1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Xuzhou Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital Affiliated to Xuzhou Medical University, 221009 Xuzhou, Jiangsu, China

2 Center for Obstetrics and Gynecology, Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, Affiliated Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing University, 210093 Nanjing, Jiangsu, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Chromosomal abnormalities constitute the predominant genetic etiology of early pregnancy loss; however, conventional karyotyping analysis fails to detect submicroscopic genomic imbalances or regions of homozygosity (ROH). This retrospective cohort study utilizes chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) to systematically investigate chromosomal abnormalities associated with early pregnancy loss.

A cohort of 1006 specimens from products of conception (POCs) was collected and subjected to DNA extraction and CMA. Relevant clinical records were also reviewed.

Among the 1006 cases, CMA identified chromosomal abnormalities in a total of 596 cases (59.24%, 596/1006), including 529 cases (52.58%, 529/1006) with chromosomal numerical abnormalities, 58 cases (5.77%, 58/1006) with genomic imbalance, and 9 cases (0.89%, 9/1006) with ROH. The univariable analysis demonstrated that maternal age ≥35 years, paternal age ≥35 years, pregnancy loss at 8–9 weeks, and a history of live birth were significantly associated with an increased risk of numerical chromosomal abnormalities in pregnancy loss. A history of more than two pregnancy losses, pregnancy loss after 10 weeks, and conception via in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer (IVF-ET) were associated with a reduced risk of numerical chromosomal abnormalities. Multivariable regression analyses demonstrated that paternal age ≥35 years and history of live birth did not show a significant correlation. Euploid pregnancies with pathogenic or likely pathogenic copy number variations (CNVs) were not correlated with maternal or paternal age, pregnancy loss history, gestational age, IVF-ET conception, or live birth history.

Numerical chromosomal abnormalities are the leading cause of early pregnancy loss, demonstrating significant associations with maternal age, pregnancy loss history, and gestational age. Furthermore, pathogenic or likely pathogenic genomic imbalances may contribute to euploid pregnancy loss, although the incidence of CNVs does not correlate with clinical characteristics. The potential impact of ROH on pregnancy loss warrants further investigation.

Keywords

- chromosome microarray analysis

- copy number variations

- early pregnancy loss

- genomic imbalance

- regions of homozygosity

Early pregnancy loss is the most prevalent complication during the first trimester, with approximately 15.00%–25.00% of women of childbearing age experiencing at least one spontaneous abortion [1]. The etiology of pregnancy loss is multifaceted, encompassing a range of etiologies such as genetic abnormalities, uterine issues, endocrine dysfunction, thrombosis, immune disorders, lifestyle factors, and maternal infections [2]. Previous studies have shown that 50.00%–60.00% of pregnancy failures can be attributed to genetic abnormalities, mainly involving chromosome number abnormalities and genomic imbalances [3, 4]. Genetic analysis of products of conception (POCs) is the most effective means to identify the causes of pregnancy loss, alleviate the psychological burden, and help avoid unnecessary examinations and treatments. In addition, a precise diagnosis of genetic causes can guide couples in choosing the method of reproduction and prenatal diagnosis, avoiding recurrent miscarriages or giving birth to children with chromosomal diseases.

Chromosomal abnormalities in embryos that lead to early pregnancy loss include

abnormal chromosome numbers and segmental duplications/deletions; all belong to

the category of genome copy number variations (CNVs). Traditional cytogenetic

methods such as chromosome karyotyping analysis, however, cannot effectively

detect segmental abnormalities below 10 Mb, resulting in missed detections [5].

Alternative approaches, including quantitative fluorescent-polymerase chain

reaction (QF-PCR) and multiplex ligation-dependent probe amplification, have been

evaluated in genetic research. Still, their scope is limited to specific

detection targets [6, 7]. Chromosome microarray analysis (CMA), as the primary

method for CNVs detection, can detect chromosomal aneuploidy, imbalanced

structural rearrangements, submicroscopic copy number variations (

The presence of 2.20%–13.00% pathogenic copy number variants (pCNVs) in tissues with pregnancy loss suggests a potential relationship between pCNVs and euploid pregnancy loss [8]. A small number of studies have reported CNVs that may be associated with pregnancy loss, suggesting that genome imbalance caused by CNVs can affect gene dosage or disrupt chromosome segregation, leading to euploid pregnancy loss [9, 10, 11, 12]. However, the exact mechanisms by which CNVs lead to pregnancy loss remain incompletely understood. Meanwhile, with the widespread application of single nucleotide polymorphism microarray technology in genetics, the detection rate of ROH in pregnancy loss has been dramatically improved; whether ROH can increase the risk of early pregnancy loss remains to be studied. These uncertainties pose challenges for clinicians in interpreting the significance of CNVs or ROH detected in pregnancy loss.

This retrospective study analyzed the genetic etiology and influencing factors associated with pregnancy loss. In addition, it also attempts to investigate the correlation between genomic imbalance, ROH, and pregnancy loss, thereby providing better guidance for clinical counseling.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study of early pregnancy loss before 14 gestational weeks at the Obstetrics and Gynecology Medical Center of Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital, affiliated to Hospital of Medical School, Nanjing University. Our cohort encompassed women who sought treatment for pregnancy loss and wanted to seek a genetic etiology of their pregnancy loss by CMA between January 2018 and December 2021. Before undergoing testing, all of the couples signed informed consent forms for CMA detection procedures. Parental peripheral blood, along with the products of conceptions, were collected. Additionally, the age of the couples experiencing pregnancy loss, their history of pregnancy loss, gestational week, in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer (IVF-ET) pregnancy, and history of live birth were documented.

Genomic DNA from maternal peripheral blood and POCs were extracted using QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Cat NO: 51106, Qiagen, Hilden, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany) and QIAamp DNA Blood Mini Kit (Cat NO: 51304, Qiagen, Hilden, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany). According to the conventional operating procedure [13], CMA was performed using the Applied Biosystems™ CytoScan™ 750K Array (Cat NO: 901858, Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA). The Affymetrix Chromosome Analysis Suite version 4.0 software (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA, USA) was employed for analysis, referencing the 2019 American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics Standards and Guidelines for the Interpretation of Sequence Variables [14].

All patients with early pregnancy loss were categorized into two groups. We first divided all patients into normal embryonic chromosomal numerical (Group 1, 47.41%, 477/1006) and abnormal embryonic chromosomal numerical (Group 2, 52.58%, 529/1006) groups. We then divided patients with normal embryonic chromosomal numerical (Except for VOUS CNVs and ROH in Group 1) into pathogenic or likely pathogenic CNVs (CNVs group, 7.24%, 32/442) and without CNVs (Non-CNVs group, 92.76%, 410/442).

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS (Version 22.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Non-normal distributed data were described by median (min, max). Categorical data were expressed and presented as percentages (%), and logistic regression analyses were used to estimate the odds ratios (OR) and the 95% confidence intervals (CI) for categorical outcomes. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses explored (1) the association between chromosomal numerical abnormalities in pregnancy loss and clinical characteristics and (2) the association between pathogenic or likely pathogenic CNVs in euploid pregnancy loss and clinical characteristics.

We employed binary logistic regression to assess the associations between

independent variables and outcomes. Multicollinearity among predictors was

evaluated by calculating variance inflation factors through linear regression

models. Influential outliers were identified using studentized residuals. To

rigorously control for confounding effects, stratified analyses were conducted

across the following predefined covariates: maternal age (

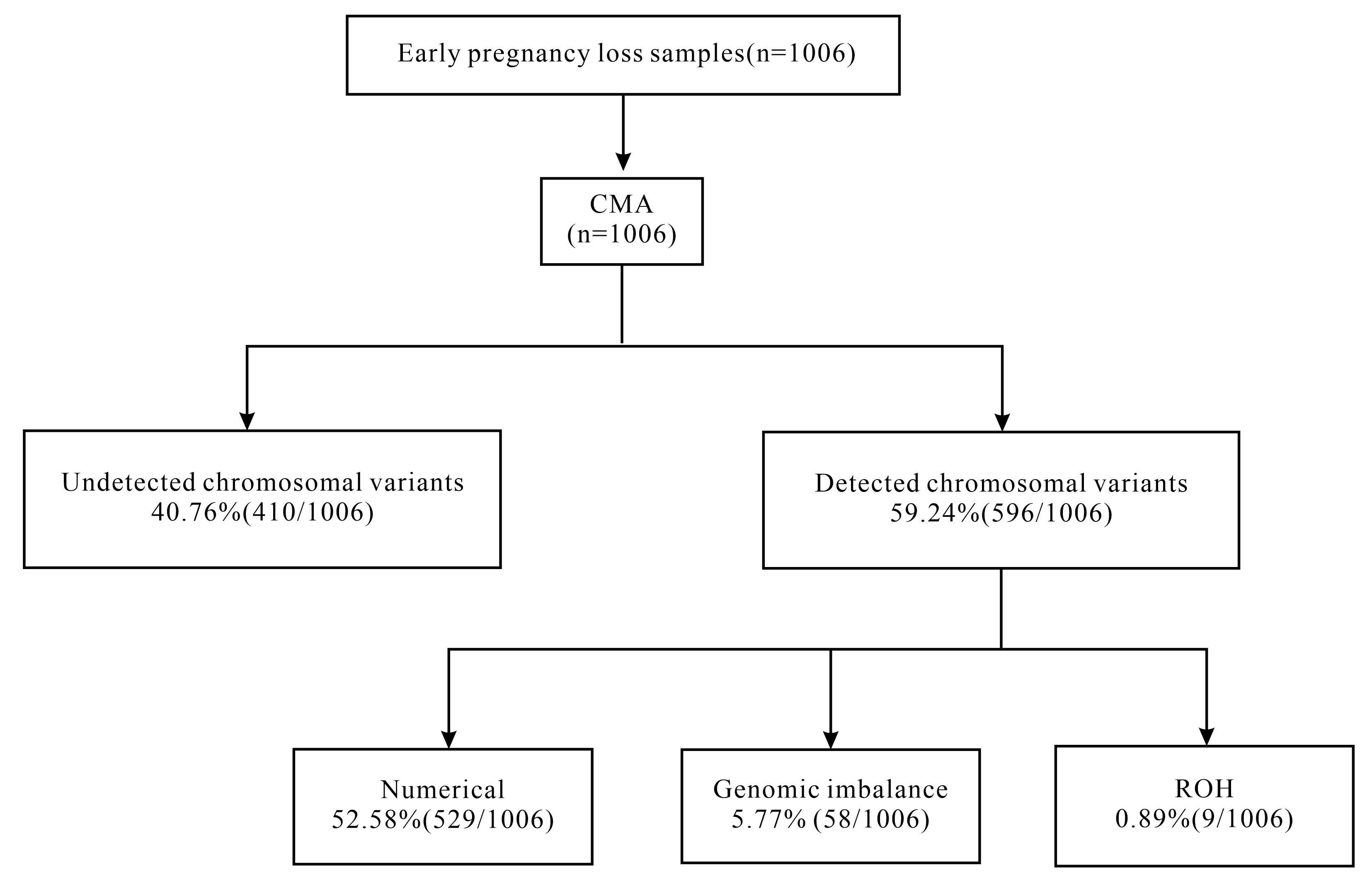

The cohort consisted of 1006 single pregnant women who had experienced pregnancy losses. All of them underwent successful CMA testing on POCs. The testing strategies for the genetic analysis of POCs are summarized in Fig. 1. The average maternal age was 31.62 (19, 47) years, and the average gestational week was 6.82 (5, 13) weeks. The average age of paternal was 32.77 (22, 57) years. The characteristics of the patients are shown in Table 1. CMA identified 59.24% (596/1006) cases with chromosomal abnormalities. Single chromosome trisomy was the most common abnormality, accounting for 37.67% (379/1006) of all the abnormalities, among which the most affected single chromosome trisomy were trisomy-16, trisomy-22 and trisomy-15, accounting for 30.61% (116/379), 16.89% (64/379) and 9.80% (37/379) respectively. About 5.77% (58/1006) cases carried genomic imbalance, including 32 pathogenic or likely pathogenic CNVs and 26 variants of uncertain significance (VOUS) CNVs. 0.89% (9/1006) cases showed ROH (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of the CMA of early pregnancy loss and the analytical strategies used in the present study. CMA, chromosomal microarray analysis; ROH, regions of homozygosity.

| Characteristics | Statistics (n = 1006) | Frequency (%) | |

| Maternal age | |||

| 764 | 75.94 | ||

| 242 | 24.06 | ||

| Paternal age | |||

| 696 | 69.18 | ||

| 310 | 30.82 | ||

| History of pregnancy loss | |||

| 1 | 618 | 61.43 | |

| 388 | 38.57 | ||

| Gestational week | |||

| 759 | 75.45 | ||

| 8–9 | 207 | 20.58 | |

| 40 | 3.98 | ||

| IVF-ET | |||

| YES | 482 | 47.91 | |

| NO | 524 | 52.09 | |

| Live birth history | |||

| YES | 120 | 11.93 | |

| NO | 886 | 88.07 | |

IVF-ET, in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer.

| Chromosomal abnormality | Statistics (n = 1006) | Frequency (%) | |

| Numerical abnormalities | 529 | 52.58 | |

| Trisomy | 408 | 40.56 | |

| Single chromosome trisomy | 379 | 37.67 | |

| Multiple chromosome trisomy | 29 | 2.88 | |

| Monosomy | 63 | 6.26 | |

| Autosomal monosomy | 5 | 0.50 | |

| Monosomy X | 58 | 5.77 | |

| Triploid* | 38 | 3.78 | |

| Mosaicisms | 20 | 1.99 | |

| Genomic imbalance | 58 | 5.77 | |

| pCNVs | 31 | 3.08 | |

| VOUS CNVs | 26 | 2.58 | |

| Likely pCNVs | 1 | 0.10 | |

| ROH | 9 | 0.89 | |

| Normal | 410 | 40.76 | |

pCNVs, pathogenic copy number variants; VOUS CNVs, variants of uncertain significance copy number variants; ROH, regions of homozygosity.

Those with triploid and aneuploid populations are included in the triploid count, while those with aneuploid and segmental deletions and/or duplications are included in the aneuploid count. *Including two cases of sub-triploid and three cases of super triploid.

Maternal age, paternal age, and live birth history demonstrated a significant association with increased risk factors for chromosomal numerical abnormalities and pregnancy loss (Table 3). Compared to loss before eight weeks, pregnancy loss at 8 to 9 weeks increases the risk of chromosomal numerical abnormalities (OR = 1.480, 95% CI: 1.082–2.024, p = 0.014). Conversely, pregnancy loss after ten weeks did not increase similar risk factors (OR = 0.512, 95% CI: 0.263–0.996, p = 0.049). Furthermore, IVF-ET pregnancies and a history of live births reduced the risk of chromosomal numerical abnormalities (OR = 0.698, 95% CI: 0.544–0.895, p = 0.005; OR = 1.651, 95% CI: 1.113–2.448, p = 0.013).

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | ||

| Maternal age | |||||||

| 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 2.191 | 1.618–2.966 | 2.504 | 1.685–3.721 | ||||

| Paternal age | |||||||

| 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 1.486 | 1.133–1.948 | 0.004 | 0.952 | 0.667–1.380 | 0.787 | ||

| History of pregnancy loss | |||||||

| 1 | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| 0.690 | 0.535–0.890 | 0.004 | 0.631 | 0.484–0.823 | 0.001 | ||

| Gestational week | |||||||

| 1.000 | 1.000 | ||||||

| 8–9 | 1.480 | 1.082–2.024 | 0.014 | 1.450 | 1.044–2.013 | 0.027 | |

| 0.512 | 0.263–0.996 | 0.049 | 0.457 | 0.229–0.910 | 0.026 | ||

| IVF-ET | |||||||

| NO | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| YES | 0.698 | 0.544–0.895 | 0.005 | 0.624 | 0.477–0.817 | 0.001 | |

| Live birth history | |||||||

| NO | 1.000 | 1.000 | |||||

| YES | 1.651 | 1.113–2.448 | 0.013 | 1.324 | 0.863–2.031 | 0.199 | |

IVF-ET, in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

After adjusting for confounding factors in multivariable backward stepwise regression analyses, we found no significant correlation between paternal age and history of live birth (OR = 0.952, 95% CI: 0.667–1.380, p = 0.787; OR = 1.324, 95% CI: 0.863–2.031, p = 0.199) (Table 3).

Overall, pathogenic or likely pathogenic CNVs were observed in 32 (3.18%)

cases, specifically with 21 duplications (21 pCNVs) and 32 deletions (31 pCNVs, 1

Likely pCNV) detected. These pathogenic or likely pathogenic CNVs ranged in size

from 221 kb to 102.5 Mb, and in 18 fetal tissues, two or more

deletions/duplications were identified. However, despite this variation, no

significant differences were found in clinical characteristics between euploid

pregnancy loss with and without pathogenic or likely pathogenic CNVs (all

p

| Characteristics | CNVs (n = 32) | Non-CNVs (n = 410) | Univariate analysis | |||

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

| Maternal age | ||||||

| 30 (93.75%) | 341 (83.17%) | 1.000 | ||||

| 2 (6.25%) | 69 (16.83%) | 0.329 | 0.077–1.041 | 0.135 | ||

| Paternal age | ||||||

| 25 (78.13%) | 301 (73.41%) | 1.000 | ||||

| 7 (21.88%) | 109 (26.59%) | 0.773 | 0.325–1.839 | 0.561 | ||

| History of pregnancy loss | ||||||

| 1 | 17 (53.13%) | 233 (56.83%) | 1.000 | |||

| 15 (46.88%) | 177 (43.17%) | 1.162 | 0.565–2.389 | 0.684 | ||

| Gestational week | ||||||

| 24 (75.00%) | 321 (78.29%) | 1.000 | ||||

| 8–9 | 6 (18.75%) | 67 (16.34%) | 1.198 | 0.471–3.043 | 0.704 | |

| 2 (6.25%) | 22 (5.37%) | 1.216 | 0.270–5.481 | 0.799 | ||

| IVF-ET | ||||||

| NO | 18 (56.25%) | 189 (46.10%) | 1.000 | |||

| YES | 14 (43.75%) | 221 (53.90%) | 0.665 | 0.322–1.373 | 0.270 | |

| Live birth history | ||||||

| NO | 31 (96.88%) | 374 (91.22%) | 1.000 | |||

| YES | 1 (3.13%) | 36 (8.78%) | 0.289 | 0.044–2.528 | 0.335 | |

CNVs: euploid pregnancy loss with pathogenic or likely pathogenic CNVs.

Non-CNVs: euploid pregnancy loss without CNVs.

Our data also shows that genomic imbalances are distributed across all

chromosomes except chromosomes 20 and 21. Among these, the most prevalent pCNVs

were detected on chromosome 8p, closely followed by chromosomes 21q and 6q.

Specifically, all CNVs identified on chromosome 21q were deletions. We identified

seven recurrent (n

Moreover, ROH was detected in 9 (0.89%) cases. Three of these cases exhibited whole-genome uniparental disomy (UPD). Two instances involved single chromosome UPD on chromosomes 8 and 21, possibly due to trisomy rescue, gamete complementation, or mitotic duplication. Additionally, four cases of ROH involving chromosomes 1p, 7q, 13q, and 13q may be linked to errors in meiosis of germ cells or mitosis of somatic cells.

This study utilized CMA technology to investigate the incidence and distribution of chromosomal abnormalities in 1006 cases of pregnancy loss tissues. Based on the findings, we determined that the incidence of chromosomal numerical abnormalities is correlated with maternal age, history of miscarriage, gestational week, and IVF-ET. In contrast, the incidence of CNVs is unrelated to clinical characteristics. Overall, the detection rate of chromosomal numerical abnormalities was 52.58% (529/1006), while the detection rate of genomic imbalance was 5.77% (58/1006). Furthermore, the detection rate for pathogenic or likely pathogenic CNVs was 3.20% (32/1006). The frequency of chromosomal numerical abnormalities aligns with findings from prior research [5, 9]. However, the detection rate of pathogenic or likely pathogenic CNVs (3.20%) is slightly lower than reported in previous studies [15, 16], which may be attributable to the varying gestational weeks included in the pregnancy loss study. In cases of euploid pregnancy loss, pathogenic or likely pathogenic CNVs account for approximately 7.20% (32/442, excluding VOUS and ROH). While these CNVs may contribute to pregnancy loss, their incidence does not correlate with clinical features. Consequently, non-chromosomal factors, such as maternal influences and monogenic variations, may play a more significant role in euploid pregnancy loss.

Notably, the most common CNVs observed in the pregnancy loss tissues was the 22q11.21 microdeletion, which can lead to DiGeorge syndrome characterized by cardiovascular malformations [17]. Furthermore, the incidence of 22q11.21 microdeletion in a cohort of 8184 healthy Asian individuals was zero [18]. This finding suggests a potential association between 22q11.21 microdeletion and embryonic lethality. Further research is needed to explore the role of the 22q11.21 microdeletion in miscarriage in the future.

Our research indicates that chromosomal numerical abnormalities (52.58%, 529/1006) represent the most significant proportion of chromosomal abnormalities associated with early pregnancy loss. Trisomy was identified as the most common chromosomal abnormality (40.56%), followed by monosomy (6.26%) and triploidy (3.78%). Most chromosomal aneuploidies often lead to embryonic lethality. Notably, single chromosome trisomy was commonly observed on chromosomes 16, 22, 15, 13, and 21, consistent with previous research [19]. Interestingly, no numerical abnormalities were detected on chromosomes 1 and 19, possibly related to their unique mechanisms during gamete meiosis [20]. Monosomy X, the most common type of chromosomal monomer variation, has been theorized to arise from sex chromosome loss post-zygosity, with paternal monosomy X embryos tending to miscarry earlier, potentially due to the distinct X chromosome imprinted gene expression patterns [21].

It is well-established that advanced maternal age is a significant risk factor for chromosomal numerical abnormalities in embryos. However, the relationship between advanced paternal age and chromosomal numerical abnormalities in embryos remains controversial. In 2020, a meta-analysis comprising nine studies indicated higher pregnancy loss rates in advanced paternal age, and the effect was less pronounced than in increased maternal age [17]. Punjani et al. [22] conducted a multivariable logistic regression analysis of 6704 couples undergoing fresh embryo transfer cycles. This revealed that increasing paternal age did not significantly impact embryo implantation, clinical intrauterine pregnancy, miscarriage, or live birth rates. Similarly, an analysis by Liao et al. [23], based on 56,113 frozen embryo transfer cycles, also suggested that paternal age may not adversely influence pregnancy and perinatal outcomes in assisted reproduction. This study reached comparable conclusions; univariate analysis revealed a significant correlation between advanced paternal age and abnormal embryonic chromosomal numerical abnormalities. However, this significance was not upheld in multiple regression analyses. This finding suggests that advanced paternal age alone may not pose an increased risk of pregnancy loss when considering pre-pregnancy counseling.

We also explored the association between gestational week and fetal chromosomal numerical abnormalities. Previous studies have linked earlier pregnancy loss to a higher incidence of chromosomal numerical abnormalities [18, 24]. Our findings indicate that pregnancy loss occurring between 8–9 weeks is more likely to exhibit chromosomal numerical abnormalities than those occurring before eight weeks, while pregnancy loss at or after ten weeks does not follow this pattern. The findings indicate that chromosomal numerical abnormalities are more likely to be eliminated during early pregnancy. The critical period of eight weeks in pregnancy is crucial for embryonic cardiovascular development, with severe cardiovascular defects resulting from chromosomal abnormalities often leading to pregnancy loss [25, 26, 27]. However, as pregnancy progresses, abnormal cells may become diluted and undetectable [28]. Additional studies with larger sample sizes and extended follow-up periods are necessary to support this hypothesis further.

Copy number variation sequencing (CNV-seq) is crucial in prenatal diagnosis, but the limitations on ROH detection restrict its application in the analysis of POCs [29]. Previous studies have reported that the frequency of ROH in cases of pregnancy loss ranges from 0.40% to 1.90% [4, 9, 10, 15]. In this study, the incidence of ROH in early pregnancy loss detected by CMA was found to be 0.89% (9/1006), which aligns with the findings in the existing literature. Among the nine ROH cases, three involved whole-genome UPD, resulting in early embryonic lethality, while two involved single chromosome UPD (involving chromosomes 8 and 21). Neither UPD (21) mat nor UPD (21) pat led to imprinting-related diseases. No disease-related imprinting genes have been identified for the remaining four ROH cases. Still, the loss of heterozygous signals may heighten the risk of homozygous pathogenic mutations in genes associated with the relevant regions. Our data indicates a low detection rate of ROH (0.89%) in early pregnancy loss, with no involvement of related imprinting-related diseases. Current literature lacks sufficient evidence to support ROH as a leading factor in pregnancy loss [30, 31]. CNV-seq is a more cost-effective alternative to CMA technology, requiring lower quality and quantity of DNA, offering higher throughput, and demonstrating greater sensitivity and specificity in detecting and quantifying chromosomal chimerism, a known cause of pregnancy loss [32]. Moreover, CNV-seq is widely accepted in clinical practice, making it a recommended approach for screening genetic causes of pregnancy loss despite a slight risk of missing ROH.

This study has certain limitations. Specifically, the small sample size and the focus solely on pregnancy loss from the current pregnancy restrict the findings. The accessibility of CMA testing could be limited by economic factors, potentially introducing selection bias in population sampling. Additionally, further studies are required on exon sequencing of euploid embryos to clarify the impact of single-gene variants on embryo development. Future research should prioritize larger sample sizes and systematic analysis of genetic factors linked to euploid pregnancy loss. This approach would facilitate an in-depth exploration of monogenic defects in euploid pregnancy loss, improving evidence for clinical management.

In conclusion, CMA provides valuable insights into the prevalence and distribution of chromosomal abnormalities in early pregnancy loss, with numerical chromosomal abnormalities representing the most common etiology. Moreover, pathogenic/likely pathogenic genomic imbalances may contribute to euploid pregnancy loss, whereas CNV incidence showed no association with clinical characteristics. The potential role of ROH in pregnancy loss requires further investigation. Our findings provide genetic evidence to inform clinical management of early pregnancy loss, supporting personalized strategies to reduce psychological distress in couples affected by pregnancy loss.

The data supporting this study’s findings are available upon reasonable request. The raw data and materials used in this research can be obtained from the corresponding author upon request.

HD drafted the manuscript and analyzed the data. JL and HLD designed the research study and supervised the study and revised the manuscript. XZ, WL and LG contributed to data management and interpreted data. CZ contributed to the conception of the study and data acquisition. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Nanjing Drum Tower Hospital affiliated to Nanjing University Medical School (No. 2021-464-02) and followed the Helsinki Declaration. All patients or their families gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study.

We would like to thank all the individuals and their families for participating and agreeing to donate their data.

The study was supported by funding for Clinical Trials from the Affiliated Drum Tower Hospital, Medical School of Nanjing University (2022-LCYJ-MS-06); The 14th Five-Year Plan Health Science and Education Capacity Improvement Project of Jiangsu Health Commision-Obstetrics and Gynecology Innovation Center (CXZX202229); Special Fund for Health Science and Technology Development of Nanjing City (YKK21096).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.