1 Reproductive Medicine Center, The Second Hospital of Lanzhou University, 730030 Lanzhou, Gansu, China

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The First Affiliated Hospital, and College of Clinical Medicine of Henan University of Science and Technology, 471003 Luoyang, Henan, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Vitamin D deficiency (VDD) and insulin resistance (IR) are well-known risk factors for recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL). Since VDD may contribute to the development of IR, this study aimed to investigate the role of fasting insulin (FINS) levels and the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR) in the association between vitamin D and RPL.

A total of 934 women were retrospectively analyzed between 2019 and 2022, including patients with RPL and age-matched controls. Clinical and biochemical data were collected, including serum 25(OH)D, FINS, fasting blood glucose (FBG), HOMA-IR, and sex hormone levels. Correlation, multivariate logistic regression, restricted cubic spline (RCS), and mediation analyses were conducted.

Compared to controls, the RPL group exhibited lower levels of 25(OH)D and higher levels of FINS and HOMA-IR. In the RPL group, 25(OH)D was negatively correlated with FINS and HOMA-IR. Higher levels of 25(OH)D were associated with reduced RPL, whereas elevated FINS and HOMA-IR levels were linked to an increased risk. A mediation analysis confirmed that FINS and HOMA-IR partially mediated the relationship between vitamin D and RPL, accounting for 10.9% and 10.7% of the total effects, respectively.

VDD is closely associated with increased RPL risk, potentially through impaired glucose metabolism. Therefore, improving vitamin D status and insulin sensitivity may help in reducing pregnancy loss and enhancing reproductive outcomes.

Keywords

- vitamin D

- recurrent pregnancy loss

- fasting insulin

- insulin resistance

- mediating effect

Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin that plays an essential role in maintaining the calcium and phosphorus balance, promoting bone health. In recent years, it has been recognized for its essential biological functions in immune regulation, inflammation inhibition, cell proliferation, and differentiation [1, 2, 3]. Recurrent pregnancy loss (RPL) is a common pregnancy complication that has generated significant concern [4]. Although the exact etiology remains unclear, more and more evidence shows that vitamin D deficiency (VDD) may be closely related to the occurrence and development of RPL [5, 6, 7]. Previous studies have found that with the increase of vitamin D level, the clinical pregnancy rate (CPR) also increases, while the miscarriage rate (MR) decreases [6, 8]. These findings support the crucial role of vitamin D in pregnancy, especially in avoiding RPL.

Glucose metabolism plays a vital role during pregnancy, providing necessary energy and nutrition for the normal development of embryos [9, 10]. Some studies have found a complex interaction between vitamin D and glucose metabolism [11, 12, 13, 14]. Vitamin D receptor (VDR) is widely expressed in islet cells, suggesting that vitamin D may affect glucose metabolism through insulin secretion and resistance [15, 16]. Therefore, exploring the relationship between VDD and RPL, as well as its potential mechanistic involvement in glucose metabolism, is essential for understanding the etiology of RPL and finding preventative and therapeutic strategies.

This study explores the potential role of vitamin D in the occurrence and development of RPL and whether there is a mechanism related to glucose metabolism disorder. The result of the study will help provide a theoretical basis for clinical intervention research and individualized treatment in the future.

This retrospective study analyzed 934 patients who visited the Reproductive Medicine Center of the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University between September 2019 to February 2022. This study was approved by the hospital’s ethics committee. Inclusion criteria were as follows: ① Age between 18 and 40 years; ② Natural conception and no use of assisted reproductive technologies; ③ For the RPL group: history of two or more consecutive spontaneous or induced abortions before 14 weeks of gestation, consistent with the clinical diagnostic criteria for RPL; ④ For the control group: age-matched women without a diagnosis of RPL. Women with no history of pregnancy loss or with one or two isolated (non-recurrent) early miscarriages were eligible for inclusion in the control group, provided they had at least one successful pregnancy. Exclusion criteria included: ① Use of assisted reproductive technology (e.g., in vitro fertilization, intracytoplasmic sperm injection); ② Known chromosomal abnormalities; ③ Chronic metabolic or endocrine diseases (e.g., diabetes, thyroid dysfunction, cardiovascular diseases); ④ Use of medications known to affect glucose or lipid metabolism; ⑤ Vitamin D supplementation within 3 months before or during pregnancy; ⑥ More than four previous pregnancies; ⑦ Severe pregnancy complications such as gestational hypertension, early fetal demise or placental insufficiency.

The included population was divided into two groups according to their history

of pregnancy: the RPL group and the normal control group. Then, according to the

serum 25(OH)D level, the patients in the RPL group were divided into the VDD

group [defined as 25(OH)D

Maternal baseline data were obtained from the hospital’s electronic medical record system. Collected variables included sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., maternal age, education), reproductive history (e.g., gravidity, parity, pregnancy loss), lifestyle factors (e.g., smoking, alcohol consumption, manual labor), and clinical measurements (e.g., blood pressure, lipid profile). Pregnancy outcomes were obtained through a review of hospital records and telephone follow-ups.

The primary outcomes of this study were the occurrence of RPL, serum 25(OH)D level, fasting insulin (FINS) level, and the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), to investigate the effect of vitamin D on RPL and the potential mediating role of FINS and HOMA-IR. Secondary outcomes included CPR (defined as the presence of an intrauterine gestational sac and yolk sac), clinical live birth rate (LBR) (defined as the delivery of a live fetus after 28 weeks of gestation), MR (defined as pregnancy losses before 20 gestational weeks, including spontaneous abortion and termination due to intrauterine fetal death) and sex hormone levels [18, 19, 20].

Serum biochemical parameters were measured using standardized protocols and were

measured during the early follicular phase (days 2–5 of the menstrual cycle)

during routine preconception or reproductive evaluations. All participants were

in a non-pregnant state at the time of blood collection. The measured parameters

include 25(OH)D, FINS, estradiol (E2), luteinizing hormone (LH), and

follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) were measured using an

electrochemiluminescence immunoassay on the cobas® 8000 analyzer

(Roche Diagnostics, e801, Mannheim, Germany), in accordance with the

manufacturer’s instructions. Lipid profiles, including total cholesterol (TC),

triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and low-density

lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C), were determined by enzymatic colorimetric

methods using the cobas® 8000 analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, c702,

Mannheim, Germany). Fasting blood glucose (FBG) was measured using the glucose

oxidase-peroxidase method on the cobas® 8000 fully automated

biochemical analyzer (Roche Diagnostics, c702, Mannheim, Germany). HOMA-IR was

calculated as [FINS (mIU/L)

Statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk,

NY, USA) and R version 4.2.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna,

Austria). Graphs were created using the ggplot2 (https://ggplot2.tidyverse.org) and plotRCS (https://cran.r-project.org/src/contrib/Archive/plotRCS/) packages. Missing

data were handled using multiple imputations with chained equations, assuming

data were missing at random. A two-sided p-value

Table 1 summarizes the baseline characteristics of women in the RPL group and the control group. Compared with the control group, women in the RPL group had a significantly higher cumulative number of pregnancies (3.00 vs. 1.00) and prior pregnancy losses (2.00 vs. 1.00), but fewer previous live births (0.00 vs. 1.00). The RPL group also exhibited lower serum 25(OH)D levels (31.16 nmol/L vs. 35.05 nmol/L) and a higher proportion of VDD (46.10% vs. 34.90%). Additionally, FINS levels (9.77 mIU/L vs. 7.97 mIU/L) and HOMA-IR (2.17 vs. 1.73) were elevated in the RPL group. No significant differences were observed in maternal age, height, weight, body mass index (BMI), education level, manual labor proportion, smoking proportion, drinking proportion, age at menarche or first pregnancy, FBG, or lipid parameters.

| RPL group (n = 516) | Control group (n = 418) | p | |

| Maternal age (years) | 30.00 (28.00, 33.00) | 30.00 (28.00, 32.00) | 0.32 |

| Height (cm) | 161.00 (159.00, 165.00) | 161.00 (158.00, 165.00) | 0.95 |

| Weight (kg) | 57.00 (52.00, 53.00) | 55.85 (51.00, 63.00) | 0.25 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.88 (20.20, 23.88) | 21.48 (19.53, 20.03) | 0.32 |

| Advanced education (%) | 58.10 (300/516) | 64.10 (268/418) | 0.06 |

| Engaged in manual labor (%) | 11.00 (57/516) | 13.20 (55/418) | 0.32 |

| Smoking (%) | 0.60 (3/516) | 0.50 (2/418) | 0.83 |

| Drinking (%) | 1.90 (10/516) | 2.20 (9/418) | 0.82 |

| Menarche age (years) | 13.00 (13.00, 14.00) | 13.00 (13.00, 14.00) | 0.67 |

| First pregnancy (years) | 26.00 (24.00, 29.00) | 27.00 (24.00, 28.00) | 0.92 |

| Cumulative numbers of pregnancy | 3.00 (2.00, 3.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 2.00) | |

| Numbers of previous live birth | 0.00 (0.00, 0.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 2, 00) | |

| Numbers of prior pregnancy loss | 2.00 (2.00, 3.00) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | |

| 25(OH)D (nmol/L) | 31.16 (22.51, 41.56) | 35.05 (25.57, 45.20) | |

| VDD (%) | 46.10 (238/516) | 34.90 (146/418) | |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 4.93 (4.66, 5.29) | 4.94 (4.67, 5.20) | 0.46 |

| FINS (mIU/L) | 9.77 (6.97, 12.94) | 7.97 (5.67, 12.10) | |

| HOMA-IR | 2.17 (1.49, 2.88) | 1.73 (1.25, 2.61) | |

| TC (mmol/L) | 3.78 (3.35, 4.27) | 3.80 (3.29, 4.39) | 0.65 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.91 (1.68, 1.32) | 0.94 (1.73, 1.34) | 0.20 |

| HDL-C (mmol/L) | 1.33 (1.14, 1.53) | 1.29 (1.11, 1.55) | 0.36 |

| LDL-C (mmol/L) | 2.39 (2.03, 2.82) | 2.41 (2.02, 2.88) | 0.65 |

Note: All continuous variables were non-normally distributed and are therefore presented as median (P25, P75). Group comparisons were conducted using non-parametric tests.

RPL, recurrent pregnancy loss; BMI, body mass index; VDD, vitamin D deficiency; FBG, fasting blood glucose; FINS, fasting insulin; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol.

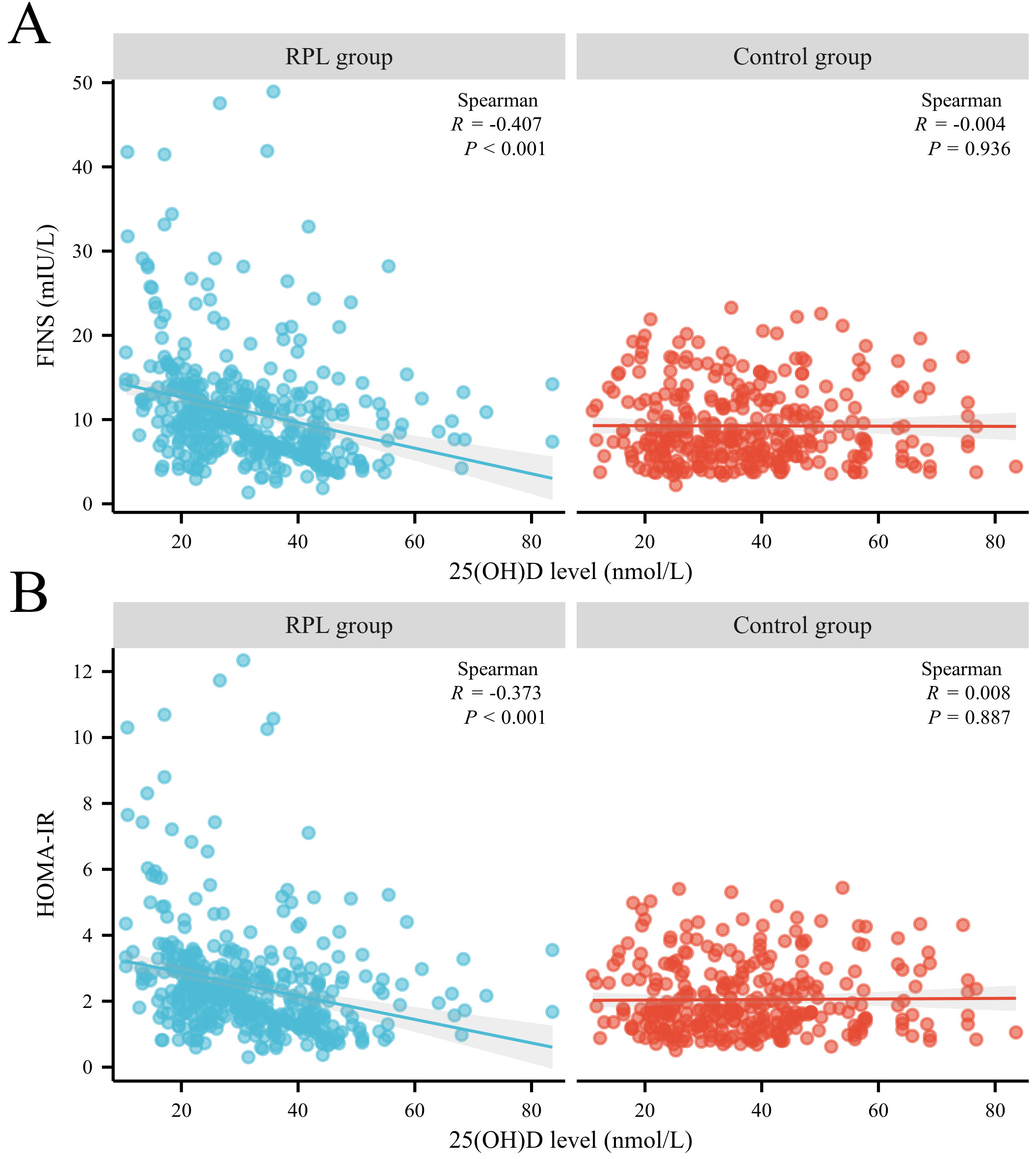

Fig. 1 shows the correlations between 25(OH)D and FINS or HOMA-IR. In the RPL

group, Spearman analysis revealed significant negative correlations between

25(OH)D and FINS (r = –0.407, p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The correlation between serum 25(OH)D level, FINS level, and HOMA-IR between patients with RPL and the control group. (A) Correlation between 25(OH)D and FINS in both groups. (B) Correlation between 25(OH)D and HOMA-IR in both groups. HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; FINS, fasting insulin; RPL, recurrent pregnancy loss.

After adjusting for potential confounding factors, multivariate logistic

regression analysis (Table 2) demonstrated that higher serum 25(OH)D levels were

significantly associated with a decreased risk of RPL [adjusted odds ratio (aOR):

0.98, 95% CI: 0.97–0.99, p

| OR | aOR | 95% CI | p | ||

| 25(OH)D | 0.98 | 0.98 | 0.97–0.99 | ||

| FINS | 1.06 | 1.06 | 1.03–1.09 | ||

| HOMA-IR | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.23–1.44 | ||

| Vitamin D status | |||||

| Sufficiency | Ref | Ref | Ref | ||

| Insufficiency | 1.17 | 1.20 | 0.80–1.80 | 0.38 | |

| Deficiency | 1.80 | 1.77 | 1.18–2.68 | ||

Note: Adjusted for confounding factors including maternal age, BMI, reproductive history, lifestyle factors, blood pressure, and lipid profiles.

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

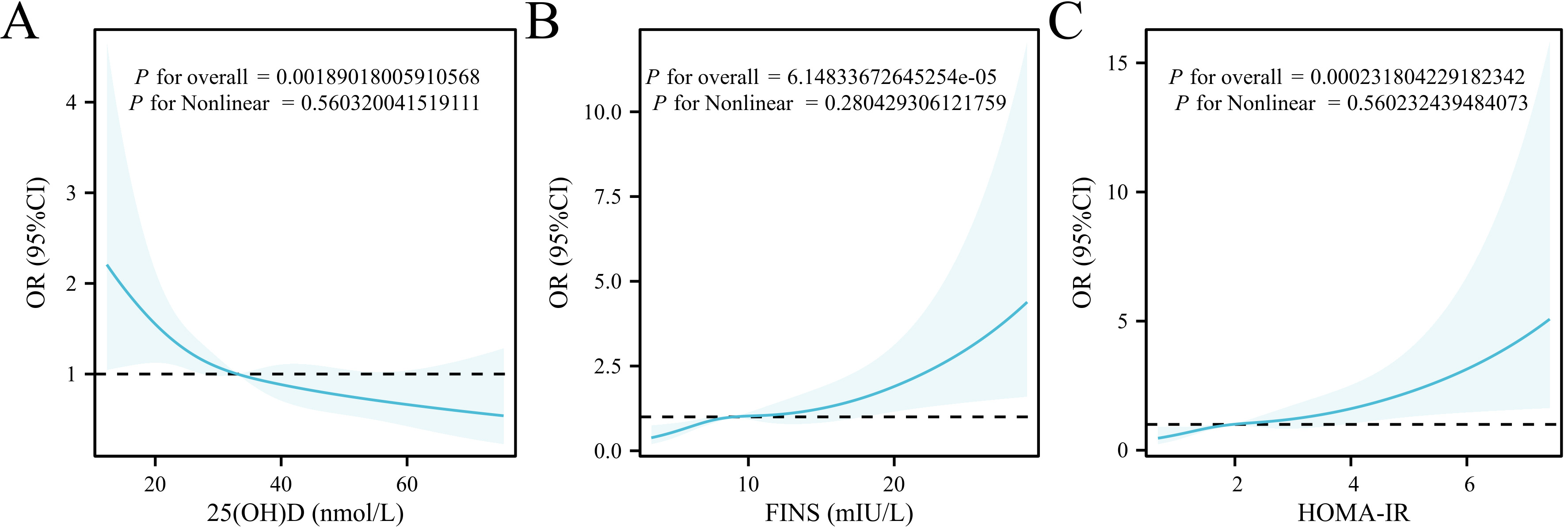

To further investigate the potential dose-response relationship and assess the

linearity of these associations, we performed RCS analyses within logistic

regression models adjusted for the same confounders. The results showed

significant overall associations for 25(OH)D (p = 0.0019), FINS

(p = 0.00006), and HOMA-IR (p = 0.0002) with RPL. However, none

of the nonlinear components were statistically significant (all p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

RCS analysis of the associations between 25(OH)D, FINS, HOMA-IR, and RPL. (A) RCS curve between 25(OH)D and RPL. (B) RCS curve between FINS and RPL. (C) RCS curve between HOMA-IR and RPL. RCS, restricted cubic spline; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

Mediation analysis revealed that both FINS and HOMA-IR partially mediated the association between 25(OH)D and RPL (Table 3). The indirect effects were statistically significant: FINS (OR = 0.9962, 95% CI: 0.9929–0.9986) and HOMA-IR (OR = 0.9963, 95% CI: 0.9929–0.9986), explaining 10.9% and 10.7% of the total effect, respectively.

| Effect value | OR | 95% CI | Proportion mediated | ||

| FINS | |||||

| Direct effect | –0.0310 | 0.9695 | 0.9584–0.9807 | - | |

| Indirect effect | –0.0038 | 0.9962 | 0.9929–0.9986 | 10.9% | |

| HOMA-IR | |||||

| Direct effect | –0.0308 | 0.9697 | 0.9585–0.9807 | - | |

| Indirect effect | –0.0037 | 0.9963 | 0.9929–0.9986 | 10.7% | |

Note: Adjusted for confounding factors including maternal age, BMI, reproductive history, lifestyle factors, blood pressure, and lipid profiles. An indirect effect was considered statistically significant if the 95% CI did not include zero.

Patients in the RPL group were further stratified into VDD, insufficiency, and

sufficiency subgroups. Compared to patients with sufficient vitamin D, those with

deficiency had significantly elevated FINS and HOMA-IR levels (p

| RPL group | p | |||

| vitamin D deficiency (n = 238) | vitamin D insufficiency (n = 219) | vitamin D sufficiency (n = 59) | ||

| LH (IU/L) | 5.70 (4.20, 7.50) | 5.00 (3.80, 6.50) | 4.20 (3.40, 6.30) | |

| FSH (IU/L) | 7.70 (6.20, 8.60) | 6.40 (5.90, 7.50) | 6.10 (5.20, 7.80) | |

| E2 (pmol/L) | 41.00 (29.80, 57.30) | 42.00 (31.50, 52.70) | 46.50 (36.70, 67.40) | 0.29 |

| FBG (mmol/L) | 4.90 (4.70, 5.30) | 4.90 (4.70, 5.20) | 5.10 (4.60, 5.40) | 0.75 |

| FINS (mIU/L) | 11.40 (9.10, 14.00) | 7.60 (5.90, 11.20) | 8.60 (5.10, 12.00) | |

| HOMA-IR | 2.50 (2.00, 3.10) | 1.70 (1.30, 2.50) | 1.90 (1.10, 2.70) | |

| CPR (%) | 58.80 (140/238) | 63.50 (139/219) | 72.90 (43/59) | 0.12 |

| LBR (%) | 54.20 (13/24) | 63.30 (19/30) | 69.20 (9/13) | 0.61 |

| MR (%) | 29.20 (7/24) | 20.00 (6/30) | 15.40 (2/13) | 0.61 |

Note: p-values were adjusted using the Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons among the three vitamin D subgroups. For LBR and MR, the total number of cases analyzed was less than the group size because, at the time of data collection, only a portion of patients had complete pregnancy outcomes; others were either still pregnant or awaiting conception.

LH, luteinizing hormone; FSH, folliclestimulating hormone; E2, estradiol; CPR, clinical pregnancy rate; LBR, clinical live birth rate; MR, miscarriage rate.

RPL is a common adverse outcome in pregnancy with a multifactorial etiology. Although the exact mechanisms remain unclear, increasing evidence suggests that VDD may play a crucial role in the onset and progression of RPL [22]. In this study, we observed lower serum 25(OH)D levels and a higher prevalence of VDD among women with RPL compared to control subjects. Concurrently, FINS levels and HOMA-IR were elevated in the RPL group and negatively correlated with serum 25(OH)D concentrations, suggesting a potential link between vitamin D status and glucose metabolism in the pathogenesis of RPL.

Previous studies have reported a high prevalence of VDD among women with RPL [23]. A meta-analysis demonstrated that VDD is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage, with women receiving vitamin D supplementation having significantly lower odds of miscarriage (OR: 1.94, 95% CI: 1.25–3.02) [8]. In our study, patients in the RPL group exhibited lower serum 25(OH)D levels compared to controls (31.16 nmol/L vs. 35.05 nmol/L), along with a higher prevalence of VDD (46.10% vs. 34.90%). These findings align with previous research and highlight the potential role of vitamin D in maintaining pregnancy health. Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that increasing serum 25(OH)D levels were significantly associated with a decreased risk of RPL (aOR: 0.98, 95% CI: 0.97–0.99), suggesting that VDD may act as a risk factor for RPL.

However, the underlying mechanisms linking low vitamin D levels to increased

miscarriage risk remain unclear. One widely accepted hypothesis is that vitamin D

exerts immunomodulatory effects that are critical for successful pregnancy.

Ota et al. [24] reported that 1,25(OH)2D3 significantly inhibits the

cytotoxicity of natural killer (NK) cells, downregulates pro-inflammatory

cytokines such as interferon-

In addition to peripheral immune modulation, vitamin D is also thought to influence the maternal-fetal interface. A study has found significantly reduced levels of 25(OH)D, transforming growth factor-beta, and VDR in the decidual tissue of RPL patients, alongside elevated levels of IL-17 and IL-23 [25]. Given that 25(OH)D negatively regulates the IL-23/IL-17 axis, these findings suggest that insufficient vitamin D may impair local immune tolerance at the maternal-fetal interface, further increasing the risk of pregnancy loss [26].

Furthermore, glucose metabolism disturbances may represent another pathway linking VDD and RPL. Previous research has identified elevated insulin levels and HOMA-IR in women with RPL, both in natural conception and in those who used assisted reproduction [27, 28, 29]. In our cohort, RPL patients had higher FINS and HOMA-IR, and their increase was associated with greater RPL risk. Previous literature suggests that insulin resistance may impair endometrial vascularization, embryo development, and implantation, or lead to hypercoagulability and androgen excess, all of which may contribute to adverse pregnancy outcomes [30, 31, 32].

Importantly, our mediation analysis revealed that FINS and HOMA-IR partially mediated the association between 25(OH)D levels and RPL risk, accounting for 10.9% and 10.7% of the total effect, respectively. These findings suggest that glucose metabolism may serve as a mechanistic bridge between VDD and RPL. One potential mechanism is that VDD leads to reduced expression of insulin receptors on insulin-responsive cells, thereby decreasing insulin sensitivity and resulting in elevated circulating insulin levels [33]. Elevated insulin, in turn, may reduce the expression of glycoproteins at the implantation site and increase homocysteine levels, both of which could impair endometrial receptivity [34]. These alterations may disrupt endometrial blood flow and vascular integrity, ultimately compromising successful embryo implantation. Although subgroup analysis indicated that patients with VDD had higher FINS levels and HOMA-IR, and slightly worse reproductive outcomes, these trends did not reach statistical significance, likely due to limited sample size. Larger studies are needed to validate these associations.

Generally speaking, the results of this study emphasize the relationship between low levels of vitamin D and RPL and its potential regulation mechanism of glucose metabolism. However, it should be pointed out that this study has some limitations, including the relatively small sample size and the cross-sectional characteristics of the research design. Although this study is cross-sectional in design, all serum 25(OH)D measurements were conducted before pregnancy, and pregnancy outcomes were collected retrospectively or through follow-up. This temporal sequence helps mitigate, although not eliminate, the concern of reverse causality. Nevertheless, prospective studies are still warranted to clarify the causal direction of the association between vitamin D status and RPL. Therefore, further large-scale research and clinical trials are necessary to deeply understand the role of vitamin D in RPL and provide more powerful theoretical support for future intervention and treatment strategies. To sum up, vitamin D may be a potential therapeutic target, which is expected to play an essential role in preventing and managing RPL.

In summary, our study supports the hypothesis that VDD is associated with an increased risk of RPL and may act, at least in part, through dysregulation of glucose metabolism. FINS and HOMA-IR partially mediated the association between 25(OH)D and RPL, suggesting a novel mechanistic link. While these findings are promising, they are observational and cross-sectional. Future large-scale, prospective, and mechanistic studies are needed to confirm causality and elucidate the precise role of vitamin D and insulin pathways in the pathogenesis of RPL. Vitamin D may serve as a potential target for preventive or therapeutic interventions aimed at improving reproductive outcomes in women at risk of RPL.

aOR, adjusted odds ratio; CPR, clinical pregnancy rate; CI, confidence interval; E2, estradiol; FBG, fasting blood glucose; FINS, fasting insulin; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; HOMA-IR, homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance; HDL-C, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol; IR, insulin resistance; LBR, clinical live birth rate; LDL-C, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol; LH, luteinizing hormone; MR, miscarriage rate; NK, natural killer; OR, odds ratio; RCS, restricted cubic spline; RPL, recurrent pregnancy loss; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; VDD, vitamin D deficiency; VDR, vitamin D receptor.

The corresponding author can provide data with a reasonable request.

KW and FW jointly designed the study. RW and CW jointly collected the data; RW performed data analysis and wrote the statistical results section; CW verified the data, generated the figures, and contributed to writing the results description. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University (No: 2023 A-532). The need for written informed consent was waived by the Ethics Committee of the Second Hospital of Lanzhou University due to the retrospective nature of the study.

We thank Ejear for their professional manuscript editing service. The Figs. 1,2 in this study were created using Xiantao Academic (https://www.xiantaozi.com).

The research was supported by the Medical Innovation and Development Project of Lanzhou University (Grant No. lzuyxcx-2022-137), The Science Foundation of Lanzhou University (Grant No. 054000229) and A Real-World Study on RPL in China (Grant No. YJS-BD-19).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.