1 Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Gynecological Oncology Surgery, Konya City Hospital, 42020 Konya, Türkiye

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Division of Perinatology, Necmettin Erbakan University Meram Faculty of Medicine, 42080 Konya, Türkiye

3 Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Konya City Hospital, 42020 Konya, Türkiye

Abstract

Ovarian torsion is a medical emergency caused by ovarian rotation and requires prompt diagnosis and treatment to prevent complications such as ovarian necrosis. In our study, we aimed to predict ovarian torsion by evaluating preoperative neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR) and inflammatory parameters among patients with ovarian cyst and ovarian torsion.

This retrospective study includes 167 patients who underwent surgery for ovarian cysts or ovarian torsion between January 2021 and May 2024 at Konya City Hospital. Clinical characteristics, along with preoperative hematologic and inflammatory parameters, were compared between patients with and without torsion.

There was no significant difference in ovarian cyst size or cyst lateralization between the ovarian cyst and ovarian torsion groups (p = 0.595 and p = 0.932, respectively). Neutrophil percentage, neutrophil count, white blood cell (WBC) count, NPAR, and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) were higher in the ovarian torsion group (n = 83) compared to the ovarian cyst group (n = 84) (all p < 0.01). Lymphocyte count was lower in the ovarian torsion group. Although the systemic immune-inflammation index (SII) was higher in the torsion group, the difference was not statistically significant. A correlation analysis was performed between patient age, ovarian cyst size, and inflammatory parameters in the ovarian torsion group. When the NPAR cut-off was set at 1.66, high sensitivity (80.7%) and specificity (95.2%) were observed for ovarian torsion. The positive predictive value (PPV) was 94.3%, and the negative predictive value (NPV) was 83.3%. The area under the curve (AUC) for NPAR was 0.892 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.837–0.947), indicating strong predictive performance (p = 0.001).

The higher levels of NPAR, NLR, WBC count, neutrophil percentage, and neutrophil count observed in ovarian torsion cases suggest that these parameters may be useful in diagnosing ovarian torsion. In addition, the high sensitivity and specificity values of NPAR highlights its potential for future studies in the diagnosis of ovarian torsion.

Keywords

- ovarian torsion

- neutrophils

- ovarian cysts

Ovarian or adnexal torsion is a condition in which the ovary, fallopian tube, or their supporting ligaments twist around their vascular axis, leading to disrupted blood flow to these anatomical structures [1]. Although it predominantly occurs in women of reproductive age, ovarian torsion can affect individuals of any age and is considered a gynecological emergency. The prevalence of ovarian or adnexal torsion is 2.7%, making it the fifth most common gynecological emergency. Approximately 15% of patients with adnexal torsion present with symptoms during childhood. Among patients undergoing emergency surgery for acute pelvic pain, the incidence of adnexal torsion ranges from 2.5% to 7.4% [2]. If diagnosis and treatment are delayed, this gynecological emergency can result in organ dysfunction or even loss [3]. If left untreated, adnexal torsion can result in necrosis of the adnexa and/or ovary, which may subsequently lead to infection, peritonitis, thrombophlebitis, and organ loss. In the long term, this may result in infertility. Therefore, it is imperative to implement a rapid diagnosis and treatment of torsion to prevent complications and organ loss [4].

The classic presentation includes the sudden onset of abdominal pain and the presence of an adnexal mass [5]. The most common clinical presentation is pelvic pain, with approximately 90% of patients reporting this symptom. Pelvic pain typically manifests suddenly and is of moderate intensity. The second most common presentation is the presence of an adnexal mass. It has been demonstrated that 85% of torsion cases are accompanied by an adnexal mass [6]. In a significant proportion of torsion cases, pelvic pain is accompanied by nausea and vomiting. In particular, vomiting as an accompanying symptom in suspected torsion cases is considered a significant indicator of ovarian torsion [7].

It has been reported that only 38% of patients with adnexal torsion receive a preoperative diagnosis [8]. The reported sensitivity of ultrasound for the diagnosis of ovarian torsion ranges from 46% to 75% [9]. It is important to note that pelvic magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography scanning are not routinely ordered for the diagnosis of adnexal torsion. Despite the development of advanced diagnostic and imaging techniques, the gold standard for diagnosing torsion remains the intraoperative identification of the torsioned adnexa. A number of recent studies have concentrated on the development of laboratory and imaging tests aimed at facilitating rapid patient treatment and supporting the diagnosis of torsion [10, 11]. A plethora of markers, including ischemia-modified albumin, serum D-dimer, heat shock protein-70, pentraxin-3 and C-reactive protein (CRP), have been examined to evaluate their utility in the diagnosis of ovarian torsion. However, no standardized result has been established [12].

The white blood cell (WBC) count is a marker of inflammation within the body. The five types of WBCs are monocytes, lymphocytes, basophils, eosinophils, and neutrophils. Leukocytosis associated with adnexal necrosis, which occurs in 20% to 55% of patients with adnexal torsion, may serve as a supportive indicator in suspected cases of this condition [13]. In a recent study, the preoperative WBC count, neutrophil count and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) have been examined for their association with adnexal torsion [14]. These markers have been observed to exhibit elevated levels in patients with adnexal torsion, with varying degrees of sensitivity [14]. The neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio (NPAR) is currently utilized as a marker for the detection of a systemic inflammatory response in numerous diseases. NPAR is a predictive and prognostic marker that is readily accessible, cost-effective, and employed in numerous diseases with oncological and chronic inflammatory processes. It is calculated from complete blood count (CBC) and albumin parameters [15]. These tests can be accessed in all emergency services. The results can be obtained in a short time, and NPAR can be calculated. The tests do not incur additional examination costs, and no further interventional intervention is required for the patient.

A number of studies have evaluated the preoperative diagnostic value of inflammatory markers for adnexal torsion. However, the results of the study has been variable, with differing success rates in detecting adnexal torsion [14]. The objective of this study is to ascertain whether preoperative NPAR can be employed as an accurate diagnostic tool for torsioned ovarian cysts prior to surgery.

In this study, data from patients who underwent surgical intervention for the treatment of ovarian cysts or ovarian torsion at Konya City Hospital were analyzed retrospectively. Following ethical committee approval from Necmettin Erbakan University Clinical Research Ethics Board (No: 2024/5032), data from patients who underwent surgery for ovarian cysts and ovarian torsion between January 2021 and May 2024 at the training and research hospital were reviewed. All patient data were processed in accordance with the principles outlined in the Helsinki Declaration.

The study comprised patients who presented to the clinic during the specified dates and underwent surgical intervention due to ovarian cysts. The preoperative hemogram and albumin results, as well as intraoperative ovarian cyst characteristics and ovarian cyst torsion status, were obtained for these patients. The diagnosis of ovarian cyst torsion was confirmed through intra-abdominal observation during the operation. The size, position, and torsion status of the ovarian cyst, along with the preoperative hemogram, albumin, and CRP results, were meticulously documented.

Patients with a history of acute and chronic inflammatory diseases, a diagnosis of malignancy, or ongoing pregnancy, which could influence the study outcomes by causing changes in inflammatory markers and laboratory parameters, were excluded from the study. Other gynecological and surgical conditions that can cause acute pelvic pain, such as ruptured ectopic pregnancy and appendicitis, were also excluded from the study to ensure a more accurate assessment of the parameters associated with ovarian cyst torsion.

The patients were classified into two groups: the adnexal torsion group (n = 83) and the simple ovarian cyst group (n = 84). The evaluation included a range of hematological parameters, including WBC count, neutrophil count, neutrophil percentage, lymphocyte count, platelet count, CRP, systemic immune-inflammation index (SII = neutrophils (µL)

IBM SPSS Statistics 26 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was employed to conduct data analysis. The data’s normality was evaluated using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test and histograms. The results are presented as the mean

The median age of patients in the ovarian torsion group was 24 years (range: 10–47 years), which was significantly lower than the median age of 30 years (range: 9–73 years) in the simple ovarian cyst group (p = 0.001). Cyst size was not significantly different between the two groups, with a mean of 6.85

| Variables | Simple ovarian cyst (n = 84) | Ovarian torsion (n = 83) | t/Z/ | p-value | |

| Age (years) | 30 (9–73) | 24 (10–47) | 4248 | 0.001 b | |

| Cyst size (cm) | 6.85 | 7.10 | 0.532 | 0.595 a | |

| Cyst lateralization | Right | 46 (54.8%) | 46 (55.4%) | 0.007 | 0.932 c |

| Left | 38 (45.2%) | 37 (44.6%) | |||

a Independent t-test (mean

| Variables | Simple ovarian cyst (n = 84) | Ovarian torsion (n = 83) | t/Z | p-value |

| Neutrophil percentage (%) | 60.01 (42.3–74.5) | 76.47 (42.5–93.8) | –8.492 | 0.001 b |

| Neutrophil count (×103) | 4.94 (2.49–10.16) | 9.14 (2.8–22.38) | –8.149 | 0.001 b |

| Lymphocyte count (×103) | 2.45 | 1.83 | –4.489 | 0.001 a |

| Platelet count (×103) | 292.39 | 291.94 | –0.035 | 0.972 a |

| Leukocyte count (×103) | 8.10 (4.32–19.06) | 11.62 (1.98–26.18) | –6.717 | 0.001 b |

| Albumin (g/L) | 40.13 | 42.07 | 2.771 | 0.006 a |

a Independent t-test (mean

| Variables | Simple ovarian cyst (n = 84) | Ovarian torsion (n = 83) | Z | p-value |

| CRP (mg/L) | 2.10 (0.00–6.29) | 21.87 (0.00–331.10) | 0.338 | 0.013 a |

| NPAR | 1.50 (1.098–1.85) | 1.82 (1.182–2.51) | –8.754 | 0.001 a |

| SII | 566.9 (236.7–1408.3) | 1596.4 (245.1–7877.3) | –7.346 | 0.001 a |

| NLR | 2.11 (0.977–4.00) | 6.57 (0.95–26.79) | –8.362 | 0.001 a |

a Mann-Whitney U test [median (Min–Max)].

CRP, C-reactive protein; NPAR, neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio; NLR, neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio; SII, systemic immune-inflammation index.

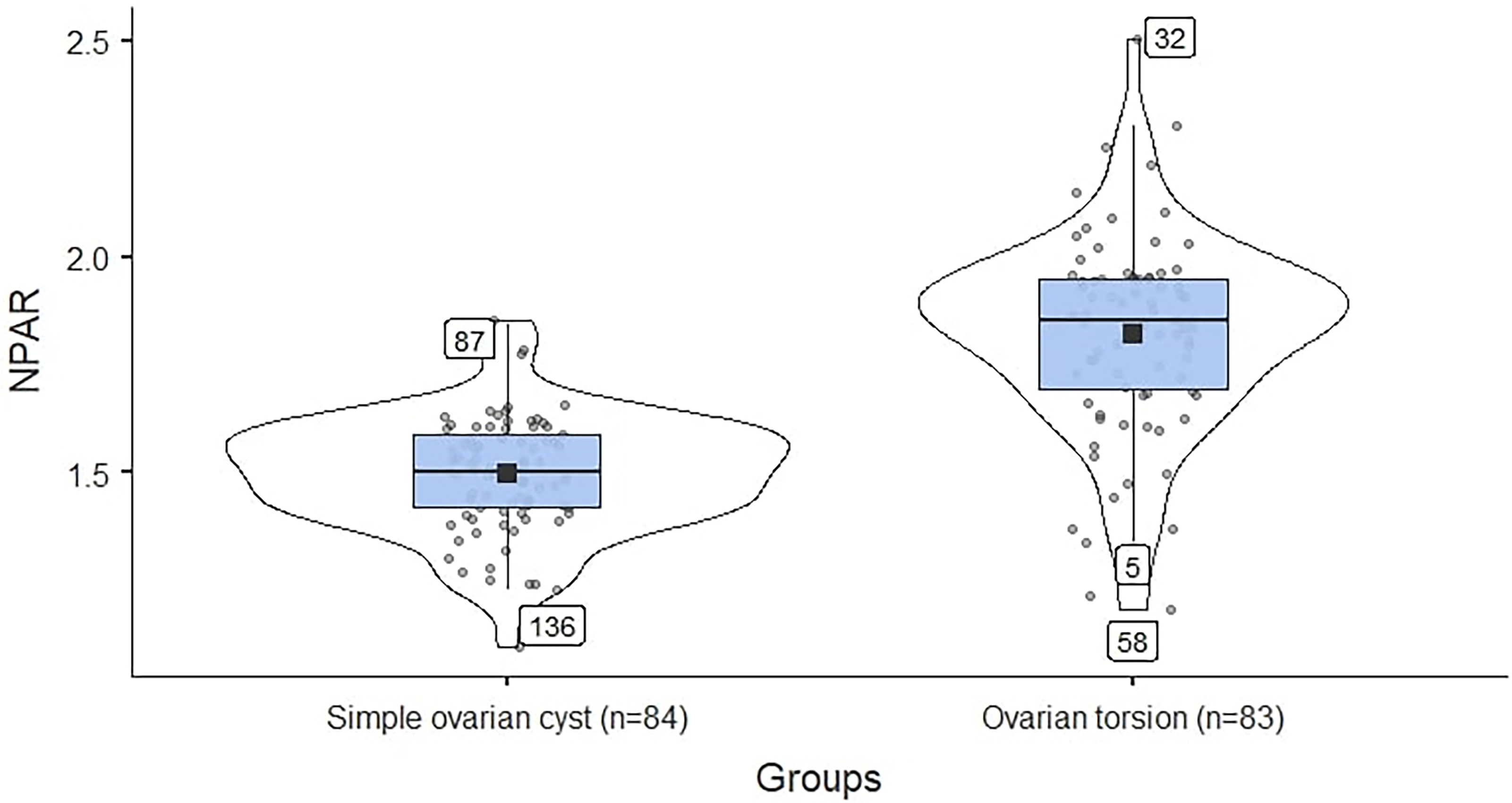

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Comparison of simple ovarian cyst and ovarian torsion groups according to NPAR. The mean value for the ovarian torsion group is higher and exhibits a greater range of variation compared to the ovarian cyst group. NPAR, neutrophil percentage-to-albumin ratio.

The violin plot was employed to visualize the distribution of NPAR results. The mean values and the distribution of deviations from the mean values of the NPAR results in patients with simple ovarian cysts and those with torsional ovarian cysts are shown in Fig. 1. A higher mean value and a wider distribution range were observed in the ovarian torsion group (Fig. 1).

Table 4 shows the correlation analysis of age, cyst size, and inflammatory parameters among all patients. There was a weak but significant positive correlation between age and cyst size (r = 0.165, p = 0.033). Cyst size showed a moderately significant positive correlation with CRP (r = 0.266, p = 0.029). Age had a weak negative correlation with NPAR (r = –0.206, p = 0.008). Among the inflammatory parameters, CRP had a strong positive correlation with SII (r = 0.401, p = 0.001) but a weak positive correlation with NPAR. NPAR exhibited a strong positive correlation with NLR (r = 0.684, p = 0.001). Additionally, SII showed a highly significant positive correlation with NLR (r = 0.899, p = 0.001).

| Age | Cyst size | CRP | NPAR | SII | NLR | ||

| Age | r | 1 | |||||

| p | |||||||

| Cyst size | r | 0.165 | 1 | ||||

| p | 0.033 | ||||||

| CRP | r | –0.008 | 0.266 | 1 | |||

| p | 0.945 | 0.029 | |||||

| NPAR | r | –0.206 | 0.072 | 0.246 | 1 | ||

| p | 0.008 | 0.355 | 0.043 | ||||

| SII | r | –0.142 | 0.188 | 0.401 | 0.619 | 1 | |

| p | 0.068 | 0.015 | 0.001 | 0.001 | |||

| NLR | r | –0.148 | 0.147 | 0.174 | 0.684 | 0.899 | 1 |

| p | 0.057 | 0.058 | 0.156 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

r: correlation coefficient; indicates the direction and strength of the relationship between two variables (ranges from –1 to +1). p

The correlation analysis of age, cyst size, and inflammatory parameters among patients with ovarian torsion is presented. Age did not show a significant correlation with any parameter. Cyst size demonstrated significant positive correlations with CRP (r = 0.288, p = 0.036), SII (r = 0.339, p = 0.002), and NLR (r = 0.266, p = 0.015). Additionally, CRP showed a significant positive correlation with SII (r = 0.370, p = 0.006). NPAR displayed a positive correlation with NLR (r = 0.552, p = 0.001). Moreover, a highly significant positive correlation was observed between SII and NLR (r = 0.863, p = 0.001) (Table 5).

| Age | Cyst size | CRP | NPAR | SII | NLR | ||

| Age | r | 1 | |||||

| p | |||||||

| Cyst size | r | –0.055 | 1 | ||||

| p | 0.621 | ||||||

| CRP | r | 0.047 | 0.288 | 1 | |||

| p | 0.736 | 0.036 | |||||

| NPAR | r | 0.128 | 0.123 | 0.201 | 1 | ||

| p | 0.248 | 0.268 | 0.150 | ||||

| SII | r | 0.067 | 0.339 | 0.370 | 0.490 | 1 | |

| p | 0.549 | 0.002 | 0.006 | 0.001 | |||

| NLR | r | 0.089 | 0.266 | 0.115 | 0.552 | 0.863 | 1 |

| p | 0.423 | 0.015 | 0.414 | 0.001 | 0.001 |

r: correlation coefficient; indicates the direction and strength of the relationship between two variables (ranges from –1 to +1). p

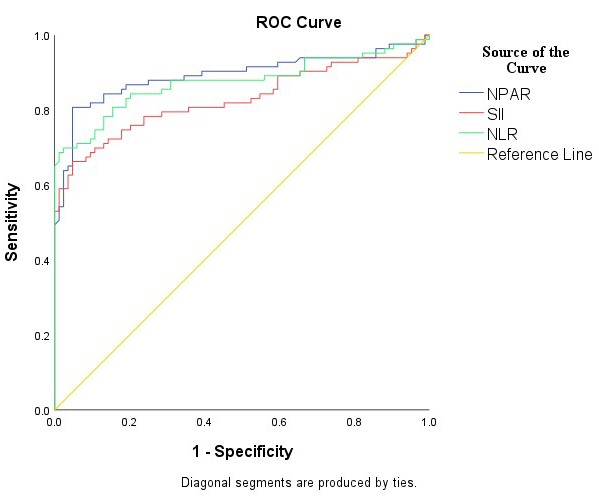

Table 6 and Fig. 2 evaluate the diagnostic performance of NPAR, SII, and NLR in differentiating ovarian torsion from ovarian cysts. NPAR showed a high sensitivity of 80.7% and specificity of 95.2% at a cut-off of 1.66. The PPV was 94.3%, and the NPV was 83.3%. The AUC for NPAR was 0.892 (95% confidence interval (CI): 0.837–0.947), indicating strong predictive performance (p = 0.001). SII demonstrated a sensitivity of 66.2% and a specificity of 95.2% at a cut-off value of 1130.67. The PPV and NPV were 93.2% and 74.0%, respectively. The AUC for SII was 0.829 (95% CI: 0.763–0.896), indicating a strong predictive performance (p = 0.001). The NLR showed a sensitivity of 69.8% and a high specificity of 97.6% at a cut-off of 3.89. The PPV was 96.6% and the NPV was 76.6%. The AUC for the NLR was 0.875 (95% CI: 0.817–0.933), indicating strong predictive performance (p = 0.001).

| Scale | Cut point | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | PPV (%) | NPV (%) | AUC | p-value |

| NPAR | 1.66 | 80.7 | 95.2 | 94.3 | 83.3 | 0.892 (0.837–0.947) | 0.001 |

| SII | 1130.67 | 66.2 | 95.2 | 93.2 | 74.0 | 0.829 (0.763–0.896) | 0.001 |

| NLR | 3.89 | 69.8 | 97.6 | 96.6 | 76.6 | 0.875 (0.817–0.933) | 0.001 |

NPV, negative predictive value; PPV, positive predictive value; AUC, area under the curve.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. ROC analysis of the diagnostic performance of NPAR, SII, and NLR. The diagnostic performance of NPAR, SII, and NLR in differentiating ovarian torsion from ovarian cysts, with the NPAR value situated at a considerable distance from the reference value line. ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

Adnexal torsion is most commonly observed in women of reproductive age and adolescents [16]. Despite the critical importance of early diagnosis and treatment, no biochemical marker for early diagnosis has yet been incorporated into routine clinical practice. In the present study, an evaluation was conducted of alternative markers that could be used in this regard, and a high diagnostic performance result was obtained with NPAR, a marker that has not been previously evaluated in ovarian torsion.

Adnexal torsion is frequently associated with an ovary mass that is enlarged beyond normal size. In studies evaluating the size of torsioned ovarian cysts, Peña et al. [17] found that the average diameter of cysts causing torsion was 5.4 cm, while Rousseau et al. [18] found an average diameter of 7.8 cm. In our study, although the average cyst size was larger in the ovarian torsion group, there was no statistically significant difference in cyst size between the two groups. This is a valuable finding, as it demonstrates that our study was designed to ensure that the comparison between ovarian torsions and ovarian cysts was not influenced by cyst size.

The attachment of the left adnexa to the mesosigmoid makes torsion more frequently observed in the right adnexa. In the existing literature, Warner et al. [19] and Peña et al. [17] reported a similar rate of 71%. Our study yielded a comparable result, with right-sided ovarian cyst torsion occurring in 55% of cases. When comparing the ovarian cyst and ovarian torsion groups, we found that the lateralization of the cysts was similar.

Ovarian torsion is associated with a high inflammatory burden. In response to inflammation, inflammatory markers such as WBC count, neutrophil count, and neutrophil percentage may increase [20]. In a study conducted by Ercan et al. [11], a statistically significant difference in WBC values was reported among patients diagnosed with ovarian torsion (p

The lymphocyte count is a straightforward immunological index that reflects general changes in the immune system. In the study evaluating preoperative lymphocyte counts in patients with adnexal torsion, no diagnostic value was found [22]. However, Lee J et al. [20] and Lee JY et al. [22] reported that the preoperative lymphocyte count was lower in the torsion group compared to the non-torsion group. Similarly, in our study, the lymphocyte count was also found to be statistically significantly lower in the ovarian torsion group.

The SII is a marker that has been demonstrated to be effective in showing acute inflammatory responses in many acute systemic pathologies [23, 24]. It can be calculated using hematologic parameters such as neutrophil count, platelet count, and lymphocyte count. Additionally, it has been found to be significant in predicting the success of methotrexate in ectopic pregnancy [25]. Furthermore, SII has demonstrated diagnostic and prognostic value in various diseases as a powerful biomarker reflecting the inflammatory response. In cardiovascular diseases, high SII levels have been associated with increased mortality and poor prognosis, serving as a risk marker for conditions such as coronary artery disease and stroke [26, 27]. High SII values have been associated with poor prognosis in gynecologic and breast cancers. In particular, it has been associated with reduced overall and disease-free survival in ovarian cancer and triple negative breast cancer [28]. Furthermore, SII has been shown to be a potential marker for predicting the risk of endometriosis, but this association may be influenced by factors such as age, education, and pregnancy history [29]. Consistent with these findings, our study demonstrated significantly higher SII values in patients diagnosed with ovarian torsion compared to those with ovarian cysts. This suggests that SII is a valuable laboratory parameter in distinguishing ovarian torsion and may aid in its early diagnosis.

The NLR, calculated using hematologic parameters such as neutrophil and lymphocyte counts, is widely utilized to assess inflammation severity in various systemic disorders, including cardiovascular diseases, malignancies, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and autoinflammatory diseases [30]. NLR has also been identified as a valuable indicator for several gynecological conditions such as pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, endometrial cancer, cervical cancer, and ovarian cancer [11]. In studies examining the diagnostic utility of NLR in ovarian torsion, it was found that WBC and NLR values were significantly elevated in the ovarian torsion group compared to those with simple cysts [31, 32]. Öksüzoğlu [33] conducted a separate study comparing preoperative hematologic values in 66 patients diagnosed with ovarian torsion and those with simple ovarian cysts, revealing significantly higher mean WBC, neutrophil, and NLR values in the ovarian torsion group. Consistent with these findings, our investigation showed statistically significantly higher mean NLR values in patients diagnosed with ovarian torsion compared to those with ovarian cysts.

To assess the predictive value of NLR, which was found to be elevated in patients with ovarian torsion, Tayyar et al. [34] determined the NLR cut-off value for predicting preoperative ovarian torsion to be 2.9, with an AUC of 0.770. At this cut-off value, the sensitivity and specificity were reported as 73.0% and 79.0%, respectively (p

NPAR has been demonstrated to provide valuable insights by evaluating the ratio of neutrophils to serum albumin levels in inflammatory conditions [35]. Recent studies have identified NPAR as a significant marker in the detection of disease progression involving an increased systemic inflammatory response and ischemia in a range of diseases [15, 36]. Numerous biomarkers have been examined for their importance in the clinical picture of ovarian torsion progressing with inflammatory processes, with the results of these studies then being analyzed [32, 33, 34]. However, there is a paucity of studies on the value of NPAR in ovarian torsion. The present study, therefore, analyzed its diagnostic performance in conjunction with that of other previously investigated markers. In our study comparing ovarian torsion and ovarian cyst groups, NPAR values were significantly higher in the ovarian torsion group. A correlation analysis was conducted to explore the relationship between NPAR and NLR, a parameter that has previously been recognized as significant in ovarian torsion patients. The results revealed a strong positive correlation between NPAR and NLR. In their study evaluating NPAR and NLR concurrently, Ferro et al. [36] also noted that NLR was significantly lower in the group with lower NPAR values, consistent with our findings. As age increases, an elevated NPAR is expected, indicating a decline in albumin levels. However, the observation that NPAR is elevated in the younger age group with documented ovarian torsion further supports this finding.

In pathologies leading to organ ischemia, elevated inflammatory markers may be found due to increased inflammation. Studies have demonstrated that the NLR value, known to rise in myocardial ischemia, also increases in ovarian torsion [23, 37, 38]. In a study conducted on patients with myocardial ischemia, a high NPAR value was identified as a significant predictor of mortality [39]. In our study, an elevated NPAR value was observed in the ovarian torsion group. However, since the duration of torsion, the number of torsions, and the necrosis status of the torsioned ovarian tissue were not evaluated in the current study, it was not possible to assess the relationship between ischemia level and NPAR level.

Numerous studies have been conducted to evaluate the predictive value of inflammatory markers in patients with ovarian torsion. In a retrospective study by Meller et al. [40] examining the performance of NLR in detecting ovarian torsion, the cut-off value was set at 3.5, and the PPV was found to be 82.6%. Another study reported an NLR cut-off value of 3.35, with a sensitivity of 62% and specificity of 86% for torsion [23]. In our study, the NLR cut-off value was determined to be 3.89, exhibiting a sensitivity of 69.8% and a specificity of 97.6% for ovarian torsion.

When the diagnostic performance of the NPAR was evaluated, it demonstrated a high sensitivity of 80.7% and specificity of 95.2% at a cut-off value of 1.66. PPV was 94.3%, and NPV was 83.3%. AUC for NPAR was 0.892 (95% CI: 0.837–0.947), indicating strong predictive performance. Although NPAR demonstrates a markedly superior diagnostic efficacy compared to other markers, no studies in the existing literature have assessed the diagnostic utility of NPAR in the diagnosis of ovarian torsion. Consequently, a comparison could not be made.

With the positive results in our study, NPAR shows promise for future research as a quick and effective parameter that can be measured in the emergency department without additional equipment or costs, making it highly suitable for clinical use. However, our study has some limitations, such as its retrospective nature and modest sample size. The inclusion of patient pain levels and the potential clinical symptoms, including vomiting, was not feasible. Furthermore, the results could not be compared with those of other markers due to the absence of a reference study on this subject. The valuable data obtained for use in the diagnosis of ovarian torsion may lead to prospective studies with larger participation.

In conclusion, these simple and easily accessible preoperative serum markers may be useful in emergency situations when a patient presents to the hospital with acute lower abdominal pain and adnexal torsion is suspected. In our study, NPAR was evaluated alongside previously investigated markers, and it was found to demonstrate superior performance in diagnosing ovarian torsion in patients with ovarian cysts. This study is significant as it is the first to assess the diagnostic performance of NPAR in the context of ovarian torsion, thereby highlighting its clinical utility. The findings of this study pave the way for multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled trials on this topic. Ultimately, this could lead to the introduction of a readily applicable, rapid, and highly accurate diagnostic tool for ovarian torsion into clinical practice.

The raw data from the data search for both the patient and control groups are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

RS designed the research study, performed data collection and management, and contributed to manuscript editing and writing. SO: acquisition and analysis of data for the study; contributed to manuscript editing and protocol development. FA contributed to manuscript editing and data analysis. ECS performed data analysis. OG: significant contributions to the conceptualization or design of the study; developed the research protocol. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was gained from the Necmettin Erbakan University Clinical Research Ethics Board (No: 2024/5032) and all of the participants provided signed informed consent.

We would like to express our gratitude to the management of Konya City Hospital for their invaluable support of the study, as well as for the assistance and guidance provided by their researchers.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.