1 Medical Department, Queen Mary School, Nanchang University, 330031 Nanchang, Jiangxi, China

2 Second Clinical Medical College, Second Affiliated Hospital of Xi’an Jiaotong University, 710004 Xi’an, Shaanxi, China

3 Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Zibo Municipal Hospital, 255400 Zibo, Shandong, China

4 Jiangxi Medical College, Nanchang University, 330006 Nanchang, Jiangxi, China

5 School of Life Sciences, Nanchang University, 330031 Nanchang, Jiangxi, China

6 Clinical Laboratory, Key Laboratory of Jingdezhen for Cellular and Molecular Medicine, The Second People’s Hospital of Jingdezhen, 333000 Jingdezhen, Jiangxi, China

7 Department of Obstetrics & Gynecology, The Second People’s Hospital of Jingdezhen, 333000 Jingdezhen, Jiangxi, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) is a rare obstetric complication associated with high maternal morbidity and mortality. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the key pathophysiological mechanisms, current therapeutic strategies, and emerging interventions for AFE, with the goal of reducing maternal mortality and improving clinical outcomes.

AFE results from the entry of amniotic fluid components into the maternal circulation, triggering a cascade of complex and poorly understood pathophysiological events. These include immune system activation, cardiopulmonary dysfunction, and coagulopathy.

The incidence of AFE ranges from approximately 1.9 to 6.1 cases per 100,000 births. Due to the lack of definitive diagnostic criteria and incomplete understanding of its underlying mechanisms, AFE remains challenging to diagnose and manage. Current treatment strategies primarily focus on supportive care.

AFE poses significant challenges in both diagnosis and management. This article underscores the limitations of current research and the obstacles encountered in clinical practice. Improving our understanding of AFE holds the potential to enhance treatment strategies and patient outcomes.

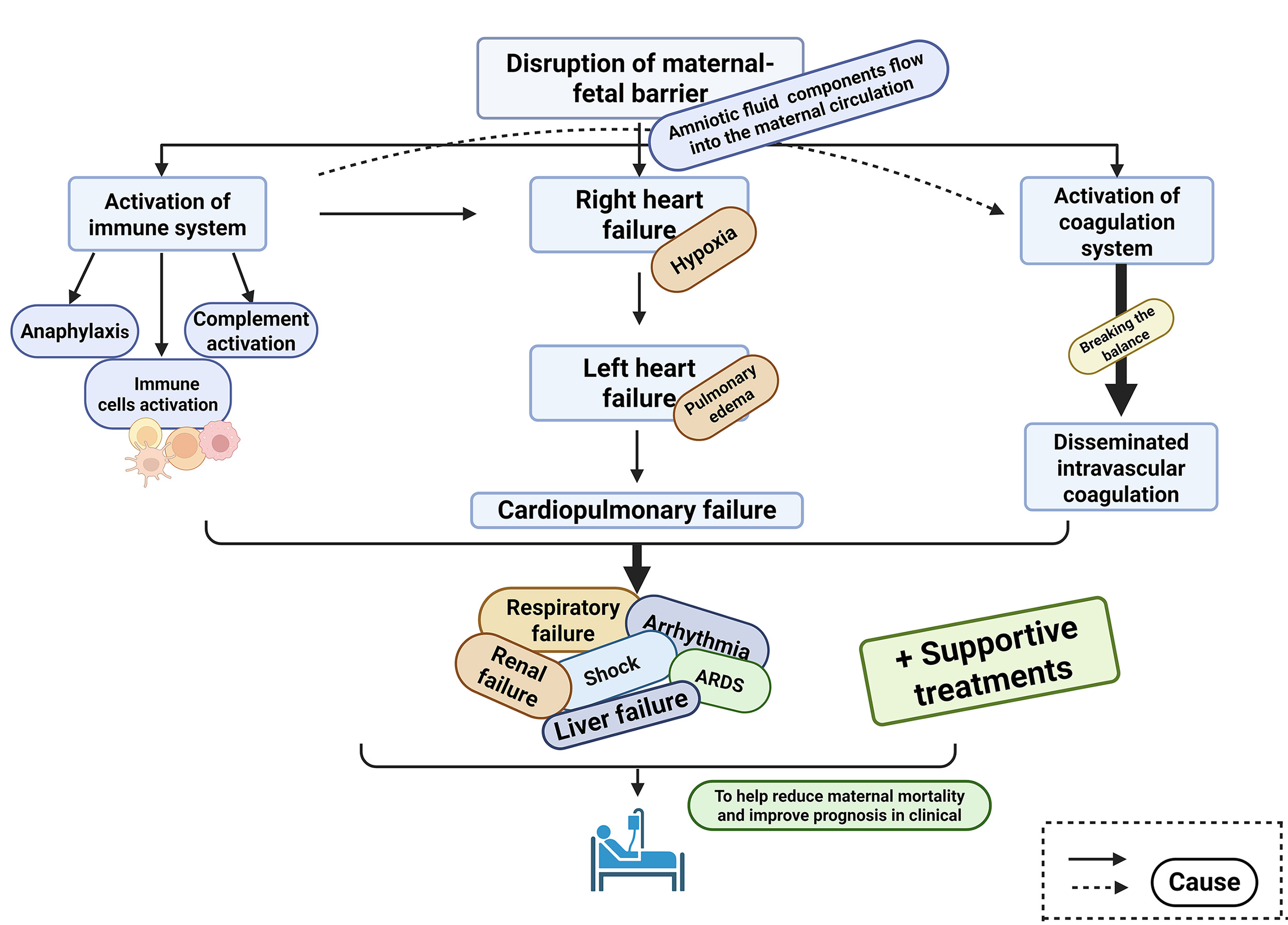

Graphical Abstract

Keywords

- amniotic fluid embolism

- disseminated intravascular coagulation

- cardiopulmonary failure

- immune system activation

Amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) is a rare but critical intrapartum complication characterized by sudden onset and high maternal mortality. The estimated incidence ranges from 1.9 to 6.1 cases per 100,000 births, though this figure is likely underestimated due to diagnostic challenges and underreporting [1]. According to the 2023 Statistical Bulletin on China’s Health Development, the maternal mortality rate declined from 15.7 per 100,000 live births in 2022 to 15.1 per 100,000 in 2023; however, the overall situation remains concerning [2]. AFE was the second leading cause of maternal mortality in Slovakia, accounting for 11.0% of all maternal deaths [3]. Notably, around 70% of AFE cases occur during vaginal delivery, and the maternal mortality rate can escalate to 60% within 1 to 12 hours following onset [4].

Since the first documented case of AFE in 1926, understanding of the condition has evolved from Steiner and Lushbaugh’s 1941 hypothesis attributing it to mechanical obstruction in the maternal circulation, to Clark’s 1995 theory suggesting an anaphylactoid-like reaction as the underlying mechanism [5, 6]. Despite ongoing research, major gaps remain in the understanding of AFE pathophysiology, posing substantial challenges to effective clinical management. Gaining deeper insights into the pathological mechanisms of AFE is essential for developing targeted preventive strategies, improving diagnostic accuracy, and enhancing therapeutic outcomes, ultimately aiming to reduce maternal mortality.

After the 1995 study by Clark et al. [5], which identified the pathophysiological process of AFE as resembling an anaphylactoid reaction, this view has gained widespread acceptance and has since served as a foundation for additional hypotheses [6]. Current research suggests that activation of the maternal immune system triggered by components within the amniotic fluid—is a key initiating event. This includes immune cell activation, complement system involvement, and anaphylactic responses [6]. In addition, cardiopulmonary failure and abnormal coagulation function during the pathophysiological process are also important causes of maternal death [1, 7].

However, due to the condition’s complexity and the difficulty in collecting comprehensive case data, most existing studies examine isolated aspects of AFE pathogenesis. As a result, the research is fragmented and lacks continuity, with few studies offering a thorough and integrated analysis of the underlying mechanisms. Despite advancements in medical care, the mortality rate associated with AFE has only slightly declined. This limited progress is primarily due to the condition’s highly variable clinical presentation, complex pathophysiology, and sudden onset. Consequently, most treatment strategies remain supportive and symptomatic, with outcomes largely dependent on the timeliness and effectiveness of maternal care [8].

This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the key factors involved in the pathophysiological mechanisms of AFE, drawing from recent literature. Based on these mechanisms, it also reviews current therapeutic approaches and explores potential treatment candidates. Furthermore, the article discusses the limitations of existing pathophysiological research and the ongoing challenges in clinical management. The goal is to contribute to the development of clearer diagnostic criteria and effective preventive strategies, ultimately aiming to reduce maternal mortality and improve patient outcomes.

In 1941, Steiner et al. [9] suggested that AFE resulted from a mechanical obstruction caused by fetal material entering the maternal circulation. However, later study has shown that the presence of amniotic fluid and fetal components in the maternal bloodstream triggers severe pulmonary vasoconstriction and bronchoconstriction [10]. These reactions are primarily driven not by physical blockage but by the response of the maternal immune system, which involves the release of inflammatory mediators [10]. These inflammatory factors further activate the coagulation and fibrinolytic systems, often leading to disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), which can result in severe maternal hemorrhage and, ultimately, death [11].

Amniotic fluid can contain fetal hair, skin cells, intestinal mucin, free fetal nucleic acids, as well as various vasoactive and procoagulant substance [1, 12]. If the barrier between the maternal circulation and the amniotic fluid is compromised, these components can enter the maternal bloodstream, triggering an immune response that may lead to complications associated with significant morbidity and mortality [13].

Cellular and humoral immune responses can be triggered by pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) or damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs). PAMPs include microbial components such as nucleic acids and lipoproteins, while DAMPs are typically released from damaged or necrotic cells [14]. In the majority of clinical scenarios, AFE presents as a sterile condition, so it is more widely accepted that DAMPs (rather than PAMPs) play a predominant role in the pathophysiology of AFE [15]. Once immune cells are activated, they release large amounts of proinflammatory cytokines, including tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-

As early as 1956, Attwood [19] proposed that anaphylactoid reactions might be involved in the pathophysiology of AFE. However, it was not until 1995 that Clark et al. [5] conducted a detailed analysis, highlighting significant similarities in hemodynamic changes and clinical progression between AFE and anaphylactoid reactions. In a significant amount of literature, anaphylactic reactions and anaphylactoid reactions are collectively termed anaphylaxis [18]. Although both reactions present with similar clinical features, anaphylactoid reactions are distinguished by the direct activation of mast cells through non-immunoglobulin E-mediated mechanisms, bypassing the need for prior sensitization [20]. In their article, Yang et al. [6] further suggested that true anaphylactic reactions might also contribute to the pathophysiology of AFE. In cases of multiple pregnancies, previous exposure to fetal antigens could sensitize the maternal immune system, allowing immunoglobulin E-mediated anaphylactic responses upon re-exposure [6]. Despite the plausibility of this hypothesis, direct clinical evidence confirming a classical immunoglobulin E-mediated anaphylactic mechanism in AFE remains limited. In both anaphylactic and anaphylactoid reactions, mast cells and basophils undergo degranulation, releasing mediators such as histamine, leukotrienes, and tryptase, which increase vascular permeability and trigger a cascade of harmful physiological effects [20]. Among these mediators, elevated serum tryptase levels have occasionally been detected in AFE patients, lending some clinical support to mast cell involvement, though findings remain inconsistent.

The involvement of complement activation in the pathophysiology of AFE was first proposed by Hammerschmidt et al. [21] in 1984, based on a case involving a 30-year-old woman who died from extensive pulmonary microvascular leukocyte stasis shortly after undergoing a cesarean hysterectomy. Benson et al. [22] detected abnormally low C3, C4 levels in eight women with AFE. Additionally, Fineschi et al. [23] observed C3a expression and mast cell degranulation in the bronchial walls of AFE patients. These findings provide more consistent pathological and biochemical evidence supporting complement activation as a relevant mechanism in AFE. The reduced levels of C3 and C4 imply activation of the classical complement pathway, though activation via the alternative pathway cannot be excluded [12, 21]. During complement activation, the fragments C3a and C5a play key roles in promoting mast cell degranulation by binding to specific receptors on mast cells. Complement activation also contributes to the broader activation of immune cells, further amplifying the inflammatory response. Unlike immunoglobulin E-mediated anaphylaxis, this complement-mast cell axis is supported by both clinical biomarkers and histological evidence, suggesting it may represent a more validated mechanistic pathway in AFE.

From the above analysis, it is clear that complement activation, anaphylaxis, and broader immune system activation are all implicated—at least to some extent—in the pathophysiology of AFE (The three processes involved in immune system activation in AFE are shown in Fig. 1). When the maternal-fetal barrier is compromised and amniotic fluid enters the maternal circulation, certain unidentified factors can trigger an immune response. This activation of the maternal immune system leads to the release of a large array of inflammatory mediators, resulting in tissue injury and organ dysfunction. Various pathological processes may then act synergistically on the already vulnerable mother, either during or before delivery, ultimately affecting her overall health and potentially her survival. Although the involvement of the immune response in the pathogenesis of AFE is increasingly recognized, many critical aspects remain unresolved. The precise triggers of immune activation, the specific mediators involved, the underlying mechanisms, and the connection between mast cell degranulation and complement activation are still poorly understood. It is clear that clinicians and researchers face a complex and challenging task in fully uncovering these mechanisms and improving clinical outcomes for AFE.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The three processes involved in immune system activation in AFE. The figure illustrates three major mechanisms contributing to immune activation: (1) recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) by pattern recognition receptors (PRRs); (2) activation of immune cells including natural killer (NK) cells; and (3) downstream release of inflammatory mediators such as reactive oxygen species (ROS), nitric oxide (NO), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), interleukins (ILs), and interferons (IFNs). These processes may lead to systemic complications such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), and prostaglandin (PG)-mediated effects. Created with https://www.figdraw.com/#/.

In conclusion, immune activation constitutes a pivotal initiating event in the pathophysiology of amniotic fluid embolism. This process encompasses anaphylactoid and anaphylactic responses, complement system activation, and an extensive release of proinflammatory mediators. These immunological perturbations compromise vascular integrity, precipitate widespread endothelial injury, and lay the groundwork for subsequent organ dysfunction. The downstream impact of this dysregulated immune response contributes substantially to cardiopulmonary collapse, which is discussed in the ensuing section.

As previously mentioned, amniotic fluid contains both vasoactive and procoagulant substances, including platelet-activating factor, cytokines, bradykinin, leukotrienes, and arachidonic acid. Leukotrienes can interact with inflammatory mediators such as endothelin (ET) and interleukins released by the activated maternal immune system, ultimately contributing to bronchoconstriction and vasoconstriction [24, 25, 26]. A hypothesis suggests that when amniotic fluid enters the systemic vasculature, the concentrations of endothelin in maternal plasma rise [13]. Endothelin is known to induce constriction of the bronchi and coronary arteries, potentially leading to respiratory and cardiovascular failure [27, 28].

When bronchial and pulmonary vasoconstriction occurs, pulmonary pressure rises, prompting compensatory dilation of the right atrium and ventricle [1, 29]. This leads to hypoxia and eventual right heart failure. The resulting right ventricular enlargement causes displacement of the interventricular septum, impairing left ventricular function. This, combined with myocardial ischemia from hypoxia or coronary artery spasm, further compromises cardiac output [1, 29]. The disruption of normal pulmonary gas exchange can result in respiratory failure, hypoxemia, and the development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Increased pulmonary artery pressure, reduced cardiac output, and vascular leakage induced by inflammatory mediators collectively lead to a diminished effective circulating blood volume, potentially resulting in circulatory shock [30]. Haemodynamic instability in the mother may also trigger arrhythmias, including ventricular fibrillation, asystole, and pulseless electrical activity, which are associated with significant morbidity and mortality. The progression of cardiopulmonary failure is illustrated in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The cardiopulmonary failure process. The figure illustrates the progression from pulmonary vasoconstriction and bronchoconstriction to right heart strain, left ventricular dysfunction, impaired gas exchange, and systemic complications such as disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC) and acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Created with https://www.figdraw.com/#/.

Autopsy reports of AFE frequently show that the heart, lungs, and uterus are the most severely affected organs, with pulmonary edema and alveolar hemorrhage being the predominant findings. In numerous autopsy findings of AFE, the heart, uterus and lungs are the most severely affected, and pulmonary edema and alveolar hemorrhage account for the majority of cases [1, 31]. The heart and lungs, as the organs fundamental to the body’s gas exchange and circulatory functions, are of undeniable significance. In addition to the direct damage caused by inflammatory mediators, the interplay among various pathological factors often leads to coagulation abnormalities and DIC, further destabilizing maternal hemodynamics and initiating a cascade of adverse events. Autopsies also reveal numerous scattered hemorrhagic lesions in vital organs such as the lungs and intestines, which will be discussed in the following section. The combined effects of components in the amniotic fluid and endogenous inflammatory mediators ultimately result in complications associated with significant morbidity and mortality, including cardiopulmonary failure, shock, ARDS, and DIC. In cases of cardiopulmonary collapse, prompt and effective resuscitation and circulatory support are essential to improve maternal outcomes [32].

Cardiopulmonary compromise in AFE arises as a direct consequence of immune-mediated vascular dysfunction, leading to bronchoconstriction, pulmonary hypertension, and cardiac decompensation. The resultant hypoxaemia, right heart strain, and diminished cardiac output further exacerbate systemic hypoperfusion. This haemodynamic instability not only imperils maternal survival but also facilitates a procoagulant state through endothelial disruption and circulatory stasis. The implications of this state for coagulation homeostasis and the onset of disseminated intravascular coagulation are explored in the following section.

DIC is a severe thrombo-haemorrhagic disorder associated with significant morbidity and mortality and remains one of the leading causes of maternal death globally [33, 34, 35]. DIC is usually secondary to maternal/fetal diseases such as placental abruption or amniotic fluid embolism [36]. DIC is a prominent clinical feature of AFE and, in some atypical cases, may present as the sole manifestation. It is also frequently the primary cause of death in affected patients. Statistics indicate that over 83% of individuals diagnosed with AFE develop DIC [13].

Amniotic fluid contains various vasoactive and procoagulant substances, including platelet-activating factor, cytokines, bradykinin, thromboxane, tissue factor (TF), and tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI) [37, 38]. These components can stimulate the maternal immune system, leading to the release of numerous inflammatory mediators that may contribute to tissue injury. Under normal physiological conditions, a balance exists between TF and its inhibitor, TFPI, maintaining coagulation homeostasis [39]. However, this balance can be disrupted by factors such as tissue damage and the excessive release of tissue factor, resulting in the activation of the extrinsic coagulation pathway [40]. Simultaneously, damage to vascular endothelial cells and exposure of basement membrane collagen can initiate the intrinsic coagulation cascade [41]. In addition, the release of adenosine diphosphate (ADP) and thromboxane A2 promotes platelet activation and aggregation, further contributing to microthrombus formation [42]. Moreover, proinflammatory cytokines such as IL-1 and TNF-

For decades, researchers have sought to unravel the mechanisms driving DIC in the context of AFE. Although some advances have been made, the inherent complexity of AFE, difficulties in data collection, and the challenges of real-time monitoring of the numerous molecular players involved have left the precise progression of DIC largely undefined. Once DIC develops, it is extremely difficult to reverse. Therefore, gaining a comprehensive understanding of its underlying mechanisms, implementing preventive strategies prior to its onset, and initiating early intervention during the initial stages are crucial steps in effectively managing disease progression and improving patient outcomes.

Disseminated intravascular coagulation in the context of AFE reflects the culmination of preceding immunological and haemodynamic insults. The concomitant activation of coagulation and fibrinolytic pathways results in consumptive coagulopathy, microvascular thrombosis, and uncontrolled haemorrhage. This imbalance often proves refractory to intervention and significantly contributes to multi-organ failure. Collectively, immune dysregulation, cardiopulmonary collapse, and DIC form an interdependent triad that underscores the catastrophic clinical trajectory characteristic of AFE.

AFE is a highly complex condition involving severe and multifaceted pathophysiological processes, which has hindered the development of specific diagnostic and therapeutic approaches. At present, treatment remains purely supportive, with the main clinical challenges stemming from the syndrome’s sudden onset and rapid progression [7]. There is broad consensus that initial management of AFE should prioritize airway stabilization, respiratory support, and circulatory assistance (see Appendix Table 1).

In cases of maternal cardiac arrest, prompt and effective cardiopulmonary resuscitation is imperative [8]. Moreover, special care must be taken to avoid hyperventilation. If circulation is not restored within 4 minutes of cardiac arrest or if fetal status remains compromised despite maternal stabilization—an emergency cesarean section should be performed within 5 minutes [8, 32]. For pregnancies beyond 23 weeks of gestation, prompt delivery by cesarean section is both necessary and potentially life-saving [1]. However, for fetuses under 20 weeks of gestation, uterine evacuation may not significantly improve maternal clinical symptoms [1]. It is therefore essential that maternal resuscitative efforts continue uninterrupted throughout the procedure. Additionally, the study recommends leftward displacement of the gravid uterus to reduce aortocaval compression and enhance maternal circulation [46].

Patients with AFE often require varying levels of vasoactive drug support, and the establishment of central venous access is essential for medication administration and hemodynamic monitoring [32]. Norepinephrine serves as the vasopressor of choice [47]. Positive inotropic agents such as dobutamine and milrinone are particularly effective in reducing right ventricular afterload and alleviating pulmonary vasoconstriction [32]. However, it is important to recognize that vasopressor use can increase pulmonary vascular resistance, which may precipitate or worsen right ventricular failure. As such, continuous monitoring, appropriate ventilator adjustments, and prevention of fluid overload are critical components of care. In cases requiring prolonged cardiopulmonary resuscitation or when right heart failure does not respond to conventional therapy, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) may be considered [48]. In a 13-year retrospective study conducted at two high-volume ECMO centres, the survival rate among ten parturient women with AFE treated with venoarterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (VA-ECMO) reached 70%, despite severe haemodynamic compromise, including cardiac arrest in 70% of cases and a median left ventricular ejection fraction of 14%. VA-ECMO is well established for providing sustained cardiopulmonary support in cases of profound circulatory and respiratory failure, and these findings underscore its potential utility in managing AFE, a condition associated with significant morbidity and mortality, notwithstanding concerns regarding coagulopathy and bleeding risk [47].

Fluid resuscitation plays a vital role in managing refractory hypotension in patients with AFE [40]. Initial treatment involves the rapid administration of isotonic crystalloid and colloid solutions, and when necessary, transfusion of packed red blood cells to restore adequate oxygen delivery [40]. In the early phase of DIC, it is crucial to administer tranexamic acid in a timely manner to treat hyperfibrinolysis [49, 50, 51]. Based on the severity and volume of blood loss, transfusions of red blood cell concentrates and fresh frozen plasma (FFP) may be required to support hemostasis and maintain hemodynamic stability [50, 52]. In cases where extensive coagulation factor replacement fails to control bleeding, the use of recombinant factor VIIa may be considered to improve clot formation and achieve hemostasis [53].

In addition to the established treatment strategies, several emerging therapies show potential as novel approaches for managing AFE. Hemofiltration and plasma exchange transfusion have demonstrated the ability to reduce elevated levels of inflammatory mediators in the bloodstream effectively [54, 55]. A case report from California documented a woman with placenta previa who received a massive injection of methylprednisolone during bypass surgery after cardiac arrest to keep her breathing and circulation alive, even though she later had severe sequelae. Although high-dose glucocorticoid pulse therapy is known for its anti-inflammatory benefits in other critical conditions, its efficacy in treating AFE remains uncertain and requires further investigation [56]. C1 esterase inhibitor (C1INH) concentrate shows promise as a therapeutic option for amniotic fluid embolism (AFE), as C1INH activity levels are markedly reduced in AFE patients (30.0%

AFE affects multiple organ systems, resulting in a wide range of complex and varied clinical manifestations. The classic triad typically includes respiratory distress, hypotension, and DIC [8]. However, atypical presentations are not uncommon; some patients may exhibit only hypotension or cardiopulmonary dysfunction, while in rare cases, DIC may be the sole clinical feature [8]. The disease etiology of the phenotype where DIC is the sole symptom might be associated with uterine atony [1]. As a result, not all individuals with AFE experience the full spectrum of pathophysiological changes described previously. Diagnosis and management must therefore be decided according to the immediate clinical manifestations, as well as biochemical and imaging examinations.

Based on extensive research, Uszyński and Uszyński [60] proposed that the typical clinical course of AFE progresses through three distinct stages. The first stage, occurring within minutes, is characterized by sudden cardiopulmonary collapse, shock, and, in some cases, immediate maternal death [60]. If resuscitation is successful, the second stage often follows, marked by the onset of coagulopathy, typically presenting as widespread bleeding, most notably from the uterus [60]. The third stage commonly involves renal failure or even progression to multiple organ failure. Although Uszyński’s model is based on observational data, we believe that the pathophysiological processes in AFE do not necessarily follow a strict chronological sequence. Some researchers suggest that depletion of coagulation factors may begin concurrently with cardiopulmonary failure or may emerge more gradually [60]. Therefore, once amniotic fluid enters the maternal circulation, immune activation, cardiopulmonary dysfunction, and DIC may occur simultaneously or with partial temporal overlap. This variability and complexity underscore why AFE remains such a challenging condition to diagnose and treat. Hence, continued research is essential to better understand its mechanisms and improve clinical outcomes.

Activation of the maternal immune system in amniotic fluid embolism (AFE) likely involves a combination of immune cell activation, anaphylaxis, and complement system activation. A key mechanism is believed to be the interaction between DAMPs and pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), which initiates the activation of immune cells such as macrophages and dendritic cells [61]. Once macrophages are activated, they can secrete substantial amounts of TNF-

The clinical symptoms and laboratory abnormalities observed in patients with AFE are the result of a complex interplay of multiple pathophysiological mechanisms. Therefore, a thorough and integrated evaluation is crucial for accurate assessment. Activation of the maternal immune system leads to the release of inflammatory mediators, which can induce pulmonary hypertension, potentially progressing to heart failure and resulting in hypotension. These same inflammatory mediators can also activate the coagulation cascade, contributing to the development of DIC. Once DIC sets in, it disrupts microcirculation and further destabilizes maternal hemodynamics. As AFE progresses, a range of complications may emerge, including hypoxia, pulmonary edema, ARDS, renal dysfunction, and neurological impairment. Thus, given the complexity of these interactions, diagnosis and treatment should not rely on any single pathophysiological process or isolated clinical finding. Instead, a holistic evaluation that considers maternal symptoms, laboratory data, and fetal status is essential for accurate diagnosis and effective management.

Despite our growing understanding of potential mechanisms of AFE, significant limitations persist in pathophysiological research [63]. Although the widely accepted trigger is the entry of amniotic fluid components into the maternal circulation, the specific constituents responsible for initiating the cascade associated with significant morbidity and mortality, as well as the precise conditions under which this occurs, remain poorly defined. Thus, continued investigation is vital to clarify these unresolved questions and improve outcomes for affected patients.

Emerging evidence highlights the relevance of broader maternal health factors in the context of AFE. Nutritional imbalances, including deficiencies or altered metabolism of inositols and alpha-lipoic acid, have been linked to adverse outcomes in women’s reproductive health and may potentially influence the risk or severity of AFE, though direct evidence remains limited and warrants further investigation [64]. In parallel, the increasing use of assisted reproductive technologies (ART), particularly frozen embryo transfer (FET), has introduced new clinical challenges [65]. FET is associated with higher rates of macrosomia and large-for-gestational-age newborns, while long-term developmental outcomes remain an active area of research [66]. Moreover, the psychological burden on mothers experiencing AFE, especially those who conceived via in vitro fertilisation (IVF), should not be underestimated. For these high-risk individuals, comprehensive care—including nutritional optimisation, psychological support, and long-term follow-up—is essential for improving both maternal and neonatal outcomes [67].

AFE is characterized by the sudden dysfunction of multiple organ systems, including immune system activation, cardiopulmonary collapse, and coagulation abnormalities such as DIC, all of which have been discussed in detail. However, the precise temporal and spatial relationships between these processes remain unclear. Most current studies on AFE are retrospective in nature, relying on the analysis of medical records, which limits their accuracy compared to controlled experimental research. The complexity of pathophysiology of AFE, combined with its rapid clinical progression, contributes to the current lack of targeted treatment strategies [68]. In this context, we have aimed to provide a comprehensive overview of the key factors involved in pathogenesis of AFE, integrating existing knowledge with previously discussed mechanisms. Overall, by deepening the understanding of these interconnected processes, our goal is to facilitate earlier clinical recognition, enhance patient outcomes, and ultimately reduce the maternal mortality associated with this devastating condition.

AFE is a disease characterized by a rapid onset, a perilous presentation, a multiplicity of symptoms, and a high degree of complexity. The underlying mechanisms are multifaceted and not yet fully elucidated, and to date, there are no universally accepted diagnostic criteria. In this review, we provide a comprehensive and systematic summary of the currently recognized pathophysiological pathways associated with AFE. These include immune system activation, cardiopulmonary dysfunction, and coagulation abnormalities. In addition to consolidating existing knowledge, we also present informed hypotheses aimed at further refining the understanding of AFE’s intricate pathogenesis.

Thus, considering the rapid deterioration often observed in patients with AFE, prompt and coordinated medical intervention is critical. There is growing support within the medical community for a multidisciplinary approach to managing AFE, involving obstetricians, anesthesiologists, intensivists, and hematologists. Such collaborative care can facilitate early recognition, timely intervention, and optimized supportive management factors that are essential to improving maternal outcomes and reducing mortality. This paper aims to contribute valuable insights that may aid in the development of standardized clinical diagnostic criteria for AFE. Furthermore, it underscores the importance of enhancing both preventive strategies and therapeutic protocols through continued research and clinical collaboration.

Looking ahead, we advocate for several priority areas of research to address the current gaps in AFE understanding and care. These include the development and validation of specific diagnostic biomarkers to enable earlier and more accurate detection, the establishment of prospective multi-centre registries to systematically capture clinical data and outcomes, and the advancement of mechanistic studies using in vitro and in vivo models to dissect the complex immunological and haemodynamic interactions underpinning AFE. By shedding light on the current understanding and the unresolved challenges of AFE, we hope to support clinicians and researchers in advancing effective management practices for this devastating condition.

GH and XZ conceived the review topic. LW and LZ collected the literature and authored the paper. JW drew the figures. YB curated the data. LC provided conceptual guidance. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

We affirm that the content of this manuscript was entirely conceived, designed, and written by the authors. During the drafting stage, we utilized OpenAI solely for minor language refinement purposes, such as improving grammar and enhancing readability. No sections of the manuscript were generated or authored by AI tools.

See Table 1.

| Category | Intervention | Purpose | Level of Evidence | Comments |

| Initial Resuscitation | Airway stabilization, respiratory and circulatory support | Ensure oxygenation and perfusion | Expert consensus, clinical guidelines [6, 7] | First-line, time-sensitive interventions |

| Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) | Restore circulation during cardiac arrest | Strong clinical consensus [7] | Cesarean within 5 minutes if no return of circulation | |

| Emergency Cesarean section | Improve maternal and fetal outcomes | Moderate evidence [1, 31] | Most effective | |

| Left uterine displacement | Reduce aortocaval compression | Expert consensus [45] | Simple maneuver to support maternal circulation | |

| Hemodynamic Support | Norepinephrine | Vasopressor to stabilize blood pressure | Clinical practice [46] | First-line agent |

| Dobutamine, Milrinone | Inotropes support RV function | Case-based support [31] | Use with caution due to pulmonary vasoconstriction risk | |

| Central venous access | Drug delivery and monitoring | Standard ICU practice [31] | Enables aggressive hemodynamic management | |

| ECMO | Circulatory/respiratory support in refractory cases | Case series [47] | Reported survival rate | |

| Coagulation Management | Isotonic crystalloid and colloid solutions | Initial fluid resuscitation | Clinical standard [39] | First step in volume resuscitation |

| Blood product transfusion (RBC, FFP) | Correct hypovolemia and coagulopathy | Clinical guidelines [49, 51] | Dosed based on blood loss and coagulation status | |

| Tranexamic acid | Treat hyperfibrinolysis in early DIC | RCT-based evidence [48, 49, 50] | Early administration critical | |

| Recombinant factor VIlla | Achieve hemostasis in uncontrolled bleeding | Limited clinical data [52] | Last resort when conventional measures fail | |

| Emerging/Experimental | Hemofiltration, plasma exchange | Remove inflammatory mediators | Preliminary evidence [53, 54] | Experimental; not routine |

| High-dose glucocorticoids | Anti-inflammatory effect | Unclear efficacy [55] | Evidence from other critical illness, not AFE-specific | |

| C1 inhibitor concentrate | Modulate complement activation | Case reports [56] | Mechanism-based investigational |

ECMO, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation; RBC, red blood cell; FFP, fresh frozen plasma; RV, right ventricle; DlC, disseminated intravascular coagulation; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.