1 Department of Fundamental and Applied Aspects of Obesity, National Medical Research Center for Therapy and Preventive Medicine, 101990 Moscow, Russia

2 Department of Therapy and Preventive Medicine, A.I. Evdokimov Moscow State University of Medicine and Dentistry, 127473 Moscow, Russia

3 Centre for Strategic Planning and Management of Biomedical Health Risks, Federal Medical Biological Agency, 123182 Moscow, Russia

4 Coordinating Center for Fundamental Research, National Medical Research Center for Therapy and Preventive Medicine, 101990 Moscow, Russia

Abstract

To date, an increasing body of evidence supports the potential role of activated platelets in the pathogenesis of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). This is likely due to their ability to secrete biologically active substances that regulate liver regeneration processes, ensure hemostasis, and participate in the immune response. Additionally, several studies have demonstrated the efficacy of antiplatelet agents in reducing inflammation, the severity of liver fibrosis, and the progression of fibrosis in non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Since NAFLD is not an independent indication for antiplatelet therapy, the primary evidence regarding their efficacy in NAFLD has been derived from studies using animal models of NAFLD or in patients with concomitant cardiovascular diseases. This narrative review will discuss the main functions of platelets, their unique interactions with liver cells, and the outcomes of these interactions, as well as the results of studies evaluating the efficacy and safety of antiplatelet therapy in patients with NAFLD.

Keywords

- non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

- non-alcoholic steatohepatitis

- Kupffer cells

- liver sinusoid epithelial cells

- platelets

- acetylsalicylic acid

- antiplatelet agents

Liver diseases are among the most pressing problems for healthcare workers. They account for over two million deaths worldwide: nearly 1 in 25 deaths are caused by them [1]. Complications of cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) lead to death. The most common causes of the former are alcoholic liver disease, viral hepatitis, and non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), also known as metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) in the new nomenclature [2, 3]. The worldwide prevalence of NAFLD has increased greatly over the past few years, reaching up to 40% in Western countries and about 30% in Asian countries [4, 5]. According to the literature, the prevalence of NAFLD in Africa is estimated to be 13.5%, however, it should be noted that the information concerning the incidence and prevalence of NAFLD in Africa is very limited [6]. Based on the results of the meta-analysis by Rojas et al. [6] the average prevalence of NAFLD in Latin America is around 24% but may increase up to 68% in high-risk groups, such as patients with obesity and type 2 diabetes. The discrepancies in NAFLD prevalence among different regions are thought to be associated with various genetic and sociodemographic determinants, prevalence of obesity, especially visceral adiposity, and type 2 diabetes [7]. Liver transplantation is the only radical treatment for end-stage cirrhosis. It is a high-tech and expensive intervention that increases the global burden of liver disease. Also, with the current rate of transplantation and the increasing incidence of both alcoholic and non-alcoholic liver damage, there is a significant shortage of donor organs: only 10% of the need for transplantation is covered worldwide [8]. According to Cotter and Charlton et al. [9], NAFLD is the second most common etiological factor in cirrhosis leading to transplantation.

At the same time, the share of NAFLD in the structure of HCC causes is

increasing: it constitutes the fourth leading cause of cancer mortality worldwide

[2, 10]. Given the increasing prevalence of metabolic syndrome and obesity, NAFLD

may become the leading cause of HCC, and the disease usually develops in elderly

and comorbid patients, which significantly reduces treatment options and worsens

the life prognosis for these patients [11]. It should be noted that in NAFLD,

unlike other liver diseases, HCC can develop at the stage of non-alcoholic

steatohepatitis (NASH), even in the absence of cirrhosis [12]. For instance, the

annual incidence of HCC was 2.8 per 1000 person-years for NAFLD patients with

Fibrosis-4 Index (FIB-4)

To date, there is no effective etiotropic therapy for NAFLD, and the development of this disease is closely associated with many other pathological conditions that affect the life expectancy in patients. Among the most common comorbid NAFLD diseases are cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus, cholelithiasis, chronic kidney disease, obstructive sleep apnea syndrome, osteoporosis, etc. [15]. Therefore, NAFLD contributes to mortality rates from cardiovascular diseases (which are the leading cause of death worldwide) rather than mortality rates from liver diseases alone. Given this feature, the importance of NAFLD for the healthcare system can hardly be overestimated.

Taking into account all of the above, it is extremely important and compulsory to study the pathogenesis of NAFLD, which will help us develop more effective treatment methods, recognize new targets for therapy, identify accurate diagnostic and prognostic markers of the disease, and also establish factors that determine the relationship between NAFLD and other chronic non-communicable diseases (CNCD). Currently, the idea of multifactorial pathogenesis of NAFLD prevails, which includes various simultaneously occurring processes, such as insulin resistance (IR), lipotoxicity, inflammation, imbalance of cytokines and adipokines, activation of innate immunity, disrupted diversity of the intestinal microbiota, as well as exposure to environmental and genetic factors. Along with this, NAFLD is commonly perceived as a prothrombotic condition accompanied by platelet activation. Accordingly, the researchers began to focus on studying the role of activated platelets in the pathogenesis of NAFLD. In particular, a correlation between the concentration of activated platelets in the liver sinusoids and the severity of hepatic steatosis and steatohepatitis has been described [16]. Among other things, the role of platelets in the pathogenesis of NAFLD may be due to their impact on the activation of hepatic stellate cells. The latter are responsible for the increased production of extracellular matrix components, thereby participating in the development and progression of liver fibrosis. This hypothesis is supported by the fact that acetylsalicylic acid, as an antiplatelet medication, suppresses platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) signaling and slows the rate of fibrosis progression [17].

In this review, we will discuss the causes and mechanisms of liver tissue infiltration by activated platelets, along with their role in the genesis of NAFLD.

Platelets are anucleate cells formed from megakaryocytes under the influence of various cytokines and growth factors, the foremost of which is thrombopoietin (TPO) [18]. TPO is a glycoprotein produced by hepatocytes at a constant rate, while platelets play a key role in regulating its levels by binding to the cluster of differentiation (CD)110 receptor on circulating platelets [19] and removing TPO from circulation [20]. Platelets are habitually perceived from the standpoint of their participation in hemostasis. However, we observe a steep increase in the number of recent publications dedicated to their role in systemic inflammatory responses, as well as the influence of antiplatelet drugs on the course of inflammatory and oncological diseases [21, 22]. In addition, platelets secrete several growth factors, including PDGF and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), which are involved in liver regeneration [23].

The participation of platelets in hemostasis is provided by the following functions [24]:

(1) Angiotrophic function (under physiological conditions, about 15% of circulating platelets are spent daily to carry out this function providing endothelial cells with nutrients);

(2) The ability to maintain spasms of injured blood vessels through the secretion of vasoactive substances (adrenaline, serotonin);

(3) The activation of secondary coagulation hemostasis due to (a) platelet factor 3 (a component of the platelet membrane playing the role of a phospholipid matrix on which coagulation hemostasis reactions occur) and (b) the release of other procoagulants in the course of degranulation;

(4) The capability to clog an injured vessel with a primary platelet thrombus formed due to their functions of adhesion and aggregation;

(5) Reparative function via the release of a growth factor that causes migration of fibroblasts, macrophages, and smooth muscle cells to the site of injury;

(6) Retraction of a blood clot with the participation of contractile proteins.

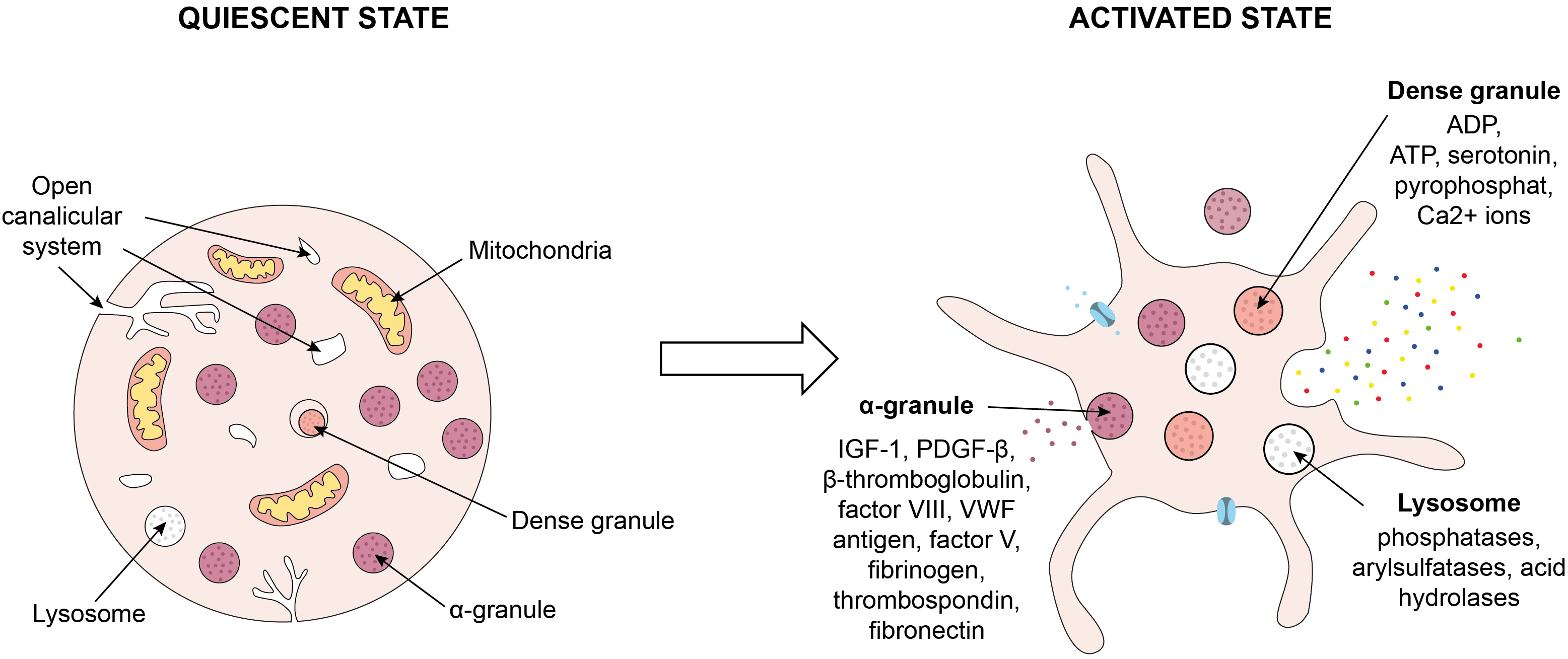

The process of platelet aggregation with the formation of aggregates is preceded

by their activation involving a change in their shape from discoid to spherical

and the formation of pseudopodia [25]. Platelets form aggregates and release the

contents of their granules in such a transformed state. Granules are

platelet-specific organelles classified into

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Process of platelet activation. Platelet activation involves a

change in their shape from discoid to spherical and the formation of pseudopodia.

Platelets form aggregates and release the contents of their granules in such a

transformed state. ADP, adenosine diphosphate; ATP, adenosine triphosphate;

IGF-1, insulin-like growth factor 1; PDGF-

For complete adhesion of platelets to the site of injury, the following conditions need to be met:

- contact with the main stimulator of adhesion (subendothelial collagen) in the presence of a plasma cofactor (calcium ions);

- platelet activation;

- synthesis of adhesive proteins (VWF, etc.) by endothelial cells;

- expression of VWF receptors, glycoproteins Ib (GPIb), on the platelet membrane.

Vascular injury results in exposure of collagen and VWF in the vessel wall. Circulating platelets adhere and form a monolayer of activated platelets on a collagen matrix, which results in the release of ADP and thromboxane A2 (TXA2) from the adherent platelets. The secretion of ADP and TXA2 contributes to a change in the shape of platelets and their increased activation. Thrombin, the final product of the coagulation cascade, is the most potent platelet activator. During the perpetuation phase of thrombus formation, platelet contacts promote growth and stabilization of the platelet plug [27].

The interaction between platelets and the liver is bidirectional. On the one hand, the liver participates in platelet formation. On the other hand, platelets ensure liver homeostasis and the integrity of blood vessels in the liver, participate in the regulation of immune control, and safeguard the vital activity of liver cells by being a source of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), HGF and PDGF, and chemokines (C-X-C motif) ligand 1 (CXCL1, CXCL4, CXCL5, and CXCL7). In addition, acute phase proteins, blood clotting HGFs, and lipoproteins, all synthesized in the liver, are involved in platelet activation [28].

It was previously thought that platelet mobility was determined by blood flow. However, Gaertner et al. [29] demonstrated that activated platelets were able to move against the blood flow. At the same time, the migration of leukocytes did not affect their mobility [29, 30]. The platelets’ ability to move against blood flow is largely due to their unique adhesive properties and cytoskeletal changes, which differ from the rolling and adhesion behavior of white blood cells. Platelets use glycoproteins like GPIb and integrins to adhere to endothelial surfaces [31]. Once attached, platelets undergo cytoskeletal changes, allowing them to spread and “crawl” along the endothelium. This movement is mediated by actin and myosin filaments inside the platelets, which create contractile forces and help them maneuver [32]. In regions of high shear stress (like arterioles), platelets adhere to the endothelium through interactions with VWF bound to the endothelial surface. VWF acts as a bridge between platelet receptors (like GPIb) and the endothelial wall, helping platelets stay attached even against strong blood flow [31].

The ability of platelets to actively move may be important in infectious diseases. Once platelets arrive at sites of bacterial infection, they begin to migrate, allowing the collection and clustering of bacteria and the recruitment and activation of professional phagocytes. The alignment of these two functions places platelets in a central role in innate immune responses and identifies them as a potential target for suppressing inflammatory damage of tissues in certain clinical scenarios [29, 33]. In addition, platelet migration is required to clear the microenvironment from fibrin depositions. After moving fibrin depositions from coated surfaces, platelets transport the scavenged material into the open canalicular system (OCS), which represents a continuous invagination of the outer plasma membrane. Thus, platelets may function as mechano-scavengers owing to their ability to apply pulling forces and to scavenge all the objects and structures that cannot resist these forces [34].

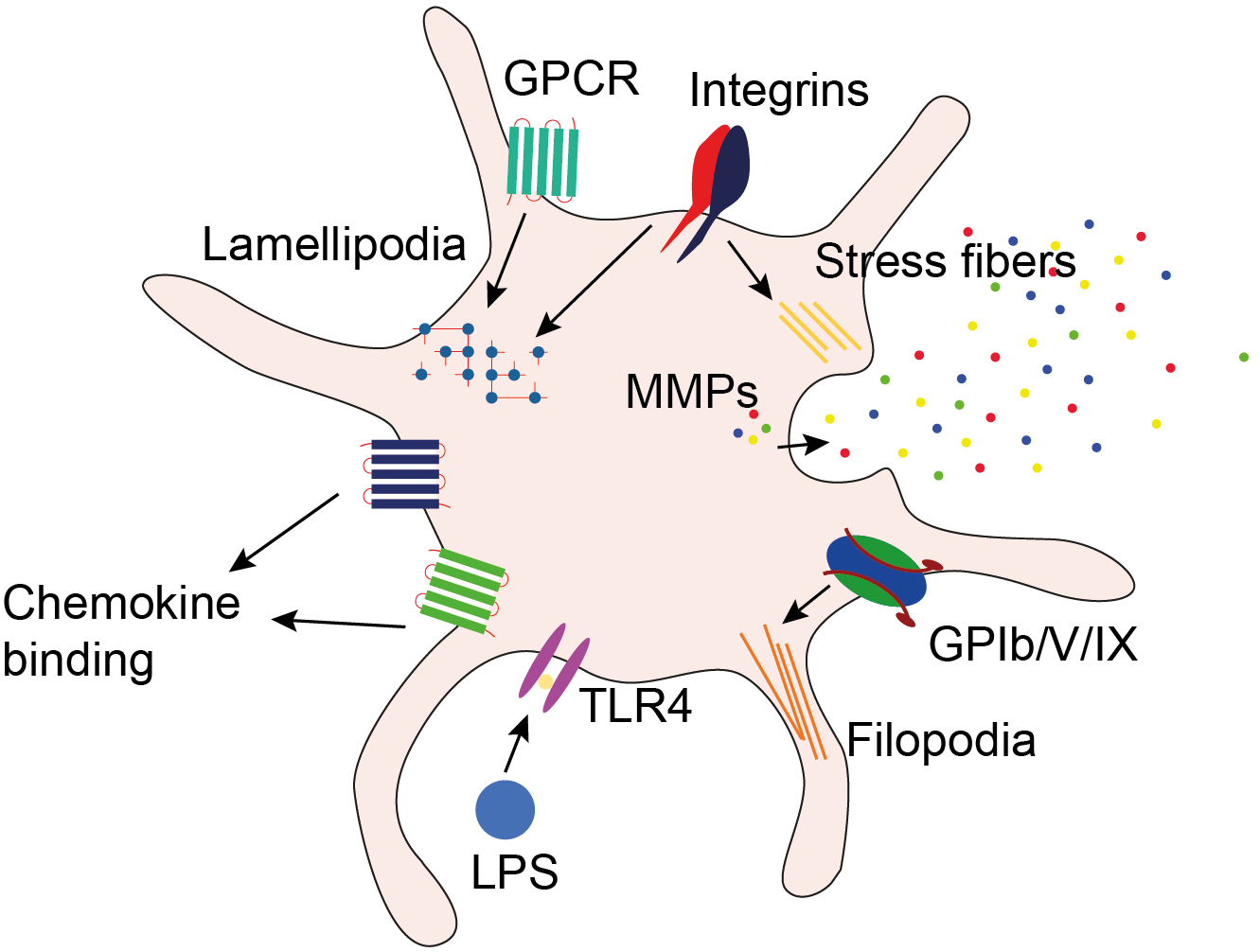

The ability of platelets to migrate may be explained by the following features of these cells: platelets express receptors for adhesive proteins and chemokines, contain and secrete matrix metalloproteinases required for extracellular matrix degradation, and have the cytoskeletal and enzymatic systems required for cell migration (Fig. 2) [35].

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Features of platelets explaining their ability to migrate. Platelets express receptors for adhesive proteins and chemokines, contain and secrete matrix metalloproteinases required for extracellular matrix degradation, and have the cytoskeletal and enzymatic systems required for cell migration. GPCR, G-protein-coupled receptor; GPIb/V/IX, glycoprotein Ib/V/IX; LPS, lipopolysaccharide; MMPs, matrix metalloproteinases; TLR4, toll-like receptor 4.

To examine the mechanisms of platelet migration into the liver microvasculature,

Jenne et al. [36] used antibodies to the leucocyte adhesion

molecule, CD-18, and showed that blockade of CD-18 did not affect the migration

of neutrophils into the liver microvasculature of mice after administration of

lipopolysaccharide (LPS). However, blockade of CD-18 in LPS-treated mice

significantly limited the entry of platelets into the liver, their adhesion to

neutrophils or endothelial cells, and their formation of aggregates. These

results are of particular interest because platelets are not known to express

CD-18. The latter molecule is expressed on the membrane of neutrophils [37] and

Kupffer cells [38], and platelets express several ligands for

At the same time, the authors of the above-mentioned study found no evidence for a role of platelet-derived GPIIb/IIIa in NASH, suggesting that platelet activation and adhesion are important, whereas platelet aggregation is dispensable.

In their study, Mende et al. [39] studied the effect of blockade of the main platelet receptor for thrombin, protease-activated receptor 4 (PAR4), on platelet migration to the liver and damage to the liver microvasculature under conditions of ischemia/reperfusion in C57BL/6 mice. According to the results of that study, the use of the PAR4 antagonist (tcY-NH2) was accompanied by a reduction in the migration of platelets and CD4 T lymphocytes to the liver, in the extent of damage to the liver microvasculature, and also in apoptosis and necrosis of hepatocytes induced by ischemia/reperfusion. At the same time, the blockade of PAR4 did not disrupt hemostasis and did not reduce the ability of the liver to regenerate.

Hepatocytes make up 70% of liver cells, and the remaining cells consist of bile epithelial cells, Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs), Kupffer cells, lymphocytes, and hepatic stellate cells. In this section, we will discuss the main effects of interactions between platelets and various types of liver cells.

Liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) have a unique phenotype because,

unlike other endothelial cells, they do not contain Weibel–Palade bodies in a

mature differentiated state and therefore lack the ability to express P-selectin

and VWF in small quantities even under inflammatory conditions. This

circumstance, along with the low shear rate inside the liver sinusoids, creates

unique conditions for the adhesion of platelets and leukocytes [40]. ICAM-1

(Intercellular Adhesion Molecule-1) and VCAM-1 (Vascular Cell Adhesion

Molecule-1) can be upregulated in response to inflammatory signals. Platelet

integrins (such as

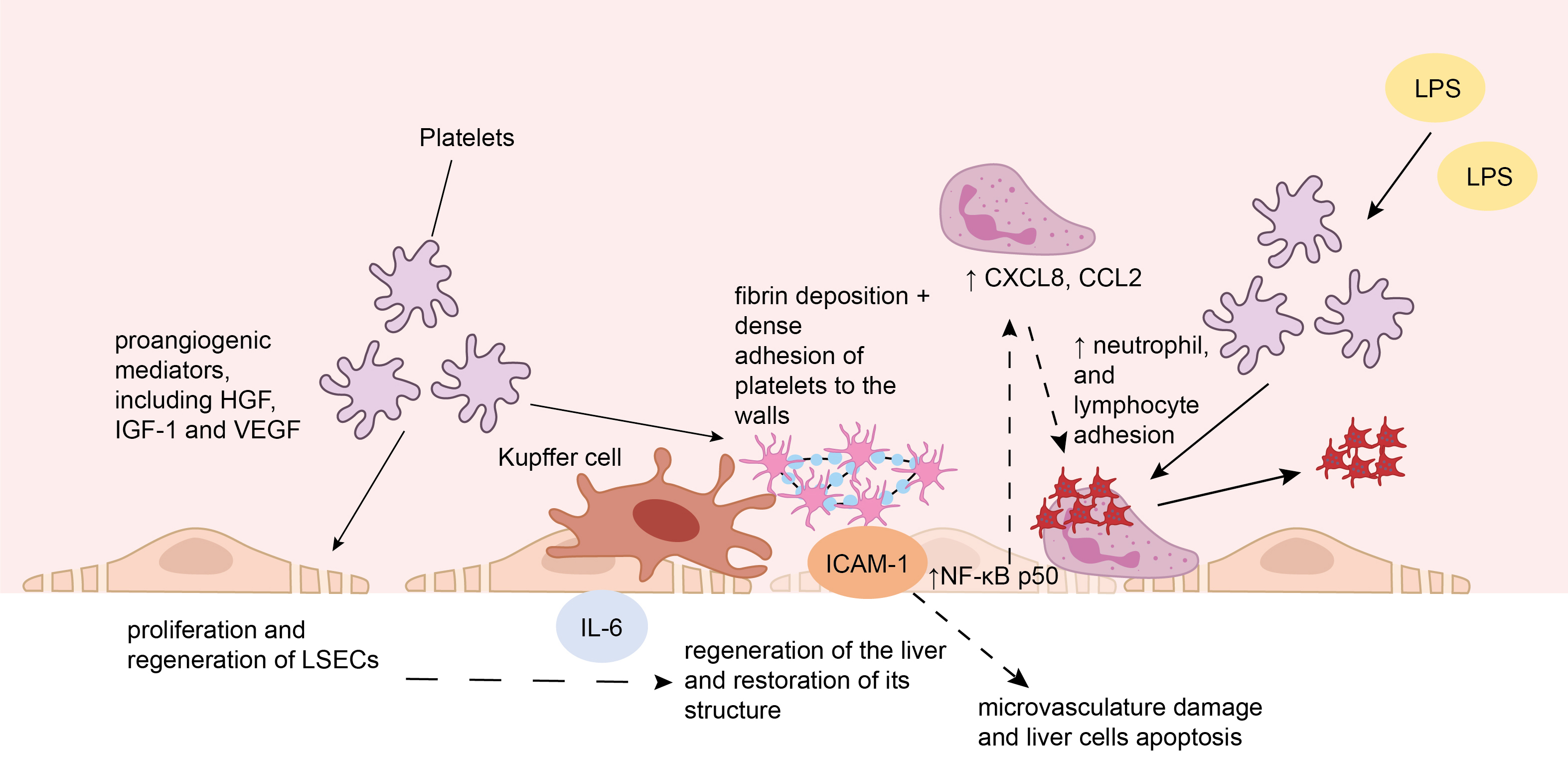

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

The interaction of platelets with liver sinusoidal endothelial

cells. (1) Platelets entering the liver sinusoids after injury secrete

proangiogenic mediators, including hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), insulin-like

growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which

promote the proliferation and regeneration of liver sinusoidal endothelial cells

(LSECs). (2) The interaction of platelets with LSECs triggers the formation of

interleukin 6 (IL-6), which stimulates the division of hepatocytes. (3) Under

conditions of ischemia/reperfusion, fibrin deposition on the endothelium occurs

which is followed by dense adhesion of platelets to the walls of microvasculature

vessels. The latter is triggered by the binding of fibrinogen to intercellular

adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1) on the surface of LSECs. These processes cause

damage to the microvasculature of the liver and apoptosis of liver cells. (4)

Binding of platelets to LSECs results in activation of nuclear factor kappa B

(NF-

Platelets entering the liver sinusoids after injury under conditions of ischemia/reperfusion secrete proangiogenic mediators, including HGF, IGF-1, and VEGF, which promote the proliferation and regeneration of LSECs, thereby contributing to the regeneration of the liver and restoration of its structure [46]. The interaction of platelets with LSECs during liver regeneration after partial hepatectomy triggers the formation of interleukin 6 (IL-6), which is the main cytokine that stimulates the division of liver cells [47].

At the same time, platelets located in the liver sinusoids can trigger the inflammatory process, thereby playing a key role in the pathogenesis of liver damage under conditions of ischemia/reperfusion, which is the cause of the development of liver failure after liver transplantation and extensive surgical interventions. Under conditions of ischemia/reperfusion, fibrin deposition occurs on the endothelium of liver blood vessels, which in turn leads to a significant increase in the dense adhesion of platelets to the walls of microvasculature vessels. Simultaneously, the number of leukocytes adhering to the walls of the postsinusoidal veins increases, as well as the activity of Alanine transaminase (ALT), Aspartate transaminase (AST), and caspase-3.

In their in vivo study on C57BL/6 mice, which were distributed among three groups (wild-type mice, mice with the deletion of the gene of intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and wild-type mice treated with anti-fibrinogen antibodies), Khandoga et al. [48] demonstrated that the cause of damage to the microvasculature of the liver and apoptosis of liver cells in the early phase of damage under conditions of ischemia/reperfusion was the adhesion of platelets to the wall of the microvasculature vessels, triggered by the binding of fibrinogen to ICAM-1 on the surface of the liver microvasculature endothelium after an episode of ischemia.

In order to further study the mechanisms of ischemia/reperfusion damage to the liver, van Golen et al. [49] attempted to determine whether platelets were activated and degranulated during the acute phase of liver ischemia/reperfusion. In their study conducted on male C57BL/6J mice, they showed that platelets adhered more actively to sinusoids in the post-ischemic liver compared with the liver not exposed to ischemia/reperfusion, and formed aggregates immediately after ischemia. However, in the post-ischemic liver, platelets did not become activated and did not degranulate [49].

Similarly, the binding of platelets to the LSECs increased when lipopolysaccharide (LPS) was administered intravenously to mice at a dose of 1 mg/kg of body weight for 4 hours [36]. Interestingly, the authors of that study showed that platelets bound not only with LSECs, but also with Kupffer cells and neutrophils, and noted that the number of platelets in the peripheral blood of mice after LPS administration decreased significantly. Jenne et al. [36] revealed that in mice injected with LPS, platelets interacted primarily with neutrophils already attached to the walls of the liver sinusoids. At the same time, a much smaller number of platelets were binding directly with LSECs, and virtually no interactions were observed between platelets adhered to the walls of the liver microvasculature vessels and circulating neutrophils. On the surface of endothelial cells of the liver microvasculature or neutrophils adhered to them, platelets formed unstable aggregates, which in a short while were detached from the underlying structure and entered the bloodstream. On the contrary, in the liver of mice that did not receive LPS, the number of neutrophils adhering to the walls of the sinusoids was substantially lower and they remained free of platelets. Under such conditions, platelets did not form aggregates on the surface of neutrophils. Additionally, Jenne et al. [36] demonstrated that similar changes after LPS administration were observed in other organs and tissues — e.g., in the brain (where most of the described intercellular interactions occurred in postcapillary venules) and in the microvasculature of skeletal muscles.

Lalor et al. [40] demonstrated that platelet adhesion to LSECs occurred

due to platelet receptors, in particular the integrins GpIb,

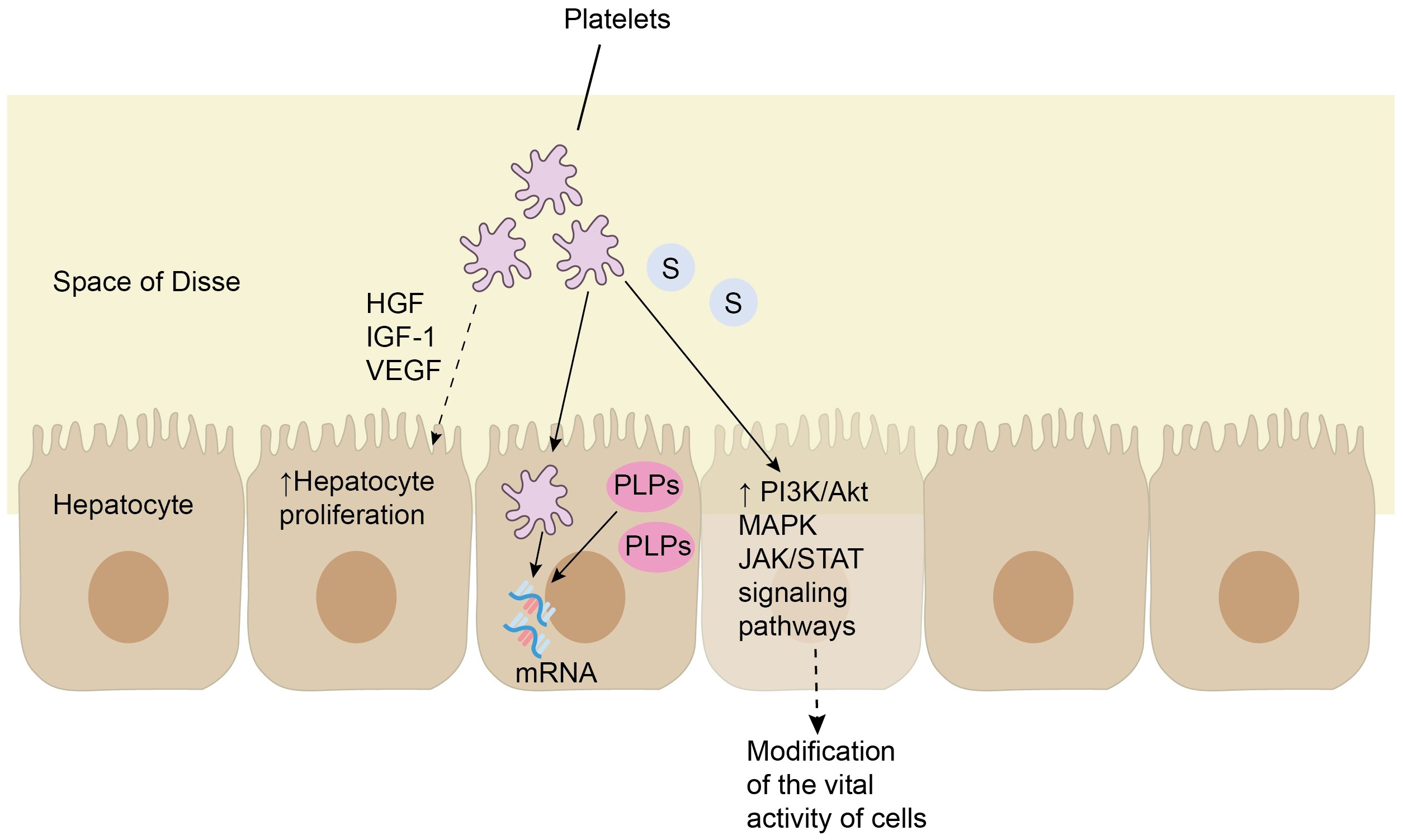

From the liver sinusoids, platelets can migrate into the perisinusoidal space (space of Disse), where they come into direct contact with hepatocytes. The result of this interaction is the release of soluble mediators by platelets, in particular HGF, IGF-1, and VEGF, which stimulate the proliferation of hepatocytes [54].

Stolz et al. [55] in their study showed that within 30 minutes after partial hemihepatectomy in rats, the concentration of HGF in the blood plasma increased greatly simultaneously with an increase in the expression of HGF receptors by hepatocytes. At the same time, the HGF reserves contained in the liver were completely depleted within 3 hours after the intervention [56].

While HGF-c-Met signaling is often sufficient for hepatocyte proliferation, direct uptake of platelets and platelet-like particles (PLPs) by hepatocytes (i.e., through receptor-mediated endocytosis [57] or phagocytic processes [58]) can further enhance proliferation, providing additional regenerative cues. In vitro studies involving co-culture of hepatocytes, platelets, and platelet-like particles (PLPs) discovered that after 1 hour of co-culture, platelets and PLPs could be visualized in the perinuclear region of hepatocytes. Moreover, after some time of co-cultivation, the glow from the green fluorescent protein, which labeled messenger RNA (mRNA) contained in PLPs, was detected in various structures of the hepatocyte cytoskeleton. This supported the idea that platelets are capable of stimulating hepatocyte proliferation via mechanisms activated by the transfer of mRNA from PLPs after the uptake of platelets and PLPs by hepatocytes [59].

The role of serotonin in liver regeneration currently is still considered controversial. A study by Takahashi et al. [60] suggested that serotonin released by platelets was a necessary mediator for liver regeneration processes after injury. The effects of serotonin (in general, including hepatocytes) are implemented through its binding to specific membrane receptors, most of which are G protein-coupled receptors. As a result, the Phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K)/Protein kinase B alpha (Akt), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and Janus kinase (JAK)/signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling pathways are activated, which can modify the vital activity of cells. The interaction of platelets with hepatocytes is presented on Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

The interaction of platelets with hepatocytes. From the liver sinusoids, platelets can migrate into the space of Disse, where they come into direct contact with hepatocytes. As a result, platelets release soluble mediators, in particular hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which stimulate the proliferation of hepatocytes. In turn, hepatocytes are capable of uptaking platelets and platelet-like particles (PLPs) containing messenger RNA (mRNA), which may also stimulate their proliferation. Finally, serotonin (S) released by platelets is capable to activate the phosphoinositide 3-kinases (PI3K)/protein kinase B alpha (Akt), mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) and Janus kinase (JAK)/ signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) signaling pathways via binding to specific membrane receptors of hepatocytes, most of which are G protein-coupled receptors, and thus modify the vital activity of liver cells.

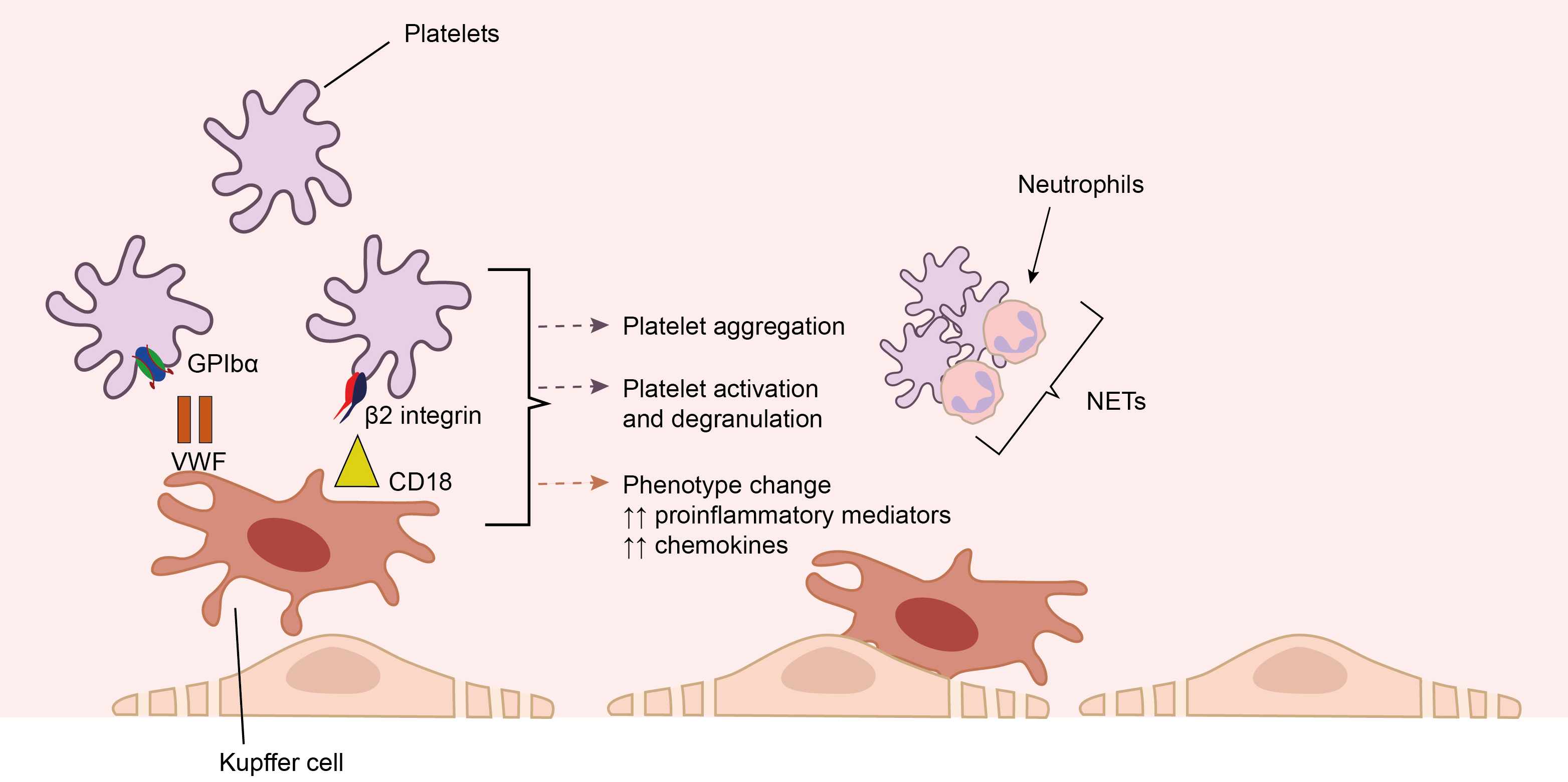

Platelets activated upon contact with inflamed liver sinusoidal endothelial cells or in response to inflammatory signals release soluble mediators that facilitate the recruitment of neutrophils and monocytes to inflamed liver sinusoids to provide immunosurveillance. Migration of platelets and their attachment to LSECs is ensured by GPIb through interaction with VWF expressed on Kupffer cells [28, 61, 62]. After their attachment to Kupffer cells, platelets serve as a platform for the recruitment and attachment of neutrophils to the perisinusoidal space, contributing to the subsequent formation of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) [29]. An increase in the number of platelet-leukocyte aggregates can have both favorable and adverse effects depending on the severity of liver disease. In a model of ischemia-reperfusion injury and partial hepatectomy, migration of activated platelets promoted hepatocyte proliferation by increasing serotonin concentrations [63]. At the same time, in models with cholestatic damage, e.g., bile duct ligation (BDL) model, platelet accumulation mediated by P-selectin contributed to the sequestration of leukocytes and the development of additional damage to hepatocytes [64]. Thus, NETs formed by platelet-neutrophil interactions may have beneficial effects in moderate liver damage scenarios but can exacerbate injury when the liver damage is more severe or chronic. The interaction of platelets with Kupffer cells is presented on Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

The interaction of platelets with Kupffer cells. Migration of

platelets and their attachment to liver sinusoidal endothelial cells (LSECs) may

be ensured by glycoprotein Ib (GPIb) through interaction with VWF, as well as by

Data from animal studies and in vitro studies indicated that with the development of inflammation or after partial resection of the liver, platelets accumulated in the liver sinusoids, later migrating into the space of Disse, while some platelets were captured by hepatocytes. Then, probably, the release of mediators contained in platelets occurs: serotonin, IGF-1, and HGF, affecting the proliferation of hepatocytes or endothelium. Besides, the direct interaction of platelets with endothelial cells leads to the release of IL-6 and VEGF, thereby promoting regeneration [65].

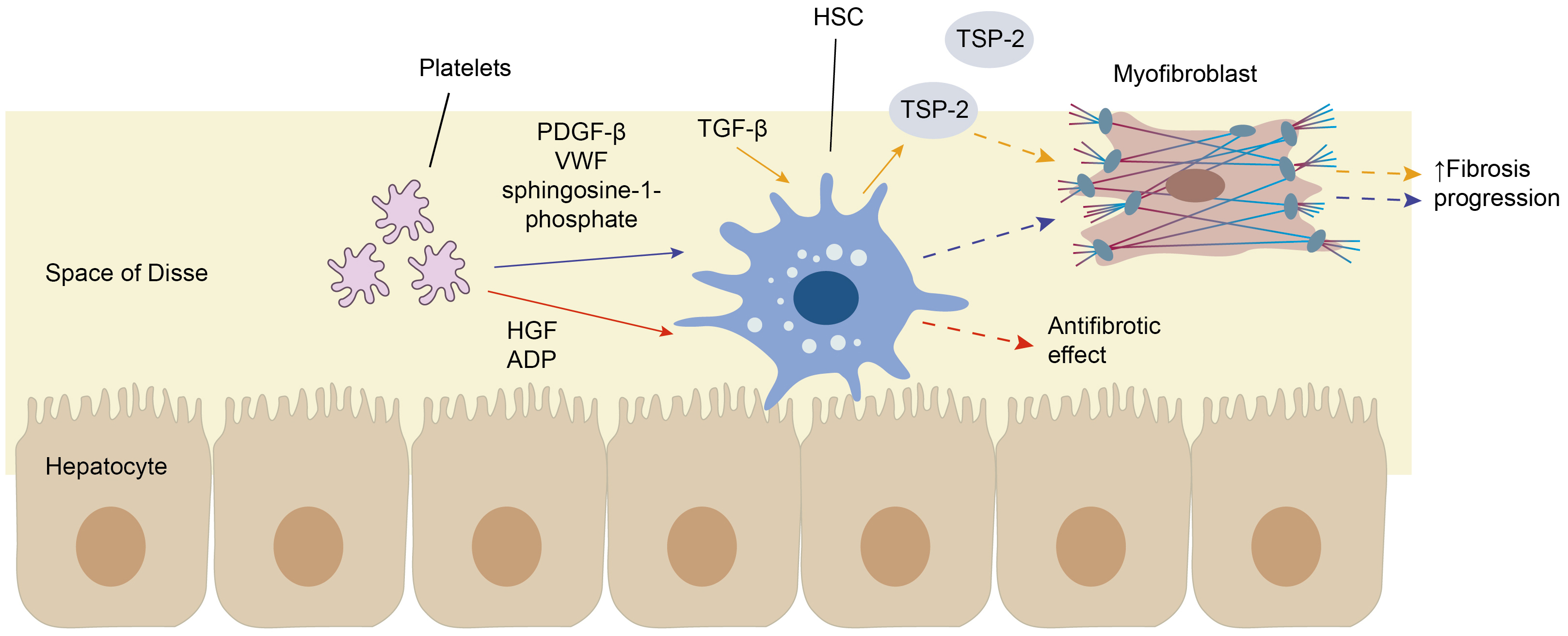

Platelets can also interact with hepatic stellate cells (Ito cells) through

molecules that exert both pro- and anti-fibrotic effects [23]. The net effect of

platelet interaction with hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) depends on the balance

between pro-fibrotic and anti-fibrotic mediators. It is influenced by a

combination of factors, including the ratio between anti- and pro-fibrotic

mediators, their relative expression levels, and context-specific regulatory

signals in the liver microenvironment [66]. Adenine nucleotides and hepatocyte

growth factor, contained within platelet granules, exhibit antifibrotic effects

[67]. These effects are supported by a reduction in liver fibrosis observed

during treatment with platelet-rich plasma (PRP) [68]. The profibrotic effects of

activated platelets can be mediated through signaling pathways such as

TGF-

The content of platelet

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-Seq) analysis identified HSCs as the primary

cell cluster expressing THBS2. The level of THBS2 expression in

Ito cells from patients with NAFLD and developed fibrosis was greater than in

healthy individuals or patients with NAFLD without fibrosis. In situ

hybridization analysis of liver tissue from patients with severe fibrosis

demonstrated high THBS2 expression in hepatic stellate cells at the

boundaries of collagen fiber accumulation. Knockout of the THBS2 gene

substantially reduced collagen synthesis by the human hepatic stellate cell line

(LX-2), which was derived from HSCs. Administration of TGF-

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

The interaction of platelets with hepatic stellate cells.

Platelets can interact with hepatic stellate cells (HSCs) through molecules that

exert both pro- and anti-fibrotic effects. For instance, adenosine diphosphate

(ADP) and hepatocyte growth factor (HGF), contained within platelet granules,

exhibit antifibrotic effects (red arrows). The profibrotic effects of activated

platelets can be mediated through transforming growth factor-

In a study by Alkhouri et al. [80] conducted on patients with NAFLD, an

increase in mean platelet volume (MPV) was detected, a marker of platelet

activation and a confirmed cardiovascular risk factor. Larger platelets vs.

smaller platelets were characterized by higher activity of enzymes, synthesis of

larger amounts of thromboxane A2, and higher likelihood of aggregation and blood

clot formation. Also, a correlation was revealed between the MPV and the

histological features of NASH (p

In 2023, Karaoğullarindan et al. [82] published a study assessing

the relationship between MPV and histological changes in liver tissue. The

research included 124 patients with histologically confirmed NAFLD, 108 healthy

individuals without liver disease, and 156 patients with chronic viral

hepatitides B and C. The study established that the MPV value in patients with

NAFLD was significantly higher, while the number of platelets, on the contrary,

was lower than in healthy study subjects. The authors concluded that a higher MPV

may have indicated that a patient had more severe fibrotic and

necroinflammation-related changes in the liver. However, Madan and Garg [83],

commenting on that study in their article, pointed out that the conclusions by

Karaoğullarindan et al. [82] were somewhat unfounded. In particular,

Madan and Garg [83] argued that in conditions of chronic inflammation, the

response on the part of platelet cell count can develop in two ways. In one

scenario, the inflammatory response produces larger platelets that are more

active, but the total number of platelets decreases. On the contrary, in another

scenario, the number of platelets increases, but their mean volume decreases. For

example, Kim et al. [84] demonstrated that in patients with rheumatoid

arthritis, MPV depended on disease activity. e.g., in patients with an active

course of rheumatoid arthritis (defined by elevated C-reactive protein levels),

the MPV was reduced and averaged

9.80

Moreover, according to Ozhan et al. [85], an increased MPV in NAFLD may, at least in part, explain the higher risk of cardiovascular pathology in this patient group. Larger platelets are metabolically more active than smaller platelets and have a higher thrombogenic potential. Interestingly, a new function of statins was described in a recently published literature review and meta-analysis: their ability to reduce MPV and exert antiplatelet activity [86]. As for antiplatelet agents, it has been demonstrated that aspirin does not affect MPV, but no data are available regarding the potential effects of other antiplatelet drugs on changes in this parameter [87].

Infiltration of liver tissues with platelets was demonstrated in animal NASH

models, as well as in human subjects with steatohepatitis. However, similar

changes were not detected in simple steatosis [16]. Platelet adhesion to

components of the liver extracellular matrix (in particular, to hyaluronic acid)

occurs through the platelet receptor CD44. This mechanism ensures the interaction

of platelets with Kupffer cells because the latter binds to the membrane

glycoprotein platelet receptor Ib

Further support for the role of platelets in inflammatory activity in NASH came

from a study that showed that genetically impaired release of platelet

In studies involving NAFLD models on mice (choline-deficient and high-fat diet models), it was shown that long before the appearance of activated Kupffer cells and hepatic stellate cells, at the stage of simple steatosis, dysfunction, and damage to LSECs develop [82, 89]. To ensure their normal functioning, LSECs require nitrogen oxide (NO), the formation of which under physiological conditions is controlled by the activity of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS). There are other isoforms of nitric oxide synthase, notably inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) and neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS), which may also be involved in NO synthesis. In conditions of hemodynamic shear stress, vasoconstriction and NO production (under the influence of insulin) are controlled by the eNOS and iNOS enzymes. However, it was shown that during inflammation it is iNOS activity that increases, which can aggravate insulin resistance and hyperglycemia, maintain oxidative stress, and inhibit eNOS expression, thereby contributing to the development of endothelial dysfunction [83]. Severe steatosis causes a hemodynamically significant increase in intrahepatic resistance that precedes inflammation and fibrogenesis. Both functional (endothelial dysfunction and increased synthesis of thromboxane and endothelin 1) and structural factors are involved. This phenomenon may contribute significantly to steatosis-related disease [84].

Moreover, LSEC dysfunction was also described to precede Kupffer cell

activation, NO reduction, NF-

Recent studies emphasize the critical role of platelets in the progression of NAFLD, indicating that their properties and functions may be considered therapeutic targets for this liver disease. For example, some studies have shown that antiplatelet drug therapy (acetylsalicylic acid, ticlopidine, cilostazol) significantly reduces the severity of hepatosteatosis in the high-fat/high-calorie (HF/HC) diet-induced NAFLD model in male Fisher 344 rats, and also reduces the activity of inflammation and fibrosis in the choline-deficient L-amino acid-defined (CDAA) diet-induced NAFLD animal model. Notably, the reduction in the severity of steatosis, inflammation, and fibrosis in rat NAFLD models was observed despite the absence of significant changes in daily calorie intake, body weight, visceral and subcutaneous fat, and adipokine levels in the animals [96]. The beneficial effect of disaggregants on the progression of NAFLD, as described in animals treated with cilostazol, was most evident [96]. Moreover, cilostazol therapy prevented the onset of simple hepatic steatosis in rats fed a high-calorie high-fat diet (HC/HF).

Regarding hypoxia as a contributing factor in the pathogenesis of NAFLD,

research has shown that in the liver tissue of rats treated with cilostazol, the

mRNA levels of VEGF, HGF, and eNOS—known for their direct angiogenic

effects—significantly increased. Concurrently, the mRNA levels of

TGF

As to aspirin therapy, a study from the Third National Health and Nutrition

Examination Survey provided data indicating that regular aspirin use (

Recently, a meta-analysis of 4 studies involving 2593 patients with NAFLD (949

patients taking antiplatelet agents and 1644 patients not receiving antiplatelet

agents) was published. The use of aspirin and/or P2Y (purinergic G

protein-coupled) 12 receptor inhibitors was linked to a lower pooled odds ratio

(OR) for advanced liver fibrosis in patients with NAFLD (pooled OR = 0.66; 95%

CI: 0.53–0.81, I2 = 0.0%; p

Considering that aspirin is a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) and a non-selective inhibitor of cyclooxygenase (COX)-2, researchers wondered if other NSAIDs might have similar effects on liver steatosis and fibrosis. In the study by Jiang et al. [106], it was established that ibuprofen, unlike aspirin, was not associated with lower values of indices for assessing liver fibrosis in patients with chronic liver diseases, including NAFLD [106]. Similar results were obtained in the work by Simon et al. [105], who showed that the intake of other NSAIDs did not contribute to the reduction in the risk of developing significant (advanced) liver fibrosis.

Vell et al. [107] established that aspirin’s beneficial effects on liver steatosis and fibrosis in NAFLD patients were only observed in men. This may be explained, at least in part, by differences in prostaglandin synthesis between the sexes [108]. Male neutrophils and macrophages are more likely to produce prostaglandins during an acute inflammatory response, whereas female cells produce more leukotrienes [109]. It may therefore be speculated that more arachidonic acid is present as a substrate for the COX enzymes that are used to produce prostaglandins [108]. Conversely, inhibition of COX enzymes may have a more pronounced effect on inflammatory prostaglandin levels in men than in women. The second reason for the difference in aspirin action between men and women may be a paradoxical attenuation of the antiplatelet effect of aspirin in response to epinephrine or ADP after 1 month of daily aspirin administration in women, which was not observed in men [110]. However, the attenuation of the effects of aspirin on platelets over time with epinephrine and ADP in women was not due to either insufficient aspirin exposure or the inability of aspirin to inhibit COX-1 in women compared with men. At the same time, Friede et al. [110] noted that the differences in platelet reactivity observed in their study were absent when samples were tested with high concentrations of platelet agonists. This may imply that the platelet pathways underlying the gender differences in platelet response to aspirin can only be detected using low concentrations of platelet agonists [110].

Nevertheless, the concept of gender-specific beneficial effects of acetylsalicylic acid on liver steatosis and fibrosis in men with NAFLD aligns with the higher prevalence of this liver disease among men [111, 112]. At the same time, the female gender is associated with a greater likelihood of NAFLD progression and the development of advanced liver fibrosis, especially in those over 50 years of age [113].

Regarding other disintegrating agents, specifically ticagrelor and clopidogrel,

available information includes a study by Lee et al. [114], who fed mice

a high-fat diet for 18 weeks, then randomized mice with an NAFLD activity score

(NAS) index

Since clopidogrel and prasugrel are prodrugs, they require hepatic transformation by cytochrome enzymes to become active substances. The reaction of clopidogrel conversion to the active metabolite is catalyzed by the cytochrome P450 isoenzyme 2C19 (CYP2C19), and dysfunction of this activation pathway is known to significantly impair the response to clopidogrel [118]. Powell et al. [119] performed a meta-analysis of 16 studies in patients with NAFLD and showed that CYP2C19 was consistently suppressed in 15 of 16 studies in patients with NAFLD. This may, at least in part, explain why clopidogrel failed to improve liver steatosis, as demonstrated in a study by Lee et al. [114]. Moreover, there are several reports documenting the hepatotoxic effects of clopidogrel [120, 121, 122], which should be considered in the context of managing patients with NAFLD.

The investigation into the potential application of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa (GPIIb/IIIa) inhibitors (tirofiban and eptifibatide) for targeting platelets in chronic liver diseases, including NAFLD, is complicated by the well-known adverse effect of this class of drugs, namely thrombocytopenia, which may already be present in patients with liver disease at the cirrhotic stage and may further exacerbate under the influence of such therapy [123].

Given the steady rise in the incidence of NAFLD, its frequent association with other chronic non-communicable diseases that can affect the course of NAFLD and patient prognosis, as well as the limited therapeutic options for this liver disease, the exploration of the pathogenesis of NAFLD to identify new therapeutic targets is undeniably topical. From this perspective, activated platelets hold significant interest. In addition to their hemostatic function, they are capable of regulating the activity of inflammatory and fibrotic processes in liver tissue through interactions with hepatocytes, stellate cells, LESCs, and Kupffer cells, as well as via the release of biologically active substances stored in various types of platelet intracellular granules. Thus, activated platelets appear to influence the development and progression of NAFLD, and consequently, disaggregants may represent a new promising direction in the treatment of NAFLD. In addition, taking into account that NAFLD is frequently associated with cardiovascular diseases requiring antiplatelet therapy, the use of these agents may also help to reduce the polypharmacy in such a category of patients. However, it should be remembered that currently the descriptions of positive effects of antiplatelet agents, primarily acetylsalicylic acid, in NAFLD are mainly based on studies conducted in animal models of NAFLD or in patients who were prescribed these agents for cardiovascular diseases. Although Simon et al. [105] recently demonstrated the efficacy of aspirin in reducing the severity of steatosis in NAFLD patients compared to a placebo after 6 months of treatment, larger randomized controlled trials are still needed to investigate the causal relationship and the potential role of different antiplatelet agents, including but not limited to acetylsalicylic acid, as antifibrotic therapy in patients at risk of liver fibrosis progression. Moreover, it is important to notice that despite the beneficial effects of antiplatelet agents on liver inflammation and fibrosis, lifestyle modification strategies, including diet and increased physical activity, remain an indispensable part of NAFLD treatment, especially considering the multifactorial nature of this liver disease.

AFS and OMD designed the review; EOL collected the literatures; AFS and OAZ analyzed the literatures; AFS and EOL prepared the original draft; OMD and ARK participated in the analysis and interpretation of data, made figures and edited the draft; OMD received funding and supervised the project. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We are grateful to all peer reviewers for their opinions and helpful suggestions.

This study was supported by the Russian Science Foundation (Project No. 23-45-10030) as part of the scientific project, Prevalence and Factors Associated with Musculoskeletal Disorders in Young and Middle-Aged Hypertensive Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease in Russian and Belarusian Populations, carried out at the National Medical Research Center for Therapy and Preventive Medicine in 2023–2025.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.