1 Department of Cardiac Surgery, Harefield Hospital, UB9 6JH London, UK

Abstract

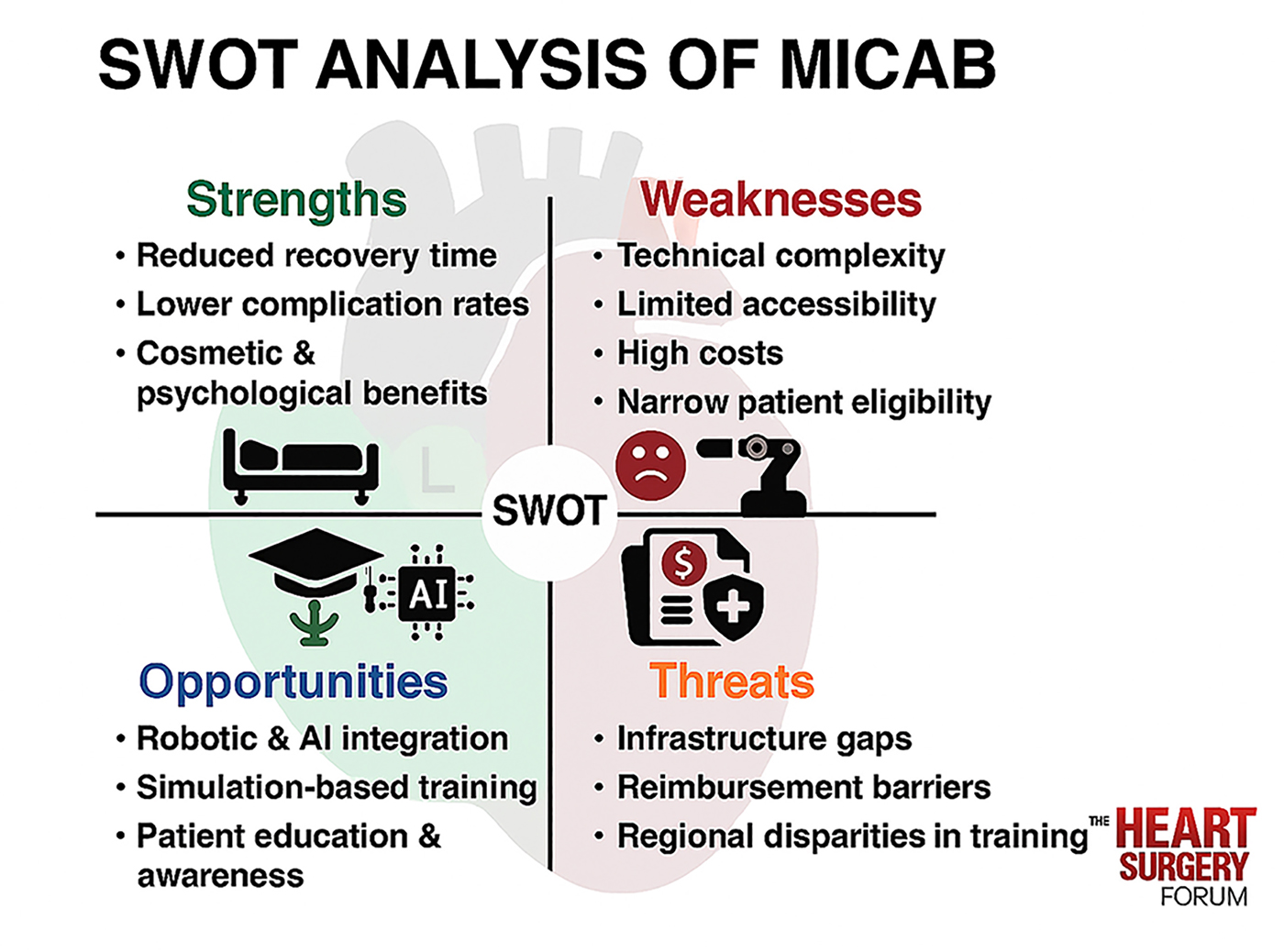

Minimally invasive coronary artery bypass surgery (MICAB) has emerged as a promising alternative to conventional coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), offering reduced recovery time, lower surgical morbidity, and improved postoperative cosmetic outcomes. As the landscape of cardiovascular surgery continues to evolve, MICAB provides an opportunity to enhance patient care through refined techniques that minimize surgical invasiveness. However, despite the advantages of MICAB, this procedure faces several challenges, including technical complexity, limited accessibility, high costs, and restrictions in patient selection. This narrative review aims to conduct a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis of MICAB to assess the current impact and prospects of this procedure. By systematically evaluating the advantages and limitations of MICAB, this review identifies areas for improvement, technological advancements, and strategic initiatives to optimize clinical outcomes. Key findings suggest that MICAB significantly enhances postoperative recovery and reduces complication rates compared to traditional CABG, although economic barriers and surgeon training requirements hinder the broader implementation of MICAB. Future research and policy developments must address these challenges to expand the application of MICAB while ensuring accessibility and cost-effectiveness in diverse healthcare settings.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- coronary artery bypass grafting

- minimally invasive surgical procedures

- cardiac surgical procedures

- robotic surgical procedures

- postoperative complications

Coronary artery disease (CAD) remains one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide, necessitating effective revascularization strategies to improve patient outcomes. Coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) has long been the gold standard for surgical intervention in cases of severe CAD, demonstrating superior long-term survival compared to percutaneous coronary interventions (PCI) in select patient populations [1]. Traditional CABG, performed via median sternotomy, enables comprehensive revascularization but is associated with significant morbidity, prolonged recovery time, and a higher risk of complications [2].

In response to these challenges, minimally invasive coronary artery bypass surgery (MICAB) has emerged as an innovative approach that offers patients a less invasive alternative while maintaining the effectiveness of conventional CABG. MICAB techniques [3], including minimally invasive direct coronary artery bypass grafting (MIDCAB) and totally endoscopic coronary artery bypass grafting (TECAB), utilize smaller incisions, reduce surgical trauma, and improve postoperative recovery [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22] (Table 1, Ref. [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22]). The integration of robotic-assisted techniques and hybrid revascularization strategies has further expanded the scope of minimally invasive approaches, enabling enhanced precision and patient-centered surgical interventions [23].

| Author | Year | Country | Study design | No. of patients | Key outcomes |

| Mohr et al. [4] | 2001 | Germany | Retrospective | 27 | TECAB completed in 22 of 27 cases with 95.4% patency at 3 months’ follow-up |

| Dogan et al. [5] | 2002 | Germany | Retrospective | 62 | Conversion rate to any kind of incision was 25% with no mortalities, 3 patients required reexploration via a median sternotomy, and one patient suffered a hypoxemic brain damage |

| Mishra et al. [6] | 2006 | India | Retrospective | 13 | No conversion with 1 patient having 50% anastomotic narrowing resulting in coronary angioplasty |

| Argenziano et al. [7] | 2006 | United States, Austria | RCT | 85 | Five (6%) conversions to open techniques with no deaths or strokes, one early reintervention, one myocardial infarction (1.5%), occlusions in 6 patients at 3 months, and 91% overall freedom from reintervention or angiographic failure |

| de Cannière et al. [8] | 2007 | Belgium, Germany | Retrospective | 228 | Conversion rate of 28% with 97% angiographic patency or lack of ischemic signs on stress electrocardiography, and 5% incidence MACE within 6 months |

| Kappert et al. [9] | 2008 | Germany | Retrospective | 41 | Hospital survival of 100%, overall survival of 92.7% (38/41 patients), freedom from reintervention of the LAD of 87.2% after a mean of 69 |

| Srivastava et al. [10] | 2010 | United States | Retrospective | 214 | No myocardial infarction, operative mortality, or conversion with TIMI 3 flow in all grafts except one and 1.4% reintervention rate |

| Balkhy et al. [11] | 2011 | United States | Retrospective | 120 | 1 death, 1 stroke, 1 myocardial infarction, 3 conversions, with 94.1% graft patency at 4 months |

| Jegaden et al. [12] | 2011 | France | Retrospective | 59 | No conversion, one hospital cardiac death (1.7%), 8.5% reoperation for bleeding, 10% LAD reintervention at 3 months, 85 |

| Srivastava et al. [13] | 2012 | United States | Retrospective | 164 | No conversion with 1 in-hospital mortality and 99.5% graft patency |

| Dhawan et al. [14] | 2012 | United States | Retrospective | 106 | Conversion rate of 6.6%, 7.5% renal failure rate, and at least 21.7% 1 major morbidity/mortality (4 deaths) |

| Wiedemann et al. [15] | 2013 | United States, Austria | Retrospective | 500 | Similar in-hospital mortality of men (0.8%) and women (1.5%), as well as long-term-survival rates and freedom from MACCE at 1, 3, and 5 years |

| Efendiev et al. [16] | 2015 | Russia | Prospective | 50 | No conversion and no complications |

| Zaouter et al. [17] | 2015 | France | Retrospective | 38 | 100% TECAB with lower transfusion rate and shorter intensive care unit and hospital stay |

| Pasrija et al. [18] | 2018 | United States | Retrospective | 50 | Operative mortality of 2% with significantly higher operative and total hospital costs |

| Cheng et al. [19] | 2021 | China | Retrospective | 126 | No conversion, operative mortality, or adverse events |

| Balkhy et al. [20] | 2022 | United States | Retrospective | 544 | 1 conversion, 0.9% mortality, 97% early graft patency, with 2.7%, cardiac mortality and 92.5% freedom from MACE at mid-term follow-up of 38 months |

| Claessens et al. [21] | 2022 | Belgium | Retrospective | 244 | 30-day mortality of 1.94% with 11.65% MACCE and long-term mortality |

| Claessens et al. [22] | 2024 | Belgium | Retrospective | 1500 | 30-day mortality of 1.73% with 94.7% 1-year survival and 91.7% 1-year MACCE-free survival |

LAD, left anterior descending; MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; RCT, randomized controlled trial; TECAB, totally endoscopic coronary artery bypass.

Despite its growing adoption, MICAB faces numerous challenges related to surgeon training, procedural complexity, and cost-effectiveness. Its applicability remains limited by technical demands, accessibility issues, and patient selection criteria, restricting widespread clinical implementation [24]. To better understand the advantages, limitations, and future potential of MICAB, a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats) analysis provides a structured framework for evaluating its role in modern cardiac surgery. This review aims to systematically assess MICAB using SWOT analysis, offering critical insights into its clinical value, strategic opportunities for advancement, and potential threats that may hinder its broader adoption.

MICAB has gained recognition for its ability to reduce surgical trauma while maintaining clinical efficacy comparable to conventional CABG. As cardiac surgery continues to evolve, MICAB offers a promising alternative, characterized by accelerated recovery, lower complication rates, improved cosmetic outcomes, and enhanced postoperative quality of life.

One of the most widely acknowledged advantages of MICAB is its ability to significantly shorten recovery times compared to traditional CABG. The procedure eliminates the need for a full sternotomy, reducing trauma to the chest wall and allowing patients to return to normal activities sooner. Studies indicate that MICAB patients experience shorter hospital stays, with many discharged within three to five days postoperatively, compared to seven to ten days for conventional CABG patients [25]. Additionally, MICAB patients demonstrate a reduced dependence on intensive care and require fewer postoperative interventions, contributing to lower hospital resource utilization and healthcare costs [26].

Early mobilization is a crucial factor in preventing complications such as deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary infections following cardiac surgery. MICAB facilitates faster ambulation due to reduced postoperative pain and less reliance on opioid analgesics. Patients undergoing MICAB have reported greater ease in resuming physical activities, including walking and light exercise, within the first few weeks post-surgery [27]. Enhanced recovery protocols tailored for MICAB further optimize rehabilitation, allowing patients to regain functional capacity more rapidly than those who undergo conventional CABG [28].

MICAB significantly decreases the risk of complications associated with traditional CABG, particularly infections, excessive bleeding, and postoperative arrhythmias. Conventional CABG requires opening the chest through a sternotomy, which increases the risk of deep sternal wound infections. MICAB, on the other hand, utilizes smaller incisions that expose patients to fewer external contaminants, thereby minimizing the likelihood of wound-related complications [29, 30, 31]. Furthermore, MICAB procedures can be performed off-pump, eliminating the need for cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), which has been linked to systemic inflammatory responses and cognitive dysfunction in some patients [32, 33].

The avoidance of CPB also reduces transfusion requirements, improving overall hemodynamic stability during surgery. Studies have reported lower rates of atrial fibrillation—a common postoperative complication following CABG—among patients undergoing MICAB, likely due to reduced systemic inflammation and improved myocardial preservation [34]. These findings suggest that MICAB not only offers equivalent revascularization outcomes but also lowers the risk of complications that negatively impact long-term recovery and patient satisfaction [35].

Traditional CABG leaves patients with a long midline scar, which can be a source

of psychological distress, particularly in younger individuals and those

concerned with aesthetic outcomes. MICAB eliminates the need for a sternotomy,

instead using smaller incisions either under the ribs or in conjunction with

robotic-assisted technology, leading to less noticeable scarring and improved

cosmetic outcomes [25]. Although cosmetic benefit is often inferred from incision

size and surgical access, emerging patient-centered evidence supports this claim.

A randomized prospective study comparing patient body image, self-esteem, and

scar satisfaction following robot-assisted versus conventional cardiac

surgery reported significantly better

scores across body image (p = 0.026), self-esteem (p = 0.038),

and scar assessment scales (p

Beyond cosmetic benefits, smaller incisions result in less wound discomfort and a faster healing process. The reduced surgical trauma decreases postoperative inflammation, allowing patients to experience less pain and minimal restriction in upper body movement. Studies evaluating patient-reported outcomes have noted that individuals undergoing MICAB express greater comfort and mobility when compared to those recovering from traditional CABG, further reinforcing the psychological and functional advantages of minimally invasive approaches [29].

Short-term [37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62] (Table 2, Ref. [37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62]) and long-term [63, 64, 65, 66, 67] (Table 3, Ref. [63, 64, 65, 66, 67]) clinical studies have demonstrated improved patient outcomes with MICAB compared to traditional sternotomy-based CABG. These studies also report that MICAB provides comparable graft patency rates to conventional CABG, particularly when using the left internal mammary artery (LIMA) for left anterior descending (LAD) artery revascularization [13, 20]. The durability of grafts remains a critical factor in determining success rates, and MICAB has proven effective in maintaining functional grafts over extended follow-up periods. Additionally, MICAB patients often report higher postoperative quality of life due to decreased pain and fewer post-surgical complications [36].

| Author | Year | Study design | Country | No. of patients | Surgical approach | Use of CPB | Key outcomes |

| Wu et al. [37] | 1997 | Prospective | Taiwan | 42 | Left minithoracotomy | Yes | Mean 3.8 grafts/patient with uneventful postoperative course for all patients |

| Yeh et al. [38] | 1998 | Retrospective | Taiwan | 25 | Left minithoracotomy | Yes | Complete revascularization for all patients (3 to 4 grafts) with uneventful postoperative course |

| Groh et al. [39] | 1999 | Retrospective | United States | 229 | Left minithoracotomy | Yes | Early results were similar to those of conventional CABG |

| Dogan et al. [40] | 2002 | RCT | Germany | 19 | Left minithoracotomy | Yes | Equivalent myocardial and cerebral protection and similar whole-body inflammatory response to conventional CABG |

| Srivastava et al. [41] | 2003 | Retrospective | United States | 200 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Mean 2.9 |

| Singh et al. [42] | 2004 | Retrospective | India | 27 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Mean 3.2 grafts/patient with no operative mortalities, conversion to CPB or sternotomy |

| Bhaskar and Sharma [43] | 2007 | Prospective | New Zealand | 27 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Mean 2.30 grafts/patient with no operative mortalities, conversion to CPB or sternotomy |

| McGinn et al. [44] | 2009 | Retrospective | USA & Canada | 450 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Mean 2.1 |

| Rogers et al. [45] | 2013 | RCT | United Kingdom, Italy | 91 | Left minithoracotomy | No | ThoraCAB resulted in fewer grafts with no overall clinical benefit relative to OPCAB with 10% higher average total cost |

| Rabindranauth et al. [46] | 2014 | Retrospective | United States | 130 | Left minithoracotomy | Yes | MICS CABG resulted in fewer grafts per patient with similar early outcomes to OPCAB |

| Ziankou and Ostrovsky [47] | 2015 | Retrospective | Belarus | 212 | Left minithoracotomy | No | MVST CABG as safe as OPCAB and ONCAB and associated with less wound infections, perioperative blood loss, shorter hospital length of stay and time to return to full physical activity |

| Andrawes et al. [48] | 2018 | Retrospective | United States | 200, 500 | Left minithoracotomy | No | As experience increased the number of bypassed vessels increased and the operative time and conversion to sternotomy decreased |

| Nambiar et al. [49] | 2018 | Retrospective | India | 819 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Multivessel TAG using composite BITA Y conduit possible with excellent outcomes |

| Diab et al. [50] | 2019 | Retrospective | Germany | 21 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Multivessel TAG using BITA possible with good postoperative and short term outcomes |

| Guida et al. [51] | 2020 | Retrospective | Venezuela | 2528 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Multivessel OPCAB with average of 2.8 |

| Snegirev et al. [52] | 2020 | Retrospective | Russia | 245 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Complete revascularization with average of 2.6 |

| Babliak et al. [53] | 2020 | Retrospective | Ukraine | 229 | Left minithoracotomy | Yes | Same number of grafts with 0 mortality, MI and conversion to sternotomy |

| Davierwala et al. [54] | 2021 | Retrospective | Germany | 88 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Multivessel BITA grafting with mean 2.4 |

| Rajput et al. [55] | 2021 | Retrospective | India | 100 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Mean 2.33 |

| Zhang et al. [56] | 2021 | Retrospective | China | 186 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Mean 2.81 grafts/patient with 99.5% complete revascularization and overall graft patency rate of 96.3% |

| Tachibana et al. [57] | 2022 | Retrospective | Japan | 247 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Mean 2.6 |

| Yang et al. [58] | 2022 | Retrospective | China | 97 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Mean 1.9 |

| Çaynak and Sicim [59] | 2022 | Retrospective | Turkey | 184 | Left minithoracotomy | Yes | Mean 3.3 |

| Solanki et al. [60] | 2023 | Retrospective | India | 50 | Left minithoracotomy | No | Mean 2.53 |

| Kyaruzi et al. [61] | 2023 | Retrospective | Turkey | 100 | Left minithoracotomy | Yes | Mean 3.1 |

| Sellin et al. [62] | 2023 | Retrospective | Germany | 102 | Left minithoracotomy | Yes | Mean 3.2 |

AF, atrial fibrillation; BITA, bilateral internal thoracic artery grafting; CABG, coronary artery bypass grafting; CPB, cardiopulmonary bypass; MI, myocardial infarction; MICS CABG, minimally invasive coronary artery bypass grafting; MVST, multivessel small thoracotomy; ONCAB, on-pump coronary artery bypass; OPCAB, off-pump coronary artery bypass; TAG, total arterial grafting.

| Author | Year | Country | Study design | No. of patients | Follow-up duration | Key outcomes |

| Verevkin et al. [63] | 2024 | Germany | Retrospective | 186 | Mean 5 years | Survival of 93.3% |

| Rufa et al. [64] | 2025 | Germany | Retrospective | 597 | Mean 7.8 |

Actuarial survival rates for one, three, five, eight, and ten years were 99%, 95%, 91%, 85%, and 80%, respectively |

| Guo et al. [65] | 2024 | Canada | Retrospective | 566 | Mean 7.0 |

Survival of 82.2% |

| Liang et al. [66] | 2022 | China | Retrospective | 281 | Mean 2.68 years | 2.8% rates of 2- or 4-year cardiac death |

| PSM | 172 | |||||

| Barsoum et al. [67] | 2015 | United States | Retrospective | 61 | Mean 3.7 |

5-year all-cause mortality of 19.7% |

MACCE, major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events; PSM, propensity score matching.

Furthermore, MICAB has shown favorable outcomes among high-risk populations, including elderly patients and those with multiple comorbidities. By reducing the physiological stress associated with surgery, MICAB minimizes adverse postoperative events and allows for safer surgical intervention in patients who may not tolerate traditional CABG well [68]. These findings reinforce MICAB as an essential option for selective patient populations, ensuring effective revascularization with reduced surgical risks.

Despite the numerous advantages of MICAB, several limitations hinder its widespread adoption. These weaknesses primarily stem from technical complexity, accessibility challenges, financial constraints, and patient selection criteria, limiting its applicability in broader clinical settings.

One of the primary drawbacks of MICAB is its technical complexity, which presents a steep learning curve for surgeons. Unlike conventional CABG, which provides a full view of the surgical field through median sternotomy, MICAB requires operating through small incisions or robotic-assisted access, restricting direct visualization and maneuverability [69]. Surgeons must rely on specialized instrumentation and endoscopic or robotic techniques, which demand extensive training and experience to achieve proficiency [70].

Additionally, MICAB requires precise anastomotic techniques under restricted access, increasing the risk of technical errors in less experienced hands. Studies indicate that surgical learning curves for MICAB often exceed those of conventional CABG, with higher initial procedural times and greater dependency on specialized assistance during early cases [71]. As a result, proficiency in MICAB takes longer to attain, and case volumes remain lower compared to traditional CABG in many institutions. This limitation affects surgical consistency and overall success rates in centers with limited exposure to MICAB procedures [70].

MICAB remains inaccessible to many patients and hospitals due to the need for specialized equipment, infrastructure, and trained personnel. Unlike conventional CABG, which can be performed in nearly all cardiothoracic surgical centers, MICAB requires robotic platforms, thoracoscopic tools, and dedicated hybrid operating rooms, making its implementation more resource-intensive [26]. Smaller hospitals and facilities with budget constraints may lack the necessary infrastructure to offer MICAB, limiting patient access to this procedure.

Furthermore, access to surgeons trained in MICAB techniques remains a significant barrier to its adoption. A global survey of cardiothoracic surgeons revealed insufficient exposure and training opportunities as major obstacles to expanding MICAB practices [72]. Given the requirement for specialized robotic and endoscopic training, not all cardiac surgeons receive adequate preparation to perform MICAB, affecting its availability and regional disparities in access [73].

The financial burden associated with MICAB is another critical limitation. The initial investment in robotic-assisted platforms, specialized instruments, and training programs significantly increases the cost of implementing MICAB at surgical centers [74]. Compared to conventional CABG, which utilizes standard operating rooms and widely available instruments, MICAB requires dedicated technological investments, making it financially restrictive for many institutions.

Moreover, longer procedural times during the learning phase contribute to increased operating room expenses, including anesthesia duration, consumables, and surgical personnel costs. Insurance coverage for MICAB procedures varies widely, with reimbursement models often favoring traditional CABG, further restricting financial feasibility for hospitals adopting minimally invasive approaches [26]. While MICAB has the potential for cost savings in terms of shorter hospital stays and fewer postoperative complications, high upfront costs remain a significant barrier to widespread implementation.

Not all patients are eligible for MICAB, as certain anatomical and clinical factors limit its applicability. Multivessel disease, calcified coronary arteries, and complex comorbid conditions pose challenges for MICAB procedures, often necessitating traditional CABG for complete and durable revascularization [24]. Patients with poor pulmonary function or advanced thoracic deformities may also be unsuitable candidates due to restricted surgical access in a minimally invasive setting [3].

Additionally, MICAB is generally preferred for isolated LAD bypasses, whereas patients with extensive coronary disease requiring multiple grafts often undergo conventional CABG to ensure comprehensive revascularization [24]. The selection criteria for MICAB continue to evolve with advancements in robotic and hybrid techniques, but current limitations restrict its availability to select patient populations, limiting its role as a universal alternative to conventional CABG [25].

As MICAB continues to evolve, several opportunities exist to improve accessibility, refine surgical techniques, and enhance clinical outcomes. Advancements in technology, increased surgeon training programs, and a growing awareness of MICAB’s benefits contribute to its potential expansion in cardiovascular surgery.

The continuous development of surgical technology presents a significant opportunity for the refinement and broader adoption of MICAB. Innovations such as robotic-assisted surgery, enhanced imaging techniques, and improved instrumentation have significantly improved precision and procedural outcomes. The integration of artificial intelligence in surgical planning has also contributed to better preoperative assessments, leading to optimized graft placement and reduced intraoperative complications [75].

Robotic-assisted MICAB allows for greater dexterity, improved visualization, and reduced manual fatigue, enabling surgeons to perform intricate anastomoses with superior accuracy. Studies indicate that robotic-assisted coronary revascularization results in fewer technical errors and shorter operating times as surgeons gain proficiency [76]. Additionally, endoscopic and three-dimensional imaging technologies have improved anatomical visualization, allowing for more precise dissection and graft placement, leading to enhanced surgical success rates [24]. The continuous refinement of these technologies presents an opportunity to standardize MICAB techniques, making them more accessible to surgical teams worldwide.

Expanding structured training programs and fellowships for MICAB presents an opportunity to increase surgeon competency and procedural adoption rates. Traditional CABG techniques are widely taught during cardiothoracic surgical training, but MICAB requires specific expertise in minimally invasive approaches, including thoracoscopic and robotic techniques. Currently, the availability of MICAB-focused fellowships is limited, restricting exposure for cardiac surgeons who seek to specialize in minimally invasive coronary revascularization [26].

Standardizing simulation-based learning, mentorship programs, and international surgical workshops would help address training gaps, ensuring that more surgeons develop the technical skills required for MICAB. Studies suggest that structured mentorship programs significantly shorten the MICAB learning curve, improving success rates and reducing complication risks associated with early procedural attempts [26]. Increasing access to such programs would accelerate the widespread adoption of MICAB and improve its overall clinical outcomes.

Greater awareness among patients, healthcare providers, and policymakers presents an opportunity to expand the utilization of MICAB. Many patients remain unfamiliar with minimally invasive options, often assuming that traditional CABG is the only effective approach for coronary revascularization. Increasing patient education efforts through hospital-based information sessions and online resources can help individuals make informed decisions regarding their surgical options [77]. Table 4 summarizes strategic modalities for patient education tailored to MICAB candidates.

| Educational strategy | Purpose | Description | Practical implementation |

| Individualized Education Plans | Match learning style and cognitive needs | Tailors information delivery based on visual, auditory, or kinesthetic preferences | Clinician-guided orientation sessions using varied handouts and analogies |

| Use of Visual Aids & Multimedia | Improve retention and procedural clarity | Utilizes dynamic visuals to convey anatomy, procedure, and recovery expectations | 3D animations, touchscreen modules, and surgical walkthroughs |

| Plain Language Communication | Enhance health literacy and reduce misinterpretation | Replaces jargon with accessible phrasing and culturally sensitive language | Leaflets written at Grade 6–8 literacy level; verbal counseling with simplified terminology |

| Shared Decision-Making Tools | Foster collaborative treatment choices | Empowers patients to weigh risks, benefits, and preferences | Structured decision aids; risk calculators embedded in clinic workflows |

| Digital Engagement Platforms | Extend education beyond clinical setting | Leverages technology for reinforcement, reminders, and feedback loops | Secure patient apps; SMS-based recovery tips; portals with personalized educational timelines |

3D, three dimensional; SMS, short message service; MICAB, minimally invasive coronary artery bypass surgery.

Clinicians and primary care providers play a critical role in referring patients to cardiothoracic surgical centers that specialize in MICAB. Raising awareness among healthcare professionals regarding MICAB’s benefits, patient eligibility criteria, and long-term outcomes would facilitate more appropriate referrals. Additionally, healthcare policymakers can develop reimbursement models and funding initiatives to support hospitals in acquiring robotic platforms and expanding MICAB programs, making the procedure more accessible to a broader patient population [75].

Ongoing research efforts present an opportunity to refine MICAB techniques, optimize patient selection criteria, and expand its clinical indications. Future studies evaluating long-term graft patency, multivessel revascularization strategies, and hybrid surgical approaches will further establish MICAB’s efficacy as an alternative to conventional CABG [56].

Clinical trials focusing on robotic-assisted multi-arterial grafting, enhanced intraoperative imaging techniques, and personalized artificial intelligence-driven surgical planning have the potential to improve procedural outcomes and expand MICAB’s role in complex coronary disease management. Additionally, economic studies analyzing the cost-effectiveness of MICAB relative to traditional CABG could provide valuable data for healthcare decision-makers, ensuring that funding structures support the implementation of minimally invasive approaches [78].

Despite its advantages, MICAB faces several threats that may hinder its broader adoption and sustainability in clinical practice. These challenges include competition from alternative treatments, regulatory barriers, financial constraints, and patient skepticism, all of which must be addressed to ensure MICAB’s long-term viability.

The rise of PCI as an alternative to surgical revascularization presents a significant challenge to MICAB’s adoption. Advances in PCI techniques, including drug-eluting stents and improved catheter-based interventions, have expanded the eligibility criteria for nonsurgical revascularization, reducing the number of patients requiring coronary bypass surgery [79]. Many patients with single-vessel or moderate multivessel disease opt for PCI due to its minimally invasive nature and shorter recovery time, creating competition for MICAB within the same patient demographic [80].

Hybrid coronary revascularization, which combines PCI with MICAB, has also gained traction, allowing surgeons to selectively perform bypass surgery on critical coronary arteries while utilizing stenting for less complex lesions [81]. While this approach enhances individualized patient care, it also reduces the number of patients requiring full MICAB procedures, further challenging its widespread implementation. As these alternative techniques continue to evolve, MICAB must demonstrate superior long-term efficacy and improved patient benefits to remain competitive in the field of coronary revascularization.

The implementation of MICAB is subject to stringent regulatory approval processes, which can delay widespread clinical adoption. Many regions require extensive validation of new surgical techniques and technologies before granting approval for routine clinical use [82]. Robotic-assisted MICAB, in particular, faces prolonged certification requirements due to its dependence on specialized equipment and the need for formalized surgeon training programs [74].

In addition to regulatory barriers, hospitals must comply with safety protocols and quality assurance standards, which can restrict access to MICAB procedures. Concerns regarding intraoperative risks, procedural consistency, and long-term outcomes may contribute to conservative decision-making among hospital administrators and surgical boards [74]. Without streamlined regulatory pathways, the integration of MICAB into routine surgical practice remains slow, limiting its accessibility for a wider patient population.

The cost implications of MICAB pose a significant threat to its widespread adoption. While MICAB offers potential long-term cost savings by reducing postoperative complications and shortening hospital stays, the initial financial investment required to establish MICAB programs remains high [26]. Hospitals must allocate substantial resources to acquire robotic platforms, specialized surgical instruments, and dedicated training programs, creating financial barriers for institutions with limited budgets [74].

Reimbursement models further complicate MICAB’s accessibility. Many healthcare systems prioritize reimbursement for conventional CABG and PCI, leaving MICAB with lower financial incentives for providers and hospitals. Without favorable insurance coverage and funding models, MICAB programs may struggle to achieve financial sustainability, slowing their expansion across healthcare institutions [29]. In evaluating the cost-effectiveness of MICAB techniques, it is essential to balance short-term expenditures with long-term outcome benefits. Robotic-assisted approaches, while associated with higher initial costs, have demonstrated potential reductions in postoperative complications, ICU length of stay, and overall recovery time. These downstream efficiencies may offset upfront investment, particularly in high-volume centers with streamlined protocols. Pasrija et al. [18] compared robotic coronary surgery to conventional sternotomy-based procedures and found that despite elevated intraoperative costs, robotic techniques were associated with shorter hospital stays and comparable clinical outcomes, suggesting favorable economic utility in appropriately selected patients.

Addressing economic barriers requires advocacy for updated reimbursement structures and cost-effectiveness studies that highlight MICAB’s long-term benefits.

Patient skepticism regarding MICAB poses another challenge to its widespread acceptance. Despite its advantages, many individuals are hesitant to undergo minimally invasive procedures due to concerns about safety, efficacy, and unfamiliarity with robotic-assisted techniques [74]. Patients often associate CABG with traditional sternotomy-based surgery and may require extensive counseling before opting for MICAB.

Additionally, reports of early-stage technical challenges and variable surgeon expertise may contribute to doubts regarding MICAB’s reliability. While high-volume centers with experienced surgeons report favorable outcomes, newer institutions may struggle with initial learning curve complications, leading to inconsistent patient experiences [74]. Overcoming patient perception challenges requires targeted educational initiatives, improved surgeon training programs, and transparent discussions on procedural risks and benefits.

MICAB presents a complex balance of advantages, limitations, future opportunities, and external challenges. A SWOT analysis provides a structured approach to understanding how MICAB fits within modern cardiac surgery and how its strengths can be leveraged while mitigating its weaknesses and addressing external barriers.

MICAB offers substantial benefits, including reduced recovery time, lower complication rates, improved cosmetic outcomes, and enhanced patient satisfaction. These strengths provide a compelling case for adopting MICAB as an alternative to traditional CABG, particularly in selective patient populations. However, the procedure faces inherent technical challenges, requiring specialized training and surgical expertise. The steep learning curve and limited availability of trained surgeons restrict the widespread adoption of MICAB, particularly in lower-resource healthcare environments [74].

Another area where strengths and weaknesses intersect is accessibility. While MICAB reduces hospital stays and leads to fewer postoperative complications, its implementation remains financially demanding. The need for robotic-assisted platforms, thoracoscopic tools, and dedicated surgical teams increases operational costs, limiting its availability across different healthcare institutions [24]. Bridging this gap requires an investment in technology, structured surgeon training programs, and policy-level adjustments to ensure MICAB becomes a financially viable option for hospitals and patients.

Although this review utilizes a structured SWOT framework, it is important to acknowledge that such methodology relies predominantly on expert consensus and synthesized literature, rather than direct patient-level data. While multicenter studies with early and long-term outcomes have been summarized (Tables 1,2,3), future research should incorporate patient-reported experiences and real-world registry data to complement strategic analysis. Greater insight into functional recovery, quality of life, and graft durability from longitudinal cohorts will strengthen clinical decision-making and inform broader MICAB adoption.

Integrating MICAB more broadly into surgical practice requires addressing both systemic and procedural barriers. Expanding training programs and fellowship opportunities can increase surgeon proficiency and reduce technical inconsistencies across institutions. Standardized training models, including simulation-based learning and mentorship initiatives, have shown promise in improving MICAB outcomes and facilitating procedural confidence among newly trained surgeons [74].

From a healthcare policy standpoint, reimbursement models must evolve to accommodate MICAB procedures. Many current funding structures prioritize conventional CABG and PCI, leaving MICAB in a financially vulnerable position. Updated reimbursement policies that account for MICAB’s potential long-term benefits—such as reduced postoperative complications and shorter hospital stays—could drive broader adoption and encourage institutions to invest in minimally invasive approaches [74].

Expanding patient awareness is another key strategy for improving MICAB’s adoption rate. Many patients remain uninformed about minimally invasive cardiac surgery options, and targeted education programs led by physicians and healthcare organizations can enhance public understanding. Highlighting MICAB’s cosmetic benefits, faster recovery, and comparable long-term outcomes to traditional CABG can help address patient skepticism and increase demand for minimally invasive revascularization [74].

Table 5 provides a structured summary of MICAB’s core strengths, procedural limitations, and persisting evidence gaps—highlighting both the factors driving its clinical uptake and the areas requiring further empirical substantiation, such as long-term multivessel data, standardized patient-reported outcomes, and cross-institutional reproducibility.

| Domain | Strengths | Limitations | Evidence gaps |

| Patient Recovery & Morbidity | - Reduced postoperative pain | - Not universally applicable in high-risk or obese patients | - Limited data on recovery profiles in multivessel or redo surgeries |

| - Shorter hospital stay | |||

| - Lower wound complications | |||

| Cosmesis & Patient Acceptance | - Smaller incisions | - Variable access and exposure challenges in certain anatomies | - Longitudinal patient-reported outcomes (PROMs) lacking |

| - Improved cosmetic outcomes | |||

| - Higher patient satisfaction | |||

| Technical & Procedural Aspects | - Avoids full sternotomy | - Steep learning curve | - Sparse data on cross-institution reproducibility and procedural standardization |

| - Compatible with robotic assistance | - Requires specialized training and infrastructure | ||

| - Preserves chest wall integrity | |||

| Clinical Outcomes | - Comparable short-term outcomes to conventional CABG in selected populations | - Less robust evidence in multivessel CAD and complex anatomies | - Limited long-term data beyond 5 years |

| Health Economics | - Potential reduction in total cost through faster recovery and fewer complications | - Upfront costs of robotic platforms and training | - Formal cost-effectiveness analyses across diverse healthcare systems needed |

| - Variable institutional feasibility |

CAD, coronary artery disease.

Further research is necessary to refine MICAB techniques, optimize patient selection criteria, and enhance procedural efficacy. Long-term studies evaluating graft patency in MICAB versus traditional CABG will provide insight into whether minimally invasive approaches maintain comparable durability. Additionally, research into hybrid revascularization strategies—combining MICAB with PCI—can help define how best to treat multivessel disease using a minimally invasive framework [81].

Technological advancements will play a critical role in MICAB’s future. Improving robotic-assisted precision, refining three-dimensional imaging techniques, and integrating artificial intelligence into surgical planning could enhance procedural outcomes and minimize technical challenges [74]. Further clinical trials focusing on these innovations would support evidence-based adoption of MICAB across more surgical centers.

Economic studies assessing MICAB’s cost-effectiveness compared to traditional CABG should also be prioritized. A deeper understanding of MICAB’s financial impact, particularly in high-volume cardiac centers, would help policymakers develop better funding models to support minimally invasive surgical programs. Addressing economic concerns through research-backed reimbursement proposals could lead to broader institutional investment in MICAB, ensuring sustainable implementation over the long term [83].

MICAB has emerged as a promising alternative to traditional CABG, offering significant advantages in terms of recovery time, reduced complications, cosmetic benefits, and improved patient satisfaction. Its technological advancements, including robotic-assisted techniques and enhanced imaging, have expanded its potential, making it an attractive option for coronary revascularization. Despite these strengths, MICAB faces notable limitations, including technical complexity, restricted accessibility, financial constraints, and patient selection criteria, which hinder its widespread adoption.

A SWOT analysis highlights the interplay between MICAB’s benefits and challenges, underscoring areas for improvement and strategic advancements. Addressing surgeon training gaps, streamlining regulatory approval processes, and advocating for more favorable reimbursement policies are essential to overcoming existing barriers. Additionally, expanding patient awareness and conducting further research into long-term graft durability and hybrid revascularization strategies will enhance MICAB’s clinical applicability.

Future efforts should focus on refining MICAB techniques, optimizing cost-effectiveness, and integrating artificial intelligence into surgical planning to improve precision and patient outcomes. By addressing current threats and leveraging emerging opportunities, MICAB can evolve into a more accessible and sustainable surgical approach. Continued innovation and policy adjustments will be crucial in ensuring its long-term viability, ultimately transforming coronary artery bypass surgery into a more patient-centric and efficient procedure.

SGR as the sole author drafted the manuscript, designed the research study, critically revised it for important intellectual content, read and approved the final manuscript. SGR participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The author declares no conflict of interest. Shahzad Gull Raja is serving as one of the Editorial Board members of this journal. We declare that Shahzad Gull Raja had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Guo-Wei He.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.