1 Department of Obstetrics, Dongguan Maternal and Child Health Hospital, 523000 Dongguan, Guangdong, China

2 Department of Internal Medicine, Dongguan Maternal & Children Health Hospital, 523000 Dongguan, Guangdong, China

3 Center of Prenatal Center, Dongguan Maternal and Child Health Hospital, 523000 Dongguan, Guangdong, China

4 Key Laboratory for Major Obstetric Diseases of Guangdong Province, the Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, 510150 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Abstract

Abnormal concentrations of maternal thyroid hormones are risk factors for certain obstetrical complications. However, the influence induced by different types of maternal thyroid dysfunction on obstetrical complications and outcomes remains controversial. This study aimed to systematically evaluate the prevalence of distinct thyroid dysfunction subtypes in pregnant women and their specific associations with adverse obstetric outcomes, thereby clarifying clinical management priorities.

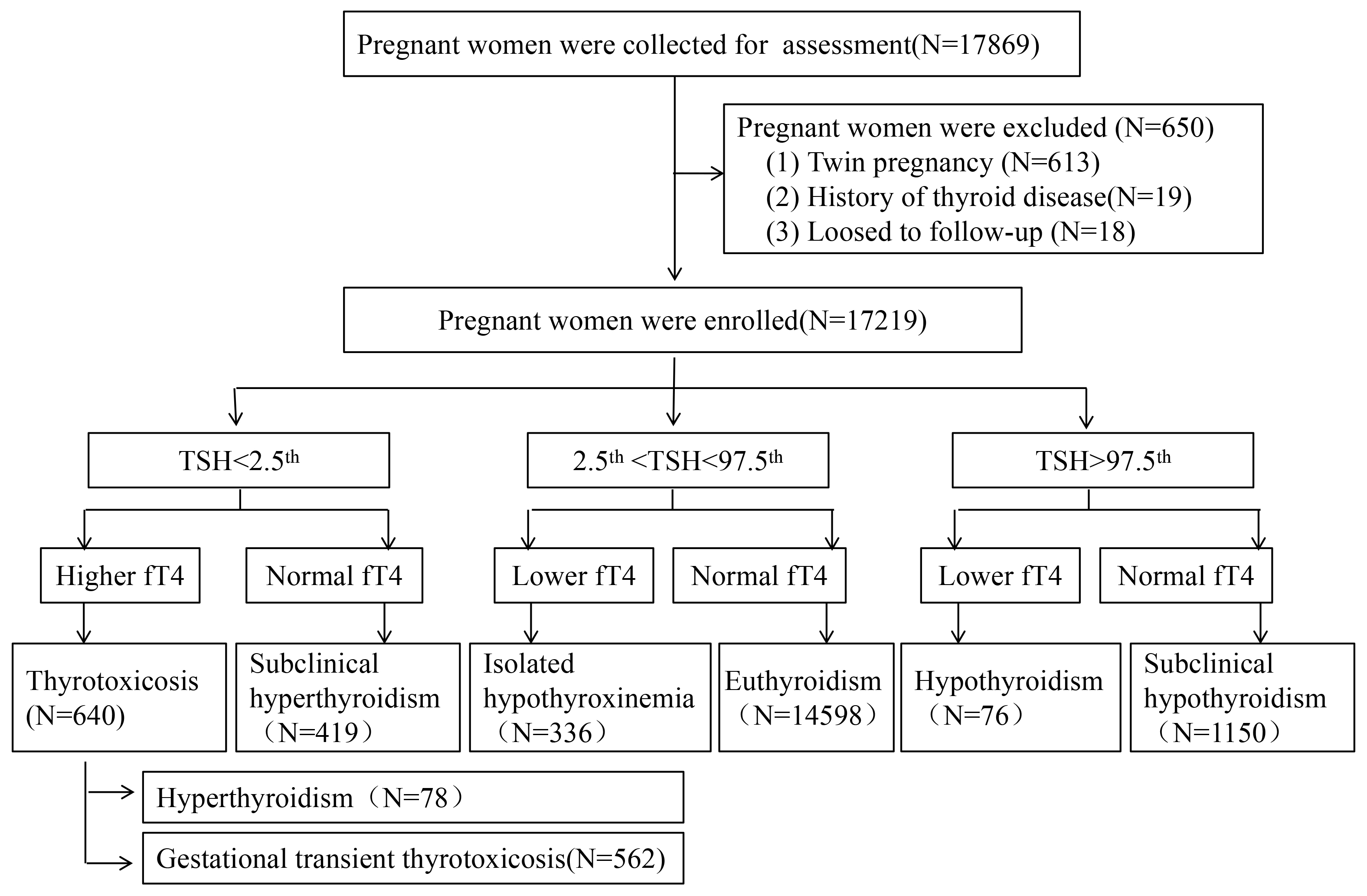

In a retrospective cohort study, a total of 17,219 pregnant women underwent a thyroid function test, including thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and free tetraiodothyronine (fT4). All participants were divided into seven groups based on their blood test results, and their pregnancy outcomes were followed up. The isolated hypothyroxinemia group was divided into two cohorts, depending on whether the patients received levothyroxine. Complications during pregnancy and the outcomes were observed and analyzed in both cohorts.

A total of 2621 (15.22%) women were identified with an abnormal thyroid function, including 1150 with subclinical hypothyroidism, 562 with gestational transient thyrotoxicosis, 419 with subclinical hyperthyroidism, 336 with isolated hypothyroxinemia, 78 with hyperthyroidism, and 76 with hypothyroidism. After adjusting for maternal characteristics, no significant associations were found between specific hyperthyroidism groups and the risk of pregnancy complications. However, mothers with overt hypothyroidism had nearly a 3-fold increased risk of developing postpartum hemorrhage (odds ratio (OR): 2.76; 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.19–6.38; p = 0.018). Subclinical hypothyroidism was associated with an increased risk of premature membrane rupture (OR: 1.44; 95% CI: 1.25–1.64; p < 0.001) and therapeutic abortion related to fetal anomalies (OR: 2.05; 95% CI: 1.13–3.74; p = 0.019). Additionally, both subclinical hypothyroidism, overt hypothyroidism, and isolated hypothyroxinemia were linked to more than a 2-fold increase in the risk of preeclampsia. Mothers with subclinical hypothyroidism exhibited a lower risk for gestational diabetes mellitus (OR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.57–0.79; p < 0.001), while those with isolated hypothyroxinemia had approximately a 1.5-fold increased risk for gestational diabetes mellitus (OR: 1.41; 95% CI: 1.11–1.80; p = 0.005). There were no significant differences in outcomes between those receiving levothyroxine treatment in the isolated hypothyroxinemia group and those who did not.

Our results showed a high incidence of thyroid dysfunction in pregnant women, with subclinical hypothyroidism being the most common, followed by gestational transient thyrotoxicosis. In general, pregnant women with hypothyroidism presented with a high risk of complications during pregnancy. Isolated hypothyroxinemia in pregnant women is concerning, and levothyroxine treatment did not improve pregnancy outcomes and obstetrical complications.

Keywords

- thyroid dysfunction

- obstetrical complications

- pregnancy outcomes

- levothyroxine

Normal maternal thyroid function is crucial for a normal pregnancy and fetal growth. During pregnancy, maternal thyroid dysfunction induces pregnancy complications and influences fetal development in utero and later in life [1, 2, 3]. According to the levels of thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) and free tetraiodothyronine (fT4), thyroid disorders in pregnancy are classified as subclinical hypothyroidism (SCH), overt hypothyroidism, isolated maternal hypothyroxinemia (IMH), subclinical hyperthyroidism, and thyrotoxicosis [4, 5, 6]. On this basis, thyrotoxicosis can be divided into overt hyperthyroidism and gestational transient thyrotoxicosis (GTT) according to its etiology [5].

Thyroid dysfunction is one of the most common complications of pregnancy. The reported frequencies of various thyroid dysfunctions in pregnancy are varied because of difference between research objectives and methods in previous studies [6, 7, 8, 9]. The influence induced by different types of maternal thyroid dysfunction on pregnancy complications and outcomes is still controversial [5, 10]. For example, a meta-analysis of 18 studies, including 3995 pregnant women with SCH, has found no association between SCH and preeclampsia, preterm birth (PTB) and low birth weight [11], but the other studies have reported SCH increased the risk of PTB, preeclampsia and small for gestational age (SGA) [12, 13]. Therefore, more clinical observation and data are necessary for research.

The effects of IMH on pregnant complications are indeterminate, and there is no consensus on whether they should receive levothyroxine. According to the American Thyroid Association (ATA) pregnancy guidelines in 2017 [6], IMH should not be treated. However, an opposite conclusion was made in the European Thyroid Association (ETA) guidelines for the management of SCH in pregnancy and children [14]. In China, the guidelines neither recommend nor are opposed to treatment with levothyroxine for pregnant women with IMH in early pregnancy [15].

In this study, we performed a survey of the prevalence of thyroid dysfunction in early pregnancy in the local region of southern China. We also analyzed the incidence of obstetrical complications and pregnancy adverse outcomes among different thyroid function groups. In additional, we assessed the effects of levothyroxine replacement on adverse outcomes in pregnant women with IMH.

This retrospective cohort study was conducted through a retrospective analysis at the Dongguan Maternal and Children Health Hospital, a large public tertiary care facility located in Guangdong Province, China. The hospital’s obstetrics and gynecology outpatient clinic see an annual patient volume exceeding 50,000 visits. As part of the routine antenatal care, each pregnant woman underwent screening for thyroid function, utilizing TSH, free tetraiodothyronine (fT4), and thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPO-Ab) testing. This screening approach was deemed cost-effective and in alignment with Chinese clinical guidelines [15]. From January 2018 to March 2020, a total of 17,869 pregnant women were enrolled with the following inclusion criteria: (1) TSH and fT4 were examined during the first trimester of pregnancy and (2) the complete pregnancy examination and delivery were completed in our hospital. Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) women with twin pregnancies, (2) women with a history of thyroid disease and medications, (3) women with pre-gestational comorbidities, such as hypertension, diabetes, (4) women who were lost to follow-up. A total of 17,219 cases were enrolled (Fig. 1). All procedures involved in this study complied with the ethical standards of the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and its later amendments. The ethics committees of the Dongguan maternal and Children Health Hospital granted Ethical approval for this study (No. 202133). All participants had signed informed consent.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The flow chart and classification for the process of the subjects selected. TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone; fT4, free tetraiodothyronine.

All participants underwent fasting serum measurements of TSH and fT4 levels in the morning, using an electrochemiluminescence immunoassay with a Cobas Elecsys 601 system (Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). According to the gestational age-specific reference intervals for serum thyroid hormone levels in the Chinese population [16], in the first trimester of pregnancy, the reference intervals for TSH were 0.09 to 4.52 mIU/L and fT4 were 13.15 to 20.78 pmol/L. Pregnant women with abnormal TSH were tested for antithyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb) and thyroid stimulating hormone receptor antibody (TRAb) using an electro-chemiluminescence immunoassay with a Cobas Elecsys 601 system (e 601, Roche Diagnostics, Basel, Switzerland). Reference intervals for TPOAb were 0–35 mIU/L, while reference intervals for TRAb were 0–1.75 mIU/L.

All participants were divided into 7 groups: (1) Overt hypothyroidism was defined as a TSH level higher than the normal reference range and fT4 level lower than the normal range; (2) SCH was defined as TSH level higher the than normal reference range with the normal fT4 range; (3) IMH was defined as normal TSH in combination with a fT4 level lower than the normal range; (4) Subclinical hyperthyroidism was defined as a lower than normal TSH value with a normal fT4 value; (5) Overt hyperthyroidism was defined as TPOAb or TRAb positive thyrotoxicosis; (6) GTT was defined as TPOAb or TRAb negative thyrotoxicosis; (7) Euthyroidism was defined as a normal concentration of TSH and fT4. The patients with overt hyperthyroidism, overt hypothyroidism and SCH were treated with levothyroxine as soon as they were diagnosed. Levothyroxine was used in the patients with IMH according to their wishes.

All of the participants received tests for serum TSH and fT4 during the first trimester of pregnancy, and completed all examinations and treatments needed for pregnancy in our hospital. Data from pregnant women (maternal age, educational level, parity, gestational age at delivery, mode of delivery), complications and outcomes were collected via inpatient and outpatient medical records. Gestational age was evaluated by early ultrasound, and all pregnancy complications and fetal outcomes were diagnosed according to indicators, such as preeclampsia, postpartum hemorrhage (PPH), gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM), premature rupture of membranes (PROM) and the Apgar score of the newborn.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 22.0 version (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive variables were expressed as median (Q1-Q3) for non-normally distributed data and frequency (percentage) for categorical variables. The normality of the data was assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test. The measurement data and numeration data were statistically analyzed with the Mann-Whitney test and Chi-Square test, respectively. Binary logistic regression analysis was applied to evaluate the correlation between thyroid dysfunction and pregnancy complications. Each pregnancy complication was evaluated separately and was adjusted for maternal age, educational level, parity and gestational age at delivery. The results were represented as adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence interval (95% CI). p

The median levels of TSH and fT4, along with the demographics of each group, are presented in Table 1. A total of 2621 pregnancies (15.22%) revealed abnormal thyroid function. The 4 most prevalent types of thyroid dysfunction were SCH (6.68%), GTT (3.26%), subclinical hyperthyroidism (2.43%), and IMH (1.95%). Overt hypothyroidism and overt hyperthyroidism had similarly low incidence rates (0.44% vs. 0.45%). Compared to the euthyroid group, the SCH group had a higher proportion of nulliparous women (32.52% vs. 29.18%, p

| Euthyroid (n = 14,598) | SCH (n = 1150) | Overt hypothyroidism (n = 76) | IMH (n = 336) | Subclinical hyperthyroidism (n = 419) | Overt hyperthyroidism (n = 78) | GTT (n = 562) | ||

| Maternal age (years) | 29 (26–33) | 29 (26–33) | 31 (27–34) | 32 (28–35)** | 30 (27–34) | 29 (26–33) | 30 (27–33) | |

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks) | 39 (38–39) | 39 (38–39) | 39 (37–39) | 38 (37–39) | 39 (38–39) | 38 (37–39) | 39 (38–39) | |

| Parity | ||||||||

| Nullipara (%) | 4260 (29.18) | 374 (32.52)* | 20 (26.32) | 83 (24.70) | 114 (27.21) | 26 (33.33) | 179 (31.85) | |

| Multipara (%) | 10,338 (70.82) | 776 (67.48) | 56 (73.68) | 253 (75.30) | 305 (72.79) | 52 (66.67) | 383 (68.15) | |

| Education level | ||||||||

| High school or lower (%) | 7495 (51.34) | 644 (56.00)** | 40 (52.63) | 182 (54.17) | 148 (35.32)*** | 37 (47.44) | 225 (40.04)*** | |

| Bachelor or higher (%) | 7103 (48.66) | 506 (44.00) | 36 (47.37) | 154 (45.83) | 271 (64.68) | 41 (52.56) | 337 (59.96) | |

| Thyroid function | ||||||||

| fT4 (pmol/L) | 13.91 (12.22–15.86) | 13.65 (12.09–15.47) | 9.62 (8.32–12.03) | 8.97 (8.58–11.96) | 15.21 (13.52–17.42) | 28.53 (22.36–42.77) | 22.23 (18.98–26.52) | |

| TSH (mIU/L) | 2.02 (1.31–2.85) | 5.78 (5.20–8.42) | 6.94 (5.57–14.33) | 2.19 (1.43–3.03) | 0.08 (0.03–0.26) | 0.01 (0.01–0.01) | 0.02 (0.01–0.05) | |

Differences between the euthyroidism and each dysfunction group were compared and significant difference was labeled with*, *: p

SCH, subclinical hypothyroidism; IMH, isolated hypothyroxinemia; GTT, gestational transient thyrotoxicosis.

Multiple complications and pregnancy outcomes were analyzed among 17,219 pregnant women across 7 groups (see Table 2). Overall, there were no significant differences in various complications between each hyperthyroidism group and the euthyroid group. Compared to the euthyroid group, the SCH group exhibited a higher rate of therapeutic abortion related to fetal diseases (1.30% vs. 0.69%, p = 0.019), preeclampsia (6.96% vs. 3.13%, p

| Outcome | SCH (n = 1150) | Overt hypothyroidism (n = 76) | IMH (n = 336) | Euthyroid (n = 14,598) | Subclinical hyperthyroidism (n = 419) | Overt hyperthyroidism (n = 78) | GTT (n = 562) | |

| Spontaneous abortion | N (%) | 12 (1.04) | 2 (2.63) | 12 (3.57) | 195 (1.34) | 8 (1.91) | 1 (1.28) | 7 (1.25) |

| 0.70 | 0.23* | 10.43* | 1.00 | 0.00* | 0.03 | |||

| p | 0.402 | 0.632 | 0.001 | 0.316 | 1.000 | 0.855 | ||

| Premature delivery | N (%) | 96 (8.35) | 10 (13.16) | 47 (13.99) | 1286 (8.81) | 33 (7.88) | 9 (11.54) | 44 (7.83) |

| 0.28 | 1.78 | 10.84 | 0.44 | 0.72 | 0.65 | |||

| p | 0.594 | 0.183 | 0.001 | 0.506 | 0.397 | 0.420 | ||

| Therapeutic abortion related to fetal diseasesa | N (%) | 15 (1.30) | 1 (1.32) | 1 (0.30) | 101 (0.69) | 4 (0.95) | 1 (1.28) | 7 (1.25) |

| 5.47 | # | 0.28* | 0.12* | # | 1.63* | |||

| p | 0.019 | 0.412 | 0.594 | 0.735 | 0.420 | 0.202 | ||

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | N (%) | 185 (16.09) | 11 (14.47) | 105 (31.25) | 3265 (22.37) | 114 (27.21) | 20 (25.64) | 145 (25.80) |

| 24.57 | 2.72 | 14.83 | 5.48 | 0.48 | 3.66 | |||

| p | 0.10 | 0.019 | 0.489 | 0.056 | ||||

| Preeclampsia | N (%) | 80 (6.96) | 7 (9.21) | 29 (8.63) | 457 (3.13) | 10 (2.39) | 3 (3.85) | 14 (2.49) |

| 47.38 | 7.25* | 31.56 | 0.75 | 0.00* | 0.74 | |||

| p | 0.007 | 0.387 | 0.971 | 0.391 | ||||

| Premature rupture of membranes | N (%) | 323 (28.09) | 13 (17.11) | 69 (20.54) | 3088 (21.15) | 85 (20.29) | 15 (19.23) | 110 (19.57) |

| 30.20 | 0.74 | 0.08 | 0.18 | 0.17 | 0.81 | |||

| p | 0.389 | 0.784 | 0.668 | 0.678 | 0.367 | |||

| Postpartum hemorrhage | N (%) | 31 (2.70) | 6 (7.89) | 15 (4.46) | 428 (2.93) | 18 (4.30) | 0 (0.00) | 14 (2.49) |

| 0.21 | 4.87* | 2.68 | 2.63 | 1.43* | 0.37 | |||

| p | 0.647 | 0.027 | 0.102 | 0.105 | 0.231 | 0.542 | ||

| Macrosomia | N (%) | 33 (2.87) | 4 (5.26) | 18 (5.36) | 476 (3.26) | 12 (2.86) | 2 (2.56) | 20 (3.56) |

| 0.52 | 0.43* | 4.51 | 0.20 | 0.00* | 0.15 | |||

| p | 0.470 | 0.512 | 0.034 | 0.652 | 0.979 | 0.697 | ||

| Intrauterine fetal death | N (%) | 3 (0.26) | 1 (1.32) | 0 (0.00) | 23 (0.16) | 1 (0.24) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (0.36) |

| 0.21* | # | # | # | # | # | |||

| p | 0.650 | 0.117 | 1.000 | 0.493 | 1.000 | 0.237 | ||

| Cesarean section | N (%) | 402 (34.96) | 24 (31.58) | 172 (51.19) | 5493 (37.63) | 158 (37.71) | 29 (37.18) | 212 (37.72) |

| 3.25 | 1.18 | 25.66 | 0.00 | 0.01 | 0.00 | |||

| p | 0.071 | 0.278 | 0.973 | 0.935 | 0.964 | |||

| Neonatal asphyxiab | N (%) | 70 (6.09) | 2 (2.63) | 18 (5.36) | 728 (4.99) | 26 (6.21) | 1 (1.28) | 25 (4.45) |

| 2.68 | 0.46* | 0.09 | 1.27 | 1.54* | 0.33 | |||

| p | 0.102 | 0.498 | 0.758 | 0.260 | 0.215 | 0.564 | ||

| Newborn weightc | Mean (kg) | 3.21 | 3.22 | 3.32 | 3.24 | 3.27 | 3.31 | 3.22 |

| t | 2.42 | 0.47 | –3.22 | –1.20 | –1.44 | 1.03 | ||

| p | 0.016 | 0.639 | 0.001 | 0.230 | 0.150 | 0.305 |

a Therapeutic abortion related to fetal diseases, lethal or multiple malformation on ultrasound or chromosome abnormality of the fetus. b Apgar score of newborn less or equal to 7 points. c Cases with spontaneous abortions, premature delivery, therapeutic abortion related to fetal diseases, and intrauterine fetal death were excluded, the sample size of each group after exclusion was: SCH (n = 1024), Overt hypothyroidism (n = 62), IMH (n = 276), Euthyroid (n = 12,993), Subclinical hyperthyroidism (n = 373), Overt hyperthyroidism (n = 67), GTT (n = 502). *Yates’ correction applied. # Fisher’s exact test used.

The results of the multivariate logistic regression analysis examining the correlation between thyroid dysfunction and pregnancy complications are presented in Table 3. After adjusting for maternal characteristics (such as age, educational level, parity, gestational age at delivery), no significant associations were found between specific hyperthyroidism groups and the risks of adverse pregnancy complications.

| Outcome | SCH (n = 1150) | Overt Hypothyroidism (n = 76) | IMH (n = 336) | Subclinical hyperthyroidism (n = 419) | Overt hyperthyroidism (n = 78) | GTT (n = 562) | |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | OR (95% CI) | 0.67 (0.57, 0.79) | 0.52 (0.27, 1.00) | 1.41 (1.11, 1.80) | 1.14 (0.91, 1.43) | 1.17 (0.70, 1.99) | 1.12 (0.92, 1.36) |

| p | 0.051 | 0.005 | 0.244 | 0.548 | 0.281 | ||

| Preeclampsia | OR (95% CI) | 2.31 (1.80, 2.96) | 2.83 (1.28, 6.27) | 2.41 (1.62, 3.59) | 0.73 (0.38, 1.37) | 1.20 (0.38, 3.85) | 0.75 (0.44, 1.29) |

| p | 0.010 | 0.322 | 0.756 | 0.295 | |||

| Spontaneous abortion | OR (95% CI) | 0.51 (0.18, 1.39) | 2.40 (0.06, 91.37) | 1.45 (0.35, 5.99) | 0.73 (0.17, 3.06) | 0.20 (0.01, 3.25) | 0.27 (0.08, 0.87) |

| p | 0.187 | 0.638 | 0.609 | 0.671 | 0.259 | 0.028 | |

| Premature delivery | OR (95% CI) | 0.94 (0.75, 1.17) | 1.40 (0.69, 2.82) | 1.34 (0.96, 1.88) | 0.81 (0.56, 1.18) | 1.28 (0.61, 2.65) | 0.82 (0.59, 1.14) |

| p | 0.562 | 0.349 | 0.085 | 0.278 | 0.515 | 0.239 | |

| Intrauterine fetal death | OR (95% CI) | 1.70 (0.51, 5.72) | 6.64 (0.81, 4.68) | - | 1.36 (0.18, 10.30) | - | 2.02 (0.46, 8.80) |

| p | 0.392 | 0.079 | - | 0.769 | - | 0.349 | |

| Therapeutic abortion related to fetal diseases | OR (95% CI) | 2.05 (1.13, 3.74) | 1.35 (0.15, 12.85) | 0.21 (0.03, 1.56) | 1.11 (0.37, 3.32) | 1.31 (0.14, 12.01) | 1.59 (0.67, 3.74) |

| p | 0.019 | 0.775 | 0.129 | 0.852 | 0.812 | 0.291 | |

| Premature rupture of membranes | OR (95% CI) | 1.44 (1.25, 1.64) | 0.78 (0.43, 1.43) | 0.97 (0.74, 1.27) | 0.95 (0.74, 1.21) | 0.94 (0.54, 1.63) | 0.89 (0.72, 1.10) |

| p | 0.422 | 0.817 | 0.659 | 0.824 | 0.294 | ||

| Postpartum hemorrhage | OR (95% CI) | 0.92 (0.63, 1.32) | 2.76 (1.19, 6.38) | 1.49 (0.88, 2.52) | 1.49 (0.92, 2.42) | - | 0.851 (0.50, 1.46) |

| p | 0.637 | 0.018 | 0.140 | 0.104 | - | 0.557 | |

| Macrosomia | OR (95% CI) | 0.87 (0.61, 1.24) | 1.52 (0.54, 4.24) | 1.58 (0.96, 2.61) | 0.89 (0.49, 1.59) | 0.85 (0.21, 3.50) | 1.15 (0.72, 1.82) |

| p | 0.437 | 0.428 | 0.074 | 0.687 | 0.820 | 0.560 | |

| Cesarean section | OR (95% CI) | 0.901 (0.79, 1.03) | 0.721 (0.44, 1.18) | 1.447 (1.15, 1.81) | 0.917 (0.74, 1.13) | 0.986 (0.61, 1.60) | 0.961 (0.80, 1.15) |

| p | 0.120 | 0.196 | 0.414 | 0.953 | 0.664 | ||

| Neonatal asphyxia | OR (95% CI) | 1.19 (0.93, 1.54) | 0.53 (0.13, 2.16) | 1.07 (0.66, 1.74) | 1.27 (0.85, 1.91) | 0.99 (0.36, 2.73) | 0.87 (0.57, 1.30) |

| p | 0.174 | 0.374 | 0.774 | 0.243 | 0.985 | 0.488 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Both SCH, overt hypothyroidism, and IMH were associated with more than a twofold increase in the risk of preeclampsia. The ORs were 2.31 (95% CI, 1.80–2.96; p

However, women with SCH exhibited a lower risk for GDM (OR, 0.67; 95% CI, 0.57–0.79; p

In the IMH group, 40 out of 336 women received treatment with levothyroxine, maintaining fT4 at normal levels (see Table 4). Notably, the newborn weight in the levothyroxine-treated group was significantly higher compared to the untreated group (3.46

| Complications | Treated gravidas (n = 40) | Untreated gravidas (n = 296) | p-value | |

| Spontaneous abortion | 1 | 11 | 0.000* | 1.000 |

| Premature delivery | 4 | 43 | 0.600 | 0.439 |

| Therapeutic abortion related to fetal diseases | 1 | 0 | # | 0.119 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 13 | 92 | 0.033 | 0.856 |

| Preeclampsia | 3 | 26 | 0.000* | 1.000 |

| Premature rupture of membranes | 9 | 60 | 0.107 | 0.743 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage | 4 | 11 | 1.956* | 0.162 |

| Macrosomia | 2 | 15 | 0.000* | 1.000 |

| Breech presentation | 3 | 20 | 0.000* | 1.000 |

| Neonatal asphyxia | 0 | 1 | # | 1.000 |

| Newborn weighta | 3.46 | 3.30 | –2.169 | 0.031 |

a Cases with spontaneous abortions, premature delivery, therapeutic abortion related to fetal diseases, and intrauterine fetal death were excluded. *Yates’ correction applied. # Fisher’s exact test used, the value in cell is odds ratio.

This study demonstratedthat thyroid dysfunction is a prevalent issue among local pregnant women, with at least 1 in 7 having some form of thyroid dysfunction. While our results are generally consistent with a meta-analysis reporting the prevalence of overt hypothyroidism (0.5%), subclinical hypothyroidism (IMH, 2.05%), and subclinical hyperthyroidism (2.18%) [16], our study revealed a significantly higher prevalence of subclinical hyperthyroidism (SCH, 6.68%) and a lower prevalence of overt hyperthyroidism (0.45%) compared to the meta-analysis (3.47% and 0.91%, respectively). These figures contrast with those reported in Denmark (SCH 5.3%, overt hyperthyroidism 1.6%) [17] and vary across studies conducted in China, with a reported prevalence of SCH and overt hypothyroidism ranging from 0.24% to 8.26% [13, 18]. This discrepancy warrants further investigation. Several factors may contribute to these variations. Differences in iodine intake, although mitigated by China’s universal salt iodization program, could still influence thyroid hormone levels across various regions. Heterogeneity in diagnostic criteria, particularly the threshold values for TSH and free T4 used to define thyroid dysfunction, can significantly impact prevalence estimates. Furthermore, the absence of routine TPOAb testing in our cohort, unlike some other studies, may have influenced our findings, as TPOAb positivity is associated with altered thyroid function and pregnancy outcomes. Future studies should standardize diagnostic criteria and routinely assess TPOAb status to enhance comparability and reduce bias.

We collaboratively determined the prevalence of GTT with endocrinologists to be 3.26%. Differentiating GTT from hyperthyroidism can be challenging and requires consideration of various clinical and laboratory findings [5]. GTT is associated with elevated levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), a hormone secreted by the placenta, and is often characterized by hyperemesis gravidarum, which typically does not necessitate intervention. This condition is a physiological phenomenon rather than an immune disorder, and individuals with GTT typically exhibit negative TRAb test results [19].

In this study, various impacts on adverse pregnancy outcomes among different thyroid dysfunction groups were observed. It is well established that subclinical hyperthyroidism and GTT have minimal adverse effects on pregnancy outcomes and obstetric complications [20, 21], and the present results are consistent with these conclusions. Compared to the euthyroid group, pregnant women with overt hypothyroidism exhibited a higher incidence of preeclampsia and PPH, with nearly a threefold increased risk. However, logistic regression analysis revealed no significant relationship between overt hypothyroidism and other adverse pregnancy outcomes (all p

In Regard to SCH and IMH, the findings suggest that SCH increases the risk of preeclampsia, PROM, and therapeutic abortion due to fetal anomalies, while decreasing the risk of GDM. IMH, conversely, was associated with increased risks of preeclampsia and GDM. These findings are partially consistent with, but also diverge from, previous literature [12, 13, 23, 24, 25, 26], highlighting the potential influence of factors such as timing of levothyroxine initiation, TPOAb status, and gestational age at diagnosis. Liu et al. [13] demonstrated that late-pregnancy SCH is associated with increased risks of preterm birth, preeclampsia, and fetal demise, unlike early-pregnancy SCH.

The data of this study consistently showed an increased risk of preeclampsia across all hypothyroid groups (overt hypothyroidism, SCH, and IMH). This warrants further investigation into the underlying pathophysiological mechanisms. Emerging evidence suggests that hypothyroxinemia interferes with trophoblast migration and the expression of matrix metalloproteinases, both of which are pivotal for placental restructuring and maternal-fetal blood supply, thereby elevating the risk for preeclampsia [27]. Additionally, hypothyroidism is associated with endothelial dysfunction, culminating in compromised vasorelaxation, increased vascular resistance, and the onset of hypertension—pathognomonic features of preeclampsia [28]. Moreover, previous studies have indicated a correlation between elevated levels of soluble fms-like tyrosine kinase 1 (sFlt-1), a pregnancy-specific angiogenic factor central to the pathophysiology of preeclampsia, and increased TSH concentrations, which in turn is associated with an increased risk of SCH [29, 30].

This study identified a 33% reduced OR (0.67, 95% CI: 0.57–0.79) for gestational GDM in women with SCH. This finding aligns with a comparable OR (0.63, 95% CI: 0.50–0.81) reported by Liu et al. [13], as well as trends observed in other studies indicating a decreased incidence of GDM among women with SCH [31, 32]. It has been hypothesized that elevated TSH levels may negatively influence the development and occurrence of GDM by binding to TSH receptors present on extrathyroidal tissues [13].

There is no consensus on treating IMH, and treatment decisions often rely on clinical judgment or patient preference due to a lack of definitive evidence. With an incidence rate of 1.95%, the effectiveness of levothyroxine in IMH must be established. This study found that levothyroxine did not significantly improve pregnancy outcomes or reduce obstetric complications (p

This study has certain limitations: firstly, we failed to gather certain crucial maternal demographic characteristics pertinent to thyroid dysfunction, including pregestational body mass index (BMI), smoking habits, and alcohol consumption during pregnancy. Second, additionally data on thyroid conditions during the second and third trimesters were not available, which implies that some individuals with normal thyroid function in the first trimester might have developed thyroid dysfunction later in pregnancy [13]. This lack of these data could potentially skew the results. Third, during the period of our study, TPOAb was not commonly included in thyroid function assessment for pregnant women, especially those with normal TSH levels. The absence of TPOAb data for many subjects led to our decision to exclude this marker from our analysis. This exclusion might have influenced the interpretation of findings in this study, as TPOAb positivity can significantly affect thyroid function and pregnancy outcomes [13, 18]. Finally, the study did not include an assessment of iodine nutrition, which is a critical factor in thyroid function. However, universal salt iodization is mandatory in mainland China, and according to World Health Organization (WHO) guidelines, in countries where salt iodization is prevalent and covers over 90% of the general population, including pregnant women, additional iodine supplementation is not necessary. Therefore, we did not conduct iodine nutrition assessment for all pregnant women included in the study.

In conclusion, our study revealed the incidence of thyroid disorders during pregnancy in the local area of southern China, showing a high frequency of SCH but a low frequency of overt hypothyroidism and overt hyperthyroidism. Generally, pregnant women with hypothyroidism are at a higher risk for pregnancy complications, including those with IMH, who require careful monitoring and medical intervention. However, treatment with levothyroxine did not improve pregnancy outcomes or obstetric complications. It may be more beneficial to investigate and address underlying maternal issues, such as inadequate iodine nutrition or iron deficiency, rather than simply adding levothyroxine.

ATA, American Thyroid Association; ETA, European Thyroid Association; fT4, free tetraiodothyronine; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; GTT, gestational transient thyrotoxicosis; hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; IH, isolated hypothyroxinemia; PPH, postpartum hemorrhage; PROM, premature rupture of membranes; PTU, propylthiouracil; SCH, subclinical hypothyroidism; TPOAb, thyroid peroxidase antibody; TRAb, thyroid stimulating hormone receptor antibody; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are not publicly available due hospital regulations but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

MS: data collection and manuscript writing. HZ: data collection and analysis. JLiang: data analysis. YF: study design and manuscript revision. JLou: interpretation of data for the work. BD: interpretation of data for the work. XW: supervision; substantial contributions to the conception. JC: supervision and substantial contributions to the conception or design of the work. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Written informed consent was obtained from each participant and the program was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Dongguan Maternal and Children Hospital on 1 July 2021 (reference: No. 202133). The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The authors would like to thank all colleagues for their participation in this project.

The study was funded by Basic and Applied Basic Research Program of Guangdong Province (2020A1515110308); Key Social Development Program of Dongguan City (20211800904772).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.