1 Laboratory of Biochemistry, Institute of Biochemistry and Physiology of Plants and Microorganisms – Subdivision of the Federal State Budgetary Research Institution Saratov Federal Scientific Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IBPPM RAS), 410049 Saratov, Russia

2 Laboratory of Microbial Genetics, Institute of Biochemistry and Physiology of Plants and Microorganisms – Subdivision of the Federal State Budgetary Research Institution Saratov Federal Scientific Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IBPPM RAS), 410049 Saratov, Russia

Abstract

Many bacteria are capable of reducing selenium oxyanions, primarily selenite (SeO32-), in most cases forming selenium(0) nanostructures. The mechanisms of these transformations may vary for different bacterial species and have so far not yet been clarified in detail. Bacteria of the genus Azospirillum, including ubiquitous phytostimulating rhizobacteria, are widely studied and have potential for agricultural biotechnology and bioremediation of excessively seleniferous soils, as they are able to reduce selenite ions.

Cultures of A.brasilense Sp7 and its derivatives (mutant strains) were grown on the modified liquid malate salt medium in the presence or absence of selenite. The following methods were used: spectrophotometric monitoring of bacterial growth; inhibition of glutathione (GSH) synthesis in bacteria by L-buthionine-sulfoximine (BSO); optical selenite and nitrite reduction assays; transmission electron microscopy of cells grown with and without BSO and/or selenite.

In a set of separate comparative studies of nitrite and selenite reduction by the wild-type strain A.brasilense Sp7 and its three specially selected derivatives (mutant strains) with different rates of nitrite reduction, a direct correlation was found between their nitrite and selenite reduction rates for all the strains used in the study. Moreover, for BSO it has been shown that its presence does not block selenite reduction in A.brasilense Sp7.

Evidence has been presented for the first time for bacteria of the genus Azospirillum that the denitrification pathway known to be inherent in these bacteria, including nitrite reductase, is likely to be involved in selenite reduction. The results using BSO also imply that detoxification of selenite through the GSH redox system (which is commonly considered as the primary mechanism of selenite reduction in many bacteria) does not play a significant role in A.brasilense. The acquired knowledge on the mechanisms underlying biogenic transformations of inorganic selenium in A.brasilense is a step forward both in understanding the biogeochemical selenium cycle and to a variety of potential nano- and biotechnological applications.

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- selenite reduction

- denitrification

- nitrite reductase

- glutathione redox system

- selenium nanoparticles

- Azospirillum brasilense

Selenium is necessary for life and is present in organisms in many different forms [1]; primarily it is incorporated into proteins in the form of the amino acid selenocysteine. Moreover, selenium has long been known as an ‘essential toxin’ [2, 3, 4], as its toxic level of human consumption (over 400 µg/day) differs from the level of deficiency (under 40 µg/day) by merely one order of magnitude [5, 6]. Replacing sulfur with a selenium atom (in the resulting selenoproteins) often accelerates the enzymatic reactions involving these enzymes [7]. Another consequence of such a replacement is that a selenium-containing biomolecule resists permanent oxidation more effectively [8], which is important for oxidative-stress-protecting enzymes. The mechanism of selenium toxicity is not yet fully elucidated [9].

Due to toxicity, selenium compounds represent a serious concern for ecosystems and living organisms [10]. As is often the case, the toxicity of Se-containing compounds depends on the chemical form of selenium [4, 11, 12, 13, 14] in the environment.

Bacteria play a primary role in the biogeochemical cycle of selenium [15, 16, 17, 18]. Bacterial strategies of interaction with selenite ions include different processes, among which the main are: assimilation, where selenite ions can serve as an inorganic source of selenium for its further incorporation into proteins [19]; detoxification, including methylation [20], reduction and dissimilation: there are a few reports about putative selenite reductases [21, 22] or association of selenite reduction with different electron transport pathways [23, 24, 25, 26]. Bioreduction of soluble and therefore potentially toxic selenite, SeIVO32- (in some cases also selenate, SeVIO42-) to insoluble Se0 in the form of nanoparticles (Se-NPs) by various microorganisms has long been documented [15, 16, 17]. Utilisation of these processes is a promising approach to selenium pollution control as well as to a number of other industrial and nanobiotechnological applications [27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33]. In particular, it is noteworthy that the resulting biogenic selenium nano-sized particles significantly differ in their structural and other physical properties from Se-NPs produced by chemical methods [15]. Besides that, biogenic Se-NPs have been documented to be capped by the bioorganic layers containing biomacromolecules produced by the organisms which reduce selenium oxyanions [27, 28].

Mechanisms of selenite reduction in bacteria include a wide variety of biochemical reactions. One of the most probable mechanisms of selenite reduction by bacteria refers to the so-called Painter-type reactions [11] involving the glutathione (GSH) redox system [11, 34] and other thiol-containing microbial metabolites [35], bacillithiol [36] or mycothiol [37]. Selenite reduction can also be supported by various reductases, including fumarate reductase [26, 38], sulfite reductase [39, 40, 41], glutathione reductase, thioredoxin reductase [42]. Importantly, such enzymes of denitrification pathways as nitrate reductase [43, 44, 45] or nitrite reductase [46, 47, 48, 49, 50] have in a few cases been reported to be involved in selenite reduction as well. It has to be mentioned that in redox biotransformations, especially those catalysed by reductases, owing to specific structures of their active site [51, 52, 53], for an enzyme there might be several substrate analogues, and this could be further facilitated by structural similarities of different substrates, particularly inorganic oxyanions to be biocatalytically reduced (cf., e.g., nitrate NO3-, sulfite SO32- and selenite SeO32-).

It has long been known that bacteria of the genus Azospirillum are capable of denitrification; they produce both nitrite and nitrate reductases [54]. Some species of these bacteria are widely used in agriculture, as they are able to colonise many different plant species and significantly improve their growth, development and productivity in the field [55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62]. It has been shown that bacteria of the genus Azospirillum could be useful for bio- and phytoremediation, as well as for more complete removal of toxic pollutants [54, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67]. However, until now, since our first publication [68], just a few original papers have been focused on studying the selenite reduction process in bacteria of the genus Azospirillum [69, 70], and the mechanisms of this process are yet to be investigated in more detail.

The aim of this study was to elucidate some features of the mechanism of selenite reduction by Azospirillum brasilense, which is one of the most studied and commercially employed species [57, 59, 61, 62, 71, 72] of associative (free-living) plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR). Bacterial growth and selenite reduction was tested during cultivation in the presence or absence of L-buthionine-sulfoximine (BSO, an inhibitor of

Strain A.brasilense Sp7 was obtained from The Collection of Rhizosphere Microorganisms (DCM 1690, according to the DSMZ-German Collection of Microorganisms and Cell Cultures GmbH, Leibniz Institute, Braunschweig, Germany; https://www.dsmz.de/collection/catalogue/details/culture/DSM-1690) maintained at the Institute of Biochemistry and Physiology of Plants and Microorganisms – Subdivision of the Federal State Budgetary Research Institution Saratov Federal Scientific Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IBPPM RAS), Saratov, Russia. The mutants of A.brasilense Sp7 (A.brasilense Sp7.1, A.brasilense Sp7.3 and A.brasilense Sp7.4) were obtained in the Laboratory of Microbial Genetics of IBPPM RAS [73, 74]. These mutants have been shown to exhibit differences in the rate of nitrite reduction.

Bacterial cultures were cultivated in a modified liquid malate salt medium (MSM) [75] which contained commonly used salts as reported elsewhere [70] and yeast extract (Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), CAS number 8013-01-2), 0.1 g

For TEM, 1–2 mL of bacterial cultures were collected by centrifugation at 10,000g for 7–10 min, washed twice in physiological saline (aqueous 0.9% NaCl) at the same mode and resuspended in physiological saline. If the optical density was too high, the samples were diluted to the desired optical density in order to obtain individual bacterial cells in TEM micrographs.

To perform TEM analyses, the samples were placed on copper grids (SPI Supplies, Structure Probe, Inc., West Chester, PA, USA) coated with formvar (1% in 1,2-dichloroethane). TEM images were obtained using a Libra-120 transmission electron microscope (C. Zeiss, Jena, Germany) at 120 kV.

L-buthionine-sulfoximine (BSO, Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA); also known as S-n-butyl homocysteine sulfoximine), a potent and specific inhibitor of

The reduction of selenite (2 mM; Na2SeO3

The cultures of A.brasilense Sp7 and its derivatives were grown as described previously, for up to 18 h, which corresponds to the end of the logarithmic and the beginning of the stationary growth phase for azospirilla in the MSM under these conditions (18 h, with shaking, aerobic conditions (180 rpm), 31–32 °C; the initial culture density was 2 × 107 cells

Bacterial cells were harvested by centrifugation in 50 mL Falcon flasks (AMS-Med Ltd., Moscow, Russia; 100 mL of culture total, Eppendorf centrifuge; 10 min, 7000g) and washed 3 times with sterile saline solution to remove the culture medium components. The resulting cell pellets were resuspended in a quarter of the initial volume (25 mL) of sterile saline solution (0.85 wt.% NaCl (JSC “REAKHIM” Ltd., Moscow, Russia) in bidistilled water).

For nitrite reduction assay, sodium nitrite (NaNO2, stock aqueous solution) was added up to a final concentration of NaNO2 of 1.5 mg

To evaluate the concentration of NO2- ions in bacterial suspensions, after every 60 min a nitrite concentration test was performed. Bacterial cells were precipitated by centrifugation and discarded. The supernatant was collected, 100 µL of the supernatant liquid was placed in the cell of 96-well polystyrene plate and 100 µL of Griess reagent was added [79]. Optical density was then measured at

For selenite reduction assay, sodium selenite (Na2SeO3

The residual concentration of selenite ions in the culture liquid after incubation of bacteria with Na2SeO3 was determined using a modified procedure of Li et al. [26], 2014. Briefly, bacterial cells and Se-NPs were precipitated by centrifugation at 12,000g for 5 min; the resulting supernatant was placed in the wells of a 96-well plate and mixed at a 1:1 ratio with 1 M ascorbic acid solution. Selenite in the supernatant was reduced to Se-NPs, staining the suspension in red. After incubation for 10 min, the colour intensity was determined as described in [26].

First of all, it was necessary to test whether the addition of BSO to the growth medium would have any effect on the growth of A.brasilense Sp7 both under normal conditions and in the presence of selenite (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Impact of BSO on the growth of A.brasilense Sp7 culture in the absence and presence of Na2SeO3 within 3 days. Data are presented as optical density (OD, at

Virtually no differences were observed in the course of A.brasilense Sp7 growth when bacteria were cultivated in the presence of selenite only or of selenite plus BSO (it was also confirmed that BSO in cell-free medium did not reduce selenite). The growth of A.brasilense Sp7 in the presence of 2 mM BSO (without selenite) was slightly retarded in comparison with the growth of the control culture by no more than ~10% after ~2 days.

Also, there were no significant differences in the processes of growth and selenite reduction after 3–7 days. As we have shown earlier [68], in the presence of selenite the lag phase elongates, during which bacteria of strain A.brasilense Sp7 adapt to the presence of 2 mM SeO32- and switch to its reductive detoxification. A weak reddish coloration of bacterial suspensions, indicating the start of selenite reduction to elementary selenium (Se0 NPs) [70], appeared after 3 d of growth both in the absence of BSO and in the presence of 2 mM BSO. After the reddish coloration of the cultivation medium appears and grows in intensity with time, this coloration starts contributing to and, accordingly, enhancing the error of the measured optical density of the culture suspension. Therefore, measuring the growth of cultures by this optical method was further incorrect. That is why the time scale in Fig. 1 is limited by 66 h.

Note that in our previous study [70], it has been proven using Raman spectroscopy (which is sensitive to the type of selenium(0) allotropic modifications) that the nanoparticles synthesized by strain A.brasilense Sp7 under these conditions consist of Se0 in its amorphous modification. The addition of BSO to the medium virtually did not influence the bacterial reduction of selenite ions. The colour of bacterial cultures containing selenite in the medium became intense after 6 days and did not differ in cultures grown in the presence of BSO and without it (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Reduction of Na2SeO3 by A.brasilense Sp7 in the presence of BSO within 6 days. Bacterial cells: 1 - without Na2SeO3 and BSO (control); 2 - in the presence of 2 mM BSO; 3 - in the presence of 2 mM Na2SeO3 and 2 mM BSO; 4 - in the presence of 2 mM Na2SeO3.

The residual concentration of selenite ions in the culture liquid appeared to be at a trace level (scarcely detectable) in both cases, which also gives evidence that the presence of BSO at least did not block the selenite reduction process in the wild-type strain A.brasilense Sp7. TEM images of bacterial cells with added Na2SeO3 showed the presence of Se-NPs formed in the course of selenite reduction both in the presence and in the absence of BSO (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM) micrographs of A.brasilense Sp7 cells grown for 6 days. (A) control (bacterial cells without Na2SeO3 and BSO); (B) in the presence of 2 mM Na2SeO3; (C) in the presence of 2 mM Na2SeO3 + 2 mM BSO; scale bar: 1 µm.

Thus it can be stated that the presence of BSO in the medium does not noticeably affect the reduction of selenite ions in A. brasiense Sp7, and therefore it can be concluded that the glutathione redox system (which is inhibited in the presence of BSO) in this bacterium evidently does not play a significant role in this process.

Since no significant differences in culture growth and in selenite reduction were observed in the presence and absence of BSO, the establishment of the degree of its influence, which is evidently low in this bacterium, requires additional special experiments that could give a quantitative assessment to evaluate the real contribution of the role of the glutathione – glutathione reductase system in this strain and other azospirilla in the selenite reduction processes.

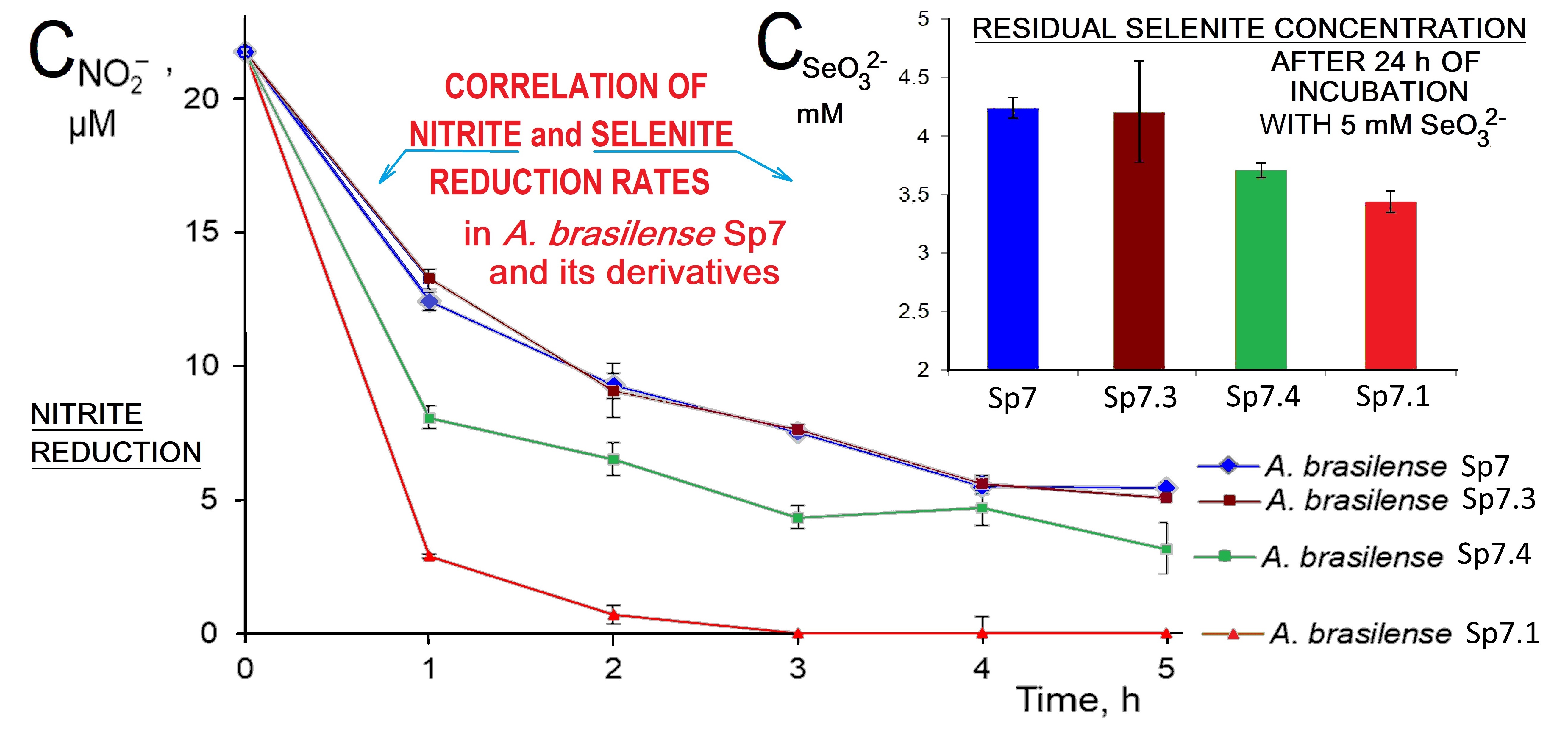

To test the participation of the denitrification system in the reduction of selenite ions in Azospirillum, we used derivatives of strain A.brasilense Sp7 [73, 74], which had differences in nitrite reduction rates: A.brasilense Sp7.1 (maximum rate), A.brasilense Sp7.3 (minimum rate, comparable to that of A.brasilense Sp7) and A.brasilense Sp7.4 (intermediate rate; see also section 4 for a more detailed description of the derivatives).

As can be seen from Fig. 4 (Ref. [73, 74]), the highest nitrite reduction rate is observed for the derivative A.brasilense Sp7.1. The derivative A.brasilense Sp7.4 also shows a higher reduction rate than that for A. brasilense Sp7. The rate of reduction of nitrite ions for A.brasilense Sp7.3 virtually coincided with that for A.brasilense Sp7.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Nitrite concentration vs. time curves showing the course of reduction of nitrite ions by A.brasilense Sp7 and its derivatives A.brasilense Sp7.1, A.brasilense Sp7.3 and A.brasilense Sp7.4 [73, 74]. The experimental points show the mean

The selenite reduction rates for the derivatives were also found to be different; differences in the colour intensity reflecting the reduction of selenite were observed during the whole incubation time. For an accurate estimation of the amount of reduced SeO32-, its residual concentration in the culture liquid of the studied samples was determined after 24 h of incubation (Fig. 5). Compared with the wild-type strain A.brasilense Sp7, the derivative A.brasilense Sp7.1 reduced two times more SeO32- (the concentration of selenite ions for A.brasilense Sp7 decreased by 0.8 mM, while for A.brasilense Sp7.1 it decreased by 1.6 mM), and for A. brasilense Sp7.4 the decrease in the concentration of SeO32- was 1.3 mM. Considering the residual concentrations of SeO32- after 24 h of incubation, the selenite reduction rates for strain A.brasilense Sp7 and its derivative A.brasilense Sp7.3 did not actually differ (Fig. 5), which also corresponds to the same nitrite reduction rate for these two strains (Fig. 4). The lowest residual selenite concentration, evidently corresponding to the fastest selenite reduction, was in the case of the derivative A.brasilense Sp7.1 (Fig. 5) which also exhibited the maximum nitrite reduction rate (Fig. 4), whereas the highest residual selenite concentration (corresponding to the minimal selenite reduction rate) was observed for A. brasilense Sp7.3 with the minimum nitrite reduction rate comparable to that of the wild-type strain Sp7 (Figs. 4,5). The derivative A.brasilense Sp7.4 showed intermediate rates of both nitrite and selenite reduction (Figs. 4,5). Thus, for the studied wild-type strain A.brasilense Sp7 and all its mutants, the reduction rates for selenite and nitrite clearly correlated.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Concentrations of selenite ions in supernatant liquid after 24 h of incubation of A.brasilense Sp7 and its derivatives A.brasilense Sp7.1, A.brasilense Sp7.3 and A.brasilense Sp7.4 in the presence of 5 mM of Na2SeO3. (Data are presented as the mean

The results obtained indicate that the reduction of selenite ions in Azospirillum brasilense is likely to occur with the participation of the denitrification processes, which evidently involves nitrite reductase (see also the relevant discussion in section 4). This phenomenon, which has for the first time been identified in this work for the bacteria of the genus Azospirillum, is of environmental importance and requires further detailed investigation.

The ability of bacteria of the genus Azospirillum to reduce selenite (but not selenate) to Se-NPs was observed for the first time in 2014 [68]. The minimum growth-inhibitory concentration of selenite was found to be in the range of 0.08–0.3 mM for strain A.brasilense Sp7. As is known also for some other bacteria, selenite is reduced by azospirilla not in the logarithmic but in the stationary phase of growth (see [68] and references cited therein). Moreover, a significant extension of the lag phase of growth was observed for azospirilla in the presence of selenite: only after 66 h, active growth was observed with an appearing red coloration of the culture (while at 10 mM selenite, no growth and no red coloration was detected) [68]. Those observations are consistent with the growth curves at 2 mM selenite presented in Fig. 1.

Little is known about the first stage of selenium metabolism, the transport of selenates and selenites into the bacterial cell. The addition of carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone (CCCP, an efflux pump inhibitor) to the culture medium also inhibited SeO32- transport in the bacterium Selenomonas ruminantium [80]. In the PGPR Rahnella aquatilis, it has recently been found [81] that selenite uptake is only partly inhibited by both CCCP and 2,4-dinitrophenol (2,4-DNP, another protonophore) in a concentration-dependent manner (starting from some minimal selenite-uptake-inhibiting concentrations of CCCP or 2,4-DNP). As for Azospirillum brasilense, it was shown in our previous work that the reduction of selenite by washed cell suspensions treated with CCCP occurred with the formation of intracellular crystals, while in suspensions not treated with this inhibitor, the formation of extracellular spherical Se-NPs was observed [70]. This fact indicates that proton-dependent transport is not involved in the uptake of selenite by Azospirillum cells; the systems involved in the reduction of SeO32- are localised in the cytoplasm or periplasm; the nuclei of Se-NPs are carried out of the cell with the participation of proton-dependent transport, and the assembly of Se-NPs proceeds extracellularly [70].

One of the main and widely distributed pathways of intracellular bacterial reduction of selenite involves thiol groups of proteins or peptides, which is known as Painter-type reaction [11]. The range of bacteria capable of synthesising glutathione is limited to

For example, it was shown that growth of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia [77, 78] and Rhodospirillum rubrum [83] in the presence of selenite and BSO was markedly inhibited compared with their growth with selenite in the absence of BSO. This indicates the participation of glutathione in these bacteria in the reduction of selenite, allowing them to overcome its toxic effect. BSO depressed selenite reduction capacity in two strains of Burkholderia fungorum, but in one of its strains, selenite reduction decreased more significantly [84]. Those authors considered it to be likely that multiple mechanisms functioned in synergy for the reduction of selenite in both studied Burkholderia strains. For the highly selenite-tolerant bacterium Proteus penneri, the selenite reduction rate was found to be decreased more than 2-fold in the presence of BSO as compared to the control without BSO [44].

Basing on the data obtained in the present work during the cultivation of strain A.brasilense Sp7 in the presence and absence of BSO, it can be concluded that the involvement of glutathione in the reduction of selenite ions cannot be the main pathway of their detoxification in A.brasilense Sp7, since there were no significant differences in bacterial growth and selenite reduction under suppression of glutathione synthesis by BSO.

Another potential pathway for the reduction of selenite ions involves denitrification enzymes. That is possible due to the chemical and structural similarity between selenite ions and nitrate ions. For Aeromonas salmonicida in aerobic culture it was shown that the reduction of selenite ions in the presence of nitrate ions was retarded [43]. In addition, a diminished ability to reduce nitrate to nitrous oxide was shown for A.salmonicida mutants with a diminished ability to reduce selenite to Se0, which indicates the possible participation of nitrate reductase in the reduction of selenite ions in this bacterium. For Azospira oryzae it was shown that the enzyme associated with the reduction of SeO32- contained molybdenum [85]. It would seem that this bacterium involved nitrate reductase in the process of selenite detoxification. However, in Rhodobacter sphaeroides a molybdoenzyme that was responsible for selenite reduction was ruled out to be nitrate reductase, since the mutant with an eliminated expression of nitrate reductase was capable of selenite reduction [86]. For Rhizobium sullae and Rhizobium sp. strain B1, selenite reduction was suggested to be mediated by the copper-containing nitrite reductase [48, 49]. In Rhizobium selenitireducens, at least two enzymes are potentially involved in selenite reduction, one of which is a nitrite reductase [50]. The ability of nitrite reductase to participate in selenite reduction is also known for other bacterial strains [46, 47].

In the present study, selenite and nitrite reduction tests carried out using A.brasilense Sp7 and its derivatives (Figs. 4,5 and the corresponding results in section 3.2) revealed a direct correlation between selenite and nitrite reduction rates in these bacterial strains. Therefore the involvement of the denitrification pathway, and particularly nitrite reductase, in the process of selenite reduction performed by A.brasilense Sp7 may be supposed, considering the following features of the strains used in this study.

The wild-type strain A.brasilense Sp7 contains the following plasmids: ~90 MDa (p90, pRhico) and ~115 MDa (p115), as well as several plasmids, the apparent molecular masses of which exceed 300 MDa [73]. Previously, clusters of denitrification genes norCBQD and nirK-orf208-orf181 were identified in the 85 MDa plasmid of the associative bacterial strain A.baldaniorum Sp245 (earlier reclassified from A.brasilense Sp245 [87]). The norCBQD cluster contains genes encoding heterodimeric NO reductase (norCB) as well as NorQ and NorD proteins that influence the synthesis and/or activation of NirK and/or NO reductases (norQD), while the nirK-orf208-orf181 cluster contains genes encoding copper-containing nitrite reductase (nirK), a putative NO sensor with two hemerythrin domains (orf181) [88]. The 115 MDa plasmid of the type strain A.brasilense Sp7 used in this work contains a region of homology to the gene cluster nirK–orf208–orf181 on the p85 plasmid of the strain A.baldaniorum Sp245, as was proved by hybridisation with DNA fragments of these genes [88].

In the derivatives of the A.brasilense Sp7 strain used in this work (Sp7.1, Sp7.3 and Sp7.4), the p115 plasmid was eliminated and the apparent molecular weight of pRhico changed. Based on the studies performed earlier, a conclusion was made about intragenomic rearrangements and integration of p115 plasmid fragments into the pRhico plasmid and/or into other replicons. Those rearrangements caused a number of phenotypic changes, including changes in the rate of nitrite reduction [73, 74]. In addition, a comparative analysis of total DNA using PCR with primers specific to nirK-orf208, hdfR and hdfR-ccoN of p85 showed differences in the organisation of this denitrification gene cluster in the derivatives of the Sp7 strain compared to the parental strain (data not published).

In our previous work [70], we proposed a four-step general mechanism of Se-NPs synthesis by A.brasilense. Our present findings allow us to assume that the second step of this process (selenite reduction) can be mediated by nitrite reductase, while the glutathione redox system is likely to play no significant role.

Thus, in view of the data obtained in this work together with our previous findings [70], we assume that the reduction of selenite ions by A.brasilense Sp7 during incubation in the presence of SeO32- includes the following stages: (i) transport of selenite ions into bacterial cells; (ii) intracellular reduction of selenite ions with the possible involvement of nitrite reductase; (iii) the removal of Se-NP nuclei from the cells with the participation of proton-dependent transport; (iv) extracellular assembly of Se-NPs near the surface of cells with the participation of biological macromolecules found to be present at the surface of Se-NPs synthesised by this strain [89, 90], which is typical for biogenic Se-NPs of microbial origin [91].

Note that we have also found an unusual phenomenon not yet actually described for azospirilla — the ability to reduce selenate (SeVIO42-) under some conditions by strain Azospirillum thiophilum BV-S studied in our earlier work [92]. This strain has an unusual feature: it showed the capacity for lithotrophic growth coupled to oxidation of reduced sulfur compounds [93]. This may indicate the relationship of the transformation processes of selenates with some parts of the metabolic pathway of sulfur compounds in this strain. This novel important phenomenon requires further investigation.

We are aware that our research may have limitations, in particular, there is yet no direct evidence that nitrite reductase is the only enzyme responsible for selenite reduction in A.brasilense (while the involvement of several parallel selenite reduction pathways is regarded to be possible in some bacteria [44, 84]). Despite this, we believe our present work could be a starting point for further more detailed investigations on the mechanisms of selenite reduction in bacteria of the genus Azospirillum which include a number of species differing in their habitats, ecological niches and adaptation capabilities [62, 72]. Some of these PGPR, which combine agrobiotechnologically important plant-growth-promoting [55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62], denitrification [54] as well as bio- and phytoremediation [54, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67] traits, could be complemented by the selenite-to-Se0 reduction capabilities potentially applicable to moderately selenium-contaminated soils.

This study has provided for the first time some experimental evidence that in the ubiquitous and widely studied rhizobacterium Azospirillum brasilense Sp7, the reduction (and therefore detoxification) of selenite ions occurs with the possible involvement of one of the denitrification pathway enzymes, nitrite reductase. It has also been found that the most widely recognised mechanism of selenite reduction in bacteria, which involves the glutathione (GSH) redox system, is not likely to play any significant role in A.brasilense Sp7. Since there has yet been obtained no direct proof that nitrite reductase is the only enzyme responsible for selenite reduction in A.brasilense (note that the involvement of several parallel selenite reduction pathways is regarded to be possible in some bacteria [44, 84]), this is one of important questions which remains to be further studied.

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Conceptualization, AVT, PVM, AAK; methodology, PVM, AAV, LPP, AVS; software, AVT; validation, AVT, AVS, AAK; formal analysis, AVT, AAK; investigation, PVM, AAV, LPP; resources, AVT, AVS, AAK; data curation, AVT, AAK; writing–original draft preparation, AVT, PVM, AAV; writing–review and editing, AAK; visualization, AVT, PVM, AAV; project administration, AVT; funding acquisition, AVT. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work to take public responsibility for appropriate portions of the content and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring its accuracy or integrity. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript, have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

According to Russia’s local regulations, this study does not require Ethics Committee or Institutional Review Board approval because it does not involve human or animal subjects.

Some of the experiments were performed on the equipment of the “Simbioz” Centre for the Collective Use of Research Equipment in the field of physical–chemical biology and nanobiotechnology at IBPPM RAS, Saratov, Russia (transmission electron microscope Libra-120). The authors are grateful to Dr. A.M. Burov (this Institute, Saratov, Russia) for his help in carrying out the transmission electron microscopic measurements.

This research was funded in part by The Russian Science Foundation (grant # 23-24-00582). The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to submit the article for publication.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.