1 Clinic for Gynecology and Obstetrics Narodni Front, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia

2 Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia

3 Division of Obstetrics and Feto-Maternal Medicine, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Medical University of Vienna, 1090 Vienna, Austria

4 Faculty of Dental Medicine, University of Belgrade, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

This review aimed to implement a search strategy focused on vaginal candida infections in pregnant women and to analyze specific vulvovaginal symptom questionnaires (VSQs) for Candida infections.

A literature review was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Scopus databases were searched for studies published between 1997 and 2023. The search strategy included keywords related to vaginal candidiasis, pregnancy, risk factors, symptoms, and self-assessment VSQs. The studies were assessed for quality using Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Tools, focusing on validity, reliability, and appropriate statistical methods.

A total of 36 papers with vaginal candidiasis reported during pregnancy were included (1997–2023), along with 14 papers reporting the use of VSQs. The literature was found to lack sufficient data, with a wide variation in population size and data across studies. Sample sizes ranged from as few as 80 patients to as many as 13,863 patients in other studies. Notably, a significant age range was observed among the participants, spanning from 10 to 64 years. Additionally, symptoms and signs were not investigated in 17 studies, while risk factors were not discussed in 20 studies. A total of 14 studies were identified; however, only one was presented with a fully developed VSQ, which had been validated and was available in multiple languages. Meanwhile, none of the studies focused on pregnant women and the role of VSQs.

Incorporating self-assessment VSQs into clinical practice would improve everyday practice and increase awareness among pregnant women regarding vulvovaginal Candida infections, improve the identification and management of these infections, leading to earlier detection, more timely treatment, and improved health outcomes for newborns.

Keywords

- Candida

- yeasts

- vaginal infection

- pregnancy

- diagnosis

- survey

Candida species, the predominant fungal yeast pathogens, are a common cause of opportunistic infections, especially in immune-compromised individuals or those at some other risk, such as pregnancy. Meanwhile, vulvovaginal candidiasis (VVC) represents one of the most common conditions, affecting more than 30% of pregnant women. By definition, VVC represents an infection of the oestrianized vagina and vestibule that can spread outside the small labia, large labia, and perianal region, and can affect the quality of life of patients, but also has the potential to affect newborns [1]. Studies have identified risk factors for developing Candida infections, as well as clusters of signs and symptoms associated with selected conditions, as we previously reported [2]. While conventional approaches, such as clinical diagnosis, laboratory testing, and patient-taking history, remain foundational, self-assessment questionnaires offer a faster, non-invasive, and efficient method for identifying symptoms and evaluating risk factors. Hence, integrating existing research with the development and application of the self-assessment tool could provide valuable resources for clinicians and enhance early detection of patients at risk for vaginal Candida infections based on patient-reported data. However, such data are lacking in the current literature. Presently, only the vulvovaginal symptom questionnaire (VSQ) exists [3], which was developed in 2013 in the USA, and is based on the symptoms of postmenopausal women. The VSQ represents a questionnaire that comprises 21 self-assessment questions, which are not based only on the diagnosis, but on the psychometric parameters, such as emotions, life, and sexual impact, to provide a more comprehensive evaluation. The questions included in the VSQ address the following symptoms: vulvar itching, burning or stinging, pain, irritation, dryness, and discharge or odour from the vulva and/or vagina. Currently, the questionnaire has been translated and validated in only a few languages, including Brazilian-Portuguese, Japanese, Persian, Turkish, and Chinese. Additionally, we found a few specific Candida questionnaires (e.g., Candida screening questionnaire, Candida questionnaire & score sheet, and Test Yourself for Yeast Overgrowth); however, these are more intended for commercial purposes with a clear score sheet at the end of the survey to test yourself. Furthermore, none have been translated or validated in the general population or among pregnant women. Therefore, the sensitivity and specificity of these questionnaires are not available.

The study aimed to perform a search strategy focused on vaginal candidiasis in the pregnant population. The second aim of this review was to provide a comprehensive analysis of self-reporting VSQ for symptoms, signs, and risk factors in patients with vaginal infections, and to propose a potential role of novel self-assessment VSQ in pregnancy.

This literature review was conducted according to the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [4]. The literature search was conducted in 2023 using the MEDLINE, Web of Science, and Scopus databases. Preference was given to sources published within the past 20 years, except for the questionnaire review, which had no date restrictions due to the limited availability of data. The search strategy consisted of keywords combination such as controlled vocabulary (Medical Subject Headings, MeSH) and accessible text terms: (1) For literature review: (vaginal or vaginitis or vulvovaginitis or vulvovaginal) AND (Candida or candidiasis) AND (Pregnancy or pregnant women) AND (risk factors) AND (symptoms or signs); (2) for the questionnaire review: (questionnaire) AND (Candida or candidiasis) AND (vaginal infections or vaginitis or vulvovaginitis or vulvovaginal).

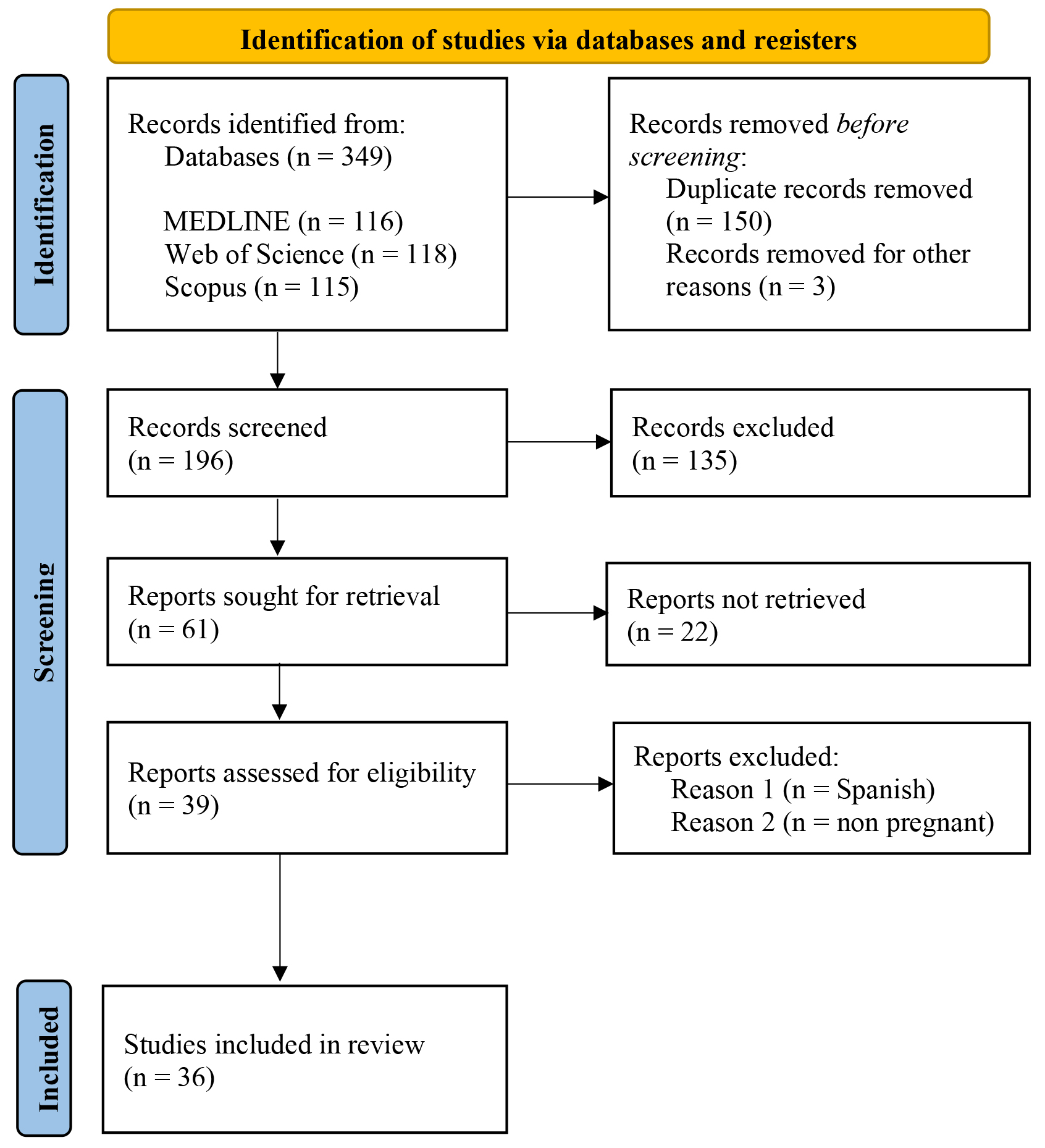

The inclusion criteria for the literature review were as follows: (1) pregnant women, (2) confirmed diagnosis of vulvovaginal candidiasis, (3) clinical signs and symptoms of vaginal infection, (4) English as preferred language, and (5) no age restriction. Some studies included participants as young as 10 years and as old as 64, indicating the involvement of individuals outside the typical reproductive age range, although such cases were less common. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) studies on animals, (2) abstracts, (3) languages other than English, and (4) past treatment for vaginal candidiasis (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flowchart. Literature selection for the analysis of predisposing factors, signs, symptoms, and Candida spp. vaginal infection in pregnancy.

The outcome variable evaluated in the included studies was Candida-positive vulvovaginitis in pregnant women. We extracted the following data: continent, country, number of patients with vulvovaginal infection with Candida, age, causative agents, signs and symptoms, and risk factors. The data extracted from the selected studies were presented in a tabular format, and compared narratively. Pooling the studies statistically was not possible because of the heterogeneity in study designs, patient characteristics, and outcomes. The purpose of this systematic review was to identify research gaps within a specific area and provide a comprehensive summary of the evidence related to a research problem.

Regarding the questionnaire review, we initially included 23 questionnaires. Subsequently, four questionnaires were initially excluded due to being hosted on “unofficial” websites and not part of any published study. Furthermore, the data were neither validated nor examined in any population. These types of questionnaires are often easily accessible to pregnant women, which may lead to misleading predictions regarding the suspicion of VVC. The remaining 19 studies were screened, and two were excluded because healthcare professionals completed the questionnaires. One study was removed due to the inclusion of male participants; a further study examined only vulvodynia on the pain scale, while another evaluated the effectiveness of a pharmaceutical product. The inclusion criteria for the questionnaire review were as follows: (1) questionnaire, (2) sexually active women, (3) assessment of vaginal infection, and (4) English as the preferred language. The exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) questionnaire completed by physicians, (2) abstracts, (3) languages other than English, and (4) men.

Study designs of interest included prospective, cross-sectional, and/or retrospective studies. The included original articles were cohort, cross-sectional, or retrospective studies categorized by study design.

The selection of studies was conducted by two authors, VG and BS, who first reviewed the titles and abstracts. The studies that met the inclusion criteria were then assessed by BM and ND, under the supervision of a third author, VAA. The extracted data included the author, year of publication, country, sample size, frequency of infection, risk factors, signs and symptoms, and the distribution of Candida species. For the questionnaire review, the study search was conducted by AJ and LP, while VAA performed the selection based on the criteria. Another third author, BM, performed data extraction from the studies, which included the author, year of publication, type of questionnaire, language or country of origin, number of questions, and tested parameters. Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical appraisal tools were used to assess the quality of the eligible studies. These tools consist of eight domains related to clear inclusion criteria, detailed setting description, valid/reliable exposure, objective/standard measurement criteria, confounding factor identification, strategies for dealing with confounding factors, valid, reliable outcome measurement, and appropriate statistical analysis.

The JBI Critical appraisal tools were used to assess the risk of bias for cross-sectional studies. Critical appraisal of the included studies was conducted independently by two authors (BM and VAA). Each study was evaluated based on the following criteria: Clear inclusion criteria, setting description, valid/reliable exposure, objective/standard measurement criteria, confounding factor: Identification and dealing strategies, valid, reliable outcome measurement, and appropriate statistical analysis. Disagreements during the assessment were discussed and resolved by a third author (VG). In the quality assessment of the included studies, 13 had the maximum number of positive responses according to the quality assessment score. Two studies had 7 out of 8 positive criteria, eleven had 6 out of 8 positive criteria, and the remaining 10 studies had 5 out of 8 positive criteria from the quality assessment. The common shortcoming in studies that did not achieve the maximum number of points was the lack of analysis of confounding factors, specifically the failure to examine risk factors and identify risk groups for VVC infection in pregnant women. One study lacked strategies for dealing with confounding factors, and one had unclear data for these criteria. Eleven studies did not have unclear evidence of confounding factors: Identification and dealing strategies. Moreover, the authors excluded potentially confounding groups and did not perform adequate statistical analysis in nine studies. Therefore, the overall quality of the evidence for this study can be considered “good”.

PRISMA presented data from the 36 studies identified in this review, involving a total of 26,880 women aged 10 to 64 years, of whom 24,966 were pregnant. The majority of studies were from Asia (n = 16), while the fewest were from Europe (n = 5), America (n = 5), and Australia (n = 1), as presented in Table 1 (Ref. [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40]).

| Authors, year [Reference] | Country (pregnant/sample size) | Age range (mean age) (years) | Main signs and symptoms | Key predisposing factors in pregnancy |

| Africa (n = 9) | ||||

| Akerele J et al., 2002 [5] | Nigeria (500/500) | 15–35 (28) | Plaques | ND |

| Abdelaziz ZA et al., 2014 [6] | Sudan (200/200) | 17–47 (ND) | ND | ND |

| Asmah RH et al., 2017 [7] | Ghana (99/99) | 18–30+ (ND) | ND | Immunocompromising state, partner faithfulness |

| Sangaré I et al., 2018 [8] | Burkina Faso (229/229) | 15–49 (26) | Low abdominal pain, burning sensation, malodor, discharge | ND |

| Mushi MF et al., 2019 [9] | Tanzania (300/300) | ND (27 | Pruritus, discharge, burning sensation | Douching, sexually transmitted infections, antibiotic use, socioeconomic status |

| Tsega A and Mekonnen F., 2019 [10] | Ethiopia (384/384) | 18–40 (ND) | ND | HIV, frequent use of contraceptives, prolonged antibiotic use, number of gravidities, gestational period, age |

| Waikhom SD et al., 2020 [11] | Ghana (176/176) | 15–42 (29) | Burning sensation, discharge | ND |

| Sule-Odu AO et al., 2020 [12] | Nigeria (400/400) | 17–42 (29.4) | Discharge | ND |

| Shawaky SM et al., 2022 [13] | Egypt (310/516) | ND (28.71 | Discharge, pruritus, dysuria, dyspareunia | DM, frequent sexual intercourse |

| North and South America (n = 5) | ||||

| Cotch MF et al., 1998 [14] | USA (13,863/13,863) | ND | Pruritus | Ethnicity, marriage, contraceptives |

| Caramalac DA et al., 2007 [15] | Brazil (100/100) | ND | ND | ND |

| Dias LB et al., 2011 [16] | Brazil (90/404) | 16–50 (ND) | Discharge | ND |

| Mucci MJ et al., 2016 [17] | Argentina (210/210) | 10–42 (27.9) | Discharge, pruritus, burning sensation, dysuria, dyspareunia | Gestational week |

| Akpaka PE et al., 2022 [18] | Republic of Trinidad and Tobago (492/492) | 18–52 (ND) | ND | Gestational week, gravity, age, ethnicity, locality, educational level, employed, monthly income, weight (pre-pregnancy), previous infection, treatment of infection, current illness/disease, antibiotics treatment, type of contraceptives |

| Asia (n = 16) | ||||

| Abu-Elteen KH et al., 1997 [19] | Jordan (41/140) | 18–50 (28) | Discharge, pruritus, dysuria, dyspareunia | ND |

| Wenjin Q and Yifu S, 2006 [20] | China (628/628) | 17–45 (ND) | ND | ND |

| Guzel AB et al., 2011 [21] | Turkey (372/372) | 17–45 (29.3 | Pruritus, burning, inflammation, irritation, dysuria, dyspareunia, discharge | Gestational week, gravidae, HbA1c, sexual intercourse during pregnancy, the use of a daily pad, poorer genital hygiene, more frequent use of public toilets |

| Kalkanci A et al., 2012 [22] | Turkey (207/207) | 18–49 (ND) | Pruritus, burning sensation, discharge, dyspareunia, dysuria | ND |

| Faidah H, 2013 [23] | Saudi Arabia (161/491) | 20–45 (33) | ND | Multiple pregnancies |

| Lakshmi SJ et al., 2015 [24] | India (14/100) | 11–50 (ND) | Discharge | ND |

| Masri SN et al., 2015 [25] | Malaysia (1163/1163) | 18–30+ (ND) | ND | Gestational week, DM |

| Yang L et al., 2016 [26] | China (657/657) | 21–45 (29.3 | ND | Age |

| Zhai Y et al., 2018 [27] | China (993/993) | ND | ND | ND |

| Khan M et al., 2018 [28] | Pakistan (450/450) | 17–44 (27) | Pruritus, discharge, pain, inflammation, dysuria dyspareunia | Oral contraceptive pills, DM, tuberculosis |

| Kiasat N et al., 2019 [29] | Iran (20/493) | 15–64 (ND) | Pruritus, burning, discharge, malodor, inflammation | ND |

| Ghaddar N et al., 2019 [30] | Lebanon (221/221) | 20–40 (ND) | Discharge, pruritus, malodor | Age, level of education |

| Ghaddar N et al., 2020 [31] | Lebanon (258/258) | 20–41+ (34) | ND | ND |

| Abu-Lubad M et al., 2021 [32] | Jordan (200/200) | 20–45 (ND) | ND | ND |

| Hizkiyahu R et al., 2022 [33] | Israel (102/204) | ND (28.78 | ND | ND |

| Only positive | ||||

| Yadav L and Yadav R, 2023 [34] | Nepal (90/150) | 16–45 (30.33) | Burning sensation, pruritus, malodor, discharge, dysuria | ND |

| Australia (n = 1) | ||||

| Payne MS et al., 2016 [35] | Australia (191/191) | 18–43 (30) | ND | ND |

| Europe (n = 5) | ||||

| Arena B and Daccò MD, 2021 [36] | Italy (245/245) | ND (32) | ND | Composition of intestinal microbiota |

| Holzer I et al., 2017 [37] | Austria (1066/1066) | ND (30.2 | ND | ND |

| Babic M and Hukic M, 2010 [38] | Bosnia and Herzegovina (203/447) | 20–38 (ND) | Inflammation | ND |

| Zisova LG et al., 2016 [39] | Bulgaria (80/80) | 18–40 (8.2 | Discharge, pruritus | Previous episodes of VVC |

| Nowakowska D et al., 2004 [40] | Poland (251/251) | ND (29.13) | ND | DM |

ND, not detected; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; DM, diabetes mellitus; VVC, vulvovaginal candidiasis; HbA1c, Hemoglobin A1C/glycated hemoglobin.

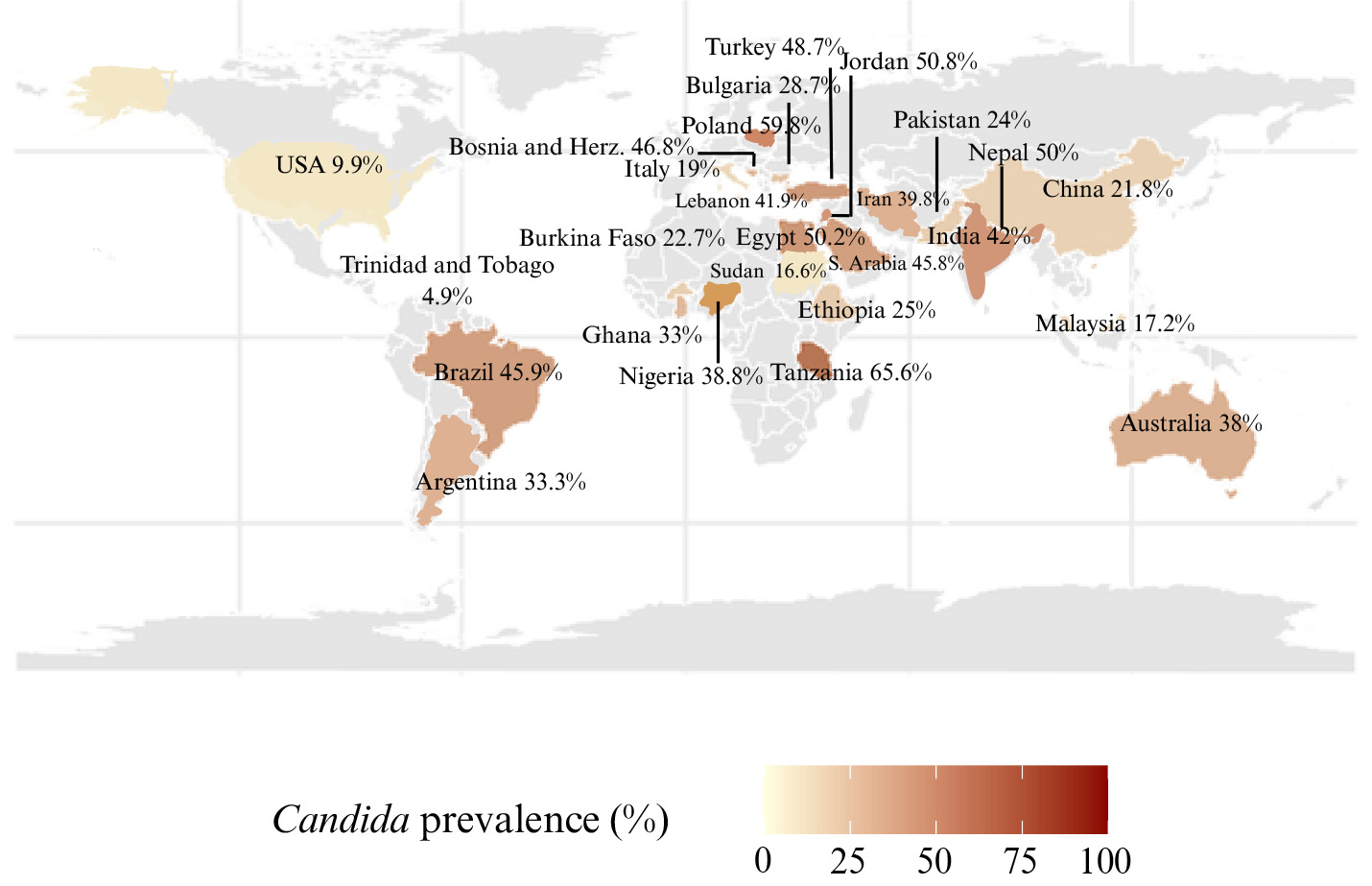

The incidence of Candida species vaginal infection in pregnancy across available literature ranged from a low of 9.9% in the USA [14] and 65.6% in Tanzania [9]. Overall, Africa, Asia, and Europe were found to share similarly moderate prevalence levels, while the Americas exhibited a wider spread toward lower incidence rates.

In Africa, positive Candida rates ranged from 16.6% [6] to 65.6% [9], while several studies reported moderate rates, such as 50.2% (Egypt, [13]). Asia displayed some of the highest Candida positive rates, ranging from 17.2% in Malaysia [25] to 68.2% in Jordan [19], highlighting a significant burden in specific regions. A single study from Australia reported a positivity rate of 38% [35], falling within the global moderate range and aligning with findings in Africa and Asia. The positive rates in North and South America displayed a wider distribution, with a comparatively low maximum reported incidence of 47% in Brazil [15]. European studies reported positivity rates ranging from 19% in Italy [36] to 59.8% in Poland [40], with moderate to high rates in Bosnia and Herzegovina (46.8%) [38] and Poland (59.8%) [40], suggesting a considerable prevalence of Candida infections in certain regions of Europe (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Global epidemiological data of the Candida and vulvovaginal candidiasis prevalence in pregnancy in 2023.

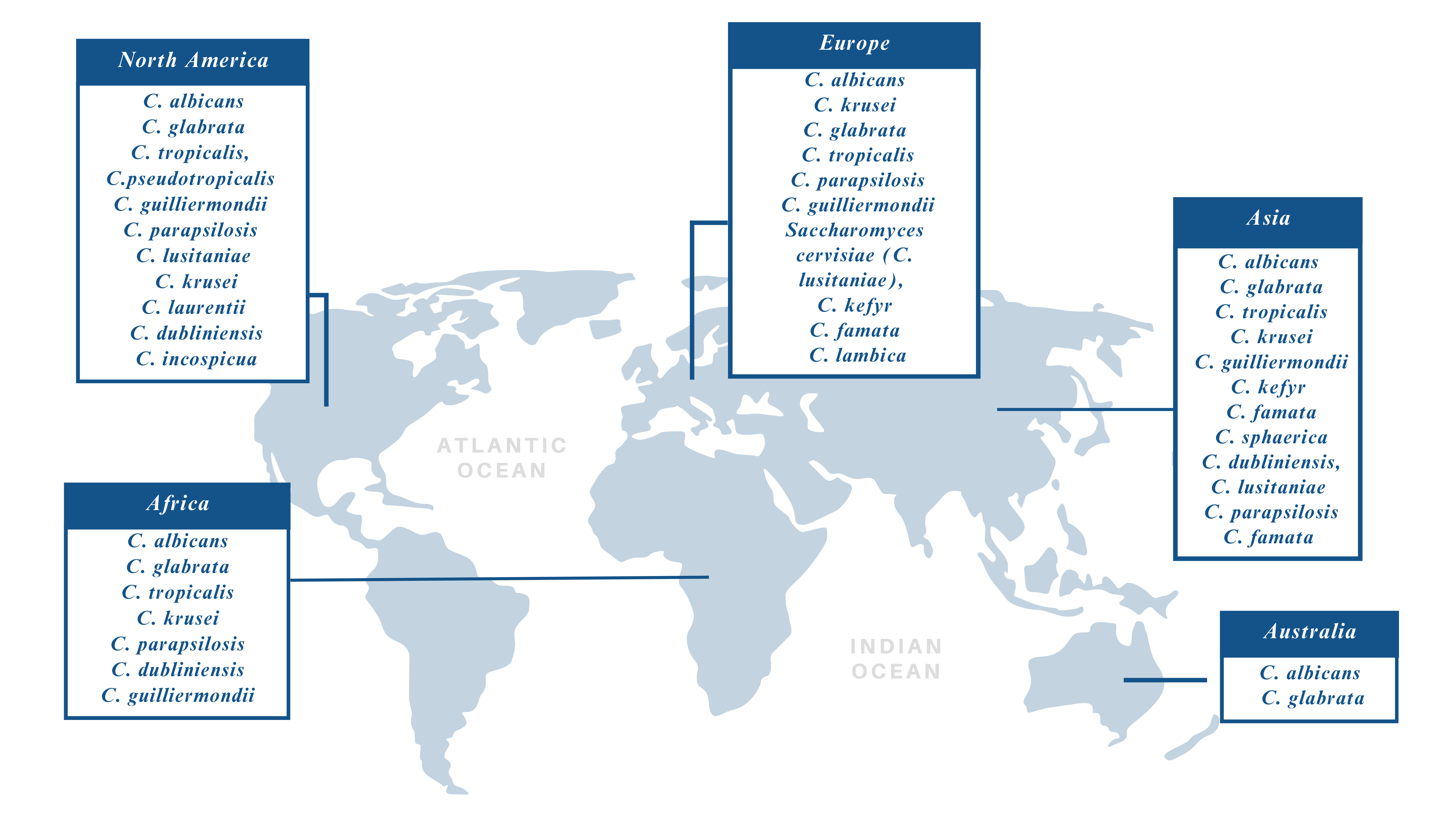

Among all the studies reviewed, C. albicans was the most frequently reported species, appearing in 34 studies [5, 6, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 38, 39, 40]. Notably, two studies acknowledged the limitation of not differentiating between the various Candida species [7, 37]. This underscores the global prominence of C. albicans in Candida infections across the reported continents. Meanwhile, non-albicans species also played a significant role, as C. glabrata, C. krusei, and C. tropicalis were frequently reported as non-albicans species, with C. glabrata notably common in Asia [19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33]. C. glabrata was the next most identified species (29 studies, [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 35, 36, 38, 40]), followed by C. krusei in 26 studies [8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 36, 38, 39, 40] and C. tropicalis in 21 studies [8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 32, 38, 40]. Other species, such as C. parapsilosis (13 studies, [9, 11, 15, 16, 17, 21, 22, 26, 27, 32, 33, 38, 40]) and C. guilliermondii (6 studies, [13, 15, 19, 21, 22, 38]), were less frequently reported. Comparatively, rare species, such as C. lusitaniae [15, 21, 22, 27, 40], C. kefyr [21, 22, 40], and C. famata [21, 22, 25, 33, 40], appeared in fewer studies, highlighting the occasional significance of these species in specific regions.

The diversity of the Candida species was highest in Asia, with 12 different species documented, including rare species such as C. famata and C. lusitaniae. Africa consistently reported the classic species (C. albicans, C. glabrata, C. tropicalis, C. krusei) but had fewer rare species compared to Asia or the Americas. Europe and America demonstrated a mix of classic and rare Candida species but were less diverse than Asia (Fig. 3; Ref. [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40]).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Vulvovaginal candidiasis in pregnancy: the Candida species across different regions: Africa [5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13], North and South America [14, 15, 16, 17, 18], Asia [19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34], Australia [35], Europe [36, 37, 38, 39, 40].

These findings highlight both the commonalities and regional specificities of vaginal Candida infections worldwide, offering valuable insights for clinicians and researchers in tailoring diagnostic and therapeutic strategies.

The ages of the participants were not documented in three studies. The widest observed age range was 10–64 years, while the narrowest range was 20–38 years. Most studies reported age ranges falling within the reproductive years, typically 15–49, consistent with the demographic most commonly affected by vaginal candidiasis. Mean ages, when disclosed, ranged from 27 years to 34 years, with the majority clustering around 28–30 years. Seven studies provided mean ages with standard deviations, indicating variability within participant groups. In 13 studies, the mean ages were either not disclosed or were provided as approximate age ranges (e.g., 30+ years). These studies provided less specific information but generally aligned with the observed trends. Studies involving participants as young as 10 or as old as 64 suggest the inclusion of individuals outside the typical reproductive age group, although these cases were less common.

A total of 19 studies reported symptoms indicative of vaginal candidiasis, with discharge being the most prevalent symptom, noted in 13 studies. Pruritus (itching) was the next most prevalent symptom, noted in 11 studies; experiencing a burning sensation was reported in eight studies; dysuria (painful urination) and dyspareunia (pain during intercourse) were each mentioned in six studies; malodour was reported in four studies, while inflammation, manifested as erythema and colpitis, was observed in three studies. Less commonly reported symptoms included lower abdominal pain, plaques, and general irritation. This analysis underscores the prominence of discharge, pruritus, and burning sensation as hallmark symptoms of vaginal candidiasis, while highlighting variability in other reported manifestations. The risk factors for developing vaginal candidiasis in pregnancy were not documented in 20 studies. A total of 16 studies examined risk factors for vaginal candidiasis, revealing a diverse array of potential contributors. Among these, DM (more notably, values of Hemoglobin A1c/glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c)) was the most frequently reported risk factor, appearing in five studies [13, 21, 25, 28, 40]. The gestational week was also a recurrent factor, noted in five studies [10, 17, 18, 21, 25]; age emerged as significant in four studies [10, 18, 26, 30]; contraceptive use (including oral contraceptives) was highlighted in four studies [10, 14, 18, 28], while gravidity expressed in several pregnancies appeared also in four studies [10, 18, 21, 23]. Other notable factors mentioned twice were antibiotic use, with a particular emphasis on prolonged usage, and ethnicity. Several unique risk factors, such as socioeconomic status, douching, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), composition of intestinal microbiota, and tuberculosis, were mentioned in individual studies, illustrating the breadth of factors potentially influencing the development of vaginal candidiasis.

Table 2 (Ref. [3, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53]) presents studies that employed some form of VSQ for both symptomatic and asymptomatic patients. Most questionnaires were used to assess risk factors associated with vulvovaginal infections. Among all the studies presented, Dou N. and colleagues [41] evaluated the highest number of risk factors including age, marital status, family history, duration of residence, education level, parenting, history of pregnancy loss, wearing tight-fitting clothes, use of sanitary pads, vaginal douching, use of daily liners, frequency of sexual activity, pre-sex vulvar hygiene, number of sexual partners, type of permanent and, current address, underlying illnesses, methods of washing and drying underwear, swimming habits, menstrual history, sexual activity during period, daily showering routines and methods, birth control methods, frequency of shower during menstrual period, post-sex hygiene practices, underwear material, frequency of changing underwear, work environment. Most studies did not disclose the number of questions included, as these studies relied on non-standardized questionnaires used for data collection.

| Authors, year [Reference] | Type | Language/country | Number of questions | Tested parameters |

| America (n = 3) | ||||

| Erekson EA et al., 2013 [3] | Developed and validated | English, Japanese, Persian, Turkish, Chinese, Portuguese | 21 | Symptoms, emotions, life impact, and sexual impact |

| Yano J et al., 2019 [42] | General, not-validated | English | 13 | Demographics, symptoms, treatment, post-treatment outcomes |

| Brown JM et al., 2013 [43] | General, not-validated | English, Spanish | 18 | Demographics, symptoms, risk factors, treatment |

| Asia (n = 4) | ||||

| Fang X et al., 2007 [44] | General, not-validated | English (China) | ND ( | Demographics, risk factor |

| Dou N et al., 2014 [41] | General, not-validated | English (China) | ND ( | Demographics, risk factors |

| Li C et al., 2016 [45] | General, not-validated | English (China) | ND ( | Demographics, risk factors |

| Mahmoudi Rad M et al., 2011 [46] | General, not-validated | English (Iran) | ND | Demographics, risk factors |

| Africa (n = 4) | ||||

| Ekpenyong CE et al., 2012 [47] | General, not-validated | English (Nigeria) | ND ( | Demographics, risk factors |

| Mtibaa L et al., 2017 [48] | General, not-validated | English (Tunisia) | ND ( | Demographics, symptoms, risk factors, treatment |

| Djohan V et al., 2019 [49] | General, not-validated | English (Côte d’Ivoire) | ND ( | Demographics, symptoms, risk factors, treatment |

| Aniebue UU et al., 2018 [50] | General, not-validated | English (Nigeria) | ND | Demographics, symptoms, risk factors |

| Australia (n = 1) | ||||

| Bradshaw CS et al., 2005 [51] | General, not-validated | English | ND | Symptoms, risk factors |

| Europe and UK (n = 2) | ||||

| Grio R et al., 2004 [52] | General, not-validated | English (Italy) | ND | Risk factors |

| Bailey JV et al., 2008 [53] | General, not-validated | English (UK) | ND ( | Demographics, risk factors |

ND, not disclosed; VVC, vulvovaginal candidasis.

This study reviewed the signs, symptoms, and risk factors associated with VVC during pregnancy and provides a comprehensive analysis of the self-assessment VSQ in patients with vaginal infections. Vaginal infections during pregnancy can affect maternal health and potentially lead to adverse fetal outcomes. In addition to the literature reviewed on VVC and VSQs, Candida infections remain a major concern during pregnancy. This article highlights the importance of managing infections during pregnancy and proposes new methods for early detection, followed by laboratory confirmation to improve the diagnosis of VVC. These approaches could provide valuable insights for obstetric and gynecological practices.

The search strategy showed considerable variation among the included studies, along with significant regional diversity in the distribution of Candida species (Figs. 2,3). This review revealed a lack of sufficient data in the literature, resulting in the inclusion of only 36 studies. Additionally, population sizes varied extensively across studies, ranging from 80 patients [39] to 13,863 patients [14]. Notable age differences among participants were also observed, ranging from 10 years [17] to 64 years [29]. Moreover, the symptoms and signs were not investigated in 17 studies, while risk factors were not discussed in 20 studies. Furthermore, pregnancy outcomes were not analyzed. After performing a quality assessment of the included studies, we concluded that even though the overall quality of the evidence was “good”, many studies did not perform adequate statistical analysis, as these studies failed to account for confounding factors (JBI cross-sectional studies checklist in the Supplementary Table 1).

The study from 2016 [54] proposed several women-related risk factors, including pregnancy, hormone replacement, uncontrolled diabetes mellitus, immunosuppression, antibiotics, glucocorticoid use, and genetic predispositions. This 2016 study also highlighted behavioral risk factors such as the use of oral contraceptives, intrauterine devices, spermicides, condoms, as well as certain sexual practices, hygiene routines, and clothing habits [54]. Among all the risk factors discussed in the literature, diabetes was the most frequently reported, appearing in six studies. However, the central region of Saudi Arabia revealed that diabetes, pregnancy, and antibiotic usage were not found to be predisposing factors for candidiasis [55]. Additionally, multiple pregnancies have been identified as a risk factor for developing vaginal candidiasis, according to Faidah HS [23].

Through a systematic review of VSQs and specific Candida questionnaires, we identified 14 studies, of which only one was fully developed, validated, and available in multiple languages. However, none of these studies focused on pregnant women [3]. The parameters of the questionnaires varied; while most analysed demographic characteristics and risk factors, only seven also evaluated symptoms. The number of questions ranged from 10 to 30. In six studies, demographic characteristics and risk factors were assessed, but no symptoms or signs were addressed. All the VSQs were designed differently, making drawing coherent and consistent conclusions difficult.

A study from 2024 compared a computer-assisted self-interview with a clinician-based interview for vulvovaginal symptoms and found a strong similarity between self-administered computer interviews and clinician interviews [56]. This enables the prediction of candidiasis, particularly in individuals experiencing only mild symptoms. The use of questionnaires may also help guide primary patients and healthcare providers in clinical decision-making, allowing them to prioritize individuals who require further diagnostic testing. Moreover, accessibility plays a significant role in how effectively a self-assessment questionnaire can be utilized. The ability to distribute the questionnaire online or through healthcare applications (healthcare mobile apps) significantly expands the audience, making access to healthcare facilities more likely for individuals who might not otherwise seek care due to limited access, or those who reside in remote areas, even women who may feel uncomfortable visiting a clinic due to stigma or privacy concerns. One potential benefit is that patients take an active role in managing their health, increasing awareness of symptoms and risk factors, and better caring for their condition.

This is the first comprehensive review of the available literature on estimated signs, symptoms, and risks associated with vaginal candidiasis in pregnancy. The literature was found to lack sufficient data, and existing data varied across studies: sample sizes ranged from as few as 80 patients to as many as 13,863 patients; the participants had a significant age range, spanning ages from 10 to 64 years; symptoms and signs were not investigated in 17 studies, and risk factors were not discussed in 20 studies. This analysis identified a clear gap in the current research that warrants further investigation. Additionally, the obtained data highlights the importance of a uniform approach for Candida infection during pregnancy and the possible role of providing a specific questionnaire. We identified 14 studies, yet only one included a fully developed VSQ, which had been validated and was available in multiple languages. However, none of these 14 studies focused on pregnant women and the role of a VSQ. These aspects represent the key strengths of our work.

Nevertheless, we recognize several limitations. First, the review included only 36 studies. Further, nearly half of the studies did not examine the presence of symptoms and signs, while some failed to mention risk factors entirely. In addition, pregnancy outcomes were not assessed. Several studies lacked adequate statistical analysis and did not account for confounding factors, which affected the overall quality of evidence, despite being rated as “good”. Therefore, the scientific, clinical, and laboratory-based data utility in terms of the specific vaginal Candida infection problem in pregnancy remains limited.

Recognizing that VVC can significantly impact the quality of life of women and negatively affect newborns, future evidence-based practices should focus on developing a specific questionnaire. The universal adoption and validation of a Candida-specific VSQ, incorporating demographic characteristics, symptoms, and risk factors, while allowing patient participation and personalization, is essential. This may enhance current practices and lead to improved health outcomes.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

BS and VG contributed equally to this work and share first authorship. BS and VG: Conceptualization, methodology, data collection, writing original draft preparation. AJ: Data collection, review of the manuscript and critical revision of the manuscript. ND and BM: Literature search, interpretation of results, and critical revision of the manuscript. LP: Project administration, interpretation of results, and critical revision for important intellectual content. VAA: Supervision, project administration, critical revision for important intellectual content, substantial contributions to the design of the work, and final approval of the version to be published. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research was funded by The Science Fund of the Republic of Serbia Program Diaspora, Project “Combined Chrom agar Candida spp. and Streptococcus agalactiae test for screening vaginal colonization in pregnant women” - acronym CCA-CSAT-SVCPW, (grant number 6466878); and Program Ideas Project “Prediction, prevention and patients participation in diagnosis of selected fungal infections (FI): An implementation of novel method for obtaining tissue specimens” - acronym FungalCaseFinder, (grant number 7754282).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/CEOG37738.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.