1 Department of Gynecology, Women’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, 310006 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm that can occur in a wide range of anatomical locations. Fat-forming SFT is a rare morphological variant of SFT characterized by an additional adipocyte component and a clinical course ranging from benign to overtly malignant.

We report the case of a 65-year-old gynecologic patient presenting with a large mass in the left adnexal region, which was found during surgery to originate from the retroperitoneal area. Histological and immunohistochemical (IHC) analyses revealed dense spindle cells that were positive for cluster of differentiation 34 (CD34), cluster of differentiation 99 (CD99), B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6). Together with the presence of S-100-positive adipocytes within the tumor, the IHC results confirmed the diagnosis of fat-forming SFT. The patient showed no signs of recurrence or metastasis 24 months after surgery, and lifelong follow-up was planned.

Although fat-forming SFT is very rare in gynecology, this diagnosis should be considered whenever a large pelvic or retroperitoneal mass is identified prior to surgical intervention.

Keywords

- solitary fibrous tumor

- fat-forming solitary fibrous tumor

- surgical treatment

First reported by Klemperer and Coleman in 1931, solitary fibrous tumor (SFT) is a rare mesenchymal neoplasm that was initially described in the pleura and subsequently in many extra-pleural locations [1]. Fat-forming SFT is classified as a rare variant of SFT according to the 2013 World Health Organization (WHO) classification of “tumors of soft tissue and bone tumors”, as well as in the more recent 2020 classification. It is characterized pathologically by a prominent hemangiopericytomatous vasculature interspersed with mature adipocytes within the tumor, and can exhibit a clinical course ranging from benign to frankly malignant [2, 3]. Most tumor lesions present clinically as deep-seated, long-standing, indolent tumors discovered fortuitously during the medical examination of patients, whereas others present with symptoms of compression related to mass or pressure effects on adjacent structures. Radiologically, the classical features of fat-forming SFTs are large, well-defined, lobulated, solid, and vascular masses that displace neighboring structures. Fat-forming SFTs exhibit a wide anatomical distribution, with the most common sites being the lower extremities including thigh, hip, calf, popliteal fossa, perineum, inguina and male external genitalia, followed by the retroperitoneal area. However, the exact origin and position of tumors may show some deviation before surgical confirmation. Here, we report a case of fat-forming SFT in the field of gynecology. A 65-year-old gynecological patient presented with a large lesion mass located in the left adnexal area in preoperative imaging. During surgical treatment, the mass was found to originate in the retroperitoneal area. A total of 67 cases of benign fat-forming SFT and 16 cases of malignant fat-forming SFT have been reported in the English literature since the initial description of this tumor type (Table 1, Ref. [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40] and Table 2, Ref. [41, 42, 43]). In this article, we review the clinical presentation of these cases and discuss the clinical and imaging results, pathological features, immunohistochemical (IHC) staining, molecular biological characteristics, and management of this rare tumor type. The fat-forming SFT cases reported to date were not specifically related to gynecology. However, this rare tumor variant should still be included in the differential diagnosis when hypervascular components are observed in addition to fatty components in the field of gynecology.

| Case | Age (years) | Sex | Site | Size (cm) | Follow-up (months) | CD34 | CD99 | BCL-2 | STAT6 | Reference information | Ref. |

| 1 | 44 | F | Sinonasal area | 7.0 | NED/48 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Nielsen et al., 1995 | [4] |

| 2 | 56 | M | Posterior shoulder | 4.0 | NED/4 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 3 | 72 | M | Retroperitoneum | 10.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 4 | 41 | F | Thigh | 9.0 | NED/13 | + | NA | NA | NA | Ceballos et al., 1999 | [5] |

| 5 | 51 | M | Calf | 3.0 | NED/36 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Folpe et al., 1999 | [6] |

| 6 | 74 | M | Pelvic | 9.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 7 | 53 | M | Retroperitoneum | NA | NED/84 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 8 | 33 | M | Retroperitoneum | 18.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 9 | 72 | M | Supraclavicular | NA | NED/60 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 10 | 61 | M | Pelvic | 12.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 11 | 49 | F | Submandibular | 5.0 | NED/36 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 12 | 33 | M | Thigh | 6.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 13 | 49 | F | Thigh | 13.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 14 | 60 | M | Thigh | 21.0 | NED/48 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 15 | 39 | F | Calf | 4.0 | NED/36 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 16 | 60 | M | Spine | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 17 | 51 | M | Thigh | 17.0 | NED/24 | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 18 | 64 | M | Pleural | 6.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 19 | 63 | M | Inguinal | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 20 | 74 | F | Hip | 8.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 21 | 54 | M | Retroperitoneum | 7.5 | NED/72 | – | + | + | NA | Guillou et al., 2000 | [7] |

| 22 | 42 | F | Mediastinum | 2.5 | NED/36 | + | + | + | NA | ||

| 23 | 68 | F | Hip | 1.7 | NA | + | + | + | NA | ||

| 24 | 33 | M | Hip | 4.5 | NED/14 | + | + | – | NA | ||

| 25 | 48 | M | Elbow | 5.0 | NA | – | + | + | NA | ||

| 26 | 39 | F | Thigh | 10.0 | NED/22 | + | + | – | NA | ||

| 27 | 27 | F | Neck | 5.5 | NED/12 | + | + | + | NA | ||

| 28 | 43 | F | Iliac fossa | 5.5 | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | ||

| 29 | 75 | F | Epicardium | 4.5 | NED/60 | + | + | – | NA | ||

| 30 | 67 | F | Popliteal fossa | 9.0 | NED/6 | + | + | + | NA | ||

| 31 | 46 | M | Retroperitoneum | 19.0 | NED/6 | + | + | – | NA | ||

| 32 | 53 | M | Orbit | 2.0 | NED/77 | – | + | – | NA | ||

| 33 | 51 | M | Retroperitoneum | 18.0 | NED/6 | + | + | + | NA | ||

| 34 | 65 | M | Orbit | 3.5 | NED/48 | + | NA | NA | NA | Davies et al., 2002 | [8] |

| 35 | 36 | M | Thyroid | 6.0 | NED/25 | + | + | + | NA | Cameselle et al., 2003 | [9] |

| 36 | 51 | F | Thigh | 5.0 | NED/24 | + | + | NA | NA | Domanski, 2003 | [10] |

| 37 | 56 | M | Retroperitoneum | 3.0 | NED/12 | – | + | NA | NA | ||

| 38 | 55 | F | Neck | 10.0 | NED/12 | + | + | + | NA | Alrawi et al., 2004 | [11] |

| 39 | 51 | F | Retroperitoneum (Kidney) | 10.0 | NA | + | + | + | NA | Yamaguchi et al., 2005 | [12] |

| 40 | 79 | F | Axilla | 9.0 | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | Verfaillie et al., 2005 | [13] |

| 41 | 39 | M | Mediastinum | 6.5 | NED/12 | + | NA | NA | NA | Amonkar et al., 2006 | [14] |

| 42 | 36 | F | Skull | 5.0 | NED/12 | NA | NA | NA | NA | Shaia et al., 2006 | [15] |

| 43 | 61 | M | Mediastinum | 9.5 | NED/28 | + | + | + | NA | Liu et al., 2007 | [16] |

| 44 | 54 | M | Lung | 4.0 | NA | – | NA | + | NA | Yamazaki and Eyden, 2007 | [17] |

| 45 | 43 | M | Perineum | 5.5 | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | Kim et al., 2009 | [18] |

| 46 | 49 | F | Orbit | 3.5 | NA | + | + | + | NA | Pitchamuthu et al., 2009 | [19] |

| 47 | 21 | M | Pelvic | 18.0 | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Dozois et al., 2009 | [20] |

| 48 | 38 | M | Spine | NA | NED/6 | – | + | + | NA | Aftab et al., 2010 | [21] |

| 49 | 74 | M | Pleural | 13.0 | NED/14 | + | + | + | NA | Park et al., 2011 | [22] |

| 50 | 56 | F | Stomach | 0.8 | NED/12 | + | + | + | NA | Jing et al., 2011 | [23] |

| 51 | 26 | M | Paratesticular | 6.0 | NA | + | NA | + | NA | Barazani and Tareen, 2012 | [24] |

| 52 | 33 | M | Parotid | 2.0 | NED/12 | + | + | + | NA | Chen et al., 2013 | [25] |

| 53 | 64 | M | Retroperitoneum (Kidney) | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | Cortes et al., 2014 | [26] |

| 54 | 51 | M | Skull | 3.0 | NA | – | + | + | NA | Esquenazi et al., 2014 | [27] |

| 55 | 30 | F | Retroperitoneum (Kidney) | 6.0 | NED/19 | + | + | + | NA | Chen et al., 2015 | [28] |

| 56 | 11 | F | Submandibular | 6.0 | NED/12 | + | – | – | NA | Madala et al., 2015 | [29] |

| 57 | 37 | M | Pleural | 6.0 | NED/6 | + | NA | NA | NA | Hui et al., 2015 | [30] |

| 58 | 32 | M | Foot and Ankle | 4.0 | NED/24 | + | + | NA | NA | Pandey et al., 2017 | [31] |

| 59 | 49 | M | Retroperitoneum (Kidney) | 16.0 | NA | + | + | + | NA | Bacalbasa et al., 2018 | [32] |

| 60 | 47 | F | Pleural | 5.0 | NED/13 | + | – | NA | + | Takeda et al., 2019 | [33] |

| 61 | 37 | M | Corpus spongiosum | 6.0 | NED/18 | – | + | + | + | Liu et al., 2019 | [34] |

| 62 | 33 | F | Sacrum | 7.0 | NA | + | NA | + | + | Furuta et al., 2021 | [35] |

| 63 | 51 | F | Breast | 3.5 | NED/7 | + | + | + | + | Liu et al., 2023 | [36] |

| 64 | 53 | M | Sinonasal area | 3.0 | NA | + | + | + | + | Sabater et al., 2022 | [37] |

| 65 | 54 | F | Breast | 4.0 | NED/5 | + | NA | NA | + | Ben et al., 2022 | [38] |

| 66 | 88 | F | Orbit | 5.0 | NED/9 | + | + | + | + | Yao et al., 2024 | [39] |

| 67 | 59 | M | Retroperitoneum | 8.0 | NED/10 | + | NA | NA | + | Ma et al., 2024 | [40] |

SFT, solitary fibrous tumor; CD34, cluster designation 34; CD99, cluster designation 99; BCL-2, B-cell lymphoma 2; STAT6, signal transducer and activator of transcription 6; NED, no evidence of disease; NA, not available; F, female; M, man; Ref, reference. + represents a positive result and – represents a negative result.

| Case | Age (years) | Sex | Site | Size (cm) | Follow-up (months) | CD34 | CD99 | BCL-2 | STAT6 | Reference information | Ref. |

| 1 | 59 | M | Neck | 10.0 | NA | Positive in 11 of 14 cases | Positive in 8 of 10 cases | NA | NA | Lee and Fletcher, 2011 | [41] |

| 2 | 20 | F | Thigh | 11.0 | DOD/57 | NA | NA | ||||

| 3 | 45 | M | Thigh | 11.4 | NED/76 | NA | NA | ||||

| 4 | 62 | M | Scalp | 3.4 | NED/63 | NA | NA | ||||

| 5 | 75 | F | Calf | 9.0 | NED/60 | NA | NA | ||||

| 6 | 41 | F | Posterior thoracic | 5.0 | NED/55 | NA | NA | ||||

| 7 | 87 | F | Liver | 20.0 | DOD/5 | NA | NA | ||||

| 8 | 78 | M | Thigh | 18.0 | NED/30 | NA | NA | ||||

| 9 | 48 | M | Upper arm | 5.8 | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| 10 | 47 | M | Pelvis | 12.0 | NED/38 | NA | NA | ||||

| 11 | 50 | F | Lower back | 5.4 | NED/31 | NA | NA | ||||

| 12 | 75 | F | Vulva | 5.1 | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| 13 | 55 | M | Thigh | 8.2 | NA | NA | NA | ||||

| 14 | 93 | F | Retroperitoneum | 6.0 | NED/8 | NA | NA | ||||

| 15 | 61 | M | Neck | 5.5 | NED/9 | + | + | + | NA | Carvalho et al., 2013 | [42] |

| 16 | 84 | M | Thigh | 11.0 | NED/14 | + | + | + | NA | Noh and Jang, 2014 | [43] |

DOD, died of disease. + represents a positive result.

A 65-year-old postmenopausal woman attended the Women’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University in September 2022. She presented with a large mass in the left adnexal area discovered during an incidental medical examination conducted one month before. The patient had a natural menopause at the age of 56. No significant abnormality was detected in gynecologic ultrasound 4 years prior, no further medical examinations were carried out afterwards, and she did not describe any symptoms related to the mass. She had a vaginal delivery of one child, showed no signs or history of other chronic diseases, and did not drink alcohol, smoke, or use illicit drugs. The patient was 158 cm tall, weighed 55 kg, and had a body mass index of 22.0 kg/m2. Upon physical examination, a soft, deep-seated mass was detected in the left adnexal area. Routine laboratory data, including tumor markers carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), squamous cell carcinoma (SCC), cancer antigen 125 (CA125), cancer antigen 153 (CA153), cancer antigen 199 (CA199) and human epididymis protein 4 (HE4), were within the normal range.

The patient was subjected to standard clinical practice protocol after admission. Transvaginal ultrasound examination revealed the uterus was slightly atrophied and the thickness of the endometrium was about 0.2 cm. A hyperechoic area with abundant blood flow and measuring approximately 11.8

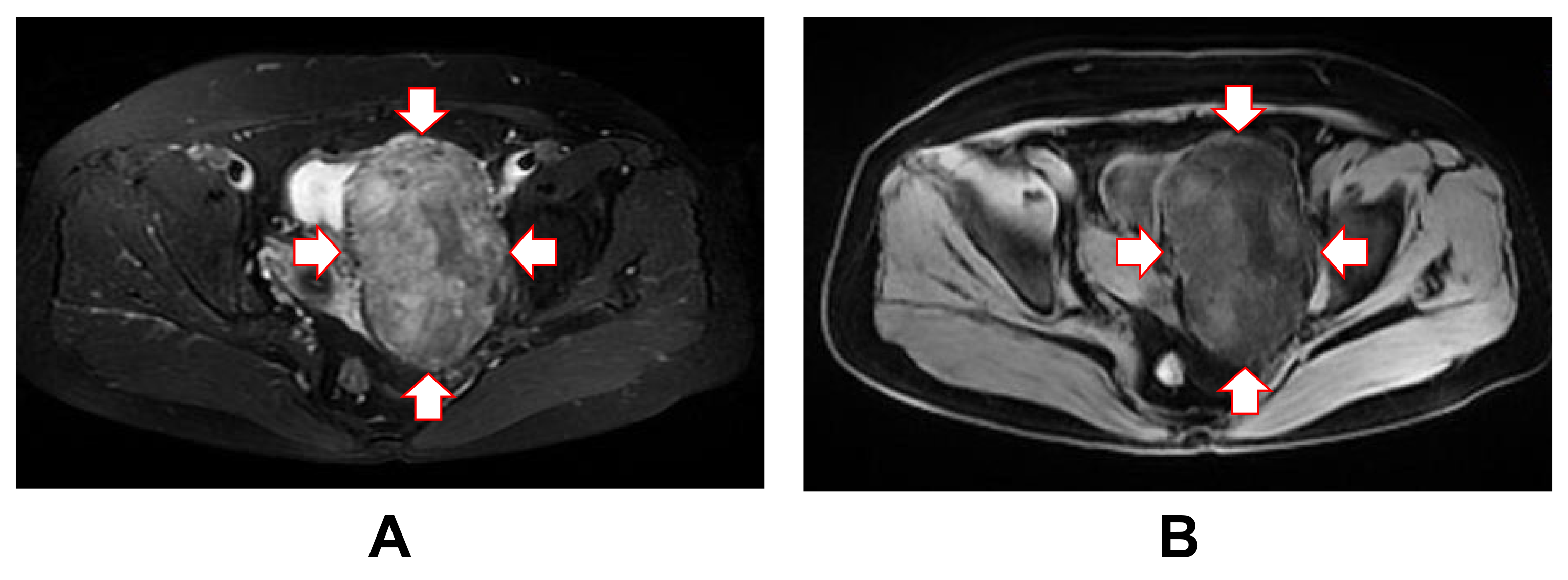

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Magnetic resonance imaging of the lesion mass. Magnetic resonance imaging showing a well-defined, deep mass in the left adnexal area on axial T1-weighted imaging (A) and T2-weighted imaging (B). T1, longitudinal relaxation time; T2, transverse relaxation time. Red arrows mark the boundaries of the tumor mass.

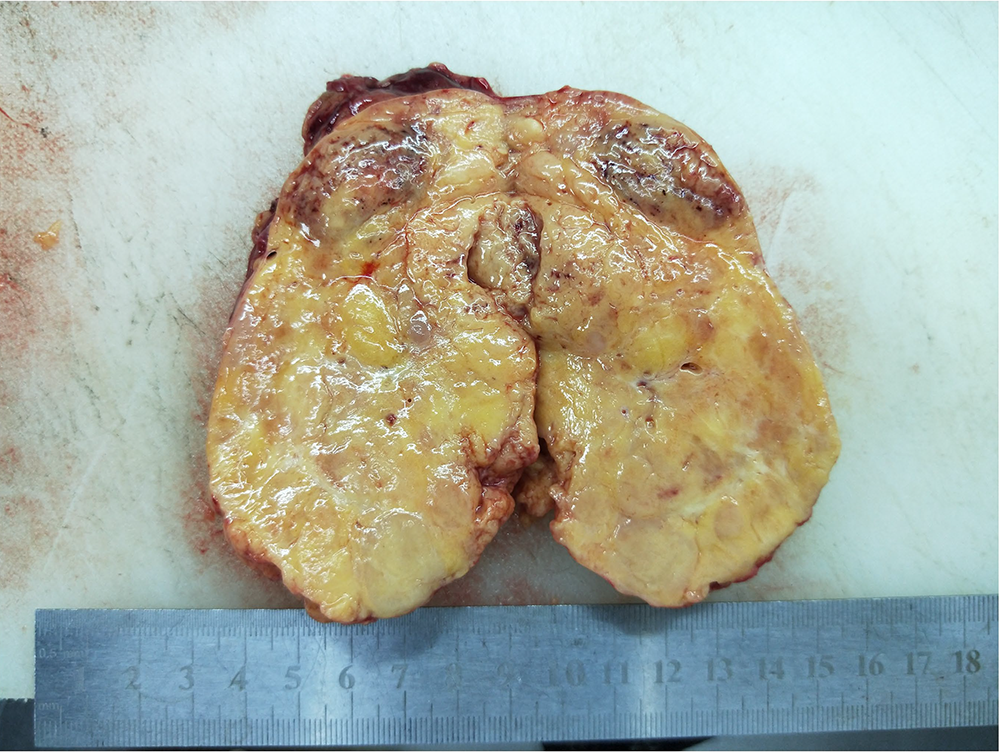

The gross specimen consisted of solid masses of soft tissue and membranous soft tissues measuring 12.0

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Gross examination of the excised tumor specimen. The tumor appeared well-encapsulated and measured 12.0

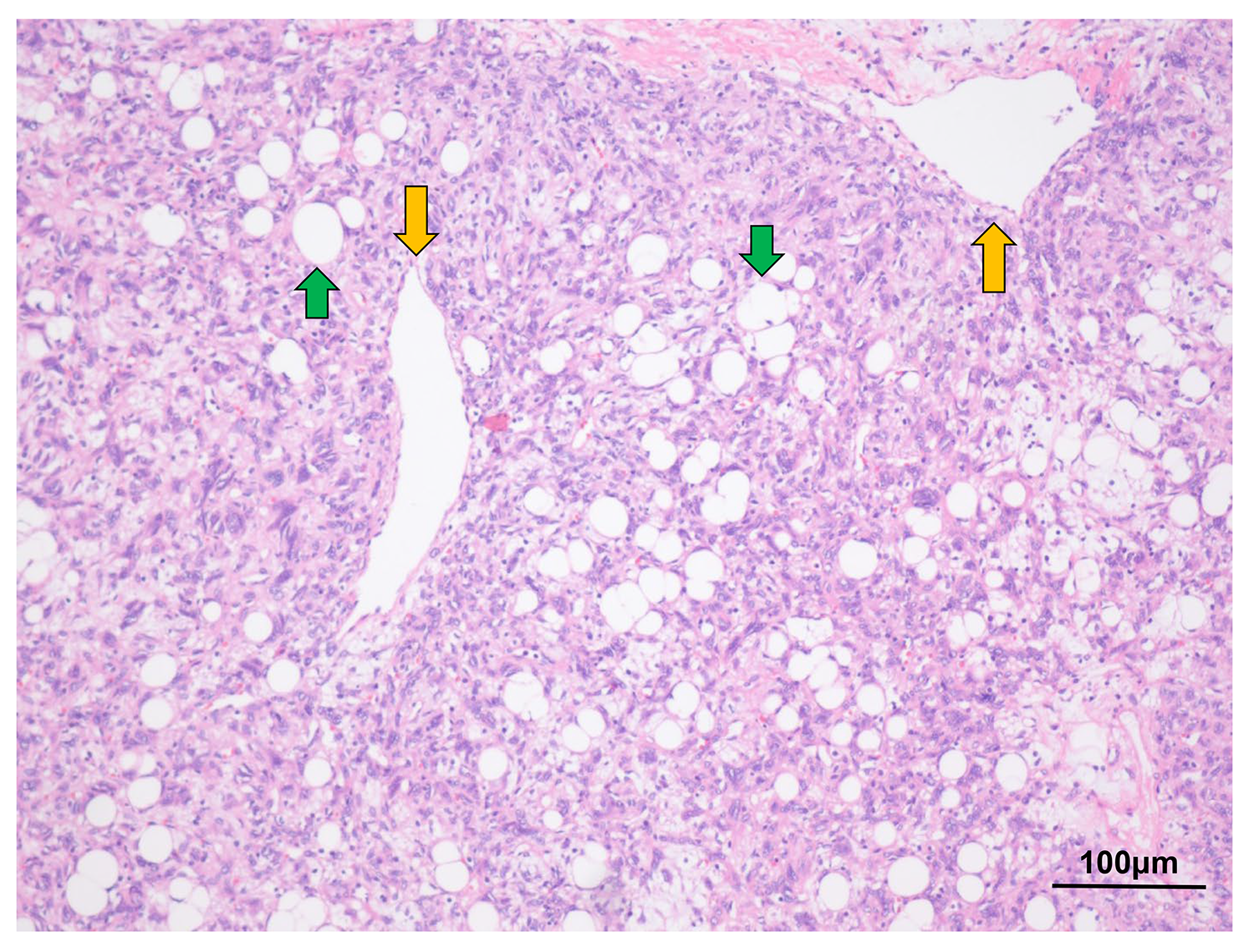

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Hematoxylin and eosin staining of the tumor cells. Hematoxylin and eosin staining revealed the classic histological features of fat-forming SFT, with hemangiopericytomatous vasculature admixed with mature adipocytes (original magnification:

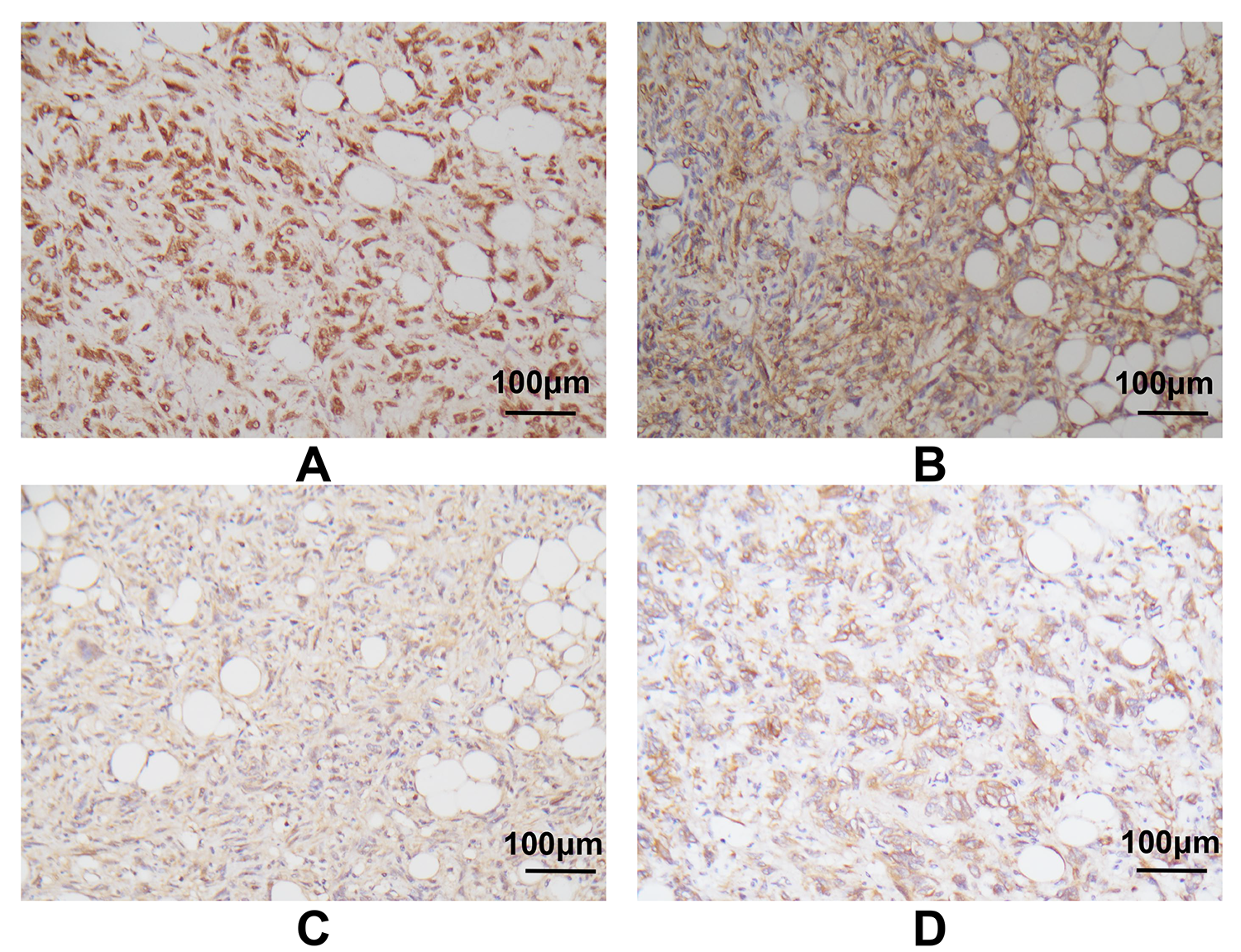

No hemorrhage or necrosis of the tumor was observed. The mitotic count was 1 per 10 high-power field (HPF). IHC was also performed to detect the expression of signal transducer and activator of transcription 6 (STAT6), cluster designation 34 (CD34), cluster designation 99 (CD99) and B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Immunohistochemistry of the tumor cells. Immunohistochemistry indicated strong positivity for STAT6 (A) and CD34 (B), and moderate positivity for CD99 (C) and BCL-2 (D) (original magnification:

After quenching the endogenous peroxidase activity, tissue slides were incubated with blocking serum and then overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against STAT6 (1:50, ab32520, Abcam, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, UK), CD34 (1:2500, ab81289, Abcam, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, UK), CD99 (1:250, ab108297, Abcam, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, UK) and BCL-2 (1:250, ab32124, Abcam, Cambridge, Cambridgeshire, UK). The slides were subsequently incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:1000, 7074, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA) for 1 h at room temperature and then photographed with a microscope. The IHC staining results revealed the tumor cells were strongly and diffusely positive for STAT6, CD34, CD99 and BCL-2, but negative for desmin, smooth muscle actin (SMA), human melanoma black 45 (HMB45), and S-100. Mature adipocytes were positive for S-100, and approximately 10% of tumor cells stained positive for Ki-67. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis was also performed to distinguish the tumor from liposarcoma. Briefly, FISH analysis was performed on the tissue slides following standard protocols and using commercially available probes (F.01017-01, Anbiping, Guangzhou, Guangdong, China) for murine double minute 2 (MDM2, red signal) and a specific probe for centromere 12 (CEP12) as a control (green signal) [44]. A total of 200 interphase nuclei were evaluated in tumor cell-rich areas. The FISH result was negative for amplification of the MDM2 gene in tumor cells (Fig. 5). Based on the above histopathological examination and additional supplementary examinations, a diagnosis of retroperitoneal fat-forming SFT was eventually made.

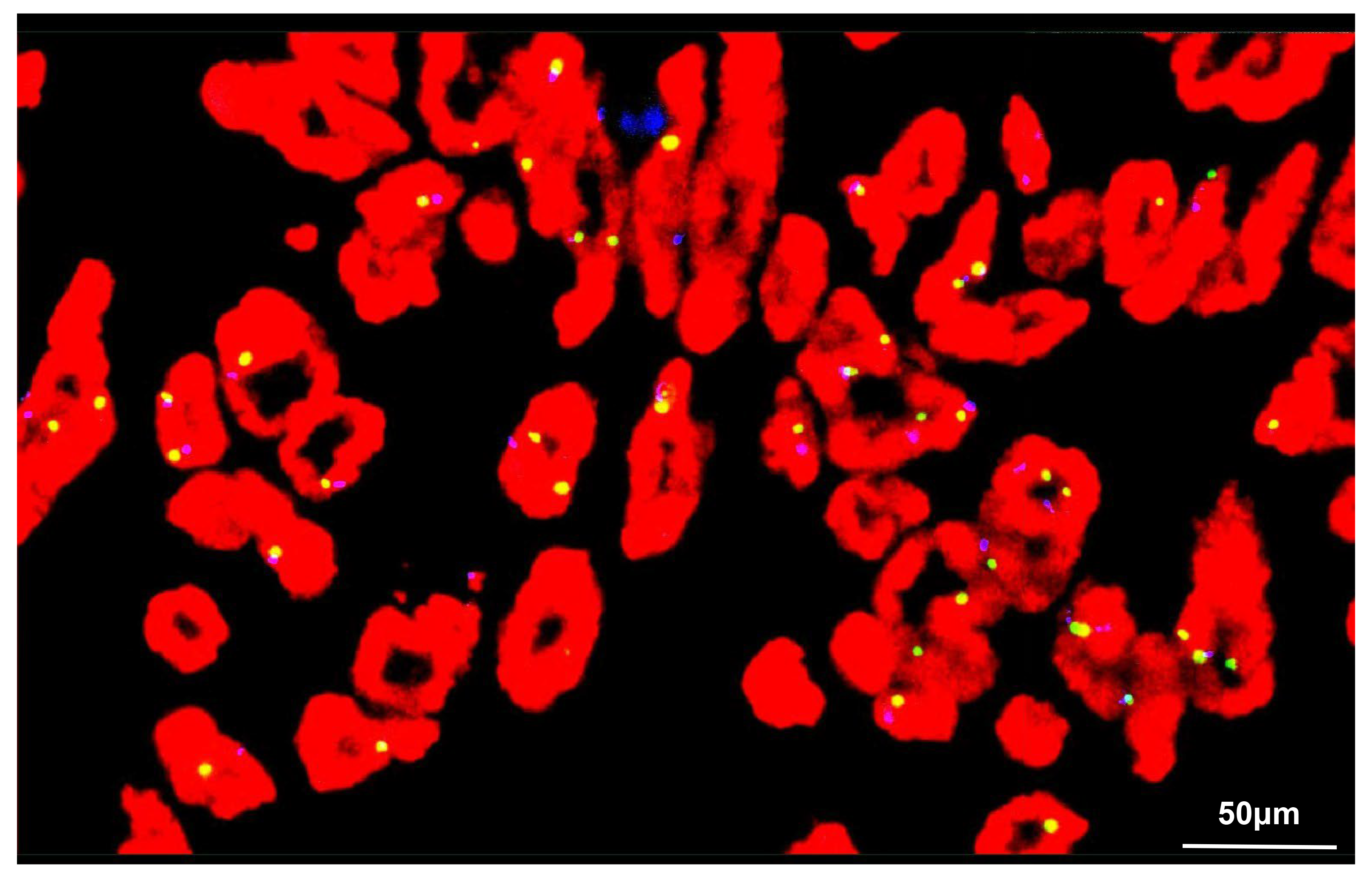

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. FISH analysis of the tumor cells. FISH revealed the total number of MDM2 (red) and CEP12 (green) signals was 193 and 178, respectively. Hence, no amplification of MDM2 was demonstrated in the tumor cells: MDM2/CEP12 = 1.08

No additional treatments such as chemotherapy or radiotherapy were given postoperatively. The patient underwent regular physical examination every 3 months, and laboratory examination including tumor markers, transvaginal ultrasound and abdominal computed tomography (CT) every 6 months. She was in good health 24 months after surgery, with no sign of recurrence or metastasis. Close, long-term follow-up examinations are planned for the patient.

In summary, we present the case of a 65-year-old gynecological patient who underwent surgery for a large adnexal mass found to originate in the retroperitoneal area. This mass was confirmed histopathologically and immunohistochemically to be a fat-forming SFT. The purpose of this article is to report the occurrence of a fat-forming SFT in the field of gynecology. Although this tumor type is very rare, the present findings should be taken into consideration whenever a large pelvic or retroperitoneal mass is presented before surgery.

SFTs have been subclassified into fibrous forms displaying a variety of morphological characteristics rich in collagen fibers, as well as cellular forms that have fewer collagen fibers and are enriched in dendritic vessels. Fat-forming SFT was first described by Nielsen et al. [4] in 1995 as a unique hemangiopericytoma variant and was named lipomatous hemangiopericytoma. In 2000, Guillou et al. [7] reported that lipomatous hemangiopericytomas share similar clinical, pathological, IHC staining patterns and ultrastructural features with SFT, except for the presence of mature adipocytes. These authors suggested that lipomatous hemangiopericytoma does not correspond to a well-defined entity, but instead represents a fat-containing variant of SFT. Eventually, fat-forming SFT was classified as a variant of SFT in the 2013 and 2020 WHO classification of “tumor of soft tissue and bone tumors”.

The etiology of fat-forming SFT is currently not defined, and no risk factors such as tobacco consumption have yet been identified. Fat-forming SFTs exhibit a wide anatomical distribution, with the majority demonstrating no obvious clinical symptoms. However, some cases with special locations can lead to clinical presentations related to mass or pressure effects on adjacent structures.

To date, a total of 67 cases of benign fat-forming SFT have been reported in the English literature. As shown in Table 1, fat-forming SFTs arise mainly in middle-aged patients (mean, 50.2 years; range 11–88 years), with only one paediatric patient aged 11 years reported so far. The patients comprised 40 males and 27 females, demonstrating a male-to-female ratio of 3:2, which is inconsistent with previous reports in the literature. Fat-forming SFTs display a wide anatomical distribution, with the most commonly affected sites being the lower extremities (18/67) including the thigh, hip, calf, popliteal fossa, perineum, inguina and male external genitalia. The second-most common site is the retroperitoneal area (12/67), with other sites including the thoracic cavity (8/67), head and neck (8/67), upper extremities (4/67), orbit (4/67) and pelvic cavity (3/67). The reported size of fat-forming SFTs ranges from 0.8 to 21.0 cm (mean, 7.4 cm). Among the 67 cases of benign fat-forming SFT, 47 patients were followed up, with none developing a recurrence or metastasis. However, the mean follow-up time was only 22.7 months, and long-term follow-up is required to draw definitive conclusions regarding the prognosis of fat-forming SFT.

Although SFTs are typically benign tumors, they can show malignant histological features and malignant behaviors. In a large series of 223 intrathoracic cases, histological features suggestive of malignant SFT included increased cellularity, pleomorphism, mitotic count

Sixteen cases of malignant fat-forming SFT have been reported, with their clinical information listed in Table 2. These cases showed an age range of 20–93 years (mean, 61.3 years), gender distribution of 9 males and 7 females, and size range of 3.4–20.0 cm (mean, 9.2 cm). As with benign fat-forming SFTs, the most commonly affected sites were the lower extremities (7/16). Although most cases of reported malignant fat-forming SFTs (10/16) have a favorable prognosis, this tumor type still has the potential to be fatal. Two female patients have died of due to multi-organ metastasis to the lung, spine, breast, bone and soft tissue. Therefore, several risk stratification models have been designed to achieve more precise prognostic prediction by combining histological and clinical parameters. The most widely used model to predict metastatic risk was established by Demicco et al. [50] and incorporates patient age, tumor size, mitotic count and tumor necrosis . Using this model, SFTs can be classified into low risk (score 0–3), intermediate risk (score 4–5) and high risk (score 6–7) groups. The case presented here was aged 65-years (scored as 1) with a tumor diameter of 12 cm (scored as 2) and a mitotic count of 1/10 HPF (scored as 1), thus falling into the intermediate risk group. A three-tiered, integrated risk stratification model incorporating mitotic count, density of Ki-67+ and cluster designation 163 (CD163)+ cells, and mechanistic target of rapamycin (MTOR) mutation was recently proposed to more accurately predict whether SFT patients are at high risk of tumor progression [51]. In our case, the mitotic index of 1/10 HPF and Ki-67 expression of 10% in tumor cells were both low according to the above criteria.

Surgery remains the treatment of choice of fat-forming SFTs since it allows definitive diagnosis and treatment. In addition to surgery, some patients with malignant fat-forming SFT receive adjuvant radiotherapy and chemotherapy [41]. Radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy and anti-angiogenic therapy are promising options that have shown varying efficacy in the treatment of SFT following surgery [52, 53, 54]. However, robust evidence is still lacking for the routine use of preoperative or postoperative adjuvant therapy in the treatment of SFT, including fat-forming SFT. Although doxorubicin has been the first-line therapy in advanced soft-tissue sarcoma for over 40 years, it has been suggested that doxorubicin-based chemotherapy should be avoided for SFT because its low efficacy means that it could be detrimental overall [52]. Anti-angiogenic therapy such as pazopanib, and immunotherapy with programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitors and PD-1 ligand (PD-L1) inhibitors, may be a treatment option for typical SFTs [55]. A preclinical study focused on RNA targeting technology to specifically suppress the expression of NAB2-STAT6 fusion transcripts, thereby providing a promising foundation for novel, targeted treatment of SFT [56]. However, the various adjuvant therapies require further validation through randomized trials, as well as biological studies to better understand and predict the mechanisms of efficacy and resistance [54].

The diagnosis of SFT can be quite challenging due to its rarity, requiring an integrated approach that includes specific clinical, histological, IHC and even molecular findings. Combining the location of the mass with imaging findings, an ovarian sex cord-stromal tumor (thecoma) was initially considered by our radiologists. When MRI images are reviewed retrospectively, as in the present case, the fatty and hypervascular components of fat-forming SFT become very apparent, since the T1-weighted images make the fat appear bright (Fig. 1A). This may lead to a broader differential diagnosis that includes rarer lipomatous lesions such as angiomyolipoma and liposarcoma. Currently, a diagnosis of fat-forming SFT can be made by combining histological characteristics with IHC staining results. Histologically, most fat-forming SFTs resemble the cellular form of SFT, except for the presence of mature, non-atypical adipocytes. A combination of CD34, CD99 and BCL-2 IHC staining has traditionally been used to diagnose fat-forming SFT. However, although these IHC markers are sensitive, they are not sufficiently specific to distinguish fat-forming SFT from other pathological entities. STAT6 has emerged as a highly sensitive and specific IHC marker, with most SFTs demonstrating diffuse and strong nuclear expression [57]. Further studies and recently published case reports have confirmed the utility of STAT6 IHC staining in the diagnosis of fat-forming SFTs [58]. Moreover, the detection of NAB2-STAT6 fusion genes can help with the diagnosis of fat-forming SFT, since these are a hallmark of SFTs [37]. In the present case, tumor cells in the specimen were diffusely stained for STAT6. However, a limitation of our case report is that we did not perform NAB2-STAT6 fusion gene detection. In addition to STAT6, a recent study using next-generation sequencing revealed that several other genes, including peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-

The main histological differential diagnosis of fat-forming SFT includes angiomyolipoma, liposarcoma, spindle cell lipoma, gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST), and schwannoma with fatty degeneration. Angiomyolipoma is typically composed of variable amounts of thick-walled vessels, as well as smooth muscle components that are immunoreactive for SMA, HMB45 and Melan-A, but negative for CD34. Well-differentiated liposarcoma typically displays infiltrative growth, unlike the well-encapsulated fat-forming SFT, and IHC and FISH analysis also show positive staining for MDM2 in the tumor cells. Spindle cell lipoma usually occurs in the subcutaneous tissue of the neck and upper back of male patients and does not contain hemangiopericytomatous vasculature. GISTs contain characteristic bundles of spindle cells that are immunoreactive for cluster designation 117 (CD117), CD34, and discovered on GIST 1 (DOG-1). Moreover, GISTs do not contain mature adipocytes. Schwannoma is usually strongly immunoreactive for S-100 protein, but negative for CD34. In summary, histological evaluation along with appropriate supplementary methods are important steps in the accurate diagnosis and treatment of fat-forming SFT.

This study reviewed the current English literature on fat-forming SFTs, and described the clinical and molecular features of a gynecological, retroperitoneal fat-forming SFT case. Although the fat-forming SFT cases reported to date were not specifically related to gynecology, this rare tumor variant should still be included in the differential diagnosis when hypervascular components are observed in addition to fatty components in the field of gynecology. Classical radiological features of fat-forming SFTs are prominent hypervascular and fatty components. Surgical resection remains the gold standard treatment for this rare tumor type. The application of radiotherapy, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, anti-angiogenic therapy, or molecular-targeted therapy requires further validation before clinical application. Careful histopathological evaluation and appropriate supplementary methods such as IHC staining and gene testing techniques are pivotal for correct diagnosis. A multidisciplinary medical team is required for the treatment and long-term management of fat-forming SFTs. Further studies based on more fat-forming SFT cases are required to obtain a deeper understanding of this rare tumor.

The datasets used or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

MH and KC collected the data and wrote the manuscript; ZW, QW and JZ analyzed the data a and literature review; FR collected and analyzed the data. MH, KC and FR saw and verified all the raw data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and ethical approval was approved retrospectively from the Ethics Committee of Women’s Hospital, Zhejiang University School of Medicine (approval no. IRB-20230194-R). The patient provided written informed consent for this study for the publication of this study.

Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This study was funded by the the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82101799).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/CEOG40729.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.