1 Biotechnology Research Center, Tabriz University of Medical Sciences, 5165665813 Tabriz, Iran

Abstract

The reproductive health and quality of life of women are profoundly affected by uterine fibroids, which are benign tumors of the myometrium. By reviewing the existing literature, speculating on possible causes, and drawing attention to gaps in our understanding, this review seeks to delve into the complex system of links between uterine fibroids and cancer susceptibility. Future research on women’s health could benefit from considering the findings of this review, alongside emerging evidence, to inform clinical decision-making.

This review examines the epidemiology and clinical relevance of uterine fibroids, which are widespread and significantly affect women’s health. This review explores the molecular causes and pathophysiology of uterine fibroids with a focus on genetic, epigenetic, and hormonal factors. It also evaluates the correlation between fibroids and various cancers, such as endometrial cancer and leiomyosarcoma, while addressing the challenges of distinguishing benign from malignant tumors and the potential causes of malignant transformation.

Uterine fibroids are typically benign, but they have the potential to become malignant in certain cases. Therefore, early diagnosis and effective treatment methods, including histopathology, cancer biomarkers, and advanced imaging techniques, are crucial for identifying and managing malignant transformation. Patient education is vital for empowering individuals to recognize the early signs and symptoms of uterine fibroids, leading to timely medical consultation and better management outcomes.

This review emphasizes the need for continued research to refine our understanding of the relationship between uterine fibroids and cancer risk with the aim of enhancing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies to improve patient outcomes.

Keywords

- uterine fibroids

- gynecological cancer risk

- leiomyosarcoma

- endometrial cancer

- fibroid malignant transformation

Uterine fibroids, also known as uterine leiomyomas, are benign smooth muscle tumors of the uterus with unclear precise causes [1]. They are among the most common gynecological conditions, affecting 20–40% of women globally [2]. In the United States alone, nearly 11 million women are diagnosed with fibroids, with an increased prevalence among African American women [3]. A study has reported that the prevalence can reach 33.9% in certain populations, especially among women who have not yet given birth [4].

Although benign, uterine fibroids can significantly affect a woman’s quality of life by causing heavy menstrual bleeding, pelvic pain, urinary frequency, constipation, and infertility [5]. Approximately 70–75% of women with fibroids experience these symptoms [5]. Fibroids are the leading cause of hysterectomy, emphasizing their severe effects on reproductive health [6]. During pregnancy, fibroids are present in 1–10% of cases, with complications occurring in 10–40% of cases [7].

The exact cause of uterine fibroids remains unknown, but several factors contribute to their development, including genetic predisposition, hormonal influences (estrogen and progesterone), epigenetic modifications, and inflammation [8]. Women with a family history of fibroids, a high body mass index (BMI), and elevated estrogen levels are at an increased risk [9]. Additionally, environmental factors such as early menarche, nulliparity, and exposure to endocrine disruptors may also contribute to fibroid formation [10].

Understanding the epidemiology of fibroids, including their common diagnosis through clinical evaluation and ultrasonography, provides a foundation for discussing treatment options [11]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides detailed visualization and is used to assess fibroid size, location, and characteristics in complex cases [12]. In some instances, histopathological examination is required to differentiate fibroids from malignant tumors such as leiomyosarcoma [13].

These treatments, tailored to symptoms, size, and location, include: (i) medical therapy, hormonal treatments such as gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists, and selective progesterone receptor modulators (SPRMs) help reduce fibroid size and symptoms [14, 15]. (ii) Minimally invasive procedures such as uterine artery embolization (UAE), high-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), and MRI-guided focused ultrasound surgery (MRgFUS) are emerging as effective nonsurgical alternatives [11]. (iii) Surgical intervention: myomectomy is preferred in women who wish to preserve fertility, whereas hysterectomy remains the definitive treatment in severe cases [16].

Uterine fibroids significantly affect women’s health, particularly those aged 35–39 [17]. The most common symptoms were irregular menstrual bleeding, pelvic pressure, and infertility [18]. In some cases, fibroids contribute to pregnancy complications, menstrual disturbances, and chronic pelvic pain [19].

The management of fibroids involves a combination of medical, surgical, and minimally invasive treatments. SPRMs and low-dose mifepristone have shown effectiveness in reducing symptoms [14, 15]. Modern imaging techniques such as MRI and transvaginal ultrasound play a crucial role in diagnosis and treatment planning [20, 21].

Fibroids can also affect fertility, alter the uterine environment, and affect implantation success in assisted reproductive technologies [22]. Furthermore, their association with other benign gynecological conditions and cancers underscores the need for early detection and personalized treatment strategies [1].

Beyond physical symptoms, fibroids can significantly affect quality of life, leading to pain, fatigue, emotional distress, and limitations in daily activities [23, 24]. Psychological effects, including stress, anxiety, and reduced sexual well-being, further highlight the importance of comprehensive patient care [25, 26].

Timely diagnosis and evidence-based treatment are essential for mitigating fibroid-related complications. With a range of available pharmacological, interventional, and surgical options, personalized management strategies can help improve health outcomes and overall well-being [27, 28].

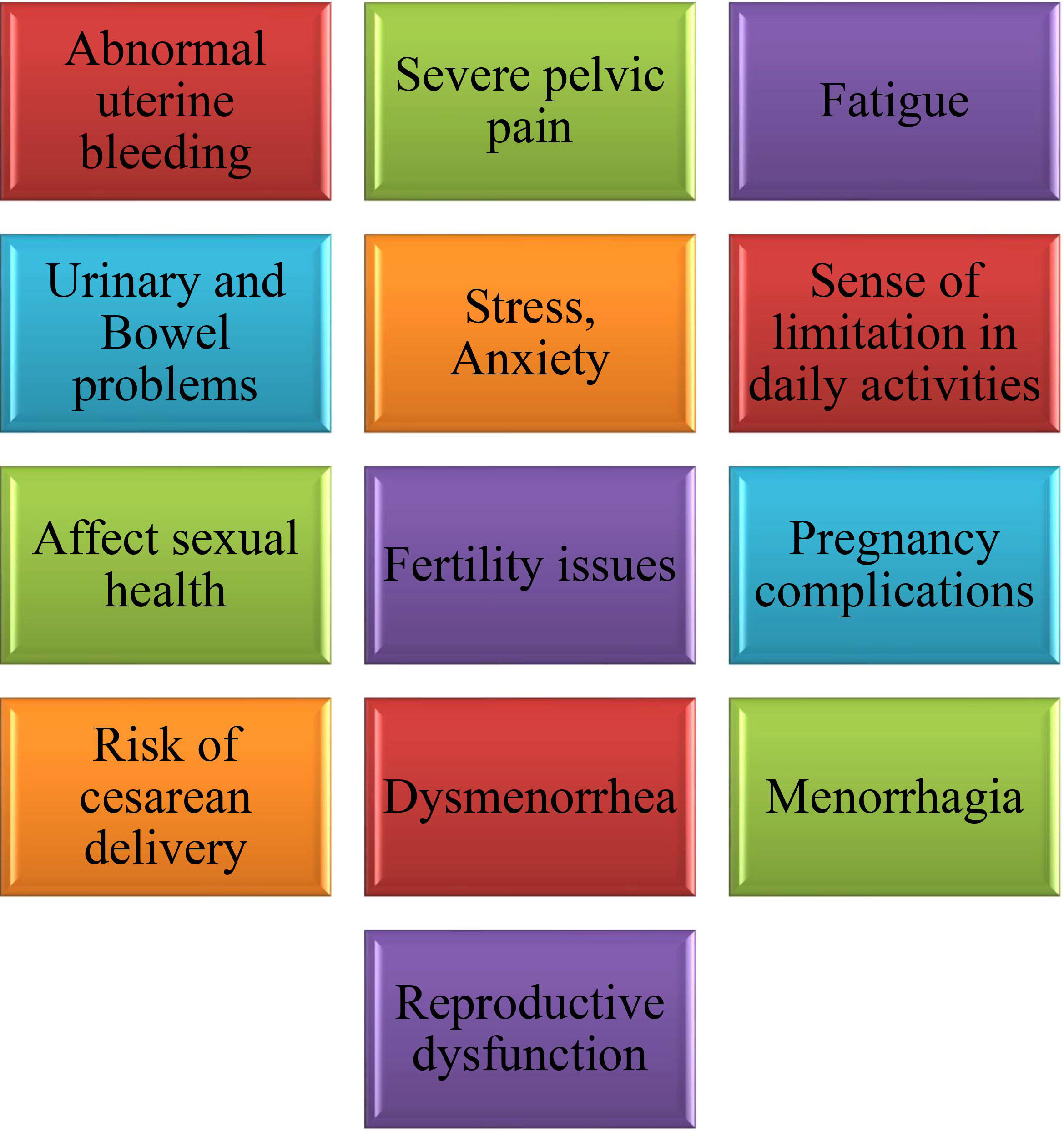

The effect on women’s health may be substantial because of the wide variety of clinical presentations that comprise common symptoms and problems of uterine fibroids. Depending on the variables, including the size and location of the uterine fibroids, one may encounter a variety of symptoms. Discomfort in the pelvis, heavy or painful periods, an increase in the frequency with which one needs to urinate, and problems with reproduction, such as infertility, problems during pregnancy, or miscarriage, are common symptoms [29, 30, 31]. Medical intervention may be necessary if complications related to uterine fibroids progress to critical stages. Urinary retention, hydronephrosis due to obstructive uropathy, sarcomatous alterations (infrequent instances), hyaline or red degeneration of fibroids, and severe anemia requiring blood transfusions are some of the consequences of uterine fibroids [32]. Fibroids, in addition to the difficulties associated with pregnancy, also represent hazards to newborn health and obstetric issues. These complications include fetal malposition, premature delivery, placenta previa, postpartum hemorrhage, and neonatal morbidity [33, 34]. Physical pain, mental anguish, and limitations in everyday activities that may result from uterine fibroids include excessive menstrual flow, abnormal uterine hemorrhage, infertility, lower abdominal pain, iron-deficiency anemia, and other related conditions. Fibroids may affect a person’s general health in addition to their bulk symptoms, including abdominal fullness, constipation, and increased urine frequency. The aforementioned information is summarized in Fig. 1 for further clarity.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

A simplified diagram of the clinically important symptoms of fibroids.

Recent research has highlighted a strong genetic and epigenetic link between uterine fibroids and malignancies, particularly leiomyosarcoma and endometrial cancer [35, 36, 37]. Several gene mutations have been implicated in the development and malignant transformation of fibroids. Mediator complex subunit 12 (MED12) mutations, found in up to 70% of fibroids, are also frequently detected in leiomyosarcomas, suggesting a shared tumorigenic pathway [38, 39]. Additionally, mutations in HMGA2, COL4A5-A6, and FH are associated with fibroid growth and may contribute to cancer susceptibility [40, 41]. FH mutations are linked to hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC), reinforcing the genetic overlap between fibroids and malignancy [42].

Both fibroids and many gynecological cancers exhibit common changes in DNA

methylation and histone modification patterns, which can affect gene expression

[36, 43]. Hypermethylation of tumor suppressor genes and hypomethylation of

oncogenes contribute to fibroid growth and may facilitate malignant

transformation [36]. Additionally, silencing of key apoptotic and cell cycle

regulatory genes through epigenetic mechanisms has been linked to tumor

progression [37]. Dysregulation of microRNAs (miRNAs) plays a crucial role in

fibroid progression and is potentially associated with malignancy. Specific

miRNAs involved in cell proliferation, extracellular matrix remodeling, and

apoptosis have been found to be altered in both fibroids and uterine sarcomas

[44]. Furthermore, fibroids and gynecological cancers share dysregulation in key

oncogenic pathways such as Wnt/

Although fibroids are typically benign, chromosomal instability and the accumulation of genetic mutations may contribute to their rare but significant malignant transformation [8]. Research indicates that fibroids exhibiting increased genomic alterations have molecular similarities to aggressive uterine sarcomas [47]. This evidence suggests that although uncommon, the potential for malignant progression should not be overlooked.

Understanding the genetic and epigenetic links between fibroids and cancer is essential to identify high-risk individuals, improve early detection, and develop targeted therapies. Further research into molecular markers and genomic instability will help clarify the mechanisms underlying fibroid-associated malignancies [48].

The development of uterine fibroids and their potential malignant transformation

involve multiple hormonal, genetic, and signaling pathways, many of which are

also implicated in cancer progression [49]. Key pathways include estrogen and

progesterone signaling, oncogenic regulators such as HMGA2, and cell

proliferation pathways such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR, Wnt/

Estrogen and progesterone play central roles in the pathogenesis of fibroids by promoting cell proliferation and inhibiting apoptosis [8]. Fibroid tissues contain elevated levels of estrogen receptors (ER) and progesterone receptors (PR), leading to enhanced hormonal responsiveness [56]. This hormone-driven proliferation shares similarities with hormone-sensitive cancers, particularly endometrial and breast cancer [57].

Excessive extracellular matrix (ECM) deposition is a defining characteristic of

fibroids and contributes to tumor stiffness and abnormal tissue growth [54].

Dysregulation of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-

As illustrated in Fig. 2, complex genetic and cellular connections are

highlighted by the molecular landscape of uterine fibroids, which shows that

there are major common pathways involved in cancer formation. Studies have shown

that the Wnt/

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

The molecular landscape of uterine fibroids illustrates shared

potential pathways with cancer development, including the Wnt/

Uterine fibroids are classified on the basis of their location, histological features, and clinical impact. While most fibroids are benign, certain subtypes exhibit genetic and molecular alterations that suggest a potential link to malignancy [60, 61].

Uterine fibroids, the most common benign tumors in women of reproductive age, are classified into distinct types based on their location, each with unique clinical implications that affect symptoms, fertility, and treatment strategies. Submucosal fibroids are located beneath the uterine lining and protrude into the endometrial cavity, often leading to heavy menstrual bleeding and fertility complications [17]. Their proximity to the endometrium has raised concerns regarding the potential interactions between endometrial hyperplasia and carcinogenesis [62]. Intramural fibroids are found within the uterine muscle, which may distort the uterine cavity and cause pelvic pain, abnormal bleeding, and pregnancy complications [63]. Although typically benign, their growth patterns and genetic features warrant further study regarding malignant potential [64]. Subserosal fibroids are located on the outer uterine surface and exert pressure on the surrounding organs, causing urinary and bowel symptoms, but have minimal reproductive impact [65]. Rare and atypical fibroids including parasitic fibroids, broad ligament fibroids, and giant cervical fibroids exhibit unusual growth patterns that can mimic malignancies, complicating diagnosis [66, 67].

Certain fibroid subtypes exhibit molecular and histopathological features that require careful differentiation from uterine sarcomas. Cellular and atypical fibroids display increased mitotic activity, which can be mistaken for malignant tumors [60]. Fumarate hydratase-deficient (FH-d) fibroids, a rare variant, have been linked to HLRCC, reinforcing a genetic connection with malignancy [68]. Intravascular leiomyomatosis (IVL), although benign, exhibits aggressive growth patterns, occasionally infiltrating blood vessels and mimicking malignancies [69, 70].

While most fibroids are non-cancerous, distinguishing them from uterine sarcomas remains a significant diagnostic challenge [71, 72]. Histopathological examination is the gold standard for ruling out malignancies. Novel molecular markers and imaging techniques are being explored to improve early detection of high-risk fibroid subtypes [73, 74]. Although uterine fibroids are generally benign, certain subtypes share genetic and molecular characteristics with other malignancies. Advances in genetic profiling and biomarker research will enhance risk stratification and guide personalized treatment strategies [75, 76].

Table 1 provides a condensed categorization of uterine fibroids with details of their location, characteristics, symptoms, impact on fertility, and available treatment choices.

| Type of fibroid | Location | Characteristics | Symptoms | Impact on fertility | Treatment options |

| Submucosal fibroid | Beneath inner lining (endometrium) | Protrudes into the uterine cavity | Heavy menstrual bleeding, prolonged periods, fertility issues | Interferes with embryo implantation, increases miscarriage risk | Hysteroscopic myomectomy to improve fertility |

| Intramural fibroid | Within the muscular wall of the uterus | Most common type, can distort the uterine cavity | Pelvic pain, heavy menstrual bleeding, pressure on surrounding organs | May affect fertility by distorting the uterine cavity | Myomectomy for symptomatic cases |

| Subserosal fibroid | Outer surface of the uterus | Less likely to affect fertility, may protrude outward | Pelvic pain, urinary frequency, back pain | Less impact on fertility | Surgical intervention for significant symptoms |

| Parasitic fibroid | Extrauterine, within the peritoneum | Rare, thought to result from surgical resection seeding | Abdominal pain, discomfort, palpable mass in the abdomen | N/A | Surgical removal if symptomatic |

| Abdominal wall fibroid | Arises from the abdominal wall | Rare, generally asymptomatic, may follow surgery | Palpable mass, abdominal discomfort | N/A | Surgical removal if symptomatic |

| Broad ligament fibroid | Broad ligament (supports uterus) | Rare, originates from the broad ligament, may cause pressure symptoms | Pelvic pain, urinary symptoms | N/A | Surgical intervention if causing complications |

| Wandering fibroid | Migrated within pelvis or abdomen | Detaches from the uterus, may migrate | Palpable mass, abdominal pain or discomfort | N/A | Surgical removal if symptomatic |

| Giant cervical fibroid | Cervix | Large fibroids located in the cervix, can cause significant symptoms due to size | Pelvic pressure, urinary frequency, abnormal vaginal bleeding | N/A | Combination of medical therapy and surgical intervention |

| Histological subtypes | Varies | Fibroids with different histological features, such as cellular variants or unusual growth patterns | Symptoms vary depending on subtype | Varies depending on subtype | Histopathological evaluation, specific management strategies |

| Intravascular leiomyomatosis | Blood vessels or lymphatics | Rare, can mimic malignancies | Varies | Requires careful evaluation to rule out malignancy | Histopathological assessment for determining malignancy potential |

N/A, not applicable.

Although uterine fibroids are typically benign and have not been directly linked to an increased risk of uterine or ovarian cancer, research continues to explore their potential associations with other cancers, such as thyroid and breast cancer, owing to shared hormonal factors and the possibility of misdiagnosis. Uterine fibroids are primarily benign; however, distinguishing them from malignant tumors such as leiomyosarcomas remains a clinical challenge. Histopathological analysis plays a crucial role in differentiating benign fibroids from cancerous uterine sarcomas because imaging alone is often insufficient [1]. Although most fibroids do not undergo malignant transformation, a study has indicated that fibroids and certain gynecological malignancies share common genetic risk loci, suggesting potential overlapping molecular pathways [77]. Additionally, hormonal influences, particularly estrogen and progesterone, not only drive fibroid growth but may also contribute to cancer progression by promoting abnormal cell proliferation [78]. Understanding these molecular and hormonal mechanisms is essential for developing targeted screening strategies and improving early detection of malignancies in target patients. The shared risk factors between uterine fibroids and gynecological malignancies, including obesity and hormonal imbalances, suggest a potential underlying connection that warrants further investigation into their association with cancer risk [79]. Uterine fibroids may make detection and treatment more difficult when gynecological malignancies are present. Delays in cancer detection may occur if fibroids obstruct imaging or clinical examinations. Healthcare practitioners should consider these issues when identifying patients with uterine fibroids, healthcare practitioners should consider these problems [80].

The transformation of benign fibroids into malignant tumors is a multifaceted process. Gene mutations play a crucial role in this transformation, with specific alterations, such as those in MED12, potentially causing benign fibroids to become malignant leiomyosarcomas [81, 82]. Hormonal factors are essential for the growth and transformation of uterine fibroids. Estrogen and progesterone are key hormones involved in this process. If there is a hormonal imbalance, fibroids have the potential to develop into malignant tumors owing to disruptions in cell proliferation and differentiation [83].

Uterine sarcomas are one of many cancers with improperly active cellular signaling pathways, including PI3K/AKT/mTOR. Increased cell proliferation, survival, and malignant transformation are caused by deregulation of these pathways in uterine fibroids [84]. Uterine fibroids and gynecological malignancies may have a common etiology, including alterations in miRNA expression patterns. By affecting gene regulation, cell proliferation, and tumor development, altered expression of specific miRNAs may exacerbate the malignant transformation of fibroids [36].

Environmental endocrine disrupters, including phthalates, are potential causes of the development and progression of uterine fibroids. The combination of hereditary and hormonal variables with specific environmental exposures may increase the likelihood of cancer development [85]. Uterine fibroids and gynecological malignancies share several common pathogenic mechanisms, including genetic alterations, inflammatory processes, and hormonal imbalances. These overlapping pathways suggest that disruptions in hormone regulation, particularly those involving estrogen and progesterone, could contribute to both fibroid development and gynecological cancer progression. Therefore, understanding hormonal influences on fibroids and their potential link to malignancies is critical for improving both diagnostic and therapeutic approaches [86].

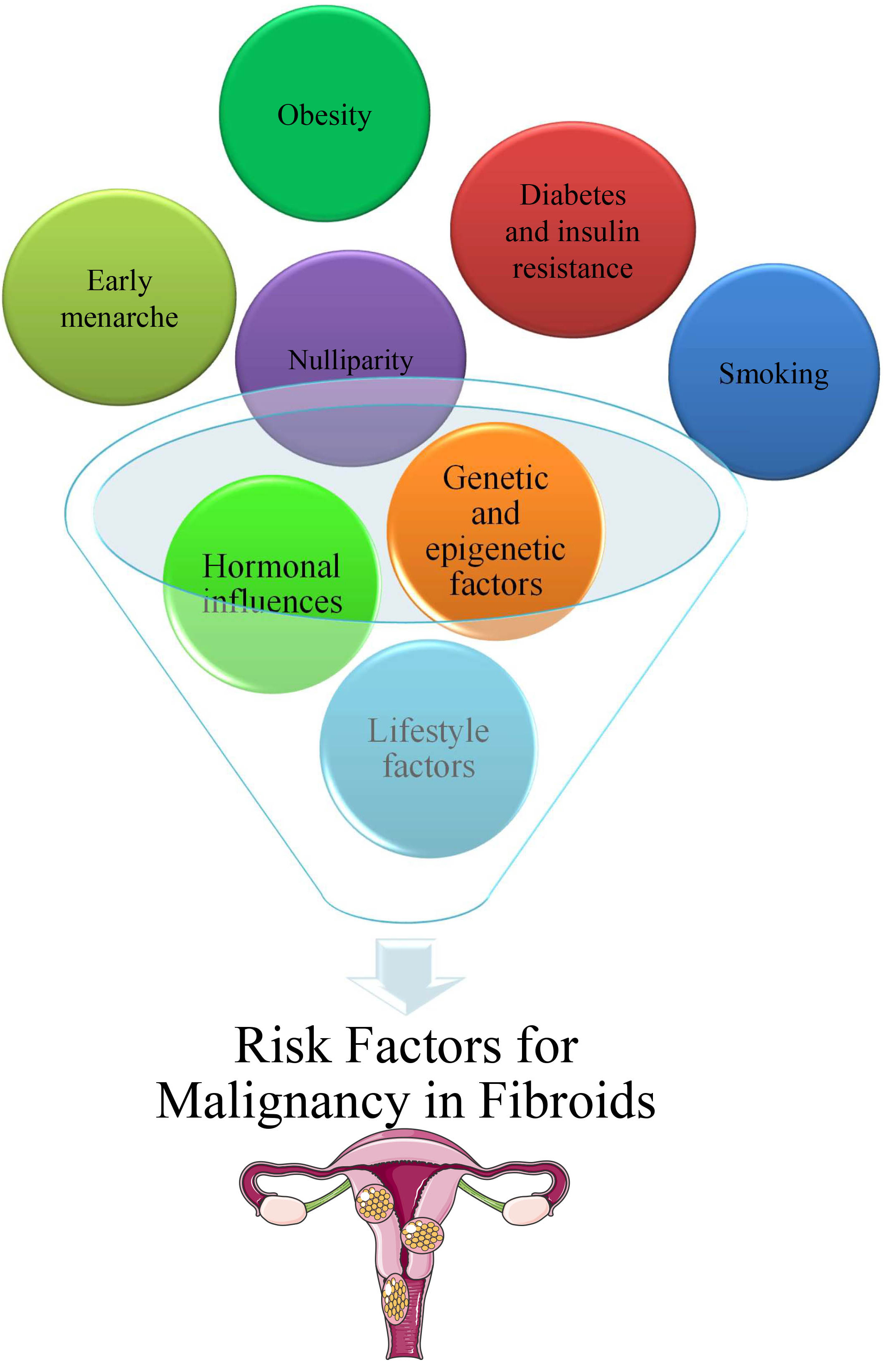

The potential for malignant transformation of uterine fibroids is influenced by multiple risk factors, including genetic predisposition, hormonal imbalances, and lifestyle choices. Understanding these factors is crucial for assessing individual risk profiles and for improving early detection strategies.

Genetic predisposition plays a significant role in the development and progression of fibroids. Studies have indicated that individuals with a family history of fibroids or gynecological malignancies may have a heightened risk of fibroid-related cancers [87, 88]. Additionally, mutations in key genes such as MED12 have been associated with both benign and malignant uterine tumors, suggesting a potential genetic link between fibroid growth and cancer development [81, 82]. Hormonal dysregulation, particularly involving estrogen and progesterone, is strongly linked to fibroid development and possible malignant transformation. Prolonged exposure to elevated levels of these hormones may stimulate abnormal cellular proliferation in the uterus, thereby increasing the risk of fibroid-related malignancies [89, 90]. Furthermore, environmental endocrine disruptors such as phthalates have been implicated in altering hormonal pathways, potentially contributing to fibroid growth and cancer susceptibility [85].

Several modifiable lifestyle factors may affect the risk of developing fibroid malignancy. For instance, obesity is associated with increased estrogen production from adipose tissue, which may promote fibroid growth and influence cancer progression [78, 91]. Additionally, reproductive history, including nulliparity, early menarche, and late menopause, has been linked to prolonged hormonal exposure, further elevating the risk [92]. Other environmental factors such as tobacco use, excessive alcohol consumption, and exposure to endocrine-disrupting chemicals may exacerbate fibroid progression and malignancy potential [93, 94, 95].

Metabolic disorders, including insulin resistance and diabetes, have been correlated with an increased prevalence of uterine fibroids, and may contribute to their malignant transformation [78, 91]. These conditions often create a pro-inflammatory and hyperestrogenic environment, fostering fibroid growth and a complicated disease.

Uterine fibroids may increase or shrink in size due to hormonal shifts that occur during menopause and perimenopause, which are two stages of the aging process. With the changing uterine milieu that accompanies advancing maternal age, the risk of malignancies associated with fibroids increases [96]. The possible risk factors for malignancy in fibroids are shown in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Potential risk factors for malignancy in fibroids.

The association between uterine fibroids and cancer risk involves complex endocrine pathways. Fibroid cells express aromatase, leading to local estrogen production that affects both fibroid growth and the surrounding tissues [97], which can influence the development of hormone-sensitive cancers. This relationship is particularly evident in postmenopausal women, where the presence of fibroids is associated with altered hormone levels, which may contribute to endometrial cancer risk [98]. In obese individuals, increased estrogen production from adipose tissue further complicates this hormonal landscape, potentially elevating the risks for both fibroid growth and hormone-sensitive cancers [99].

Chronic inflammation plays a crucial role in the progression of malignancies.

Uterine fibroids demonstrate elevated levels of inflammatory markers,

particularly tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-

Recent studies have demonstrated important therapeutic implications. While some hormonal therapies, such as GnRH agonists and SPRMs, can effectively manage fibroid symptoms, their long-term effects on cancer risk require further investigation [103]. The relationship between oxidative stress and fibroid formation may also influence cancer risk via molecular mechanisms [104]. These findings have led to increased interest in less invasive treatment approaches, given the potential cancer risks associated with certain surgical interventions [77, 105, 106].

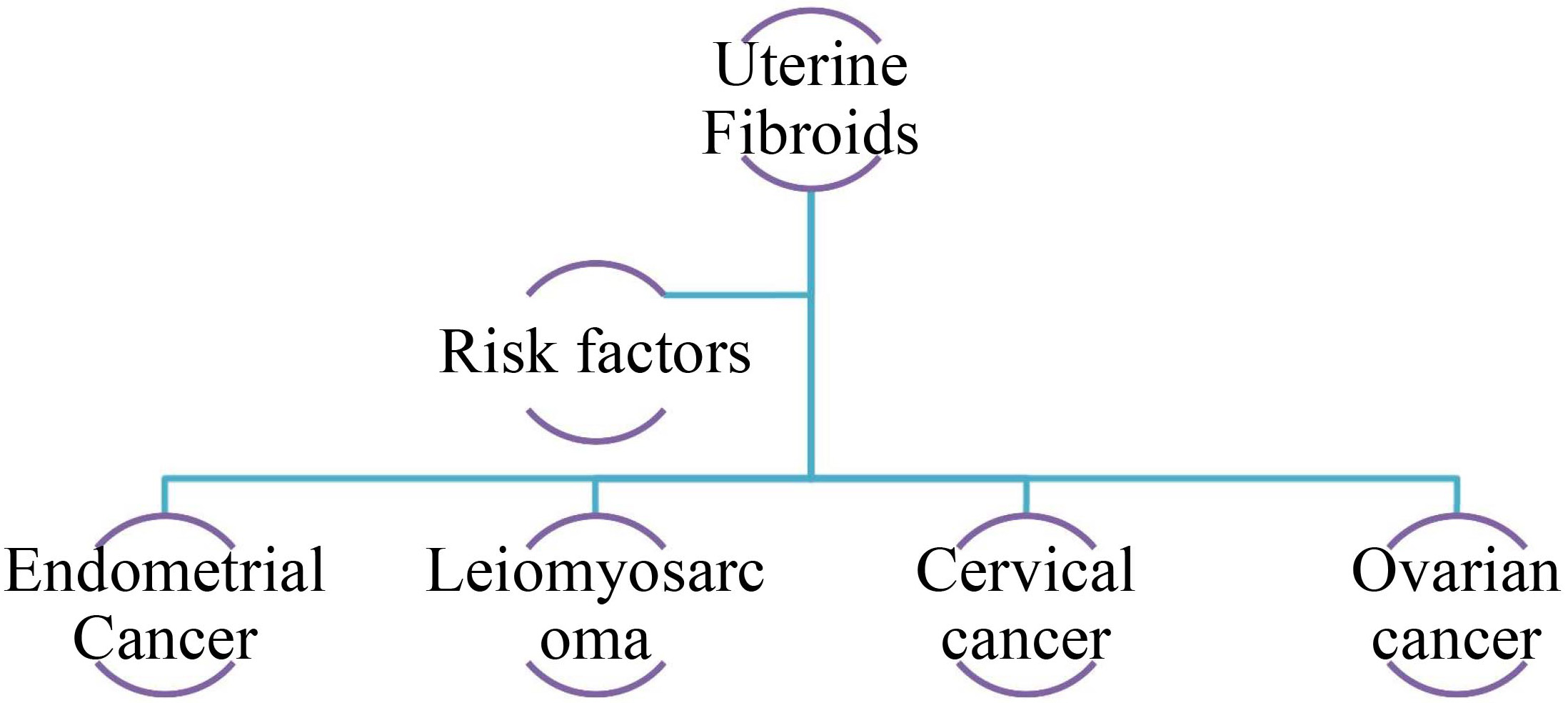

Fig. 4 shows a schematic of the potent cancer types linked to uterine fibroids.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Potential association between different cancer types and uterine fibroids.

Research has examined the relationship between uterine fibroids and endometrial cancer, and some studies have suggested an association. Specifically, a genetic study indicated that women with a history of uterine fibroids may have an increased risk of developing endometrial cancer. However, this relationship remains complex and is influenced by various factors, including hormonal pathways, and potential misdiagnosis. Further investigation is necessary to clarify the nature of this association and its implications for women’s health [77]. Endometrial cancer is common in postmenopausal women having a higher BMI, higher levels of human epididymis protein 4 (HE4) and carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125), coupled fibroids, and thickening endometrial linings, according to research [98]. There may be a correlation between a family history of endometriosis or fibroids and an increased risk of endometrial or ovarian cancer [1]. Although fibroids were once considered harmless lumps, recent genetic research has linked them to changes in endometrial function and endometrial cancer development [77]. Furthermore, it has been shown that fibroids may induce mechanical deformation of the endometrial cavity, which can lead to changes in gamete and embryo transit and subsequent embryo implantation [107].

Research has also shown that fibroids may affect the receptivity and peristalsis of the endometrium, the ability of sperm to migrate, and even the implantation of embryos [108]. In individuals receiving assisted reproductive technologies, fibroids near the endometrium have also been associated with a lower live birth rate [109]. There may be a link between fibroids and endometrial cancer because they cause endometrial damage and make implantation more difficult [110]. Uterine fibroids are characterized by a complex interplay between genetic, hormonal, and environmental variables, which may be summarized as the pathophysiology of the condition. Based on molecular studies, fibroids may modify endometrial receptivity, peristalsis, sperm migration, and embryo implantation [107]. Live birth rates in women with assisted reproductive technologies are lower when fibroids are present near the endometrial cavity [109].

In addition, the presence of fibroids has been associated with changes in the expression of genes in the endometrium, including a reduction in the expression of Homebox (HOX) gene, which may harm reproduction [111]. Fibroids may negatively affect the endometrium because their regulation is abnormal with respect to growth factors and cytokines [112]. Additionally, fibroids have the potential to alter endometrial chemical composition, disrupt inflammatory and autophagy levels, and cause abnormal angiogenesis, all of which may affect endometrial receptivity and function [113]. Research has shown that endometrial fibroid tumors that develop in the uterus as a result of fibroids are associated with an increased risk of endometrial cancer [114]. The similar etiology, clinical features, and pathological parameters of endometrial cancer and uterine fibroids lend credence to the idea that the two diseases are related [1]. The endometrial thickness may be increased by fibroids, affecting fertility [115].

According to genetic studies, endometrial cancer is one of the many cancers that uterine fibroids are associated with. Using Mendelian randomization, Kho et al. [77] showed that uterine fibroids increase the risk of endometrial cancer, demonstrating the significance of genetic variables in gynecological disorders. There seems to be a similar genetic route across many malignancies since Edwards et al. [116] found that genetic variations linked to uterine fibroids were also linked to an elevated risk of glioblastoma and esophageal cancer. In addition, Tai et al. [117] provided more evidence that reproductive characteristics, such as uterine fibroids, are significantly heritable, and that this heritability may extend to cancer risk. Environmental variables such as exposure to heavy metals are also components of this phenomenon [117]. A hormonal link may exist between environmental pollutants, fibroid development, and cancer risk. Johnstone et al. [118] discovered that cadmium levels were correlated with estrogen receptor expression in fibroids. These results highlight the need for ongoing multidisciplinary studies on uterine fibroids and cancer because of the intricate interplay between genetics and environment.

Leiomyosarcoma is a highly uncommon malignant tumor type that develops from abnormalities in the smooth muscle. Although it usually develops independently, there is some evidence that it may, in rare cases, originate from fibroids [119]. Molecular and immunohistochemical techniques have shown that leiomyosarcomas may develop from specific subtypes of leiomyomas, namely the cellular subtype [119]. Although leiomyosarcomas originating from fibroids are relatively rare, they have been reported, particularly in people in their fifth to sixth decades of life [119].

Among hysterectomy specimens from patients older than 60, the incidence of leiomyosarcoma from suspected uterine fibroids may be as high as 1%, with estimates putting the frequency between 0.08% and 0.49% [120, 121]. Although leiomyosarcomas are thought to form from benign fibroids, it is important to consider the possibility of malignant transformation from benign fibroids when older patients present with menorrhagia and suspected uterine fibroids [122]. Leiomyosarcomas are often confused with leiomyomas, making the diagnosis of benign fibroids more difficult. The need for healthcare providers to be more vigilant in preventing the misdiagnosis of leiomyosarcoma as a benign uterine fibroid is highlighted by this diagnostic challenge [123, 124]. Furthermore, it is crucial to obtain a precise diagnosis and handle leiomyosarcoma appropriately to guarantee the best possible results for patients, because it is more aggressive than benign fibroids.

Diagnosis of leiomyosarcoma remains a significant clinical challenge because of its resemblance to benign fibroids. The similarity in imaging characteristics between leiomyosarcomas and fibroids increases the risk of misdiagnosis, potentially leading to delayed treatment and poor patient outcomes [125]. Current imaging techniques, including ultrasonography, often fail to reliably distinguish between the two conditions, and there are no universally accepted diagnostic imaging criteria for leiomyosarcoma [126]. Given its aggressive nature, rapid and accurate identification is crucial to guide appropriate treatment strategies [127]. Accurate and rapid identification of leiomyosarcomas is crucial because of their aggressive nature, as it guides the development of suitable treatment plans, which is a complex process that often requires advanced diagnostic techniques such as immunohistochemistry and molecular profiling to distinguish them from benign conditions such as leiomyomas [128].

A multidisciplinary strategy is necessary for the management of leiomyosarcomas associated with fibroids. The most outstanding prognosis is achieved with surgical resection performed early in the course of leiomyosarcoma, which remains an essential component of cancer management [129, 130]. Conservative treatment options for fibroids must consider the potential dangers of power morcellation in the setting of leiomyosarcoma with serious consideration [131]. Contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS), which contrasts the ultrasound image and surrounding tissue, can also diagnose myometrial and endometrial disorders, including leiomyosarcomas, thus improving minimally invasive treatments [132]. Further investigation into the genetic variations and chromosomal aberrations observed in uterine smooth muscle tumors may lead to the development of diagnostic markers that may differentiate leiomyosarcomas from fibroids [133].

Fibroids may occur in association with ovarian or cervical cancers. Fibroids have been linked to ovarian and cervical malignancies in several studies. Dysregulation of endothelin-1 (ET-1), which is associated with hypertension and reproductive diseases, has been linked to endometriosis, ovarian cancer, and cervical cancer [134]. Possible common causative genes have been identified in shared genetic risk areas for endometrial cancer, endometriosis, and uterine fibroids [77].

While the direct correlation between uterine fibroids and gynecological cancers remains under investigation, fibroids have been associated with systemic health conditions such as cardiovascular disease and adverse pregnancy outcomes [135, 136, 137]. The shared underlying mechanisms, including chronic inflammation, hormonal imbalances, and metabolic dysregulation, may contribute to the increased risk of both fibroid-related complications and malignancies. Additionally, the presence of endometrial polyps alongside fibroids further complicates the gynecological landscape, as polyps themselves have been linked to an increased risk of endometrial cancer. These interconnected factors suggest that while fibroids are benign, their broader systemic effects could influence cancer susceptibility, warranting further research on their potential oncogenic pathways.

Recent years have seen a plethora of research on cervical cancer and its possible molecular underpinnings, particularly regarding tyrosine phosphoproteomes and estrogen receptor 1 (ER1) mutations [138, 139]. A possible biomarker for disease progression, high sialic acid binding Ig like lectin 9 (SIGLEC9) expression in cervical cancer, has been linked to immune cell infiltration [140]. Increasing research points to cervical cancer screening as an effective method for lowering both the incidence and death rates associated with this disease [141].

According to previous studies, there is a strong link between thyroid disorders and uterine fibroids. Additionally, evidence suggests a greater likelihood of thyroid nodules and cancer. Using data from a nationwide health insurance database, Yuk and Kim [142] discovered that fibroid patients had an increased risk of thyroid cancer due to the prevalence of thyroid nodules. Their earlier finding that fibroids increase the risk of benign thyroid disorders in women is consistent with this finding [143]. Guenego et al. [144] reported a correlation between uterine fibroids and differentiated thyroid cancer. They also found that surgical removal of a fibroid increased the likelihood of developing thyroid cancer [144]. This was further corroborated by Li et al. [145], who found that premenopausal women with fibroids had an increased incidence of thyroid nodules. Hormonal and inflammatory variables are pivotal in the processes linking fibroids and thyroid carcinoma; however, this is only partly true. While fibroids raise estrogen levels, which may affect thyroid function, their chronic inflammatory state may encourage the formation of thyroid tumors through inflammatory cytokines [146]. Additional investigations into the standard molecular processes between thyroid illness and uterine fibroids are warranted in light of these results, which indicate a complicated interaction between the two.

Owing to standard hormonal and genetic variables, research has shown a strong association between uterine fibroids and the risk of breast cancer. Owing to the heightened estrogen levels shared by both uterine leiomyomas and breast cancer, population-based research in Taiwan discovered that women with both disorders had a significantly increased risk of developing breast cancer [147]. Using a population-based case-control approach, Tseng et al. [148] further supported these results, indicating that fibroids may accelerate breast tissue carcinogenesis by creating an estrogenic environment. Shen et al. [149] reported a disproportionately high risk of breast cancer among women diagnosed with uterine leiomyoma before the age of 30. Notably, hormonal interactions such as progesterone and estrogen are required for the development of both fibroids and breast cancer [150]. Another potential environmental component that increases the risk of breast cancer in women with fibroids is cadmium (Cd) exposure, which has estrogen-like effects [151]. There has to be further investigation into the common molecular pathways between uterine fibroids and breast cancer, since these related studies show how intricately related the two conditions are.

Shen et al. [1] did not find a significant correlation between uterine fibroids and ovarian cancer, suggesting that a direct link remains unconfirmed. However, other studies have indicated potential associations, such as shared genetic risk regions between uterine fibroids and ovarian cancer, as well as overlapping hormonal and inflammatory pathways. These findings suggest that while no definitive causal relationship has been established, further research is needed to explore the potential mechanisms connecting the two conditions [1]. There may be overlapping molecular pathways between endometrial and ovarian malignancies, since Glubb et al. [152] found shared genetic risk areas for both types of cancer. An increased risk of ovarian cancer may be associated with a strong correlation between uterine fibroids and ovarian cysts, as reported by Wu et al. [153]. Ovarian cancer may develop in women with fibroids because of the hormonal milieu that they create. Ovaries and other tissues may be more susceptible to carcinogenesis due to persistent inflammatory processes and elevated estrogen levels in fibroids. The complicated nature of the link between uterine fibroids and ovarian cancer is highlighted by these results, which underscores the need for further study on this topic.

To diagnose fibroids and distinguish them from cancer, various imaging techniques are essential. The location of fibroids relative to other structures and their diagnosis and monitoring are often accomplished via ultrasound, particularly during pregnancy [154]. It is possible to distinguish between benign, malignant, and ambiguous adnexal masses using ultrasound and MRI [155]. One of the most important functions of MRI is to help identify uterine fibroids by revealing their size and location and distinguishing them from other benign and malignant entities such as leiomyosarcoma [156]. In addition, adenomyosis and uterine fibroids may be accurately diagnosed using transvaginal ultrasound with strain elastography, and the findings are similar to those of MRI-based diagnoses [157].

When it comes to relatively simple clinical situations, gray-scale ultrasonography is used for uterine fibroid diagnosis, while MRI is used for more complicated instances [157]. Broad ligament fibroids can be better identified with ultrasound because imaging technology allows visible separation of the tumor from its surrounding components [158]. Because most fibroids do not cause symptoms and are commonly discovered accidentally during regular ultrasound examinations, this diagnostic tool is vital when a woman is expecting a child [159]. When fibroids exhibit unusual symptoms, a combination of MRI and ultrasound may help rule out cancer [160]. HIFU has garnered much attention as a non-invasive treatment for symptomatic fibroids. HIFU is thought to eliminate fibroids by inducing coagulative necrosis in the desired tissue. The need for precise imaging and subsequent pathological confirmation is further underscored by the fact that histological investigation plays a pivotal role in establishing diagnoses, even when degraded leiomyomas imitate cancer.

To better identify and define intracavitary diseases, Doppler ultrasonography is a helpful supplement to B-mode ultrasonography for evaluating uterine malignancies. Improved diagnostic accuracy and patient treatment may be achieved by integrating Doppler ultrasonography into standard practice for women with perimenopausal and postmenopausal hemorrhage, according to Nguyen and Nguyen [161].

To identify possible biomarkers that indicate that fibroids have transformed into malignant tumors, a study has investigated molecular markers that distinguish benign fibroids from leiomyosarcomas. This demonstrates the importance of G-protein coupled receptor 55 (GPR55) expression in cancer development; thus, lowering GPR55 expression in fibroids may prevent leiomyosarcoma [162]. The presence of driver mutations linked to leiomyomas in some leiomyosarcomas raises the possibility of a connection between benign leiomyomas and their malignant progression [163]. In addition, it distinguishes between several forms of uterine smooth muscle tumors, such as leiomyoma, atypical leiomyoma, and leiomyosarcoma, and emphasizes the need to locate biomarkers in order to obtain a correct diagnosis and prognosis [164]. To distinguish benign fibroids from possible cancers, another study has examined the molecular features of fibroids; they have also addressed the rarity of fibroid malignant transformation and the need for precise imaging and diagnostic methods [165]. This has led to the discovery of MED12 variants as possible diagnostic indicators for uterine cancer and benign tumors, providing new information on the molecular mechanisms underlying fibroid transformation [166]. Identifying possible indicators to distinguish uterine leiomyosarcomas from leiomyomas is crucial, and the authors stressed the need for individualized treatment plans based on molecular markers [167]. Researchers have suggested that growth factor signaling may play a role in advancing uterine leiomyomas, which might indicate a connection between the two processes [168].

Histopathological examination is the gold standard for distinguishing benign and malignant uterine fibroids. This method is critical for ensuring accurate diagnosis, guiding therapeutic decisions, and providing optimal postsurgical care [169]. Fibroids are classified into various subtypes based on histopathological characteristics, including common leiomyomas and rare variants, such as mitotically active, cellular, atypical, and myxoid fibroids, some of which may have malignant potential [170]. Precise classification is essential for differentiating benign fibroids from leiomyosarcomas, thereby reducing misdiagnoses that could lead to inappropriate treatment [171]. Histopathology also plays a key role in distinguishing fibroids from other conditions that present similar clinical features, such as gastrointestinal stromal tumors [172]. In cases where fibroids exhibit severe cystic degeneration, histopathological assessment can effectively rule out malignancy [173]. Additionally, intraoperative histological testing is valuable for confirming diagnoses, particularly retroperitoneal fibroids [174]. Given the potential for misclassification of benign and malignant leiomyosarcomas, histopathological evaluation remains indispensable for achieving precise diagnosis and effective treatment planning [175].

Early detection and prevention play a crucial role in reducing the incidence of uterine fibroids and their potential complications. Identifying modifiable risk factors and implementing targeted screening strategies can help mitigate disease progression and improve patient outcomes [176].

Preventive measures include lifestyle modifications, hormonal regulation, and early medical interventions. One study has suggested that vitamin D deficiency may be a risk factor for fibroid development, indicating that maintaining adequate vitamin D levels may be beneficial [176]. Additionally, managing hypertension and cardiovascular risk factors is essential as they have been linked to fibroid progression [177]. Pharmacological approaches, such as GnRH agonists and SPRMs, may help reduce fibroid size and symptoms, potentially lowering long-term risks [178].

Regular gynecological checkups and imaging techniques, including ultrasound and MRI, are essential for early detection and monitoring of fibroid growth [81]. Screening is particularly important for high-risk populations such as women with early menarche, nulliparity, obesity, or a family history of fibroids [176]. Additionally, fibroid screening during pregnancy can help identify patients at risk for adverse obstetric outcomes [11].

Educating patients about fibroid symptoms, risk factors, and treatment options is crucial for early diagnosis and management [179]. Increased health literacy can help patients make informed decisions, improve treatment outcomes, and reduce disparities in care [180]. Awareness programs should emphasize the importance of early medical interventions, particularly for women at higher risk [181, 182].

Although numerous studies have explored the link between uterine fibroids and cancer, critical gaps remain in the understanding of the mechanisms underlying fibroid malignancy risk [183]. Although research has identified genetic mutations, hormonal influences, and inflammatory pathways as key factors, their exact contributions to fibroid transformation require further investigation [184]. One area that requires further exploration is the role of oxidative stress in fibroid development and its potential link to malignancy. Oxidative stress markers have been associated with multiple gynecological disorders; however, their specific impact on fibroid progression remains unclear [184]. Additionally, while fibroids significantly affect women’s quality of life, more research is needed to assess their long-term effects on reproductive health and overall well-being [185]. Another unresolved question concerns the precise cause of the fibroid formation. Although risk factors such as genetic predisposition, hormonal imbalances, and environmental influences have been identified, the underlying mechanisms driving fibroid growth remain partially understood [186, 187]. The role of dietary factors in fibroid pathogenesis and progression remains an emerging area of study [188, 189]. Addressing these knowledge gaps will help to refine preventive strategies, improve diagnostic accuracy, and develop more effective treatments for fibroid-related complications.

Many ideas for future research on uterine fibroids have been proposed, all of which have the potential to further our knowledge of the problem and lead to new treatments. A more thorough investigation of the molecular processes underlying the development and progression of uterine fibroids is necessary to fully explore this promising area. Finally, to end these benign tumors, researchers must understand the complex biochemical processes that lead to their formation. By doing so, they may identify prospective targets for more targeted and accurate treatment [188]. Understanding the effects of uterine fibroids on fertility and pregnancy outcomes is crucial to elucidate their involvement in diminishing endometrial receptivity [108]. Research on the connection between diet and uterine fibroids is a promising new field. By studying the potential effects of dietary components on growth and development, we may find dietary treatments that can improve nutritional status and help prevent or manage fibroids [189]. To better understand the role of vitamin D in the development of uterine fibroids and identify targets for targeted treatment, it may be worthwhile to investigate the immunohistochemical expression of vitamin D receptors in these tumors [190]. New treatment methods and improvements in the medical management of uterine fibroids should be the primary focus of research into potential new medicines. Research into the effectiveness of novel pharmacological treatments, such as SPRMs, may lead to less intrusive methods for treating fibroids [191]. Moreover, the fibroid management area benefits significantly from investigating the feasibility of transcervical radiofrequency and high-intensity focused ultrasound ablation as less-invasive therapeutic techniques for uterine fibroids [192, 193].

The complicated association between uterine fibroids and the risk of developing cancer was investigated in this study. Particular attention has been paid to the conditions associated with cancer, including endometrial cancer, thyroid cancer, ovarian cancer, breast cancer, and leiomyosarcoma. Important discoveries emphasize the complex relationship between hormonal, genetic, and epigenetic variables in the production of fibroids, and their possible involvement in the progression of the disease to cancer. Despite the continued importance of histological analysis and other cutting-edge diagnostic technologies, many questions remain regarding how to distinguish benign from malignant tumors. Future studies should focus on the molecular processes of cancer transformation, the development of more accurate diagnostic tools, and the creation of tailored treatment strategies. Women diagnosed with uterine fibroids will be better cared for clinically as a result of these initiatives and other changes in screening processes and patient education.

BS designed the research study. BS performed the research. BS wrote the manuscript. BS has read and approved the final manuscript. BS has participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The author declares no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used Grammarly and ProWritingAid in order to check spell and grammar. After using these tools, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.