1 Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, National Taiwan University Hospital, 115006 Taipei, Taiwan

2 School of Medicine, College of Medicine, Fu Jen Catholic University, 242062 New Taipei, Taiwan

3 Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Fu Jen Catholic University Hospital, 242352 New Taipei, Taiwan

4 Department of Health and Welfare, University of Taipei, 100234 Taipei, Taiwan

5 Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Taipei City Hospital, Zhongxiao Branch, 241008 Taipei, Taiwan

6 Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Taipei City Hospital, Heping Branch, 100065 Taipei, Taiwan

7 Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Taipei City Hospital, Fuyou Branch, 100027 Taipei, Taiwan

Abstract

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the most common gynecological malignancy, and its incidence has recently increased. Several screening tools have been developed, including the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, cervical methylation test, traditional transvaginal ultrasound (TVU), three-dimensional TVU (3D-TVU), circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA), and direct endometrial sampling. Each screening methods differ in characteristics, cost, and accuracy.

A systematic review was conducted to assess publications offering different perspectives on screening methods for EC and to identitify viable methods in practice, using PubMed and Google Scholar for studies published between 1995 and 2024. In addition, different strategies were summarized, and their cost-effectiveness was evaluated.

Known detection methods include various screening tools. Herein, we provide a comparison of current early diagnostic and screening tools for EC and their accuracy, and review existing knowledge on screening methods while identifying viable methods for clinical practice. Currently, no optimal screening method exists for EC.

With the increasing global incidence of EC, the demand for effective EC screening is more noteworthy. Concerning cost-effectiveness, convenience, and complications, it has been suggested that TVU or DNA methylation testing in cervical samples may be preferable options. Additionally, differential diagnosis of other etiologies and patient education regarding red-flag signs are also important.

Keywords

- endometrial cancer

- screening

- Pap smear

- DNA methylation

- transvaginal ultrasound

- accuracy

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the sixth most common cancer in women, with 420,368 newly diagnosed cases worldwide in 2022, and the highest disease burden in North America and Western Europe [1, 2]. The prevalence was higher in Caucasian areas, such as North America and Western Europe, while it was relatively low in Asia, Africa, and South America. Several risk factors are associated with EC. From the perspective of geographic, socioeconomic, and racial disparities, EC is more prevalent in high-income and developed countries than in low-income, middle-income, and developing countries, and access to high-quality healthcare and oncologist density may be attributed to this phenomenon [2, 3, 4]. African-American women are diagnosed with poorer prognostic histological subtypes and higher stages and grades of EC than European women [5]. Additionally, obesity was another risk factor, particularly for endometrioid EC, with approximate relative risks of 1.5 fold for those with overweight, 2.5 fold for those with class 1 obesity [body mass index (BMI), 30.0–34.9 kg/m2], 4.5 for those with class 2 obesity (BMI, 35.0–39.9 kg/m2) and 7.1 fold for class 3 obesity (those with BMI

Most clinical presentation was post-menopausal bleeding, which could be easily noted for patients [2]. In a systematic review and meta-analysis [3], the pooled prevalence of post-menopausal bleeding among women with EC was approximately 90%, irrespective of tumor stage, whereas overall percentage of EC in post-menopausal bleeding was approximately 9%; that is, 10% ECs may have delayed diagnosis and management. Thus, the development of screening tests and guidelines of EC is crucial for early detection and treatment, which further improves the survival rate and prognosis in EC. Currently, some screening methods, such as the Papanicolaou (Pap) smear, cervical methylation test, two-dimensional (2D) or three-dimensional (3D) transvaginal ultrasound (TVU), circulating tumor cells, and direct endometrial biopsy, have been postulated. However, no detailed comparison and introduction of screening tests have been conducted. Therefore, in this study, we enumerated and compared different screening methods for EC.

A systematic review aimed at assessing and comparing the methods for screening EC was performed.

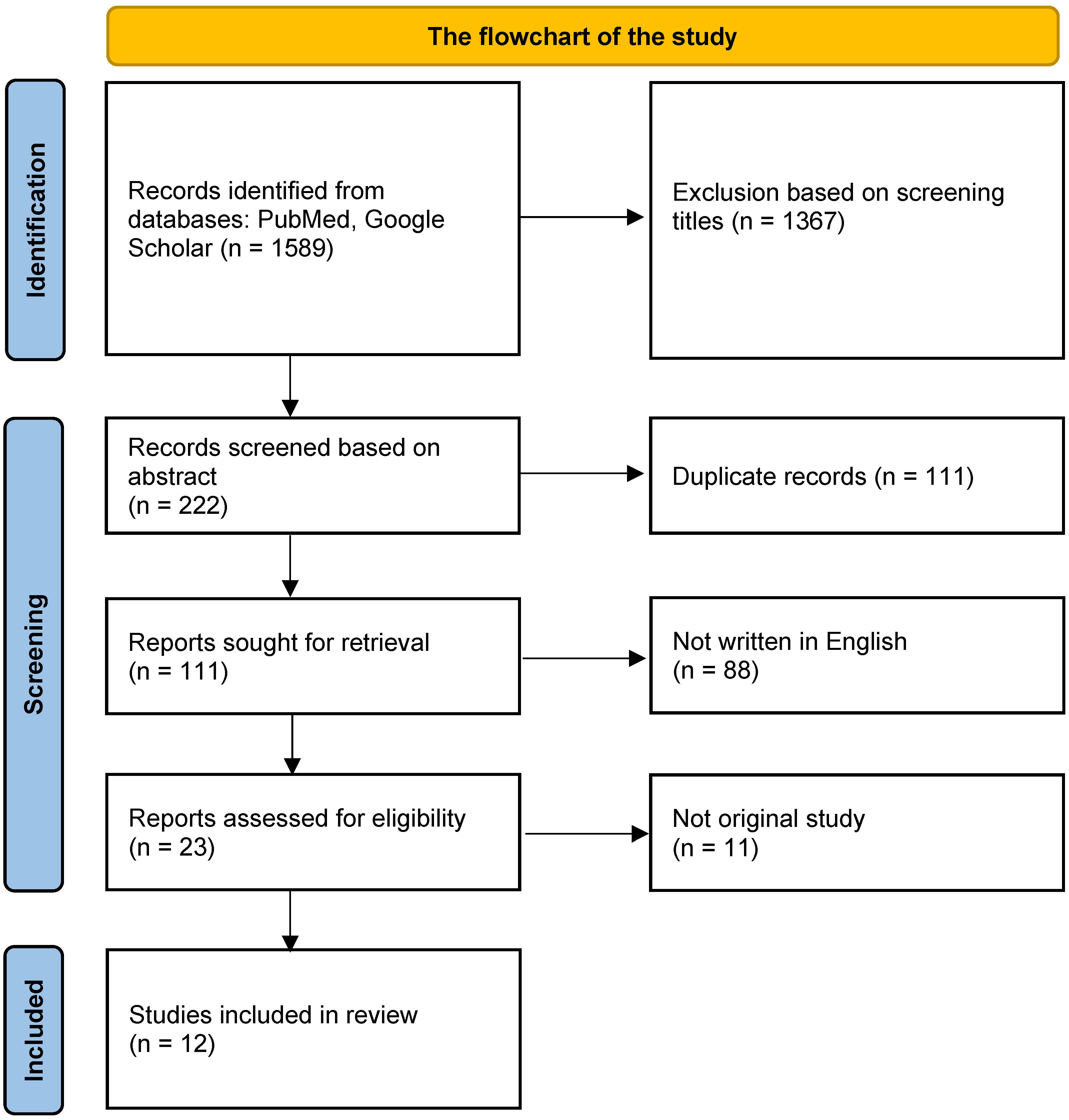

This systematic review was undertaken and reported in adherence to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) [11] (Fig. 1). All relevant articles were searched for in the following databases: PubMed and Google Scholar with the keywords “endometrial cancer screening”, “Pap smear”, “DNA methylation”, “transvaginal ultrasound”, “3D ultrasound”, “circulating tumor cells”, and “endometrial biopsy” (Supplementary Table 1). All scientific publications between 1995–2024. The articles were limited to those written in English language. In this systemic review, all the inclusive characteristics were evaluated carefully, such as author and year, study type, location, study subjects, intervention measures, study results, etc. (Supplementary Table 2). In addition, the quality of each study was evaluated. The principle of Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) [12] was used to evaluate the quality of the study to assess the quality of non-randomized studies and a modifed version of NOS for cross-sectional studies [13].

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The flowchart of the study.

Currently, there is no optimal screening method for EC [2, 14]. The known detection methods include various screening tools. Table 1 lists a comparison of current early diagnosis and screening tools for EC and their accuracy, including the Pap cervical smear, traditional 2D ultrasound, 3D ultrasound, DNA methylation in cervical sampling, and endometrial sampling by surgical procedures.

| Screening method | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|

| Papanicolaou (Pap) smear | 45% | Not assessed (NA) |

| DNA methylation in cervical sampling | 83.7–96.0% | 69–99% |

| Transvaginal ultrasound (TVU) -for post-menopausal female (cut-off 5 mm) | 33–90% | 48–85.7% |

| Three-dimensional (3D) ultrasound with power Doppler (without post-menopausal bleeding) | For endometrial volume: 74.2% | For endometrial volume: 60.6% |

| For vascular index: 90.3% | For vascular index: 81.8% | |

| Endometrial sampling | 75–95% | 92–100% |

| Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) | 10–22% | 95% |

Table 2 compares the characteristics, advantages, and disadvantages of different methods. The details are discussed and compared below.

| Screening method | Characteristics | Advantages | Disadvantage |

| Pap smear | With test stick to obtain a cervical specimen at transitional zone | - Also for cervical cancer screening | - Possible discomfort during exam |

| - Low invasiveness and cost | - No direct sampling of the endometrium in cavity | ||

| DNA methylation in cervical sampling | Abnormalities in methylation increase cancerous risk | - High accessibility | - Corresponding genetic indicators needed according to different races |

| - At the same time with Pap smear | |||

| - Expensiveness in comparison to Pap smear | |||

| TVU | First-line screening tool | - Non-invasive method | - EM thickening not necessarily cancerous |

| Detection EM blood flow, other EM lesions, and adnexa lesions | - Low discomfort sensation | ||

| - Low specificity | |||

| - Operator dependence | |||

| - No consensus of definition on EM thickening pre-menopause | |||

| 3D ultrasound with power Doppler (without PMB) | Identification three dimensions at the same time | More clear and precise image than traditional TVU | - Expensiveness |

| - Not yet popularized | |||

| Two current mainstream modes: recombining 2D images, or obtaining images directly through a specialized 3D probe | - Artifacts may present, causing misreading | ||

| Endometrial sampling (brush, lavage, suction) | Sampling EM tissue with brush, lavage, suction, including Tao brush, EndPap, Endocyte | Direct acquirement of EM tissue | - Discomfort sensation |

| Bleeding after examination | |||

| - Local sampling, possibly missing lesions | |||

| CtDNA | Gain the genetic information of tumor cells in blood (recently, new methods with urine or vaginal tampon) | - Noninvasiveness | - Risk for not acquirement of tumor DNA fragments |

| - Convenience | |||

| - Expensiveness |

Abbreviations: EM, endometrium; PMB, post-menopausal bleeding; 2D, two-dimensional.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis [14], the overall pooled sensitivity was 45% (95% confidence interval [CI], 40–50%). This percentage was significantly higher among those with non-endometrioid histology than that in those endometrioid subtypes (77% [95% CI, 66–87%] vs. 44% [95% CI, 34–53%], respectively). Additionally, some clinical factors influenced the results, with higher sensitivity in advanced stages, more myometrial invasion, positive abdominal cytology, lymph node metastasis, cervical involvement, and lympho-vascular invasion.

Additional genetic detection in Pap smears could increase sensitivity. In a study analyzing two methylomic databases of endometrioid-type EC [15], 14 genes that were hypermethylated in EC were found with best performance with basic-helix-loop-helix E22 (BHLHE22), cysteine dioxygenase 1 (CDO1), and CUGBP Elav-like family member 4 (CELF4) (sensitivity of 83.7–96.0% and specificity of 78.7–96.0%). Additionally, a study [16] testing methylation status by quantitative methylation-specific polymerase chain reaction for 14 genes in DNA pools of endometrial and ovarian cancer tissues demonstrated that POU class 4 homeobox 3 (POU4F3) and Membrane associated guanylate kinase, WW and PDZ domain containing 2 (MAGI2) are valid with sensitivity of 83–90% and specificity 69–75% for detection of EC. In a retrospective study [17] using PapSEEK (assays for mutations in 18 genes as well as an assay for aneuploidy), 81% of the Pap brush samples from women with EC were positive, including 78% of patients with early-stage disease and 92% of those with late-stage disease. Only 1.4% of the Pap brush samples from 714 women without cancer were PapSEEK-positive, meaning specificity of approximately 99%.

In a case-control study of post-menopausal study [18], sensitivity and specificity at endometrial thickness 5 mm or greater cut-off were 80.5% and 85.7% for EC and atypical endometrial hyperplasia. For a cut-off of 10 mm or greater, sensitivity and specificity were 54.1% (45.3–62.8) and 97.2% (97.0–97.4). The optimal cut-off for endometrial thickness was 5.15 mm, with sensitivity of 80.5% and specificity of 86.2%. A comparison between TVU and endometrial aspiration was conducted among asymptomatic post-menopausal women potentially eligible for an osteoporosis prevention trial [19]. In this population, the estimated sensitivities for TVU with threshold values of 6 and 5 mm were 17% and 33%, respectively. In a study published in The New England Journal of Medicine [20], at a threshold value of 5 mm for endometrial thickness, TVU had a positive predictive value (PPV) of 9% for detecting any abnormality, with 90% sensitivity, 48% specificity, and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 99% for post-menopausal conditions.

In patients with breast cancer with tamoxifen, the sensitivity was 63.3% and specificity was 60.4% by setting the endometrial thickness cut-off at more than 9 mm to represent significant abnormality. Additionally, PPVs were 43.3% and NPV was 77.5% [21].

In a study conducted in Southern India [22], the sensitivity and specificity of endometrial volume were 74.2% and 60.6% with a cut-off of 4.52 mL. However, the optimal parameters for EC were vascularization index (sensitivity, 90.3%; specificity 78.8%; cut-off, 2.02) and vascularization flow index (sensitivity, 90.3%; specificity, 81.8%; cut-off, 0.76). In a systematic review [23], endometrial volume estimation was more specific than endometrial thickness measurement for predicting EC in post-menopausal bleeding (specificity, 12–88% vs. 36–99%). However, regarding the sensitivity of volume estimation and endometrial vascular assessment using 3D-power-Doppler, the results are controversial.

Currently, there are several methods for obtaining endometrial tissue, such as the classic dilatation and curettage (D&C), hysteroscopy, Pipelle sampling, and Tao Brush.

D&C, considered the ‘gold standard’ method for acquiring endometrial tissue and diagnosis, allows for the examination of 50–60% of the lining surface, while the percentage of non-diagnostic results reaches 3% [24, 25]. With the use of Pipelle endometrial sampling [26], sensitivity and specificity were 75% and 100% for EC, respectively. However, sensitivity decreased to 12.5% for endometrial polyp. In a systematic review and meta-analysis [27], cytological examination using Tao brush for endometrial premalignancy and malignancy revealed pooled sensitivity of 95%, specificity of 92%, and diagnostic odds ratio of 184.84. Furthermore, in a genetic analysis with Tao brush [17], 93% samples patients with EC contained genetic alterations detected by PapSEEK, most common with phosphatase and tensin homolog (PTEN) (63%), tumor protein p53 (TP53) (42%), phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA) (36%) mutations.

At the 2018 American Society of Clinical Oncology annual meeting, GRAIL Biotechnology reported that the sensitivity of ctDNA detection for uterine cancer was

Generally, ultrasound examination is the first line choice for the evaluation of endometrial abnormalities in patients with symptoms, such as abnormal uterine bleeding, owing to its ability to evaluate endometrial thickness or morphology, and even blood flow of the endometrium. The generally accepted threshold (cut-off value) for post-menopausal women is 4–5 mm (sensitivity 98%; specificity 36–68%). In fact, sensitivity and specificity are significantly affected by the threshold. If the cut-off value increases, the specificity also significantly increases, thereby reducing unnecessary invasive examinations [30]. However, not all patients with EC exhibit significant endometrial thickening. Especially in patients with type II EC, the endometrium is relatively unaffected by estrogen stimulation, and sometimes it is difficult to identify and has a worse prognosis; therefore, raising the threshold will risk delaying the diagnosis. Furthermore, there is currently no consensus on the decision value for premenopausal women or for those using hormonal medications (such as tamoxifen).

Recently, 3D TVU has been developed to visualize the coronal plane, which is difficult to visualize using traditional ultrasound. The bilateral uterine horns, endometrium, and cervix can be identified from a single plane, providing clearer and more precise images than traditional TVU. The function of 3D ultrasound also includes the use of power Doppler imaging to measure vascular blood flow. Excessive blood flow may originate from angiogenic tumors, thereby helping physicians to determine whether there are abnormalities within the uterus.

3D ultrasound, compared with the diagnostic accuracy of 2D ultrasound, is similar [31]. Moreover, studies have shown that the specificity and sensitivity of 3D ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are almost the same [32]. Although the time spent is less than that of MRI examination, 3D ultrasound has a high potential to become a good tool in screening and diagnosis.

The newly developed testing method, the cervical methylation test, can analyze methylated genes using cervical smear specimens to identify those who are truly at high risk, and then conduct invasive examinations to confirm the diagnosis, eliminating the need for additional procedures. However, validation is still needed because the technique is new and the price of screening is very high.

The development of ctDNA is currently not a good biomarker of EC. Ongoing studies have focused on tumor molecules in the blood, including ctDNA, circulating tumor cells, circulating microRNA (miRNA), etc. CtDNA has benefits in post-treatment tracking and early identification of cancer recurrence. For early diagnosis, a study has also used methylated DNA to successfully distinguish affected from unaffected individuals [33]. However, it is sometimes difficult to detect mutations in all tumor genes in blood samples. Furthermore, precision tests are expensive, and some patients may not be able to afford them. Limited laboratories perform genetic testing, and they have not yet been widely used clinically. The sensitivity ranges from

Finally, a direct endometrial biopsy is the gold standard for diagnosing EC. Diagnostic rates can be achieved at different levels, depending on how the specimen is obtained. In the early days, the Tao Brush and Pipelle tubes were the mainstream methods of aspiration. In recent years, endometrial D&C and hysteroscope-assisted slicing has been commonly used. Compared with the first two methods, hysteroscopy is the only method to observe the endometrial pattern with the naked eye, by which suspicious lesions can more accurately obtained, such as abnormal vessels, surface smoothness, papillary structures, and polypoid structures [34], thereby increasing the diagnostic rate and reducing false negatives. However, sampling is associated with surgical risks. In addition to postoperative pain and bleeding, it may cause uterine rupture, fluid overload, and anesthesia-related complications. A Study indicates that approximately 6% of patients suffer from cervical stenosis or intraoperative pain, which prevents the performing physician from completing the examination [35].

The incidence and prevalence of EC have increased in the past few years; thus, the demand for screening has come to the forefront [36]. According to a statistical study [37], the PPV and NPV are influenced by prevalence. As the prevalence increased, the PPV also increased, but the NPV decreased. Therefore, with an increasing number of cases, screening for EC is becoming more important. From a public health perspective, costs and benefits must be considered. We take the current situation in Taiwan as an example. The range of costs for Pap smear, DNA methylation in cervical sampling, TVU, 3D ultrasound with power Doppler, ctDNA, D&C, hysteroscopic examination, and even polypectomy varies widely (8 to 2667 US dollars) (Table 3). An optimal screening test must be inexpensive, accessible, and highly sensitive. Pap smear is the most inexpensive method, but it has very low sensitivity. For TVU, the cost is only 32 US dollars and the sensitivity can approach approximately 90%, ranging between 33–90%. The price of 3D ultrasound with power Doppler is 24 times higher than the price of TVU; however, studies revealed that its sensitivity is only approximately 74.2–90%. Methylation of DNA in cervical sampling is less expensive than 3D ultrasound with higher sensitivity than that of 3D ultrasound (83.7–96.0% vs. 74.2–90%). Endometrial sampling is relatively inexpensive and sensitive, with a cost of only 39 US dollars. However, bleeding and discomfort during the examination must be considered. D&C and hysteroscopic methods are the most precise; however, the demand for anesthesia, risk of bleeding, and perforation make them inconvenient; thus, they are not good screening methods. D&C and hysteroscopic procedures are important for diagnosis. CtDNA is the most expensive and has poor sensitivity; therefore, further investigation is required. Thus, it is postulated that in view of cost-effectiveness, public health, convenience, and complications, TVU and DNA methylation in cervical sampling are the most feasible methods for screening, and can be performed for those at risk, such as those with obesity, positive family history, poorly controlled metabolic syndrome, and previous history of polycystic ovary syndrome with the use of tamoxifen. Furthermore, patient education for red flag signs (abnormal bleeding, recent weight loss, abdominal or pelvic discomfort, lower urinary tract symptoms, and gastrointestinal symptoms) and differential diagnosis of other etiologies of bleeding are also important in clinical practice. Therefore, further studies and guidelines are recommended in the future.

| Screening method | Cost (US dollars) |

| Pap smear | 8 |

| DNA methylation in cervical sampling | 500 |

| TVU | 32 |

| 3D ultrasound with power Doppler (without post-menopausal bleeding) | 100 |

| Endometrial sampling | 39 |

| Dilatation and curettage (not including anesthesia) | 60 |

| Hysteroscopic exam (not including anesthesia) | 68 |

| Hysteroscopic polypectomy (not including anesthesia) | 336 |

| CtDNA | 2667 |

Abbreviation: US, United States; D&C, dilatation and curettage.

1. The articles were reviewed without using any statistical tools or methods.

2. We searchd articles in Pubmed and Google Scholar. However, not all studies worldwide were included.

3. We analyzed the cost-effectiveness only in Taiwanese situation rather globally and without any statistical evidence.

4. The range of sensitivity and specificity among different methods are wide, making it difficult to calculate the definite cost-effectiveness of screening tests.

5. This study is a literature systemic review rather than a meta-analysis, and thus heterogeneity analysis and integration or pooling among different studies were not performed.

With the increasing number of EC worldwide, the demand for EC screening is more noteworthy. Concerning cost-effectiveness, convenience, and complications , we postulated that TVU or DNA methylation in cervical sampling may be better options. Additionally, the differential diagnosis of other etiologies and patient education regarding red flag signs are also important.

The data sets generated and analyzed during the current study are available in the web repository: PubMed and Google Scholar.

CCL, ACS and CCC designed the research study and performed the research. CHC, SCL and CLL made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance and instruction from Department of education and Research, Taipei City Hospital.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/CEOG33417.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.