1 Shahid Beheshti Fertility Center, Department of Anatomy and Reproductive Biology, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, 8715988141, Isfahan, Iran

2 Shahid Beheshti Fertility Center, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, 8715988141, Isfahan, Iran

3 School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, 8715988141 Isfahan, Iran

4 Department of Pathology, School of Medicine, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, 8715988141, Isfahan, Iran

5 Fertility and Infertility Research Center, Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences, 7916613885, Bandar Abbas, Iran

Abstract

Endometriosis, a common cause of infertility, adversely impacts both the quality and quantity of oocytes and embryos, with increasing severity negatively influencing assisted reproductive technology (ART) outcomes. This study aims to elucidate and compare the efficacy of two fertilization methods: conventional in vitro fertilization (IVF) following short in vitro maturation (IVM) versus intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) in patients with varying stages of endometriosis.

In this retrospective study, a total of 134 infertile patients with endometriosis undergoing IVF-ICSI treatment were included. The patients were classified into two groups based on the stage of endometriosis: Stage I–II (n = 79, Group 1) and stage III–IV (n = 55, Group 2). Within each group, participants underwent ART treatments in which sibling oocytes were randomly assigned to either conventional IVF following a short IVM period or the ICSI group. The primary outcomes—fertilization rate, embryo formation rate, and the proportion of high-quality embryos—were assessed and compared between subgroups using the Mann-Whitney U test.

Among patients with stage I–II endometriosis, no significant differences were observed between the IVF following short IVM and ICSI subgroups regarding fertilization rate (70 vs. 73, p = 0.543), embryo formation rate (86 vs. 90, p = 0.444), or high-quality embryo rate (67 vs. 71, p = 0.570). Similarly, in the stage III–IV endometriosis group, fertilization rate, embryo formation rate, and the proportion of top-quality embryos on day 3 did not differ significantly between the two subgroups (p > 0.05).

Our findings indicated that conventional IVF following a short IVM period yielded comparable outcomes to ICSI in patients with varying stages of endometriosis. Therefore, conventional IVF following a short IVM period may be considered an effective and less invasive fertilization approach for the management of endometriosis-associated infertility.

Keywords

- fertilization rate

- oocyte

- embryo development

- high-quality embryo

Endometriosis is an estrogen-dependent, chronic, and often painful gynecological disorder characterized by the presence of endometrial-like tissue outside the uterine cavity [1]. It affects 10–15% of females of reproductive age and is known to have a detrimental impact on fertility [2, 3].

The underlying causes of infertility in endometriosis remain elusive, despite various proposed mechanisms [4]. One plausible way in which endometriosis impairs fertility and compromises the chances of achieving a successful pregnancy is by adversely affecting the quality and quantity of oocytes and embryos [5]. While in vitro fertilization (IVF) is a recognized and effective treatment option for endometriosis-related infertility [6], several studies have shown that individuals experiencing endometriosis-associated infertility undergoing IVF treatments exhibit a significant decline in the total number of oocytes, the number of mature oocytes, and the levels of nuclear and cytoplasmic oocyte maturation. Additionally, they experience reduced rates of fertilization, implantation, and clinical pregnancy [7, 8, 9, 10].

Some studies suggest that the severity of endometriosis can significantly affect the success of IVF treatments [11, 12]. A notable decrease in fertilization rates has been observed in the advanced stages (stages III and IV) of endometriosis compared to the milder stages (stages I and II) [13]. Pellicer and colleagues found that women with stage III–IV endometriosis had fewer blastomeres per embryo and a higher frequency of embryos arrested in development [12]. However, other studies have failed to identify any significant effects on indicators of reproductive success [14, 15].

Notably, peritoneal fluid from women with endometriosis has been found to inhibit the binding of spermatozoa to the zona pellucida [16]. In light of these challenges, it has been suggested that intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), originally developed for severe male factor infertility, could be applied to non-male factor infertile patients, including those with previous complete fertilization failure or low fertilization rates in conventional IVF cycles. Split insemination of oocytes using both IVF and ICSI has been recommended for patients with unexplained infertility undergoing IVF treatment, as a strategy to mitigate the risk of fertilization failure after IVF [17].

Given the lack of clear evidence on the optimal fertilization method for patients with different stages of endometriosis, this study compared the outcomes of conventional IVF after short in vitro maturation (IVM) and ICSI, focusing on fertilization rates, embryo quality, and development to provide more insightful comparisons.

This retrospective study was conducted on infertile patients with endometriosis who underwent IVF-ICSI treatment at Zeinabieh IVF Center and Shahid Beheshti Hospital from July 2021 to August 2022. The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (IR.MUI.MED.REC.1402.313).

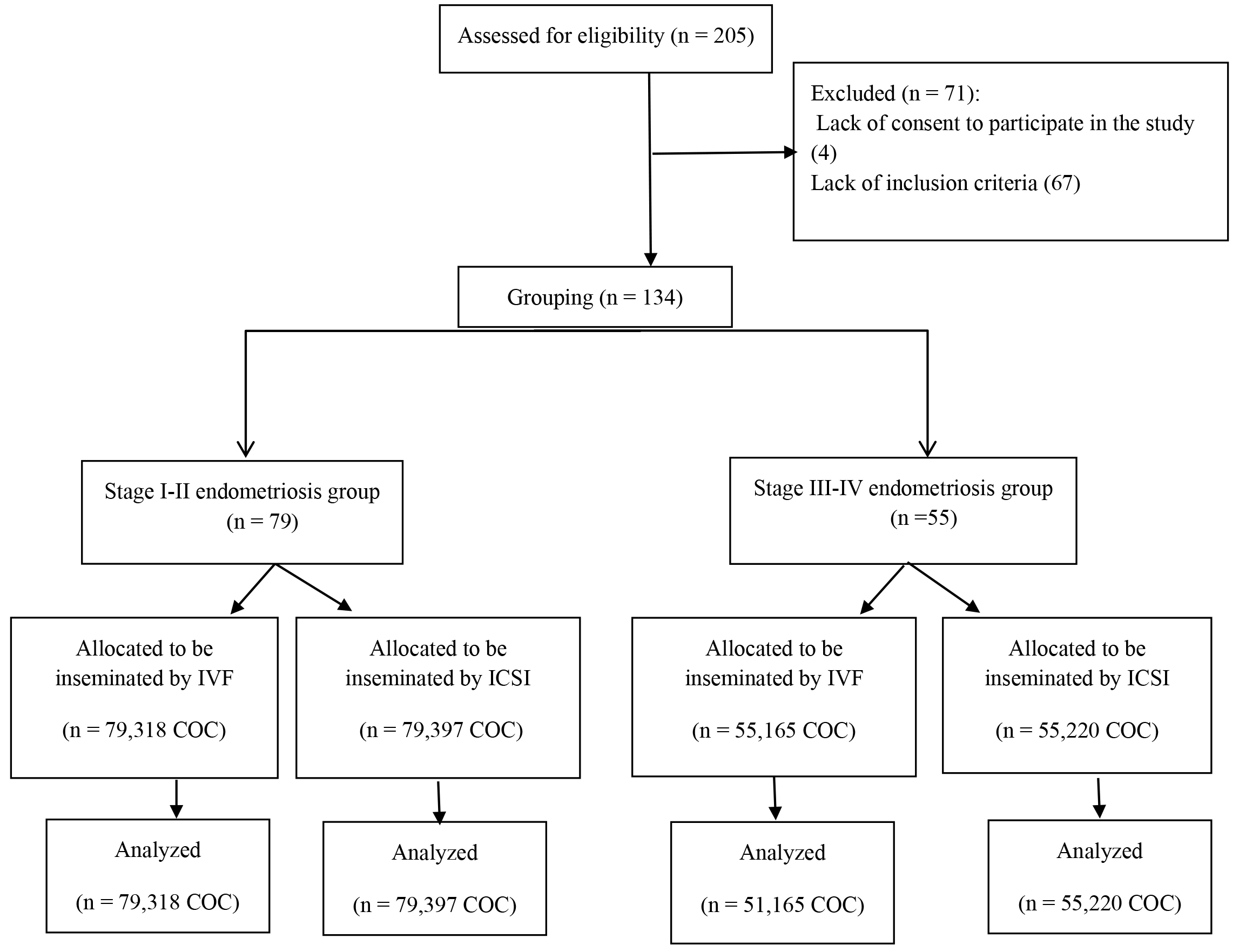

A total of 205 infertile patients with endometriosis, aged 18–39 years, undergoing IVF-ICSI treatment were initially recruited for the study. After screening, 71 women were excluded due to ineligibility, resulting in 134 patients being divided into two study groups. The first group consisted of 79 patients with stage I–II endometriosis, while the second group included 55 patients with stage III–IV endometriosis. Within each group, patients underwent assisted reproductive technology (ART) treatment, either through the insemination of sibling oocytes using IVF following short IVM or ICSI, utilizing normozoospermic samples. The exclusion criteria for the collected cases were: (i) age

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Flow diagram of patient inclusion and group allocation. IVF, in vitro fertilization; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; COC, cumulus-oocyte-complex.

The diagnosis of endometriosis was confirmed surgically and verified through histopathological examination. Endometriosis was graded according to the American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) staging system, which classifies the disease into four stages: minimal (stage I), mild (stage II), moderate (stage III), and severe (stage IV). These stages are determined based on factors such as the size, location, and depth of endometriotic lesions, as well as the presence of adhesions and the extent of organ involvement. Stages I and II represent milder forms of the disease, characterized by fewer and smaller lesions. In contrast, stages III and IV are more severe, involving extensive tissue involvement and a higher likelihood of significant scarring and adhesions.

All participants underwent a standardized ovulation induction regimen. They received six doses of recombinant FSH (r-hFSH; Gonal-F) (44087-9005-6, Merck Serono, Darmstadt, Germany) at 150 IU/day via subcutaneous injection, starting on the second day of their menstrual cycle. Additionally, intramuscular human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG; Menogon, Ferring Pharmaceuticals A/S, Copenhagen, Denmark) was administered at 75 IU/day from the fourth day of their menstrual cycle until the day of ovulation trigger.

Transvaginal sonography was initiated on day 7 of the menstrual cycle and repeated every other day. Cetrotide (Merck Serono) was administered subcutaneously at 250 µg/day upon detection of at least three mature follicles (

If more than three mature follicles (

For our procedures, we employed a SAGE1-Step culture medium (CooperSurgical, Måløv, Denmark), supplemented with human serum albumin from the same manufacturer. After oocyte retrieval, the COCs were randomly allocated to either the ICSI or conventional IVF groups. In the ICSI group, cumulus cells were removed, and only metaphase II (MII) oocytes were selected for injection. In the conventional insemination group, the COCs underwent a pre-incubation period of 3 hours in IVM media (SAGE-In Vitro Maturation Medium, CooperSurgical) prior to insemination, to enhance both cytoplasmic and nuclear maturation. Subsequently, oocytes were partially denuded prior to insemination to verify their maturation status. Immature oocytes (those at the germinal vesicle (GV) and metaphase I (MI) stages) were excluded from the study.

The semen sample collected on the day of oocyte retrieval was confirmed to be within normal parameters. Sperm were processed using the swim-up technique and inseminated at a concentration of 100,000 motile sperm per milliliter. In the ICSI group, cumulus cells were removed, and only mature MII oocytes were injected.

Oocyte maturity was evaluated approximately 2 hours after the retrieval, just prior to sperm injection, using a Leica DMIRB inverted microscope (Wetzlar, Germany) at

Fertilization was assessed between 16 to 18 hours post-insemination/injection by examining the presence of two pronuclei and the extrusion of the second polar body (PB) into the perivitelline space (PVS). The fertilization rate was calculated as the ratio of oocytes displaying two pronuclei (2PN) to the total number of oocytes inseminated or injected.

Cleavage-stage embryos were scored according to the Puissant criteria, which consider the number and size of blastomeres and the percentage of anucleate fragments [18]. The cleavage rate (day 3 embryo formation rate) was defined as the ratio of the total number of day 3 embryos by the total number of fertilized oocytes.

On day 3, an embryo was classified as high-quality if it exhibited eight uniformly-sized blastomeres, no multi-nucleation, and less than 10% fragmentation.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24 software (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA). The normality of the data was evaluated using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Non-parametric variables were analyzed using the Mann-Whitney U test to compare the IVF following short IVM and ICSI groups. For comparisons of qualitative variables, the Chi-square test was applied.

Data are presented as mean

In this study, 71 patients were excluded due to having fewer than six COCs. Of these patients, 31 (28.18%) belonged to the stage I–II endometriosis group, while 40 patients (42.1%) were from the stage III–IV endometriosis group. Consequently, a significant difference in the dropout rate was observed between the groups, with the stage III–IV group exhibiting a notably higher dropout rate (p = 0.037).

Demographic data and clinical characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 1. The mean age of patients in the stage I–II endometriosis group was 33

| Parameters | Groups | ||

| Stage III–IV | Stage I–II | p-value | |

| Endometriosis (N = 55) | Endometriosis (N = 79) | ||

| Age (years) (Mean | 34 | 33 | 0.250# |

| BMI (kg/m2) (Mean | 22.8 | 22.6 | 0.210# |

| Infertility duration (Mean | 6 | 5 | 0.320# |

| AMH (Mean | 2.92 | 3.54 | 0.003# |

| LH (mIU/mL) (Mean | 3.9 | 3.3 | 0.130# |

| Serum E2 level on the day of hCG (pg/mL) | 1432.89 | 1855.7 | 0.026# |

| Antral follicle count | 8.8 | 9.9 | 0.029#* |

| Number of retrieved oocyte (Mean | 7.51 | 9.7 | 0.032#* |

| Maturity rate a (%) | 56 | 72 | |

| Fertilization rate b (%) | 59 | 72 | |

| Complete fertilization failure c (%) | 2.72 | 0.94 | 0.013‡* |

| Embryo formation rate d (%) | 88 | 89 | 0.462‡ |

| Day 3 top quality rate e (%) | 69 | 72 | 0.810‡ |

BMI, body mass index; LH, luteinizing hormone; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; AMH, anti-mullerian hormone; E2, Estradiol; N, Number.

a The ratio of metaphase II (MII) oocytes to the total number of obtained oocytes.

b The ratio of fertilized oocytes to the total number of inseminated or injected oocytes.

c The percentage of patients whose oocytes all failed to exhibit two pronuclei (PN).

d The ratio of day 3 embryos to the total number of fertilized oocytes.

e The ratio of high-quality embryos to the total number of embryos.

# Mann-Whitney U test.

‡ Chi-square test.

*p

Table 2 presents the fertilization and embryo formation outcomes of oocytes inseminated via conventional IVF following short IVM or ICSI in the stage I–II endometriosis group. No significant differences were observed between the ICSI and IVF subgroups in terms of the mean number of fertilized oocytes, embryos, day 3 top-quality embryos, and rates of fertilization, and embryo formation.

| Parameters | Stage I–II ICSI (N = 79) | Stage I–II IVF (N = 79) | p-value |

| Number of inseminated oocyte (Mean | 4.53 | 3.67 | 0.001#* |

| Number of fertilized oocyte (Mean | 2.62 | 2.59 | 0.911# |

| Number of embryo (Mean | 2.18 | 2.09 | 0.659# |

| Number of day 3 high-quality embryo (Mean | 1.73 | 1.66 | 0.679# |

| Fertilization rate (%) | 73% | 70% | 0.543‡ |

| Embryo formation rate (%) | 90% | 86% | 0.444‡ |

| Day 3 top-quality embryo rate (%) | 71% | 67% | 0.570‡ |

IVM, in vitro maturation; IVF, in vitro fertilization; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

# Mann-Whitney U test.

‡ Chi-square test.

*p

Table 3 shows the fertilization and embryo formation outcomes of oocytes inseminated by conventional IVF following short IVM or ICSI in the stage III–IV endometriosis group. No significant differences were observed between the ICSI and IVF subgroups in terms of the mean number of fertilized oocytes, embryos, day 3 top-quality embryos, as well as the rates of fertilization, and embryo formation…

| Parameters | Stage III–IV ICSI (N = 55) | Stage III–IV IVF (N = 55) | p-value |

| Number of inseminated oocyte (Mean | 4.31 | 2.71 | |

| Number of fertilized oocyte (Mean | 1.51 | 1.47 | 0.883# |

| Number of embryo (Mean | 1.20 | 1.20 | 0.901# |

| Number of day 3 high-quality embryo (Mean | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.858# |

| Fertilization rate (%) | 63% | 55% | 0.230‡ |

| Embryo formation rate (%) | 88% | 90% | 0.842‡ |

| Day 3 top-quality embryo rate (%) | 71% | 72% | 0.934‡ |

IVM, in vitro maturation; IVF, in vitro fertilization; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection.

# Mann-Whitney U test.

‡ Chi-square test.

*p

In the current study, we examined patients with different stages of endometriosis and partners with normozoospermic semen, in whom sibling oocytes were randomly inseminated either by conventional IVF following short IVM or ICSI. The findings revealed the following key observations: (i) the dropout rate and complete fertilization failure were notably higher in the stage III–IV endometriosis group compared to the stage I–II endometriosis group; (ii) within the stage I–II endometriosis group, basal serum AMH levels, the mean number of retrieved oocytes, as well as the rates of maturity and fertilization were significantly higher than in the stage III–IV endometriosis group; (iii) despite the insemination method, there were no significant differences in fertilization rates, embryo formation, or the proportion of day 3 top-quality embryos within each endometriosis group.

Studies have indicated that the severity of endometriosis, categorized into stages I to IV, may influence the quality of follicles/oocytes, embryo development, and their viability [2, 19]. In cases of minimal to mild (stage I–II) endometriosis, evidence suggests that oocyte and embryo quality may be relatively preserved, with fewer impairments in fertilization and embryo development. However, in more advanced stages (stage III–IV) of endometriosis, there appears to be an increased risk of reduced ovarian reserve and oocyte numbers, a higher likelihood of cycle cancellations, and compromised oocyte and embryo quality [2, 20]. This may be attributed to increased pelvic inflammation, higher oxidative stress, disruptions in steroid synthesis, and altered ovarian function [21, 22]. These factors collectively affect the follicular environment, leading to an increased risk of meiotic abnormalities, chromosomal instability, and alterations in oocyte morphology [23]. Consequently, these changes compromise oocyte quality, which, in turn, can impair embryo development.

Consistent with some previous observations, our findings also showed that as endometriosis progresses, there is a decrease in the number of retrieved oocytes, mature oocytes, and fertilization rates, along with an increase in complete fertilization failure. However, we did not find a significant difference in the rates of embryo formation and top-quality embryos. Dong et al. [24] revealed that, despite a significantly lower number of retrieved oocytes, there were no statistically significant differences between the stage III–IV endometriosis group and the stage I–II group regarding fertilization rate and the rate of high-quality embryos on day 3. A recent systematic review and meta-analysis of 22 studies assessing the influence of endometriosis on embryo quality also found that in women with stage III–IV endometriosis, there were no statistically significant differences in high-quality embryo rates, cleavage rates, or embryo formation rates when compared to those without endometriosis [25]. Women who undergo surgery for moderate to severe endometriosis have been reported to have a comparable number of cleavage embryos and good-quality embryos when compared to women without endometriosis [26]. Conversely, Pellicer and colleagues [12] discovered that women with stage III–IV endometriosis exhibited reduced embryo quality and a higher incidence of arrested embryos. Nevertheless, our findings on embryo quality should be interpreted with caution, as there are currently no universally accepted criteria or terminology for embryo morphological assessment worldwide. Moreover, the morphological grading of embryos is highly subjective, which limits its predictive certainty [27].

Notably, as the development of the human embryo is directly influenced by both the nuclear and cytoplasmic maturation of the oocyte, and considering that endometriosis can impair the quality of the surrounding follicular fluid and, subsequently, the oocytes maturation environment, we implemented a brief IVM period after oocyte retrieval and before commencing IVF to enhance oocyte maturation. Interestingly, we observed similar fertilization rates, embryo formation, and production of high-quality day 3 embryos when comparing sibling oocytes subjected to ICSI or IVF following the short IVM period, in both stage I–II and stage III–IV groups. In contrast, a previous study by Komsky-Elbaz et al. [1] found a significantly higher fertilization rate of oocytes inseminated by ICSI, yielding a significantly higher mean number of day 2 embryos, as well as a higher mean number of embryos suitable for cryopreservation, compared to conventional IVF in patients with severe endometriosis and normozoospermic semen. For most IVF programs, higher rates of fertilization and embryo formation are expected following ICSI compared to conventional IVF. However, due to the lack of detailed information regarding culture conditions in the previous study, this discrepancy in our findings may be cautiously attributed to the short IVM period employed in our approach.

The present study has several limitations that should be noted. Firstly, we did not assess the rate of blastocyst formation, which serves as a critical indicator of embryo developmental competence. Additionally, our study did not consider implantation rates, clinical pregnancy rates, or live birth rates as primary outcome measures due to the inclusion of patients undergoing a frozen embryo transfer strategy. A strength of the present study was the use of the sibling oocyte model to evaluate the most effective ART approach in endometriosis, as interpatient variability is a significant confounding factor.

Our findings suggest that conventional IVF following a short IVM period produces comparable outcomes to ICSI in patients with varying stages of endometriosis. This indicates that IVF with a brief IVM period can serve as an equally effective, yet less invasive, alternative to ICSI for treating endometriosis-associated infertility.

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to privacy reason but are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

MM, HGT, EN, and MarzD designed the research study. MarzD and MaryD performed the research. SGS did the data collection. MarzD and ES analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee, Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran (Approval ID: IR.MUI.MED.REC.1402.313) and confidentiality of the data was ensured. This study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants included in the study.

The authors wish to acknowledge the staff at Shahid Beheshti Hospital and Zeinabieh IVF center and the participants for their assistance in this study. Moreover, we would like to thank Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, Isfahan, Iran, for financial support.

This work was supported by Isfahan University of Medical Sciences (Grant number: 3402437).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGpt-3.5 in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.