1 Department of Physiology, Faculty of Medicine, Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, 900000 Can Tho, Vietnam

2 Department of Functional Exploration, Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy Hospital, 900000 Can Tho, Vietnam

3 Faculty of Medicine, Nam Can Tho University, 900000 Can Tho, Vietnam

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) levels in the first trimester of pregnancy are important predictors of future obstetric outcomes. This study evaluated the PAPP-A levels in women with threatened miscarriage and assessed their value in the early diagnosis of this condition.

We conducted a retrospective case-control study from June 2020 to December 2020, involving 122 patients: 61 pregnant women with threatened miscarriage (disease group) and 61 healthy pregnant women (control group). All participants were at gestational age of 11–14 weeks. Pregnant women were selected according to specific diagnostic criteria for threatened miscarriage, regardless of any prior bleeding. The two groups were interviewed to collect data on age, number of pregnancies, body mass index (BMI), risk factors for miscarriage, blood pressure, fetal heart rate, and other relevant parameters. Participants also underwent clinical examinations, including ultrasound scans, non-invasive prenatal testing, and rubella antibody testing. Maternal venous blood samples for PAPP-A quantification were collected at 11–14 gestational weeks.

The median PAPP-A concentration was significantly lower in the disease group (0.63 multiples of the median [MoM]) compared to the control group (1.09 MoM), with a p-value < 0.001. Compared to the control group, the disease group exhibited a higher proportion of underweight women (p = 0.024), along with greater gestational age (p = 0.003), crown-rump length (p = 0.005), and nuchal translucency (p = 0.002) values. The PAPP-A levels demonstrated prognostic value in pregnancy, with a cut-off point of 0.8255 MoM for the disease and control groups receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis demonstrated high sensitivity and relatively high specificity, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.789 (p < 0.001).

PAPP-A demonstrates moderate predictive value for threatened miscarriage, with low PAPP-A levels being associated with this condition.

Keywords

- PAPP-A

- threatened miscarriage

- miscarriage

- pregnancy

- first trimester

Abortion is the most common complication of pregnancy and is defined as the expulsion of the fetus from the uterus before the 22nd week of gestation [1, 2]. It occurs most often in the early stages of pregnancy, with around 80% occurring within the first 12 weeks [3, 4]. Vietnam has one of the highest rates of miscarriage in the Southeast Asian region. Approximately 2% to 5% of Vietnamese couples have endured “recurrent abortions”, meaning three or more consecutive abortions [5]. These are distressing statistics since the underlying cause of periodic abortion that might allow early intervention and treatment can only be identified in around 30% of cases [6, 7].

Thorough clinical examinations and contemporary paraclinical tests, particularly those involving specialized biomarkers, have assisted physicians in diagnosing and monitoring pregnancies [8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. However, no definitive laboratory marker has yet been found that reliably predicts the early risk of miscarriage based on initial symptoms.

In 1990, Ruge et al. [13] highlighted the value of pregnancy-associated plasma protein A (PAPP-A) in predicting fetal viability in cases of threatened miscarriage. Low PAPP-A concentrations were found in patients with threatened miscarriage, often weeks before miscarriage, and while the fetus was still alive [13]. Moreover, Patil et al. [14] reported that low PAPP-A levels (

Data on PAPP-A and pregnancy outcomes in lower-middle-income countries are still quite limited. We, therefore, conducted this study to determine the value of PAPP-A for predicting threatened miscarriage in pregnant women from the Vietnamese population. Our primary objective was to quantify and compare PAPP-A levels between a normal healthy group and a threatened miscarriage group in the first trimester of pregnancy. The secondary objective was to assess the predictive value of PAPP-A for the early diagnosis of patients with threatened miscarriage.

This retrospective case-control study was conducted at Nguyen Dinh Chieu Hospital in Ben Tre Province (Mekong Delta, Vietnam) from June 2020 to December 2020. A total of 61 pregnant women diagnosed with threatened miscarriage and 61 healthy pregnant women were included.

Pregnant women who were selected for the control group included those who met all of the following criteria:

• Pregnant women without threatened miscarriage aged under 45 were 11–14 gestational weeks and received regular follow-ups according to their prenatal appointment schedules. • Do not have any of the following: karyotype abnormalities, assisted reproductive technology, viral infections, uterine abnormalities, environmental exposures (localized trauma, chemotherapy drugs, abortifacient medication, and narcotics), or pre-11-week vaginal bleeding.

The disease group included individuals who were diagnosed with threatened miscarriage during the 11–14 gestational week period based on clinical features and imaging (ultrasound). For this retrospective case-control study, the control group was matched to the disease group concerning age, body mass index (BMI), maternal body weight, maternal body height, unhealthy habits, medical history, and maternal blood pressure.

The sample size was based on the study by Kaijomaa et al. [15], who reported 9 stillbirths (0.9%) among 961 patients with low PAPP-A, but none in 961 women from the control group. The following formula was used to calculate the sample size:

In this formula, n is the total number of miscarriage women;

Besides time in set sampling, pregnant women in the control group are often matched for each case concerning important confounding factors regarding age, weight, height, BMI, smoking status, maternal blood pressure, and heart rate. The sample size ratio in the disease group and the control group is 1:1 in a pair-matched case-control study, with both groups selected from pregnant women who visited the obstetrics clinic of Nguyen Dinh Chieu Hospital. Statistical comparisons, including the Chi-square test, Fisher’s exact test, Student’s t-test, and Mann-Whitney U test, were used to assess the differences between the disease and control groups.

According to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, threatened miscarriage is defined as a nonviable intrauterine pregnancy that may involve either an empty gestational sac or a gestational sac with an embryo or fetus, but without fetal cardiac activity, occurring within the first 12 weeks and 6 days of gestation and the terms “miscarriage” and “early pregnancy loss” are used interchangeably [17]. Additionally, Bell et al. [18] defined threatened miscarriage as mainly a clinical term used when a pregnant woman presents within the first 20 weeks of gestation with spotting, mild abdominal pain and contractions, and a closed cervical os.

The inclusion criteria are formulated based on the standards of the Ministry of Health (Vietnam) [19] and the Radiopaedia article [18].

Threatened miscarriage presents with at least one of the two symptoms:

• Vaginal bleeding with small amounts of bright red, dark, or black blood and mucus. • Mild lower abdominal pain or dull pelvic ache.

For pregnant women who do not have symptoms such as bleeding or abdominal pain that suggest a threatened miscarriage, Bell et al. [18] presented some ultrasound features that may be suggestive of a poor outcome:

• A Fetal bradycardia (defined as a heart rate • A small mean gestational sac diameter. • A large and calcified yolk sac ( • A small or irregular gestational sac with a Mean Sac Diameter/Crown-Rump Length (MSD/CRL) of • A large subchorionic hemorrhage that occupies more than two-thirds of the gestational sac. • An expanded amniotic sign (indicating an abnormally enlarged amniotic cavity). • An absent or poor decidual reaction.

Pregnant women who were ineligible for the current study included those with at least one of the following:

• Women aged 45 years and above. • Karyotype abnormalities: an abnormal or no available non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) result. • Using assisted reproductive technology. • Viral infections. • Uterine abnormalities. • Environmental exposures: localized trauma, chemotherapy drugs, abortifacient medication, and narcotics. • Pre-11-week vaginal bleeding.

Pregnant women were screened with clinical tests such as ultrasound scans, NIPT, and testing for rubella antibodies. Participants underwent all clinical examinations voluntarily, and the results were available before study initiation. Prior to signing the consent forms, the participants were informed about the study details, including the fact that their PAPP-A levels were not used for their pregnancy monitoring.

Information was collected from consenting patients through direct interviews or by reviewing medical records. The data collected for the disease and control groups included general patient information such as age, weight, height, and BMI according to the World Health Organization categorization for Asian adults [20]. Also recorded were risk factors for miscarriage (unhealthy habits and historical factors), blood pressure, gestational age, CRL value, nuchal translucency (NT-value), and fetal heart rate.

PAPP-A concentrations were measured in both the disease and control groups. Venous blood samples were collected from participants, and the plasma samples were stored at –20 °C before quantitative PAPP-A analysis. The samples were thawed only once prior to testing.

PAPP-A levels were measured using an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) on the Cobas PAPP-A platform. The ELISA kit included standards (PAPP-A, Lot Number: 37356201, Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) and a test machine (Cobas 6000, Hitachi-Roche, Tokyo, Japan). The results were reported in mIU/mL, with a measurement range of 0.025–10 mIU/mL and a sensitivity of 0.025 mIU/mL. The final PAPP-A level was measured and converted to the MoM value by dividing the absolute concentration by the median concentration at a specific gestational age and correcting for maternal age.

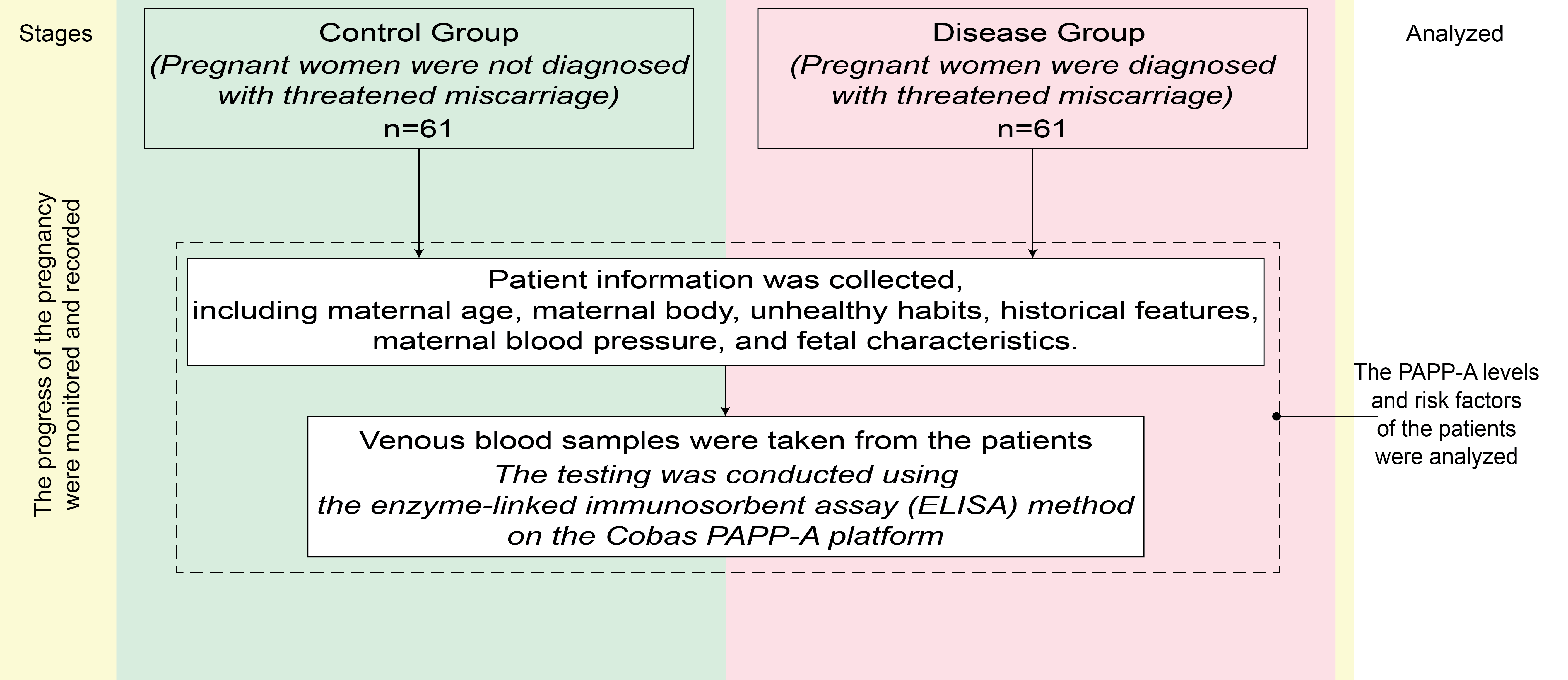

Comparative analysis of the control and disease groups was performed according to the flowchart shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Flowchart of the research steps in this study. PAPP-A, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A.

Data was collected in “.xlsx” format using Microsoft Office Excel software version 16.96.1 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and analysed using SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Qualitative variables were expressed as a frequency and percentage. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine whether a variable had a normal distribution, which was indicated by a p-value

Table 1 shows the characteristics and clinical history of women in the two groups. Most of the pregnant women in this study had a normal or overweight BMI. The disease group contained more underweight women than the control group (p = 0.024), as well as significantly longer gestational age and greater CRL and NT values (p = 0.003, 0.005, and 0.002, respectively). Other characteristics, including maternal age, weight, height, BMI, wine and/or beer consumption, clinical history, blood pressure, and fetal heart rate, were not significantly different between the disease and control groups (p

| Characteristics | Disease groupa (n = 61) | Control groupb (n = 61) | Z-value (Z-test) | p-value | |

| Maternal age | Median age (years) | 29 (20.0–43.0); Q1–Q3: 26.0–35.5 | 29 (19.0–41.0); Q1–Q3: 25.0–34.0 | 0.970 | 0.613* |

| 15 (24.6%) | 11 (18.0%) | N/A | 0.377*# (X = 0.782) | ||

| 46 (75.4%) | 50 (82.0%) | ||||

| Maternal body features | Weight (kg) | 53.0 (40.0–80.0); Q1–Q3: 43.5–57.5 | 53.0 (40.0–75.0); Q1–Q3: 47.0–58.8 | –1.640 | 0.226* |

| Height (cm) | 158.0 (150.0–165.0); Q1–Q3: 154.5–161.0 | 157.0 (150.0–165.0); Q1–Q3: 153.0–162.0 | 0.987 | 0.440* | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 21.1 | 22.0 | N/A | 0.214## (Y = 1.249) | |

| Obese ( | 7 (11.5%) | 12 (19.7%) | N/A | 0.024*# (X = 7.491) | |

| Normal/overweight (18.5–24.9 kg/m2) | 35 (57.4%) | 42 (68.9%) | |||

| Underweight ( | 19 (31.1%) | 7 (11.5%) | |||

| Unhealthy habits | Wine and/or beer consumption | 5 (8.2%) | 3 (4.9%) | N/A | 0.717** |

| No wine and/or beer consumption | 56 (91.8%) | 58 (95.1%) | |||

| Smoking (direct and indirect) | 18 (29.5%) | 9 (14.8%) | N/A | 0.050*# (X = 3.853) | |

| No smoking | 43 (70.5%) | 52 (85.2%) | |||

| Clinical History | Family history of miscarriage (mother, sister, or sister-in-law) | 9 (14.8%) | 4 (6.6%) | N/A | 0.142*# (X = 2.152) |

| No family history of miscarriage | 52 (85.2%) | 57 (93.4%) | |||

| Personal history of miscarriage | 10 (16.4%) | 4 (6.6%) | N/A | 0.133*# (X = 4.029) | |

| Personal history of preeclampsia | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| No personal history | 50 (82.0%) | 57 (93.4%) | |||

| First pregnancy | 46 (75.4%) | 54 (88.5%) | N/A | 0.137*# (X = 3.973) | |

| Second pregnancy | 14 (23.0%) | 7 (11.5%) | |||

| Third pregnancy | 1 (1.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | |||

| Has experienced childbirth# | 6 (9.8%) | 3 (4.9%) | N/A | 0.491** | |

| Has not experienced childbirth | 55 (90.2%) | 58 (95.1%) | |||

| Maternal blood pressure | Systolic (mmHg) | 120.0 (110.0–140.0); Q1–Q3: 120.0–140.0 | 130.0 (110.0–140.0); Q1–Q3: 110.0–140.0 | –0.107 | 0.960* |

| Diastolic (mmHg) | 80.0 (60.0–80.0); Q1–Q3: 60.0–80.0 | 70.0 (60.0–80.0); Q1–Q3: 60.0–80.0 | 1.480 | 0.262* | |

| Fetal characteristics | Gestational age (days) | 90.0 (77.0–97.0); Q1–Q3: 84.0–92.0 | 84.0 (77.0–95.0); Q1–Q3: 81.0–90.0 | 4.306 | 0.003* |

| CRL value (mm) | 65.0 (45.0–80.0); Q1–Q3: 55.0–69.7 | 56.9 (42.0–75.5); Q1–Q3: 49.8–66.3 | 4.179 | 0.005* | |

| NT value (mm) | 1.87 (1.0–2.8); Q1–Q3: 1.5–2.2 | 1.6 (1.0–2.2); Q1–Q3: 1.0–2.2 | 6.283 | 0.002* | |

| Heart rate (beats/min) | 165.0 (125.0–188.0); Q1–Q3: 156.0–175.5 | 157.0 (122.0–187.0); Q1–Q3: 147.0–172.0 | 2.605 | 0.080* | |

| PAPP-A levels (MoM) | 0.63 (0.07–2.59); Q1–Q3: 0.40–0.93 | 1.09 (0.49–2.45); Q1–Q3: 0.87–1.42 | –11.753 | ||

| Multivariable logistic regression | |||||

| S.E. | Wald | p-value | OR (95% CI) | ||

| CRL value (mm) | 0.009 | 0.025 | 0.126 | 0.722 | 1.009 (0.960–1.061) |

| NT value (mm) | 1.302 | 0.623 | 4.370 | 0.037 | 3.678 (1.085–12.473) |

| PAPP-A levels (MoM) | –1.575 | 0.506 | 9.693 | 0.002 | 0.207 (0.077–0.558) |

| Smoking status | –0.904 | 0.538 | 2.821 | 0.093 | 0.405 (0.141–1.163) |

| Underweight | 0.761 | 0.576 | 1.747 | 0.186 | 2.140 (0.692–6.613) |

BMI, body mass index; CRL, crown-rump length; NT, nuchal translucency; Q1, first-quartile value; Q3, third-quartile value; PAPP-A, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A; MoM, multiples of the median; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

#Pregnant women who have had at least one pregnancy with a successful outcome of live birth, regardless of whether they have a history of miscarriage.

*The Mann-Whitney U test was employed, with the variable expressed as median, minimum-maximum, Q1–Q3.

*#Chi-square test and **Fisher’s exact test were employed, with the variable expressed as frequency and percentage.

##The Student’s t-test was employed, with the variable expressed as mean

X and Y represent the Chi-Square value and t-value, respectively.

aThere were 13 miscarriages in the disease group.

bThere were 3 miscarriages in the control group.

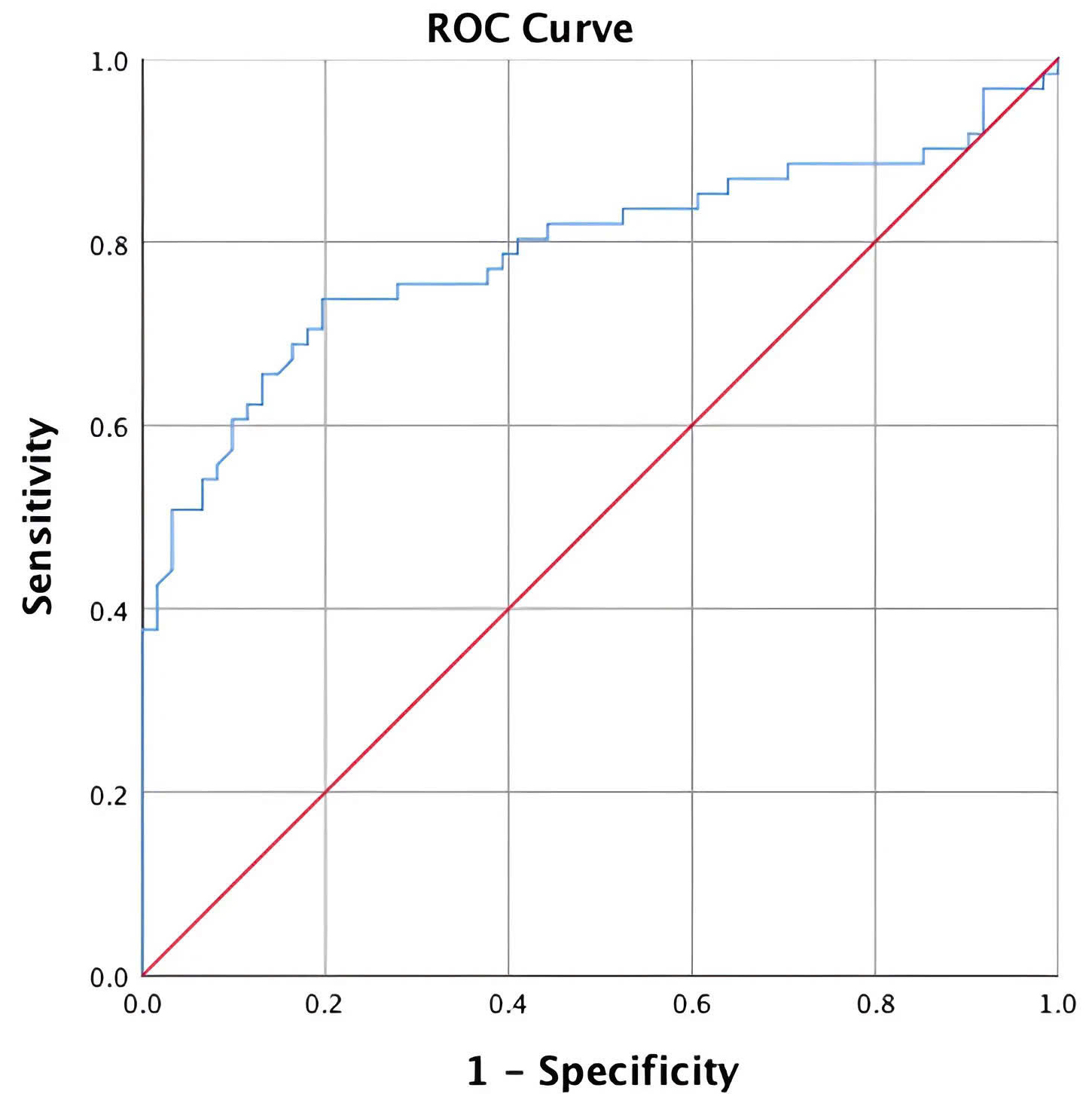

Table 2 shows that the PAPP-A level has moderate predictive value for threatened miscarriage in two groups of pregnant women, with many relevant indexes such as the Youden index, cut-off point, sensitivity, specificity, AUC, and others.

| Classification | Sensitivity (%) | Cut-off point (MoM) | Specificity (%) | Youden index | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | FPR (%) | FNR (%) | AUC (95% CI) |

| p-value | |||||||||

| Disease group and control group (n = 122) | 70.5 | 0.8185 | 80.3 | 0.508 | 78.2 | 73.1 | 19.7 | 29.5 | 0.789 (0.705–0.874) |

| 72.1 | 0.8200 | 80.3 | 0.524 | 78.5 | 74.2 | 19.7 | 27.9 | p | |

| 73.8 | 0.8255 | 80.3 | 0.541 | 78.9 | 75.3 | 19.7 | 26.2 | ||

| 73.8 | 0.8455 | 78.7 | 0.525 | 77.6 | 75.0 | 21.3 | 26.2 | ||

| 73.8 | 0.8635 | 77.0 | 0.508 | 76.2 | 74.6 | 23.0 | 26.2 |

PAPP-A, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A; MoM, multiples of the median; PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; FNR, false negative rate; FPR, false positive rate; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval.

When evaluating the disease and control groups, the optimal cut-off point for MoM of 0.8255 yielded a sensitivity of 73.8% and a specificity of 80.3% (Table 2), with the ROC curve having an AUC of 0.789 (Fig. 2). This indicates the PAPP-A test has moderate value for differentiating between women with and without threatened miscarriage.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. ROC curves and AUC for PAPP-A in the disease and control groups. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the curve; PAPP-A, pregnancy-associated plasma protein A.

The majority of pregnant women in this study were younger than 35 years. Magnus et al. [21] reported that the risk of miscarriage in women aged 45 years and over was more than half. Therefore, only pregnant women aged

Viral infection, particularly human papillomavirus (HPV), was one of the exclusion criteria. Therefore, participants underwent interviews, gynecological examinations, and HPV testing using polymerase chain reaction analysis of cervical fluid to ensure accurate data collection [22].

The gestational age at the time of study participation was slightly higher in the disease group compared to the control group. The disease and control groups were not significantly different in terms of age, BMI, maternal body features, unhealthy habits, clinical history, and maternal blood pressure. This suggests the two groups were appropriately selected and therefore suitable for analysis of PAPP-A concentrations, which was the primary focus of this study. The results are likely to be more robust without interference from confounding variables. However, the disease and control groups showed significant differences in gestational age, CRL, and NT values. Since these differences may affect the PAPP-A value, this biomarker was measured in pregnant women at 11–14 gestational weeks and converted into the MoM to avoid distortion.

A study conducted by Cavoretto et al. [23] showed that the PAPP-A level for in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) was lower in comparison with controls. This confounder and moderator in the PAPP-A level may come from alterations in the placentation of IVF/ICSI pregnancies.

Yaron et al. [24] also found that women with a low PAPP-A level had significantly higher risks of fetal growth restriction and spontaneous miscarriage. It should be noted, however, that the definition of “low” PAPP-A differs between studies, thereby impacting the statistical and clinical significance of the results. Low PAPP-A has been defined as a range or threshold value, including percentages or arbitrary cut-offs ranging from 0.25 MoM to 0.50 MoM.

Using a test with the highest diagnostic accuracy, Swiercz et al. [25] reported a great accuracy for predicting preterm births occurring before 37 weeks of gestation. In comparison, our study found a moderate AUC for the threatened miscarriage group. The calculated cut-off value for PAPP-A in the study by Swiercz et al. [25] did not have satisfactory accuracy for predicting preterm birth occurring before 35 weeks. The best diagnostic accuracy achieved for predicting the preterm premature rupture of membranes (pPROM) was relatively high. Their findings demonstrated that low PAPP-A levels in the first trimester were associated with an increased risk of preterm birth and pPROM before 37 weeks [25]. Additionally, these authors showed that PAPP-A levels during the first trimester were associated with neonatal outcomes such as pH

Jindal et al. [27] reported a significant association between low PAPP-A levels and various adverse pregnancy outcomes, such as intrauterine growth restriction, intrauterine death, pregnancy-induced hypertension, and other pregnancy-related complications.

Hanita et al. [28] found that low PAPP-A in women with threatened miscarriage was associated with pregnancy failure. The median PAPP-A level was significantly lower in patients with miscarriage than in those with successful pregnancies. In the present study, the median PAPP-A level in the disease group was significantly lower than in the control group. Hanita et al. [28] reported the best sensitivity and specificity at a lower cut-off value, while our study achieved the highest sensitivity and specificity at a higher cut-off value.

Movahedi et al. [29] found that the frequency of miscarriage during recent pregnancies in mothers with a low PAPP-A was significantly higher than in mothers with normal or elevated PAPP-A. Moreover, pregnant women with low or normal PAPP-A had a lower BMI than those with higher PAPP-A values.

Sun et al. [30] reported that pregnant women with a history of miscarriage had a higher risk of experiencing premature delivery, gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), placenta abnormality, placenta previa, placenta accreta, and placenta adhesion compared to women with singleton pregnancies and without a history of miscarriage. Yu et al. [31] found that women with a history of induced abortion were more likely to experience preterm births before 37 weeks and 34 weeks [31]. A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies conducted by Woolner et al. [32] revealed that women who had experienced a miscarriage were more likely to report a family history of miscarriage.

Borna et al. [33] reported that PAPP-A values are also correlated with GDM, with GDM cases having a considerably lower PAPP-A level compared to the control group. Women with a low PAPP-A level had a significantly shorter gestational age at delivery, lower birth weight, and higher intrauterine growth restriction. ROC analysis revealed the PAPP-A level was weakly predictive for GDM [33]. Chen et al. [34] found that the PAPP-A level had a value for predicting hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.

Therefore, the current research helps clarify the observed differences in the threshold values. A low maternal serum PAPP-A concentration in the first trimester can predict not only chromosomal abnormalities but also adverse pregnancy outcomes.

Despite producing novel insights, this study had only limited ability to comprehensively assess the predictive value of PAPP-A for the early diagnosis of threatened miscarriage. Our analysis was restricted to a single biomarker, PAPP-A, and did not consider the potential utility of a panel of markers or other clinical factors. Moreover, the results of this study about the diagnostic accuracy of PAPP-A may not be generalizable to all clinical settings, as the performance of the test could be influenced by factors such as gestational age and underlying maternal conditions. Further research involving larger, more representative patient cohorts and a broader range of diagnostic approaches is required to more thoroughly evaluate the role of PAPP-A for early identification of threatened miscarriage.

An accurate pregnancy prognosis is crucial to achieving a healthy pregnancy outcome for the mother and fetus. The current study showed that PAPP-A has moderate value in predicting threatened miscarriage, as low PAPP-A levels were associated with these conditions. ROC curve analysis showed excellent sensitivity and reasonably good specificity at a cut-off point of 0.8255 MoM for the threatened miscarriage group, with an AUC of 0.789.

All data reported in this paper are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

TTTT and THN designed the study and were the project administrators. TTTT and HMP performed data curation, investigation, and resource management. THN, HMP, and HHVL were responsible for the methodology, software, and formal analysis. THN, HHVL, and HMB created the tables, while HMP and HHVL created the figures. TTTT, HMP, and THN were responsible for validation and visualization. THN, HHVL, and HMB wrote the original draft and editorial revisions. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was conducted in full compliance with ethical standards. Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Pregnant women under the age of 18 were not included in the study. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee for Biological Research at Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy (Approval No. 182/HDDD-PCT, dated May 28th, 2020) and followed the principles of the 2013 Declaration of Helsinki. All research participants were provided with comprehensive information regarding the purpose of the study and the procedures involved. They voluntarily agreed to participate and collaborate throughout the research process. Participants had the right to refuse participation or to withdraw from the study at any stage without affecting the quality of their medical treatment.

We are very grateful for the efforts and contributions of Can Tho University of Medicine and Pharmacy, and Nam Can Tho University, Vietnam. Moreover, we acknowledge the cooperation of Nguyen Dinh Chieu Hospital, as well as the pregnant women who participated in this study.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.