1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Pamukkale University, 20070 Denizli, Turkey

2 Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism, Department of Internal Medicine, Faculty of Medicine, Pamukkale University, 20070 Denizli, Turkey

3 Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Medicine, Pamukkale University, 20070 Denizli, Turkey

Abstract

This study aimed to investigate serum levels of calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) and explore potential associations between serum CGRP, adiponectin, and ghrelin concentrations in patients with preeclampsia.

This study evaluated 43 normotensive healthy pregnant women and 36 pregnant women diagnosed with preeclampsia. Serum concentrations of CGRP, adiponectin, and ghrelin were measured in both groups during the third trimester of pregnancy.

Serum concentrations of CGRP were significantly elevated in the preeclampsia group compared to the control group. Conversely, the preeclampsia group exhibited significantly decreased serum levels of adiponectin and ghrelin relative to the controls. No significant correlation was observed between serum CGRP levels and adiponectin or ghrelin levels in either the preeclampsia or control groups.

Our study demonstrates a considerable increase in serum CGRP concentrations in patients with preeclampsia compared to the control group. These outcomes strongly indicate that CGRP may play a pivotal role in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia.

Keywords

- preeclampsia

- calcitonin gene-related peptide

- ghrelin

- adiponectin

Preeclampsia is a serious pregnancy disorder that typically occurs after the 20th week of gestation, characterized by new-onset hypertension accompanied by proteinuria or by significant end-organ dysfunction in the absence of proteinuria [1]. The global prevalence of preeclampsia varies between 2% and 8% of all pregnancies [2]. This variation is largely attributed to differences in population characteristics such as the ratio of nulliparous pregnant women in the population and the average age of pregnant women. Preeclampsia is a leading cause of perinatal and maternal morbidity or mortality worldwide. Women diagnosed with the preeclampsia face increased risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, stroke, and reduced life expectancy. Similarly, newborns from preeclamptic women are at elevated risk of perinatal death, preterm birth, neurodevelopmental disability, and metabolic and cardiovascular disease later in life [3, 4, 5]. It is estimated that over 300 million women and children with a history of preeclampsia exposure are at high risk for chronic health conditions worldwide [6]. Despite its multiple comorbidities, the underlying cause of preeclampsia in some pregnant women remains unclear. A better understanding of its pathophysiology and improved early diagnosis methods are crucial to reduce associated health complications.

Preeclampsia is clinically classified according to the gestational age at presentation. The International Society for the Study of Hypertension in Pregnancy (ISSHP) classifies preeclampsia as preterm (delivery

A typical pregnancy is categorized by a range of metabolic and endocrine variations, including decreased vascular resistance that begins immediately after conception to support fetal growth. Disruption of this adaptive mechanism during pregnancy can lead to significant complications. Although the underlying mechanisms of preeclampsia are not fully understood, endothelial dysfunction is strongly associated with its pathogenesis [12, 13].

Calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) is a neuropeptide composed of 37 amino acids [14]. Its most well-documented effect is its strong potent vasodilatory activity, a or the ability to widen blood vessels [15]. CGRP is primarily found in both the central and peripheral nervous systems, but it is also present in non-neuronal tissues such as the cardiovascular, endocrine, and gastrointestinal systems [16, 17]. Despite several previous research, the precise metabolic role of CGRP remains unclear. However, the in vitro study has shown that this peptide plays an important role in mediating vasodilation, especially during pregnancy [18]. Systemic infusion of CGRP has been shown to decrease blood pressure in a dose-dependent manner in spontaneously hypertensive rats, as well as in normotensive humans and animals [19, 20]. During pregnancy, serum CGRP concentrations significantly increase in women, followed by a decrease in the postpartum period [21]. This observation indicates a potential role for elevated CGRP levels in promoting vascular endothelial adaptation and blood pressure regulation during pregnancy.

Adiponectin is a polypeptide hormone produced by adipose tissue that regulates lipid metabolism, glucose metabolism, angiogenesis, and inflammatory processes [22]. Adiponectin is associated with insulin resistance, obesity, and hypertension [23, 24]. During a healthy pregnancy, serum adiponectin concentrations gradually decline, particularly in the third trimester, in response to physiological changes [25]. Previous studies have shown that adiponectin interacts with several risk factors of preeclampsia such as insulin resistance, abnormal vascular reactivity, and inflammatory disorders. This evidence suggests that adiponectin may play a role in preeclampsia [26, 27, 28]. However, the findings regarding adiponectin levels in preeclampsia remain inconsistent across the literature.

Ghrelin, a peptide hormone consisting of 28 amino acids, is primarily synthesized by the stomach, with smaller amounts produced in pancreatic cells, the hypothalamus, kidneys, heart, adrenal glands, and placenta [29, 30, 31]. The study has highlighted its significant role in cardiovascular and sympathetic regulation [32]. Intravenous administration of ghrelin has been shown to reduce blood pressure in a dose-dependent manner in both healthy individuals and animal models [32, 33, 34]. Additionally, ghrelin may contribute to blood pressure regulation in both animals and humans. Previous studies have investigated its potential role in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia [35, 36]. However, its role in the physiological processes of pregnant women with preeclampsia remains unclear, as studies examining ghrelin levels in this condition have yielded contradictory results.

Based on the aforementioned discussions, the role of CGRP in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia remains controversial. The primary objective of this study was to evaluate CGRP levels in pregnant women diagnosed with preeclampsia. Furthermore, the study aimed to examine potential associations between serum levels of CGRP, adiponectin, and ghrelin, as well as the influence of these molecules in pathogenesis of preeclampsia.

This investigation was designed as a single-center, multidisciplinary, cross-sectional study. It was conducted between February 2019 and September 2020 at the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Pamukkale University Hospital, a tertiary care center in Denizli, Turkey. The study was approved by the Non-Interventional Ethics Committee of Pamukkale University and conducted in accordance with the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (Ethics Committee Approval No: 60116787-020/13223, Date: 20/02/2019). All pregnant women were informed about the study, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

A total of 79 pregnant women with singleton pregnancies between 30–32 weeks of gestation, along with their healthy newborns, were included in the study. Gestational age for each pregnant woman was calculated based on the first day of their last menstrual period and confirmed through previous medical records and routine ultrasound examinations. Height and weight measurements were obtained from all participating pregnant women. Maternal body mass index (BMI) was calculated using the standard formula: weight (kg)/height2 (m2). These calculations were performed at the time of blood sample collection. Pregestational weight and BMI were also determined. Patient records provided additional medical information, including maternal age, parity, gravida, number of abortion, as well as reproductive and medical history. Neonatal data collected at delivery included gestational age and birth weight.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommended new criteria in 2020 for the diagnosis of preeclampsia [1]. In this study, new diagnostic criteria recommended by ACOG were used for the identification of preeclampsia. Preeclampsia was diagnosed based on the new onset of hypertension (systolic blood pressure

Venous blood samples (10 mL each) were collected from pregnant women immediately after preeclampsia was diagnosed at 30–32 weeks of gestation. In addition, at 30–32 weeks of gestation, venous blood samples (10 mL) were obtained from normotensive healthy pregnant women in our clinic for the control group. Blood samples were collected in the gynecology and obstetrics clinic and immediately transported in a plasma transport cooler box to the biochemistry laboratory on the upper floor. There, the serum samples were separated by centrifugation in plain gel tubes for approximately 40 minutes at 4 °C using a refrigerated centrifuge. The obtained serum samples were stored at –80 °C until further analysis. Before analysis, the frozen sera were thawed at room temperature, and 100 µL of each sample was used for the analysis.

Human CGRP serum levels were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Catalog Number: CSB-E08210h, Cusabio, Wuhan, Hubei, China). Similarly, human adiponectin levels were assessed using sandwich-ELISA kits (Catalog Number: CSB-E07270h, Cusabio), and human ghrelin levels were quantified with ELISA kits (Catalog Number: CSB-E13398h, Cusabio). Serum levels were measured with ELISA kits according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Optical densities (ODs) were recorded at 450 nm to quantify the serum levels of CGRP, adiponectin, and ghrelin in pg/mL.

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS for Windows, version 23.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Both parametric (Student’s t-test) and non-parametric (Mann-Whitney U test) methods were used for the analyses. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate the relationships between variables. Additionally, multiple logistic regression was employed to validate the data. Adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis was utilized to determine the optimum CGRP cut-off value. Results were presented as mean

36 pregnant women with preeclampsia and 43 normotensive healthy pregnant women without complications, as well as their neonates, were evaluated in this study. The comparative demographic and clinical characteristics of these are shown in Table 1. The mean age of pregnant women with preeclampsia was 29.55

| Variables | Preeclampsia Group (n = 36) | Control Group (n = 43) | p-value |

| Age (years) | 29.55 | 30.11 | 0.536 |

| Gravida | 2 (1–5) | 2 (1–6) | 0.107 |

| Parity | 0 (0–4) | 1 (0–5) | 0.054 |

| Number of Miscarriages | 0 (0–2) | 0 (0–2) | 0.436 |

| Gestational age at birth (weeks) | 33.36 | 38.46 | 0.000* |

| BMI at delivery (kg/m2) | 34.86 | 29.78 | 0.000* |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI (kg/m2) | 30.32 | 25.37 | 0.000* |

| Weight gain during pregnancy (kg) | 11.86 | 11.44 | 0.746 |

| Neonates birth weight (g) | 2467.77 | 3264.18 | 0.000* |

The data are presented as mean

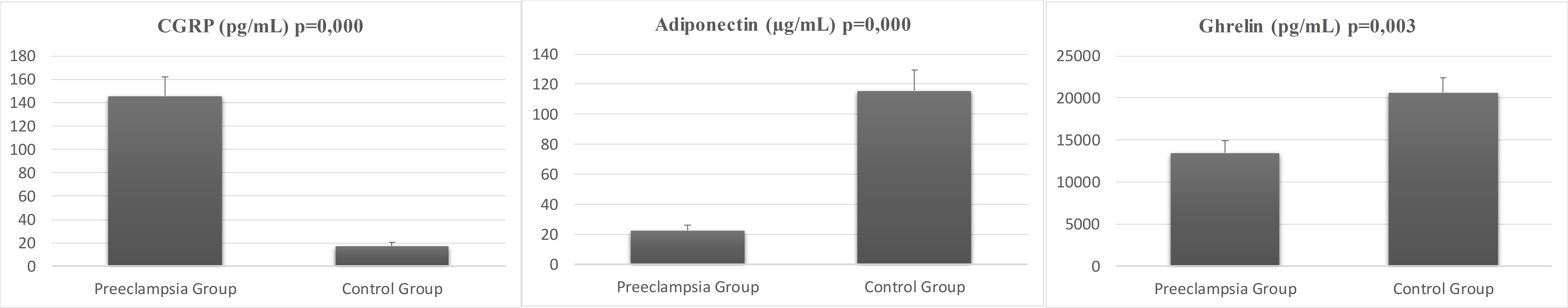

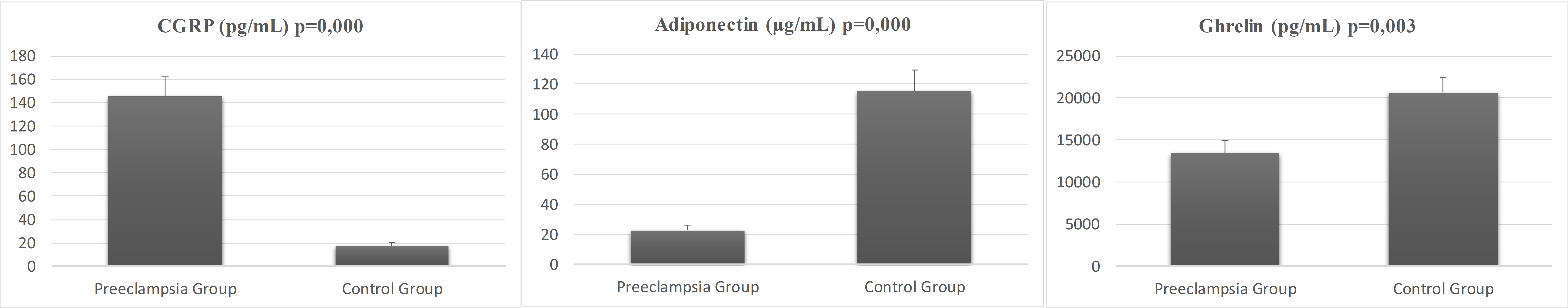

Fig. 1 illustrates the comparative serum concentrations of CGRP, adiponectin, and ghrelin in pregnant women with preeclampsia versus the control group. The average CGRP level in pregnant women with preeclampsia was 145.53

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Serum concentrations of CGRP, adiponectin, and ghrelin for preeclampsia and control groups. CGRP, calcitonin gene-related peptide.

Table 2 shows the correlation coefficients between serum CGRP concentrations and various evaluated parameters in both the preeclampsia and control groups, as well as in the overall research cohort. In the preeclampsia group, a statistically significant, positive, weak positive correlation was observed between parity and adiponectin levels (r = 0.327). This correlation was statistically insignificant in the control group. Also, the preeclampsia group demonstrated a statistically significant, negative, and weak correlation between weight gain during pregnancy and CGRP (r = –0.292), whereas no significant correlation was observed in the control group.

| Control Group (n = 43) | Preeclampsia Group (n = 36) | ||||||

| CGRP | Adiponectin | Ghrelin | CGRP | Adiponectin | Ghrelin | ||

| Age | r | –0.074 | 0.080 | –0.137 | –0.038 | –0.022 | –0.011 |

| p | 0.319 | 0.306 | 0.190 | 0.413 | 0.450 | 0.476 | |

| Parity | r | 0.215 | 0.047 | –0.147 | 0.119 | 0.327* | –0.204 |

| p | 0.083 | 0.383 | 0.173 | 0.248 | 0.026 | 0.117 | |

| Maternal weight at birth | r | 0.310* | –0.163 | –0.295* | –0.015 | 0.198 | –0.076 |

| p | 0.021 | 0.148 | 0.027 | 0.466 | 0.124 | 0.331 | |

| BMI at birth | r | 0.343* | –0.273* | –0.379* | –0.099 | 0.154 | –0.112 |

| p | 0.012 | 0.038 | 0.006 | 0.285 | 0.185 | 0.258 | |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | r | 0.280* | –0.171 | –0.308* | 0.017 | 0.175 | –0.103 |

| p | 0.035 | 0.136 | 0.022 | 0.462 | 0.154 | 0.276 | |

| Weight gain during pregnancy | r | 0.062 | –0.136 | –0.044 | –0.292* | –0.031 | –0.020 |

| p | 0.346 | 0.193 | 0.390 | 0.044 | 0.428 | 0.454 | |

| Neonates birth weight | r | –0.039 | –0.106 | 0.141 | –0.233 | –0.009 | 0.084 |

| p | 0.402 | 0.250 | 0.184 | 0.089 | 0.479 | 0.314 | |

| CGRP | r | 1 | –0.127 | –0.227 | 1 | –0.024 | –0.167 |

| p | 0.208 | 0.072 | 0.446 | 0.169 | |||

| Adiponectin | r | 1 | 0.690* | 1 | 0.118 | ||

| p | 0.000 | 0.247 | |||||

| Ghrelin | r | 1 | 1 | ||||

| p | |||||||

* p

No significant correlation was observed between maternal weight any of the serum biomarkers in the preeclampsia group. The control group exhibited a statistically significant, positive, and weak correlation between weight and CGRP (r = 0.310), as well as a statistically significant, negative, and weak correlation with ghrelin (r = –0.295). Similarly, no significant correlation was found with BMI in the preeclampsia group. In the control group, there was a statistically significant, positive, and weak correlation between BMI and CGRP levels (r = 0.343), a statistically significant, negative, and weak correlation with adiponectin (r = –0.273), and ghrelin (r = –0.379). No significant correlation was found with pre-pregnancy BMI in the preeclampsia group. The control group had a statistically significant positive and weak correlation between pre-pregnancy BMI and CGRP (r = 0.28), as well as a statistically significant negative and weak correlation with ghrelin (r = –0.308). The control group demonstrated a statistically significant, positive, and moderate correlation between adiponectin and ghrelin levels (r = 0.69). This correlation was not statistically significant in the preeclampsia group.

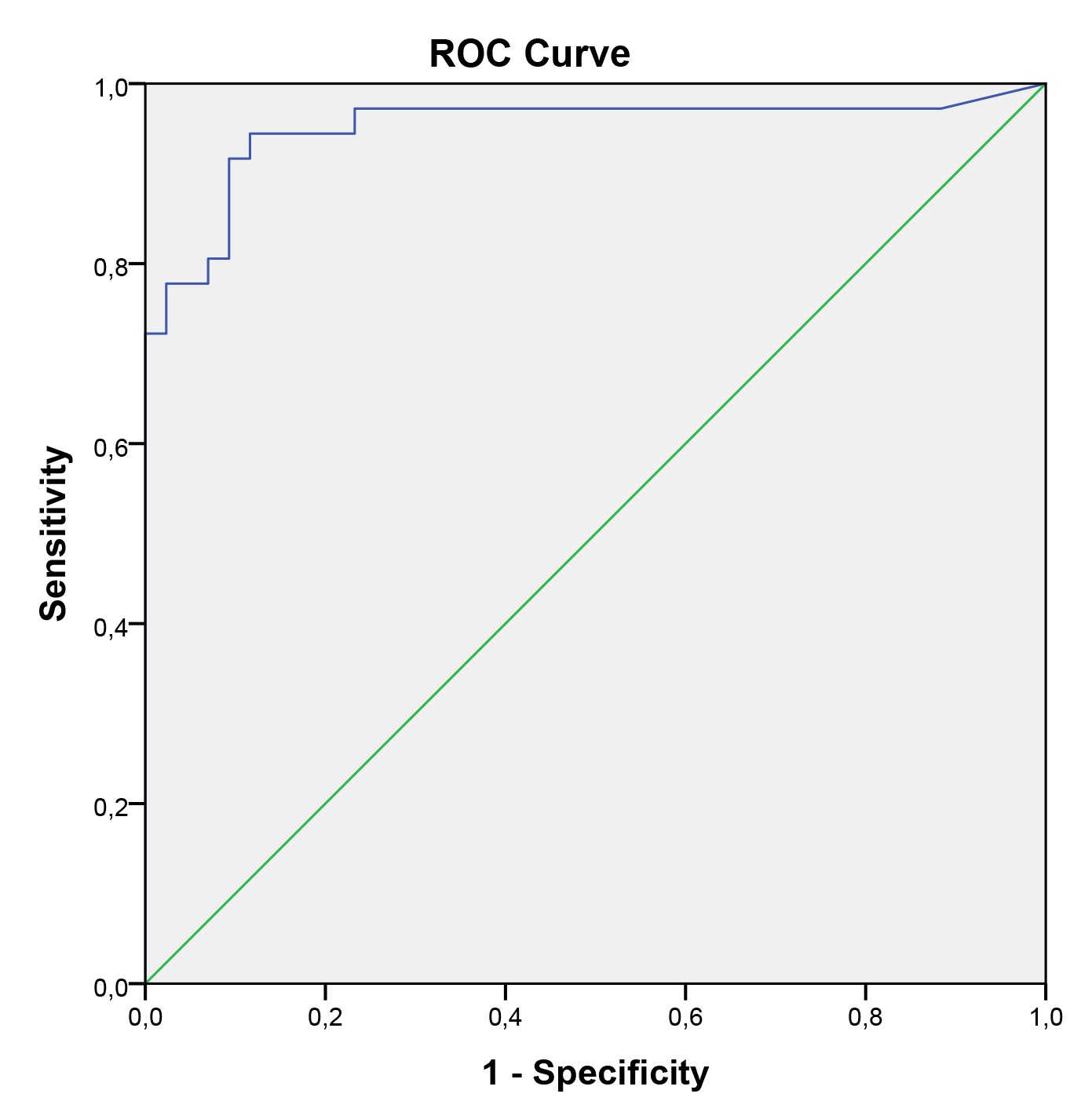

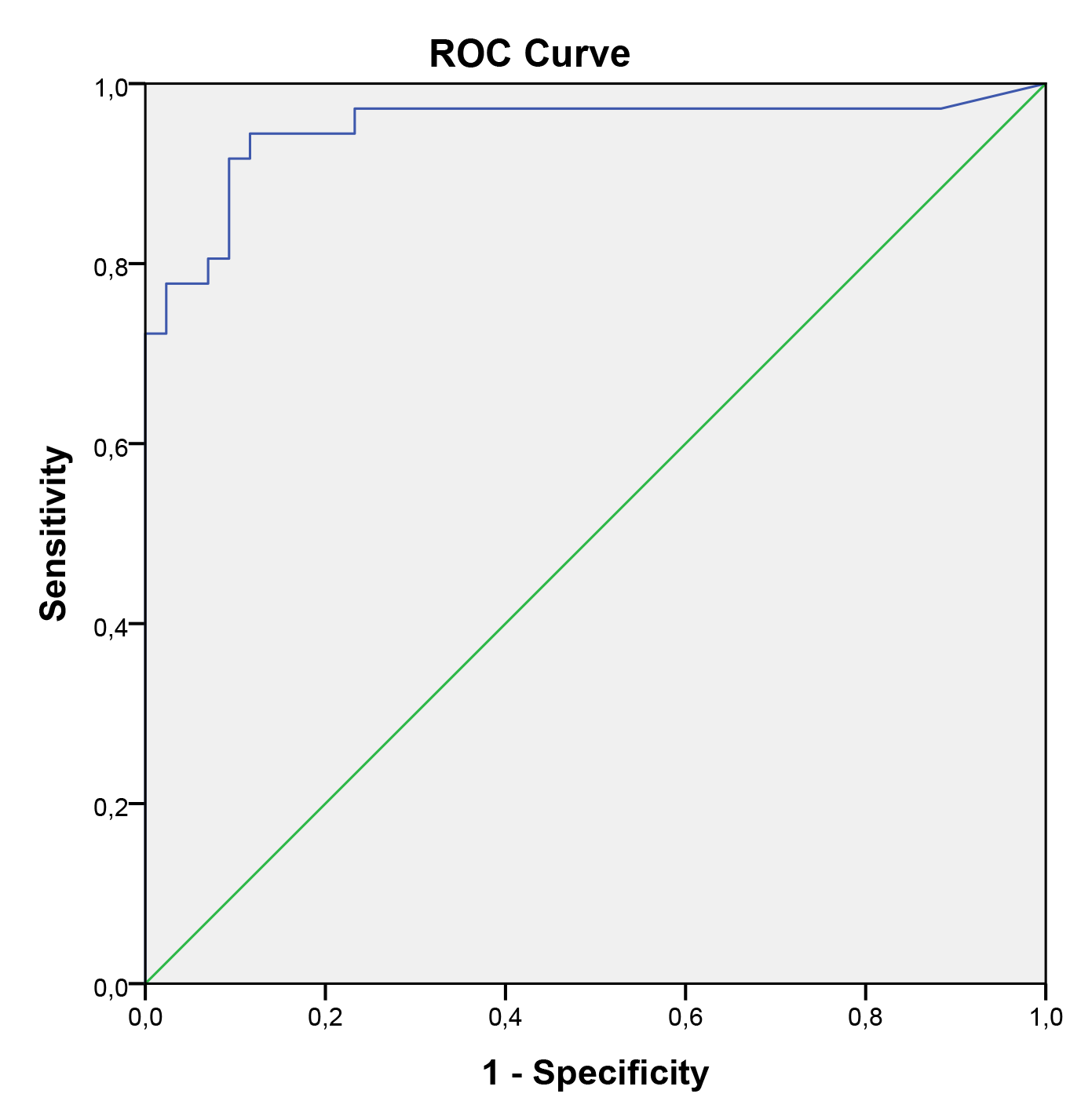

In the univariate logistic regression model, pre-pregnancy BMI, neonatal birth weight, and serum CGRP levels were identified as significant predictors for preeclampsia. However, in the multivariate logistic regression model, serum CGRP levels were the only significant predictor of preeclampsia. Regardless of pre-pregnancy BMI and neonatal birth weight, serum CGRP levels were higher in pregnant women with preeclampsia compared to those without preeclampsia. Serum CGRP level was identified as an independent predictor of preeclampsia in pregnant women. Table 3 shows the results of multiple logistic regression analyses for preeclampsia in pregnant women. These analyses indicated that serum CGRP levels are a significant indicator of preeclampsia during the third trimester of pregnancy. The ROC curve analysis yielded an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.951 (95% CI: 0.895–1.000). To predict preeclampsia, a serum CGRP value of 40.5 was identified as the optimal cutoff, with a sensitivity of 91.7% and specificity of 90.7% (Fig. 2).

| Variables | Wald | p | OR (95% CI) | |

| CGRP | 0.059 | 11.474 | 0.001* | 1.060 (1.025–1.097) |

| Neonates birth weight | –0.002 | 3.728 | 0.054 | 0.998 (0.867–1.253) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI | 0.042 | 0.197 | 0.657 | 1.043 (0.998–1.277) |

* p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. ROC for CGRP in predicting preeclampsia (AUC for ROC, 0.951; 95% CI, 0.895–1.000). ROC, receiver operator curve; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval.

The extensive neural networks of motor and sensory nerves are responsible for synthesizing and releasing CGRP, highlighting its diverse metabolic functions across various biological processes. For instance, CGRP acts as a potent vasodilatory agent, influencing vascular tone [18], and has been shown to decrease blood pressure in both in vivo and in vitro models [19, 20]. Additionally, it seems that CGRP is linked to the physiological adaptations that occur during pregnancy [21]. These data suggest that CGRP may play a major role in regulating peripheral vascular resistance both under the normal physiological conditions during pregnancy and in the pathophysiology of preeclampsia [18, 37, 38]. These results are consistent with the findings of our study. This investigation identified a significant increase in serum CGRP levels in preeclampsia. Furthermore, regression analysis indicated that only serum CGRP levels were independently associated with preeclampsia.

Increasing serum CGRP levels in preeclampsia may contribute to maternal adaptation of vascular endothelial cell function and blood pressure regulation during pregnancy. Masuda et al. [39] conducted a study in hypertensive patients and suggested that increased serum CGRP levels may be a compensatory response to high blood pressure. Supowit et al. [40] performed a study using a rat model and reported that increased CGRP synthesis and release in hypertension serve as a compensatory depressor response associated with the reduction of elevated blood pressure. Furthermore, Yallampalli and Wimalawansa [41] conducted a study using a rat model and suggested that hypertension during pregnancy may result from the failure of compensatory vasodilatory functions mediated by CGRP. The results of the present investigation provide further support for this hypothesis. Our outcomes suggest that maternal circulating CGRP may play a key role in the compensatory vasodilation responsible for mitigating hypertensive disorders during pregnancy. Failure of CGRP-mediated compensatory vasodilation may result in preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction [41]. Preeclampsia is often related to fetal growth restriction [42]. The results show that the mean birth weight of neonates was significantly lower in the preeclampsia group; however, no significant correlation was found with CGRP. In normal pregnancy, serum CGRP concentrations are elevated in both maternal and fetal circulation [21]. Fetal serum CGRP concentration is associated with fetal weight [43]. Dong et al. [44] conducted a study involving 6 subjects with preeclampsia and 6 subjects in the control group, and they observed that decreased CGRP levels in both maternal and fetal circulation may be associated with the pathogenesis of preeclampsia and fetal growth restriction. Furthermore, Dong et al. [45] conducted a study involving 8 groups with preeclampsia and 8 control groups, and they reported decreased CGRP levels in both pregnant women and fetal circulation in preeclampsia. These results are in disagreement with those of our study. However, this study was conducted with very small sample size. CGRP has been implicated in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Some studies reported higher CGRP levels in preeclamptic patients compared to controls, which may be due to the small sample sizes. On the other hand, Yadav et al. [46] reported that CGRP levels were decreased in pregnant women with preeclampsia and were positively correlated with neonatal birth weight. Halhali et al. [47] conducted a study involving 25 women with preeclampsia and 25 controls, and found decreased CGRP levels in pregnant women with preeclampsia. Furthermore, magnesium sulfate therapy increased CGRP levels in the preeclampsia group [47]. Similarly, Fondjo et al. [48] conducted a study in 2023 on 50 women with severe preeclampsia, 50 women with mild preeclampsia, 50 normotensive subjects. Their findings also reported an increase in CGRP levels following MgSO4 treatment in the preeclampsia group [48]. However, in both studies, serum CGRP levels were higher in the control group compared to the preeclampsia group [47, 48]. In this present study, we measured serum CGRP levels only prior to MgSO4 treatment. Many studies cite the short half-life of CGRP as a primary limitation of their research [49, 50]. However, a recent review and comprehensive experimental analysis concluded that, in addition to buffering with a peptidase inhibitor, the most effective method for preserving CGRP content is the immediate freezing of samples [49, 50]. The observed increase in CGRP levels following magnesium sulfate treatment in preeclampsia patients supports both the vasodilatory role of CGRP and its association with the pathophysiology of preeclampsia. The results of the presented study suggest that increased serum CGRP levels may represent a compensatory response to hypertension. Although this variability may be attributed to differences in sample collection methods, biochemical analyses, sample size, patient ethnicity, population heterogeneity, and study design, these studies consistently highlight an association between CGRP and preeclampsia.

Considering these findings, the weight gain observed in preeclampsia is believed to result from edema rather than increased adipose tissue. Additionally, CGRP appears to contribute to endothelial dysfunction, which is strongly associated with the pathogenesis of preeclampsia.

Adiponectin is a polypeptide hormone primarily released by adipose tissues and is believed to be involved in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia. Adiponectin regulates key processes such as hypertension, systemic inflammation, placentation, endothelial dysfunction, and proteinuria, all of which are implicated in the development of preeclampsia [51]. Previous studies have reported both decreased [52, 53, 54, 55] and increased [56, 57, 58, 59] serum adiponectin levels in preeclampsia. Also, a recent review has reported increased serum adiponectin levels in preeclamptic women of normal weight, and decreased serum levels in those who were overweight or obese [53]. The results of this study validate the existing evidence, showing that maternal adiponectin levels are decrease in preeclamptic women who are overweight or obese. The correlation analysis conducted in this study showed a relationship between adiponectin levels and BMI in the control group. A weak negative correlation between BMI and adiponectin levels was observed. Although this difference may be attributed to variations in pregnancy stages, tissue types, population heterogeneity, these studies underscore the relation between adiponectin and preeclampsia.

Ghrelin is a peptide hormone synthesized in various tissues, particularly the stomach and is believed to have an important role in the regulation of the cardiovascular and sympathetic systems [32]. Recently studies have shown that ghrelin exerts beneficial effects on blood pressure regulation. Li et al. [60] performed a study on 14 participants in the hypertension group and 14 in the control group. The study reported that ghrelin levels and the ghrelin-to-obestatin ratio were lower in the hypertension group. Ghrelin can directly vasodilate blood vessels, promote diuresis, and regulate the sympathetic nervous system to lower peripheral vascular resistance [61]. Furthermore, ghrelin is believed to play an important role in improving endothelial function [62]. Wu et al. [36] performed a study on 31 preeclampsia patients and 31 control subjects. It was reported that maternal ghrelin levels and the ghrelin-to-obestatin ratio were lower in preeclampsia. Our results validate existing evidence, demonstrating a reduction in maternal ghrelin levels in preeclampsia. Erol et al. [35] conducted a study on late-onset preeclampsia and reported that ghrelin levels were higher in preeclampsia and correlated with disease severity. The variations in these findings may be attributed to differences in study designs.

This single-center study has several limitations. It was performed with a limited number of pregnant participants, and blood samples were collected only once at 30–32 weeks of gestation. Moreover, no information was available regarding first- and second-trimester CGRP levels and their association with the development of preeclampsia. Additionally, pregnant women were not classified according to the severity of preeclampsia (mild or severe). Lastly, the inability to determine placental CGRP expression and its influence on serum levels during pregnancy represents another major limitation of the study.

The findings of this study indicate elevated serum CGRP levels in cases of preeclampsia. These results suggest that increased CGRP levels may play a crucial role in the pathogenesis of preeclampsia during pregnancy. The elevation of serum CGRP levels might represent a compensatory response to preeclampsia. However, extensive and prospective research is needed to determine whether increased CGRP levels could serve as a predictive marker for the screening and development of preeclampsia.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

OKC: Conceptualization (equal); data curation (lead); formal analysis (lead); investigation (lead); project administration (equal); writing — original draft (lead); writing — review and editing (lead). UC: Data curation (equal). CK: Data curation (equal). SF: Conceptualization (lead); data curation (equal); supervision (lead); writing — review and editing (equal). VF: Conceptualization (equal); formal analysis (equal); project administration (equal); supervision (equal); writing — review and editing (supporting). YE: Data curation (lead). All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study received approval from the non-interventional ethics committee of Pamukkale University and adhered to the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration (Ethics Committee Approval No: 60116787-020/13223, Date: 20/02/2019). All pregnant women were informed about the study, and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Authors present thanks to Pamukkale University. Authors are also grateful to the Prof. Dr. Ömer Tolga Güler for supports in data collection. Authors are also grateful to the Asst. Prof. Dr. Hande Şenol for supports in statistical analysis.

This research project was supported by the Pamukkale University Scientific Research Council (Grand No: 2019HZDP014).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.