1. Introduction

Endometriosis is a benign gynecological disorder characterized by the presence

of endometrial glands and mesenchyme outside the uterine cavity and myometrium

[1]. It is an estrogen-dependent disease that affects approximately 5–10% of

women of reproductive age and is accompanied by symptoms such as infertility,

dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, and chronic pelvic pain [2]. In addition, although

endometriosis has benign pathological features, it also has cancer-like features,

such as diffusion, invasion, and hyperplasia.

Endometrial polyps (EPs) are localized hyperplastic growths of the endometrial

glands and stroma that occur in up to 25% of women [3]. EPs can cause symptoms,

such as abnormal uterine bleeding and infertility, which can occur in women of

any age. Clinical infertility studies have found that the incidence of EPs is

higher in patients with endometriosis (46.7–68.4%) than in those without

endometriosis, implying that the presence of EPs may be a key factor in causing

infertility in people with endometriosis [4, 5]. Furthermore, patients with EPs

and endometriosis have a higher probability of recurrence after polypectomy than

those without endometriosis, implying that endometriosis may be associated with

the pathogenesis of EPs [6]. In comparison to EPs, patients with endometriosis

have a longer latency period of approximately 1–5 years, such that there may be

cases where EPs are detected without endometriotic lesions. Therefore,

recognition of the association between endometriosis and EPs is lacking.

Exploring the potential mechanism of the response to EP combined with

endometriosis may help in the early screening of patients with EPs with or

without endometriosis.

Recently, patients with endometriosis have been reported to exhibit a

cancer-like glycolytic phenotype [7]. Endometriotic growth is promoted by

increased glucose metabolism, and aberrant levels of glycolytic enzymes are

detected in endometriosis-derived endometrial stromal cells (ESCs) [8, 9]. The

key role of pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) in the regulation of glycolysis has been

emphasized in a previous study [10]. It has been shown that oxaloacetate boosts

aerobic glycolytic effects by facilitating PKM2 activity [11]. In response to the

decrease in PKM2 activity, monomeric and dimeric forms of PKM2 translocate into

the nucleus, where they interact with hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha

(HIF-1) and mediate the expression of multiple pro-glycolytic enzymes

[12]. Available evidence suggests a pro-promotional role of PKM2 in endometriosis

[9, 13]. Increased evidence demonstrates that HIF-1 expression levels

are significantly increased in clinical endometriosis samples [14, 15].

Furthermore, the inhibition of HIF-1 helps to arrest the progression of

endometriosis, indicating that HIF-1 plays a key role in endometriosis

[16]. At present, the PKM2/HIF-1 axis plays a vital role in

glycolysis-related diseases, but its role in patients with EPs with endometriosis

has not been established.

Therefore, we focused on investigating the function and mechanism of action of

the PKM2/HIF-1 axis in EPs combined with endometriosis, which will help

to better understand the correlation between the two diseases and improve their

clinical diagnosis and treatment.

2. Methods and Materials

2.1 Patients’ Samples

Forty-one patients with EPs who underwent hysteroscopic surgery at Dongying

People’s Hospital during their menstrual augmentation period were enrolled in the

study. The excised EP samples were divided into endometriosis (n = 23) and

non-endometriosis (n = 18) groups, depending on the presence or absence of

endometriosis. Patients with EPs, systemic inflammatory diseases, a history of

hormonal therapy within 3 months prior to the operation, uterine malformations,

uterine adhesions, endometrial dysplasia, malignant neoplasia, or uterine

fibroids were excluded. One portion of the EP samples was fixed with 4%

paraformaldehyde (#G1101-500ML; YuBioLab, Beijing, China) and subjected to

paraffin embedding for immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis, while the other

portion was used to isolate primary ESCs. The study was carried out in accordance

with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics

Committee of Dongying People’s Hospital (Approval Number 2024 [019]), and written

informed consent was obtained from all patients or their families/legal guardians prior to tissue sample

collection.

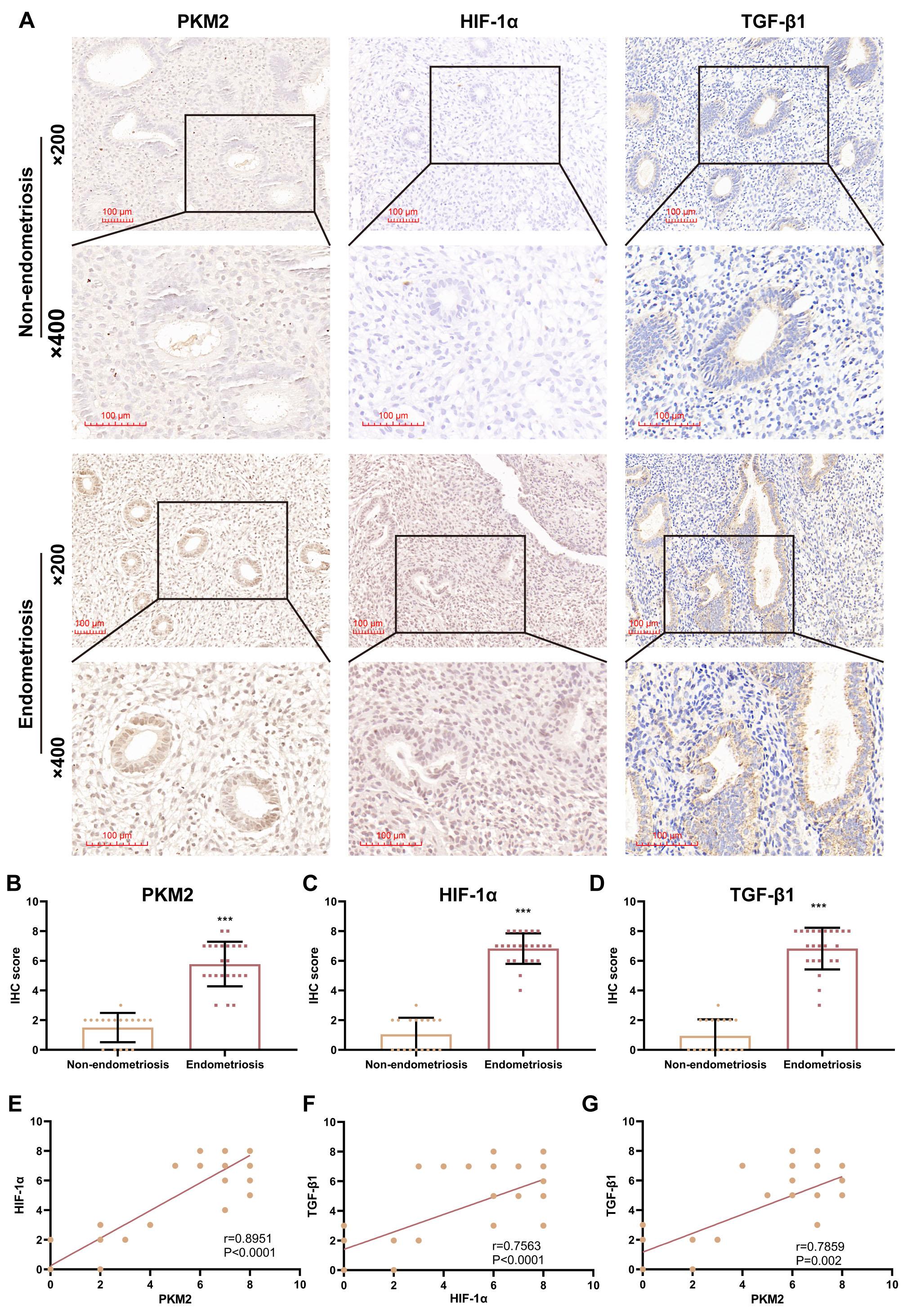

2.2 Tissue IHC Analysis

Protein expression levels and cellular localization of PKM2, HIF-1,

and transforming growth factor-beta 1 (TGF-1) in EP samples derived from

endometriosis and non-endometriosis groups were measured using IHC analysis.

Briefly, 4-µm-thick sections were prepared from paraffin-fixed

samples and mounted on silane-coated glass slides. Rehydration was performed in

serial dilutions of ethanol using a dewaxing reagent (#ST975; Beyotime,

Shanghai, China). Endogenous peroxidase activity was quenched using 1% hydrogen

peroxide (#7722-84-1; Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) for 15 min. After washing, the sections were incubated with primary

antibodies against PKM2 (#bs-0101R-1; Bioss, Beijing, China), HIF-1

(#ab51608; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA), and TGF-1 (#ab215715; Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA) at

4 °C overnight. Horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG

(#ab97051; Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was added and the samples were incubated for 25

min. After washing, the sections were incubated in 3,3-diaminobenzidine

(#A690009; Sangon, Shanghai, China) in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) for 10

min and counterstained with hematoxylin to allow visualization of the immune

complexes. Images were obtained using a microscope (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan).

All slides were scored by an independent pathologist who was not informed of the

sample characteristics, and the fields of view were randomly selected at a

magnification of 400. IHC results of PKM2, HIF-1, and

TGF-1 were quantified using the Allred score [17], which is the sum of

the scores of the proportion of positive cells (score range, 0–5) and the

response intensity (score range 0–3). The percentage of positive cells was

scored as follows: absence of positive cells, 0; 1% positive cells, 1; 2–10%

positive cells, 2; 11–30% positive cells, 3; 31–66% positive cells, 4; and

67–100% positive cells, 5. The staining intensity was defined as follows: 0,

negative (no staining); 1, weakly positive (yellow); 2, moderately positive

(brown-yellow); and 3, strongly positive (brown). Five fields of view were

randomly selected for each sample and the results were analyzed using the

semi-quantitative method. To avoid false positives or negatives, the primary

antibody was replaced by PBS as a negative control, and tissues with known

positive expression of PKM2, HIF-1, and TGF-1 were used as

positive controls. The EP tissues in each group were divided into a negative

group (scores of 0 or 2) and a positive group (scores 3).

2.3 Isolation of primary ESCs and Nonendometriotic

Patient-Derived ESCs (NESCs)

Fresh EP samples collected from patients with EP with or without endometriosis

under sterile conditions were minced finely and digested enzymatically with 5 mg

of collagenase I (500 µg/mL; #17100017;

Gibco™, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1 mg

deoxyribonuclease type I (100 µg/mL; #10325ES80; Yeasen,

Shanghai, China) for 1 h at 37 °C. After centrifugation, the cells were

suspended in DMEM/F12 culture medium containing 1 nM estradiol (#IE0210;

Solarbio, Beijing, China), 0.2% insulin (#P3376; Beyotime), 1% L-glutamine

(#ST1441-25g; Beyotime), 1% antibiotic solution (#SNA-001; Sunncell, Wuhan,

China), and 10% dextran-coated charcoal-treated fetal bovine serum

(#SH30068.03; HyClone, Logan, UT, USA). The purity of the isolated ESCs was confirmed 95%

(P2-P3) by Immunocytochemistry (ICC) staining using antibodies against vimentin

(stromal cell marker) (#FNab09409; Finetest, Wuhan, China) and cytokeratin

(epithelia cell marker) (#bs-1712R; Bioss). Non-endometriotic patient-derived

ESCs were designated as control cells and named non-endometriotic patient-derived

ESCs (NESCs). ESCs and NESCs from P3-P4 were used for subsequent experiments.

2.4 Cell Transfection

Small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) targeting PKM2 (si-PKM2#1, sense:

GGAAAGAACAUCAAGAUAATT, antisense: UUAUCUUGAUGUUCUUUCCTT; si-PKM2#2, sense:

GGAAUGAACGUGGCUCGUUTT, antisense: AACGAGCCACGUUCAUUCCTT; or si-PKM2#3, sense:

GGGUGAACUUGGCCAUGAATT, antisense: UUCAUGGCCAAGUUCACCCTT) were utilized to

interfere with PKM2 expression in ESCs, with si-NC (sense: UUCUCCGAACGUGUCACGUTT,

antisense: ACGUGACACGUUCGGAGAATT) used as a control. A PKM2-overexpressing

(PKM2-OE) plasmid was constructed by inserting the cDNA sequence of PKM2

(NM_002654.6) into pcDNA3.1, with an empty vector as a control. siRNAs (10 mM)

were transfected into ESCs using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA,

USA). The PKM2-OE plasmid was transfected using Lipofectamine 3000 (Invitrogen)

according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.5 Reverse Transcription (RT)-Quantitative Polymerase Chain

Reaction (qPCR)

TRIzol reagent (#15596026; Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to extract total

RNA from ESCs or NESCs. The purity and concentration of the RNA were verified by

measuring the absorbance ratio at 260/280 nm. Subsequently, cDNA

was generated using M-MLV reverse transcriptase (#AE101-03; TransGen Biotech,

Beijing, China). qPCR was performed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix

(#1725121; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). PCR primers were synthesized by TsingKe

(Beijing, China). PKM2 expression was analyzed using the forward primer,

5′-ATGTCGAAGCCCCATAGTGAA-3′, and reverse primer,

5′-TGGGTGGTGAATCAATGTCCA-3′ and TGF-1 expression was

analyzed using the forward primer, 5′-TACCTGAACCCGTGTTGCTCTC-3′ and the

reverse primer, 5′-GTTGCTGAGGTATCGCCAGGAA-3′. The transcript levels of

PKM2 were normalized to those of the housekeeping gene -actin

(actin), which was measured using the forward primer,

5′-CACCATTGGCAATGAGCGGTTC-3′ and reverse primer,

5′-AGGTCTTTGCGGATGTCCACGT-3′. The 2-ΔΔCq method

was applied to calculate the relative expression levels.

2.6 Western Blotting

Cell samples were lysed in ice-cold RIPA buffer (#R0010; Solarbio) supplemented

with a protease inhibitor cocktail (#C600386; Sangon). Protein levels were

quantified using a Pierce BCA kit (#23225; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Equal

amounts of protein (approximately 50 µg) were separated by 12% sodium

dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and then transferred to

polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (0.45 µm; #88585; Thermo Fisher

Scientific). Following blocking in 5% fat-free milk, the membranes were

incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against PKM2

(#bs-0101R-1; Bioss), TGF-1 (#ab215715; Abcam), or actin (#bs-0061R;

Bioss). After incubation, the membranes were incubated with a

horseradish-peroxidase-labeled goat anti-rabbit secondary antibody (#ab97051;

Abcam). Protein bands were detected using Dura Extended Duration Substrate

(#34075; Thermo Fisher Scientific). Band intensity was evaluated using ImageJ

software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA; version 1.5) and normalized to the band

intensity of actin.

2.7 Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) Assay

ESCs/NESCs were plated on 96-well plates and incubated with or without an

anti-TGF-1 antibody (1 µg/mL) for 48 h. To each well, 250 µL

of CCK-8 solution (#C0039; Beyotime) was added. Two hours later, the absorbance

at 450 nm was recorded using a plate reader (Biotek, Winooski, VT, USA; Elx808).

2.8 Wound-Healing Assays

ESCs/NESCs (1 105) were seeded in 12-well plates and incubated

until a subconfluent monolayer was formed. A sterile pipette tip

(200 µL) was used to make a scratch-wound in the confluent

monolayers. The cells were further cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle medium

(DMEM)/F12, with or without an anti-TGF-1 antibody for 24 h. Images were

obtained using an inverted microscope and analyzed using ImageJ software.

2.9 Transwell Invasion Assay

ESCs/NESCs (1 105) suspended in serum-free DMEM/F12 were seeded

into the upper chambers of 24-well Transwell plates pre-coated with Matrigel

(#356234; Corning, New York, NY, USA) and diluted at a ratio of 1:3. To the

lower chamber, 10% fetal-bovine-serum-supplemented DMEM/F12 (600

µL), with or without an anti-TGF-1 antibody, was added.

Non-invasive cells were removed from the upper chambers after 24 h of incubation,

and the remaining cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with

0.1% crystal violet (#E607309; Sangon) for 30 min. Observation and photography

were performed under an inverted microscope, and counting was performed using

ImageJ software.

2.10 Measurement of Glucose Uptake and Lactate Production

Transfected and non-transfected ESCs/NESCs (1 105) were

incubated for 24 h under different treatments, followed by collection of the

culture media. Quantification of glucose and lactate levels in the cell culture

medium was performed using a glucose assay kit (#GAGO20-1KT; Sigma Aldrich, St

Louis, MO, USA) or a lactate assay kit (#ab65330; Abcam), respectively,

according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.11 Measurement of TGF-1

TGF-1 levels in the supernatants of ESCs/NESCs were determined using an

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kit (#PT880; Beyotime) according to

the manufacturer’s instructions.

2.12 Immunofluorescence (IF)

Cells coated on glass covers were allowed to grow overnight to prepare the

slides, which were then fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde. After permeabilization

with 0.2% Triton X-100 (#9002-93-1; Solarbio), the cells were blocked with 1%

bovine serum albumin (#9048-46-8; Solarbio) and then incubated with a primary

antibody against HIF-1 (#ab51608; Abcam) for 12 h at 4 °C.

They were then washed with PBS and incubated with a fluorescently labeled

secondary antibody (#ab150079; Abcam) for 1 h in the dark. Cell nuclei were

stained with 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (#E607303; Sangon) at a

concentration of 1.43 µM (blue). The cells were observed and imaged

using a fluorescence microscope (Olympus).

2.13 Determination of HIF-1 Gene Promoter Activity

Transfected and non-transfected ESCs/NESCs were transiently transfected with the

pGL3-HIF-1-promoter vector (0.5 µg) together with

the Renilla luciferase plasmid phRL-TK (#E2231; Promega, Madison, WI,

USA) using Fugene HD transfection reagent (#E2311; Promega) and incubated with

or without an anti-TGF-1 antibody. A double-luciferase reporter assay

system (#E1910; Promega) was used to detect luciferase activity.

2.14 Statistical Analysis

Data presented in this paper represent at least three independent experiments

and are expressed as the mean standard deviation. Statistical analyses

were performed using GraphPad Prism software (version 8.0; GraphPad, San Diego,

CA, USA). The normality of the data was determined using the Shapiro-Wilk test.

Comparisons between two groups were conducted using an unpaired Student’s

t-test. Data from more than two groups were analyzed using one-way

analysis of variance, followed by Tukey’s post-hoc test. The correlation of IHC

scores among PKM2, HIF-1, and TGF-1 in all EP samples was

analyzed using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. p 0.05 was

considered statistically significant.

3. Results

3.1 The Expression Level of PKM2 is Positively Correlated with

HIF-1 and TGF-1 in EP Samples from Patients with EPs and

Endometriosis

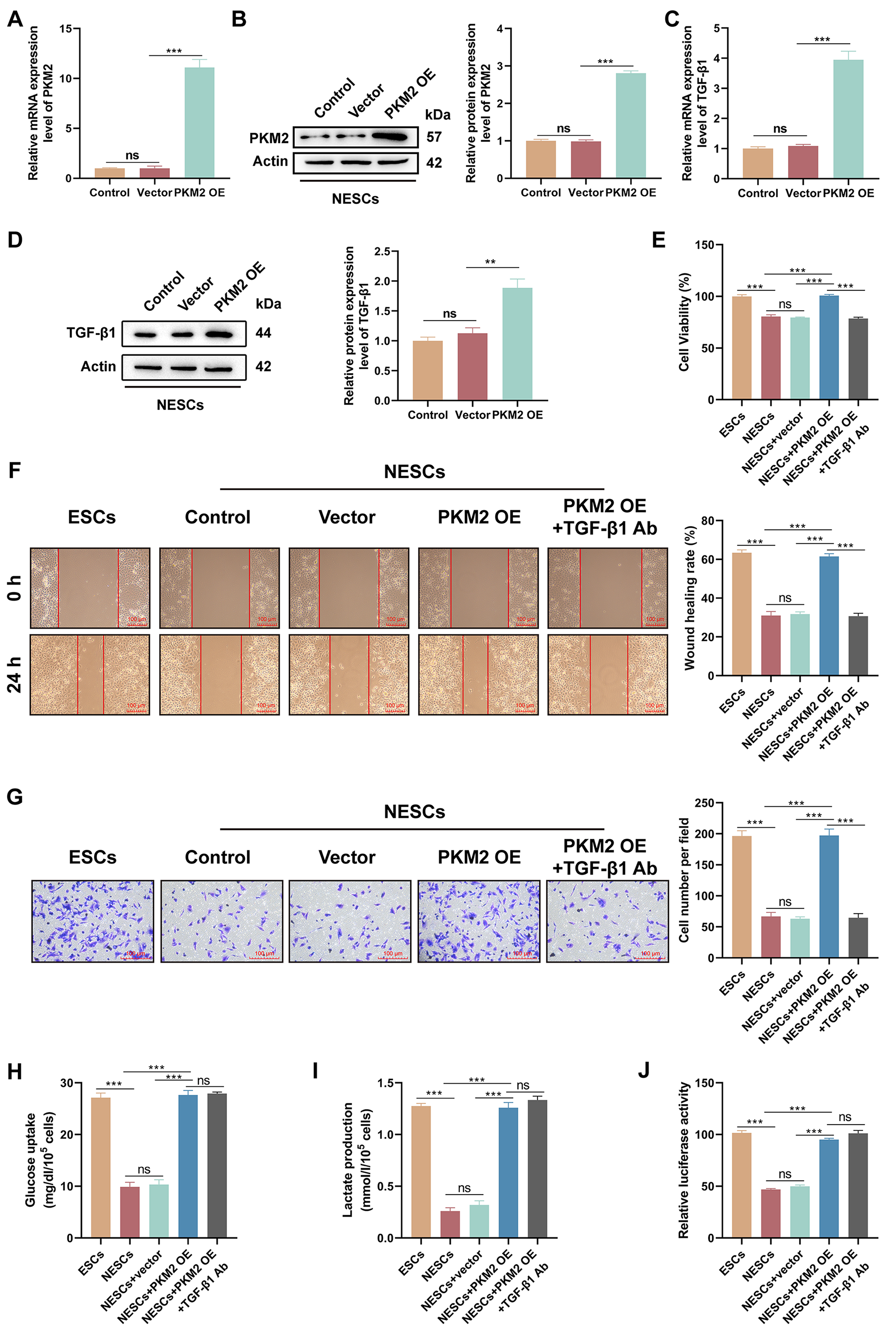

To explain the relationship between PKM2, HIF-1, and TGF-1 in

patients with EPs and endometriosis, we performed IHC staining of EP samples from

patients with EPs, with or without endometriosis (Fig. 1A). IHC staining

identified significantly higher protein levels of PKM2 (p 0.0001),

HIF-1 (p 0.0001), and TGF-1 (p

0.0001) in EP samples combined with endometriosis (n = 23) than in EP samples

without endometriosis (n = 18), with PKM2 and HIF-1 primarily localized

in nucleus and cytoplasm, but TGF-1 preferentially localized in the

cytoplasm (Fig. 1A–D). Additionally, a positive correlation on IHC scores in all

EP samples was observed between HIF-1 and PKM2 (r = 0.8951, p 0.0001), HIF-1 and TGF-1 (r = 0.7563, p

0.0001), as well as PKM2 and TGF-1 (r = 0.7859, p = 0.002)

(Fig. 1E–G). These results suggested that PKM2, HIF-1, and

TGF-1 may be involved in the pathogenesis of EPs combined with

endometriosis.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Pyruvate kinase M2 (PKM2) levels are positively correlated with

hypoxia-inducible factor-1 alpha (HIF-1) and transforming growth

factor-beta 1 (TGF-1) levels in patients with endometrial polyp (EP).

(A) Representative images (200 and 400) of

immunohistochemical (IHC) staining for PKM2, HIF-1, and TGF-1

in EP samples from patients with EPs with or without endometriosis. Scale bars:

100 µm. (B–D) Scatterplots showing IHC scores for PKM2, HIF-1,

and TGF-1 in patients with EP with (n = 23) and without (n = 18)

endometriosis (***p 0.001; unpaired Student’s t-test).

(E–G) Correlation analysis of PKM2, HIF-1, and TGF-1 IHC

scores in all EP samples (n = 23). Bars represent the mean standard

deviation (SD).

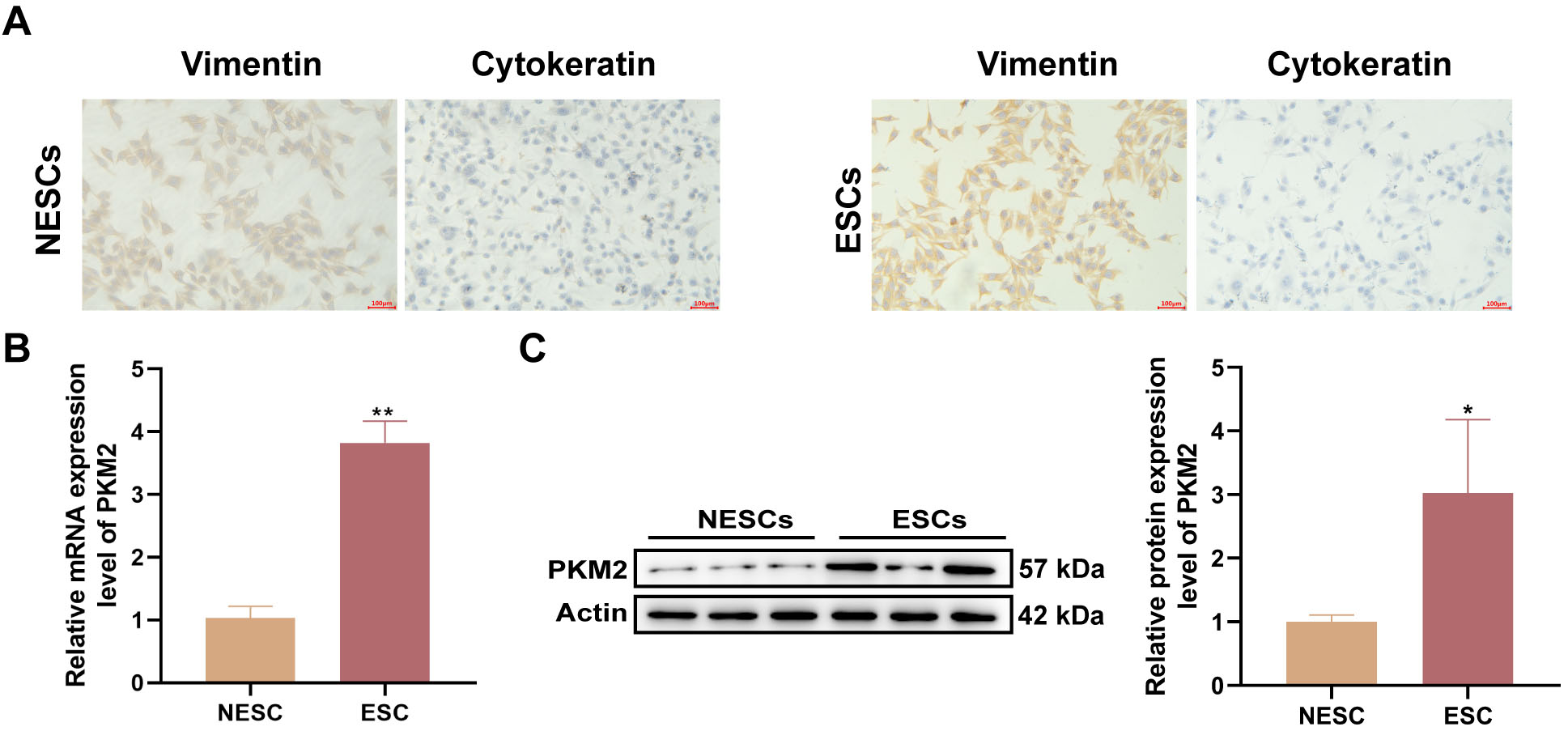

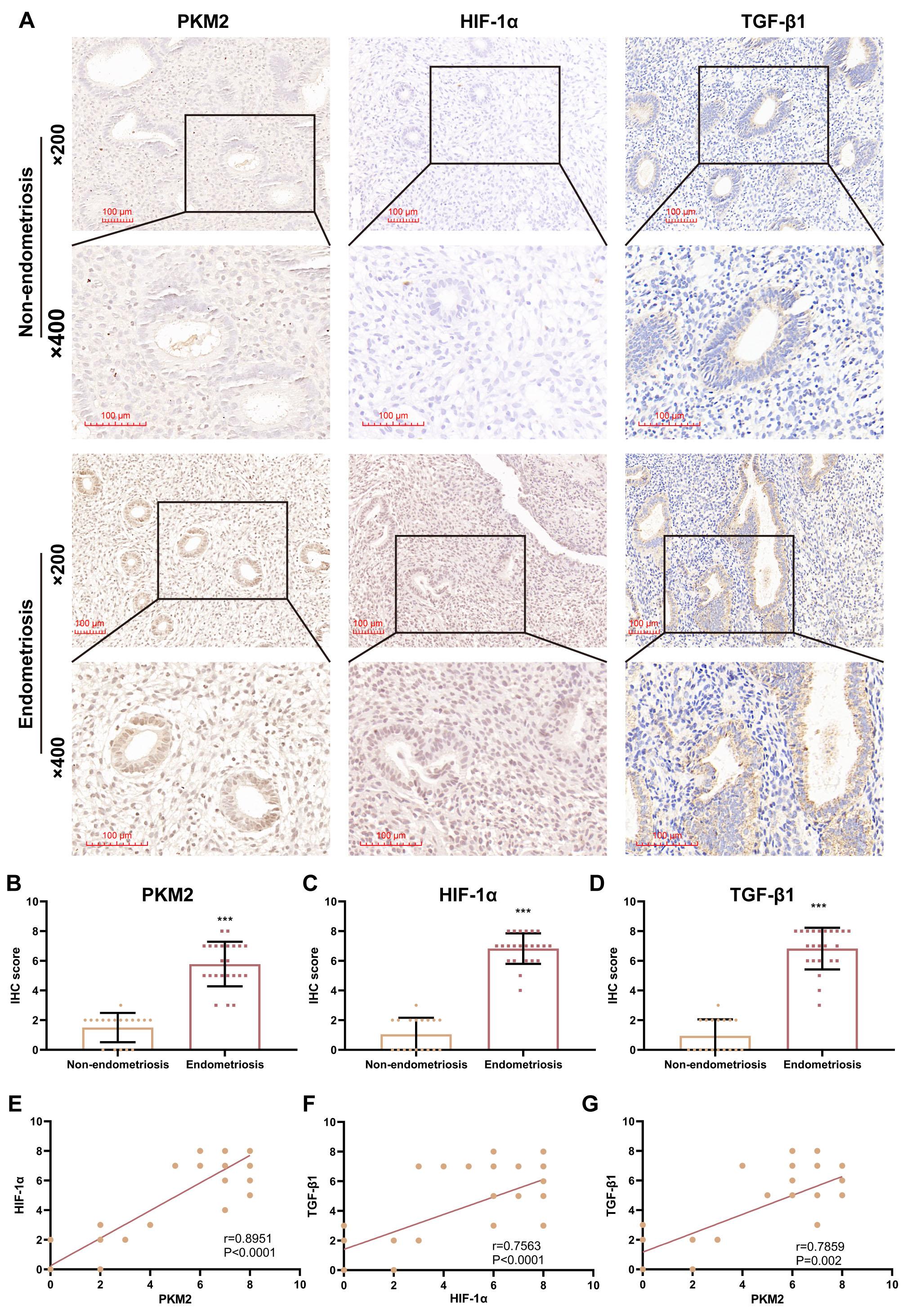

3.2 PKM2 is Highly Expressed in Primary ESCs

To analyze PKM2 function, we isolated ESCs and NESCs from EP samples obtained

from patients with and without endometriosis. The purity of the ESCs and NESCs

was determined by ICC staining using anti-vimentin and anti-cytokeratin

antibodies. As illustrated in Fig. 2A, the purity of ESCs and NESCs exceeded 95%

after passaging for 2–3 generations. Subsequently, PKM2 expression at the

transcriptional and translational levels were assessed. The data also show higher

mRNA (p = 0.0021) and protein (p = 0.0388) levels of PKM2 in

ESCs than in NESCs (Fig. 2B,C). Taken together, these results suggested that high

PKM2 levels may be related to EPs combined with endometriosis.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

High levels of PKM2 are observed in primary ESCs. (A)

Representative images of ICC staining for vimentin and cytokeratin in primary

endometrial stromal cells (ESCs) and non-endometrial patient-derived ESCs

(NESCs). Scale bars: 100 µm. (B,C) Relative mRNA and protein levels of PKM2

in primary ESCs and NESCs were detected by reverse transcription

(RT)-quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and western blotting,

respectively (n = 3; *p 0.05 and **p 0.01;

unpaired Student’s t-test). All bars represent the mean SD.

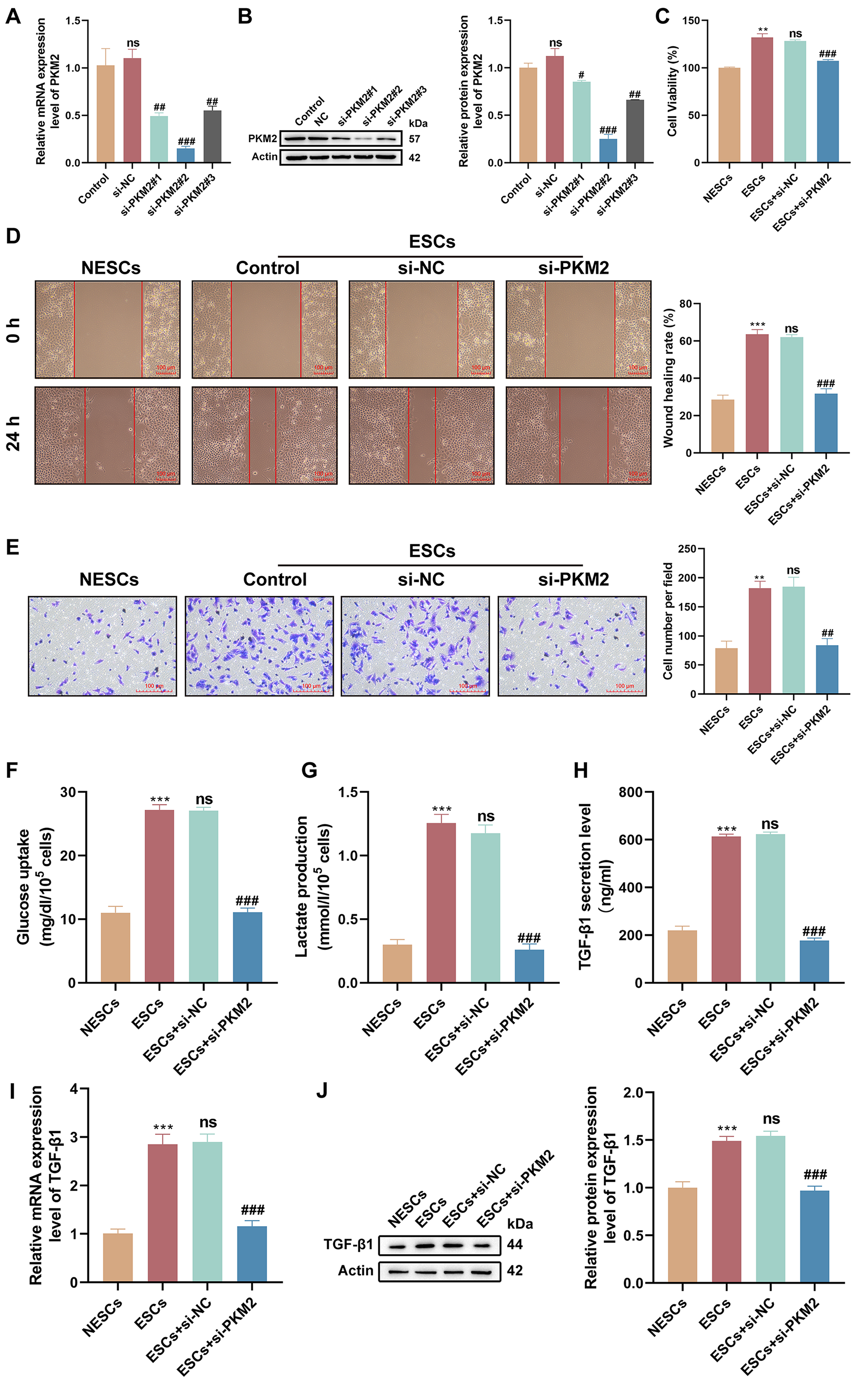

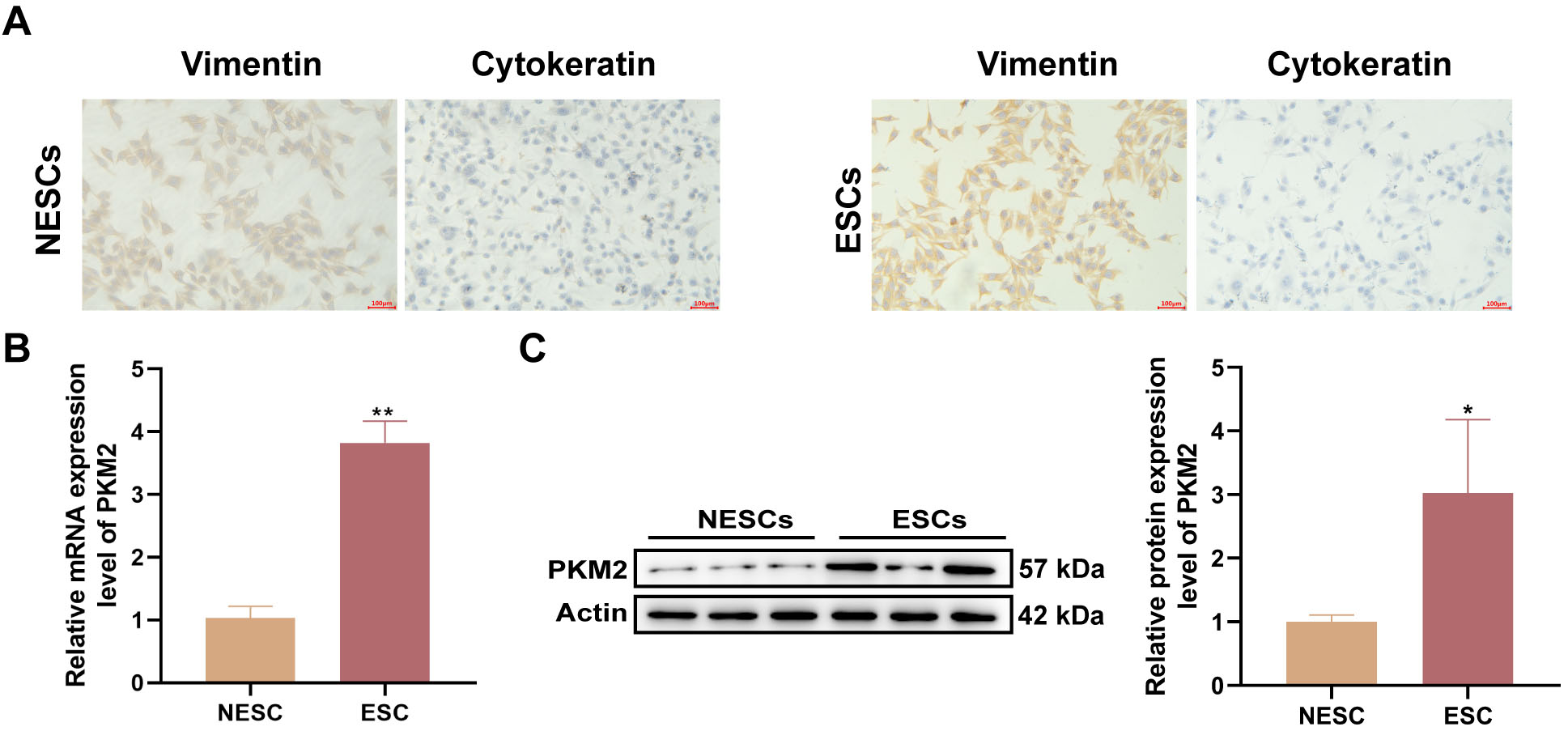

3.3 PKM2-Dependent Glycolysis Affects the Proliferative, Migratory,

and Invasive Capacities of ESCs

Considering the up-regulation of PKM2 in ESCs, we investigated the function of

PKM2 by interfering with PKM2 expression in ESCs using si-PKM2#1, si-PKM2#2, or

si-PKM2#3. All three siRNAs repressed PKM2 at both transcriptional and protein

levels, and si-PKM2#2 (p = 0.0002 and p 0.0001;

si-PKM2#1, p = 0.0078 and p = 0.0427; si-PKM2#3, p =

0.0158 and p = 0.0017), which had the best knockdown efficiency, was

selected for subsequent analyses (Fig. 3A,B). We observed higher viability in

ESCs in comparison to NESCs (p 0.0001), but the viability of ESCs

was impaired after PKM2 knockdown (p = 0.0002), as evidenced by CCK-8

assays (Fig. 3C). Furthermore, ESCs possessed stronger migratory (p

0.0001) and invasive (p = 0.0022) abilities than NESCs; however, PKM2

down-regulation reduced the migratory (p 0.0001) and invasive

(p = 0.0027) abilities of ESCs (Fig. 3D,E). As an important regulator of

glycolytic enzymes, PKM2 promotes lactate production and metabolic reprogramming.

Therefore, we investigated the effect of PKM2 on glycolysis in ESCs. The results

showed a striking increase in glucose uptake (p 0.0001) and lactate

production (p 0.0001) in ESCs versus NESCs; however, these features

of ESCs were undermined upon PKM2 knockdown (glucose uptake, p 0.0001; lactate production, p 0.0001) (Fig. 3F,G). Previous reports

have demonstrated the regulatory role of PKM2 in TGF-1 signaling [18, 19], we determined the effect of PKM2 on TGF-1 in ESCs. As expected, a

greater amount of TGF-1 was released from ESCs than NESCs (p 0.0001), but the silencing of PKM2 reduced the release of TGF-1 from

ESCs (p 0.0001) (Fig. 3H). Consistently, TGF-1 mRNA and

protein levels were strongly elevated in ESCs compared with those in NESCs

(p = 0.0001 and p = 0.0006), yet PKM2 silencing repressed

TGF-1 mRNA and protein levels in ESCs (p = 0.0002 and

p = 0.0004) (Fig. 3I,J). Collectively, these results showed that

PKM2-dependent glycolysis affects the proliferation, migration, invasion, and

TGF-1 secretion of ESCs.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

PKM2-dependent glycolysis affects the proliferation, migration,

and invasion of ESCs. (A,B) The PKM2-interference efficiency of

si-PKM2#1, si-PKM2#, and si-PKM2#3 in ESCs was detected by reverse transcription (RT)-quantitative polymerase

chain reaction (qPCR) and western

blotting (n = 3; ns, p 0.05 vs. control, #p

0.05, ##p 0.01, and ###p 0.001 vs. the

negative control small interfering RNAs (siRNAs) [si-NC]; one-way analysis of variance [ANOVA]). (C–E) The

viability, migration, and invasion of NESCs, ESCs, and ESCs transfected with

si-NC or si-PKM2 were determined by Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8), wound-healing,

and Transwell invasion assays (n = 3; **p 0.01 and

***p 0.001 vs. NESCs, ns, p 0.05 vs. ESCs, and

##p 0.01 and ###p 0.001 vs. ESCs +

si-NC; one-way ANOVA). Scale bars: 100 µm. (F,G) Glucose uptake and lactate production were measured

in different subgroups of cells using respective kits (n = 3; ***p 0.001 vs. NESCs, ns, p 0.05 vs. ESCs, and ###p 0.001 vs. ESCs + si-NC; one-way ANOVA). (H) The amount of

TGF-1 released from different subgroups of cells was measured by

enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA; n = 3; ***p 0.001 vs.

NESCs, ns, p 0.05 vs. ESCs, and ###p 0.001

vs. ESCs + si-NC; one-way ANOVA). (I,J) Relative mRNA and protein levels of

TGF-1 were determined by RT-qPCR and western blotting (n = 3;

***p 0.001 vs. NESCs, ns, p 0.05 vs. ESCs,

and ###p 0.001 vs. ESCs + si-NC; one-way ANOVA). Bars

represent the mean SD.

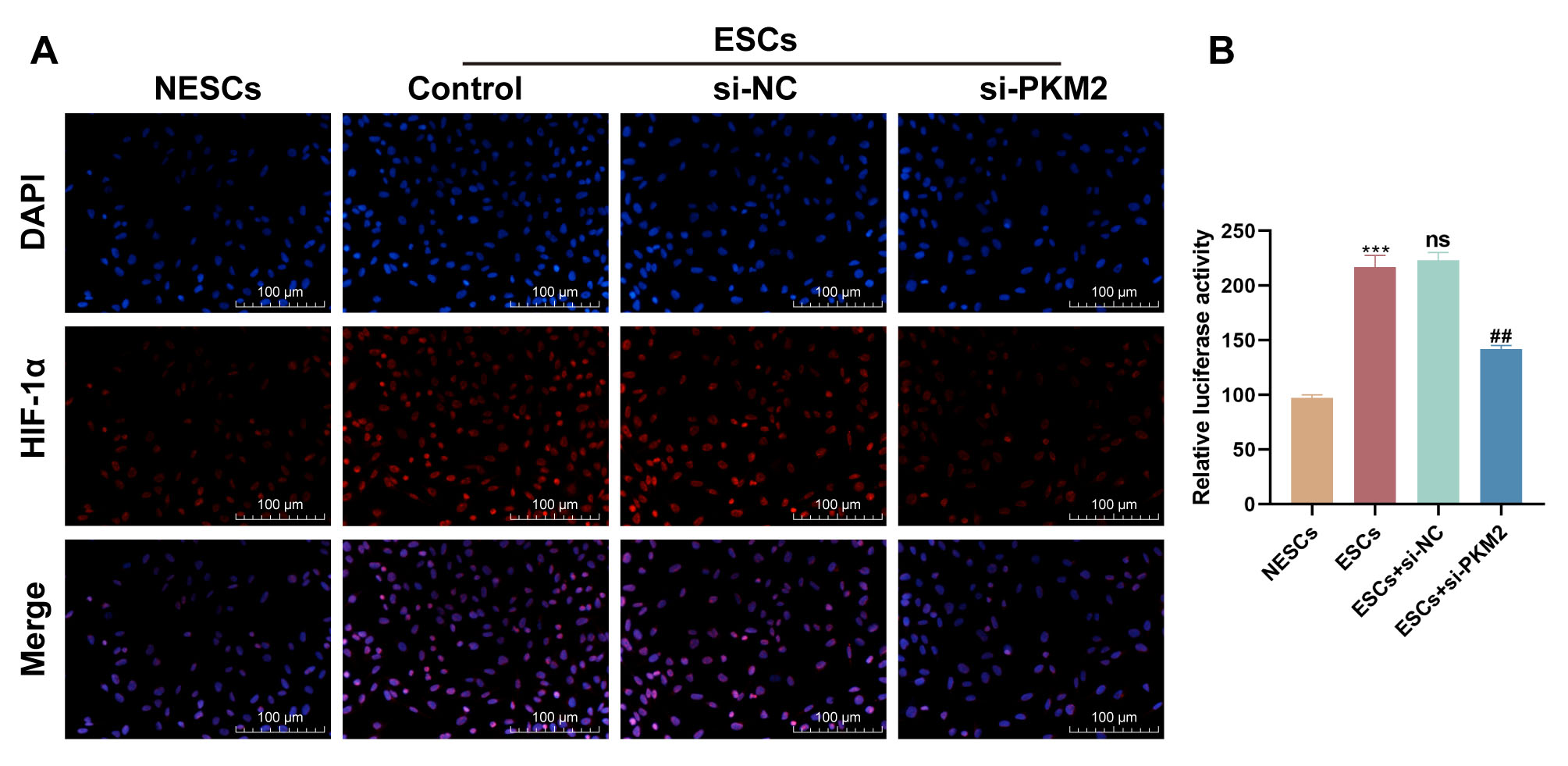

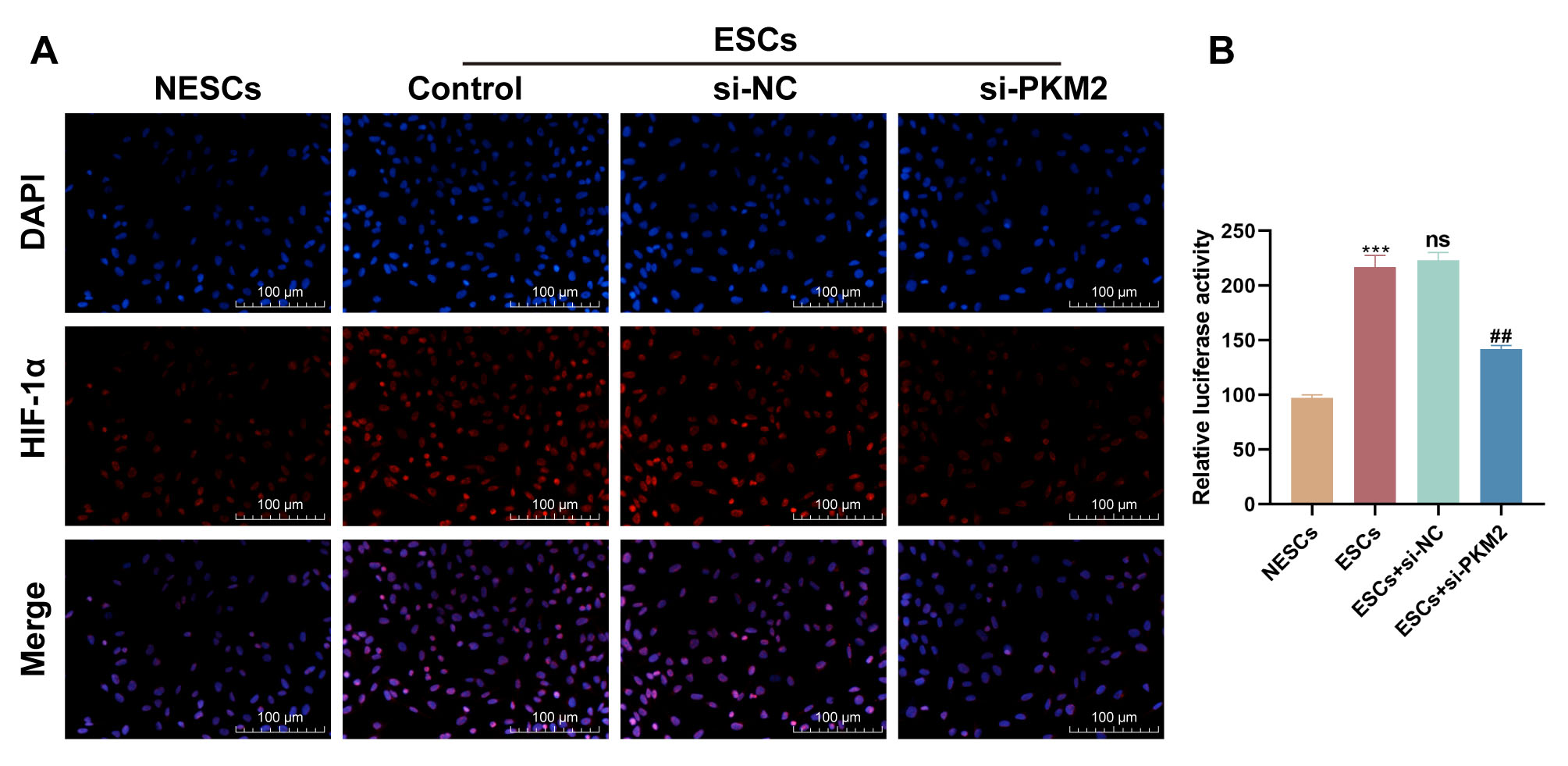

3.4 PKM2 Silencing Restrains the Transcriptional Activity of

HIF-1 in ESCs

PKM2 has been reported to interact with HIF-1 and stimulate the

HIF-1 transcriptional activation domain function. Therefore, we further

determined whether PKM2 can mediate the transcriptional activity of

HIF-1 in ESCs. IF staining showed higher levels of HIF-1 in

ESCs relative to NESCs, whereas PKM2 down-regulation repressed HIF-1

expression in ESCs (Fig. 4A). To further validate this relationship, we

constructed the luciferase reporter gene vector pGL3-HIF-1-promoter

encompassing the promoter of the HIF-1 gene. Dual-luciferase

reporter assays showed that the luciferase activity of the

pGL3-HIF-1-promoter vector was stronger in ESCs than in NESCs

(p = 0.0004) (Fig. 4B). However, the luciferase activity of the

pGL3-HIF-1-promoter vector was repressed in ESCs co-transfected with

si-PKM2 (p = 0.0027) (Fig. 4B). All results showed that PKM2 promoted

the transcriptional activity of HIF-1 in ESCs.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

PKM2 mediates the transcriptional activity of HIF-1.

(A) Representative images of immunofluorescence staining for HIF-1 in

NESCs, ESCs, and ESCs transfected with si-NC or si-PKM2. Scale bars: 100

µm. (B) Dual-luciferase reporter assays were used to determine the

luciferase activity of the pGL3-HIF-1-promoter vector in NESCs, ESCs,

and ESCs transfected with si-NC or si-PKM2 (n = 3; ***p 0.001

vs. NESCs, ns, p 0.05 vs. ESCs, and ##p 0.001

vs. ESCs + si-NC; one-way ANOVA). Bars represent the mean

SD.

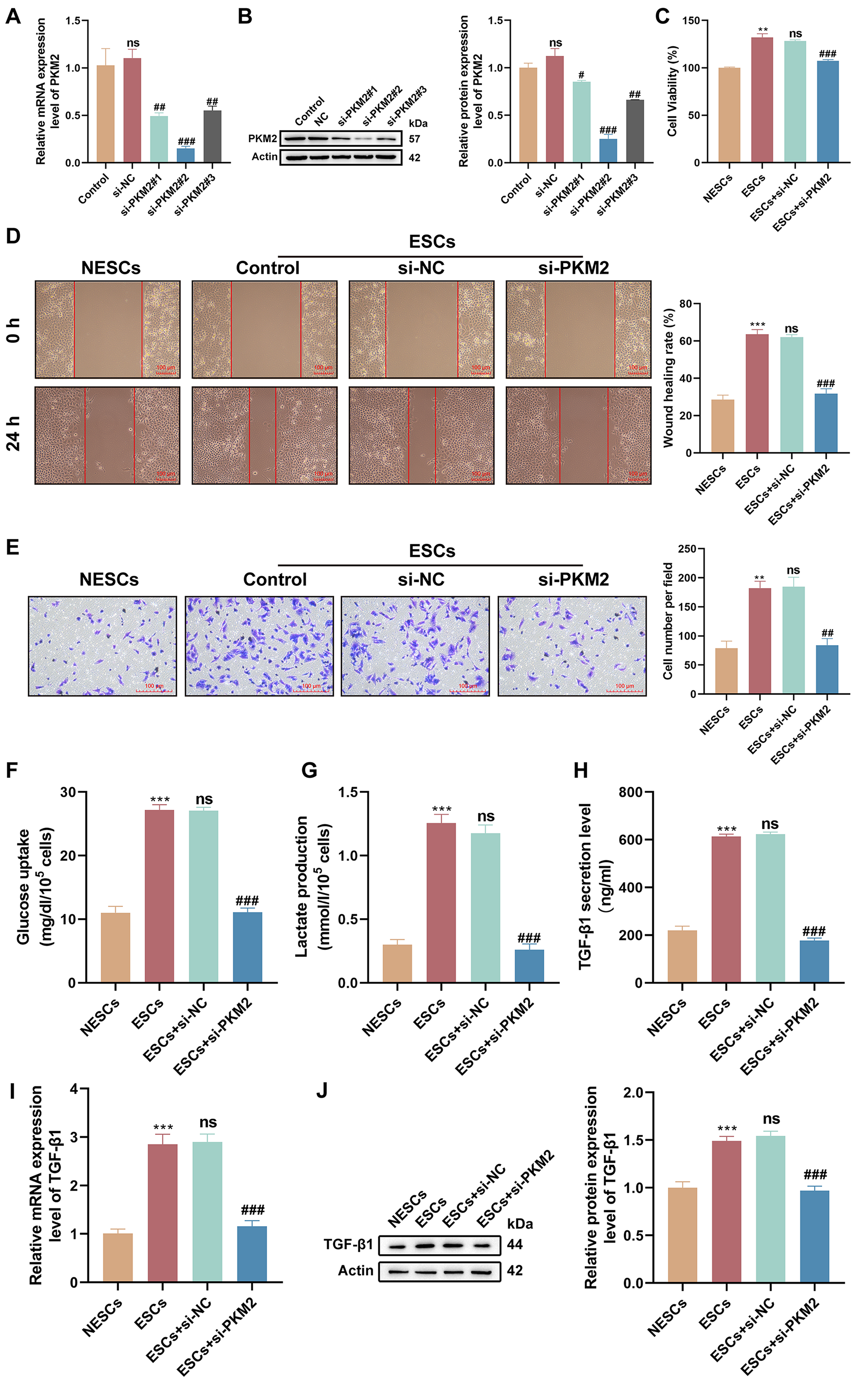

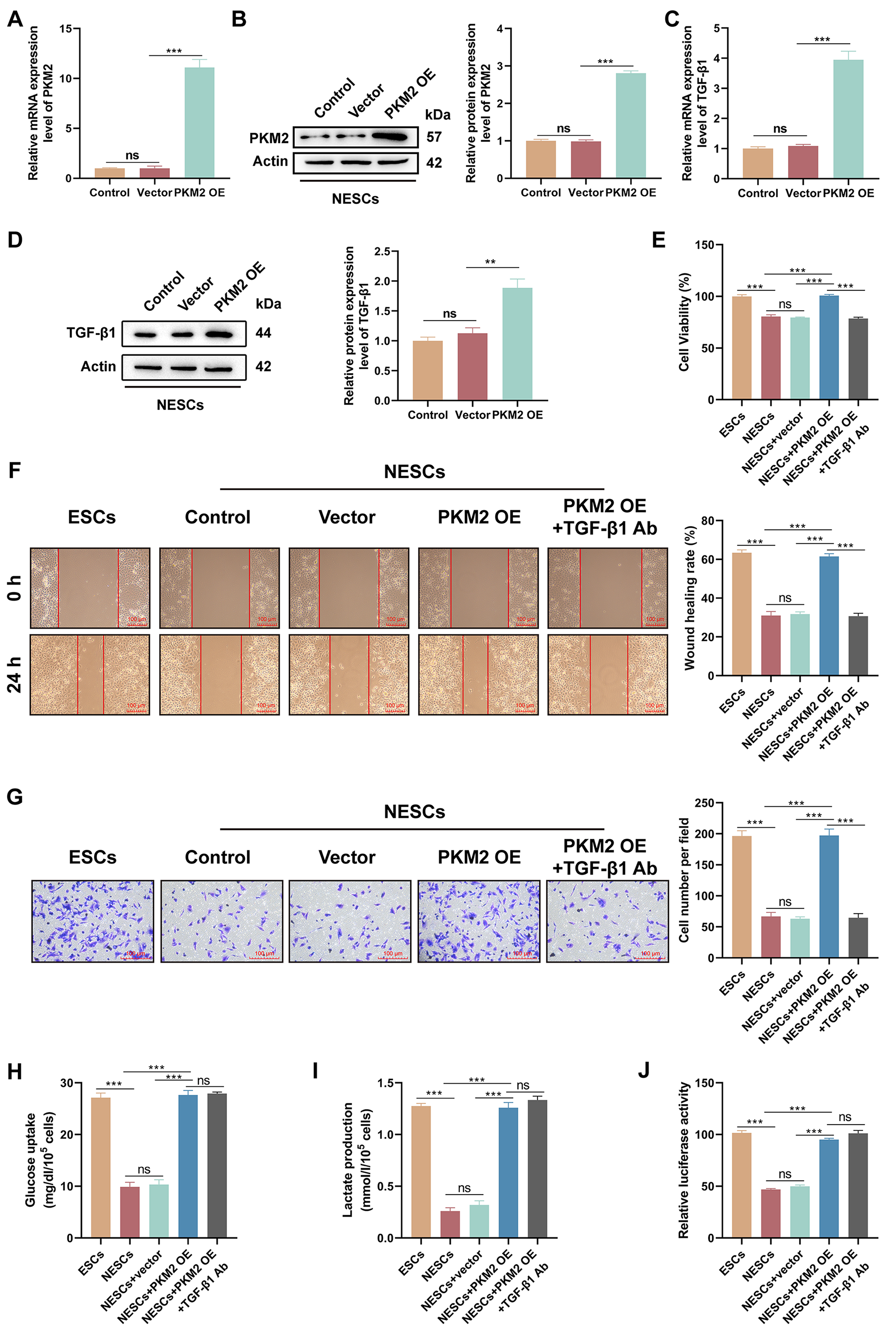

3.5 Glycolysis Mediated by PKM2 Enhances the Proliferation,

Migration, and Invasion of NESCs via TGF-1

Since up-regulation of PKM2 promotes proliferation, migration and invasion of

ESCs, we introduced PKM2 into NESCs to verify that PKM2 is a key factor in EPs

combined with endometriosis. Transfection of the PKM2-OE vector strongly

upregulated PKM2 mRNA and protein levels in NESCs (both p 0.0001)

(Fig. 5A,B). PKM2 overexpression significantly increased TGF-1 mRNA and

protein levels (p 0.0001 and p = 0.0026) (Fig. 5C,D).

Functional analyses demonstrated that PKM2 overexpression increased the

viability, migration, and invasion of NESCs (all p 0.0001), but

these effects were reversed by the introduction of an anti-TGF-1

antibody (all p 0.0001) (Fig. 5E–G), Furthermore, the up-regulation

of PKM2 markedly increased glucose uptake and lactate production by NESCs (both

p 0.0001), but the addition of an anti-TGF-1 antibody had

no effect on PKM2-mediated increases in glucose uptake and lactate production

(p = 0.9991 and p = 0.6620) (Fig. 5H,I). Importantly, PKM2

up-regulation enhanced the luciferase activity of the

pGL3-HIF-1-promoter in NESCs (p 0.0001), but the addition

of an anti-TGF-1 antibody did not affect the luciferase activity of this

promoter vector in NESCs overexpressing PKM2 (p = 0.1994), suggesting

that TGF-1 is a downstream effector molecule of the PKM2/HIF-1

axis in NESCs (Fig. 5J). Together, these data showed that PKM2/HIF-1

axis-dependent glycolysis contributes to NESC proliferation, migration, and

invasion via TGF-1.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

The PKM2/HIF-1 axis enhances the viability, migration,

and invasion of NESCs via TGF-1. (A,B) The transfection efficiency of

the PKM2- overexpression (OE) vector in NESCs was evaluated by RT-qPCR and

western blotting (n = 3; ns, p 0.05 0.05 vs. control and

***p 0.001 vs. vector; one-way ANOVA). (C,D) Relative mRNA and

protein levels of TGF-1 in NESCs and NESCs transfected with empty vector

or the PKM2-OE were determined by RT-qPCR and western blotting (n = 3;

ns, p 0.05 0.05 vs. control and **p 0.01,

***p 0.001 vs. vector; one-way ANOVA). (E–G) The viability,

migration, and invasion of cells in different subgroups (ESCs, NESCs, NESCs +

vector, NESCs + PKM2-OE, and NESCs + PKM2-OE + anti-TGF-1 antibody [Ab])

were determined by CCK-8, wound healing, and Transwell invasion assays (scale bar

= 100 µm) (n = 3; ns, p 0.05 and ***p

0.001; one-way ANOVA). (H,I) Measurement of glucose uptake and lactate production

in cells from different subgroups was performed using appropriate kits (n = 3;

ns, p 0.05 and ***p 0.001; one-way ANOVA). (J)

Luciferase activity of the pGL3-HIF-1 promoter vector was determined

using a dual-luciferase reporter assay in cells with different treatments (n = 3;

ns, p 0.05 and ***p 0.001; one-way ANOVA). Bars

represent the mean SD.

4. Discussion

A previous study has established a strong relationship between endometriosis and

EPs [20]; however, the pathogenic mechanism underlying the frequent emergence of

EPs in patients with endometriosis has not yet been fully clarified. One of the

most widely accepted theories is that estrogen affects the development of both

endometriosis and EPs [21], and a close correlation exists between the imbalance

between the proliferation and apoptosis of ESCs and these two diseases [22]. In

addition, these two disorders are associated with cytokine secretion,

immune-inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, microecological imbalances, and

metabolic disorders. Notably, there is a significant overlap in the pathogenesis

of these diseases. The pathogenesis of endometriosis combined with EPs may be a

consequence of their interactions in the same pathological environment. Another

possibility is that the emergence of one disease leads to a change in the

microenvironment, which triggers the subsequent occurrence of another disease

when the environmental change reaches a certain threshold. Therefore,

investigating the underlying mechanisms of EPs combined with endometriosis is

essential to enhance the recognition of the two diseases, prevent clinical

under-diagnosis, and reduce the risk of the mutual induction of the two diseases.

Increased glycolysis is closely associated with endometriosis progression [23].

Horne et al. [24] reported that mitochondrial respiration was

significantly reduced, and glycolysis levels were higher in peritoneal

mesothelial cells derived from the pelvic peritoneum of patients with

endometriosis. In parallel, ESCs derived from patients with endometriosis possess

metabolic reprogramming changes [25, 26]. Moreover, oral administration of the

pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH) activator dichloroacetate reduces the lactate concentration in mouse

peritoneal fluid and shrinks endometriotic lesions in mouse models of

endometriosis [24]. PKM2 is a rate-limiting enzyme in glycolysis and it promotes

the progression of endometriosis. Wang et al. [27] reported that PKM2 is

overexpressed in ovarian endometriosis, and PKM2 up-regulation mediated by PIM2

facilitates the fibrosis and glycolysis of ESCs. Furthermore, PKM2

down-regulation repressed metastasis, proliferation, and glycolysis in ESCs

derived from patients with endometriosis, via the m6A-dependent regulation of fat

mass and obesity-associated gene-mediated autophagy-related protein 5 (ATG5) expression [13]. In addition,

nuclear factor kappa B-induced transcription of PKM2 is repressed by

cinnamic acid in ESCs derived from patients with endometriosis, thus repressing

glycolysis, invasion, and viability [9]. These data highlight the promotional

role of PKM2 in endometriosis; however, its involvement in the regulation of EPs

in combination with endometriosis remains unclear. In the present study, we

isolated primary ESCs and NESCs from EP patients, with or without endometriosis,

to explore the role of PKM2. Functional experiments showed that PKM2 silencing

repressed the viability, migration, invasion, and glycolysis of primary ESCs.

However, PKM2 overexpression contributed to the viability, migration, invasion,

and glycolysis of NESCs, suggesting that PKM2 may promote behavioral changes in

NESCs towards ESCs.

It has been found that the local hypoxic microenvironment may also be an

important factor in the development of endometriosis. Severe hypoxic stress is

encountered when endometrial tissues are shed from the uterus retrogradely to the

peritoneal cavity and implanted into the ovary or peritoneum. Increasing evidence

suggests that HIF-1 is up-regulated in endometriosis and may be

involved in the invasive process of ESCs. Previous studies reported that

HIF-1 is highly expressed in the ectopic endometrium [15, 28] and it

facilitates ESC invasion, migration, and adhesion [15, 29]. Feng et al.

[30] demonstrated that nuclear translocation of PKM2 is responsible for mediating

the function of HIF-1 during the aerobic glycolytic transition. A

recent study showed that the interaction of PKM2 with HIF-1 results in

activation of HIF-1 transcriptional activity, in a process dependent on

the AC020978-induced nuclear translocation of PKM2 [31]. In this study, high

levels of HIF-1 and PKM2 were detected in nuclei in EP samples from

patients with EPs and endometriosis, and they were positively correlated with IHC

scores in all EP samples, including those with and without endometriosis. In

addition, HIF-1 was down-regulated in primary ESCs with PKM2 knocked

down, and this was coupled with lower levels of HIF-1 promoter

activity. These findings indicated that PKM2 mediates the transcriptional

activity of HIF-1 in patients with EP and endometriosis.

As a multifunctional growth factor, TGF-1 modulates diverse biological

processes, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and angiogenesis [32].

It has been reported that the levels of TGF-1 in serum, menstrual blood,

and peritoneal fluid of patients with endometriosis were substantially higher

than those of healthy women [33, 34]. Moreover, high local levels of

TGF-1 can create a suitable microenvironment, which may help ectopic

endometrial cells in the pelvis to escape immune surveillance and survive through

the regulatory effects of TGF-1 on natural killer cells and macrophages

[35]. In addition, high levels of TGF-1 may exert a role in the

formation of EPs [36]. The present study verified that TGF-1 was highly

localized in the cytoplasm in EP samples from the endometriosis group, and there

was a positive correlation among IHC scores of TGF-1, PKM2, and

HIF-1 in all EP samples. Furthermore, the elevated secretion of

TGF-1 by ESCs was reversed following PKM2 knockdown. In addition, the

promoting effects of PKM2 on NESC viability, migration, and invasion were

counteracted by the addition of an anti-TGF-1 antibody. However, the

anti-TGF-1 antibody did not affect the PKM2-mediated increase in glucose

uptake, lactate production, or the promoter activity of HIF-1 in NESCs,

suggesting that TGF-1 is a downstream effector molecule of PKM2 in

NESCs. These results manifested that TGF-1 may be involved in the

pathogenesis of EP combined endometriosis. Notably, PKM2 participates in several

diseases by regulating TGF-1 signaling [18, 19]. HIF-1 binds

to the MH2 structural domain of phosphorylated mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 3 (SMAD3) to convert the TGF-

function to glycolysis [37]. Moreover, miR-122-5p-mediated

down-regulation of HIF-1 represses TGF-1-induced cardiac

fibroblast differentiation [38]. Shi et al. [39] reported that the

restoration of epidermal cell autophagy by bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells

facilitates wound healing via the HIF-1/TGF-1/SMAD pathway in

diabetes mellitus. All of this evidence indicates that TGF-1 may be a

signaling factor acting downstream of PKM2 and HIF-1. Thus, we inferred

that the PKM2/HIF-1 axis is related to EPs with endometriosis via

TGF-1. However, one of the limitations of the present study is the

absence of confirmation of the relationship between HIF-1 and

TGF-1 by performing relevant experiments, which were explored in the

future by dual-luciferase reporter assays and rescue experiments. In addition,

the small size of the clinical sample is a limitation of this study, as it may

have made the results more subject to chance. Moreover, the selectivity of a

single-center study has bias. Therefore, an expanded sample size from

multiple-centers is needed to further validate the results in the future.

Challengingly, clinical samples and related data could not be collected from

patients with mild endometriosis combined with EPs because they were only

diagnosed but not treated.

Immune cells play a major role in the development of endometriosis and EPs, as

evidenced by the secretion of cytokines associated with processes such as

endothelial cell angiogenesis and proliferation, as well as a decreased ability

to clear ectopic endothelial cells [40, 41]. T lymphocytes are the primary

component of cellular immunity, in which T-helper 17 cells 17 (Th17) are a

subpopulation derived from the differentiation of CD4+ T cells. Th17 cells

can initiate an inflammatory response rapidly through neutrophil recruitment,

activation, and migration [42]. Over-immunization with Th17 may induce

uncontrolled neutrophil infiltration at the maternal-fetal interface [43].

Emerging evidence supports the involvement of Th17 cells in the development of

endometriosis lesions [44]. Endometriosis may be associated with increased

numbers and upregulated activity of Th17 cells in the peritoneum and ectopic

endometrial implants [45, 46]. Moreover, the increased number of Th17 cells in

the peritoneal fluid during advanced stages of endometriosis may promote the

development of lesions [47]. The increased Th17 response is observed in recurrent

EPs [48]. Interestingly, PKM2 is required for the regulation of Th17 cell

differentiation and function [49, 50]. Whether PKM2 regulates the aberrant

properties of ESCs by mediating Th17 cell activity in EPs combined with

endometriosis remains unclear and is a direction for future exploration.

5. Conclusions

In summary, PKM2-dependent glycolysis facilitates behavioral changes in NESCs

towards ESCs by increasing the transcriptional activity of HIF-1 and

promoting the secretion of TGF-1. This study helps to better understand

the pathogenesis of EPs combined with endometriosis and implies the possibility

of the combined targeting of PKM2, HIF-1, and TGF-1 for the

early diagnosis and management of EPs combined with endometriosis, with the aim

of improving the pregnancy rate of patients.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author Contributions

JJL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - original draft. LL: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing - original draft. RQF: Data curation, Investigation, Project administration, Validation, Writing - review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of Dongying People’s Hospital (Approval Number 2024 [019]), and informed written consent was received from all patients or their families/legal guardians prior to tissue sample collection.

Acknowledgment

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.