1 Department of Cardiology, Limassol General Hospital, 3304 Limassol, Cyprus

2 Department of Basic and Clinical Sciences, University of Nicosia Medical School, 2408 Nicosia, Cyprus

Abstract

Coronary artery crossing (CACr) constitutes a rare but clinically relevant anomaly of intrinsic coronary arterial anatomy. Current literature on this subject comprises isolated case reports and one case series. The purpose of this report is to present all cases of CaCr that have been reported in the English literature, highlighting its clinical implications.

We present the case of a patient with intermittent chest discomfort associated with psychological stress and evidence of crossing between the left anterior descending (LAD) artery and the first diagonal artery (DgA) on invasive coronary angiography. Myocardial bridging was also noted in the mid LAD artery but not at the crossing point or any other crossing artery segments, and produced obstructive (≥50%) dynamic lumen compromise. The patient was discharged in good condition and was prescribed aspirin, a statin, and diltiazem.

This review included 24 records that represented 27 patients, including the one presented in this report. The anomaly has been predominantly diagnosed in male patients and the diagnosis has predominantly been made using computed tomography coronary angiography. The most frequent CACr pattern revealed in 12 patients (44%) was a crossing between the LAD and left circumflex arteries while the second most frequent CACr pattern revealed in six patients (22%) was a crossing between the LAD artery and a DgA. There were five cases (19%) with evidence of an intramyocardial course, either at the point of vessel crossover or beyond that point. The crossing coronary arteries themselves were found to have atherosclerotic lesions in three patients (11%). Even though CaCr has not been associated with any clinical repercussions, cardiologists and cardiac surgeons should bear knowledge of this anomaly not only for diagnostic purposes when performing coronary artery angiograms but also in order to properly select and execute a revascularization procedure. Furthermore, CaCr may be associated with clinically relevant, functional coronary artery abnormalities such as spasm affecting the segments of the arteries crossing over each other or having an intramyocardial course. Unique patterns of coronary blood flow and wall shear stress may also be created at the crossover area, potentially increasing the risk of developing atherosclerosis.

Keywords

- angiography

- coronary anomalies

- computed tomography

- pathology

- intramyocardial artery

No crossing must exist between extramural arteries for a normal coronary arterial circulation [1]. Therefore, the existence of epicardial coronary arteries crossing each other en route to their dependent myocardial distributions, known as coronary artery crossing (CACr), is considered an anomaly in the intrinsic coronary artery anatomy [2]. CACr is considered benign because it has not been linked to specific clinical repercussions; however, CACr is a clinically relevant anomaly of which knowledge is valuable for both cardiologists and cardiac surgeons. This report presents a CACr case and an overview of all instances of this anomaly that have been reported in English literature, as far as we are aware. Our objective was to emphasize the clinical implications of CACr for diagnostic angiography and the selection and execution of revascularization procedures.

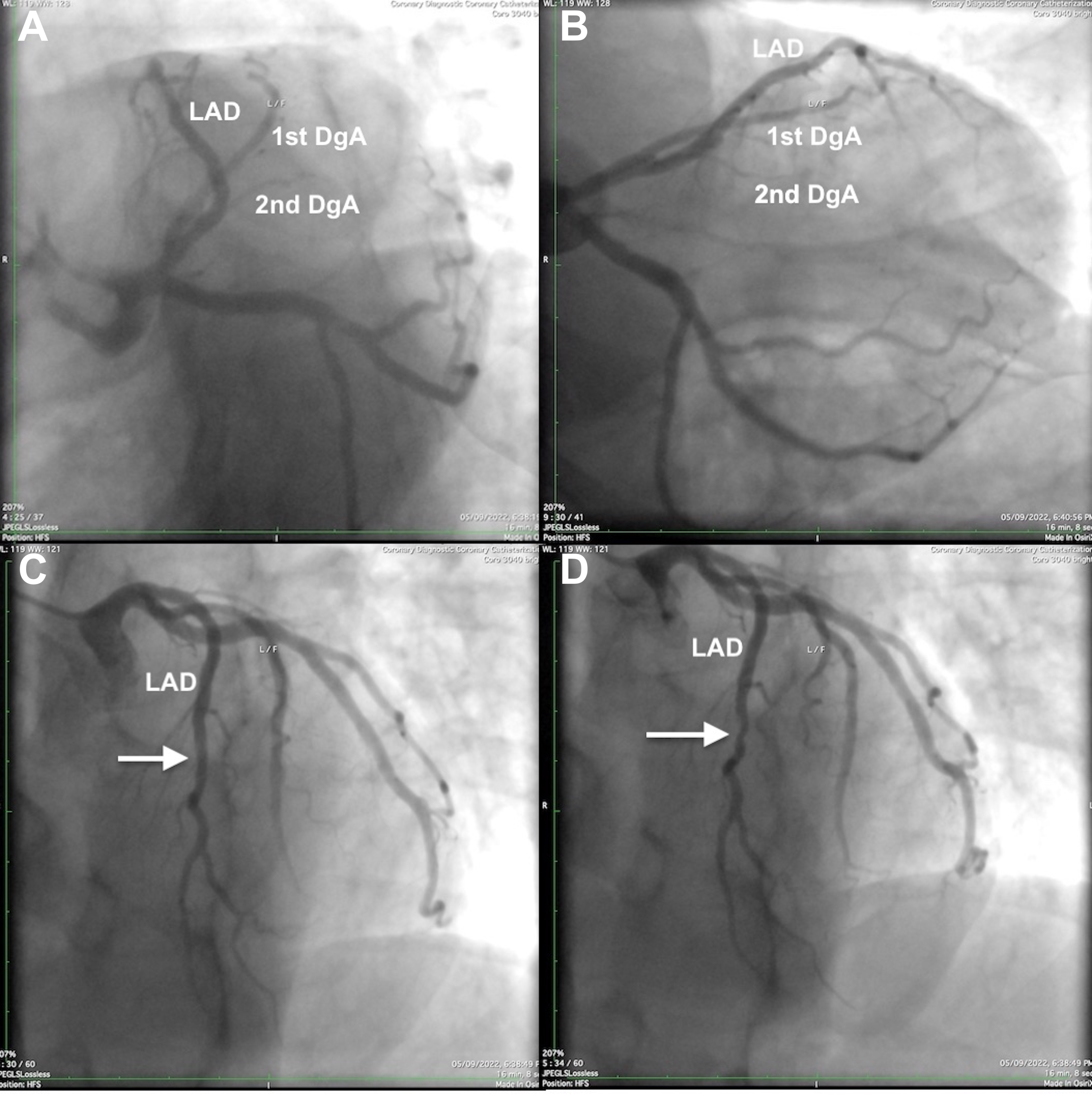

A 44-year-old man with a history of arterial hypertension and hyperlipidemia presented with intermittent chest discomfort associated with psychological stress. The patient showed no ischemic electrocardiographic (ECG) changes, no biochemical evidence of myocardial infarction, and his echocardiogram was essentially normal. However, the treadmill exercise–ECG test results were equivocal, prompting us to perform coronary angiography (CA). The latter showed patent coronary arteries and crossing between the left anterior descending (LAD) artery and the first diagonal artery (DgA) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Left coronary artery angiograms of the left anterior descending (LAD) artery and the first diagonal artery (1st DgA) crossing over each other. (A) Left anterior oblique–caudal view: the 1st DgA arises from the medial aspect of the ostial LAD artery and, after a short parallel course medial to the LAD artery, the 1st DgA crosses the LAD artery to arrive at the anterolateral left ventricular wall distal to the area supplied by a second gracile DgA (2nd DgA). (B) Right anterior oblique–caudal view. (C,D) Left anterior oblique–cranial projections (diastolic and systolic frames, respectively); note the mid LAD artery lumen compromise during systole (arrow), indicating myocardial bridging.

Specifically, the first DgA arose from the medial aspect of the ostial LAD artery and followed a short initial course medial to the LAD artery, before crossing the LAD artery to reach its dependent myocardial territory on the anterolateral aspect of the left ventricle distal to the area supplied by a second gracile DgA. Angiographic “milking” indicating myocardial bridging was noted in the mid LAD artery but not at the crossing point or any other crossing artery segments, and produced obstructive (

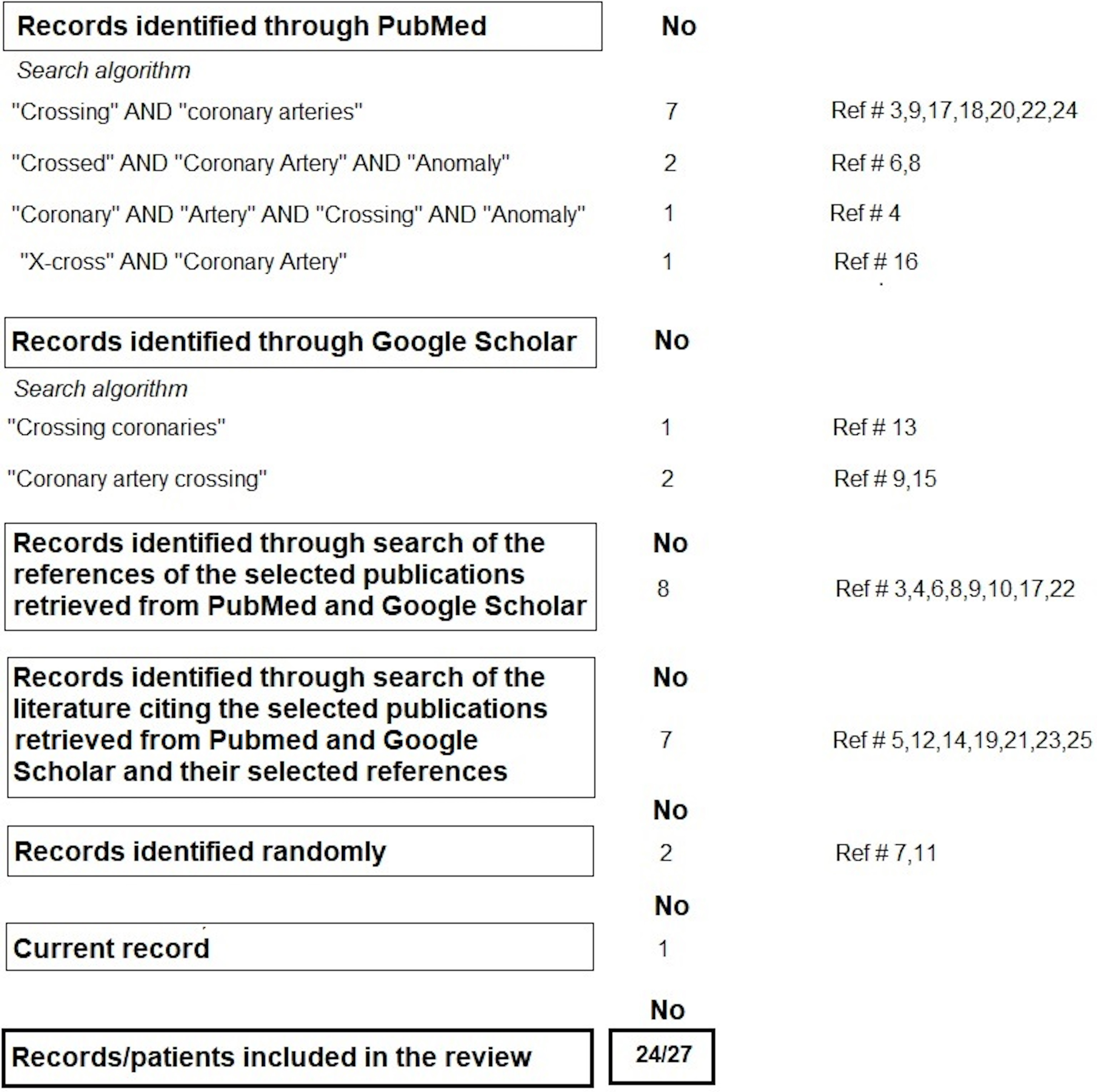

The crossing of two epicardial coronary arteries, which was first reported in 1985, is considered a benign anomaly [2, 3]. However, a subsequent report indicated that this anomaly may have clinical significance when planning revascularization procedures [4]. Furthermore, a recent case has shown that the depiction of CACr between the LAD and left circumflex (LCx) arteries through conventional coronary angiography can be challenging, thereby highlighting the diagnostic implications this anomaly may have [5]. Therefore, we conducted a literature review search of the PubMed and Google Scholar databases, which covered all published CACr cases from 1985 to 2024, using the search algorithms shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Literature search methodology.

All titles and abstracts found in the initial search were screened. Overall, we included all literature describing crossing between epicardial (extramural) coronary arteries/branches, whether having a normal or anomalous origin in patients with a structurally normal or abnormal heart. The references of the selected publications were also assessed for additional literature that was not detected in the initial search. Finally, the articles citing the selected publications detected in the initial search or their selected references were also assessed for additional literature. Ultimately, 24 records representing 27 patients, including the one presented in this report, were included in this review. The cases have been arranged in chronological order of publication and are shown in Table 1 (Ref. [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25]), along with their anatomical particularities.

| Authors, year of publication (Ref. #) | Number of patients; age (years); sex | Diagnostic modality | Crossing branches |

| * Particularities | |||

| Muyldermans et al. (1985) [3] | 4 | Conventional CA | RVB and AMB/RM and OMB/RCA and AMB/OMB and left PLVB |

| 52; female, and | * Confirmation of crossing during CABG surgery in one case | ||

| 52, 39, 52; males | * Obstructive ( | ||

| Bilazarian et al. (1991) [4] | 1 | Conventional CA | Second OMB (superior) and third OMB |

| 54; male | * Second OMB found to be Im after the crossing point during CABG (corkscrew distal pattern consistent with Im course) | ||

| * Third OMB found to be Im from the crossing point and beyond that during CABG | |||

| * High-grade stenosis in the second OMB proximal to the crossing point (successful bypass graft placement proximal to the crossing point) | |||

| Czekajska-Chehab et al. (2005) [6] | 1 | CTCA | LAD artery (superior) and LCx artery |

| 57; male | * Absent LMCA–LAD artery ostium located posterior to the LCx artery ostium in the left aortic sinus | ||

| * Mid-LAD artery (Im) and DgA (Im) | |||

| Yilmaz and Demir (2005) [17] | 1 | Conventional CA | LAD artery and DgA |

| 54; female | * DgA arose at the level of the first septal and diagonal arteries and ramified as a third DgA | ||

| * Both crossing branches contained a stenosis tackled by stenting | |||

| Zegers et al. (2007) [22] | 1 | Conventional CA | Sub-branches of OMB |

| 73; male | * Confirmation of crossing during CABG | ||

| * One sub-branch was Im at the crossing point and was recognized during CABG | |||

| * Grafting of the epicardial crossing sub-branch due to a significant LCx artery stenosis | |||

| Hur et al. (2008) [7] | 1 | CTCA | LAD artery (superior) and LCx artery |

| 55; male | * Absent LMCA–normal origin of the LAD artery from the left aortic sinus and anomalous origin of the LCx artery from the right aortic sinus with an inter-arterial course (acute angle of takeoff and slit-like hypoplastic ostium) | ||

| Shepard et al. (2009) [8] | 1 | CTCA | LAD artery (superior) and LCx artery |

| 43; male | * Absent LMCA–LAD artery ostium located posterior to the LCx artery ostium in the left aortic sinus | ||

| Continentino and Freitas (2011) [9] | 1 | CTCA | LAD artery (superior) and LCx artery |

| 57 (sex not reported) | * Absent LMCA–LAD artery ostium located posterior to the LCx artery ostium in the left aortic sinus | ||

| Andreou et al. (2012) [18] | 1 | Conventional CA | LAD artery and DgA |

| 74; male | * DgA arose as a first DgA and ramified as a second DgA | ||

| Pursnani et al. (2012) [10] | 1 | CTCA | LAD artery (superior) and LCx artery |

| 43; male | * Absent LMCA–LAD artery ostium located posterior to the LCx artery ostium in the left aortic sinus | ||

| Okutucu et al. (2012) [19] | 1 | Conventional CA | Long LAD artery of a type I dual LAD artery variant and DgA |

| 62; female | * DgA was the continuation of the short LAD artery | ||

| Njeim et al. (2014) [23] | 1 | Conventional CA and CTCA | LAD artery (superior) and RM (Im) |

| 63; female | * Single coronary ostium anomaly arising from the right aortic sinus | ||

| * Backward (apex-to-base) reconstitution of the LAD artery from an RVB connected to the proximal common trunk | |||

| * RM was the continuation of a sub-branch of the RVB, which continued as the LAD artery | |||

| Murphy DJ et al. (2017) [11] | 1 | CTCA | LAD artery (superior) and LCx artery |

| 42; male | * Inter-arterial LCx artery with an independent, slit-like orifice and an acute takeoff angle from the left aortic sinus | ||

| Michałowska et al. (2018) [24] | 1 | CTCA | LAD artery and RM (superior) |

| 35; male | * Dilated cardiomyopathy manifested as heart failure; significant mitral valve regurgitation, occlusion of the left internal carotid artery, and ischemic stroke | ||

| Pereira et al. (2019) [12] | 1 | Anatomical pathology | LAD artery (superior) and LCx artery |

| 36; male | * Absent LMCA–LAD artery ostium (tangential) located posterior to the LCx artery ostium in the left aortic sinus | ||

| * Mid-LAD artery (Im) | |||

| * Dilated non-ischemic cardiomyopathy and bicuspid aortic valve with anatomopathological signs of regurgitation (patient underwent heart transplantation) | |||

| Michalak et al. (2019) [13] | 1 | CTCA | LAD artery (interarterial) and LCx artery (pre-pulmonic; superior) |

| 22; female | * Transposition of great arteries | ||

| * The RCA and LCx artery originated from the right-facing sinus, and the LAD artery originated from the left-facing sinus (of the original aorta that was connected to the RVOT) | |||

| * The coronaries were reimplanted in the rightward-facing sinus of the neoaorta (the original pulmonary artery trunk root that was connected to the LVOT before the operation) | |||

| * Inter-arterial course of the LAD artery producing a 60% stenosis | |||

| * Asymptomatic patient; CTCA performed as part of a routine evaluation after arterial switch operation | |||

| Pandey and Sharma (2020) [20] | 1 | CTCA | LAD artery and DgA (superior) |

| 44; male | * Right aortic sinus-connected retro-aortic LCx artery | ||

| Schulze-Zachau et al. (2020) [14] | 1 | CTCA | LAD artery (superior) and LCx artery |

| 73; female | * Absent LMCA–LAD artery ostium located posterior to the LCx artery ostium in the left aortic sinus | ||

| * Anomalous septal branch origin from the LCx artery distal to the crossing point | |||

| Sen et al. (2020) [5] | 1 | Conventional CA and CTCA | LAD artery (superior) and LCx artery |

| 48; male | * Absent LMCA–LAD artery ostium located posterior to the LCx artery ostium in the left aortic sinus | ||

| O’Brien et al. (2020) [15] | 1 | CTCA | LAD artery (superior) and LCx artery |

| 66; female | * Absent LMCA–LAD artery ostium located posterior to the LCx artery ostium in the left aortic sinus | ||

| Ndao et al. (2020) [25] | 1 | CTCA | LCx artery and OMB (superior) |

| 67; male | * History of Bentall procedure due to aortic root dilatation and severe aortic valve regurgitation | ||

| de Jong and Tent (2021) [21] | 1 | CTCA | LAD artery and DgA (superior) |

| 46; male | * DgA originated from the LMCA | ||

| Ferraz Costa et al. (2023) [16] | 1 | CTCA | LAD artery (superior) and LCx artery |

| 45; male | * Absent LMCA–LAD artery ostium located posterior to the LCx artery ostium in the left aortic sinus | ||

| Andreou (present case) | 1 | Conventional CA | LAD artery and DgA |

| 44; male | * DgA arose as a first DgA and ramified as a second DgA | ||

| * Mid-LAD artery (Im) |

Abbreviations: RVB, right ventricular branch; AMB, acute marginal branch; RM, ramus medianus; OMB, obtuse marginal branch; DgA, diagonal artery; PLVB, posterior left ventricular branch; RCA, right coronary artery; LAD, left anterior descending artery; LCx, left circumflex artery; LMCA, left main coronary artery; Im, intramural course; CA, coronary angiography; CTCA, compute tomography coronary angiography; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft surgery; RVOT, right ventricular outflow tract; LVOT, left ventricular outflow tract.

The anomaly has been predominantly diagnosed in male patients (70%), with a mean age of 49.9

Although CACr has not been associated with specific clinical repercussions, knowledge of this anomaly is significant not only for practical purposes when performing coronary artery angiograms, but also for therapeutic purposes, because it may affect the accuracy of identifying the culprit lesion in cases of acute coronary syndrome and the choice and execution of revascularization procedures. The case of crossing LAD and LCx arteries arising independently from the left aortic sinus reported by Sen et al. [5] highlights the challenge of depicting this anomaly using conventional angiography. The authors were only able to demonstrate the LAD artery selectively; therefore, the authors obtained a non-selective view of the left coronary artery system in a left anterior oblique caudal projection, which showed that the LAD and LCx arteries had switched positions with the LCx artery depicted to the “left” of the LAD artery. The LCx artery was subsequently selectively engaged with a counterclockwise rotation, hence an anteriorly directed catheter. The anatomy was clarified through CTCA, which showed the crossing proximal courses of the LAD and LCx arteries, with the LAD artery arising posterior to the LCx artery. In cases of an absent left main coronary artery without crossing between the LAD and LCx arteries, the ostium of the LAD artery generally has a more anterior origin than the ostium of the LCx artery. Failure to selectively engage these vessels using the usual technique and catheters should alert the physician to the possibility of proximal crossing between them. Accordingly, suspicion of this specific anomaly should arise in case the ostium of the LAD artery is selectively engaged with a clockwise rotation, hence a posteriorly directed catheter, perhaps with a shorter secondary curve; thus, an upward pointing tip, such as a Judkins Left 3.5 catheter. Finally, the ostium of the LCx artery is selectively engaged with a counterclockwise rotation, hence an anteriorly directed catheter, perhaps with a longer secondary curve; thus, a more horizontal tip, such as a Judkins Left 4.5. Of course, a full depiction of the anomaly would require catheter engagement of the ostia of the LAD and LCx arteries and simultaneous visualization of these vessels.

Furthermore, in the case of acute coronary syndrome owing to an occlusion of a DgA leaving an avascular area at the anterolateral aspect of the left ventricle, the difficulty in identifying a stump-like thrombotic occlusion of a normally arising DgA across the LAD artery should alert the physician to the possibility of occlusion in a DgA arising proximal and contralateral to the origin of other diagonal branches and a crossing of the LAD artery. Therefore, knowledge of this specific anomaly facilitates the correct diagnosis and revascularization procedure. In patients with CACr who are potential candidates for surgical revascularization, the possibility of intramural coursing of significantly stenosed crossing branches needing revascularization should be investigated before surgery because intramural coronary branches, which may not be readily identifiable on conventional CA, are not amenable to bypass grafting. Adjunctive imaging modalities possess a higher sensitivity than invasive CA in detecting intramyocardial coronary arteries, such as CTCA, and may be employed for such a purpose. If a severely narrowed crossing coronary artery/branch cannot be bypassed because of its intramural course, the surgeon may create an arterio-arterial shunt at the point of the crossing, provided the other branch does not contain a flow-limiting stenosis. If this is not possible, stent angioplasty may be selected as a more suitable revascularization option, should leaving such intramyocardial branches unrevascularized be judged unacceptable. Of course, it is currently unknown whether any specific circumstances, currently unknown but potentially present in the area of vessel crossover, pose particular risks if stent angioplasty is performed in that specific area.

Although CACr has not been linked to specific clinical repercussions, it may be associated with clinically relevant, functional coronary artery abnormalities. However, to our knowledge, this potential association has yet to be investigated in any prior study. For example, in the clinical context of myocardial ischemia with non-obstructive (

Traditional knowledge teaches that proximal coronary artery stems develop following fusion of the multiple endothelial strands emerging from the aortic peritruncal plexus and penetrating the aortic wall of the facing sinuses [29]. Since it would be difficult to hypothesize an altered fusion process of the multiple endothelial strands that would result in the formation of crossing channels, the anomaly of crossing LAD and LCx arteries challenges this “ingrowth” model of proximal coronary artery stem development. Given newer evidence documenting that the coronary ostia and most proximal part of the coronary artery stems are formed by limited outgrowth of the aortic endothelium through endocardial sprouting, it may be considered more plausible that independent origin of the LAD and LCx arteries from the left aortic sinus with crossing between their more proximal segments results from a defective outgrowth mechanism [30].

Overall, knowledge of the anomaly and being an astute observer are necessary to diagnose CACr accurately. However, diagnosing crossed LAD and LCx arteries arising from separate ostia remains challenging. Depicting the LCx artery to the “left” of the LAD artery in non-selective conventional angiography in a left anterior oblique caudal projection helps the physician suspect the anomaly [5]. Yet, catheter engagement of the ostia and simultaneous visualization of these vessels would be necessary to depict crossed proximal courses. Alternatively, the anomaly can be reliably defined through CTCA. Patients who present with myocardial ischemia and are diagnosed with CACr should have their angiogram scrutinized for signs of crossed coronary arteries with an intramyocardial course. Such a course is typically diagnosed via the angiographic “milking effect” and a “step down–step up” phenomenon induced by systolic compression of the tunneled segment. An intracoronary bolus dose of vasodilators, such as nitroglycerin or isosorbide dinitrate, can significantly improve diagnostic sensitivity. Yet, the presence of the “step down–step up” phenomenon without angiographic “milking” or a corkscrew appearance of either or both crossed coronary arteries should prompt investigation using CTCA to visualize an intramyocardial coronary artery course more sensitively and comprehensively than conventional angiography. In the case of non-obstructive (

We have presented an overview of all published CACr cases, a rare but clinically important anomaly in intrinsic coronary artery anatomy. This anomaly is presently considered benign. However, it is possibly associated with clinically relevant, functional coronary artery abnormalities such as a spasm in the area of vessel crossover or segments with an intramyocardial course; however, these have yet to be proven. Knowledge of the particularities of crossing LAD and LCx arteries, the most frequently encountered pattern, facilitates the correct diagnosis through conventional CA. However, the crossing of these arteries can be especially challenging to depict. This way, the erroneous diagnosis of ostial occlusion or absence of either of the two arteries is avoided. Meanwhile, knowledge of CACr also facilitates the identification of the culprit lesion during coronary angiography and, therefore, the revascularization procedure in patients presenting with acute coronary syndrome. Moreover, the CACr diagnosis should alert the physician to possible intramyocardial coursing of one or both crossing branches, something that should be considered when planning revascularization procedures, whether percutaneous or surgical. Computed tomography CA can not only reliably depict this anomaly but can also reveal the arterial spatial relationship at the point of crossover and depict any intramyocardial coursing that may not be apparent during conventional angiography.

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online Supplementary Material.

AYA: Writing-review & editing, Writing - original draft, Investigation, Data curation, Conceptualization. The single author read and approved the final manuscript. The single author has participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee(s) and with the Helsinki Declaration (as revised in 2013). Written informed consent for the publication of this Case Report was not obtained from the patient or the relatives after all possible attempts were made. The information provided in the article have been sufficiently anonymized so as neither the patient nor anyone else could identify the patient.

I want to express my gratitude to the nursing and radiology staff at our catheterization laboratory for their dedication and hard work which have been instrumental in providing the best possible care to our patients.

This research received no external funding.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/HSF47499.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.