1 The First Clinical Medical College, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, 510405 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

2 Department of Gynaecology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, 510405 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Abstract

Tubal pregnancy, the most common ectopic type, requires urgent intervention. While medical therapy preserves fertility, diagnostic curettage (D&C) is often used if imaging is inconclusive. While medical therapy preserves fertility, D&C is often used if imaging is inconclusive.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted to analyze the clinical data of patients with tubal pregnancies who were hospitalized at the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine, from 2017 to 2021. Univariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression were used to adjust for confounding factors. A subgroup analysis stratified by human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level was also performed to investigate the impact of D&C on treatment outcomes.

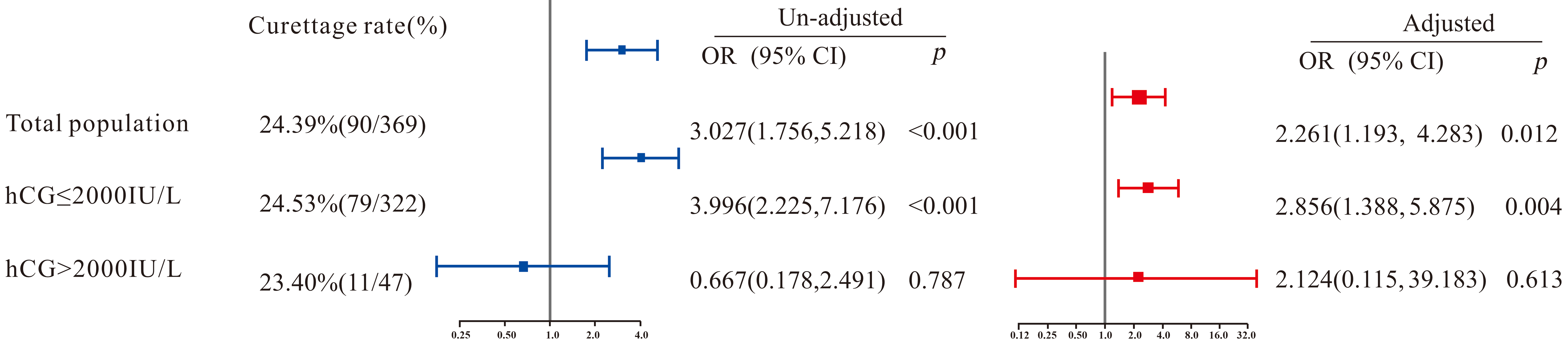

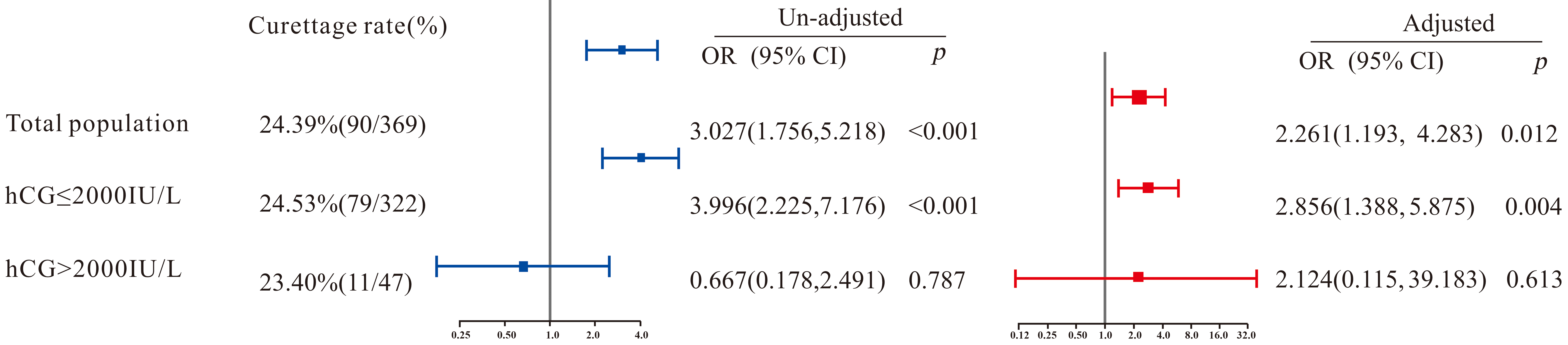

The overall failure rate of medical treatment was 24.39% (90/369), with 40.00% (36/90) in the curettage group and 19.35% (54/279) in the control group, showing a significant difference (p < 0.001). After adjusting for confounding factors, logistic regression indicated that the curettage group had a significantly higher failure rate of medical treatment compared to the control group (p = 0.012), with an adjusted odds ratio (OR) of 2.261 (95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.193–4.283). In other words, patients with tubal pregnancy who underwent curettage had a 2.261-fold higher risk of treatment failure compared to those who did not. In subgroup analysis, among patients with serum hCG ≤2000 IU/L, the curettage group had a significantly higher treatment failure rate than the control group (adjusted OR [95% CI] = 2.856 [1.388–5.875], p = 0.004). However, no significant difference was observed among patients with serum hCG >2000 IU/L (p > 0.05).

D&C may increase the risk of medical treatment failure in patients with tubal pregnancy and serum hCG levels ≤2000 IU/L.

Keywords

- diagnostic curettage

- tubal pregnancy

- medical treatment outcome

Ectopic pregnancy is defined as an abnormal pregnancy in which the fertilized

ovum implants outside the uterine cavity. Among all ectopic pregnancies, tubal

pregnancy (TP) is the most common, accounting for over 90%. When tubal pregnancy

is complicated by rupture and hemorrhage, it can lead to hemorrhagic shock and

potentially fatal outcomes, making prompt intervention critical. Medical therapy

is a conservative treatment option for tubal pregnancy, offering advantages of

being non-invasiveness, reduced pelvic adhesions, and preservation of the

affected fallopian tube [1, 2]. The expanding role of medical treatment is partly

due to improvements in early recognition and diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy.

Diagnostic curettage (D&C) is frequently employed as a supplemental diagnostic

tool for early ectopic pregnancy. Although ultrasound can diagnose the majority

of ectopic pregnancies, D&C remains particularly valuable when imaging results

are inconclusive. By examining uterine contents obtained via D&C, clinicians can

distinguish ectopic pregnancy from intrauterine pregnancy, thus avoiding

misdiagnosis and inappropriate use of medications such as methotrexate [3].

However, despite its diagnostic utility, the invasive nature of D&C raises

concerns about its potential interference with efficacy of medical treatment.

Early medical treatment for tubal pregnancy offers several advantages, including

preservation of the affected fallopian tube, reduction of pelvic adhesions,

avoidance of surgical trauma, and decreased treatment costs. This approach also

optimizes the pelvic environment and helps maintain future fertility for patients

who wish to conceive again [1, 2]. Although integrated traditional Chinese

and Western medicine has proven effective in appropriately selected patients

[4, 5], some tubal pregnancy patients still fail to respond to medical therapy

and require surgical intervention. Therefore, early assessment of the condition

and avoidance of high-risk factors are critically important in the medical

management of tubal pregnancy. Diagnostic curettage is widely used as an adjunct

tool to distinguish early pregnancies of unknown location. By analyzing

pathological findings from endometrial tissue and post-procedure changes in

specific serum beta human chorionic gonadotropin (

In this study, we focused on patients with tubal pregnancy who met the pharmacological treatment criteria described in the Guidelines for Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Diagnosis and Treatment of Tubal Pregnancy [6], using treatment outcomes as the primary measure. The objective was to elucidate the impact of D&C on the medical management of tubal pregnancy and provide clinical guidance for optimizing therapeutic strategies.

A retrospective cohort study was conducted on patients with tubal pregnancy who received integrated traditional Chinese and Western medicine in the gynecology ward of the First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine from January 2017 to December 2021. Clinical data were retrieved from the hospital’s medical record system. Patients were divided into a curettage group (drug treatment plan with diagnostic curettage) and a control group (drug treatment without diagnostic curettage) based on whether they underwent diagnostic curettage during hospitalization. All included patients gave informed consent for the treatment plan and signed the informed consent form for drug treatment of tubal pregnancy. This study was approved by the hospital ethics committee (ethical approval number: JY [2021] 099).

(1) Women aged 18–45 years, diagnosed with ectopic pregnancy and showing an adnexal mass on color Doppler ultrasound.

(2) Met the criteria for drug therapy specified in the Guidelines for the

Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine Diagnosis and Treatment of

Tubal Pregnancy, including stable vital signs, no signs of tubal rupture, absence

of active bleeding,

(3) Had a definitive treatment outcome.

(1) Pathology confirming ovarian, interstitial or other non-tubal pregnancy.

(2)

(3) Concomitant abnormal liver or kidney function; endocrine disorders such as thyroid disease or diabetes; hematologic disorders; infectious diseases; or malignancies.

(4) Missing critical indicators or data.

(5) Did not meet surgical indications during therapy, but opted to terminate drug treatment for personal reasons and underwent surgery.

(6) Did not meet the discharge criteria yet requested discharge, or failed to

follow up on

The indications for drug therapy were based on clinical guidelines [6].

(a) Previously positive

| 1 point | 2 point | 3 point | |

| Gestational weeks | |||

| Abnormal pain | Painless | Dull pain | Acute pain |

| 1000–3000 IU/L | |||

| Maximum diameter of pelvic hemorrhage (Ultrasonic diagnosis) | 3–6 cm | ||

| Maximum diameter of tubal pregnancy mass (Ultrasonic diagnosis) | 3–5 cm |

After adding each item’ scores according to the actual situation of the patient, the total score is obtained.

(b) For cases with

(1) Unruptured stage (no rupture or miscarriage): score

(2) Ruptured stage (tubal rupture or miscarriage): score

Under these conditions, patients are eligible for drug therapy:

(1) For

(2) For an unruptured-stage score of 9–10 points, or a score

2.2.2.1 Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

According to the tubal pregnancy factor scoring model, blood

2.2.2.2 Western Medicine

Single, double, or multi-dose regimens of methotrexate (MTX; Zhejiang Hai Zheng Pharmaceutical Co.; H20055198; Taizhou, Zhejiang, China. Mode of administration of the drug: intramuscular injection, 50 mg/m2), and mifepristone (Zhejiang Xianju Pharmaceutical Sales Co., Ltd.; H10950347; Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China. Mode of administration of the drug: Oral) alone or in combination with MTX.

2.2.3.1 Cured Group

Patients were classified as “Cured” if their blood

2.2.3.2 Accepted Surgery Group

Patients were classified as “Accepted surgery” if they met any of the

following criteria for treatment failure: (1) rising

Based on previous studies examining factors influencing ectopic pregnancy drug treatment outcomes [9, 10] and tubal pregnancy rupture [11, 12, 13, 14], potential confounding variables included:

(1) Pregnancy Variables: Duration of amenorrhea, gestational weeks, pretreatment

blood

(2) Clinical Symptoms: Abdominal pain, presence or absence of vaginal bleeding.

(3) Medical History: Previous ectopic pregnancy, number of abortions, history of tubal surgery.

(4) Ultrasound Findings: Location of the tubal pregnancy, extent of pelvic effusion, diameter of the pregnancy mass, and endometrial thickness.

(5) Drug Treatment Regimen: Type of pharmacological therapy received.

All statistical analyses were performed using the EmpowerStats software

(http://www.empowerstats.com, X&YSolutions, Inc., Boston, MA, USA) based on the

R language. First, univariate analysis was conducted to identify potential

confounding factors influencing treatment outcome. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test

(SPSS 25.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to assess the normality of

continuous data. For non-normally distributed variables, the median (lower

quartile, upper quartile) was used for description, and the Mann-Whitney U test

was used for comparison between groups. Categorical data were expressed as

frequency (percentage) and compared using the Pearson chi-square test.

Subsequently, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to adjust

for confounding factors and assess the impact of diagnostic curettage on tubal

pregnancy treatment outcomes. A significance level of p

A total of 369 eligible patients were included in this study and categorized

into two mutually exclusive outcome groups based on predefined criteria (see

Section 2.2.3). Cured group (n = 279): Patients who achieved successful medical

treatment outcomes (

During the same period, only 8 patients suspected of ectopic pregnancy were

ultimately diagnosed with intrauterine pregnancy via diagnostic curettage (these

cases were excluded from the study). In addition, there were also statistically

significant differences between the curettage and control groups in terms of

vaginal bleeding symptoms, blood hCG levels, the “hCG value/days of amenorrhea”

ratio, progesterone levels, endometrial thickness, and treatment regimen (all

p

| Factors | Control group (n = 279) | D&C group (n = 90) | Z/ |

p value | |

| Duration of amenorrhea (days) | 47 (40, 54) | 45 (41, 52) | –0.864 | 0.387 | |

| Duration of amenorrhea (weeks) | - | - | 3.147 | 0.207 | |

| 76 (27.24%) | 25 (27.78%) | - | - | ||

| 6–8 | 150 (53.76%) | 55 (61.11%) | - | - | |

| 53 (19.00%) | 10 (11.11%) | - | - | ||

| Age (year) | 30 (26, 33) | 31 (27, 36) | 1.626 | 0.104 | |

| Pregnant position | - | - | 0.026 | 0.873 | |

| Left fallopian tube | 136 (48.75%) | 43 (47.78%) | - | - | |

| Right fallopian tube | 143 (51.25%) | 47 (52.22%) | - | - | |

| Abdominal pain | - | - | 0.397 | 0.820 | |

| Painless | 87 (31.18%) | 31 (34.44%) | - | - | |

| Dull pain | 107 (38.35%) | 34 (37.78%) | - | - | |

| Acute pain | 85 (30.47%) | 25 (27.78%) | - | - | |

| Vaginal bleeding | - | - | 7.918 | 0.005 | |

| No | 17 (6.09%) | 14 (15.56%) | - | - | |

| Yes | 262 (93.91%) | 76 (84.44%) | - | - | |

| No. of artificial abortion | - | - | 1.409 | 0.235 | |

| 0–1 | 207 (74.19%) | 61 (67.78%) | - | - | |

| 72 (25.81%) | 29 (32.22%) | - | - | ||

| History of ectopic pregnancy | - | - | 0.198 | 0.656 | |

| No | 232 (83.15%) | 73 (81.11%) | - | - | |

| Yes | 47 (16.85%) | 17 (18.89%) | - | - | |

| Previous tubal surgery | - | - | 0.043 | 0.835 | |

| No | 233 (83.51%) | 76 (84.44%) | - | - | |

| Yes | 46 (16.49%) | 14 (15.56%) | - | - | |

| Serum |

383.9 (160.2, 1034.0) | 1545.5 (767.6, 2154.9) | 3.599 | ||

| The ratio of serum hCG level to days of amenorrhea (IU/L/d) | 7.91 (3.29, 21.33) | 14.55 (8.11, 29.69) | 3.676 | ||

| Progesterone levels (nmol/L) | 11.38 (4.79, 22.94) | 19.19 (10.71, 39.58) | 4.639 | ||

| Diameter of gestational mass | - | - | 4.737 | 0.094 | |

| 170 (60.93%) | 66 (73.33%) | - | - | ||

| 3–5 cm | 95 (34.05%) | 20 (22.22%) | - | - | |

| 14 (5.02%) | 4 (4.44%) | - | - | ||

| Range of pelvic effusion | - | - | 0.287 | 0.962 | |

| 0 cm | 125 (44.80%) | 42 (46.67%) | - | - | |

| 43 (15.41%) | 12 (13.33%) | - | - | ||

| 3–6 cm | 91 (32.62%) | 29 (32.22%) | - | - | |

| 20 (7.17%) | 7 (7.78%) | - | - | ||

| Endometrial thickness (mm) | 8.0 (5.4, 11.0) | 11.0 (8.0, 15.0) | 5.644 | ||

| Medical management | - | - | 10.055 | 0.007 | |

| TCM treatment | 162 (58.06%) | 35 (38.89%) | - | - | |

| TCM and western medicine treatment | 83 (29.75%) | 39 (43.33%) | - | - | |

| Western medicine was added after TCM treatment | 34 (12.19%) | 16 (17.78%) | - | - | |

| Treatment outcome | - | - | 15.728 | ||

| Cured | 225 (80.65%) | 54 (60.00%) | - | - | |

| Accepted surgical operation | 54 (19.35%) | 36 (40.00%) | - | - | |

Notes: Cured group (n = 279): Patients with successful medical treatment

(

Through univariate analysis to explore the impact of various indicators on the

drug treatment outcome, the results demonstrated that the days of amenorrhea,

weeks of amenorrhea, number of abortions, history of ectopic pregnancy, history

of tubal surgery, blood hCG value, “blood hCG value/days of amenorrhea” ratio,

progesterone value, diameter of the pregnancy mass, endometrial thickness, drug

treatment plan, and diagnostic curettage operation were related to the drug

treatment outcome, with statistically significant differences (p

| Factors | Medical treatment outcomes | ||||

| Cured (n = 279) | Accepted surgery (n = 90) | OR (95% CI) | p value* | ||

| Duration of amenorrhea (days) | 47 (42, 54) | 44 (40, 50) | 0.98 (0.96, 1.00) | ||

| Duration of amenorrhea (weeks) | - | - | - | 0.026 | |

| 68 (24.37%) | 33 (36.67%) | 1.00 | - | ||

| 6–8 | 157 (56.27%) | 48 (53.33%) | 0.63 (0.37, 1.07) | 0.086 | |

| 54 (19.35%) | 9 (10.00%) | 0.34 (0.15, 0.78) | 0.011 | ||

| Pregnant position | - | - | - | - | |

| Left fallopian tube | 131 (46.95%) | 48 (53.33%) | 1.00 | - | |

| Right fallopian tube | 148 (53.05%) | 42 (46.67%) | 0.77 (0.48, 1.25) | 0.352 | |

| Abdominal pain | - | - | - | 0.825 | |

| Painless | 91 (32.62%) | 27 (30.00%) | 1.00 | - | |

| Dull pain | 107 (38.35%) | 34 (37.78%) | 1.07 (0.60, 1.91) | 0.816 | |

| Acute pain | 81 (29.03%) | 29 (32.22%) | 1.21 (0.66, 2.21) | 0.542 | |

| Vaginal bleeding | - | - | - | - | |

| No | 23 (8.24%) | 8 (8.89%) | 1.00 | - | |

| Yes | 256 (91.76%) | 82 (91.11%) | 0.92 (0.40, 2.14) | 1.000 | |

| No. of artificial abortion | - | - | - | - | |

| 0–1 | 215 (77.06%) | 53 (58.89%) | 1.00 | - | |

| 64 (22.94%) | 37 (41.11%) | 2.35 (1.42, 3.88) | 0.001 | ||

| History of ectopic pregnancy | - | - | - | - | |

| No | 238 (85.30%) | 67 (74.44%) | 1.00 | - | |

| Yes | 41 (14.70%) | 23 (25.56%) | 1.99 (1.12, 3.55) | 0.027 | |

| Previous tubal surgery | - | - | - | - | |

| No | 243 (87.10%) | 66 (73.33%) | 1.00 | - | |

| Yes | 36 (12.90%) | 24 (26.67%) | 2.45 (1.37, 4.40) | 0.004 | |

| Serum |

373.0 (149.6, 800.5) | 1264.0 (438.4, 2484.0) | 1.00 (1.00, 1.00) | ||

| The ratio of serum hCG level to days of amenorrhea (IU/L/d) | 7.89 (3.24, 16.86) | 30.17 (9.00, 54.58) | 1.03 (1.02, 1.05) | ||

| Progesterone levels (nmol/L) | 11.30 (4.87, 22.00) | 22.31 (11.16, 37.87) | 1.02 (1.01, 1.03) | ||

| Diameter of gestational mass | - | - | - | 0.007 | |

| 166 (59.50%) | 70 (77.78%) | 1.00 | - | ||

| 3–5 cm | 97 (34.77%) | 18 (20.00%) | 0.44 (0.25, 0.78) | 0.005 | |

| 16 (5.73%) | 2 (2.22%) | 0.30 (0.07, 1.32) | 0.111 | ||

| Range of pelvic effusion | - | - | - | 0.875 | |

| 0 cm | 124 (44.44%) | 43 (47.78%) | 1.00 | - | |

| 42 (15.05%) | 13 (14.44%) | 0.89 (0.44, 1.82) | 0.754 | ||

| 3–6 cm | 91 (32.62%) | 29 (32.22%) | 0.92 (0.53, 1.58) | 0.761 | |

| 22 (7.89%) | 5 (5.56%) | 0.66 (0.23, 1.84) | 0.422 | ||

| Endometrial thickness (mm) | 8.0 (6.0, 12.0) | 10.0 (6.63, 13.0) | 1.08 (1.03, 1.13) | ||

| Medical management | - | - | - | ||

| TCM treatment | 170 (60.93%) | 27 (30.00%) | 1.00 | - | |

| TCM and western medicine treatment | 68 (24.37%) | 54 (60.00%) | 5.00 (2.91, 8.59) | ||

| Western medicine was added after TCM treatment | 41 (14.70%) | 9 (10.00%) | 1.38 (0.60, 3.16) | 0.444 | |

| Diagnostic curettage | - | - | - | - | |

| No | 225 (80.65%) | 54 (60.00%) | 1.00 | - | |

| Yes | 54 (19.35%) | 36 (40.00%) | 2.78 (1.66, 4.65) | 0.001 | |

Notes: OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval. Cured group: Patients with

successful medical treatment (

To further evaluate the effect of diagnostic curettage on the outcome of drug

therapy for tubal pregnancy, we performed multivariate logistic regression after

adjusting for the confounding factors previously identified. In addition, given

the substantial influence of blood hCG levels on treatment outcomes, a subgroup

analysis was conducted using 2000 IU/L as the cutoff. The results are presented

in Fig. 1. Overall, a significant difference in treatment outcomes was observed

between the curettage group and the control group (p = 0.012), with an

OR (95% CI) of 2.261 (1.193–4.283), indicating that the failure probability of

tubal pregnancy patients who underwent curettage during treatment was 2.261 times

(1.193, 4.283) that of those who did not. In the subgroup with blood

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Multivariate logistic regression on the correlation between diagnostic curettage and medical treatment outcome. OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin.

This study evaluated the impact of diagnostic curettage on the outcomes of

medical treatment for tubal pregnancy in a cohort of 369 patients. We found that

patients who underwent diagnostic curettage had a significantly higher rate of

treatment failure compared to those who did not. After adjusting for relevant

confounding factors, diagnostic curettage was associated with a more than twofold

increase in the odds of treatment failure. Notably, in the subgroup of patients

with

Previous studies have not definitively clarified whether diagnostic curettage

influences the outcomes of medical therapy in tubal pregnancy. However, this

5-year retrospective cohort study indicates that, even after controlling for

factors such as blood

Recognizing the significant role of blood

Consequently, clinicians should avoid diagnostic curettage whenever possible in

patients with

The diagnostic curettage operation process includes intravenous anesthesia, curettage operation, and postoperative anti-infection treatment. The use of anesthetic and broad-spectrum antibiotics may inhibit the intestinal flora and affect liver and kidney function to some extent, thereby affecting the absorption and metabolism of drugs and weakening the therapeutic effect of drugs on early tubal pregnancy.

In addition, the curettage operation removes the thick functional layer of the endometrium, which is rich in estrogen and progesterone receptors. This may reduce the local estrogen and progesterone receptors in the endometrium, thereby affecting the regulatory mechanism of estrogen and progesterone and further affecting the progress of early tubal pregnancy.

From the perspective of traditional Chinese medicine, uterine cavity operation damages the blood vessels of the uterus to some extent, causing some blood to overflow outside the vessels. The blood that leaves the meridians is transformed into blood stasis, blocking the uterine vessels and causing qi stagnation in the uterus and Chong and Ren meridians. In addition, there is a deficiency of essence and blood. The kidney governs the uterus and stores essence, and the kidney essence and qi are indirectly damaged, resulting in failure to store essence and the fetus is not restrained, leading to disease progression.

Although the mechanisms remain speculative, the findings of this study warrant

clinical attention. Because this was a single-center, retrospective study with a

relatively modest sample size, further research in multi-center settings with

larger sample sizes is recommended. A future prospective, randomized controlled

trial could provide more definitive evidence on whether diagnostic curettage

affects the outcomes of drug therapy for tubal pregnancy. Considering

comprehensively the auxiliary diagnostic value of diagnostic curettage for tubal

pregnancy and its impact on drug treatment, for suspected tubal pregnancy

patients with a blood

In conclusion, our findings indicated that diagnostic curettage may increase the

likelihood of medical treatment failure in tubal pregnancy, particularly when

blood

The authors serve as custodians of the anonymized data, which may be made available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

LY and XW performed the research. JQ and CZ provided help and advice on acquisition of data, LY and XW analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. The protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine (ethical approval number: JY [2021] 099). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their legal guardians prior to their inclusion in the study.

We convey our sincere thanks to the staff of the First Clinical Medical College, Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine and the Department of Gynaecology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine for their support throughout this work.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.