1 Maternal-Infantile Department, Hospital of Gubbio and Gualdo Tadino (ASL 1 Umbria), 06024 Gubbio, Italy

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Hospital of Merano (SABES-ASDAA), 39012 Merano-Meran, Italy

3 Maternal-Infantile Department, Hospital of Verduno (ASL CN2), 12060 Verduno, Italy

4 Unit of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Maternal and Child Department, Sant’Anna University Hospital, 44124 Cona Ferrara, Italy

5 Division of Pathology, Hospital of Città di Castello (ASL 1 Umbria), 06012 Città di Castello, Italy

6 Department of Medicine and Surgery, University of Perugia, 06156 Perugia, Italy

Abstract

Knowledge about evolution of treated and untreated primary vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN) remains limited, as current guidelines recommend treatment. This study investigates the natural history of VaIN based on existing literature.

This study is a systematic review and descriptive meta-analysis. We searched the PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science (WoS), and Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) databases to identify clinical series reporting the no-regression rate(including persistence, recurrence, or progression events) of primary VaIN. We recorded data categorized by VaIN grade and treatment status. Clinical series that reported VaIN grade, follow-up time (median or mean of six months or more), treatment details, and whether treatment was performed were eligible for inclusion. Additionally, some internal hospital databases on VaIN were included. Data were pooled at each follow-up time point, using six-month intervals. From these pooled rates, trend curves were constructed to describe the natural history of treated (various therapies) and untreated low-grade and high-grade VaIN.

A total of 150 series were included in the data synthesis. Five subgroups were assessed for low-grade VaIN and twelve for high-grade VaIN. The estimated 5-year no-regression rate of untreated low-grade VaIN, predicted by trend curve, was 14.0% (95% confidence intervals (95% CI): 9.2%–44.0%), indicating that 86.0% of untreated low-grade VaIN would regress within 5-years. The 5-year no-regression rate for untreated high-grade VaIN, also predicted by trend curve, was 14.2% (95% CI: 10.2%–24.8%), indicating that 85.8% of untreated high-grade VaIN regress within 5-years. It cannot be determined to what extent treatment modifies the natural history of VaIN. Current assessments suggest that only low-level evidence is available on VaIN.

A large proportion of untreated VaIN lesions, regardless of grade, would resolve after 5 years of follow-up, with at least 14% of lesions unlikely to resolve.

The study has been registered on https://www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/view/CRD42023445810 (registration number: CRD42023445810).

Keywords

- vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia

- evolution

- treatment

- natural history

- systematic review

- care

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN) of high grade is the acknowledged precursor of vaginal cancer. VaIN is human papillomavirus (HPV) related, with HPV 16 and HPV co-infection being most involved in VaIN III lesions; VaIN is associated with cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) and with HPV related vulvar lesions [1]. Current opinion and recommendations advocate for treatments of VaINs [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Therefore, knowledge of untreated VaIN evolution is obviously poor and based on low quality level of evidence. Moreover, due to ethical concern, is also difficult to compare outcomes of VaINs among treated and untreated patients in further randomized studies.

In 1991, Aho et al. [9] published a paper on the natural history of untreated VaIN in a small cohort of 23 Finnish patients followed up for 3–15 years. The data showed that the occurrence of vaginal cancer was 8.7% (two cases: one was a previous low-grade VaIN, one was a previous high-grade VaIN), with a persistence rate of 18%. This paper is still relevant today, as no new data have emerged from untreated VaIN patients.

Subsequent studies on treated high-grade VaINs have been published since the work of Aho et al. [9]. For instance, the study by Sopracordevole et al. [10] is a multicentric observational data pool from Italian women treated for VaINs, reporting a rate of progression to invasive vaginal cancers of 9.8% (20 patients out of 205 eligible cases, as disclosed by authors). Yu et al. [11] reported two cases of invasive vaginal cancer out of 64 cases (3.1%) in a Chinese sample treated for VaINs, while Kim et al. [12] reported four cases of vaginal cancer out of 124 Korean patients (3.2%) treated for VaIN III. A rate of 6.1% vaginal cancer can be extracted from the US series of Gunderson et al. [13] (six cases out of 99 treated patients). All these results would intention-to-treat, making it difficult to understand the trend of vaginal cancer rates according to the follow-up time of high-grade VaINs. Moreover, they do not allow quantification of the expected advantages of treatments, which could appear poor when grossly compared with the older Finnish study of Aho et al. [9]. This conclusion is indirectly supported by some authors [3, 14], who suggest that expectation management could sometimes be proposed for high-grade VaINs.

Physicians and researchers need to understand how much a treatment should improve the natural regression rate of VaIN in order to evaluate the effectiveness of VaIN care. To do this, one should know the natural history of untreated VaINs. The present systematic review, therefore, aims to explore the natural history of VaINs, with and without treatment, based on the available literature.

The study plan was registered on the PROSPERO database (CRD42023445810).

The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration and received ethical approval from the Umbria Region Ethical Board the 28 of February 2022 (Prot. N. 24364/22/RI, CER Umbria Registry N. 4294/22).

This is a descriptive meta-analysis of the natural history of primary VaIN, categorized by disease severity (low-grade VaINs or VaIN I and high-grade VaINs—previously reported as VaIN II, VaIN III, vaginal carcinoma in situ) and treatment type. The study did not focus on a specific type of VaIN, such as those occurring after hysterectomy or intravaginal radiotherapy, because it aims to describe the real-world behavior of heterogeneous set of all VaIN types. Accordingly, sub-groups of VaINs were not assessed based on their location, extent, multifocality, or HPV status, although this information was extracted and reported when available. Recurrent VaINs (non-primary VaINs) were excluded from the analyses, as they were not considered informative regarding the evolution of in situ lesions of the vagina.

Two rounds of research were carried out on January 8, 2023, using PubMed, Scopus, WoS, and SciELO search engines. The phrases “Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia management” and “Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia treatment” were typed in search engines, to collect as much as possible articles on VaINs. There were no restrictions on language or publication dates.

The effect size of the meta-analysis was the rate of “no-regression” events (recurrence plus persistence plus progression cases, out of total observed cases) at any available follow-up time point. From these overall rates, the trend of no-regression of VaINs was constructed. The no-regression rate trend length was planned from a minimum of six months and every six months thereafter.

Eligible articles had to report:

-Primary VaIN case series with a minimum mean or median follow up period of six months;

-The grade of VaIN;

-Details about treatment or observation in each arm or single series;

-Mean or median follow up time, reported or estimable in each arm or single series;

-Groups and subgroups of VaINs in observational studies, randomized trials, and case series without a contrast group.

Each series of randomized trials or observational studies was considered a single dataset available for analysis if all cases in each arm shared the same treatments according to VaINs grade. Within single series, any sub-group of cases sharing the same treatments (or no treatment) was also eligible as a single series, if the extraction of a no-regression rate according to the grade and type of treatment of VaIN was allowed. The minimum number of cases in a single series was set to at least three. Along with eligible series from the literature, unpublished data on VaINs collected from hospital databases of the authors of this study were also planned for meta-analysis.

Quantitative data extraction and additional information collected from articles were performed by two authors (UI and AF). In case of disagreement, the issues were assessed and resolved through discussion between these authors.

No-regression rates (the effect size) of VaINs were planned to be extracted and calculated as follows:

-If all data were available at each follow-up time point (no missing data, no censored data), no-regression rates were calculated based on the total observed cases at each time point;

-In cases of censored data, Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed, and estimated rates of no-regression were extracted from time-to-event rate curves at each follow-up time point;

-If missing data could not be treated as censored, but events were reported at a specific time point, rates were calculated as intention-to-treat at each follow-up time point;

-If missing data could not be treated as censored and the time point of events occurrence could not be extracted, rates of no-regression were calculated as intention-to-treat for the entire dataset and analyzed at the median follow-up period only;

-If the median time were not available and the number of no-regression events for the entire dataset were known, no-regression rates were calculated as intention-to-treat and analyzed at the lower time point of the range only, or at the lower standard deviation limit only.

Authors decided to meta-analyze rates to the median time point or to lower limit of range or standard deviation due to the expected highly asymmetric distribution of no-regression events. This asymmetry is suggested by assessing data from Aho et al. [9], Sopracordevole et al. [10], Yu et al. [11], Kim et al. [12], and Gunderson et al. [13], as previously cited in the introduction. Additionally, hypothetical overestimation at short follow-up time points would be compensated by underestimates of long-term follow-up in the trend assessment of no-regression rates.

Some studies could report data as Kaplan-Meier curves. In these studies, time-to-event rates were planned to be extracted using the software Digitizelt, version 2.3.3 (© I. Bormann 2001 – 2016, http://www.digitizeit.de), from images.

When no events were observed in the series, the rate of rare events was estimated according to Quigley et al. [15].

Time-point intervals were set every six months and for an unplanned follow-up time. Time 0 was the time of diagnosis (in untreated VaINs series) or the time of treatment (in treated VaINs series). Follow-up time points lying in different time intervals were rounded down or up according to 6-month ranges (thereby compensating for any variability in data extraction estimates).

Qualitative analysis was conducted by two authors (UI and AF) who assigned quality scores using a modified GRADE system, as described below. In cases of disagreement discussion between both authors allowed data extraction and the final score. Given the descriptive nature of the study, the quality score was assigned to items deemed useful for assessing the natural history of VaIN. Specifically, authors would upgrade series with prospective enrollment, a description of sample age and menopausal status, and with a long lasting follow-up. Conversely, they chose to downgrade series with low sample size, those with 0 events observed, and those with short follow-up period. An overall score was then assigned to each series by summing individual item scores:

-Type of study from which the series originated: 3 points for randomized trials; 2 points for prospective studies; 1 point for retrospective studies; 0 points for studies with fewer than 15 cases, regardless of study type;

-Sample description: +1 point if menopausal status and median or mean age were both reported; –1 point if one or both were not reported;

-Number of events reported: +1 point if at least one event was reported; –1 point if no events were reported;

-Length of follow-up: 0 points for follow up below 12 months; +1 point for mean/median follow-up of at least 12 months; +2 points if mean/median follow up of at least 18 months; +3 points if mean/median follow-up of at least 24 months or more.

To test whether the quality score would affect the variability of the analysis, an exploratory meta-regression was planned between the quality score and standard error (on no-regression rates, calculated intention-to-treat, regardless of follow-up time). If the meta-regression was not significant, lower quality score series were not excluded a priori from the analysis. This decision was made to avoid assuming a priori that evidence in practice guidelines is poor, which could lead readers to underestimate the value of current practice guidelines.

After meta-regression, the case series were categorized according to VaIN grade (low-grade and high-grade VaIN) and treatments (no treatment and any reported treatment).

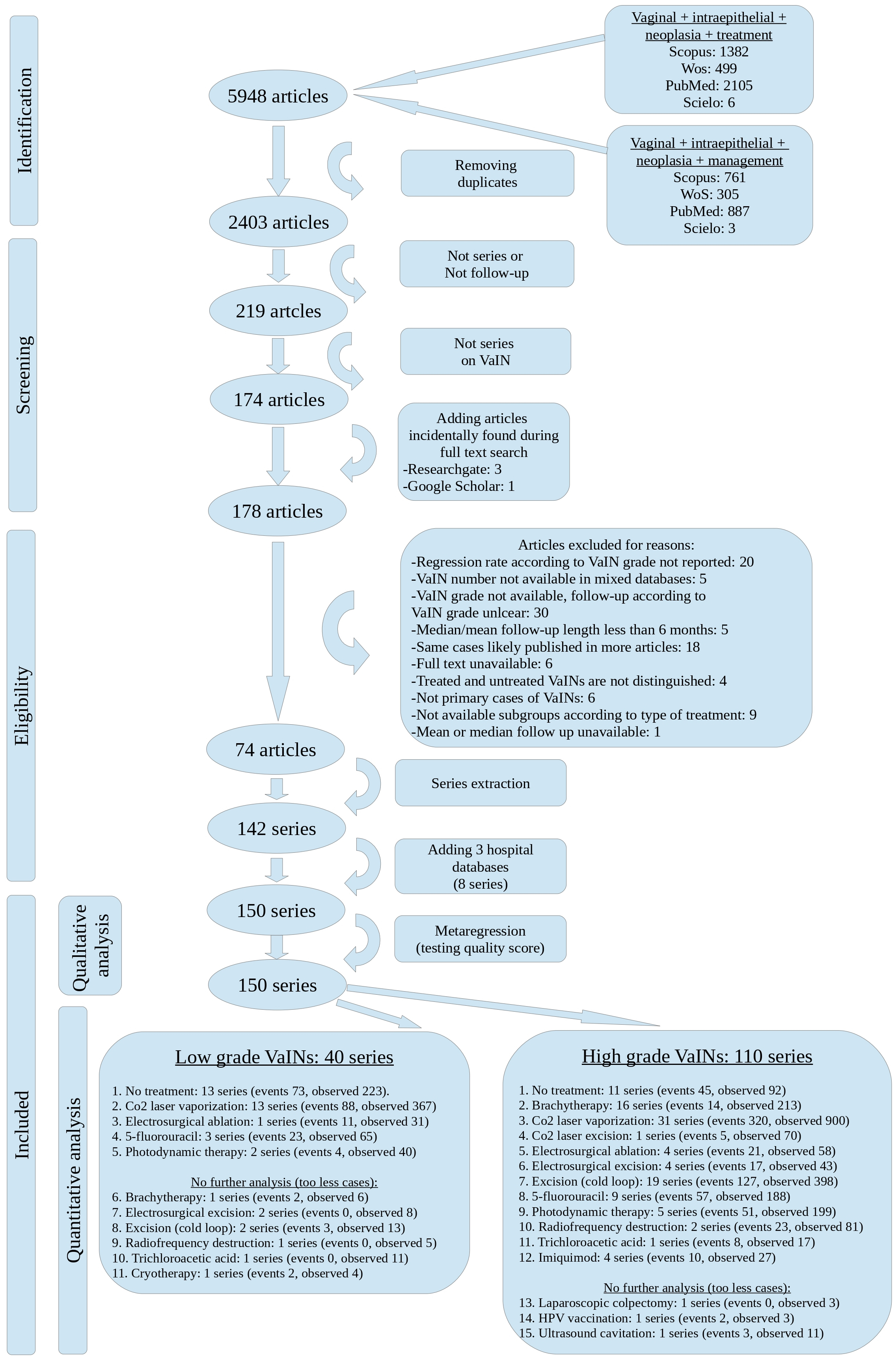

To reduce biases arising from low numerosity series, we exclude series with fewer than 15 cases when organizing sub-groups. On the contrary, pooled cases from multiple series or unique series with at least 15 observed cases at enrollment were included in further analysis. The sub-groups were illustrated in Fig. 1 (the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow-chart).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. PRISMA flow-chart of the systematic review. VaINs, Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia; PRISMA, the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses.

Data syntheses (the overall rates effect sizes of no-regression) were planned to be performed at each time point interval for each sub-group previously organized. Random effect models were used in cases of heterogeneity (at the quantitative level), while fixed models were applied if no heterogeneity (at the quantitative level) was found. The Q-statistic was used to assess the heterogeneity at the quantitative level. Heterogeneity at the qualitative level was accepted to better describe the behavior of the VaIN lesions in the real-world. Method for correcting non-random biases, as reported in [16], was applied to both fixed and random models. This technique limits the endogeneity bias arising from low sample sizes and selection bias due to non-homogeneous patients’ characteristics.

LibreOffice 7.0.3.1 (© 2000 – 2020 The LibreOffice foundation, Winterfeldtstraße 52, 10781 Berlin, Germany) was used for calculations.

The overall rates of no-regression and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) at each follow-up time point were intended to be plotted over time on Cartesian axes, for each sub-group. The main results were to be presented as trend shapes along with their 95% CI. Forest-plots with overall effect size were not planned as they could be confusing and not informative for the main aim of the study (the trends of no-regression of VaINs). Trend shapes (showing expected rates and their CIs) were derived from pooled and weighed data syntheses, and the best fit shapes were determined by minimizing the distance between observed pooled results and expected results.

Thus, the best trend shapes along with their CIs shapes would describe natural history of treated and untreated low-grade and high-grade VaINs.

The systematic research retrieved 5948 references. After removing duplicates, 2403 references were screened for studies on VaINs.

Two thousand one hundred eighty-three references were discarded because they did not focus on VaINs, while 45 references were discarded because they did not report VaIN series or follow-up. To the body of 174 references, four additional studies incidentally found during full-text research and published before January 8, 2023, were added. The subsequent phase of eligibility assessment (Fig. 1—PRISMA flow-chart) retrieved 74 eligible articles with 142 series. Eight more series were extracted from three hospital databases from UI, GS, CB authors’ health organizations and were added. Thus, the total number of series available for quality score assessment was 150.

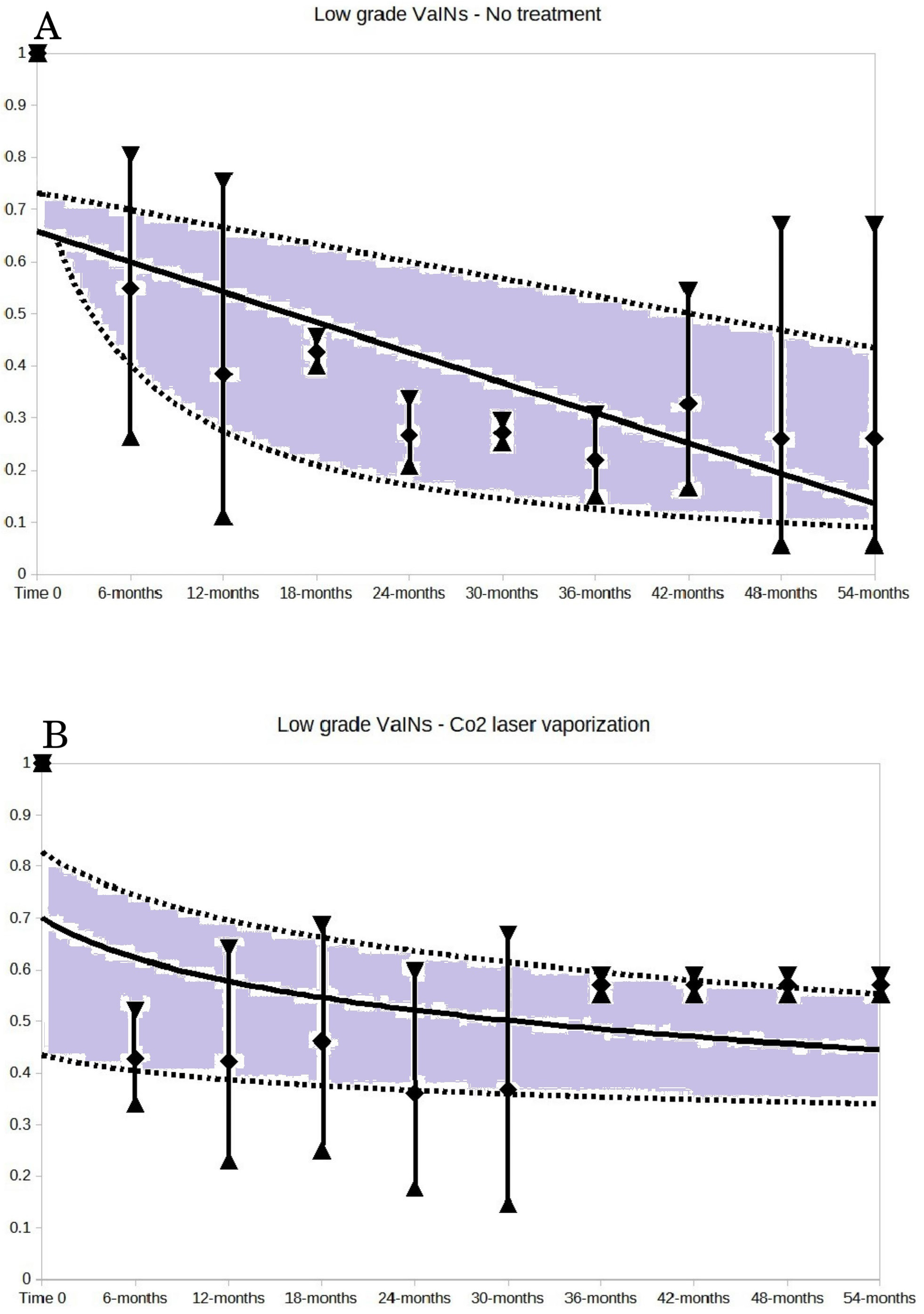

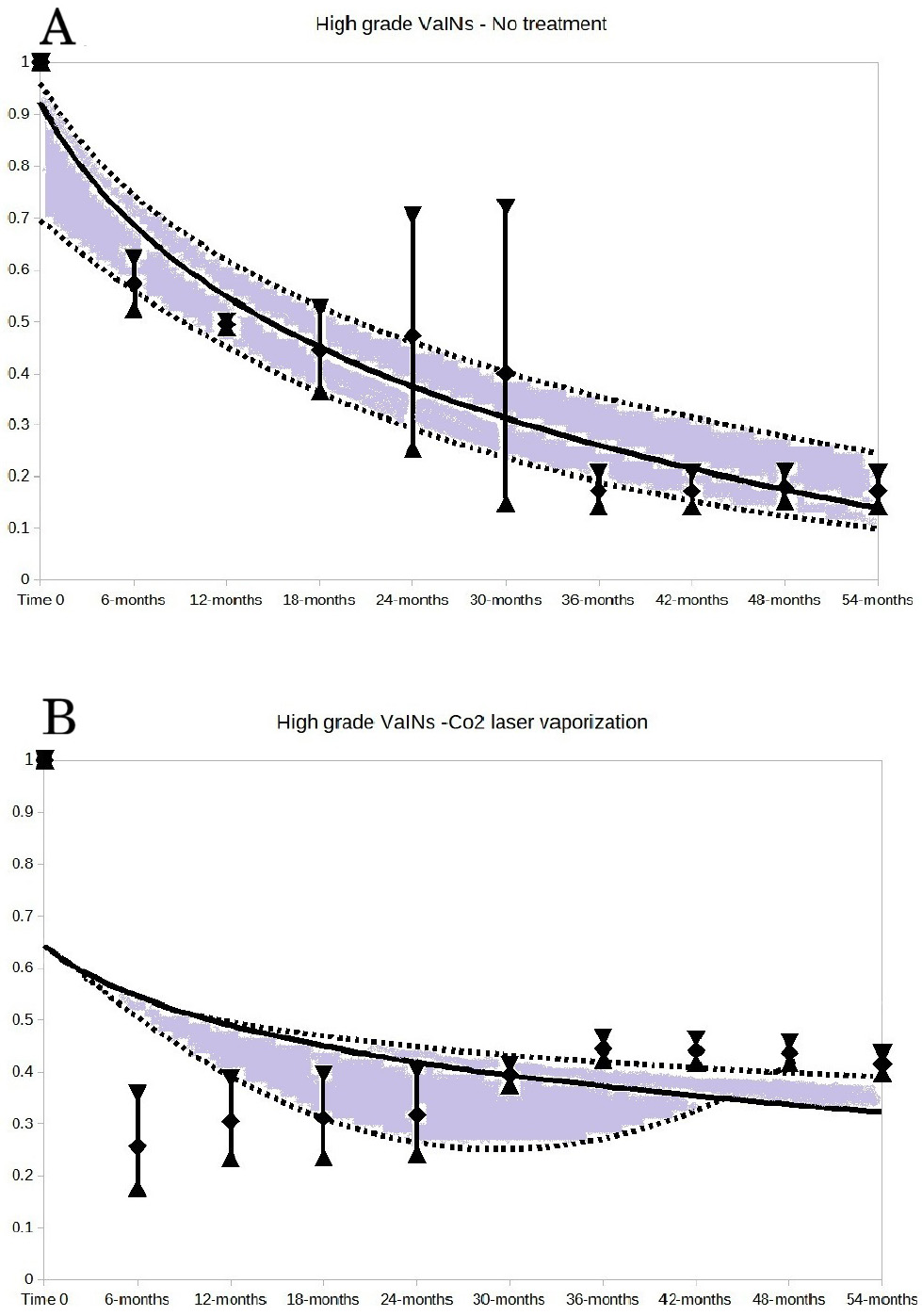

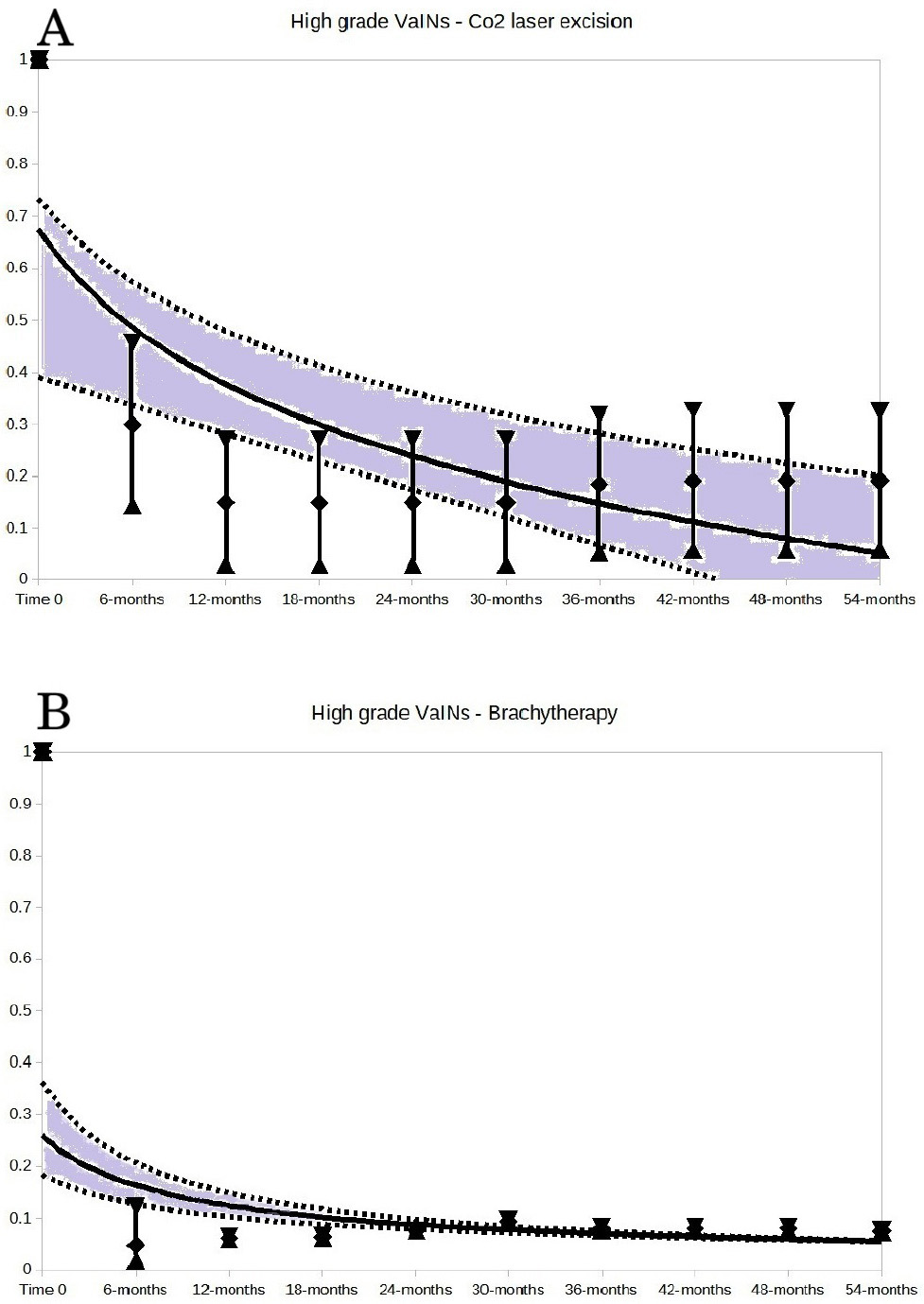

The key results are presented in Figs. 2,3,4. These Figures show the trends of no regression rates according to VaIN grade, no treatment, laser CO2 vaporization, laser CO2 excision and brachytherapy.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Low-grade VaINs: no treatment (A) and CO2 laser vaporization (B). For both A and B of the Figure, the vertical bars represent the weighted means and 95% CI of the no regression rates at each time point of follow-up. The follow-up time points are expressed in months. The trends were generated by selecting the best fitting regression lines of the weighted means of the no regression rates and their 95% CI. The trend shapes (of expected rates and their CI) were derived from these weighted mean no regression rates and their 95% CI: the best fitting shapes were determined by minimizing the distance of observed pooled results from expected results. The grey area between the 95% CI trend lines illustrates the probability space in which the no regression rate would fall, based on the follow-up time. The 14.0% value of no regression rate (reported in the text) is predicted by the trend line of untreated low-grade VaINs (A of the Figure) at the 54 months follow-up.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. High-grade VaINs: no treatment (A) and CO2 laser vaporization (B). For both A and B of the Figure, the vertical bars represent the weighted means and 95% CI of the no regression rates at each time point of follow-up. The follow-up time points are expressed in months. The 14.2% value of no regression rate (reported in the text) is predicted by the trend line of untreated high-grade VaINs (A of the Figure) at the 54 months follow-up.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. High-grade VaINs: CO2 laser excision (A) and brachytherapy (B). For both A and B of the Figure, the vertical bars represent the weighted means and 95% CI of the non-regression rates at each follow-up time point, expressed in months.

For the synthetic description of 150 series undergoing qualitative analysis, all relevant data are reported in tabular form in Table 1 (Ref. [9, 11, 12, 13, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84]). The rates of no-regression events in Table 1 were reported on an intention-to-treat basis, irrespective of follow up time, to enhance clarity.

| Author, year, country | Sampling | Case types | Available series | Mean age (years) | Menopausal status | Observed | Events | Follow-up (months) | Failure rate (ITT) |

| Aho M et al., 1991, Finland [9] | Retr. | Unspecified | -VaIN III: No treatment | 41.0* | n.r. | 5 | 1 | Mean: 64.8, range: 36–180 | 0.200 |

| Arcispedale Sant’Anna – Ferarra, 2020, Italy | Retr. | Unspecified | -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 32.3 | n.r. | 3 | 2 | Median: 42, range: 36–60 | 0.667 |

| -VaIN II–III: Radiofrequency ablation | 46.4 | n.r | 78 | 21 | Median: 16, range: 0–72 | 0.269 | |||

| ASL 1 Umbria, 2020, Italy | Retr. | Unspecified | -VaIN I: No treatment | 44.3 | n.r. | 18 | 6 | Median: 20, range: 1–40 | 0.333 |

| -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 56.7 | n.r | 3 | 2 | Median: 59, range: 17–73 | 0.667 | |||

| -VaIN: Radiofrequency ablation | 39.5 | n.r. | 5 | 0 | Median: 6, range: 3–8 | 0.000 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 39.0 | n.r. | 3 | 1 | Median: 6, range: 6–12 | 0.333 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Radiofrequency ablation | 45.7 | n.r. | 3 | 2 | Median: 9, range: 7–38 | 0.667 | |||

| ASL CN2, Ospedale Ferrero Verduno | Prosp. | Unspecified | -VaIN I: No treatment | 37.0 | n.r. | 3 | 0 | Median: 7, range: 6–24 | 0.000 |

| Audet-Lapointe P et al., 1990, Canada [17] | Retr. | VaIN de novo, VaIN associated to CIN or VIN, VaIN post-irradiation | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 42.4 | n.r. | 24 | 8 | Median: 24.5, range: 0–60 | 0.333 |

| -VaIN I: Cryotherapy | 44.0 | n.r. | 4 | 2 | Median: 33.5, range: 6–65 | 0.500 | |||

| -VaIN I: No treatment | 52.4 | n.r. | 5 | 3 | Median: 18, range: 0–71 | 0.600 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 55.9 | n.r. | 9 | 3 | Median: 42, range: 0–62 | 0.333 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 60.3 | n.r. | 12 | 6 | Median: 16.5, range: 0–118 | 0.500 | |||

| Benedet JL and Sanders BH, 1984, Canada [18] | Retr. | VaIN de novo, VaIN post-hysterectomy, VaIN post-irradiation, VaIN associated to CIN and VIN | -VaIN III: Excision | 55.0* | Reported | 56 | 35 | Median: 30, range: 12–60 | 0.625 |

| -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 55.0* | Reported | 27 | 4 | Median: 30, range: 12–60 | 0.148 | |||

| -VaIN III: Electrosurgical ablation | 55.0* | Reported | 13 | 6 | Median: 30, range: 12–60 | 0.462 | |||

| Blanchard P et al., 2011, France [19] | Retr. | VaIN III after CIN, after hysterectomy | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 50.0 | n.r. | 28 | 1§ | Median: 41, range: 0–284 | 0.036 |

| Bogani G et al., 2018, Italy [20] | Prosp. | Miscellaneous | -Vaginal HSIL: Laser vaporization | 53.0 | n.r. | 35 | 8§ | Median: 65, range: 6–120 | 0.228 |

| -Vaginal HSIL: Laser excision | 53.0 | n.r. | 70 | 5§ | Median: 65, range: 6–120 | 0.071 | |||

| Boonlikit S, 2022, Thailand [21] | Retr. | Unspecified | -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 50.8* | Reported | 18 | 11 | Median: 16.2, range: 4.5–36§ | 0.611 |

| -VaIN II–III: Imiquimod | 50.8* | Reported | 8 | 5 | Median: 18.8, range: 4.5–33.7§ | 0.625 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 50.8* | Reported | 33 | 17 | Median: 26.5, range: 4.5–59.2§ | 0.515 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical ablation | 50.8* | Reported | 8 | 2 | Median: 35.8, range: 4.5–38.4§ | 0.250 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical excision | 50.8* | Reported | 15 | 9 | Median: 6.6, range: 4.5–82.8§ | 0.600 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 50.8* | Reported | 17 | 8 | Median 39.8, range 4.5–67.4§ | 0.471 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Radiation therapy | 50.8* | Reported | 5 | 0 | Median: 57.3, range: 4.5–62.7§ | 0.000 | |||

| Choi YJ et al., 2013, Republic of Korea [22] | Prosp. | VaIN after hysterectomy for benign and malignant diseases | -VaIN II–III: Laparoscopic upper vaginectomy | 49.0 | n.r. | 3 | 0 | Mean: 20.7§, range: 11–29 | 0.000 |

| Choi MC et al., 2015, Republic of Korea [23] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy | -VaIN II–III: Photodynamic therapy | 49.6 | n.r. | 5 | 2 | Median: 119, range: 12–127 | 0.400 |

| Campagnutta E et al., 1999, Italy [24] | Prosp. | VaIN de novo, associated with CIN, HIV+/– | -VaIN I: No treatment | 40.3* | n.r. | 4 | 0 | Mean: 40, range: 30–52 | 0.000 |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 40.3* | n.r. | 4 | 3 | Median: 33.5, range: 30–52 | 0.750 | |||

| Copenhaver EH et al., 1964, USA [25] | Prosp. | VaIN after hysterectomy for cervical carcinoma in situ or invasive | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 63.0 | n.r. | 5 | 0 | Median: 28, range: 4–40 | 0.000 |

| Diakomanolis E et al., 1996, Greece [26] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy and VaIN de novo | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 12.0 | n.r. | 12 | 3 | Mean: 49, range: 35–82 | 0.250 |

| Fanning J et al., 1999, USA [27] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy for CIN or cervical cancer | -VaIN I: Electrosurgical excision | 50.0* | n.r. | 4 | 0 | Mean: 28.2§, range: 6–56 | 0.000 |

| Fiascone S et al., 2017, USA [28] | Retr. | High grade VaIN, miscellaneous cases | -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 52.3* | n.r. | 43 | 11§ | Median: 15.5, range: 3–73 | 0.256 |

| Field A et al., 2020, UK [29] | Retr. | Miscellaneous | -VaIN I: No treatment | 44.5* | n.r. | 29 | 6 | Mean: 22, range: 6–56 | 0.207 |

| -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 44.5* | n.r. | 3 | 0 | Mean: 18§, range: 6–24 | 0.000 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 45.2* | n.r. | 6 | 4 | All followed-up at 6 months | 0.667 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 44.3* | n.r. | 40 | 9 | Mean: 26, range: 6–73 | 0.225 | |||

| Frega A et al., 2007, Italy [30] | Prosp. | VaIN after hysterectomy for benign and malignant diseases. Radiotherapy | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 49.4 | n.r. | 14 | 0 | Mean: 36, range: 24–60 | 0.000 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 53.9 | n.r. | 30 | 10 | Mean: 36, range: 24–60 | 0.333 | |||

| Gallup DG et al., 1975, USA [31] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy mainly for malignant diseases | -VaIN III: Excision (various cold knife excisions) | Unclear | n.r. | 22 | 2 | Mean: 78§, range: 12–144 | 0.091 |

| Geelhoed GW et al., 1976, USA [32] | Prosp | VaIN after hysterectomy or treatment for cervical cancer | -VaIN III: No treatment | 59.2 | n.r. | 5 | 4 | Median: 6§, range: 6–30§ | 0.800 |

| Gonzalez-Sanchez JL et al., 1998, Mexico [33] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy or concomitant with CIN | -VaIN I: 5-fluorouracil | 54.0* | n.r. | 6 | 1 | Mean: 31, range: 12–84 | 0.167 |

| -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 54.0* | n.r. | 24 | 4 | Mean: 31, range: 12–84 | 0.167 | |||

| Graham K et al., 2007, UK [34] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy for benign and malignant diseases mainly | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 56.0 | Reported | 18 | 3§ | Median: 77, range: 32–220 | 0.167 |

| Gunderson CC et al., 2013, USA [13] | Retr. | VaIN synchronus with other genital neoplasias, VaIN after hysterectomy | -VaIN I: No treatment | 50.0* | n.r. | 26 | 14 | Median: 18, range: 1–194 | 0.538 |

| -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 50.0* | n.r. | 18 | 9 | Median: 18, range: 1–194 | 0.500 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 50.0* | n.r. | 44 | 12 | Median: 18, range: 1–194 | 0.273 | |||

| Haidopoulos D et al., 2005, Greece [35] | Prosp. | VaIN de novo and after previous treatment of warts | -VaIN II–III: Imiquimod | 50.1 | Reported | 7 | 3 | Median: 18.4, range: 5–31 | 0.429 |

| Han Q et al., 2022, China [36] | Prosp. | VaIN after hysterectomy and associated with genital HPV infection | -VaIN II–III: Photodynamic therapy | 51.0 | n.r. | 44 | 18 | Mean: 7.5§, range: 3–12§ | 0.409 |

| He MY et al., 2022, Hong Kong [37] | Retr. | Unspecified. Some cases onset after treatment for cancer | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 59.0 | Reported | 116 | 49 | Median: 49.5, range: 6–214 | 0.422 |

| Hernandez-Linares W et al., 1980, USA [38] | Retr. | VaIN after cancer treatments | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 54.0* | n.r. | 20 | 0 | Mean: 39§, range: 18–60§ | 0.000 |

| -VaIN III: Excision | 54.0* | n.r. | 6 | 0 | Mean: 39§, range: 18–60§ | 0.000 | |||

| Hodeib M et al., 2016, USA [39] | Retr. | Miscellaneous | -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 58.0* | n.r. | 4 | 3 | Mean: 71.5§, range: 9–240 | 0.750 |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 58.0* | n.r. | 13 | 5 | Mean: 71.5§, range: 9–240 | 0.385 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 58.0* | n.r. | 14 | 6 | Mean: 71.5§, range: 9–240 | 0.429 | |||

| Hu X et al., 2023, China [40] | Retr. | VaIN de novo, after hysterectomy, after CIN | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 51.5 | n.r. | 20 | 10 | Mean: 7.5§, range: 3–12 | 0.500 |

| Inayama Y et al., 2021, Japan [41] | Prosp. | VaIN high grade, mainly after cervical cancer | -VaIN II–III: Imiquimod | 53.8 | n.r. | 7 | 2 | Median: 20, range: 0–44 | 0.286 |

| Jobson VW and Homesley HD, 1983, USA [42] | Prosp. | VaIN after CIN or invasive cancers. Even hysterectomy | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 52.0 | n.r. | 23 | 5§ | Mean: 15, range: 6–27 | 0.217 |

| Kim MK et al., 2018, Republic of Korea [12] | Retr. | Previous CIN, previous hysterectomy or radiotherapy | -VaIN I: No treatment | 50.3* | Reported | 43 | 22 | Median: 44.6, range: 2.7–187.5 | 0.512 |

| -VaIN I: 5-flurouracil | 50.3* | Reported | 26 | 14 | Median: 44.6, range: 2.7–187.5 | 0.538 | |||

| -VaIN I: Excision | 50.3* | Reported | 9 | 2 | Median: 44.6, range: 2.7–187.5 | 0.222 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 50.3* | Reported | 13 | 6 | Median: 44.6, range: 2.7–187.5 | 0.462 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 50.3* | Reported | 24 | 15 | Median: 44.6, range: 2.7–187.5 | 0.625 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 50.3* | Reported | 52 | 17 | Median: 44.6, range: 2.7–187.5 | 0.327 | |||

| Kim HS et al., 2009, Republic of Korea [43] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy, mainly for CIN | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 48.0* | Reported | 24 | 3 | Median: 33, range: 10–115 | 0.125 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 48.0* | Reported | 44 | 15 | Median: 33, range: 10–115 | 0.341 | |||

| Kirwan P and Naftalin NJ, 1985, UK [44] | Retr. | VaIN associated with CIN | -VaIN II–III: 5-flurouracil | 34.5 | n.r. | 12 | 3 | Mean: 15, range: 4–42 | 0.250 |

| Koss LG et al., 1961, USA [45] | Prosp. | VaIN III post radiation for cervical cancer | -VaIN III: Excision | 51.7 | n.r. | 3 | 0 | Median: 10, range: 8–72 | 0.000 |

| Krebs HB, 1989, USA [46] | Prosp. | VaIN II–III HPV related, and post-radiation. | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 41.5 | n.r. | 22 | 6 | Mean: 33.6, range: 12–84 | 0.273 |

| -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 38.6 | n.r. | 37 | 7 | Mean: 33.6, range: 12–84 | 0.189 | |||

| Lenehan PM et al., 1986, Canada [47] | Retr. | VaIN HPV related, associated to genital HPV, post radiation, after hysterectomy | -VaIN I: Excision | 49.0* | n.r. | 4 | 1 | Mean: 52, range: 5–112 | 0.250 |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 49.0* | n.r. | 15 | 2 | Mean: 52, range: 5–112 | 0.133 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 49.0* | n.r. | 22 | 11 | Mean: 18, range: 3–72 | 0.500 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical ablation | 49.0* | n.r. | 10 | 2 | Mean: 52, range: 11–120 | 0.133 | |||

| Liao JB et al., 2011, USA [48] | Retr. | VaIN after radiotherapy, with or without previous hysterectomy | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 60.1 | n.r. | 4 | 3 | Median: 28.5, range: 9–37 | 0.750 |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 66.8 | n.r. | 5 | 4 | Median: 12, range: 2.5–79 | 0.800 | |||

| Lin H et al., 2005, Taiwan [49] | Prosp. | VaIN after hysterectomy for benign and malignant diseases. Some cases received radiotherapy | -VaIN I: Trichloroacetic acid | 59.0* | n.r. | 11 | 0 | Median: 23, range: 12–30 | 0.000 |

| -VaIN II–III: Trichloroacetic acid | 59.0* | n.r. | 17 | 8 | Median: 23, range: 12–30 | 0.471 | |||

| Llanos R et al., 1986, USA [50] | Prosp. | VaIN de novo | -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 44.0 | n.r. | 6 | 0 | All followed-up at 12 months | 0.000 |

| Luyten A et al., 2014, Germany [51] | Retr. | Miscellaneous | -VaIN II–III: Laser excision | 61.5* | Reported | 23 | 1 | Mean: 53.5§, range: 3–104 | 0.043 |

| MacLeod C et al., 1997, Australia [52] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy mainly | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 62.9 | n.r. | 7 | 1 | Median: 55, range: 8–75 | 0.143 |

| Massad LS, 2008, USA [53] | Retr. | VaIN with and without hysterectomy | -VaIN: No treatment | 53.0 | n.r. | 12 | 8 | Median: 20, range: 7–44 | 0.667 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 58.0* | n.r. | 6 | 4 | Median: 20, range: 7–44 | 0.667 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical excision | 58.0* | n.r. | 5 | 4 | Median: 20, range: 7–44 | 0.800 | |||

| Murakami K et al., 2017, Japan [54] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy for benign and malignant diseases | -VaIN III: Laser vaporization | 63.0* | n.r. | 4 | 3 | Median: 27, range: 1–70 | 0.750 |

| -VaIN III: Ultrasound cavitation | 63.0* | n.r. | 11 | 3 | Median: 27, range: 1–70 | 0.273 | |||

| Ogino I et al., 1998, Japan [55] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 50.8 | n.r. | 6 | 0 | Median: 62.5, range: 51–125 | 0.000 |

| Patsner B et al., 1993, USA [56] | Prosp. | VaIN after hysterectomy for benign and malignant diseases mainly | -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical excision | 39.0* | n.r. | 4 | 0 | All followed at 12 months | 0.000 |

| Perez CA et al., 1988, USA [57] | Retr. | Unspecified | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | Unclear | n.r. | 16 | 1 | Mean: 91.2, range: 6–128§ | 0.063 |

| Perrotta M et al., 2013, Argentina [58] | Retr. | History of CIN, some cases after hysterectomy | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 51.4 | n.r. | 21 | 3 | Median: 25, range: 12–78 | 0.143 |

| Petrilli ES et al. , 1980, USA [59] | Retr. | History of CIN-VIN treatments (radiation/hysterectomy) | -VaIN I: No treatment | Unclear | Reported | 5 | 1 | Mean: 8§, range: 6–10 | 0.200 |

| -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 50.2 | n.r. | 12 | 3 | Median: 22, range: 2–60 | 0.250 | |||

| Piovano E et al., 2015, Italy [60] | Retr. | Mainly de novo VaIN | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 38.0* | n.r. | 110 | 24 | Median: 5.2, range: 1.4–127.8 | 0.218 |

| -VaIN II: Laser vaporization | 38.0* | n.r. | 136 | 37 | Median: 6.6, range: 1–85.2 | 0.272 | |||

| -VaIN III: Laser vaporization | 38.0* | n.r. | 39 | 10 | Median: 3.6, range: 1.2–62 | 0.256 | |||

| Piver MS et al., 1979, USA [61] | Prosp. | VaIN post radiotherapy | -VaIN III: 5-fluorouracil | 52.3 | n.r. | 8 | 4 | Median: 47.5, range: 6§–83 | 0.500 |

| Policiano ACF et al., 2016, Portugal [62] | Prosp. | VaIN after treatments for CIN and cervical cancer | -VaIN high grade: Imiquimod | 42.2 | n.r. | 5 | 0 | Median: 36, range: 24–48 | 0.000 |

| Punnonen R et al., 1981, Finland [63] | Retr. | Unspecified | -VaIN II–III: Excision | 52.8* | n.r. | 6 | 0 | All followed-up at 60 months | 0.000 |

| -VaIN II–III: Brachytherapy | 52.8* | n.r. | 9 | 0 | All followed-up at 60 months | 0.000 | |||

| Shen F et al., 2020, China [64] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy for CIN-II–III | -VaIN high grade: Excision | 53.7* | n.r. | 55 | 9 | Median: 15, range: 2–88 | 0.164 |

| VaIN after hysterectomy for CIN-II–III | -VaIN high grade: Laser vaporization | 53.6* | n.r. | 58 | 32 | Median: 13, range: 2–80 | 0.552 | ||

| VaIN after hysterectomy for cervical cancer | -VaIN high grade: Excision | 53.7* | n.r. | 19 | 4 | Median: 15, range: 2–88 | 0.211 | ||

| VaIN after hysterectomy for cervical cancer | -VaIN high grade: Laser vaporization | 53.6* | n.r. | 35 | 15 | Median: 13, range: 2–80 | 0.429 | ||

| Song JH et al., 2014, Republic of Korea [65] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy for benign and malignant diseases | -VaIN I: Brachytherapy | 53.0* | n.r. | 6 | 2 | Median: 48, range: 4–122 | 0.333 |

| -VaIN II–III: Brachytherapy | 53.0* | n.r. | 19 | 2 | Median: 48, range: 4–122 | 0.105 | |||

| Song Y et al., 2015, China [66] | Retr. | Unclear | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 44.1* | n.r. | 115 | 32 | Mean: 29.0, St Dev: | 0.278 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 44.1* | n.r. | 41 | 16 | Mean: 29.0, St Dev: | 0.390 | |||

| Stafl A et al., 1977, USA [67] | Retr. | Unreported | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | n.r. | n.r. | 6 | 1 | Mean: 6.4, range: 3–12 | 0.167 |

| Stuart GC et al., 1988, Canada [68] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy mainly for benign diseases | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 46.4* | n.r. | 7 | 3§ | Mean: 14.4, range: 6–38 | 0.429 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 46.4* | n.r. | 20 | 7§ | Mean: 14.4, range: 6–38 | 0.350 | |||

| Su Y et al., 2022, China [69] | Retr. | VaIN associated to CIN | -VaIN low grade: Photodynamic therapy | 45.0* | Reported | 18 | 4 | Mean: 16.8, range: 12–38 | 0.222 |

| -VaIN high grade: Photodynamic therapy | 45.0* | Reported | 30 | 5 | Mean: 16.8, range: 12–38 | 0.167 | |||

| Teruya Y et al., 2002, Japan [70] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy for benign and malignant diseases | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 61.8 | n.r. | 13 | 0 | Median: 126.5, range: 35–218 | 0.000 |

| Terzakis E et al., 2011, Greece [71] | Retr. | VaIN in patients with previous CIN or cancer | -VaIN I: Electrosurgical excision | 55.0* | n.r | 4 | 0 | Median: 34.6, range: 16–60 | 0.000 |

| -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical excision | 55.0* | n.r. | 19 | 7 | Median: 34.6, range: 16–60 | 0.368 | |||

| van Poelgeest MIE et al., 2016, Netherlands [72] | Rand. | VaIN associated to HPV | -VaIN III: Vaccine | Not available | n.r. | 3 | 2 | Mean: 7.5§, range: 3–12 | 0.667 |

| Veloz-Martínez MG et al., 2015, Mexico [73] | Retr. | Unreported | -VaIN I: Electrosurgical ablation | 52.4* | n.r. | 31 | 11 | Mean: 9§, range: 6–12 | 0.355 |

| -VaIN I: 5-fluorouracil | 52.4* | n.r. | 33 | 8 | Mean: 9§, range: 6–12 | 0.242 | |||

| -VaIN I: No treatment | 52.4* | n.r. | 5 | 4 | Mean: 9§, range: 6–12 | 0.800 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical ablation | 52.4* | n.r. | 27 | 11 | Mean: 9§, range: 6–12 | 0.407 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 52.4* | n.r. | 22 | 7 | Mean: 9§, range: 6–12 | 0.318 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 52.4* | n.r. | 3 | 2 | Mean: 9§, range: 6–12 | 0.667 | |||

| Volante R et al., 1992, Italy [74] | Retr. | Unclear. Some cases after hysterectomy | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | Not available | n.r | 14 | 1 | Mean: 62§, range: 12–112 | 0.071 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | Not available | n.r. | 24 | 4 | Mean: 62§, range: 12–112 | 0.167 | |||

| Wang Y et al., 2014, China [75] | Retr. | Hysterectomy for CIN or vaginal cancer | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 50.4* | n.r. | 20 | 3 | Mean: 27.7, range: 19–39 | 0.150 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 50.4* | n.r. | 19 | 16 | Mean: 27.7, range: 19–39 | 0.842 | |||

| Wee WW et al., 2012, Singapore [76] | Retr. | VaIN de novo, some cases after hysterectomy | -VaIN I: No treatment | 40.3 | n.r. | 4 | 0 | Median: 19, range: 1–24 | 0.000 |

| -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 39.4 | n.r. | 5 | 2 | Median: 15, range: 9–22 | 0.400 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 31.0 | n.r. | 3 | 2 | Median: 16, range: 1–18 | 0.667 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 40.8 | n.r. | 7 | 2 | Median: 18, range: 6–22 | 0.286 | |||

| Woodman CB et al., 1984, UK [77] | Retr. | The majority of VaIN after hysterectomy, likely for malignant diseases | -VaIN high grade: Excision | 49.8 | n.r. | 4 | 2 | Median: 9.5, range: 7–72 | 0.500 |

| -VaIN high grade: Laser vaporization | 49.6 | n.r. | 13 | 7 | Median: 20, range: 3–60 | 0.538 | |||

| -VaIN high grade: Brachytherapy | 64.0 | n.r. | 4 | 0 | Median: 17, range: 6–36 | 0.000 | |||

| Woodman CB et al., 1988, UK [78] | Prosp. | Vaginal carcinoma in situ after hysterectomy | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 39.0 | Reported | 11 | 0 | Median: 26, range: 16–36 | 0.000 |

| Yao H et al., 2020, China [79] | Retr. | Miscellaeous | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 57.2 | n.r. | 20 | 7 | Mean: 13.55, range: 9–25 | 0.350 |

| Yu D et al., 2021, China [11] | Retr. | VaIN HPV related, some cases after hysterectomy | -VaIN I: No treatment | 49.8* | n.r. | 9 | 0 | Mean: 23.79, St Dev: 2.93 | 0.000 |

| -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 49.8* | n.r. | 8 | 3 | Mean: 23.79, St Dev: 2.93 | 0.375 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 49.8* | n.r. | 19 | 4 | Mean: 11.13, St Dev: 0.78 | 0.211 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Brachytherapy | 49.8* | n.r. | 5 | 1 | Mean: 11.13, St Dev: 0.78 | 0.200 | |||

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 49.8* | n.r. | 21 | 7 | Mean: 11.13, St Dev: 0.78 | 0.333 | |||

| Zeligs KP et al., 2013, USA [80] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy in the majority of cases | -VaIN I: No treatment | 47.6 | n.r. | 60 | 9 | Median: 34, range: 12–169 | 0.150 |

| -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 47.1 | n.r. | 14 | 1 | Median: 34, range: 12–169 | 0.071 | |||

| Zhang Q et al., 2008, China [81] | Retr. | VaIN after hysterectomy and HPV related | -VaIN II–III: Excision | Not available | n.r. | 6 | 4 | Mean: 7.5, range: 3–12 | 0.667 |

| Zhang T et al., 2022, China [82] | Prosp. | VaIN after hysterectomy in a half of cases | -VaIN I: Phodynamic therapy | 46.6 | n.r. | 22 | 0 | Mean: 9, range: 6–12 | 0.000 |

| -VaIN II–III: Phodynamic therapy | 41.7 | n.r. | 60 | 27 | Mean: 9, range: 6–12 | 0.450 | |||

| Zhang Y et al., 2022, China [83] | Retr. | VaIN de novo and after hysterectomy for benign and malignant diseases | -VaIN II–III: Phodynamic therapy | 41.9 | n.r. | 60 | 8 | Mean: 20.2, range: 12–42 | 0.133 |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 43.3 | n.r. | 40 | 10 | Mean: 20.2, range: 12–42 | 0.250 | |||

| Zolciak-Siwinska A et al., 2015, Poland [84] | Retr. | VaIN after Hysterectomy in the majority of cases | –VaIN II–III: Brachytherapy | 57.0 | n.r. | 20 | 1 | Median: 39, range: 14–115 | 0.050 |

CIN, cervical intraepithelial neoplasia; VIN, vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia; St Dev, standard deviation; ITT, Intention–to–treat; *unavailable datum for sub-groups; §datum recalculated by textual information; n.r., not reported; VaIN, vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia; HPV, human papillomavirus; HSIL, high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion; Retr., retrospective enrollment; Prosp, prospective enrollment.

Table 2 (Ref. [9, 11, 12, 13, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55, 56, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68, 69, 70, 71, 72, 73, 74, 75, 76, 77, 78, 79, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84]) describes the details of the quality score according to each item and each series. The total score for each series is reported in the right column in bold and was used as the independent variable for meta-regression analysis. The meta-regression did not yield significant results; therefore, all series were included in the sub-group phase organization. The median quality score was 3, with a minimum of –2 and a maximum of 6. Out of a hypothetical maximum score of 8 and a minimum score of –2, the proportion of series with a quality score greater than 4 (theoretically, higher quality series) was 16.7%, with four of them being low-grade VaIN series (10.0% of all low-grade series) and 21 were high-grade VaIN series (19.1% of all high-grade series).

| Author, year, country | Series | Type study | Sample description | 0 events observed | Mean/median follow-up length | Total |

| Aho M et al., 1991 Finland [9] | -VaIN III: No treatment | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 |

| Arcispedale Sant’Anna – Ferarra, 2020 Italy | -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Radiofrequency destruction | 1 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 2.0 | |

| ASL 1 Umbria, 2020 Italy | -VaIN I: No treatment | 1 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 3.0 |

| -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 | |

| -VaIN I: Radiofrequency ablation | 0 | –1 | –1 | 0 | –2.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 0 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Radiofrequency ablation | 0 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| ASL CN2-Ospedale Ferrero Verduno | VaIN I: No treatment | 0 | –1 | –1 | 0 | –2.0 |

| Audet-Lapointe P et al., 1990 Canada [17] | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 |

| -VaIN I: Cryotherapy | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 | |

| -VaIN I: No treatment | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 0 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 2.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 | |

| Benedet JL and Sanders BH, 1984, Canada [18] | -VaIN III: Excision | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 5.5 |

| -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 5.5 | |

| -VaIN III: Electrosurgical ablation | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 5.5 | |

| Blanchard P et al., 2011, France [19] | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 |

| Bogani G et al., 2018, Italy [20] | -Vaginal HSIL: Laser vaporization | 2 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 5.0 |

| -Vaginal HSIL: Laser excision | 2 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 5.0 | |

| Boonlikit S, 2022, Thailand [21] | -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +1 | 4.5 |

| -VaIN II–III: Imiquimod | 0 | +0.5 | +1 | +2 | 3.5 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 5.5 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical ablation | 0 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 4.5 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical excision | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | 0 | 2.5 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 5.5 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Radiation therapy | 0 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 4.5 | |

| Choi YJ et al., 2013, South Korea [22] | -VaIN II–III: Laparoscopic upper vaginectomy | 0 | –1 | –1 | +2 | 0.0 |

| Choi MC et al., 2015, South Korea [23] | -VaIN II–III: Photodynamic therapy | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 |

| Campagnutta E et al., 1999, Italy [24] | -VaIN I: No treatment | 0 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 1.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 | |

| Copenhaver EH et al., 1964, USA [25] | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 0 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 1.0 |

| Diakomanolis E et al., 1996, Greece [26] | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 5.0 |

| Fanning J et al., 1999, USA [27] | -VaIN I: Electrosurgical excision | 0 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 1.0 |

| Fiascone S et al., 2017, USA [28] | -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 1 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 2.0 |

| Field A et al., 2020, UK [29] | -VaIN I: No treatment | 1 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 3.0 |

| -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 0 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 1.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 0 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 | |

| Frega A et al., 2007, Italy [30] | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 2 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 3.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 2 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 5.0 | |

| Gallup DG et al., 1975, USA [31] | -VaIN III: Excision (various cold knife excisions) | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 5.0 |

| Geelhoed GW et al., 1976, USA [32] | -VaIN III: No treatment | 0 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Gonzalez-Sanchez JL et al., 1998, Mexico [33] | -VaIN I: 5-fluorouracil | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 | |

| Graham K et al., 2007, UK [34] | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 1 | +1 | +1 | +3 | 6.0 |

| Gunderson CC et al., 2013, USA [13] | -VaIN I: No treatment | 1 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 3.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 0 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 2.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 1 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 3.0 | |

| Haidopoulos D et al., 2005, Greece [35] | -VaIN II–III: Imiquimod | 0 | +1 | +1 | +2 | 4.0 |

| Han Q et al., 2022, China [36] | -VaIN II–III: Photodynamic therapy | 2 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 2.0 |

| He MY et al., 2022, Hong Kong [37] | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | +1 | +1 | +3 | 6.0 |

| Hernandez-Linares W et al.,1980 USA [38] | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 1 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 2.0 |

| -VaIN III: Excision | 0 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 1.0 | |

| Hodeib M et al., 2016, USA [39] | -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 | |

| Hu X et al., 2023, China [40] | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 1.0 |

| Inayama Y et al., 2021, Japan [41] | -VaIN II–III: Imiquimod | 0 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 2.0 |

| Jobson VW and Homesley HD, 1983, USA [42] | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 2 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 3.0 |

| Kim MK et al., 2018, South Korea [12] | -VaIN I: No treatment | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 5.5 |

| -VaIN I: 5-flurouracil | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 5.5 | |

| -VaIN I: Excision | 0 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 4.5 | |

| -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 5.5 | |

| -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 5.5 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 5.5 | |

| Kim HS et al., 2009, South Korea [43] | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 5.5 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 5.5 | |

| Kirwan P and Naftalin NJ, 1985, UK [44] | -VaIN II–III: 5-flurouracil | 1 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 2.0 |

| Koss LG et al., 1961, USA [45] | -VaIN III: Excision | 0 | –1 | –1 | 0 | –2.0 |

| Krebs HB, 1989, USA [46] | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 | |

| Lenehan PM et al., 1986, Canada [47] | -VaIN I: Excision | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 3.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical ablation | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 | |

| Liao JB et al., 2011, USA [48] | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 0 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 1.0 | |

| Lin H et al., 2005, Taiwan [49] | -VaIN I: Trichloroacetic acid | 2 | –1 | –1 | +1 | 2.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Trichloroacetic acid | 2 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 4.0 | |

| Llanos R et al., 1986, USA [50] | -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 0 | –1 | –1 | +1 | –1.0 |

| Luyten A et al., 2014, Germany [51] | -VaIN II–III: Laser excision | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +3 | 5.5 |

| MacLeod C et al., 1997, Australia [52] | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 |

| Massad LS, 2008, USA [53] | -VaIN: No treatment | 1 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 3.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 0 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 2.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical excision | 0 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 2.0 | |

| Murakami K et al., 2017, Japan [54] | -VaIN III: Laser vaporization | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 |

| -VaIN III: Ultrasound cavitation | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 | |

| Ogino I et al., 1998, Japan [55] | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 0 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 1.0 |

| Patsner B et al., 1993, USA [56] | -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical excision | 0 | –1 | –1 | +1 | –1.0 |

| Perez CA et al., 1988, USA [57] | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 |

| Perrotta M et al., 2013, Argentina [58] | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 |

| Petrilli ES et al., 1980, USA [59] | -VaIN I: No treatment | 0 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 1 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 3.0 | |

| Piovano E et al., 2015, Italy [60] | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 1.0 |

| -VaIN II: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 1.0 | |

| -VaIN III: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 1.0 | |

| Piver MS et al., 1979, USA [61] | -VaIN III: 5-fluorouracil | 0 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 1.0 |

| Policiano ACF et al., 2016, Portugal [62] | -VaIN high grade: Imiquimod | 0 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 1.0 |

| Punnonen R et al., 1981, Finland [63] | -VaIN II–III: Excision | 0 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 1.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Brachytherapy | 0 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 1.0 | |

| Shen F et al., 2020, China [64] | -VaIN high grade: Excision | 1 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 2.0 |

| -VaIN high grade: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 2.0 | |

| -VaIN high grade: Excision | 1 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 2.0 | |

| -VaIN high grade: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 2.0 | |

| Song JH et al., 2014, South Korea [65] | -VaIN I: Brachytherapy | 0 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 1.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Brachytherapy | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 2.0 | |

| Song Y et al., 2015, China [66] | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 | |

| Stafl A et al., 1977, USA [67] | -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 0 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Stuart GC et al., 1988, Canada [68] | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 0 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 1.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 2.0 | |

| Su Y et al., 2022, China [69] | -VaIN low grade: Photodynamic therapy | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +1 | 3.5 |

| -VaIN high grade: Photodynamic therapy | 1 | +0.5 | +1 | +1 | 3.5 | |

| Teruya Y et al., 2002, Japan [70] | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 1 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 2.0 |

| Terzakis E et al., 2011, Greece [71] | -VaIN I: Electrosurgical excision | 0 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 1.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical excision | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 | |

| van Poelgeest MIE et al., 2016, The Netherlands [72] | -VaIN III: Vaccine | 0 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Veloz-Martínez MG et al., 2015, Mexico [73] | -VaIN I: Electrosurgical ablation | 1 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 1.0 |

| -VaIN I: 5-fluorouracil | 1 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 1.0 | |

| -VaIN I: No treatment | 0 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Electrosurgical ablation | 1 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 1.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: 5-fluorouracil | 1 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 1.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 0 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Volante R et al., 1992, Italy [74] | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 | |

| Wang Y et al., 2014, China [75] | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 | |

| Wee WW et al., 2012, Singapore [76] | -VaIN I: No treatment | 0 | –1 | –1 | +2 | 0.0 |

| -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 0 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 1.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 0 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 1.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 0 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 3.0 | |

| Woodman CB et al., 1984, UK [77] | -VaIN high grade: Excision | 0 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| -VaIN high grade: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 3.0 | |

| -VaIN high grade: Brachytherapy | 0 | –1 | –1 | +1 | –1.0 | |

| Woodman CB et al., 1988, UK [78] | -VaIN III: Brachytherapy | 2 | +1 | –1 | +3 | 5.0 |

| Yao H et al., 2020, China [79] | -VaIN I: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | +1 | 2.0 |

| Yu D et al., 2021, China [11] | -VaIN I: No treatment | 0 | –1 | –1 | +3 | 1.0 |

| -VaIN I : Laser vaporization | 0 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 3.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 1 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 1.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Brachytherapy | 0 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| -VaIN II–III: Laser vaporization | 1 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 1.0 | |

| Zeligs KP et al., 2013, USA [80] | -VaIN I: No treatment | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: No treatment | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 | |

| Zhang Q et al., 2008, China [81] | -VaIN II–III: Excision | 0 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Zhang T et al., 2022, China [82] | -VaIN I: Phodynamic therapy | 2 | –1 | 0 | 0 | 1.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Phodynamic therapy | 2 | –1 | +1 | 0 | 2.0 | |

| Zhang Y et al., 2022, China [83] | -VaIN II–III: Phodynamic therapy | 1 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 3.0 |

| -VaIN II–III: Excision | 1 | –1 | +1 | +2 | 3.0 | |

| Zolciak-Siwinska A et al., 2015, Poland [84] | -VaIN II–III: Brachytherapy | 1 | –1 | +1 | +3 | 4.0 |

The quality score was assigned by summing and subtracting the point given to each issue of a modified GRADE score. Total score point is highlighted in bold on the last right column of the Table. The +0.5-quality score point had been decided by authors changing previous plan if average age has reported only at aggregate level (no sub-groups average age) and if hormonal status was disclosed.

Low-grade VaIN series and high-grade VaIN series were divided (Fig. 1, bottom boxes). Low-grade VaIN series were grouped according to treatment, resulting in 11 sub-groups. Among these 11 sub-groups, only five were eligible for further analysis, as they included more than 15 cases at enrollment (single series or pooled data series).

Similarly, high-grade VaIN series were grouped according to treatment, resulting in 15 sub-groups, of which 12 were eligible for further analysis since they included more than 15 cases at enrollment. In the lower boxes, Fig. 1 reports the sub-group arrangement, displaying which sub-groups were not further analyzed. Fig. 1 also reports the number of events and the total number of observed cases for each sub-group.

The maximum length of follow-up was set to five years, as follow-up data extending beyond five years for untreated patients and for several sub-groups of treated patients were not available.

Low-grade VaINs without treatment totaled 223 cases. The no-regression cases were 73. The estimated 5-year no-regression rate of untreated low-grade VaINs, predicted by trend shape (Fig. 2A: 54 months or 5 years’ time point follow-up) was 14.0% (95% CI: 9.2%–44.0%). Fig. 2 also presents the trend of no-regression rates for low-grade VaINs treated with CO2 laser vaporization (part B). The sub-group of low-grade VaIN treated by electrosurgical ablation encompassed only one series, with only a 6-month follow-up. It was decided not to plot the trend shape for electrosurgical ablation in low-grade VaINs, as it would not informative long-term outcomes, while trends of low-grade VaINs treated with 5-fluorouracil and photodynamic therapy were inconclusive (too large CIs).

High-grade VaIN cases that did not undergo any treatment totaled 92. The no-regression events were 45. The trend of no-regression rate is reported in Fig. 3. The 5-year no-regression rate for untreated high-grade VaINs predicted by trend shape (Fig. 3A) was 14.2% (95% CI: 10.2%–24.8%). Trends of no-regression rates for high-grade VaINs, treated with CO2 laser vaporization, CO2 laser excision, and brachytherapy were reported in Fig. 3B and Fig. 4. Other high-grade VaINs treatments were also inconclusive (too large CIs) and trends were not reported. However, it can be observed higher regression rates before 24 months of follow up for all treatments. The treatments assessed included: CO2 laser vaporization (Fig. 3B), CO2 laser excision (Fig. 4A), brachytherapy (Fig. 4B), loop electrosurgical ablation, loop electrosurgical excision, radiofrequency destruction, cold loop excision, imiquimod application, 5-fluorouracil application, trichloroacetic acid application, and photodynamic therapy after 5-aminolevulinic acid application.

Higher heterogeneity is evidenced by wider CI limits in many low-grade and high-grade VaIN sub-groups of treated women. The I2 indexes of heterogeneity were not reported because not informative. High heterogeneity is the result of intentional a priori acceptance of heterogeneous series at a qualitative level in this comprehensive descriptive analysis, which aims to portray the real-world natural history of VaINs. Consequently, a clear regression trend for many treatments was not achievable. Additionally, for photodynamic therapy, no studies included follow-up longer than 12 months.

This study assessed the natural history of primary high-grade and low-grade VaINs, with and without therapies. We remark that current knowledge, recommendations, opinions are aligned in advocating to treat VaIN [2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. The methodological diversity and heterogeneity across the included case series and cohorts in this descriptive meta-analysis result in evidence of low certainty, limiting robust conclusions. Therefore, results of the present work do not change current practice in managing vaginal intraepithelial lesions.

Even limited scientific evidence deserves assessment, but readers should critically evaluate the quality and reliability of such evidence. Dismissing poor scientific evidence solely based on its quality would hinder scientific progress, but uncritically accepting such evidence could lead to incorrect conclusions and potentially harmful clinical recommendations. Therefore, a defeatist interpretation of our results would suggest that many treatments for VaINs are ineffective or have minimal efficacy. From the other hand, biases may provoke criticism of our work. In the latter case, detractors might conclude that our results are weak, at least as suggestions available in current practice guidelines [2, 3], which are based on the same weak evidence as the current work.

Despite the weaknesses of the present review (which will be further addressed below), we would like to highlight its strengths. This is a comprehensive review, based on a systematic approach, aimed at minimizing biases to provide real-world insights into VaINs evolution. The review has also revealed that a significant gap exists in outcome measures regarding the efficacy of VaINs treatments, and that subjective judgment and individual expertise in treating various VaINs conditions could impact the reported outcomes. Therefore, current treatments are largely empirical, based on the acknowledged rationale that treating in situ lesions can prevent the onset of a cancer. However, it is suggested that the progression of vaginal lesions over time indicates that a follow up of more than 3 years should be considered to prevent VaIN relapses or their progression later in the patient’s life.

Regarding a more in-depth assessment of the study’s weaknesses, we first refer to the summary of studies reported in Table 1: numerous studies have presented various types of primary VaINs, but many lack details on VaIN outcomes in specific circumstances, such as VaINs diagnosed post-hysterectomy, following prior treatments for CIN, in immunodeficient patients, or in cases of multifocal lesions, extensive spread, or specific locations. Therefore, the literature includes data from inadequate or very limited series, with several studies lacking control groups, the absence of randomized trials, and some cases sourced from outdated literature. These findings underscore the concern of insufficient evidence in the scientific understanding of VaIN. Surprisingly, our review also revealed that despite the poor quality, biased, or outdated nature of the studies, there is also a lack of studies reporting a comprehensive set of VaIN outcomes essential for drawing reliable conclusions on VaIN management.

Additionally, authors believe that data from the available literature can only be pooled for a descriptive view of the trends in VaIN behavior over time without any comparative analysis (another limitation for making speculations). In untreated patients, a sluggish trend toward spontaneous resolution of both high-grade and low-grade VaINs is observed within a 5-year period. The estimated 5-year no-regression rate for both low-grade and high-grade VaINs is approximately 14% (see Fig. 2A, and Fig. 3A). There is greater uncertainty regarding recurrence rates between 24 and 36 months of follow up in high-grade VaINs, while less uncertainty is noted in low-grade VaINs during the same follow up period. This behavior suggests that the key time point for providing a prognosis on VaIN regression would be at 2–3 years of follow up. Based on trend shapes affected by large CIs of many treatments (results not shown), it remains unclear whether treatments could improve the outcomes of both high-grade and low-grade VaINs, although brachytherapy and CO2 laser excision appear to perform better than other therapies for high-grade VaIN lesions.

The CO2 laser excision in high-grade VaINs encompasses only one eligible series, suggesting a 5-year no-regression rate lower than that of other treatments for high-grade VaIN, while brachytherapy encompasses 16 series and shows fewer than 10% of expected no-regression events in a 5-year follow-up, apparently lower than untreated high-grade VaINs. Brachytherapy can provoke some side effects and is not suggested as the first-line choice for treating VaINs [2]. Other treatments would not seem to significantly contribute to the no-regression rate at the 5-year follow-up, but uncertainty is large. However, when comparing no-recurrence rates within 30 months among treated and untreated patients, it appears that treatments may offer better no-recurrence rates before the 2-year follow-up. This behavior can primarily be explained by the natural history of HPV infection, which tends to persist in a significant proportion of infected individuals after three years of contagion [85].

Numerous treatments for VaINs have been reported in the literature [4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 72]. They can be grouped into three categories: (1) excisional (cold knife excision of the abnormal vaginal areas or upper or total vaginectomy with or without hysterectomy, laparoscopic electrosurgical excision of the vagina, loop electrosurgical procedures using electrocoagulation or radiofrequency, laser excision), (2) destructive (surgical ablation with radiofrequency, electrocoagulation, cryotherapy, ultrasonographic cavitational aspiration, laser destruction, radiotherapy, photodynamic ablative therapy, cytotoxic therapies), and (3) immunomodulatory (imiquimod). There is no consensus on the best treatment or the optimal combination of treatments for curing VaIN [2], and it is commonly accepted that high-grade VaINs should be treated excisionally, while low-grade VaINs can be managed more conservatively. These policies are analogous to those applied for CINs, as VaINs are primarily HPV-related. Treatment failures have been noted in wide or multifocal lesions or lesions localized within the vaginal cuff after hysterectomy where it is technically challenging to eliminate all abnormal areas [86, 87]. Multivariate analysis in Sillman et al. [87] study did not show any relationship between immunosuppression and VaIN degree on VaIN progression to invasive cancer. Other studies (for example Kim et al. [12]), however, strengthen the relationship between VaIN grade and the risk of progression to invasive cancer. The finding by Sillman et al. [87] would be in agreement with our no regression rate estimates, which demonstrate the same 5-year evolution for both low-grade and high-grade VaINs. Taken together, along with what was reported by Gurumurthy et al. [3] and by Ratnavelu et al. [14] (expectant management for high-grade VaINs sometimes possible), this finding leads us to consider that VaIN lesions may not have the same natural history as CINs, and that the same approach as CINs could be theoretically incorrect in both low-grade and high-grade VaINs. Undoubtedly, however, the natural history of HPV infection would be the same for VaINs and for CINs, so the behavior of VaINs lesions would not only be in related to HPV infection.

An issue concerning the prognosis of VaINs may be related to the quality of colposcopy. Some authors have reported that the quality of colposcopy for VaIN lesions is poor [88, 89]. If colposcopy is unable to detect the more severe areas of VaIN, the colposcopist is not able to accurately identify and biopsy the worst grade of VaIN, which can impact the type of treatment and the outcome of the VaIN.

Another issue is the type of HPV affecting the patient. Studies have shown that certain types of HPV are more commonly detected in VaIN lesions compared to CIN [90], and high-grade VaINs are often associated with high risk HPV types [1, 91]. If physicians are unaware of the specific HPV type infecting the patients, they may treat all VaINs based solely on VaIN grade. However, VaINs of the same grade but caused by different HPV types may have varying outcomes.

During the revision process, peers have raised concerns about the selection bias. The selection bias may affect the trend shapes in all sub-groups, as it can be hypothesized that treatments would be individualized according to the severity of VaINs assessed by colposcopists in each case. This approach aligns with current practice guidelines on VaIN management [2]. Therefore, it is difficult to feel, for example, that multifocal or extensive VaIN lesions, regardless of their grade, have not been treated or are treated more conservatively than localized VaINs. Additionally, the selection bias may explain the observed similar trends for treated and untreated low- and high-grade VaINs. To limit the impact of this bias, authors have applied the tool reported in [16] and other corrections in data processing, as already stated above, but they were unable to eliminate such a confounder.

Moreover, scholars may disagree about the a priori decision to include heterogeneous series at a qualitative level to better describe the real-world behavior of VaINs evolution. While we recognize that this choice may be questioned, it is important to note that similar heterogeneous patient samples in different and poor studies have been evaluated to inform guidelines on the treatment of VaINs [2].

Finally, careful attention should be paid while interpreting trends of no-regression rates reported in this article, particularly concerning the risk of VaIN progression to invasive cancer. The assessment of the progression of VaINs to cancer was not the aim of this study. Therefore, we calculated the rate of no regression by summing all events of no regression (including progression to cancer) extracted from various series. These series typically do not report disaggregated data on relapses, persistence, and progression to cancer. It should be expected that the no-regression events reported for low-grade VaINs would not consist of the same proportions of persistence, relapses, and evolution observed in high-grade VaINs, even if the trends of no regression seem quite similar. It is reasonable to expect that the progression to cancer would be higher for high-grade VaINs than for low-grade VaINs, as current opinion suggest to feel [2, 5, 6, 7, 8]. Using data from Aho et al. [9] and composing them with our findings, we can estimate a 5-year probability of progression to cancer in untreated low-grade and high-grade VaINs: 0.8% (95% CI: 0.0%–7.1%) for low-grade VaINs and 5.7% (95% CI: 0.0%–20.6%) for high-grade VaINs. However, this simulation cannot predict when cancer would onset due to the unknown proportion of cancers in each no-regression rate at each follow up time point. Moreover, similar estimates cannot be made for treated VaINs, as they are not comparable with the series reported by Sopracordevole et al. [10], Yu et al. [11], Kim et al. [12], and Gunderson et al. [13] reported above. Therefore, readers should be advised that treatments might reduce the number of cancer progression events, thereby increasing the number of cases of VaIN persistence or relapse. This behavior further explains why similar trends for treated and untreated VaIN patients have been observed in the present article.

A significant proportion of untreated VaINs (approximately 14% for both low-grade and high-grade VaINs) are unlikely to resolve over a 5-year follow up period, as shown in Figs. 2,3. These findings are consistent with the data reported by Aho et al. [9] (9% progression to cancer and 18% persistence over 3–15 years in untreated patients).

Moreover, a 3-year follow up period without colposcopic or cytologic abnormalities in the vagina following treatment does not guarantee the absence of VaIN recurrence later on. Therefore, it is recommended to gather more data on VaINs and conduct (even small) randomized trials to compare treatments and enhance the evidence base for VaIN management. Future studies should consider the specific characteristics of VaIN (grade, location, multifocality, previous hysterectomy, HPV types, and biomolecular risk markers) to tailor treatments effectively.

The natural history of both high-grade and low-grade VaINs tends towards spontaneous regression in 86% of cases within a 5-year observation period. It remains unclear to what extent treatments could improve this rate. Moreover, the authors are unable to determine the most effective approach for VaIN care because they are not able to assess the no regression rate trends for single treatment or for combined treatments, although laser excision and brachytherapy warrant further research attention. Current recommendation to individualize the treatment of VaINs [2] must be followed but primary VaIN follow up must extend beyond three years.

Datasets extracted by databases of authors’ institutions, as reported in the text, and trend shapes not reported in the draft, will be also provided on request contacting the corresponding author.

UI, CB, MMG, GS, EC and AF gave their significant intellectual contribution in reviewing, interpreting results. UI has planned the study, performed systematic research, attributed quality score (along with AF), extracted data (along with AF), made calculations, written the main version of the article; CB provided also her institutional database; GS provided also his institutional database; MMG collected also data from ASL 1 Umbria, cross linking the colposcopic database of ASL 1 Umbria with the pathological database on VaIN of ASL 1 Umbria, provided. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

As leader institution, the ASL 1 Umbria ethical board (Umbria Region Ethical Board-Italy) approved the study the 30 of February 2022, Prot. N. 24364/22/RI, CER Umbria Registry N. 4294/22. Given the retrospective collection of cases from institutional databases, consent to participate was waived.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Ugo Indraccolo and Alessandro Favilli are serving as the Editorial Board members of this journal. We declare that Ugo Indraccolo and Alessandro Favilli had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Tiziano Maggino.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/CEOG36377.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.