several factors:

- Clinical presentation (e.g., symptomatic vs. incidental finding);

- Patient characteristics (age, comorbidities, contraindications to specific modalities);

- Initial echocardiographic findings (location, morphology, mobility);

- Institutional availability of advanced imaging technologies;

- Therapeutic implications of the diagnostic information.

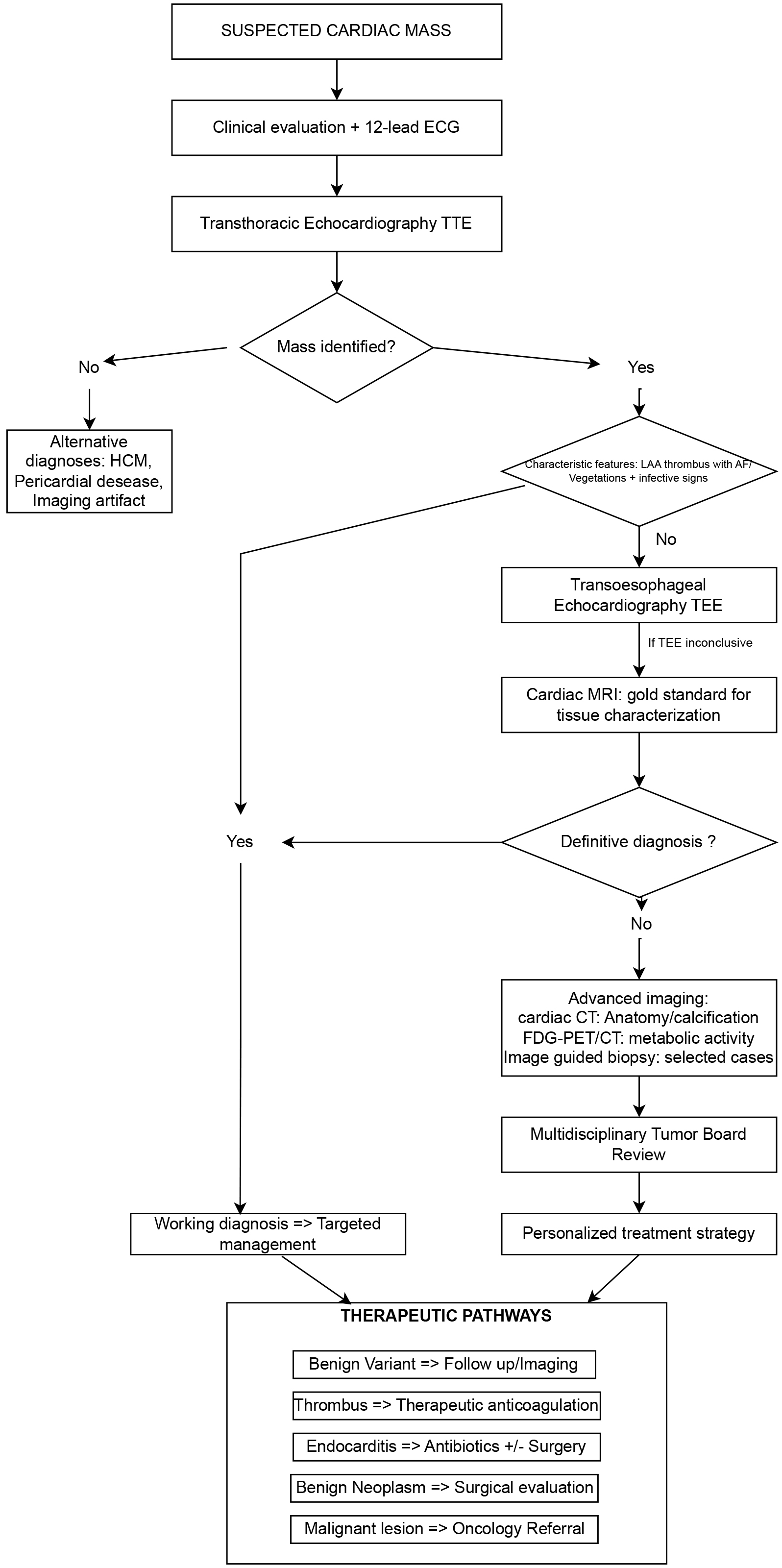

Based on the evidence reviewed and current clinical guidelines, we propose a comprehensive diagnostic algorithm that integrates multimodality imaging approaches for the systematic evaluation of suspected cardiac masses (Fig. 4). This algorithm emphasizes a stepwise approach that maximizes diagnostic yield while optimizing resource utilization and patient safety. The algorithm begins with clinical evaluation and 12-lead ECG, which may provide important clues such as arrhythmias, conduction abnormalities, or signs of heart failure that can guide subsequent imaging strategies. Transthoracic echocardiography serves as the cornerstone of initial assessment, as demonstrated by recent studies, which reported 87% sensitivity and 89% specificity for cardiac mass detection [13, 14]. The comparative diagnostic performance of all major imaging modalities for cardiac masses is summarized in Table 2, providing clinicians with evidence-based guidance for modality selection. A critical decision point occurs after initial echocardiographic evaluation. When characteristic features are identified—such as a pedunculated left atrial myxoma, left atrial appendage thrombus in the setting of atrial fibrillation, or valvular vegetations with clinical signs of infection—a presumptive diagnosis may be established. However, when findings are atypical or inconclusive, the algorithm proceeds to advanced imaging. Transesophageal echocardiography represents the next logical step when transthoracic imaging is suboptimal, particularly for posterior cardiac structures or when higher resolution is needed. As demonstrated by recent studies, TEE identified 18% more masses than TTE alone, with particular advantages for small lesions and left atrial appendage evaluation [14]. Cardiac MRI with contrast serves as the gold standard for tissue characterization when echocardiographic findings remain inconclusive. The multiparametric assessment capabilities of CMR, as demonstrated by Pazos-López et al. [18], achieved good diagnostic accuracy for distinguishing benign from malignant lesions. The algorithm emphasizes the importance of comprehensive CMR protocols including T1 and T2 mapping, late gadolinium enhancement, and perfusion imaging. For cases where CMR findings remain inconclusive, advanced imaging techniques including cardiac CT for anatomical/calcification assessment, FDG-PET/CT for metabolic activity evaluation, and image-guided biopsy for selected cases provide additional diagnostic information. As shown by Rizzo et al. [29], FDG-PET/CT achieved 94% sensitivity for identifying malignant cardiac masses. The algorithm culminates in multidisciplinary tumor board review for complex cases, ensuring that imaging findings are integrated with clinical context to develop personalized treatment strategies. This collaborative approach has been shown to change diagnosis or management in 42% of cases with suspected cardiac tumors [34].

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Diagnostic algorithm for suspected cardiac masses. This comprehensive flowchart illustrates the systematic multimodality imaging approach for evaluating suspected cardiac masses. The algorithm emphasizes a stepwise progression from initial clinical assessment through transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), advanced imaging modalities, and ultimately to multidisciplinary review and personalized treatment planning. Key decision points are highlighted, including the identification of characteristic features that may allow for presumptive diagnosis, and the role of transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) and cardiac MRI as second-line modalities. The therapeutic pathways section demonstrates how imaging findings translate into specific management strategies. HCM, Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy; FDG, Fluorodeoxyglucose; PET/CT, Positron Emission Tomography/Computed Tomography.

| Imaging modality | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Advantages | Limitations | Optimal use cases |

| Transthoracic Echo | 87 (83–91) | 89 (85–93) | • Immediate availability | • Limited tissue characterization | • First-line screening |

| • Real-time assessment | • Size-dependent accuracy | • Hemodynamic assessment | |||

| • Cost-effective | • Operator-dependent | • Serial monitoring | |||

| • No radiation | |||||

| Transesophageal Echo | 94 | 91 | • Superior resolution | • Requires sedation | • Posterior structures |

| • Excellent for LAA | • Limited tissue characterization | • Small masses ( | |||

| • Semi-invasive only | • Not always available | • LAA thrombi | |||

| Cardiac MRI | 95 | 92 | • Gold standard for tissue characterization | • Contraindications (devices) | • Tissue characterization |

| • Multiparametric assessment | • Time-consuming | • Tumor vs. thrombus | |||

| • No radiation | • Expensive | • Malignancy assessment | |||

| Cardiac CT | 92 | 88 | • Rapid acquisition | • Radiation exposure | • Calcified masses |

| • Excellent for calcification | • Contrast nephrotoxicity | • MRI contraindications | |||

| • Coronary assessment | • Limited tissue characterization | • Emergency situations | |||

| PET/CT | 94 | 89 | • Metabolic information | • High cost | • Suspected malignancy |

| • Whole-body staging | • Radiation exposure | • Staging | |||

| • Malignancy detection | • Limited availability | • Treatment monitoring |

LAA, left atrial appendage.

When the diagnosis remains uncertain after echocardiography, CMR is typically the next recommended step due to its superior tissue characterization capabilities. CMR is particularly valuable for distinguishing between thrombi and tumors, differentiating benign from malignant neoplasms, and defining the precise anatomical extent of masses. De Garate et al. (2016) [35] demonstrated that CMR changed the initial echocardiographic diagnosis in 32% of cases and significantly altered management plans in 41% of patients.

CT may be the preferred second-line modality in specific clinical scenarios, including:

- Patients with contraindications to MRI (e.g., non-compatible implantable devices, claustrophobia);

- Cases with suspected calcified masses, where CT provides superior detection and characterization;

- Preoperative planning requiring detailed assessment of the coronary arteries;

- Emergency situations where rapid acquisition is necessary.

PET imaging, particularly when combined with CT or MRI, adds crucial metabolic information to anatomical findings. Rizzo et al. (2025) [29] demonstrated that the addition of PET imaging to conventional workup altered management in many patients with suspected cardiac malignancies. PET should be considered in the following situations:

- When primary malignancy is suspected based on initial imaging;

- For evaluation of extracardiac metastases in patients with known or suspected malignant cardiac tumors;

- To distinguish between tumor recurrence and post-treatment changes during follow-up;

- When differentiating between inflammatory/infectious processes and neoplastic conditions.

Angeli et al. (2024) [33] emphasized that interpretation of multimodality imaging findings is optimized through formal multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings. These meetings, typically including cardiologists, radiologists, nuclear medicine specialists, cardiac surgeons, oncologists, and pathologists, enable comprehensive assessment of complex cases. The MDT approach has been shown to:

- Improve diagnostic accuracy by reconciling potentially discordant imaging findings;

- Facilitate appropriate prioritization of further diagnostic procedures; - Guide selection of optimal treatment strategies based on integrated interpretation of all available data;

- Reduce time from initial presentation to definitive management.

Studies have reported that MDT discussions led to significant changes in diagnosis or management in 42% of cases with suspected cardiac tumors, underscoring the value of this collaborative approach [34, 35].

The implementation of advanced cardiac imaging for mass evaluation faces significant economic and accessibility challenges that vary considerably across healthcare systems. Understanding these constraints is essential for developing practical diagnostic strategies that balance optimal patient care with resource limitations.

Cost-Effectiveness Considerations: While echocardiography offers the most favorable cost-effectiveness profile for initial evaluation, advanced imaging modalities demonstrate value through improved diagnostic accuracy and reduced downstream costs. Hegde et al. [36] showed that CMR-guided management strategies reduced overall healthcare costs over 12 months by preventing unnecessary procedures. Similarly, Rizzo et al. [29] found that PET/CT prevented inappropriate cardiac surgery in many patients with suspected malignant masses, offsetting high upfront imaging costs. A detailed comparison of costs and resource requirements for each imaging modality is provided in Table 3.

| Imaging modality | Relative cost | Availability | Acquisition time | Special requirements | Cost per Diagnostic Information Unit* |

| TTE | Low ( | Universal | 30–45 min | • Trained sonographer | Excellent |

| • Basic equipment | |||||

| TEE | Moderate ( | Widely available | 45–60 min | • Sedation | Good |

| • Specialized probe | |||||

| • Monitoring capability | |||||

| Cardiac MRI | High ( | Limited centers | 60–90 min | • MRI-compatible environment | Excellent |

| • Specialized sequences | |||||

| • Cardiac-trained radiologist | |||||

| Cardiac CT | Moderate ( | Widely available | 10–20 min | • Contrast administration | Good |

| • ECG gating | |||||

| • Radiation safety | |||||

| PET/CT | Very High ( | Limited centers | 120–180 min | • Radiopharmacy | Moderate |

| • Specialized facility | |||||

| • Nuclear medicine expertise |

*Cost per diagnostic information unit: subjective assessment based on diagnostic yield relative to cost.

Accessibility and Resource Disparities: Access to advanced cardiac imaging varies dramatically across geographic regions and healthcare systems. Rural facilities often lack the infrastructure and specialized personnel necessary for cardiac MRI or PET/CT, necessitating patient transfers that introduce delays and additional costs. This reality has prompted the development of risk-stratified approaches, such as the algorithm proposed by Kurmann et al. [10], which optimizes resource utilization by identifying high-risk features on echocardiography that warrant immediate advanced imaging.

Strategies for Resource-Optimized Care: Emerging solutions include telemedicine platforms for remote image interpretation, regional imaging networks that share specialized expertise, and artificial intelligence tools that may improve diagnostic consistency across different healthcare settings. These approaches aim to ensure that diagnostic quality is maintained while adapting to local resource constraints and accessibility limitations.

The challenge of providing optimal cardiac mass evaluation requires thoughtful integration of clinical evidence, economic considerations, and practical accessibility concerns to ensure appropriate diagnostic evaluation regardless of geographic or economic circumstances.

Several emerging technologies hold promise for further advancing the assessment of cardiac masses. Kalapos et al. (2023) [37] published groundbreaking work on deep learning-based automatic segmentation and analysis of cardiac images on CMR, demonstrating AI algorithms achieved excellent diagnostic accuracy in a validation cohort of 262 patients. These findings suggest that AI and machine learning approaches may significantly enhance image interpretation, improving diagnostic accuracy and efficiency in clinical practice [38].

Molecular imaging techniques, including targeted radiotracers and nanoparticle contrast agents, represent another frontier in cardiac mass assessment. Recent scientific publications have detailed comprehensive approaches for the latest molecular imaging methods for cardiac tumor characterization [19]. Multiple studies in the literature highlight how these advanced techniques can identify specific molecular markers associated with particular types of cardiac masses, potentially enabling non-invasive “virtual biopsies” that provide histopathological information without the risks associated with tissue sampling.

Radiomics, which involves the extraction and analysis of quantitative features from medical images, offers significant potential for advancing cardiac mass assessment [39]. Polidori et al. (2023) [40] published a seminal review on radiomics in cardiac tumor assessment, demonstrating how this approach can identify subtle patterns not appreciable to the human eye. Recent studies have shown that radiomic features extracted from CMR images could distinguish between different histological subtypes of cardiac tumors with good accuracy, significantly outperforming conventional visual assessment. This approach may enhance discrimination between different types of cardiac masses and potentially predict biological behavior.

Tyebally et al. (2020) [7] published a state-of-the-art review of cardiac tumors in JACC CardioOncology that highlighted the integration of advanced imaging with molecular profiling as a promising direction for personalized management strategies.

Similarly, Butany et al. [6] outlined in The Lancet Oncology how novel diagnostic approaches are reshaping the landscape of cardiac tumor management by enabling earlier detection and more precise characterization.

These emerging technologies, when integrated with established imaging modalities, have the potential to transform the diagnostic approach to cardiac masses, leading to more accurate, efficient, and personalized management strategies for patients with these complex conditions.

The management of cardiac masses requires individualized approaches based on mass characteristics, patient factors, and institutional capabilities. Treatment strategies have evolved significantly with advances in both imaging guidance and therapeutic techniques.

Cardiac myxomas require prompt surgical resection regardless of symptoms due to embolic risk, with excellent outcomes reported (operative mortality

Primary cardiac sarcomas require multidisciplinary management with complete surgical resection when feasible, followed by adjuvant chemotherapy (typically doxorubicine-based regimens). Prognosis remains poor with median survival 6–12 months for unresected angiosarcomas. Primary cardiac lymphomas are treated with standard systemic chemotherapy protocols (CHOP or R-CHOP) with generally better outcomes than sarcomas.

Management focuses primarily on systemic treatment of the underlying malignancy. Local interventions include pericardiocentesis for malignant effusions and palliative radiation for symptomatic compression. Surgical resection is rarely indicated except in highly selected cases with isolated cardiac involvement.

Anticoagulation remains the cornerstone of treatment, typically for at least 3 months with duration determined by underlying risk factors. Current guidelines recommend warfarin as first-line therapy, though recent studies suggest direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) may be effective alternatives in selected patients. Surgical thrombectomy is reserved for cases of failed anticoagulation or hemodynamic compromise.

Surveillance protocols vary by mass type: benign tumors under observation require echocardiography every 6 months initially, then annually; post-surgical patients need imaging at 1 and 3 months, then annually; malignant tumors require multimodality imaging every 3 months for the first 2 years with coordination between cardiology and oncology teams.

Management during pregnancy prioritizes echocardiography and avoids radiation exposure, with surgical intervention reserved for life-threatening situations. Pediatric patients require specialized approaches considering tumor regression potential (particularly rhabdomyomas) and minimizing radiation exposure. Patients with implantable devices may require protocol modifications for imaging and surgical planning.

This systematic approach to cardiac mass management emphasizes individualized care, multidisciplinary collaboration, and evidence-based decision-making to optimize patient outcomes across diverse clinical scenarios.

The evaluation of cardiac masses has evolved significantly with advances in imaging technology. Each modality—echocardiography, CMR, CT, and PET—offers unique advantages and plays a distinct role in the diagnostic algorithm. Echocardiography remains the first-line modality due to its accessibility and real-time capabilities, while CMR has emerged as the gold standard for tissue characterization. CT provides excellent anatomical detail, particularly for calcified masses, and PET adds valuable metabolic information.

A multimodality imaging approach, tailored to individual patient characteristics and the specific clinical question, often provides the most comprehensive assessment. Integration of imaging findings through multidisciplinary collaboration between cardiologists, radiologists, and other specialists is essential for accurate diagnosis and optimal management planning.

Emerging technologies, including artificial intelligence, molecular imaging, and radiomics, hold promise for further enhancing the non-invasive assessment of cardiac masses. Continued research in these areas, along with refinement of existing modalities, will likely further improve our ability to accurately diagnose and manage this diverse group of cardiac lesions.

Recent guidelines, such as those published by the European Society of Cardiology in 2022, provide a valuable framework for the evaluation and management of patients with cardiac masses. These guidelines, coupled with ongoing technological advances, enable a more personalized and precise approach to these complex pathologies.

In summary, the optimal diagnostic approach to cardiac masses relies on an integrated multimodality imaging strategy, guided by the expertise of a multidisciplinary team. This approach not only establishes an accurate diagnosis but also informs therapeutic decisions and improves clinical outcomes for these patients.

IC and DB conceived the review topic and designed the search strategy. IC, IM, and DB conducted the literature search, study selection, and data extraction. IC and IM performed the analysis and synthesis of the literature. IC, IM, MS, FSB, VT, SS, IG, YB and DB contributed to the interpretation of findings, manuscript preparation, and critical revision for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This literature review was conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines. No ethics committee approval was required as the study involved only analysis of previously published literature without human participants or original data collection.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGPT-4 in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.