Hyperhomocysteinemia induces stress response in endoplasmic reticulum (ERS). Here, we tested whether blockage of homocysteine (Hcy) induced ERS and subsequent apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells can be inhibited by blockage of PERK/eIF2α/ATF4/CHOP signaling. Short-term exposure of vascular smooth muscle cells to Hcy led to the phosphorylation of PERK (pPERK), which in turn, phosphorylated eIF2 alpha (peIF2α) and inhibited the unfolded protein response. Long-term Hcy exposure, however, increased the expression of ATF-4 and CHOP and led to apoptosis. Treatment of cells with salubrinal, a specific inhibitor for eIF2α decreased the expression of ATF-4 and CHOP, and prevented apoptosis. Together, the results show that PERK pathway is involved in Hcy-induced vascular smooth muscle cell apoptosis and that blocking the PERK pathway protects against this injury.

Vascular disease is one of leading causes of mortality worldwide (1-3). Hyperhomocysteinemia (HHcy), which results from elevated homocysteine (Hcy) level, has been recognized as an independent risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease and its complications (4-5). Vascular damage caused by HHcy is associated with the breakdown of the extracellular matrix (ECM), causing increased deposition of collagen that results in vessel stiffness (6-7). Numerous studies have indicated that prolonged exposure of cells to HHcy results in programmed cell death, which aggravates the extent of the vascular damage (8-10).

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER) is an organelle essential for protein modification, protein folding and calcium storage. Accumulation of misfolded proteins or imbalance of Ca2+ leads to ER stress (ERS). During ERS, three transmembrane proteins, protein kinase-like ER kinase (PERK), inositol-requiring kinase 1 (IRE1), and transcription factor-activating transcription factor 6 (ATF6), are activated and trigger an adaptive response (11-12). The N-termini of these unfolded protein response (UPR) receptors are located in the lumen of the ER, and their C-termini protrude into the cytoplasm, connecting ER to the cytoplasm. When PERK, IRE1 and ATF6 are inactive, their N-termini bind to GRP78, a marker of ERS. However, when unfolded proteins accumulate in the ER, GRP78 dissociates from these molecules and subsequently triggers UPR. Phosphorylation of PERK results in phosphorylation of the α subunit of eukaryotic initiation factor 2 (eIF2α), leading to the inhibition of protein synthesis (13-15).

Activating transcription factor 4 (ATF4) is a bZIP transcription factor that is frequently upregulated during stress in cells. ATF4 controls the expression of a wide range of adaptive genes involved in amino acid transport and metabolism that allow cells to endure stress (16-17). However, under persistent stress conditions, ATF4 induces cell-cycle arrest, senescence or even apoptosis (18-19). Unlike most proteins, ATF4 is not inhibited by the phosphorylation of eIF2α during ERS. Activation of ATF4 leads to the induction of C/EBP homologous protein (CHOP), which is associated with the increased ERS induced apoptosis (20).

Typically, eukaryotic cells undergo apoptosis either through and intrinsic or an extrinsic pathway. Apoptosis induced by extrinsic pathway involves the activation of caspases which results from the binding of tumor necrosis factor α to its receptor, tumor necrosis factor receptor α (TNF-R α)(21). On the other hand, during the extrinsic pathway, Bcl-2 proteins mediates cytochrome C release from mitochondria to cytosol, which in turn, leads to activation of caspases and apoptosis (22).

HHcy increases the expressions of both GRP78 and GRP94 in various cell types including vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) (23-24) suggesting that these cells are susceptible to ERS and apoptosis. In this work, we tested whether Hhcy leads to ERS and apoptosis and whether these processes are mediated by the PERK signal pathway. The findings lend support to the view that Hcy-induces apoptosis in vascular smooth muscle cells and that blocking the PERK pathway protects against this injury.

DL-homocysteine and salubrinal were obtained from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA). Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM), trypsin-EDTA and fetal bovine serum (FBS) were purchased from Gibco Technologies (Logan, UT, USA). Antibodies against GRP78 (ab21685) and GRP94 (ab18055) were purchased from Abcam (Boston, MA, USA). Antibodies against PERK (3192s), p-PERK (3179s), eIF2a (5324s), p-eIF2a (3597s), ATF4 (11815S), CHOP (2895s), cytochrome c (4280), TNF-α (6945) and β-actin (12262s) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology (Boston, MA, USA). Electrochemiluminescence (ECL) Western blotting detection reagents were obtained from Millipore (Bedford, MA, USA). Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and LDH Assay Kits were purchased from Beyotime (Jiangsu, China). A TUNEL Apoptosis Detection Kit III was purchased from Boster (Wuhan, China). Total RNA Isolation Kit and Revert Aid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit were purchased from TAKARA (Dalian, China).

Mouse aortic VSMCs (MOVAS cells) were purchased from the Cell Line Bank of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). MOVAS cells were cultured in DMEM containing 15% FBS, 100 U/mL penicillin and 100 µg/mL streptomycin at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 environment. Cells that had grown to 80% confluence were used for the following treatments. Some cells were exposed to a medium containing 5 mmol/L Hcy for 0, 6, 12, 24 36 or 48 h. Other cells were pretreated with 20 µmol/L salubrinal for 30 min and then cells were exposed to a single dose of 5 mmol/L Hcy for 48h.

CCK-8 assay was used to measure cell viability. MOVAS cells were seeded in 96-well plates. After cultured for 6 to 24 h, cells were subjected to various treatments. The cell medium from each well was replaced with 200 µL of fresh culture medium plus 20 µL of CCK-8 solution, and the cells were incubated for 80 min at 37 °C. A microplate absorbance reader (Bio-Rad) was used to measure the absorbance at a wavelength of 450 nm. Lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) is a key enzyme in the conversion of pyruvate to lactate under anaerobic conditions (25). The leakage of LDH is an important index of cell membrane damage, which often leads to the necrotic cell death (26). Cell culture medium is collected for detection of LDH after hcy treatment. The extent of LDH that leaked from damaged cells was assessed at 450 nm by colorimetric detection.

At 70–80% confluence, the MOVAS cells transferred to a 60 mm culture dish and washed three times with 1 x PBS. Cells were fixed in cold 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min and washed three times with 1 x PBS for 5 min per wash. Cells were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Nonspecific binding was blocked with serum from the same host as that of the secondary antibody for 30 min. Cells were incubated with primary antibodies (1:200 dilution) at 4 °C for 14–18 h, washed and then incubated with secondary antibodies (1:500 dilution) at room temperature for 2 h (in the dark). After three washes with PBS, cells were stained with DAPI and sealed with glycerin.

Cells were collected after being washed with ice-cold PBS and were then lysed in RIPA lysis buffer containing PMSF (1:100) for 30 min on ice. After centrifugation at 12000 ×g for 3 min at 4 °C, the supernatants were collected for determination of the protein concentration using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit. Supernatants were mixed with Laemmli loading buffer at a 4:1 ratio, and the mixtures were then boiled at 100 °C for 10 min. Extraction of cytosolic proteins was performed according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Protein samples were separated by gel electrophoresis and transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membrane. Membranes were blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk dissolved in Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20 (TBST) for 2 h at room temperature. After incubation with primary antibodies (1:1000 dilution) at 4 °C for 14 h, membranes were incubated with secondary antibodies (1:3000 dilution) for 2 h at room temperature. An ECL detection kit was used to scan the bands, and Image Lab software was used to collect and analyze the data.

Total RNAs were isolated with the RNA Isolation Kit, and first-strand cDNA was synthesized using RevertAid First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit. The qPCR amplification reactions were performed with Maxima SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix. GAPDH served as an internal control. Three replicate samples were processed at each time point. Relative quantification was performed using the 2-∆C C T method. RT-PCR primers (Sangong, Shanghai, China) are listed in Table 1.

| Gene | Forward primer 5′- 3’ | Reverse primer 5′- 3’ |

|---|---|---|

| GRP94 | CAGTTGGATGGGTTAAACGCA | CAGTTGGATGGGTTAAACGCA |

| Hspa5 | AGC GAC AAG CAA CCA AAG AT | AGC GAC AAG CAA CCA AAG AT |

| GAPDH | TGT GTC CGT CGT GGA TCT GA | TGT GTC CGT CGT GGA TCT GA |

Apoptosis was detected in MOVAS cells by using terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling (TUNEL) assay kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, after treatments, the MOVAS cells were incubated with TdT and fluorescein-labeled dUTP for 45 min at 37 °C, followed by incubation with staining with DAPI to label the nuclei and photography using a confocal microscope (Olympus FluoView 2000). To calculate the percentage of apoptotic cells, five random fields were counted for each of the five groups.

The results are presented as the mean ± SD. The data were analyzed via one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s test or Student’s t-test using Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 13.0 software. A p value of < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant.

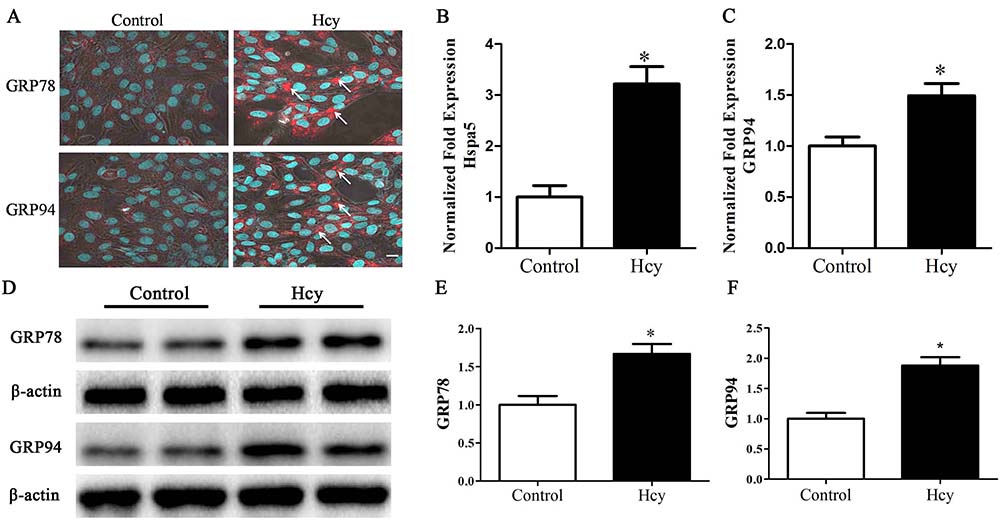

Upon accumulation of unfolded proteins in the ER, the ER stress chaperones, HSPA5 (GRP78) and GRP94 dissociate from these unfolded proteins and subsequently trigger UPR. The treatment of MOVAS cells by Hcy respectively, increased, by about 3.22 and 1.49 folds, the levels of mRNAs of HSPA5 and PDIA3, an essential redox-sensitive activator of PERK (figure 1B-C). The increased expressions of ER stress chaperones, GRP78 and GRP94 were detected by immunofluorescence staining and Western blotting (figure 1A, 1D-F).

Figure 1

Figure 1Cells were treated with 5.0 mmol/L Hcy for 12 h. A. immunofluorescence staining of GRP78 and GRP94. Arrow points to positive cells. Scale bar, 10 µm. B-C. Quantitative RT-PCR of Hspa5 and GRP94. D-F. Western blotting of GRP78 and GRP94. *p< 0.05 versus the control (0 hr).

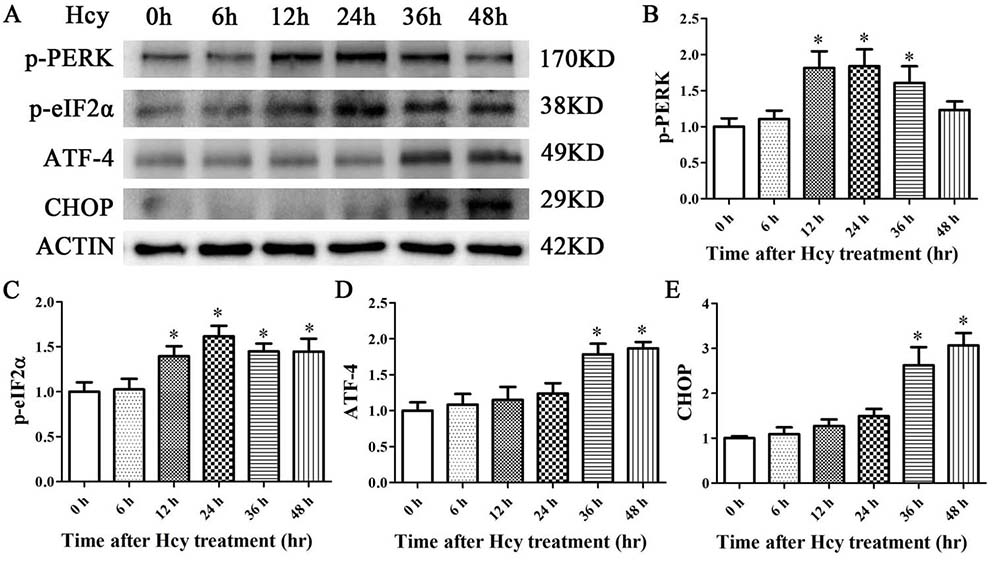

To decipher whether Hcy signals through PERK in VSMCs, MOVAS cells were treated with Hcy (5 mmol/L) for up to 48 hr (27). After 12 hr, the treatment led to increased expression of phosphorylated PERK (pPERK) and its downstream effector molecule, eIF2α (peIF2) (figure 2A-E). These levels continued to persist and then fell at 36 to 48 hr (figure 2A-E).

Figure 2

Figure 2The expression levels of p-PERK, p-eIF2α, ATF4, and CHOP were determined via Western blot analysis. β-Actin was selected as the loading control. The data are presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments. *p< 0.05 versus the control (0 hr).

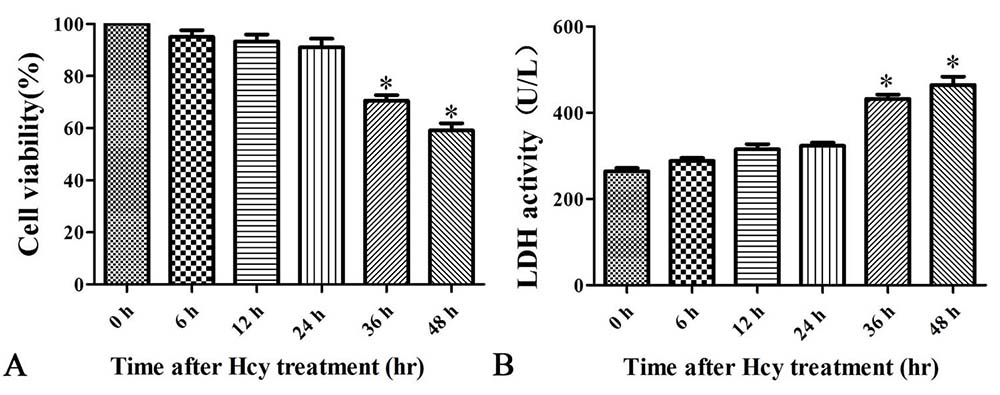

To decipher whether Hcy is cytotoxic to VSMCs, MOVAS cells were treated with Hcy (5 mmol/L) for up to 48 hr (27). Consistent with causing damage, Hcy increased the extracellular level of LDH enzyme activity in a time-dependent manner (Figure 3B). Cell viability also progressively decreased reaching 59.13% at 48 hr (Figure 3A).

Figure 3

Figure 3Cells were treated with 5.0 mmol/L Hcy for 0, 6, 12, 24, or 48 h. A. Cell viability assessed by CCK-8 assay. B. LDH enzyme activity. The data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. *p< 0.05 versus the control (0 hr).

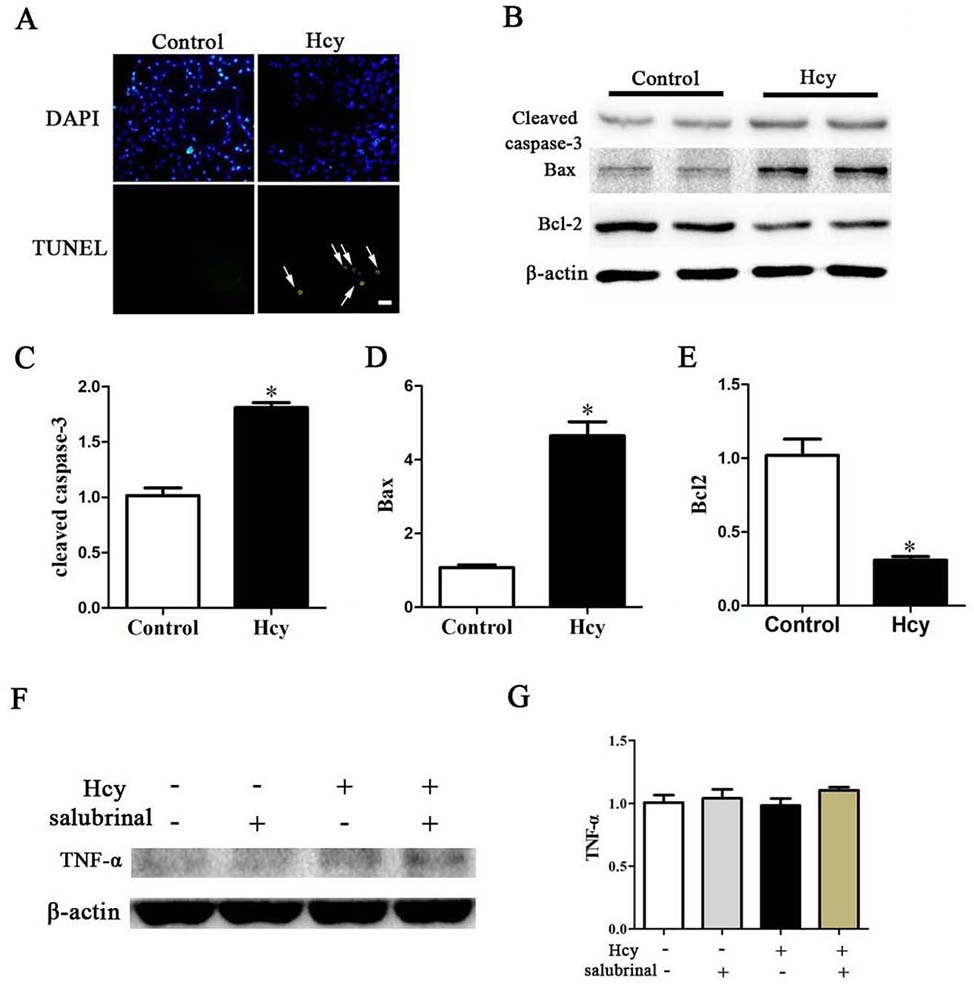

Both Bax and Bcl-2 are apoptosis-related factors that play a critical role in apoptosis by activation of caspase-3 (28-29). Hcy treatment also led to a significantly decreased the Bcl-2 levels which protects cells from apoptosis and increased Bax which activates caspase and apoptosis (Figure 4B, 4D-E). Consistent with such results, treatment of MOVAS cells with Hcy also significantly increased the activity of cleaved caspase-3 and the percentage of TUNEL+ apoptotic cells (Figure 4A-C). Treatment of cells with Hcy, however, did not change the expression of TNF-α (Figure 4F-G).

Figure 4

Figure 4A. TUNEL stained MOVAS cells. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Arrow points to apoptotic cells. Scale bar, 20 µm. B. Western blotting of Cleaved Caspase-3, Bcl-2, Bax, TNF-α and ACTIN *p< 0.05 versus the control (0 hr).

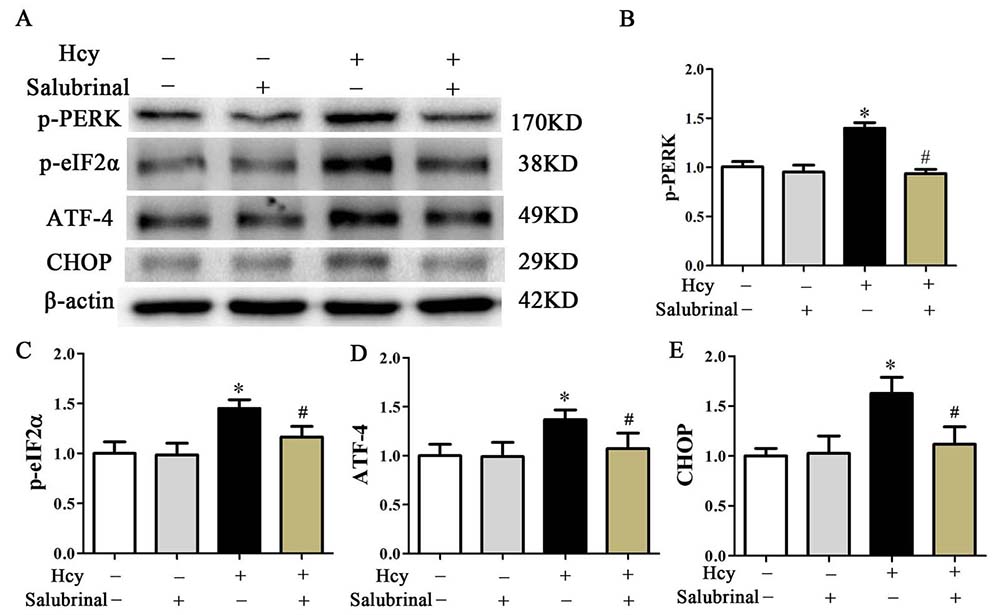

To further confirm the role of the PERK pathway in Hcy-induced apoptosis, salubrinal, a specific inhibitor for eIF2α dephosphorylation (30) was employed to block the PERK signaling pathway. While MOVAS cells that were incubated with Hcy (5 mmol/L) for 48 hr showed increased p-eIF2α and ATF4 expression, pretreatment with salubrinal (20 μmol/L) for 30 min blocked these responses and also blocked the Hcy mediated increase in CHOP (Figure 5A-D).

Figure 5

Figure 5Western blot analysis of p-PERK, p-eIF2α, ATF4, and CHOP. β-actin was used as the loading control. Data are presented as the mean ± SD from three independent experiments. *p< 0.05 versus the control (0 hr). #p< 0.05 versus the Hcy group.

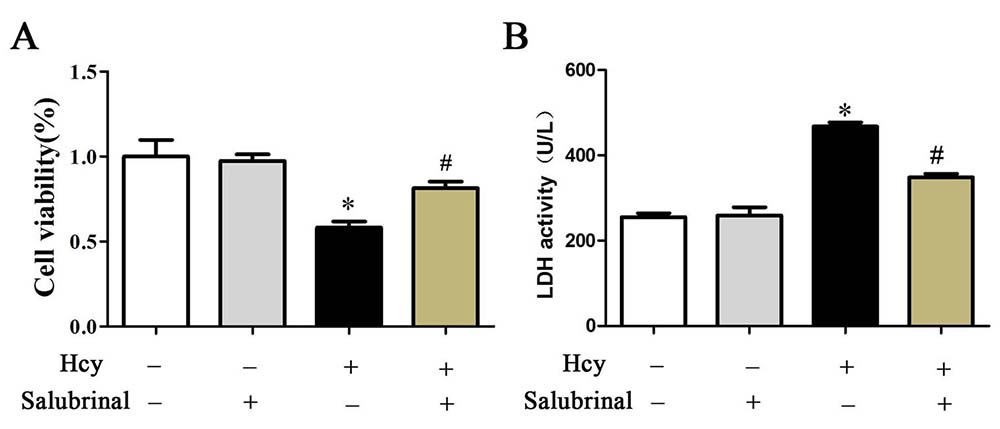

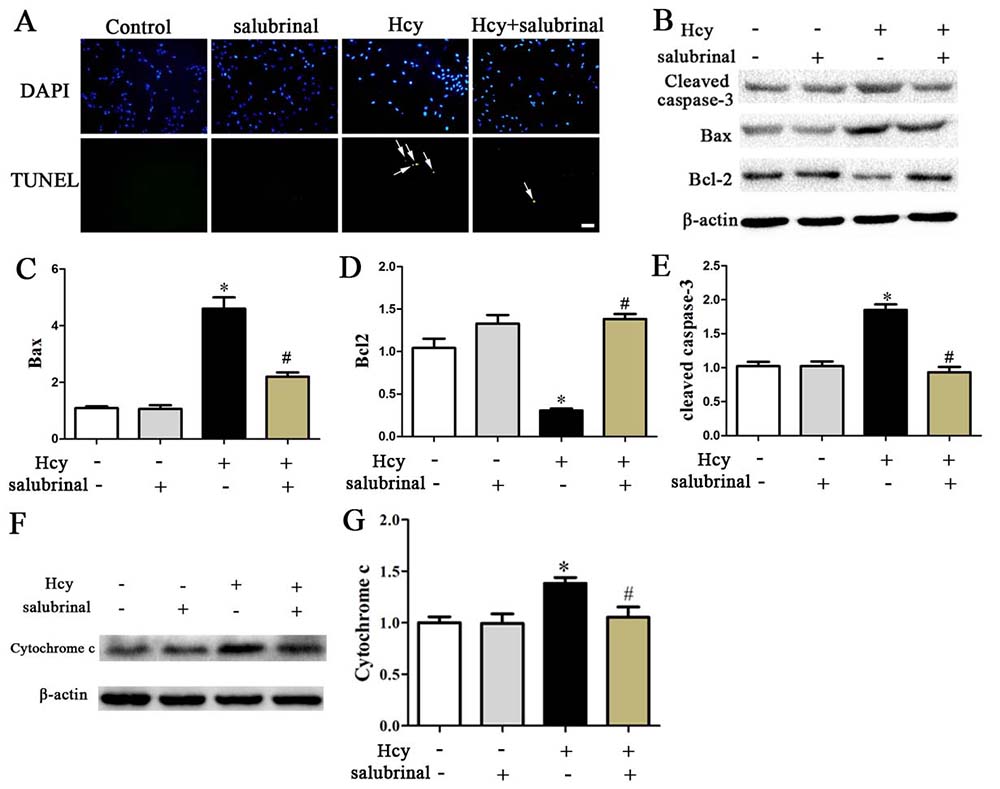

Inhibition of PERK signaling by salubrinal blocked cell damage as evidenced by increased expression of Bcl-2 and decreased expression of Cytochrome c, Bax, cleaved caspase-3, and decreased the extracellular release of LDH (Figure 6B, Figure 7B-E). This inhibition also prevented the decrease in cell viability and the increase in the number of TUNEL+ apoptotic cells that were inducible by Hcy treatment (Figure 6A, 7A).

Figure 6

Figure 6A. Cell viability was determined by CCK-8 assay. B. The LDH enzyme activity in culture medium was determined by LDH content kit. The results are expressed as the means ± SD of three independent experiments. *p< 0.05 versus the control (0 hr). #p< 0.05 versus the Hcy group.

Figure 7

Figure 7A. TUNEL stained MOVAS cells. Nuclei were stained with DAPI. Scale bar: 20 µm. B-E. Western blotting of Cleaved Caspase-3, Bcl-2, Bax, Cytochrome C. β-actin was used as the loading control. *p< 0.05 versus the control (0 hr).

HHcy is an independent risk factor for the development of vascular disease (31-32). Derangements in the metabolism of methionine and/or Hcy leads to the rise of intracellular Hcy and subsequently to the leakage of a large amount of Hcy to the surrounding tissues. The concentration of Hcy in tissues and plasma rises with age, and over time, high levels of Hcy causes vascular damage with numerous complications (33). HHcy is associated with the breakdown of the extracellular matrix (ECM), which, ultimately, through increased deposition of collagen results in vessel stiffness (5-7).

Hcy also induces NO depletion, oxidative stress, and ERS (5-7). One candidate for the Hcy inducible ERS is the PERK signaling pathway which is involved in the development of cerebro-vascular disease (34). In mammalian cells, PERK is a key molecule that regulates UPR-related signal transduction pathways. Activation of PERK signaling pathway induces the phosphorylation of eIF2α (peIF2α), which in turn, inhibits protein synthesis and enhances the ER protein-folding capacity. However, chronic PERK signaling leads to upregulation of ATF4 and CHOP expression (35). Under normal conditions, ATF4 allows cells to endure stress, however, under persistent stress conditions, ATF4 induces cell-cycle arrest, senescence or even apoptosis (16-19). CHOP, on the other hand, is a mediator of apoptosis induced by ERS. Increased CHOP promotes the expression of BH3-only proteins, Bim and Bax. The transfer of Bax proteins to the mitochondria, leads to the activation of caspase-3 and apoptosis (36-37). The studies carried out here show that in VSMCs, Hcy significantly increases the expression of GRP78 and GRP94 and while it activates p-PERK and p-eIF2a, it does not not increase CHOP expression. However, prolonged Hcy treatment enhances the expression of both ATF-4 and CHOP and significantly increases the rate of apoptosis in VSMCs. Lack of changes in TNF-α levels by Hcy and induced changes in expression of Bcl-2, Cytochrome c, and BAX are consistent with CHOP mediated ERS induced apoptosis likely by promoting mitochondrial outer membrane permeablization (38).

One rationle for prevention of Hcy mediated vascular damage is to block ERS and subsequent apoptosis in VSMCs. Hcy induces ERS through PERK signaling. It has been shown that salubrinal, which is a selective inhibitor for eIF2a dephosphorylation affords protection against ERS (39). As shown here, blocking the PERK signaling pathway in VSMCs by salubrinal decreased CHOP protein expression, increased cell viability and decreased VSMCs apoptosis. Together, these findings confirm that VSMCs can be protected from Hcy induced ERS and subsequent apoptosis by blocking the PERK signaling pathway.

HHcy

Hyperhomocysteinemia

homocysteine

extracellular matrix

endoplasmic reticulum

ER stress

protein kinase-like ER kinase

inositol-requiring kinase 1

transcription factor-activating transcription factor 6

unfolded protein response

eukaryotic initiation factor 2

transcription factor 4

C/EBP homologous protein

vascular smooth muscle cells

Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium

Cell Counting Kit-8

Mouse aortic VSMCs

bicinchoninic acid

transferred to a polyvinylidene fluoride

Tris-buffered saline containing Tween 20

transferase-mediated dUTP nick end-labeling

Social Sciences

Lactate dehydrogenase