1 Department of Gynecology, Women’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, 310006 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

2 Department of Obstetrics, Women’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, 310006 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

3 Department of Gynecology, The Fourth Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, 322000 Yiwu, Zhejiang, China

Abstract

The impact of pregnancy on the pelvic floor is not yet fully understood. This study aimed to investigate pelvic organ displacement during pregnancy and identify its key influencing factors.

This retrospective case-control study analyzed 238 pregnant women (gestational age range: 12–41 weeks) and 238 age-matched (±1 year) non-pregnant controls. All participants underwent pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) at two hospitals during the same hospitalization period. Distances from the bladder neck (BN), cervix (C), and posterior fornix (PF) to the pubococcygeal line (PCL) were measured using MRI. These distances were compared between pregnant and non-pregnant groups. Pregnancy-related “inferior” or “superior” positions were classified using thresholds derived from the non-pregnant group (mean ± 1.96 standard deviations [SD]). Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were performed to identify factors independently associated with positional deviations in the pregnant group.

The mean gestational age of the pregnant group was 32.3 ± 5.8 weeks. Compared with controls, pregnant women exhibited inferior BN (19.2 ± 6.1 vs. 23.3 ± 4.3 mm, p < 0.001) and C positions (19.1 ± 7.8 vs. 21.6 ± 5.3 mm, p < 0.001), but superior PF positions (42.3 ± 10.5 vs. 31.7 ± 8.1 mm, p < 0.001). In univariate analyses, the fetal engagement depth was significantly associated with positional changes in all pelvic organs (p < 0.001 for all). After adjusting for confounders, a fetal engagement depth of ≥40 mm was independently associated with increased odds of inferior BN (odds ratio [OR] = 5.04, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.59–16.01, p = 0.006) and C (OR = 11.46, 95% CI 2.53–51.92, p = 0.002) positions, whereas a depth of <20 mm predicted superior PF positioning (OR = 12.24, 95% CI 4.82–31.11, p < 0.001). Additionally, the presence of a low-lying placenta (OR = 2.96, 95% CI 1.18–7.39, p = 0.020) or placenta previa (OR = 2.70, 95% CI 1.29–5.64, p = 0.008) was significantly associated with superior PF position.

This study demonstrates that pregnant women exhibit significant positional alterations in pelvic organ anatomy. Notably, fetal engagement depth emerged as a robust biomechanical correlate of these anatomical changes.

Keywords

- fetal engagement

- pelvic floor anatomy

- pelvic organ prolapse

- placenta previa

- pubococcygeal line

Pregnancy-induced pelvic floor dysfunction—including urinary incontinence and pelvic organ prolapse—affects nearly half of women during gestation, with many cases persisting postpartum. This condition imposes substantial physical and psychological burdens [1, 2, 3, 4]. While vaginal delivery is a major risk factor for pelvic floor dysfunction [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9], emerging evidence suggests that anatomical changes during pregnancy may independently contribute to pelvic floor injury. One review found that pregnancy is associated with bladder neck lowering, increased bladder neck mobility, pelvic organ descent, decreased levator ani strength, and reduced urethral resistance [3].

Theoretically, hormonal changes and mechanical pressure from the gravid uterus can cause significant alterations in pelvic support structures during pregnancy. As the uterus changes position within the pelvis over the course of gestation, the pressure it exerts on the pelvic floor likely changes as well. In the first trimester, as the uterus begins to enlarge, its increasing weight starts to press on the pelvic floor. Eventually, the uterus becomes too large to remain entirely within the pelvis and gradually rises out of it. Clinically, pregnancy is strongly associated with urinary incontinence [9], yet pelvic organ prolapse during pregnancy remains rare [10, 11]. This discrepancy suggests that pregnancy-related pelvic organ displacement does not follow a simple gravitational descent model.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) offers superior soft tissue contrast and a comprehensive view of the pelvis, making it a valuable tool for studying pelvic floor anatomy [12]. However, concerns about fetal safety [13] have limited its use in pregnant populations to small cohorts (1–56 participants) [14, 15, 16, 17]. Few studies have quantified how obstetric factors, such as fetal engagement depth and placental location, affect pelvic organ displacement. Our two tertiary teaching hospitals have collected a large number of MRI scans from pregnant patients. Using this dataset, our study aims to reassess pelvic organ positions and explore factors associated with their positional changes.

An electronic search of the radiology information system from July 2018 to June 2019 was performed in two hospitals, and 3473 inpatients underwent pelvic MRI. Then, the electronic medical records were reviewed. In all, 308 were pregnant women, 70 cases of which were excluded, and 238 cases were enrolled in the final analysis. Controls were first matched to cases based on: hospitalization period (same time frame to minimize temporal bias) and Age (

Exclusion criteria of pregnant women were as follows: (1) a history of pelvic organ prolapse (POP) or urinary/fecal incontinence; (2) any mass or cyst in the cervix or the cervical canal with a diameter

Controls were women with a normal uterus and no POP indicated by the gynecological examination record [18]. Exclusion criteria of controls were as follows: (1) any exclusion criterion for pregnant cases; (2) presence of POP on gynecological examination; (3) enlarged uterus with a maximum diameter

In our two hospitals, pelvic MRIs were performed using a 1.5 Tesla magnet (Sigma, General Electric Medical System, Milwaukee, WI, USA) with patients in a lying position. The MRI measurements were performed on the (near-) midline sagittal plane by an experienced gynecologist-obstetrician and radiologist, using the Web-viewer (Version 1.0.0.53449, Greenlander Information Technology, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion. The sequences reviewed in this study were fat-saturated T2-weighted fast recovery fast spin-echo, T2-weighted single-shot fast spin-echo, or two-dimensional (2D) fast imaging employing the steady-state acquisition technique.

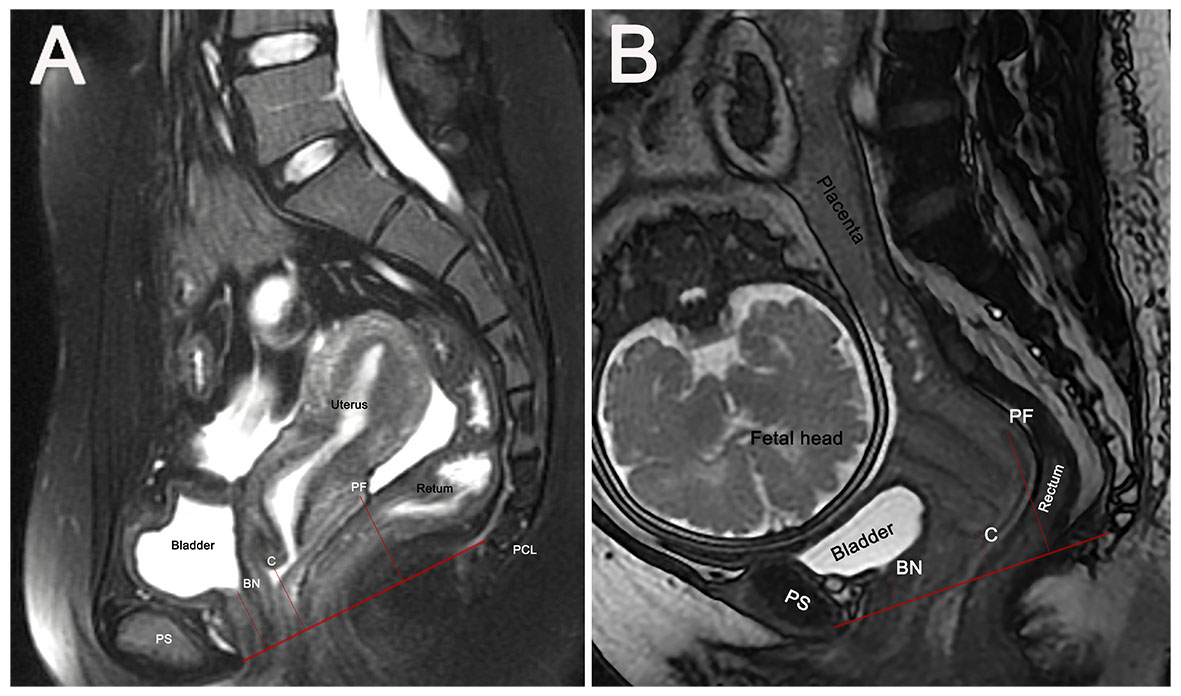

The pubococcygeal line (PCL), the recommended MRI reference line for diagnosing POP, extends from the pubic symphysis’s inferior aspect to the last coccygeal joint [19]. Perpendicular distances from the PCL to the bladder neck (BN), the cervix’s most distal edge (C), and the posterior fornix’s apex (PF) were measured (Fig. 1). Organ-specific reference points above the PCL had positive values (+), while those below had negative values (–).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Sagittal MRI-based measurement of pelvic organ positions relative to the pubococcygeal line (PCL). PCL is the red line from pubic symphysis to the last coccygeal joint. Perpendicular distances from the PCL to anatomical points BN, C, and PF are measured (denoted by short red lines) in non-pregnant women (A) and pregnant women with cephalic presentation (B). BN, bladder neck; C, most distal cervical edge; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; PF, apex of the posterior fornix; PS, pubic symphysis.

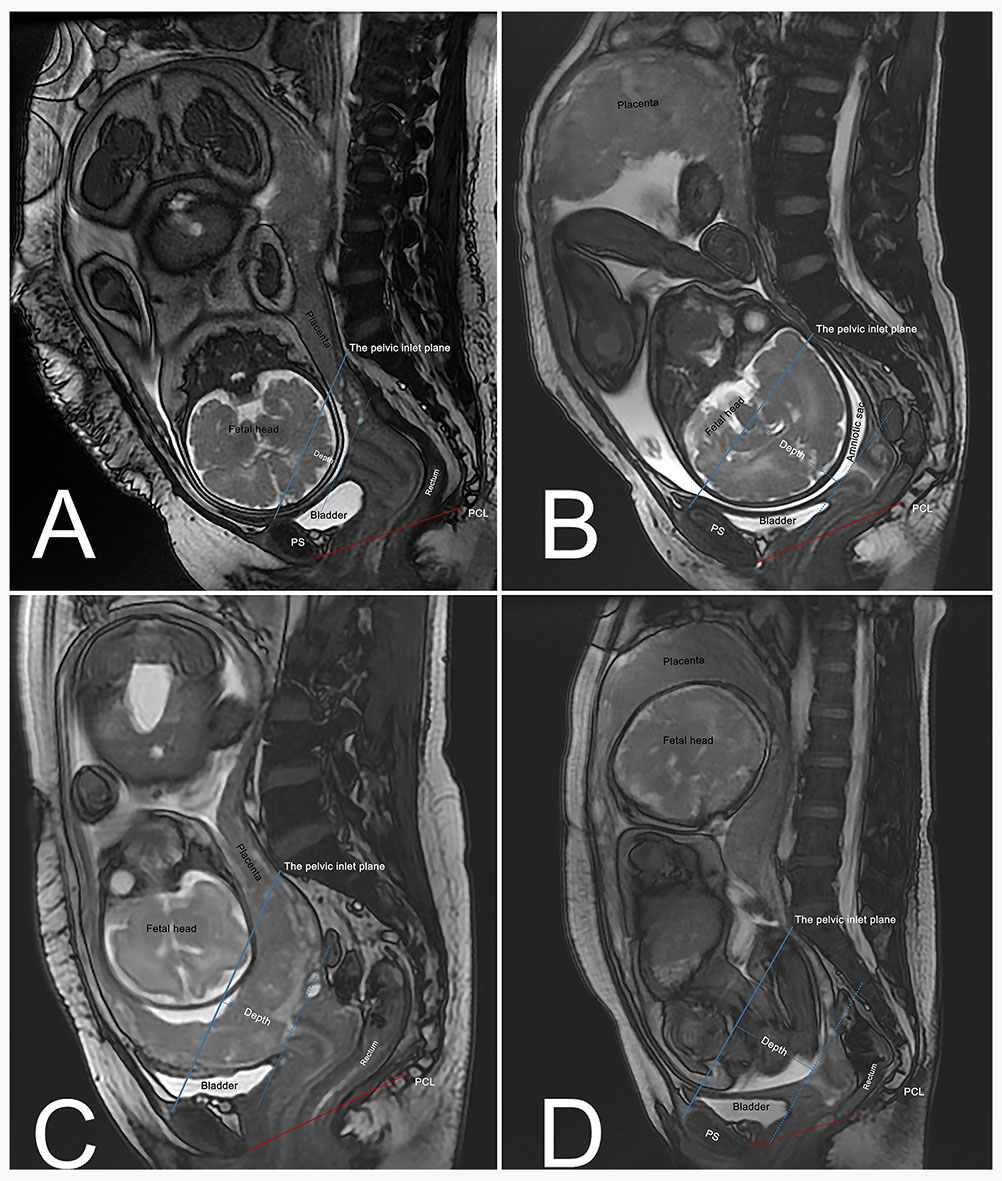

An additional line drawn from the pubic symphysis’ superior margins to the sacral promontory defines the pelvic inlet plane for pregnant women [20]. The depth of the fetus and its appendages in the pelvis was defined as the greatest distance from the pelvic inlet plane to the fetal presentation or the inferior part of the placenta or amniotic sac (Fig. 2). All measurements were performed in millimeters.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Engagement depth of fetal/placental structures relative to pelvic inlet plane. (A) Cephalic presentation with shallow engagement (Depth = 22 mm). (B) Cephalic presentation with deep engagement (Depth = 65 mm; amniotic sac as the most inferior part entering the pelvis). (C) Placenta previa (Depth = 40 mm; placenta as the most inferior part entering the pelvis). (D) Breech presentation (Depth = 60 mm; amniotic sac as the most inferior part entering the pelvis). Blue solid line: Pelvic inlet plane, drawn from the superior margin of the pubic symphysis to the sacral promontory. Blue dashed line: Parallel to the pelvic inlet plane, passing through the lowest point of the fetus or its associated structures. Depth: Perpendicular distance between the two parallel lines, quantifying the extent of fetal/placental descent into the pelvis. Red solid line: Pubococcygeal line (PCL).

Descriptive variables, including baseline data and MRI measurements, were reported as percentages (n (%)), medians (interquartile range), and means

The average gestational age of the 238 pregnant women was 32.3

There was no significant difference in age at the time of MRI between the two groups (32.2

| Variables | Pregnant group | Control group | OR (95% CI) | p value |

| (n = 238) | (n = 238) | |||

| Age, mean (SD), years, | 32.2 (5.1) | 32.2 (5.3) | 1.00 (0.96–1.03) | 0.909 |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 25.7 (3.5) | 21.8 (3.6) | 0.73 (0.69–0.78) | |

| Height, mean (SD), cm | 159.3 (4.9) | 160.3 (5.4) | 1.04 (1.01–1.08) | 0.031 |

| Parity, median (IQR) | 1 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.60 (0.44–0.80) | |

| Number of VDs, median (IQR) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 1.30 (0.86–1.97) | 0.211 |

| Number of CDs, median (IQR) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0.48 (0.34–0.66) | |

| Length of PCL, mean (SD), mm | 100.5 (8.4) | 100.6 (8.8) | 1.00 (0.98–1.02) | 0.895 |

| BN-PCL, mean (SD), mm | 19.2 (6.1) | 23.3 (4.3) | 1.16 (1.12–1.21) | |

| C-PCL, mean (SD), mm | 19.1 (7.8) | 21.6 (5.3) | 1.06 (1.03–1.09) | |

| PF-PCL, mean (SD), mm | 42.3 (10.5) | 31.7 (8.1) | 0.88 (0.86–0.91) |

MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; SD, standard deviation; BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; VD, vaginal delivery; CD, cesarean delivery; PCL, pubococcygeal line.

BN-PCL, C-PCL, and PF-PCL: vertical distances from the bladder neck, cervix, and posterior fornix to PCL, respectively.

Among the 238 pregnant women studied, 53 (22.3%) were identified with an “inferior” BN position, indicated by values lower than 14.87 mm. Additionally, 39 (16.4%) exhibited an “inferior” C position with values lower than 11.21 mm, and only one (0.42%) had an “inferior” PF position, with values below 15.82 mm. In contrast, 71 (29.8%) cases showed a “superior” PF position with values exceeding 47.58 mm.

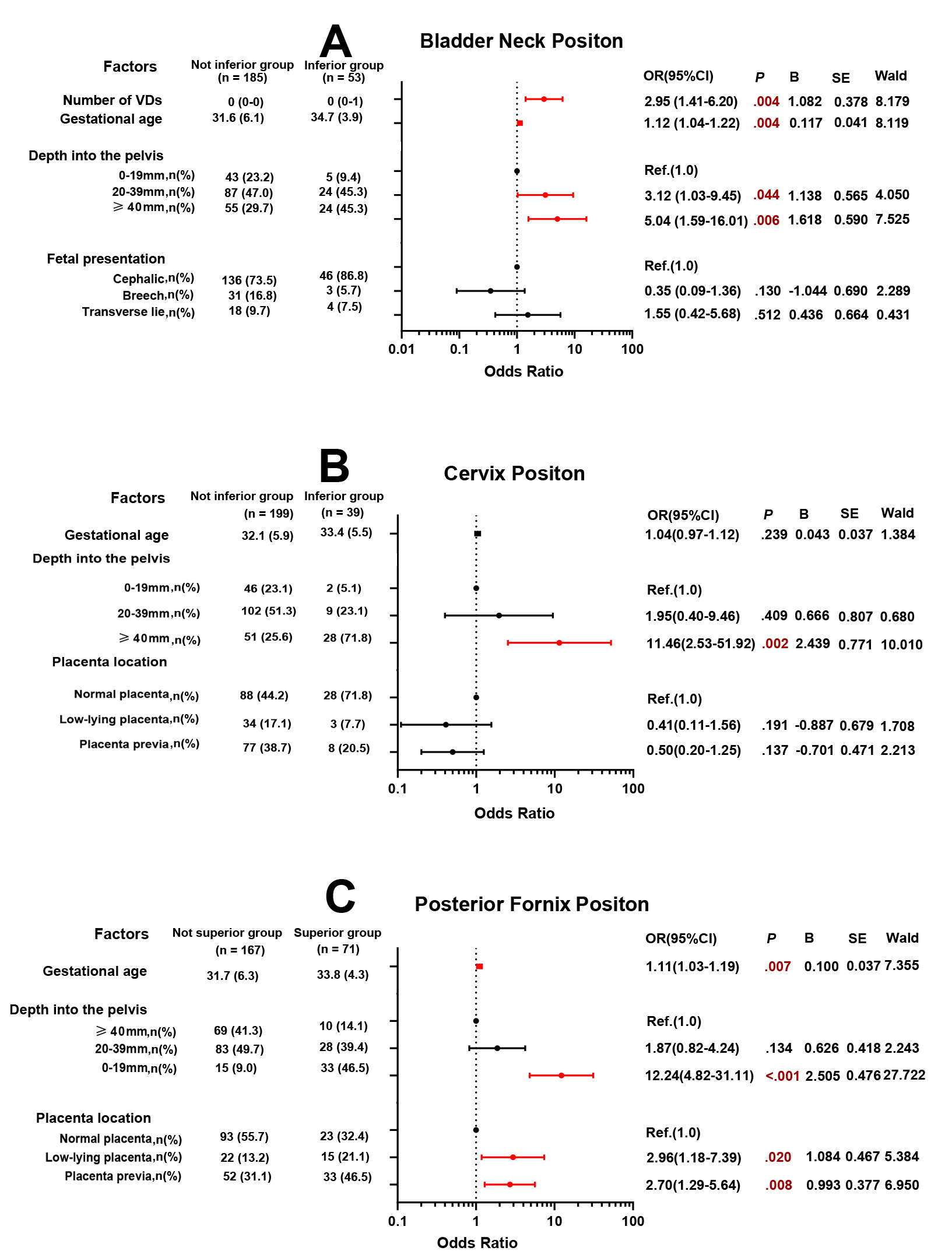

Univariate analysis indicated that greater gestational age, deeper depth of the fetus and its appendages in the pelvis, and an increased number of vaginal deliveries were potentially associated with an “inferior” BN position (Supplementary Table 2). Multivariate logistic regression (Fig. 3A) showed that with each additional week of gestational age, the odds of an “inferior” BN position increase by 12% (p = 0.004). And an “inferior” BN position was found in 45.3% of women with entering pelvis depth

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Multivariable logistic regression analysis of pelvic organ positions. In the multivariate logistic regression model for bladder neck (A), the Hosmer-Lemeshow test yielded

Univariate analysis found that a deeper depth of the fetus and its appendages in the pelvis was positively associated with an “inferior” C position; the presence of a low-lying placenta and placenta previa was inversely related (Supplementary Table 3). However, multivariate logistic regression (Fig. 3B) showed that an “inferior” C position occurred in 71.8% of women with a depth of the fetus and its appendages in the pelvis

Univariate analysis showed that a higher BMI, advanced gestational age, deeper depth of the fetus and its appendages entering the pelvis, and the presence of a low-lying placenta or placenta previa were associated with a “superior” PF position (Supplementary Table 4). Multivariate logistic regression (Fig. 3C) revealed that with each additional week of gestational age, the odds of a “superior” PF position increase by 11% (p = 0.007). Moreover, a “superior” PF position occurred in 46.5% of women with entering pelvis depth

This study presents a large MRI-based analysis of pelvic organ positional changes during pregnancy (n = 238), revealing distinct shifts relative to non-pregnant reference thresholds. Specifically, the BN and C showed inferior displacement, while the PF exhibited superior elevation. Fetal engagement depth was strongly associated with positional variations across all pelvic organs. A depth of

Pregnancy is consistently associated with descent of pelvic organs [21]. In this study, the pregnant group showed inferior positioning of the BN and C, consistent with previous research [21], although with a modest reduction of 2.5–4.1 mm. Notably, the PF was superior in the pregnant group—an original finding not previously reported. Key factors associated with positional variation included the following.

First, gestational age (GA) was a significant factor. Compared with the non-pregnant group, the pregnant group had higher BMI values (25.7 vs. 21.8 kg/m2). However, PF was superior in the pregnant group. Of note, the mean BMI in the pregnant group was only slightly above the threshold for overweight. In the multicollinearity analysis, BMI was found to be correlated with GA, likely reflecting pregnancy-related weight gains due to uterine expansion and fetal growth. So, we included only GA in the final analysis. And we found that the BN position descended progressively with advancing pregnancy, whereas the C position did not show a significant association with GA. By contrast, PF elevation increased significantly with GA. Prior ultrasound studies suggest that the vaginal axis shifts upward and posteriorly as pregnancy progresses, which may support our findings [22]. Because pre-pregnancy BMI data were unavailable due to the retrospective nature of our study, future research incorporating pre-pregnancy BMI could offer more nuanced insights.

Fetal engagement depth emerged as a critical correlational factor, independent of GA. Women with deeper fetal engagement (

We also examined fetal presentation and placental location. While breech presentation and placenta previa were initially associated with inferior BN and C positions, these associations lost significance after adjusting for confounders. However, a low-lying placenta and placenta previa remained significant predictors of superior PF elevation (OR = 2.96 and OR = 2.70, respectively). Given that 51.3% of our sample had these conditions, they likely contributed to the observed superior PF elevation.

Vaginal delivery history was positively associated with BN descent, consistent with prior studies on post-childbirth pelvic floor dysfunction [1, 3, 16, 23]. However, no significant association was found between vaginal delivery history and C or PF positioning, possibly because of confounding factors or characteristics of the study population.

Finally, maternal posture during MRI is another critical, though often overlooked, factor influencing pelvic floor measurements. While most MRIs in our hospitals are performed in the supine position, lateral decubitus positioning may be used in later pregnancy to avoid fetal distress. Because this was a retrospective study, we lacked precise data on patient positioning during scans. Previous pelvic floor imaging studies have used varied postures. For example, Chan et al. [21] used ultrasound in the supine position, and Oliphant et al. [22] used ultrasound in the lithotomy position. Routzong et al. [15, 16] conducted MRI studies in the lateral decubitus position for gravid patients, while Yagi et al. [17] performed MRIs in the supine position at rest. These differences in imaging posture can affect the pelvic load distribution [24], highlighting an important area for further investigation.

Overall, our study underscores the importance of a comprehensive approach when assessing pelvic anatomy during pregnancy. Factors such as GA, fetal engagement depth, fetal presentation, and placental location must all be considered. Because pelvic organ positioning likely differs between upright and lying postures—and both are physiologically relevant—future research should also investigate pelvic anatomy in standing positions. Our study offers new perspectives and valuable insights into evaluating pelvic floor anatomy during pregnancy.

Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, because of potential teratogenic risks, MRI was not performed during the first trimester. Second, because this was a retrospective study, causality cannot be definitively established, and the identified associations should be interpreted with caution. Third, selection bias may arise from the restriction of our sample to pregnant women undergoing clinically indicated MRI, and stringent inclusion/exclusion criteria. Furthermore, the single-center design with limited ethnic diversity may constrain generalizability to broader pregnant populations. Fourth, the wide confidence intervals of the odds ratios for some factors reflect limited sample sizes in the subgroup analysis. Fifth, the pelvic floor is a three-dimensional structure, and two-dimensional measurements or single reference lines may not fully capture its anatomical changes during pregnancy. Future research should include prospective, large-scale studies across diverse racial and cultural groups to improve generalizability. More representative markers for the posterior compartment, such as the anorectal angle, the use of pelvic inclination correction system [25] and three-dimensional MRI are also recommended. Additionally, incorporating intra- and inter-observer variability assessments would enhance measurement reliability—an acknowledged limitation of this study.

Despite these limitations, the study has several strengths. We systematically explored pelvic organ positional variations in relation to obstetric factors—a novel approach in this field. While an ideal study design would involve serial MRIs before and throughout pregnancy, such an approach raises ethical concerns due to repeated MRI exposure. This study provides a large-scale dataset that offers important insights into pelvic floor changes during pregnancy. To define “inferior” or “superior” organ positions, we established reference thresholds based on a large non-pregnant control group, enhancing the robustness and clinical relevance of our findings.

This MRI-based study demonstrates that pregnancy-related pelvic organ displacement may not conform to simplistic gravitational descent models. Changes in pelvic organ positioning during pregnancy are associated with multiple factors, particularly obstetric variables.

The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author, Xiaofeng Zhao, upon reasonable request.

FL: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Writing-original draft. YOY: Data curation, Software, Visualization, Writing-review & editing. YZ: Formal analysis, Validation, Resources, Writing-review & editing. RW: Investigation, Resources, Writing-review & editing. XZ: Supervision, Funding acquisition, Project administration, Writing-review & editing. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Fourth Affiliated Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University (approval number: No. K20190046). The requirement for informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study and the use of fully anonymized data.

We are very grateful to Dr. Weizeng Zheng, Department of Radiology, Women’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, for his warm help reviewing the magnetic resonance images.

The Basic Public Welfare Research Project of Zhejiang Province (Project No: LGF22H040018), a nonprofit organization, provided financial support for this project.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/CEOG39513.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.