1 Laboratory of Molecular Genetics, Epigenetics and Longevity, Institute of Molecular Biology “Roumen Tsanev”, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, 1113 Sofia, Bulgaria

Abstract

Ageing comprises a cascade of processes that are inherent in all living creatures. There are fourteen general hallmarks of cellular ageing, the majority of which occur at a molecular level. A significant disturbance in the regulation of genome activity is commonly observed during cellular ageing. Overall confusion and disruption in the proper functioning of the genome are also well-known prerogatives of cancerous cells, and it is believed that this genomic instability provides a direct link between aging and cancer. The spatial organization of nuclear DNA in chromatin is the foundation of the fine-tuning and refined regulation of gene activity, and it changes during ageing. Therefore, chromatin is the platform on which genes and the environment meet and interplay. Different protein factors, small molecules and metabolites affect this chromatin organization and, through it, drive cellular deterioration and, finally, ageing. Hence, studying chromatin structural organization and dynamics is crucial for understanding life, presumably the ageing process. The complex interplay among DNA and histone proteins folds, organizes, and adapts chromatin structure. Among histone proteins, the role of the family of linker histones comes to light. Recent data point out that linker histones play a unique role in higher-order chromatin organization, which, in turn, impacts ageing to a prominent degree. Here, we discuss emerging evidence that suggests linker histones have functions that extend beyond their traditional roles in chromatin architecture, highlighting their critical involvement in genome stability, cellular ageing, and cancer development, thereby establishing them as promising targets for therapeutic interventions.

Keywords

- linker histones

- ageing

- chromatin

- genome stability

- cancer cell

- yeast

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae

Ageing is generally perceived as a complex decline of cellular and organismal functions over time and is the main factor for disease susceptibility [1]. Many cellular processes, such as inflammation, apoptosis and autophagy, have been assigned to ageing. The interplay among the plethora of protein factors lays the basis of these processes. Therefore, ageing is accepted as strongly dependent on specific genes’ regulation and dysregulation [2]. In recent decades, intensive efforts have been made to unravel the cellular and molecular events that might cause the organism’s ageing [3]. It is not surprising, then, that there is an overlapping between cellular pathways that promote ageing and those linked to cancer, neurodegeneration and cardiovascular disorders as well as metabolic syndromes [4, 5, 6].

Chromatin is the dynamic scaffold in which DNA is stored and organized within the eukaryotic nucleus. Beyond its structural role, chromatin’s organization extensively influences genome functionality. This intricate relationship, where chromatin structure reflects gene activity, underscores its role in determining cellular identity and metabolism [7]. Initially conceptualized in the late 19th century as the solution to packaging genetic material within the confined nucleus space [8], chromatin’s functional significance emerged prominently in the early 21st century as scientists unravelled how its organization directly influences gene expression [9]. It is well established today that chromatin organization and dynamics are pivotal to understanding genome regulation and activity. The primary drivers of chromatin architecture are histones and non-histone proteins, which assemble DNA into a hierarchical structure with multiple levels of compaction [10].

At the foundational level of chromatin organization lies the nucleosome, the best-characterized structural unit. Each nucleosome comprises 146 base pairs of DNA wrapped in a left-handed superhelix around a histone octamer, composed of two molecules, each of histones H2A, H2B, H3, and H4. These core histones, enriched with the positively charged amino acids lysine and arginine, interact electrostatically with the negatively charged DNA, stabilizing the nucleosome while allowing dynamic remodelling for DNA accessibility [10]. The fifth class of histones, known as linker histones, is associated with the linker DNA, a feature that gives them their name. Linker histones, such as histone H1, bind to nucleosomal core particles and the linker DNA at sites near the nucleosome entry and exit points (Fig. 1) [11, 12]. The core histones, 160 bp-long DNA and the linker histones compact together. This structure is referred to as a chromatosome [13]. Upon binding the linker histone to the linker DNA, the polynucleosomal fibre folds in a 30 nm fibre [10, 14]. The principles of organization of the following levels of chromatin compaction – the so-called “30 nm fibre”, loops, domains, and chromosome territories – are poorly understood, regardless of the extensive study. It is thought that structurally, chromatin is assembled in hierarchically ordered levels of compaction, organized in functionally reliant domains where linker histones seem to play an important role [15].

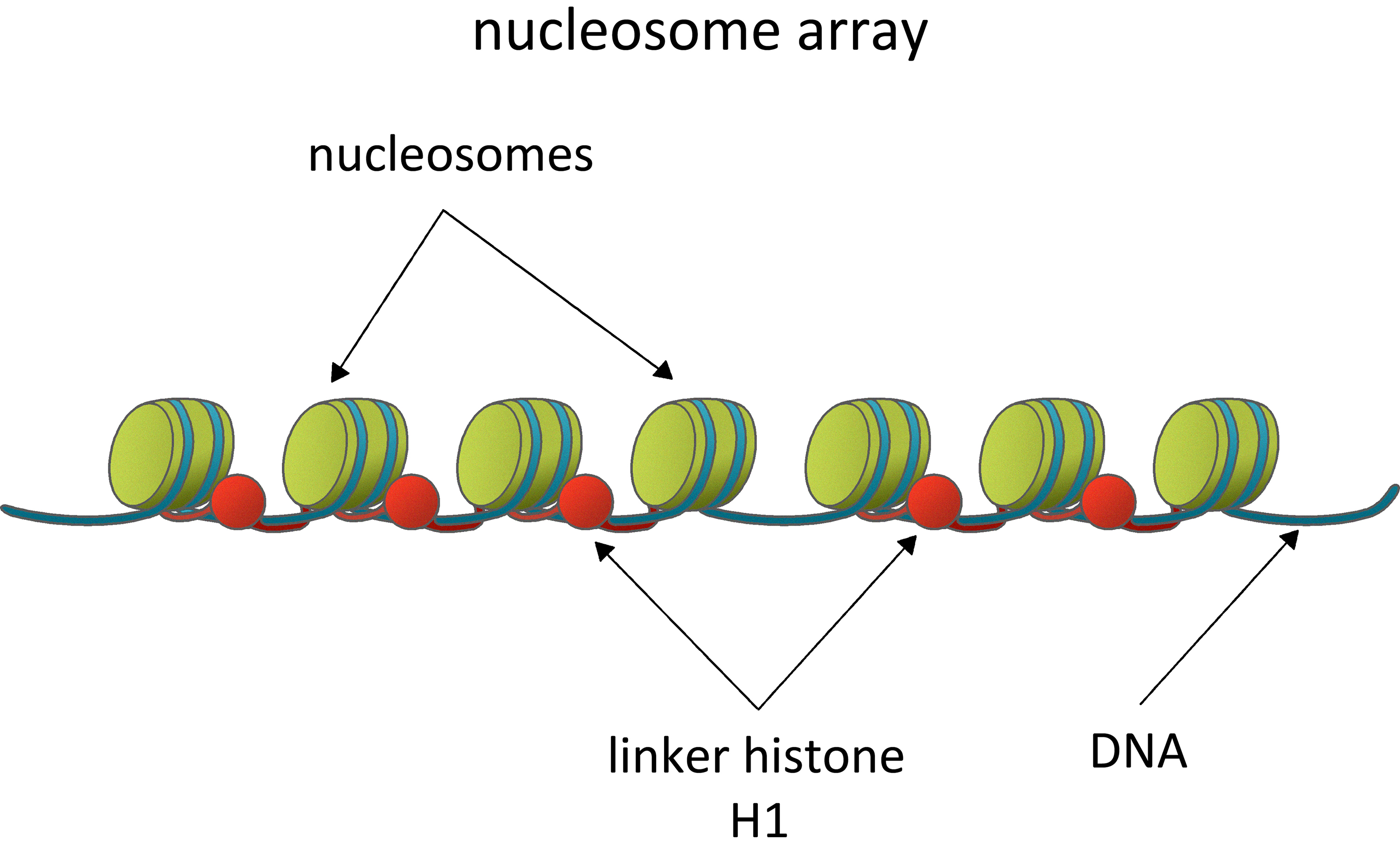

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Nucleosomes: fundamental units of chromatin organization and gene regulation. Nucleosome arrays as the fundamental unit of chromatin organization, comprising regularly spaced nucleosomes and linker DNA. They have a critical role in regulating gene accessibility and transcriptional activity through dynamic structural. interactions and the influence of linker histone H1. Figure created using Adobe Photoshop CC2019 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

In the compacted chromatin environment, DNA is not physically accessible for the transcriptional factors. Therefore, the regulation of gene activity is performed at several levels, among which epigenetic mechanisms are fundamental [16]. The transcriptional machinery gains access to DNA only after specific DNA and histone covalent modifications. These modifications are recognized by highly specialized chromatin remodelling complexes, which transform local chromatin into an active or repressive state. Chemical modifications on DNA and histones, together with the chromatin remodelers, are among the leading players in the epigenetic regulation of gene activity. This form of regulation encompasses heritable changes in gene expression that do not involve alterations to the underlying DNA sequence, primarily mediated through modifications to chromatin structure. By influencing how tightly or loosely DNA is packaged within chromatin, these epigenetic mechanisms play a critical role in determining gene accessibility and transcriptional activity, thereby shaping cellular identity and function [17, 18]. Recent data highlight the role of linker histones in maintaining genomic stability, mainly through interactions with critical proteins such as BRCA1. For example, H1 has been identified as a critical player in ensuring the stability of the replication fork during DNA replication, emphasizing its importance in preserving genome integrity [19]. This relationship underscores the importance of chromatin dynamics in cellular responses to DNA damage and highlights potential avenues for cancer research focused on enhancing genomic integrity through targeted interventions.

The four core histones, H2A, H2B, H3 and H4, are chromatin’s fundamental

building blocks. They dynamically alternate closed with open chromatin

structures, thus regulating the transition between transcriptionally active

genomic loci [20]. The fifth class of histones, the linker histones, are located

between two adjacent nucleosomes [21]. However, their functions in chromatin are

not fully understood. Their chemical structure is represented by short N-terminal

and long C-terminal tails surrounding the central globular “winged helix” domain

(Fig. 2). The winged helix is comprised of a helix-turn-helix motif [22]. The

three helixes in the globular domain are designated as H1, H2 and H3 or

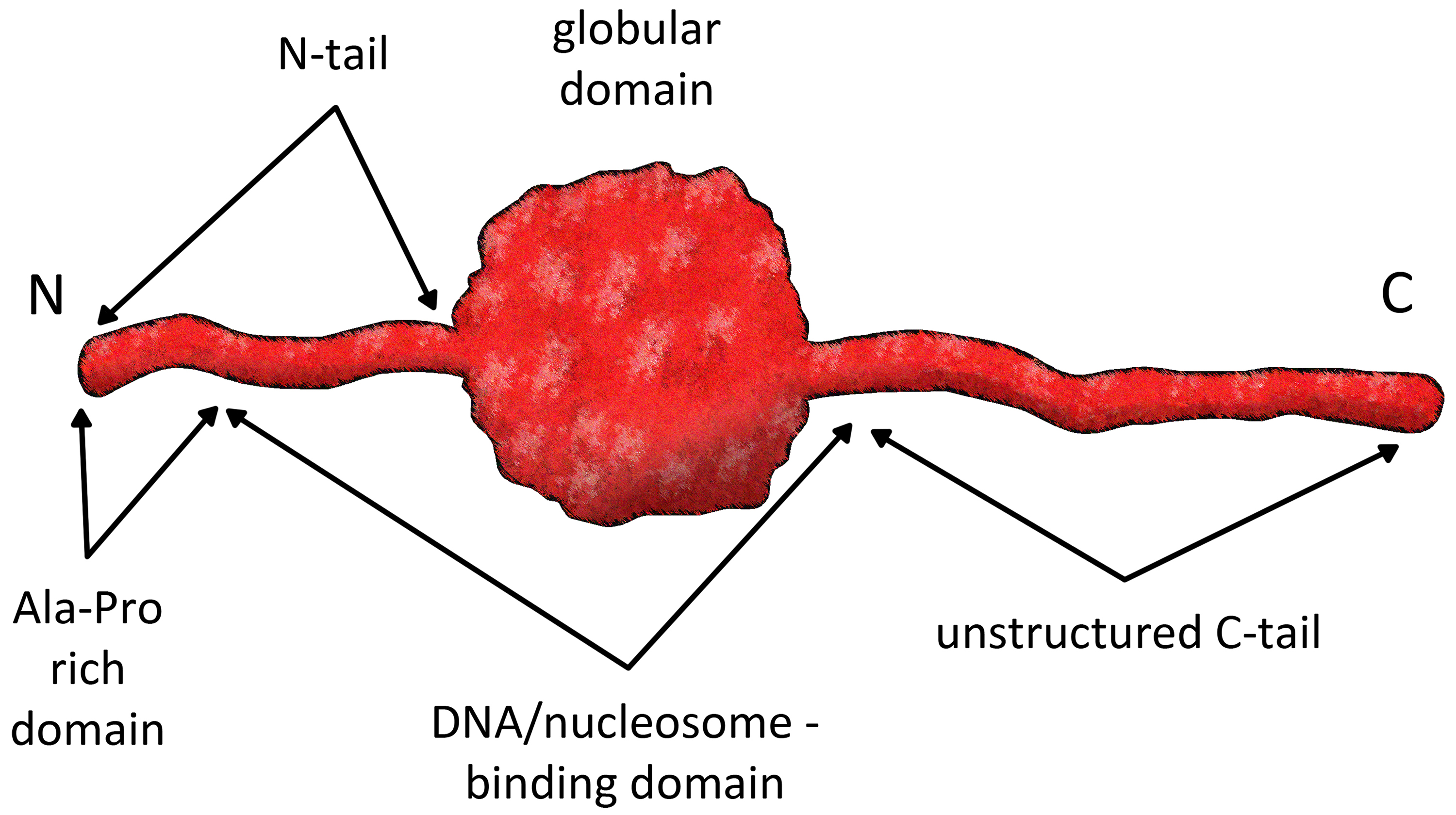

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

General protein structure of linker histones. The structural domains of linker histones are key to their function, as they contribute to the formation of higher-order chromatin structures that are essential for maintaining genome stability and regulating gene expression. Figure created using Adobe Photoshop CC2019 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

The linker histones are a highly conserved protein family, even though not as much as the core histones, and comprise many variants. Molecular analyses suggest that the origin of the proto-linker histone proteins can be traced to eubacteria, contrasting the archaea-derived core histones [12]. In particular, the winged helix motif of the globular domain is characteristic of all metazoan linker histone molecules, and it is well conserved through evolution in fungi, plants and animals. It also appears in several divergent lines of protists. Contrasting the conservation of the globular domain, the N- and C-terminal domains are highly heterogeneous in amino acid sequence and length. For example, the linker histones in metazoans and other multicellular eukaryotes are a diverse group of developmentally differential regulated and expressed histones. Many family members are tissue- and cell-type specific, such as the bird erythrocyte histone H5 and the sperm H1-related protamine-like (PL-1) proteins [28, 29]. Concerning evolutionary diversity, the data show a correlation between the complexity of the organism and the number of linker histone variants it possesses.

In organisms such as Drosophila melanogaster and Physarum polycephalum, only one variant of the linker histone H1 is present [30, 31]. Interestingly, the average number of linker histone variants in higher eukaryotes varies between 4 and 7, but 11 are reported in mammals. Among these, some are expressed during the S phase of the cell cycle, and they are the histones H1.1-H1.5, characteristic of somatic cells. In contrast, H1.0 (often referred to as H1°) and H1.X are differentially expressed in somatic cells. Gametes and their precursors also have specific differentially expressed histones - H1t, H1T2 in testicular cells, and H1oo in oocytes [32]. The expression of histone variants varies throughout the various cell types and the different phases of the cell cycle [33]. The size of linker histone variants differs from 193 to 345 amino acids, for the shortest - H1.0 and the longest - H1oo, respectively. The remaining linker histone variants are much more homogenous in length and vary between 206 and 233 amino acid residues. Avian erythrocyte linker histones, for example, consist of 6 variants resembling the mammalian ones and vary in length between 217 to 224 amino acids [34]. The avian and somatic mammalian linker histone subtypes have a high similarity among their globular domain, and particular homology is present between H5 and H1.0 [35]. In humans, there are as many as 11 variants of linker histones [36, 37]. These variants exhibit differences in their ability to organize the chromatosome [38], influence the packaging of the chromatin fibre [39, 40], and regulate transcription [41].

Extensive research has been conducted on metazoan linker histones, but other eukaryotic taxa have been neglected. Despite this discrepancy, many histone H1 variants, homologues and similar proteins have been isolated and characterized from broad spectra of eukaryotic taxa. Such proteins have been found inside animals, plants, fungi and various protozoans [12, 35].

Until recently, the functions of linker histones (H1 and related proteins) have been thought to be limited to sealing two neighbouring nucleosomes to make the so-called “nucleosome array”. Based on this deterministic idea, people expect different variants of the linker histones to encompass different sizes of inter-nucleosomal (linker) DNA. It was proven beyond doubt that the linker histones build up and maintain higher-order chromatin structures above the nucleosome arrays [14, 42, 43]. Moreover, similar to the core histones, the linker histones possess epigenetic functions. And because of their exact position, these histones have specific functions outside the nucleosomes, which merit special scientific efforts.

H1 histones have long been considered architectural proteins of chromatin that are predominantly involved in the building of the proper structuring of chromatin. Previous models suggested that the linker histones promoted chromatin condensation and thus facilitated the formation of repressive chromatin. However, later results suggested that H1 variants execute various specific nuclear functions [10, 35, 44]. Nowadays, it is generally accepted that the linker histones modulate the accessibility of DNA for biological processes like DNA replication and gene transcription by binding to nucleosomes [44]. Recent discoveries further add new data to linker histones’ structural and functional importance, thus suggesting new roles for them [44, 45, 46]. The linker histones’ oldest and best-understood functions were indeed involved with the compaction of chromatin and its participation in maintaining the higher-order chromatin structures [13, 47, 48] and transcriptional repression [49, 50, 51]. While it was demonstrated that the polynucleosomal strand was not able to fold to a certain extent without linker histones spatially, their binding to the linker DNA was accepted as a fundamental prerequisite for the organization of chromatin to the well-known 30 nm fibre [8, 47, 48].

One of the earliest investigations of the functions of histone variants showed that the rate of initiation of RNA polymerase was correlated to both type and amount of linker histone present and that the level of repression of RNA polymerase was determined by the capabilities of different linker histone variants to induce higher-order chromatin structures formation [11]. Further evidence of linker histone variants’ specific functions was found at different times and rates of expression [52]. Different linker histone variants were shown to have different capabilities of chromatin condensation, which was correlated with the differential depletion or accumulation of specific H1 variants in sites of different nuclear activities. The general abundance of total H1 in the constitutive and facultative heterochromatin illustrated its deep involvement in the compactization and organization of chromatin and its participation in regulating gene expression. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that H1 variants could induce chromatin condensation without preventing chromatin remodelling complexes from accessing it [53]. H1.1 and H1.2, for example, were determined as weak condensers, while H1.3 was intermediate, and H1.0, H1.4, H1.5, and H1.x were strong condensers. There is an accumulation of evidence suggesting that specific H1 variants were involved directly in the individual regulation of specific genes [54]. RNA interference depletion of each H1 variant in breast cancer cells led to altered gene expression [55]. The knockout of H1.2 resulted in cell proliferation arrest induced by repression of cell cycle genes, whereas the knockout of H1.4 resulted in cell death for some cell lines. It has been shown that the expression levels of specific linker histone variants changed during cell differentiation and induced pluripotency. While H1.4 and H1.2 showed relatively stable levels, H1.0 levels increased during differentiation, whereas H1.1, H1.3 and H1.5 increased during inducement of pluripotency [56]. In line with these findings, recent data has highlighted the pivotal role of linker histone variants in maintaining tissue and organ homeostasis. Specifically, histone H1.0 has been identified as a critical regulator. By promoting global chromatin compaction, H1.0 orchestrates cytokine-driven fibroblast contraction and proliferation, thereby playing a central role in controlling fibrosis in vivo. This evidence underscores the distinct functional significance of histone H1.0 in mediating cellular responses to mechanical and chemical stimuli, establishing it as a key molecular player in tissue remodeling and stress adaptation [57].

Interestingly, the properties of the linker histone variant H1T challenge the classical understanding that histones of the H1 family primarily function to compact chromatin and act as gene repressors. Contrary to this, H1T has been shown to induce chromatin relaxation in specific contexts rather than compaction. Hayakawa et al. (2020) [58] demonstrated that H1T is predominantly localized in the nucleolus, targeting rDNA repeat regions condensing chromatin to repress pre-rRNA expression. However, in the non-repetitive genic regions of the nucleoplasm, H1T displays a contrasting role. Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing revealed that H1T localizes around transcriptional start sites, inducing chromatin decondensation and increasing the expression of target genes. Knockdown and overexpression results further confirmed that H1T facilitates chromatin relaxation, which is linked to gene activation [58].

Additionally, H1T was found to co-localize with the transcription factor SPZ1 in genic regions. These findings highlight the dual functionality of H1T: while it compacts chromatin in rDNA repeats to repress transcription, it relaxes chromatin in genic regions to promote gene expression. This evidence underscores the remarkable versatility of linker histone functions in regulating chromatin dynamics and gene activity. Other studies have also shown that H1 could finely tune transcription in a locus-specific manner [59, 60]. All these characteristics position the linker histone as a significant player in preserving genome stability, which is essential for chromatin organization and how cells respond to environmental stimuli during ageing.

These discoveries reveal the expanding spectrum of roles linker histones play, transcending their conventional association with chromatin compaction to encompass diverse regulatory functions that adapt to cellular and genomic contexts.

Chromatin is a highly dynamic structure showing signs of significant organizational changes during ageing [61]. Global histone loss as ageing progresses is one of the most studied models, and it has been proven in many experimental models like yeast, worms, and mammals to contribute significantly to genome instability [51, 52]. A substantial part of histones is lost from the chromatin during cellular ageing. With time passing, chromatin is losing its core histones but is losing linker histones at an even higher degree due to their higher mobility and sensitivity to proteolytic degradation [62]. As linker histones are among the significant players in maintaining the higher-order chromatin, their loss would undoubtedly lead to disruption of its proper organization (Fig. 3). In the study titled “Pan-cancer atlas of somatic core and linker histone mutations”, Bonner et al. [63] provide a comprehensive analysis of somatic mutations in core and linker histone genes across 12,743 tumours from pediatric, adolescent, and adult cancer patients. This landmark research reveals that approximately 11% of tumours harbour somatic histone mutations, with exceptionally high rates observed in chondrosarcoma (67%) and pediatric high-grade glioma (over 60%). The study highlights the emerging role of linker histone mutations, particularly in H1, associated with chromatin decompaction and altered gene expression patterns that can drive oncogenic transformation. Linker histones are crucial for maintaining chromatin structure and regulating transcription, and their mutations have been linked to both cancer development and ageing. As organisms age, the accumulation of somatic mutations—including those in linker histones—can disrupt standard chromatin architecture, leading to transcriptional misregulation characteristic of many age-related diseases and cancers (Fig. 3A). The findings from Bonner et al. [63] underscore the importance of linker histones in the context of ageing and cancer, suggesting that their mutations contribute to tumorigenesis and reflect broader epigenetic changes associated with ageing processes. This connection emphasizes the need for further research into how these alterations influence chromatin dynamics and their potential as therapeutic targets in cancer treatment [44, 57, 64]. As illustrated in Fig. 3A, the loss of many histone proteins, including linker histones, results in an open chromatin fibre in various genome regions of aged cells, activating genes typically silenced in young cells. Furthermore, Fig. 3B demonstrates that the sensitivity of chromatin to Micrococcal nuclease (MNase) is heightened in aged cells, suggesting that the general size of chromatin loops increases with ageing, as evidenced by the Chromatin Comet Assay (ChCA) [43].

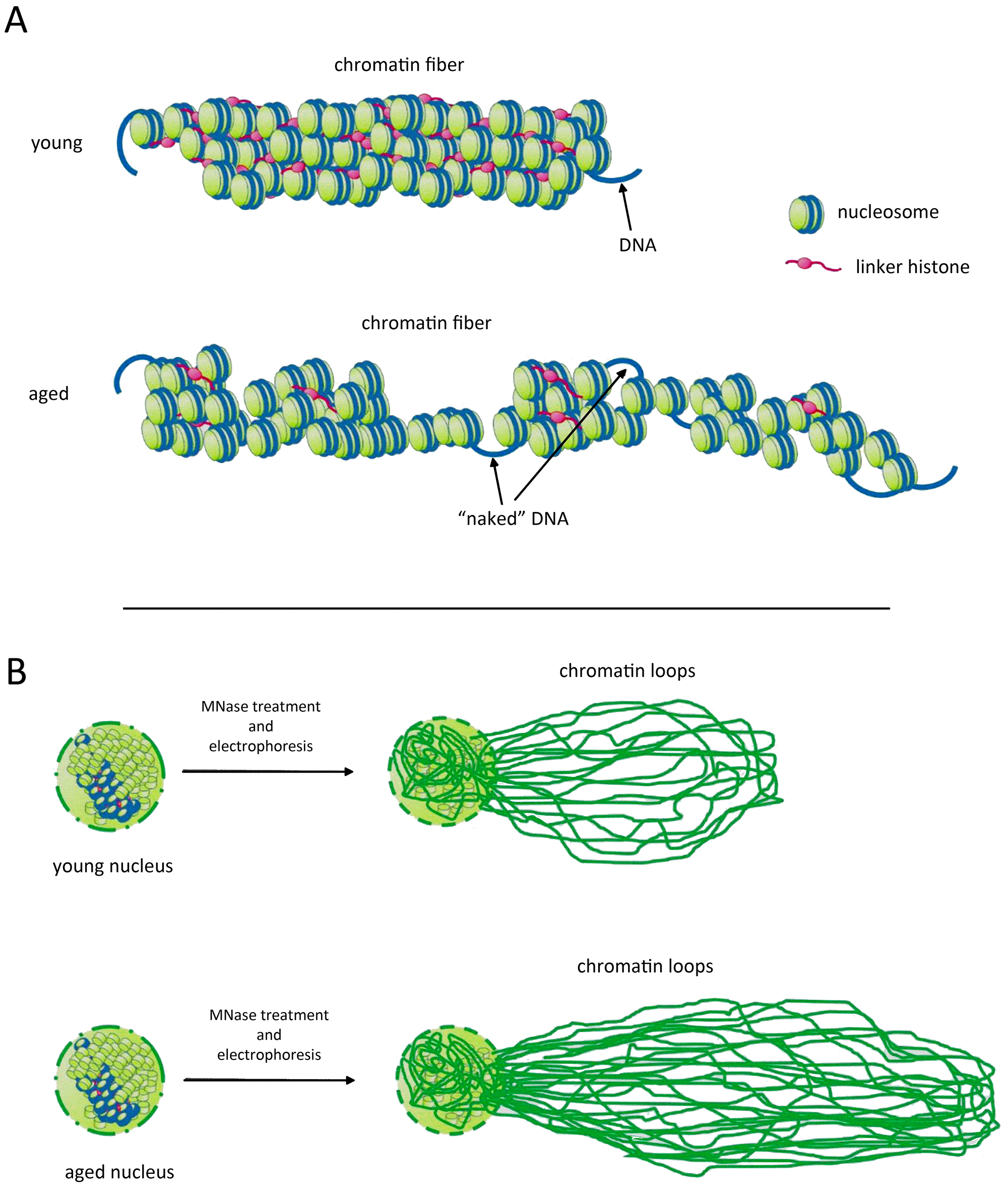

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Higher-order chromatin structures become disordered during ageing. (A) Due to ageing, many histone proteins, including linker histones, are lost. Chromatin fiber in many genome regions of aged cells is open and permits activation of genes whose expression is “forbidden” in young cells. (B) The sensitivity of chromatin to Micrococcal nuclease (MNase) is higher in aged cells, thus leading to longer chromatin loops, evidenced by Chromatin Comet Assay (ChCA). Figure created using Adobe Photoshop CC2019 (Adobe Systems Inc., San Jose, CA, USA).

Interestingly, the loss of histones in S. cerevisiae is linked to global transcriptional upregulation, which can explain why, even though histone protein levels decrease with age, histone transcripts are upregulated [65]. It has also been shown that the histone protein levels can be increased due to the overexpression of histones, resulting in a longer lifespan in yeast [66]. This has also been shown in C. elegans, where overexpression of histone H4 due to overexpression of Heat shock factor–1 (HSF-1) has resulted in a prolonged lifespan [67]. Several studies explain the global loss in core histones during ageing. Experiments on old IMR90 fibroblasts have suggested that the observed histone protein loss might be due to the decreased biogenesis of histones H3 and H4 caused by the stress exerted by the shortening of the telomeres (e.g., [68]). Transcriptome analyses showed significant downregulation of histones H1, H2A, H2B, H3, and H4 in the aged retinal pigment epithelium (RPE)/choroid, including critical components of the histone locus body (HLB) complex, which is essential for histone pre-mRNA processing [69]. A similar loss of canonical histones associated with ageing has been found in activated naive CD4+ T cells. Transcriptome analysis using RNA-seq has shown that T cells of older adults (aged 65–85 years) had lower expression levels of core histone genes compared to younger adults (aged 20–35) [70]. Loss of the histone variant H2A.Z has also been associated with oxidative stress, DNA damage accumulation, protein oxidation, and damage to mitochondria and neuromuscular junctions, leading to premature muscle ageing and a reduced lifespan [71].

Since 1997, the loss of heterochromatin has also been established as a well-known ageing model [72]. Typically, with the progress of ageing, a loss of heterochromatin is observed, which influences changes to the global nuclear organization and affects how heterochromatin-associated genes are expressed [73]. Heterochromatin is a very compact structure; typically, more inactive genes reside there [74]. When its structure is disrupted, a general loss of transcriptional silencing is observed, particularly associated with ageing. An increase in longevity has been achieved by reversing this process, and by minimizing the transcriptional silencing, ageing is accelerated [75]. Heterochromatin regions are deprived of histone acetylation, resulting in gene silencing. Sirtuins are a group of proteins that possess deacetylase properties. Therefore, if the genes encoding Sirtuins, like the SIR2 found in yeast, are deleted, this will result in reducing the life span. The same will be achieved using histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors.

On the contrary, if there is an overexpression of the genes encoding Sirtuins, an increase in the lifespan may be achieved [76, 77]. In premature ageing syndromes like Hutchinson-Gilford progeria and Werner syndrome, there is a global loss of heterochromatin combined with disrupted heterochromatin structure [78, 79]. There is a common paradox regarding the loss of heterochromatin theory of ageing. With this event, senescence-associated heterochromatin foci (SAHF) are also formed. These are heterochromatin domains localized in senescent cells at sites of genes, which promote proliferation [80]. The proposed mechanism by which these foci are formed links the age-associated decondensation of heterochromatin in senescent cells and the turning of euchromatin regions into clustered heterochromatin, which implies a redistribution of heterochromatin [81].

Due to the global loss of histones and the loss of heterochromatin, there is an observed increase in retrotransposon mobility, creating a model of ageing by retrotransposition, suggesting that the retrotransposable elements induce ageing phenotypes by dysregulating the genome’s structure [82, 83]. Models of ageing have shown an age-associated increase in expression of retrotransposable elements [84], and on the contrary, suppression of Alu elements transcripts has reversed the phenotype [85]. This higher level of retrotransposable elements has also been observed in diseases linked to ageing, like cancer [86] and neurodegeneration [87, 88]. Oocyte ageing is also linked to heterochromatin loss, which activates specific retrotransposons, resulting in DNA damage and impaired oocyte maturation. Using azidothymidine (AZT) in older oocytes to inhibit the retrotransposon reverse-transcriptase has proven to reverse their maturation defects and restore the DNA reparation machinery activity [89].

Recent data has also implicated the role of three-dimensional genome organization in physiological ageing. Ma et al. [90] have shown that old bone marrow progenitor (pro-) B cells have a distinguishable three-dimensional chromatin organization compared to young (pro-) B cells, which leads to age-associated impairment of B lymphopoiesis.

It was proven beyond doubt that the linker histones are important for higher-order chromatin folding and are essential for mammalian embryogenesis [91]. However, this role seems negligible to a certain extent. There are eleven subclasses of linker histones in mammals [92]. For example, deleting anyone or even two of the genes encoding different linker histone variants in mice generated no obvious bold phenotypes [59, 93]. Nevertheless, linker histone H1 is essential in chromatin folding in vitro. Mouse embryonic stem cells null for three H1 genes had 50% of the average level of H1. The low quantity of H1 caused dramatic chromatin structure changes in the cellular nuclei, including decreased global nucleosome spacing, reduced local chromatin compaction, and decreased content of certain core histone modifications. Surprisingly, the expression of only a tiny number of genes was affected in the knockout cells. The global DNA methylation was unchanged in these cells, null for three H1 genes. However, methylation of specific Cytosine-Phosphate-Guanine sites (CpGs) within the regulatory regions of some of the H1-regulated genes was reduced. Therefore, linker histones could participate in epigenetic regulation of gene expression by influencing specific DNA methylation in some regions [59]. The significance of the linker histones as epigenetic regulators was confirmed by its contacts with chromatin silencing histone modification H3K27me3 [94]. As specific DNA methylation is one of the bold hallmarks of ageing, it is tempting to assume that linker histones can participate in cellular ageing by influencing DNA methylation patterns. Other authors proved the loss of H1 during cellular senescence [95], thus suggesting an unexpected role of these histones in maintaining the cellular senescent phenotype by modulating the interactions among DNA, histones and a high-mobility group of proteins, HMGs.

Senescence and differentiation have similarities concerning gene expression and

chromatin structure reorganization [5, 6, 96]. Recent data highlight the

importance of higher-order chromatin structure during tumorigenesis and

unambiguously point to the critical role of H1 in the silencing of gene

expression of embryonic genes during differentiation, which, when H1 is lost or

with reduced activity, leads to tumorigenesis [97, 98, 99]. These authors unveil the

long-suspected role of H1 as a bona fide tumour suppressor. Further,

they prove that mutations in H1 drive malignant transformation through

three-dimensional genome reorganization [98]. The last is implicated in the

misregulation of gene expression and epigenetic regulation of the overall genome,

leading to detrimental consequences for the cells. Recently, attention has been

given to changes in histone gene expression during senescence. Changes in histone

gene expression have been assessed during cell differentiation, but changes in

histones also occur in the chromatin during ageing. Interestingly, in mice

lacking the H1 gene, age-dependent alterations in silencing the human

An intriguing role of linker histones has been recently proposed, named the non-nuclear and non-epigenetic role of H1 in neurodegeneration [64]. It highlights previously reported data about linker histones’ predominant accumulation in the cytoplasm of neurons during neurodegeneration [101, 102]. New perspectives in the studies of H1 roles in ageing and neurodegeneration are opened, outside their roles as structural chromatin proteins, but even beyond as signalling molecules for induction and fine control of specific cellular processes [92, 103]. This outlook deserves special attention and calls for further investigations.

One especially important differentiation-associated histone that changes during cell divisions and has been well-documented in numerous cell and tissue systems is the linker histone variant H1° [104]. Interestingly, the relative proportion of histone H1°, present in the chromatin of nondividing and terminally differentiated cells, increases with age [105]. With the help of different cell cultures, it was shown that this linker histone variant accumulated during the process of differentiation [104, 106, 107]. Significant for developing new cancer therapies is that the quantity of this histone has an opposite correlation with the de-differentiation of cells. In numerous tumours, the quantity of this histone decreases following the tumour stage progression [98, 99]. A recent study has shown that restoring the levels of H1° in tumour cells through using Quisinostat – a potent HDAC inhibitor, has hindered the cancer cells’ ability to self-renew, therefore haltering tumour maintenance [108].

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae is one of the best model organisms for ageing research. In early 1959, Mortimer and Johnston [109] observed that a single mother cell of the budding yeast S. cerevisiae has a limited reproductive ability, thus marking one of the very first research data on the molecular mechanisms of ageing. Notably, many pathways conserved from yeast to humans are relevant to understanding ageing and disease mechanisms [110, 111, 112]. This includes nutrient signalling, cell cycle regulation, DNA repair mechanisms, mitochondrial homeostasis, lipostasis, protein folding and secretion, proteostasis, stress response, and regulated cell death [113]. The awareness that pathways related to human senescence display a high degree of conservation in S. cerevisiae has promoted the use of yeast to understand signalling pathways and identify molecular mechanisms involved in ageing. In addition, yeast-ageing phenotypes are surprisingly similar to human post-mitotic cellular ageing. In addition, S. cerevisiae cells are the type of organism that allows differentiation between replicative and chronologically ageing cells [114, 115].

The yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae has been the “driving horse” of molecular biology research. Many cellular molecular mechanisms, such as biochemical and mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways, have been initially discovered and thoroughly studied in these yeasts. This is especially true for the research in chromatin biology. The data on S. cerevisiae revealed the basic principles of chromatin organization and dynamics, which are all relevant to higher eukaryotic cells. Yeast possesses almost the same core histone proteins that wrap DNA in nucleosomes, making nucleosome arrays and chromatin loops with sizes close to human cells [14]. However, in addition to these similarities, S. cerevisiae chromatin shows some differences [116], which include a relatively different linker histone as a protein structure.

The presence of linker histone or histone-like proteins in the yeast S.

cerevisiae has been controversial and sharply debated for decades. The existence

of such was rejected for a long time. A study in the 80s dismissed the

possibility of the existence of yeast linker histone, stating that the only known

H1-like protein in S. cerevisiae is the mitochondrial DNA binding

protein – HM [117]. Despite the present doubt about the presence of linker

histones in yeast, an article from 1997 reported its existence [118]. The yeast

linker histone and its gene have been designated “histone H1” or Hho1p. It was

shown that its gene (HHO1) is expressed as a poly-A+ RNA but is not

essential [119, 120]. Surprisingly, gene deletion was not detected to affect cell

growth, mating or viability. However, it was found that deletion of the

HHO1 gene significantly alters the expression of

Before the yeast linker histone was discovered, it was hypothesized that any linker histone-like protein in yeast may have two globular domains [124]. This was later proven correct, defying the yeast Hho1 as remarkable and unique among eukaryotic linker histones. The hypothesis for the existence of two globular domains was confirmed, as well as the fact that these domains both have considerable similarity to the winged-helix motifs in other eukaryotic linker histones [119, 125, 126]. It was shown that Hho1p interacts in vitro with four-way junction DNA molecules through its two globular domains, implying the possibility of simultaneous binding of two adjacent nucleosomes [127]. Inconsequent data has shown that Hho1p is involved in the activity of RNA polymerases and is essential for regulating their processivity [128]. The functional interaction of Hho1p with core histone H4 and its involvement in establishing transcriptionally silent chromatin was also shown [129].

With the increasing research, the structural and functional importance of the yeast Hho1 is steadily elucidated. Despite not being vital for survival, cell viability and reproduction, Hho1 demonstrates intricate structural and functional importance inside the yeast cell.

Some authors have shown that S. cerevisiae linker histone Hho1p represses recombination at the rDNA without affecting RNA polymerase II (Pol II) gene silencing. However, the cells lacking histone H1 do not exhibit a premature-ageing phenotype nor accumulate the rDNA recombination intermediates and products found in cells lacking Sir2p. It was proposed that histone H1 acts independently of Sir2 to prevent recombination events at the rDNA that, if allowed to occur, would contribute to genomic instability [130]. These results indicated that the linker histone and ageing connection should be searched elsewhere.

In a set of consecutive experiments in our laboratory, the gene HHO1 for this histone has been knocked out, allowing us to obtain a linker histone-free strain [14]. These cells were used as a model for studying chromatin during cellular ageing. Our results showed slower growth and a substantial delay in the logarithmic phase in hho1p delta mutant cells. However, these cells showed increased survival throughout the cultivation period [46, 131]. When examined, the overall chromatin organization of these mutant cells showed the existence of longer chromatin loops in comparison with the loops of the wild type, as well as distorted higher-order chromatin organization accompanying the ageing process. Our results underline the importance of the linker histones and the higher-order chromatin structures in cellular ageing [131].

The production of free oxygen species, for example, during exposure to ultraviolet (UV) rays, is considered one of the main reasons for ageing. The cells under UV rays, for a prolonged time, proceed through a process of photoaging that has been proven to be damaging to the skin [132]. Invisible to the naked eye, this light causes severe DNA damage, inhibiting DNA replication and transcription and promoting genome instability. The three types of UV rays—UVA (320–400 nm), UVB (290–320 nm), and UVC (190–280 nm) produce photo lesions, leading to incorrectly incorporated nucleotides in the newly synthesized DNA [133]. UVB radiation causes DNA damage by forming dimeric photoproducts like cyclobutane pyrimidine dimers and pyrimidine (6-4) pyrimidone photoproducts [134]. UVB is the leading cause of sunburn and most types of skin cancer. In contrast, UVA is the main initiator of oxidative damage and more permanent ageing features like wrinkles and some types of skin cancer [135].

The advantage of using Saccharomyces cerevisiae as a model organism lies in its status as a single-celled entity, which allows researchers to differentiate between replicative and chronological ageing. This distinction provides an ideal framework for studying the relationship between these two types of ageing under various stress conditions. Recent investigations have focused on the molecular mechanisms underlying the cellular response to UVA/B light during chronological ageing in chromatin mutant yeast cells. Specifically, researchers compared the survival abilities of three distinct chromatin mutant strains: one with a knockout of the linker histone gene, another with a point mutation in the Actin-Related Protein 4 (ARP4) gene, and a double mutant combining both genetic alterations [136]. These results revealed that altered chromatin organization in yeast lacking the linker histone significantly impacted the expression of critical genes such as CDC28, RAD9, and ATG18, which are integral to DNA repair and autophagy processes. Observing how the otherwise enigmatic linker histone Hho1p influences ageing processes is intriguing, particularly under stress conditions. The findings indicated that yeast cells devoid of linker histones exhibited increased viability after exposure to low doses of UVA/B irradiation.

Given that UVA/B light exposure is a well-known cause of DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs), this outcome suggests a potential adaptive advantage [46, 136]. Cells typically utilize homologous recombination and non-homologous end-joining pathways to repair DSBs. Interestingly, evidence suggests that yeast linker histones act as homologous recombination inhibitors. Therefore, the absence of linker histones may facilitate a more rapid and efficient repair of DSBs via homologous recombination, ultimately enhancing cell viability in linker histone mutants following UVA/B exposure [123]. Considering the critical role of linker histone Hho1p in establishing and maintaining chromatin structure [14], it becomes evident that global chromatin reorganization occurs during ageing. This underscores the importance of proper chromatin organization for appropriate cellular ageing, suggesting that disruptions in this organization could contribute to age-related decline and disease. Thus, understanding the dynamics of linker histones and their influence on chromatin structure may provide valuable insights into the mechanisms of ageing and potential therapeutic targets for age-related conditions [131].

Ageing is a complex and naturally occurring process influenced by many factors and conditions. While ageing is inevitable, certain factors can be manipulated to facilitate or slow its progression. Understanding the influence of chromatin on ageing presents a promising opportunity to mitigate some of the features associated with cellular ageing. In this context, linker histones, mainly histone H1, emerge as valuable targets for diagnosing and potentially inhibiting age-related features. Recent findings underscore the multifaceted roles of linker histones in chromatin dynamics, suggesting that they are not merely structural components but also active participants in regulating gene expression and maintaining genome stability. The connection between histone dynamics, ageing, and cancer development further emphasizes their significance, indicating that alterations in linker histones could contribute to the onset of age-related diseases and malignancies. Moreover, exploring histone H1 variants across different cell types and organisms highlights their potential as therapeutic targets. By targeting these variants, it may be possible to develop interventions that address the underlying mechanisms of ageing and improve cellular function.

In conclusion, advancing our understanding of linker histones and their regulatory roles in chromatin biology could pave the way for innovative strategies to combat ageing and enhance genome stability, ultimately contributing to healthier ageing and improved outcomes in age-related diseases [137].

Conceptualization, GM and MG; investigation, BV, PI, MG, GM; resources, GM, PI, BV, MG; original draft preparation – GM, PI, BV, MG; writing—review and editing, GM and MG; visualization, GM, MG; supervision, GM; project administration, MG; funding acquisition, MG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by BULGARIAN SCIENCE FUND, Grant Number: KP 06-N-71/4.

Given her role as the Guest Editor, Milena Georgieva had no involvement in the peer-review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Amancio Carnero Moya. The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.