1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Zhongda Hospital, School of Medicine, Southeast University, 210009 Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Taixing People’s Hospital, 225400 Taizhou, Jiangsu, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

The coiled-coil domain-containing protein 80 (CCDC80) has known roles in signal transduction and as a structural protein that stabilizes the extracellular matrix (ECM). CCDC80 is also linked to drug resistance in cancers; however, the specific role of CCDC80 in platinum resistance in ovarian cancer (OC) remains unclear. This study used a variety of gene analysis and complementary experimental approaches to examine the prognostic significance of CCDC80 and the potential of this protein as a therapeutic target in OC.

Differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) datasets (GSE15372, GSE51373, GSE114206) using the Limma package. The Kaplan-Meier analysis highlighted CCDC80 as a key gene. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis (WGCNA) identified a CCDC80-related module as being enriched in cell chemotaxis and ECM remodeling pathways. Quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction, Western blotting, and immunohistochemistry were used to confirm CCDC80 expression in platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (PROC) cell lines and clinical samples. Functional assays (cell count kit-8, colony formation, flow cytometry) were used to evaluate cisplatin sensitivity. Lastly, gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), correlation analysis, and Western blotting were applied to investigate the mechanisms through which CCDC80 affected the platinum resistance of OC cells.

The Limma package and Kaplan-Meier analysis identified CCDC80 in the GEO datasets, and the WGCNA linked this protein to cell chemotaxis and ECM remodeling. The CCDC80 mRNA and protein expression levels were shown to be significantly higher in PROC cell lines and ovarian cancer tissue samples. Functional assays indicated that CCDC80 expression increases cisplatin resistance, while the GSEA and correlation analysis suggested that the epithelial–mesenchymal transition (EMT) pathway is a downstream target of CCDC80. Platinum resistance in OC cells was reduced by suppressing CCDC80 expression and increased by stimulating EMT, confirming the role of the CCDC80-EMT axis in platinum resistance.

This study shows that CCDC80 expression is significantly elevated in platinum-resistant OC cells and that platinum resistance arises from CCDC-mediated activation of the EMT pathway. The CCDC80-EMT link provides a new understanding of the mechanisms leading to platinum resistance in OC and highlights CCDC80 as a possible therapeutic target to prevent the development of chemotherapy resistance.

Keywords

- CCDC80

- platinum-resistant

- ovarian cancer

- epithelial-mesenchymal transition

Ovarian cancer (OC) remains one of the most lethal gynecological malignancies worldwide. Approximately 90% of OC are epithelial ovarian carcinomas (EOCs) comprising distinct histological subtypes with specific molecular alterations, clinical behaviors, and treatment responses (the remaining 10% are non-epithelial tumors including germ cell tumors, sex cord-stromal tumors, and rare variants such as small cell carcinomas) [1, 2, 3]. The high mortality primarily stems from late-stage diagnosis and the development of chemotherapy resistance [1, 2]. Platinum-based regimens are the mainstay treatment for EOCs, however, more than 70% of patients eventually develop resistance, leading to treatment failure [4, 5]. Despite extensive research, the molecular mechanisms underlying EOC platinum resistance remain incompletely understood, currently limiting our ability to identify effective therapeutic targets.

Recent studies have implicated the tumor microenvironment as mediating the development of chemotherapy resistance via multiple mechanisms, including extracellular matrix (ECM) remodeling and cell-cell interactions [1, 2]. Notably, the coiled-coil domain-containing protein 80 (CCDC80), a multifunctional protein involved in ECM stability and cell signaling [4, 5], has emerged as a potential regulator of tumor progression and drug resistance in various cancers [6, 7]. However, its specific role in OC platinum resistance remains unexplored, representing a significant knowledge gap in the field.

In this study, we investigated the function of CCDC80 in platinum-resistant OC (PROC) using integrated bioinformatics and experimental approaches. We first established the expression pattern and prognostic value of CCDC80 in ovarian cancer. Subsequent mechanistic studies revealed that CCDC80 promotes platinum resistance by regulating the epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT). These findings provide important new insights into OC drug resistance and identify CCDC80 as a potential therapeutic target to prevent OC developing platinum resistance during chemotherapy regimes.

Gene expression data from Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) (GSE15372) were processed for background correction, log2 transformation, and quantile normalization. Probes were mapped to gene symbols, and duplicates averaged. Using the Limma R package (v3.46.0, Bioconductor Core Team, Seattle, WA, USA), 907 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were identified (538 downregulated, 369 upregulated) with log2 fold change greater than 1.0 and an adjusted p-value less than 0.05. Cross-validation with datasets GSE51373 and GSE114206 confirmed consistent DEG expression trends.

Survival analysis was performed using the Kaplan-Meier Plotter online tool (https://kmplot.com/analysis/), which aggregates publicly available gene expression and clinical data from multiple ovarian cancer cohorts, including GSE14764, GSE15622, GSE18520, GSE19829, GSE23554, GSE26193, GSE26712, GSE27651, GSE30161, GSE3149, GSE51373, GSE63885, GSE65986, GSE9891, and The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) (total n = 1815 patients, Table 1).

| Characteristics | Categories | Cases (n) |

| Histological type | Serous | 1232 |

| Endometrioid | 62 | |

| Tumor stage | I | 107 |

| II | 72 | |

| III | 1079 | |

| IV | 189 | |

| Tumor grade | G1 | 56 |

| G2 | 325 | |

| G3 | 1024 | |

| G4 | 21 |

Note: Total sample size n = 1815. The sum of subgroups may not equal the total due to missing clinical information in some cases.

The WGCNA R package (v1.70, Bioconductor Core Team, Seattle, WA, USA) constructed a gene co-expression network with a soft threshold power of 10 for scale-free topology. Dynamic tree cut hierarchical clustering identified gene modules, and module-trait correlation analysis pinpointed key modules linked to platinum resistance (640 genes). The Gene Ontology (GO) framework, which includes categories such as biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF), was utilized to functionally annotate these module genes through an integrated enrichment analysis in conjunction with the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was conducted on The Cancer Genome Atlas-Ovarian Cancer (TCGA-OV) transcriptomic data to assess gene set enrichment from MSigDB (v2023.2, Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA). The clusterProfiler R package (v4.10.0, Bioconductor Core Team, Seattle, WA, USA) calculated the normalized enrichment score (NES), identifying significant pathways with a false discovery rate (FDR)

Paraffin tissue blocks from Zhongda Hospital, Southeast University, were sectioned to 3 µm. To retrieve antigens, samples were treated in a Tris-EDTA buffer (Solarbio, Cat#1033, Beijing, China) at pH 8 and 98 °C for 40 min, and endogenous peroxidase was neutralized with 3% hydrogen peroxide for 10 min. The tissue sections were incubated overnight at 4 °C with a rabbit anti-human CCDC80 antibody (Absin, Cat#abs127221, Shanghai, China; dilution 1:200). Subsequently, they were treated with an HRP-conjugated secondary antibody (Aifang Biotechnology, Cat#AFIHC004, Beijing, China; dilution 1:1) at room temperature for 50 min. Following this, the sections were counterstained with hematoxylin, fixed, dehydrated, and subjected to microscopic imaging post-color development.

All experiments were performed with randomization and blinding. Each experimental condition was independently repeated

The SKOV3 cell line was kindly provided by Dr. Hui Xu from the Department of Immunology, Southeast University School of Medicine. The SKOV3/DDP human cell line was purchased from Shanghai Jinyuan Biotechnology Co., Ltd. All cell lines were authenticated by STR profiling matching with ATCC databases and confirmed to be mycoplasma-free by PCR testing. Cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium (KeyGen Biotech, Cat#KGL1701-500, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China) with added supplements, including 10% fetal bovine serum (KeyGen Biotech, Cat#11011-9611, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China), 100 µg/mL penicillin, and 100 µg/mL streptomycin (Beyotime, Cat#C0222, Shanghai, China). CCDC80 knockdown (sh-CCDC80) and control (empty vector negative control, sh-NC) lentiviruses were produced by GenePharma (Shanghai, China). Transfections were performed following the manufacturer’s instructions, with medium replacement after 24 h. Stable transfectants were selected using 2 µg/mL puromycin (Biotech, Cat#ST551, Shanghai, China) for 2–3 generations.

RNA extraction from cell samples was conducted utilizing the TRIzol reagent (Vazyme Biotech, Cat#R401-01, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). Subsequent reverse transcription was performed employing the HiScript II Reverse Transcription Kit (Vazyme Biotech, Cat#R323-01, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China). qPCR was executed using SYBR Green dye (Vazyme Biotech, Cat#Q712-02, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China), with each sample analyzed in triplicate. Gene expression was quantified utilizing the 2-ΔΔCT method, employing glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) as the reference gene. The primer sequences were as follows:

CCDC80 (forward): 5′-GACCCCGTTTCACTATGCTGT-3′

CCDC80 (reverse): 5′-GGCGAGCTAGTCTCAACACG-3′

GAPDH (forward): 5′-ACAGTCAGCCGCATCTTCTT-3′

GAPDH (reverse): 5′-GACAAGCTTCCCGTTCTCAG-3′

RIPA buffer (Beyotime, Cat #P0013, Shanghai, China) along with protease inhibitors (Servicebio, G2008, Wuhan, Hubei, China) was used to lyse the cells. Protein samples were resolved via 4%–20% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) (ACE, Cat #F11420Gel, Changzhou, Jiangsu, China) and subsequently transferred onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes (Millipore, Cat#ISEQ00010, Burlington, MA, USA). The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk at ambient temperature and subsequently incubated overnight at 4 °C containing primary antibody specific for CCDC80 (Thermo Fisher, Cat #PA5-45821, Waltham, MA, USA; diluted 1:500), E-cadherin (Proteintech, Cat #20874-1-AP, Wuhan, Hubei, China; diluted 1:2000), VIM (Proteintech, Cat #60330-1-lg, Wuhan, Hubei, China; diluted 1:2000), or

Cell viability was evaluated utilizing the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) assay (Biosharp, Cat#K101837133EF5E, Hefei, Anhui, China). Cells in logarithmic growth phase were seeded into 96-well plates (WHB, Cat #WHB-96, Shanghai, China) at a density of 1

Cell apoptosis was assessed using the Annexin V–Fluorescein Isothiocyanate (V-FITC)/propidium iodide (PI) Apoptosis Detection Kit (Elabscience, Cat #E-CK-A211, Wuhan, Hubei, China) and quantified by flow cytometry. Single-cell suspensions were generated via trypsinization without ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (Beyotime, Cat#C0205, Shanghai, China)and subsequently washed with ice-cold PBS. The cells were incubated with recombinant human Annexin V-FITC for 5 min at room temperature in the dark, followed by a 30-minute incubation with PI at 4 °C in the dark. Apoptotic cells were identified using a BD FACSCelesta flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, Cat #657231, Becton Drive, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA), and the resulting data were analyzed with FlowJo software (v10.5.0, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA).

Exponential phase cells were exposed for 24 h to 5 µg/mL cisplatin (MACKLIN, Cat # D807330, Shanghai, China), then seeded into 6-well plates (WHB, Cat #WHB-6, Shanghai, China) at a density of 1000 cells per well. The cells were subsequently cultured at 37 °C in an atmosphere containing 5% CO2 until macrocolonies (consisting of more than 50 cells per colony) had formed. The colonies were then fixed for 30 min using 100% methanol (Biosharp, Cat #BL539A, Hefei, Anhui, China) and stained with a 0.1% crystal violet solution (Beyotime, Cat # C0121, Shanghai, China) for 30 min.

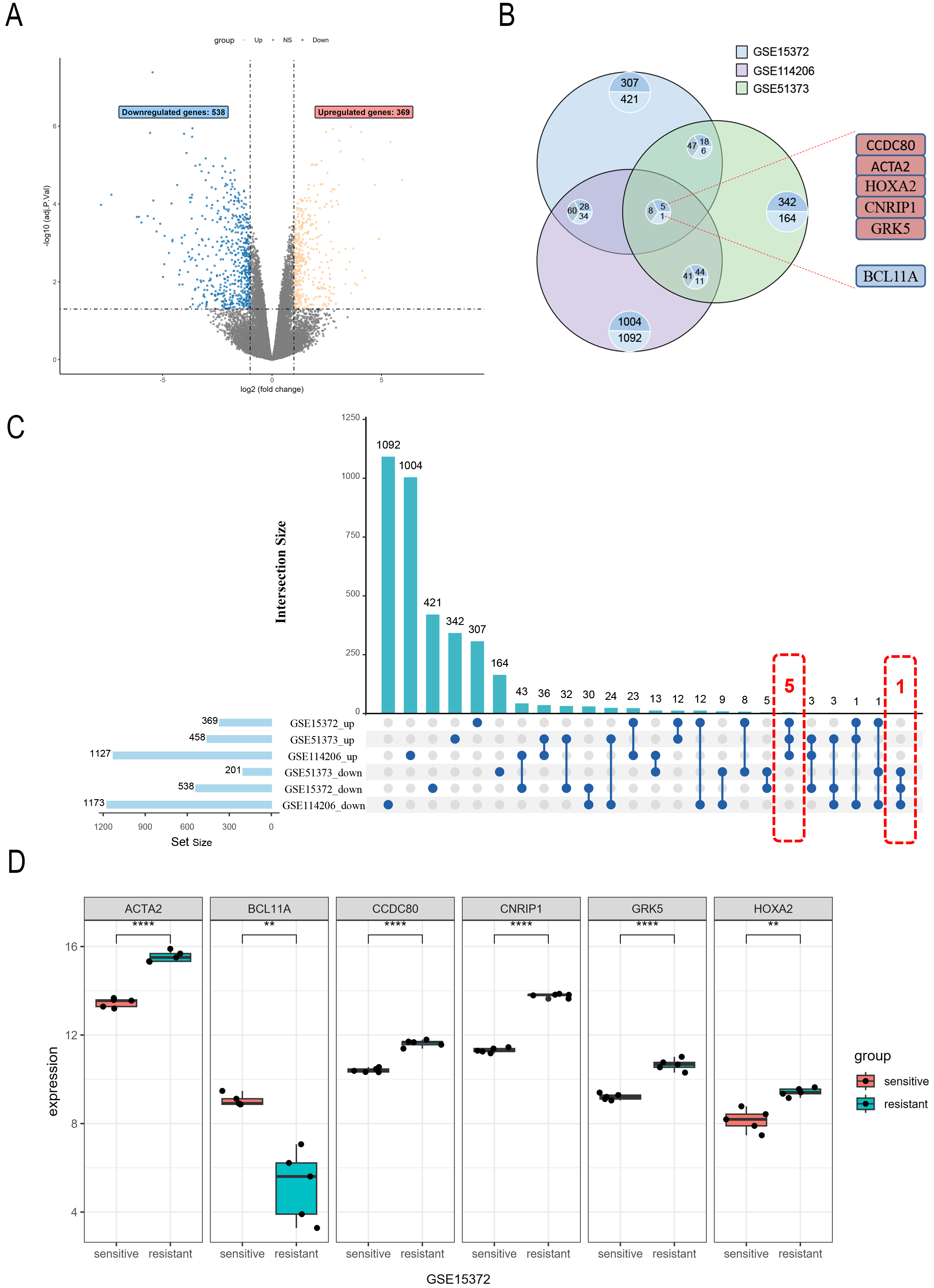

To explore the DEGs associated with PROC, we procured raw gene expression data from the GEO database (accession number: GSE15372). Following data preprocessing and normalization of the expression matrices across all datasets (Supplementary Fig. 1), we identified a total of 907 DEGs, comprised of 538 downregulated and 369 upregulated genes (Fig. 1A). Subsequent cross-validation using datasets GSE51373 and GSE114206 (Fig. 1B,C) revealed six co-expressed genes exhibiting consistent expression patterns (Supplementary Table 1). These include the upregulated genes CCDC80, ACTA2, HOXA2, CNRIP1, and GRK5, and the downregulated gene BCL11A (Fig. 1D).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Differential gene expression analysis in PROC datasets. (A) The GSE15372 dataset includes six cisplatin-resistant and six cisplatin-sensitive ovarian cancer cell samples; 369 upregulated genes and 538 downregulated genes are identified. Genes with non-significant changes in expression are shown in gray. (B) Intersection analysis of upregulated and downregulated genes from the GSE15372, GSE114206, and GSE51373 datasets. (C) The Upset plot illustrates the overlap of upregulated and downregulated genes across the three datasets, and the number of genes in each set. (D) Expression levels of differentially expressed genes (ACTA2, CCDC80, CNRIP1, GRK5, HOXA2, and BCL11A) in the GSE15372 dataset. ACTA2, CCDC80, CNRIP1, and GRK5 (**** p

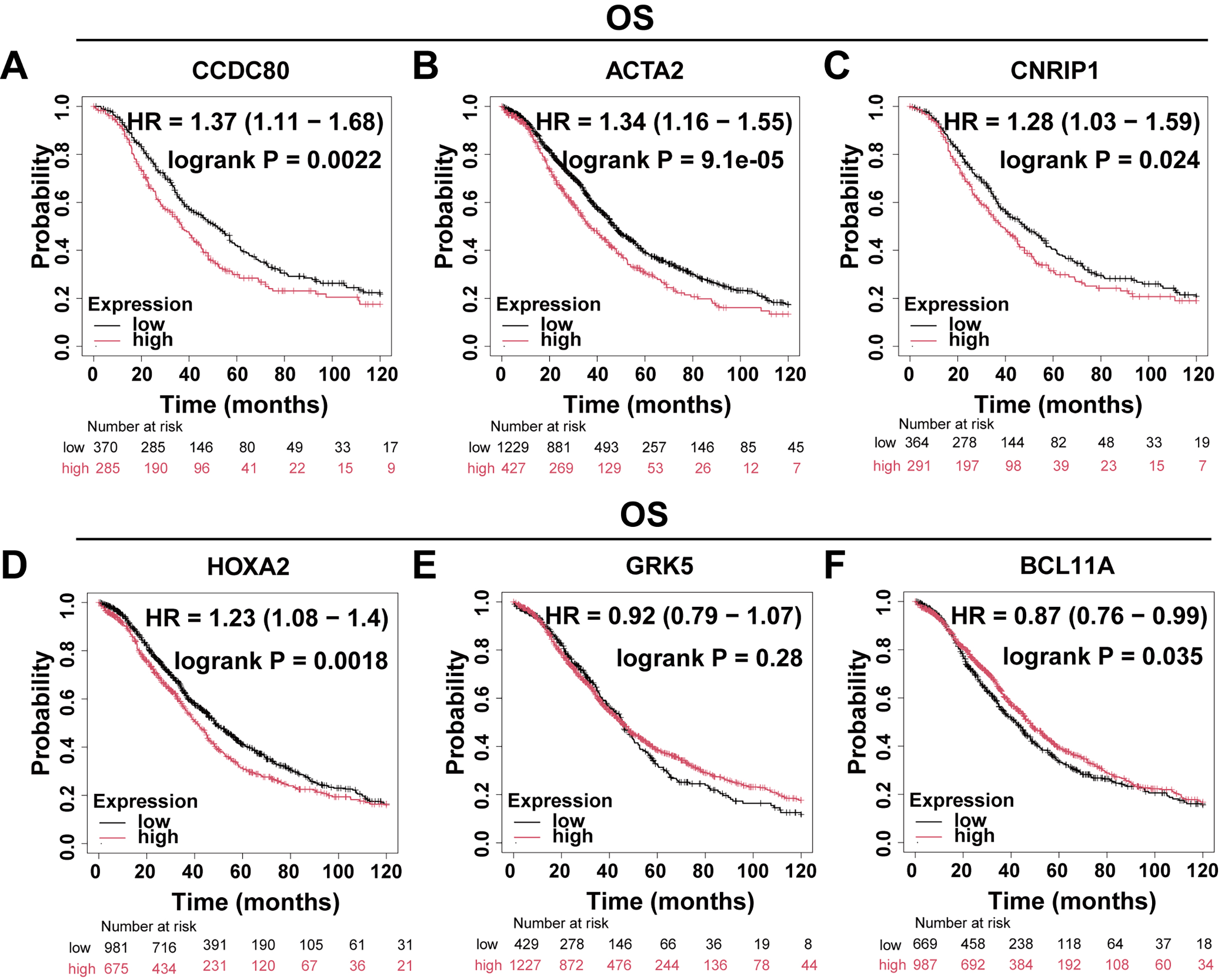

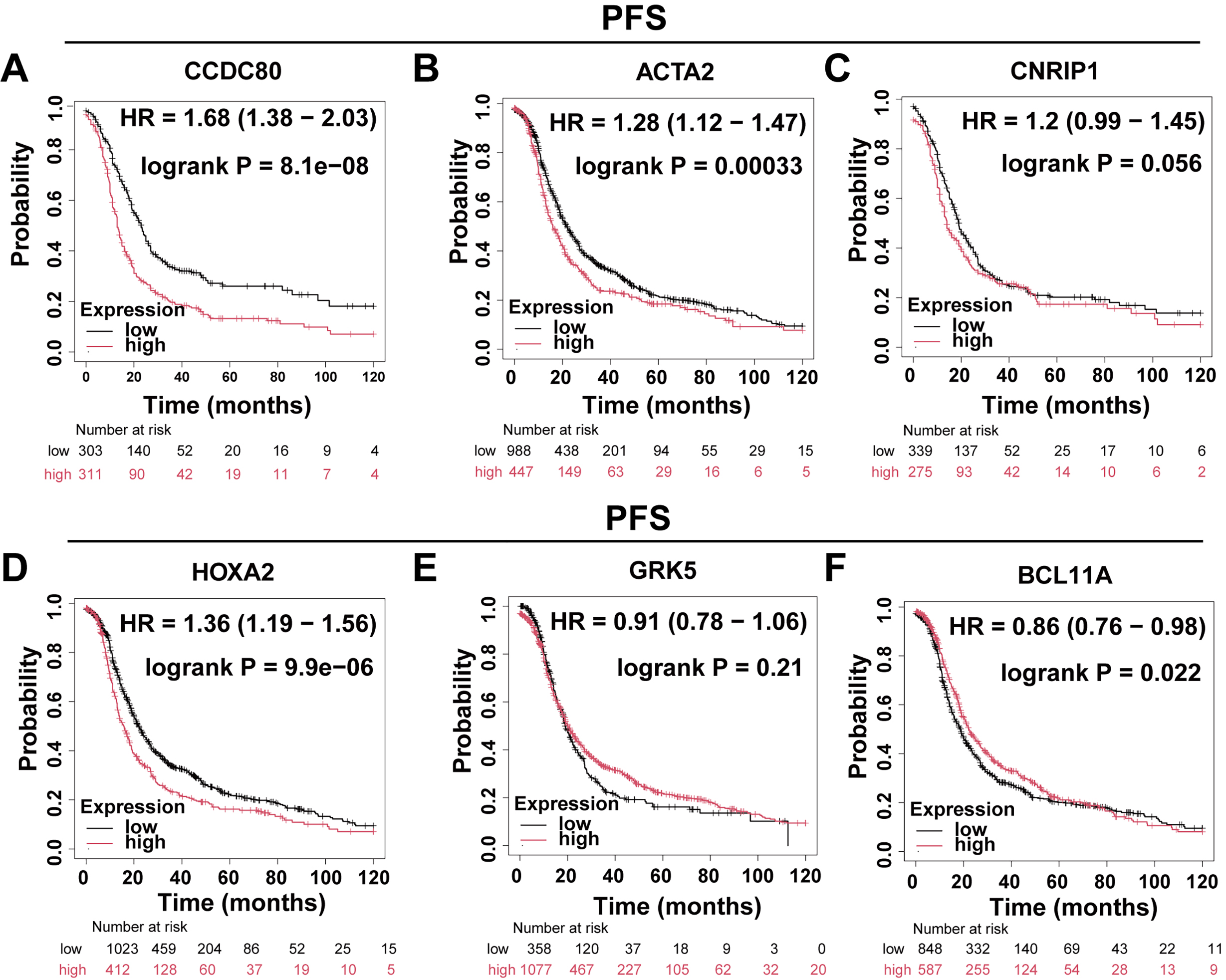

The Kaplan-Meier Plotter platform (https://kmplot.com/analysis/) was utilized to evaluate the Overall Survival (OS) and progression-free survival (PFS) of DEGs. The findings indicated that the expression levels of CCDC80, ACTA2, HOXA2, and BCL11A were significantly correlated with OS (Fig. 2A–F) and PFS (Fig. 3A–F) in patients with OC. Notably, CCDC80 demonstrated the highest hazard ratio (HR) for both OS and PFS, identifying it as the principal gene warranting further investigation.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Differential gene OS analysis. Patients with OC were divided into two groups based on gene expression levels, and Kaplan-Meier curves were used to compare the overall survival rates between these two groups. (A) CCDC80 (n = 655). (B) ACTA2 (n = 1656). (C) CNRIP1 (n = 655). (D) HOXA2 (n = 1656). (E) GRK5 (n = 1656). (F) BCL11A (n = 1656). OS, overall survival; HR, hazard ratio.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Differential gene PFS analysis. Patients with ovarian cancer were divided into two groups based on gene expression levels, and Kaplan-Meier curves were used to compare progression-free survival between these groups. (A) CCDC80 (n = 614). (B) ACTA2 (n = 1435). (C) CNRIP1 (n = 614). (D) HOXA2 (n = 1435). (E) GRK5 (n = 1435). (F) BCL11A (n = 1435). PFS, progression-free survival.

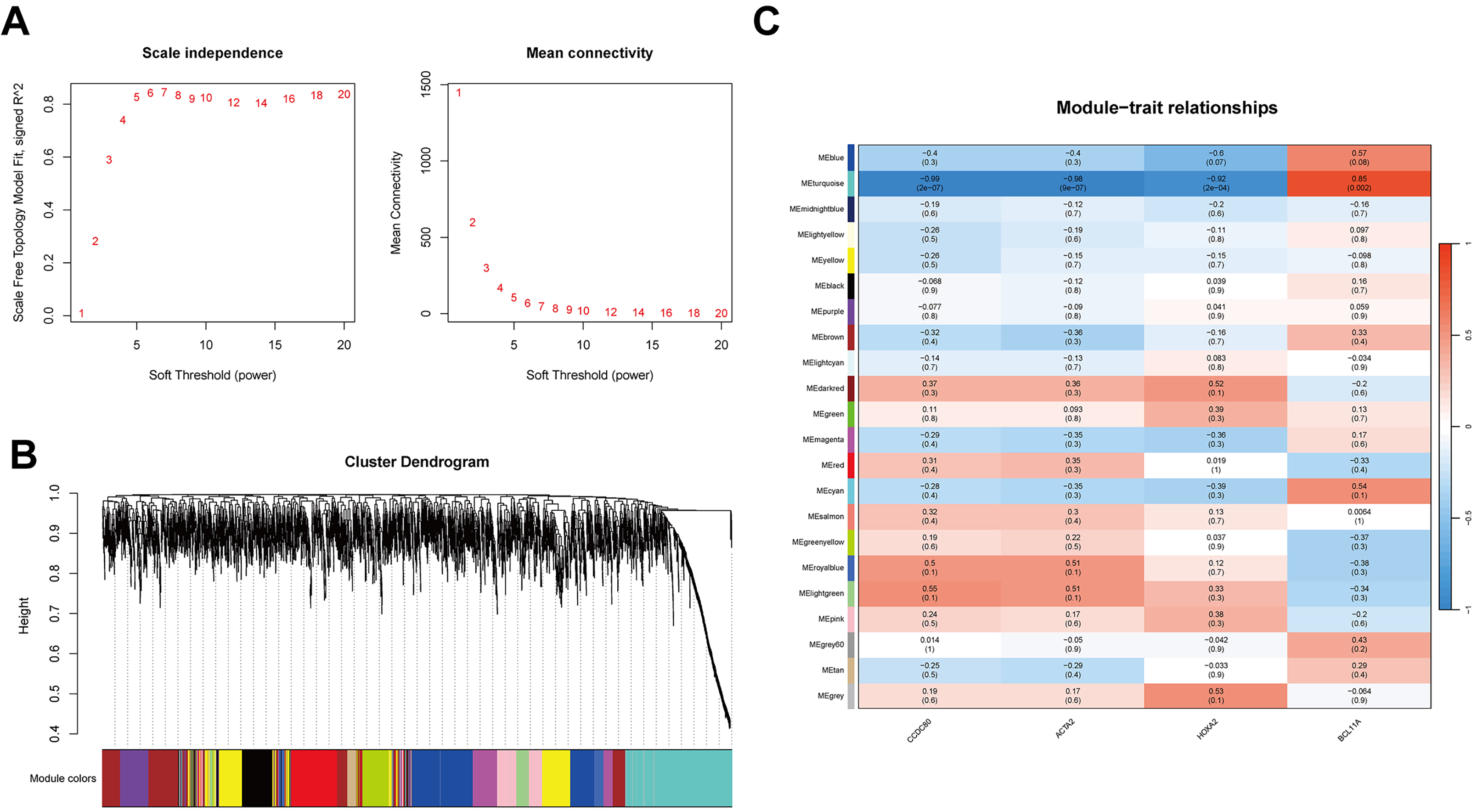

WGCNA was conducted to establish a co-expression network of DEGs. To maintain analytical precision, a soft threshold power of 10 was applied to delineate gene relationships within the dataset (Fig. 4A). Hierarchical clustering of the entire gene set unveiled several gene modules exhibiting significant co-expression patterns (Fig. 4B). Notably, the MEturquoise module demonstrated a robust correlation with platinum resistance and was consequently selected for further investigation due to its statistical significance (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. WGCNA and biological function analysis. (A) Selection of the soft threshold (power = 10) for WGCNA using scale independence and average connectivity. (B) Gene clustering dendrogram of the 21 modules identified by WGCNA. Branches of the dendrogram represent genes, with those showing similar expression clustered within the same module (color-coded). (C) Heatmap showing the correlation between WGCNA network modules and CCDC80, ACTA2, HOXA2, and BCL11A. WGCNA, weighted gene co-expression network analysis.

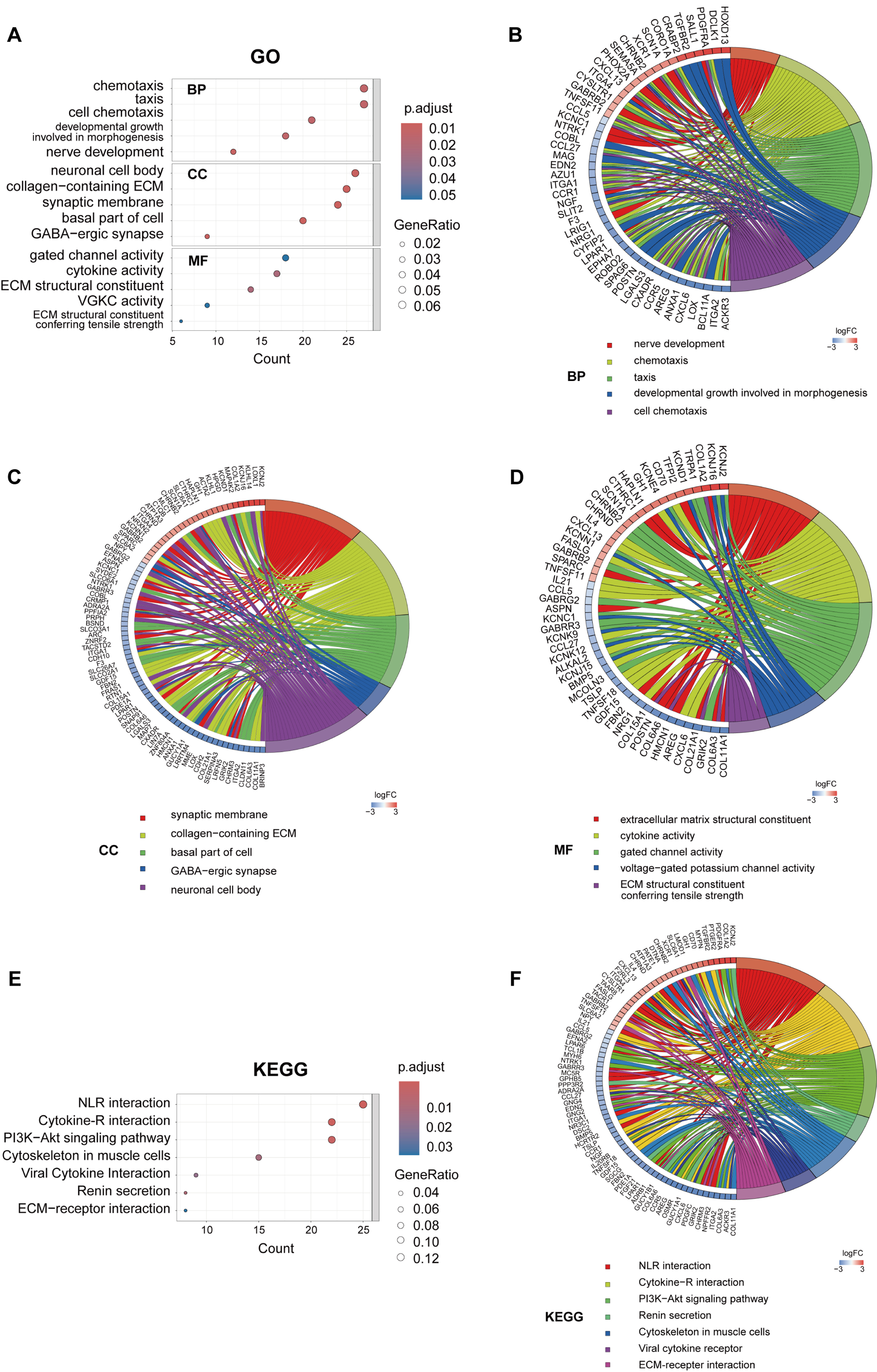

To elucidate the biological functions of key module genes, we conducted GO and KEGG enrichment analyses. The GO analysis revealed that these genes are predominantly involved in cell chemotaxis and ECM organization (Fig. 5A). Chord diagrams further demonstrated that the majority of genes within these pathways were downregulated, indicating a suppression of related pathways in PROC (Fig. 5B–D). The KEGG pathway analysis indicated that, alongside the suppression of cytokine-cytokine receptor interactions and ECM-receptor interactions, the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway was also significantly downregulated (Fig. 5E,F). These findings suggest that the expression of key genes facilitates ECM remodeling and affects cell chemotaxis, potentially closely linking them to chemotherapy resistance in OC.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. GO and KEGG analysis of the MEturquoise module. (A) GO enrichment analysis of: biological processes (BP), cellular components (CC), and molecular functions (MF). GO enrichment chord diagrams displaying biological processes (B), cellular components (C) and molecular functions (D). (E) KEGG enrichment analysis. (F) KEGG enrichment chord diagram. GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; ECM, extracellular matrix; NLR, neuroactive ligand-receptor interaction.

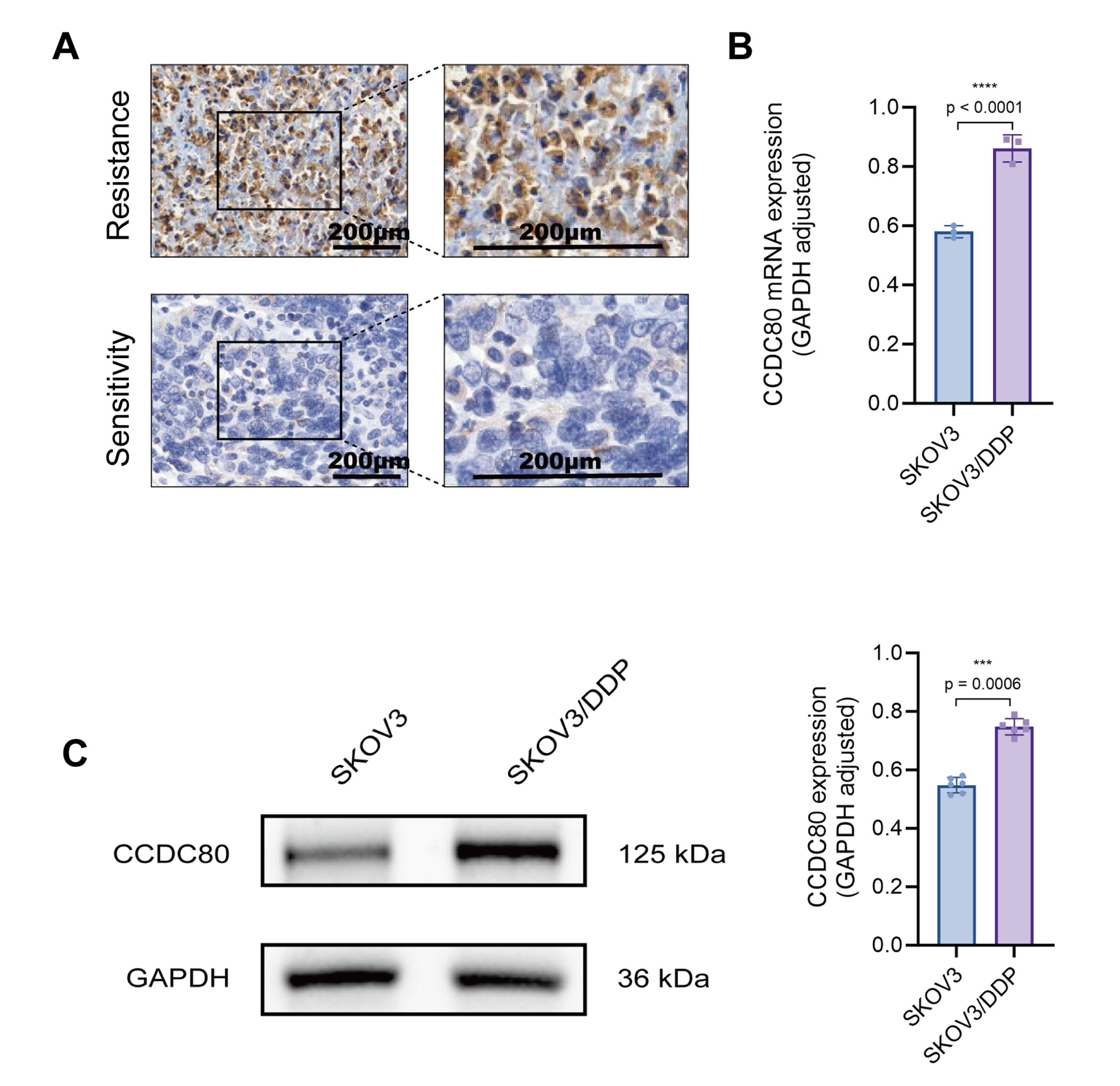

We analyzed the expression pattern of CCDC80 in PROC tissues by comparing its expression levels in two PROC tissue samples with those in four platinum-sensitive OC tissue samples (Supplementary Table 2). The findings revealed a significant elevation of CCDC80 expression in PROC tissues, predominantly localized within the cytoplasm and cell membrane (Fig. 6A). Subsequent validation using cisplatin-resistant SKOV3 cells (SKOV3/DDP) demonstrated a marked upregulation of CCDC80 expression at the level of both mRNA and protein (Fig. 6B,C).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6. Validation of CCDC80 expression in clinical samples and cell lines. (A) Immunohistochemical detection of CCDC80 in platinum-resistant and platinum-sensitive ovarian cancer tissues. (B) RT-PCR analysis of CCDC80 mRNA in platinum-sensitive and resistant ovarian cancer cell lines. (C) Western blot of CCDC80 protein in platinum-sensitive and resistant ovarian cancer cell lines. RT-PCR, quantitative reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction; GAPDH, glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase; SKOV3, human ovarian adenocarcinoma cell line; DDP, cisplatin (cis-diammine-dichloroplatinum); *** p

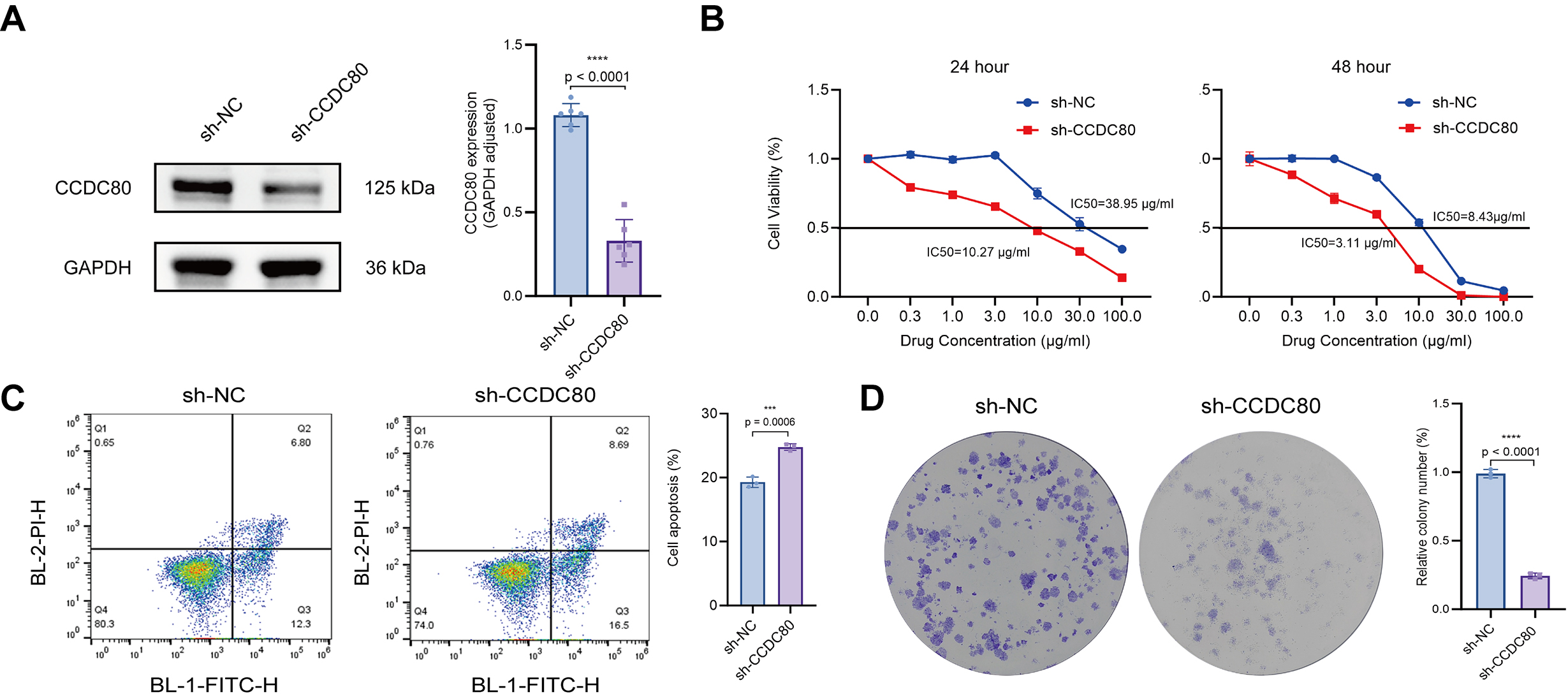

To assess the role of CCDC80 in modulating the sensitivity of OC cells to platinum-based chemotherapy, SKOV3/DDP cells were transfected with CCDC80 shRNA (sh-CCDC80). Western blot analysis confirmed that this treatment induced a marked reduction in CCDC80 protein levels compared to cells transfected with the empty vector negative control (sh-NC) (Fig. 7A). The half-maximal IC50 of cisplatin was measured for both sh-CCDC80 and sh-NC cells, revealing significantly lower IC50 values for the sh-CCDC80 cells at 24 h (10.27 µg/mL, 95% CI: 9.610–10.96) and 48 h (3.11 µg/mL, 95% CI: 2.554–3.768) compared to sh-NC cells (38.95 µg/mL, 95% CI: 31.56–48.90 at 24 h; 8.43 µg/mL, 95% CI: 6.794–10.48 at 48 h) (Fig. 7B). Flow cytometry analysis indicated that knock down of CCDC80 expression induced a significant increase in cisplatin-induced SKOV3/DDP cell apoptosis (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, colony formation assays indicated that suppression of CCDC80 expression substantially increased the sensitivity of SKOV3/DDP cells to cisplatin (Fig. 7D). Overall, the results indicate that reduced CCDC80 expression lowers the resistance of SKOV3/DDP cells to cisplatin.

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7. CCDC80 knockdown reverses cisplatin resistance in SKOV3/DDP cells. (A) Western blot confirms lentivirus-mediated knockdown of CCDC80 expression. (B) IC50 of cisplatin for cells before and after knock-down of CCDC80 expression. (C) Flow cytometric quantification of cell apoptosis following treatment for 24 h with 38 µg/mL cisplatin. Results are shown for cells transfected to knock down CCDC80 expression, and untransfected control cells. (D) Colony-forming ability of untransfected cells and cells transfected to knock down CCDC80 expression, when exposed to 38 µg/mL cisplatin for 24 h. sh-NC, empty vector negative control; IC50, inhibitory concentration; BL-2-PI-H, blue laser detector 2-propidium iodide, height signal detection channel; BL-1-FITC-H, blue laser detector 1-fluorescein isothiocyanate, height signal detection channel. *** p

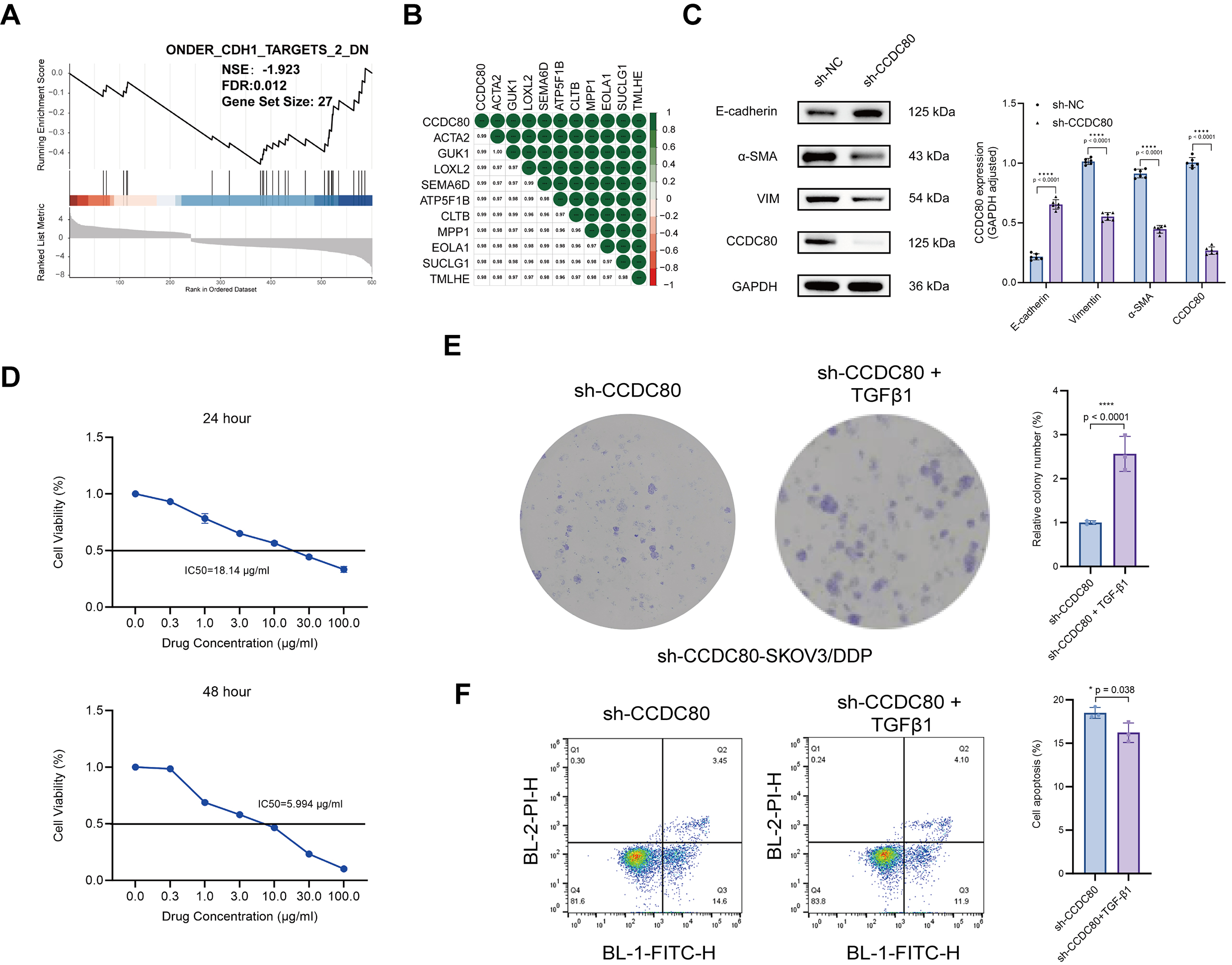

The previous results indicated that CCDC80 plays a role in ECM formation. GSEA utilizing TCGA-OV data demonstrated a negative correlation between the expression of CDH1 (which encodes E-cadherin) and CCDC80 (Fig. 8A). Furthermore, analysis of the GSE15372 dataset revealed a strong positive correlation between CCDC80 and ACTA2 (which encodes

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8. CCDC80 mediates platinum resistance in SKOV3/DDP cells by upregulating EMT. (A) GSEA analysis. (B) CCDC80 gene correlation analysis. (C) CCDC80 knockdown reduces EMT phenotype. (D) Cisplatin IC50 in sh-CCDC80-SKOV3/DDP cells pre- and post-EMT induction. (E) Colony-forming ability of sh-CCDC80-SKOV3/DDP cells treated with 18 µg/mL cisplatin for 24 h, before and after EMT induction. (F) Flow cytometric quantification of apoptosis in EMT-induced and control sh-CCDC80-SKOV3/DDP cells following treatment for 24 h with 18 µg/mL cisplatin. EMT, epithelial-mesenchymal transition; * p

This study is the first focused investigation into the critical role of CCDC80 in mediating platinum resistance in ovarian cancer cells. The findings reveal a significant upregulation of CCDC80 in patient-derived platinum-resistant ovarian cancer, and indicate that in SKOV3/DDP cells enhanced CCDC80 expression increases platinum resistance by stimulating the EMT pathway. These findings provide insights into the molecular mechanisms underlying platinum resistance in ovarian cancer, and identify CCDC80 as a new therapeutic target that offers the potential to avoid OC developing platinum resistance during patient chemotherapy.

CCDC80 was previously classified as a tumor suppressor gene [8, 9, 10, 11]. However, recent research has elucidated its involvement in promoting treatment resistance and immune tolerance in certain malignancies, with some studies suggesting its potential as a prognostic biomarker for adverse outcomes [6, 7, 12]. This study is the first to demonstrate that CCDC80 is significantly upregulated in PROC, strongly correlating with poor patient prognosis.

The increased stemness of tumor cells is a critical factor contributing to chemotherapy resistance in ovarian cancer [13, 14, 15]. EMT is pivotal in modulating tumor stemness [16, 17]. Key transcription factors, including Snail and zinc finger e-box binding homeobox 1 (ZEB1), together with signaling pathways such as Wnt/

Functional enrichment analyses demonstrate that CCDC80 upregulation significantly enhances cellular chemotaxis. Mechanistically, this augmented chemotactic activity facilitates the formation of a dense stromal barrier that substantially impedes drug penetration—a phenomenon that aligns precisely with CCDC80’s established role in ECM organization [22, 24]. Moreover, we also showed that CCDC80 upregulation mediates downregulation of the PI3K-AKT signaling pathway, which promotes chemotherapy resistance by enhancing cell survival, inhibiting apoptosis, and modulating the tumor microenvironment [25, 26, 27]. One possible explanation for the CCDC80-induced downregulation of PI3-AKT activity is that, when exposed to platinum, tumors may adapt by relying on alternative survival mechanisms, such as those provided by the MAPK or JAK-STAT pathways [28, 29, 30]. The redundancy in survival pathways underscores the complexity of resistance mechanisms and highlights the need to explore their interactions. Furthermore, reduced PI3K-AKT activity could provide a metabolic advantage to platinum-resistant cells. Given that PI3K-AKT regulates glucose metabolism and anabolic processes, its suppression might drive resistant cells to adopt a more energy-efficient metabolic phenotype, such as increased reliance on oxidative phosphorylation, enabling them to better survive chemotherapy-induced stress [31, 32, 33, 34].

The emergence of drug resistance is a substantial clinical obstacle to the use of platinum-based chemotherapeutic agents, which are the cornerstone of OC treatment. Reinforcing the clinical importance of platinum resistance, BRCA1/2 germline mutations are the strongest known genetic risk factor for epithelial OC and occur in 6–15% of patients — these mutations confer enhanced platinum sensitivity and result in superior survival outcomes, despite typically later-stage and higher-grade diagnosis [34, 35]. The development of specific and potent inhibitors targeting CCDC80, alongside the refinement of delivery systems, such as nanoparticle-based platforms, may offer a novel therapeutic approach to counteract drug resistance [7, 36, 37]. Moreover, CCDC80 expression levels could potentially serve as biomarkers for predicting the efficacy of platinum-based chemotherapy, thereby establishing a basis for personalized treatment strategies [6, 12, 38].

While this study significantly advances our understanding of the role of CCDC80 in mediating platinum resistance in OC, several limitations remain, and warrant further investigation. First, the precise molecular mechanisms by which CCDC80 regulates EMT, particularly its downstream signaling and interactions with TGF-

This study is the first to demonstrate that (i) CCDC80 expression is increased in platinum-resistant patient OC, correlating with unfavorable patient prognosis, and (ii) in SKOV3/DDP OC cells, CCDC80 promotes platinum resistance by activating the EMT pathway. These findings implicate CCDC80 as a potential therapeutic target, and may ultimately lead to the development of new treatments to improve the survival rates of OC patients.

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

LX, LZ and YC designed the research protocol and established the analytical methodology. LX performed the molecular experiments. YW conducted the immunohistochemical assays. LX led the bioinformatics analysis. LZ and XJ assisting in data visualization. YC, the Principal Investigator, secured funding and resources and oversaw the research with critical review. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Zhongda Hospital Affiliated to Southeast University, Nanjing, China; (approval number: 2019ZDSYLL021-P01). Waiver of informed consent was granted by the ethics committee due to the retrospective and anonymized nature of the study.

We express our gratitude to Professor Pingsheng Chen from the Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Southeast University, for providing access to laboratory facilities and offering technical guidance throughout this study. Additionally, we acknowledge Dr. Hui Xu from the Department of Immunology, School of Medicine, Southeast University, for generously providing the SKOV3 and SKOV3/DDP cell lines.

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81872122).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/CEOG39988.

During the preparation of this work, the authors employed DeepSeek and ChatGPT to assist with language polishing and expression refinement. Following the use of these tools, the authors thoroughly reviewed and edited the content as necessary, and assumes full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the published material.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.