1 State Key Laboratory of Ultrasound in Medicine and Engineering, College of Biomedical Engineering, Chongqing Medical University, 400016 Chongqing, China

2 Department of Gynecology, Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center Liuzhou Hospital, 545006 Liuzhou, Guangxi, China

3 Department of Gynecology, Jincheng People’s Hospital, 048026 Jincheng, Shanxi, China

4 State Key Laboratory of Ultrasound in Medicine and Engineering, School of Public Health, Chongqing Medical University, 400016 Chongqing, China

Abstract

The relationship between adenomyosis and vitamin D remains largely unexplored. However, emerging evidence suggests that vitamin D deficiency may increase the risk of developing adenomyosis.

A cross-sectional study was conducted involving 190 patients diagnosed with adenomyosis and 185 healthy controls. Propensity score matching (PSM) was utilized to generate 91 matched pairs. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was employed to examine the relationship between vitamin D levels and the risk of adenomyosis. Additionally, receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was used to evaluate the diagnostic performance of vitamin D levels.

In both unmatched (44.0 nmol/L vs. 61.4 nmol/L, p < 0.001) and matched (42.3 nmol/L vs. 60.7 nmol/L, p < 0.001) groups, patients with adenomyosis exhibited significantly lower serum vitamin D levels compared to healthy controls. Multivariate logistic regression analysis demonstrated a negative association between vitamin D levels and the risk of adenomyosis in both groups. ROC analysis identified an optimal diagnostic threshold of 44.75 nmol/L for vitamin D in predicting adenomyosis.

Reduced serum vitamin D levels represent an independent risk factor for adenomyosis, with levels below 44.75 nmol/L associated with an increased risk. These findings suggest that vitamin D supplementation may serve as a potential preventive strategy against adenomyosis.

Keywords

- adenomyosis

- vitamin D

- risk factor

- diagnosis

- prevention

Adenomyosis is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within the uterine myometrium [1], with a reported prevalence of 20–35% [2]. Despite being a benign condition, adenomyosis can exhibit characteristics of malignant behavior [3]. Hysterectomy remains the definitive treatment; however, this option is particularly distressing for women seeking to preserve fertility [4]. Recognized as a manifestation of endometriosis, adenomyosis is an estrogen-dependent chronic inflammatory disease [5]. Its main symptoms include heavy menstrual bleeding, prolonged menstruation, severe dysmenorrhea, and infertility [6, 7], all of which significantly affect patient’s physical, psychological, social, and economic quality of life. The pathogenesis of adenomyosis remains incompletely understood, though it is believed to involve a combination of hormonal, genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors [8]. Given its complex etiology, investigating potential preventive factors, such as vitamin D, is of crucial importance.

Study has demonstrated that vitamin D possesses anti-proliferative, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory properties [9]. Its receptors are widely expressed in various organs, including the ovaries, endometrium, and myometrium [10], suggesting a role in women’s reproductive health. Vitamin D deficiency has been associated with an increased risk of multiple conditions, including benign gynecological disorders such as uterine fibroids and endometriosis [11, 12]. Notably, research has indicated that vitamin D can inhibit the expression of cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) in endometrial tissues [13]. Vitamin D demonstrates protective effects against endometriosis through gene regulation and immune modulation [14]. The pathogenesis of adenomyosis remains unclear, as it may involve a dysregulated feedback mechanism in the repair of uterine ligament tissues, as well as immune dysregulation, with COX-2 activation potentially playing a significant role [3, 15]. This suggests that vitamin D may mitigate the positive feedback regulation implicated in adenomyosis development. Furthermore, previous studies have reported relatively low vitamin D levels in patients with adenomyosis [16, 17]. However, a study on the serum vitamin D levels of endometriosis patients indicates that patients with endometriosis have higher reserves of vitamin D [18]. This apparent contradiction suggests that vitamin D may contribute to disease pathogenesis through multiple distinct mechanisms. Nevertheless, there is a notable lack of studies specifically examining the relationship between vitamin D levels and the risk of adenomyosis.

The multifactorial nature of adenomyosis pathogenesis poses a significant challenge to the development of specific preventive strategies. In this context, vitamin D, given its involvement in the biological processes underlying adenomyosis, has emerged as a potential preventive candidate. However, current research on the association between vitamin D and adenomyosis remains limited. To address this gap, we investigated the relationship between vitamin D levels and adenomyosis, and evaluated the potential of vitamin D as a biomarker for predicting adenomyosis risk.

Subjects: this cross-sectional study included 190 patients diagnosed with adenomyosis who attended the Department of Gynecology at Liuzhou Maternal and Child Health Hospital between January 2021 and December 2023. These individuals constituted the observation group. The control group consisted of 185 individuals who underwent routine health examinations at the same institution during the same period. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Liuzhou Maternal and Child Health Hospital.

Inclusion criteria: participants were premenopausal women with newly diagnosed adenomyosis confirmed through ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Exclusion criteria: exclusion criteria included postmenopausal women, individuals with a history of adenomyosis or prior related treatment, those with systemic inflammatory diseases or severe medical conditions, patients with pelvic/abdominal endometriosis or uterine fibroids, individuals diagnosed with gynecological malignancies, and participants who had taken vitamin D or medications related to vitamin D that may affecting calcium-phosphorus metabolism within the preceding six months.

Peripheral blood samples were collected using vacuum tubes, and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) levels were measured via chemiluminescence assay. Demographic characteristics and clinical data, including age, gravidity, parity, body mass index (BMI), and serum vitamin D levels, were recorded for both groups.

Continuous variables were presented as mean

Propensity score matching (PSM) was applied to minimize baseline characteristic differences between the two groups [21]. Stepwise logistic regression was used to select the confounders with relatively large impact on the results. Finally, the following confounding factors were included in the PSM model: age, BMI, gravidity, and parity, in order to reduce the risk of selection bias. The propensity score matching method was carried out by the statistical software package R (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria; http://www.r-project.org) and EmpowerStats (X&Y Solutions, Inc., Boston, MA, USA; https://www.empowerstats.net). According to whether subjects belonged to the adenomyosis group or not, the above factors were used as covariables to construct the propensity score (PS) by smooth curve fitting. We used the 1:1 nearest neighbor matching method without replacement and a caliper width equal to 0.05 of the logit of the propensity score standard deviation. After the completion of PSM, the p-values were used to assess the balance of covariates before and after matching, with p

Univariate and multivariate logistic regression was conducted to examine the link between vitamin D and adenomyosis. The association between vitamin D and the risk of adenomyosis was measured using odds ratio (OR). All confidence intervals (CI) were 95%. We adjusted for age, BMI, gravidity, and parity. We selected these confounders on the basis of their associations with the outcomes of interest or a change in effect estimate of more than 10%. In model 1, we did not adjust for any confounders. In model 2, we adjusted for age, and BMI. In model 3, we additionally adjusted for gravidity and parity. We considered model 3 to be the main models. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was employed to identify the optimal threshold of vitamin D levels in predicting adenomyosis.

All data analyses were performed using the statistical software package R and EmpowerStats. A two-sided p-value

This study included 190 patients with adenomyosis and 185 healthy controls. PSM was employed to adjust for potential confounding variables, including age, BMI, gravidity, and parity. Before matching, significant differences in age, gravidity, and parity were observed between the two groups, indicating an imbalance in covariate distribution. As shown in Table 1, patients with adenomyosis were generally older, had lower gravidity and lower parity compared to the healthy controls, with a greater proportion of individuals in the adenomyosis group over 40 years of age.

| Characteristic | Unmatched groups | Matched groups | |||||

| Adenomyosis group (n = 190) | Healthy group (n = 185) | p-value | Adenomyosis group (n = 91) | Healthy group (n = 91) | p-value | ||

| Age, years | 38.7 | 35.3 | 37.5 | 36.6 | 0.297a | ||

| Age, years, n (%) | |||||||

| 114 (60.0%) | 154 (83.24%) | 63 (69.23%) | 67 (73.63%) | 0.512 | |||

| 76 (40.0%) | 31 (16.76%) | 28 (30.77%) | 24 (26.37%) | ||||

| Vit D, nmol/L | 44.0 | 61.4 | 42.3 | 60.7 | |||

| Vit D, nmol/L, n (%) | |||||||

| 128 (67.37%) | 49 (26.49%) | 68 (74.73%) | 26 (28.57%) | ||||

| 62 (32.63%) | 136 (73.51%) | 23 (25.27%) | 65 (71.43%) | ||||

| BMI, kg/m2 | 23.2 | 22.4 | 0.090b | 22.4 | 22.3 | 0.747a | |

| BMI, kg/m2, n (%) | |||||||

| 63 (33.16%) | 29 (15.68%) | 20 (21.98%) | 13 (14.29%) | 0.178 | |||

| 127 (66.84%) | 156 (84.32%) | 71 (78.02%) | 78 (85.71%) | ||||

| Gravidity | 2.7 | 3.2 | 0.003b | 2.8 | 3.1 | 0.308b | |

| Gravidity, n (%) | |||||||

| 60 (31.58%) | 72 (38.92%) | 0.137 | 30 (32.97%) | 33 (36.26%) | 0.640 | ||

| 130 (68.42%) | 113 (61.08%) | 61 (67.03%) | 58 (63.74%) | ||||

| Parity | 0.9 | 1.5 | 1.19 | 1.24 | 0.616b | ||

| Parity, n (%) | |||||||

| 153 (80.53%) | 80 (43.24%) | 32 (35.16%) | 37 (40.66%) | 0.445 | |||

| 37 (19.47%) | 105 (56.76%) | 59 (64.84%) | 54 (59.34%) | ||||

Vit D, vitamin D; BMI, body mass index; a Independent samples t-test; b Mann-Whitney U test.

Through 1:1 PSM, 91 patients with adenomyosis were matched to 91 healthy controls. Post-matching, differences in these variables were significantly minimized, demonstrating effective covariate balancing and reduced bias. The mean vitamin D levels were notably lower in patients with adenomyosis compared to the healthy control group, both before matching (44.0

As shown in Table 2, vitamin D levels were significantly negative associated with adenomyosis (OR = 0.92, 95% CI: 0.90–0.94, p

| Variable | OR | 95% CI | p-value |

| Vit D | 0.92 | 0.90–0.94 | |

| Age | 1.11 | 1.07–1.16 | |

| BMI | 1.12 | 1.04–1.22 | 0.005 |

| Gravidity | 0.85 | 0.76–0.96 | 0.008 |

| Parity | 0.35 | 0.26–0.47 |

Vit D, vitamin D; BMI, body mass index; OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence intervals.

In the multifactorial logistic regression analysis, three distinct logistic regression models were utilized to further explore the relationship between vitamin D levels and the risk of adenomyosis. In the unmatched groups, OR remained stable at 0.92 across all models, however, OR showed minimal variation (0.90 to 0.91) in matched groups. All three model results suggest a significant negative correlation between vitamin D levels and the risk of adenomyosis (p

| Unmatched groups (n = 375) | Matched groups (n = 182) | |||||

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Model 1 | 0.92 | 0.90–0.94 | 0.91 | 0.88–0.94 | ||

| Model 2 | 0.92 | 0.90–0.94 | 0.91 | 0.88–0.93 | ||

| Model 3 | 0.92 | 0.89–0.94 | 0.90 | 0.87–0.93 | ||

Model 1: unadjusted. Model 2: adjust for age, BMI. Model 3: adjust for age, BMI, gravidity, parity.

Furthermore, matched analysis demonstrated that a 1-unit decrease in vitamin D levels was associated with a 10% increase in the risk of adenomyosis (OR = 0.90, 95% CI: 0.87–0.93, p

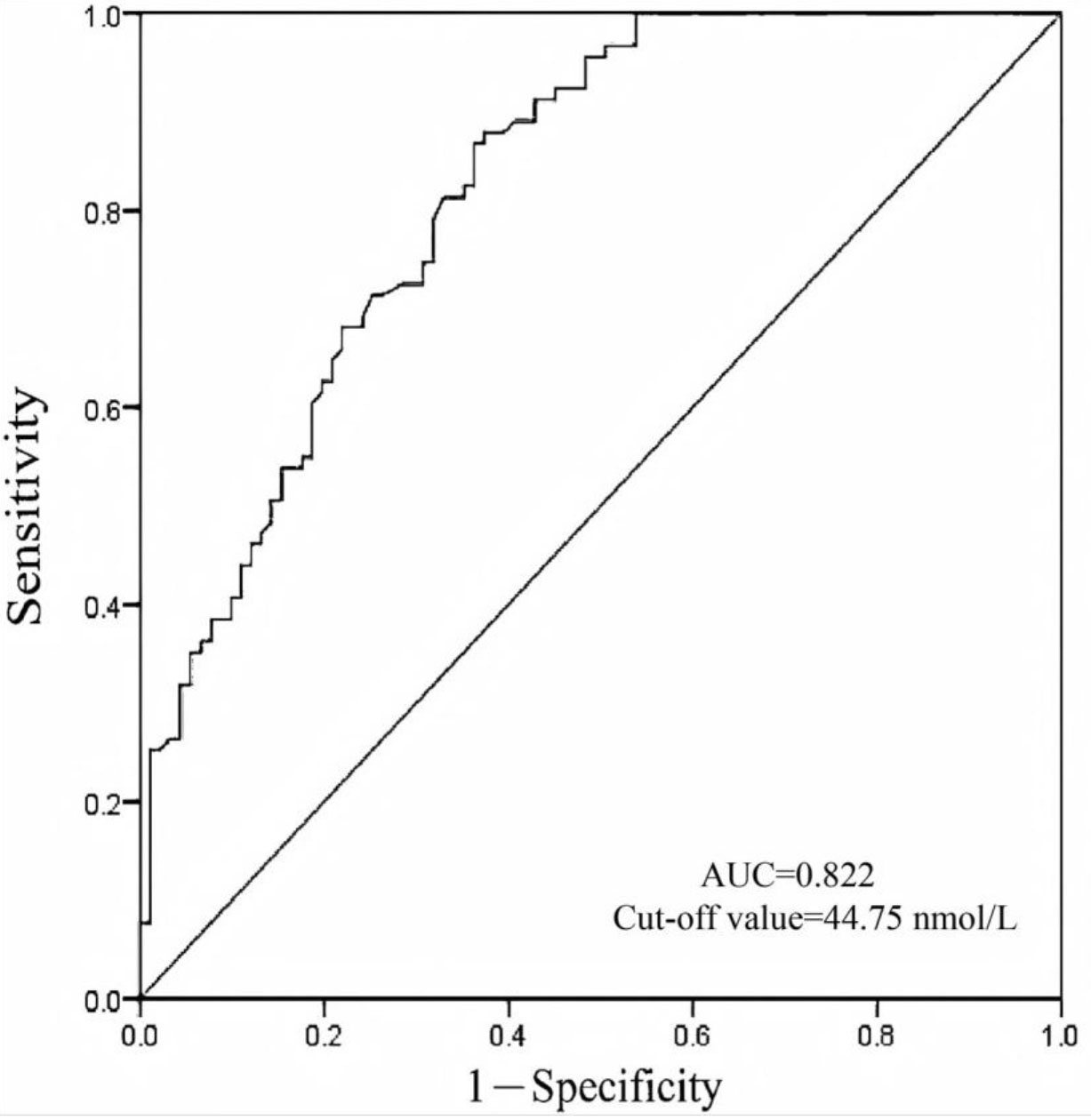

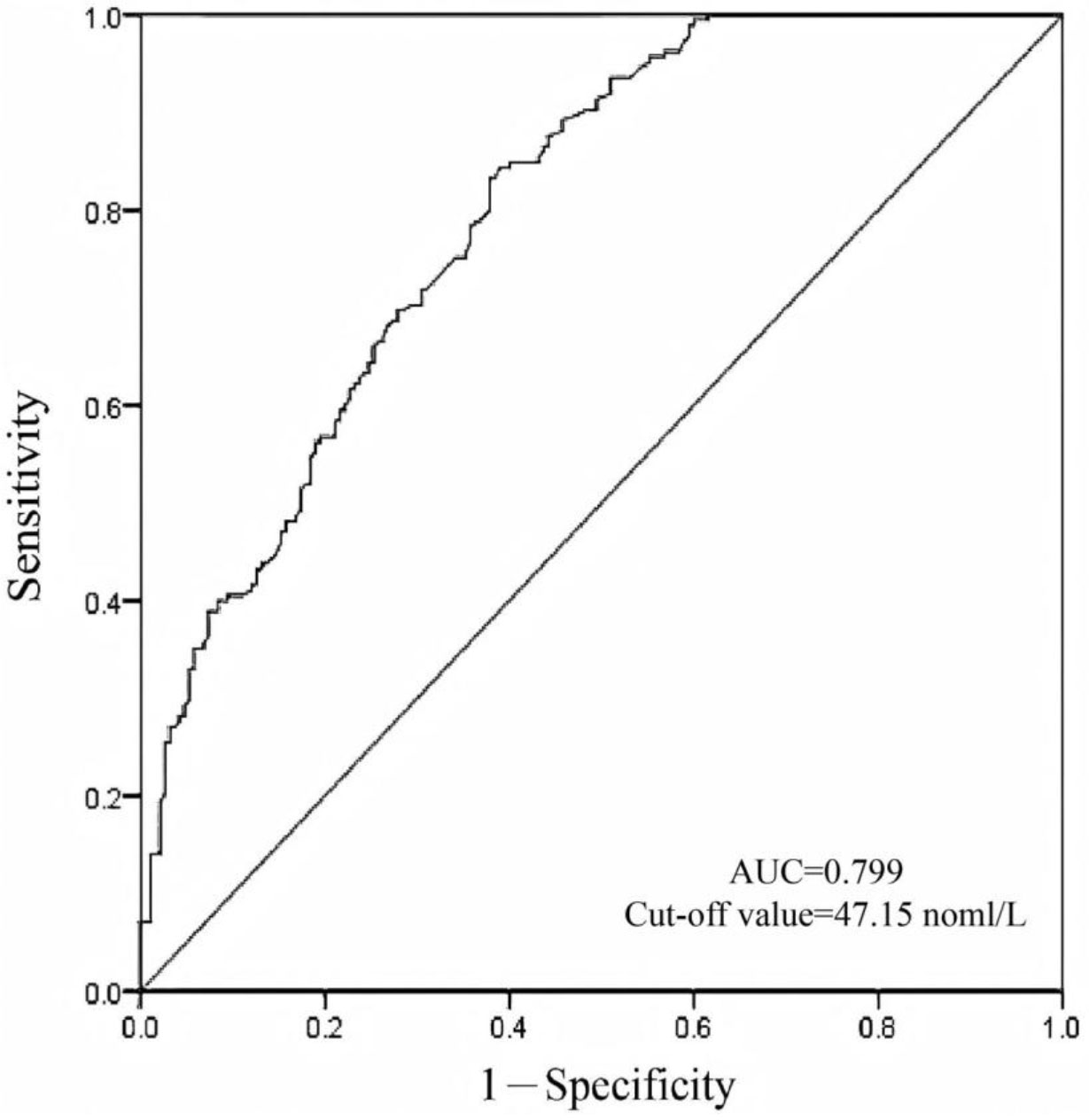

We conducted a diagnostic test evaluation and ROC curve analysis to evaluate the utility of vitamin D as a diagnostic biomarker for adenomyosis. In the matched groups, the ROC curve analysis revealed an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.822 (95% CI: 0.759–0.872), indicating good diagnostic accuracy. The optimal diagnostic threshold for vitamin D was determined to be 44.75 nmol/L (Fig. 1). At this threshold, the sensitivity was 0.637, specificity was 0.868, and overall diagnostic accuracy was 0.753. In the unmatched groups, the ROC curve analysis revealed an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.799 (95% CI: 0.755–0.843). The optimal diagnostic threshold for vitamin D was determined to be 47.15 nmol/L (Fig. 2). At this threshold, the sensitivity was 0.611, specificity was 0.843, and overall diagnostic accuracy was 0.725. These findings support the potential of vitamin D as a reliable diagnostic marker for adenomyosis.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Diagnostic value of vitamin D for adenomyosis in matched patients. The optimal cut-off value of the vitamin D is 44.75 nmol/L. AUC, area under the curve.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Diagnostic value of vitamin D for adenomyosis in unmatched patients. The optimal cut-off value of the vitamin D is 47.15 nmol/L.

In this study, we observed that patients with adenomyosis were significantly more likely to exhibit vitamin D deficiency compared to the healthy control group. Low serum vitamin D levels were identified as an independent risk factor for the development of adenomyosis, highlighting the potential utility of vitamin D supplementation in its prevention or management. Furthermore, vitamin D demonstrated promise as a diagnostic biomarker for adenomyosis, due to its strong diagnostic performance and clinical applicability. Serum vitamin D levels below 44.75 nmol/L were associated with a markedly increased risk of adenomyosis. This threshold may serve as a valuable reference for guiding further diagnostic evaluations and supporting clinical decision-making.

The pathogenesis of adenomyosis remains largely unclear, with several hypotheses proposed to explain its development. These include estrogen dominance, abnormal repair mechanisms in the uterine junctional zone, differentiation of embryonic Müllerian duct remnants, uterine stem cell theory, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition [3, 15, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26]. One widely recognized mechanism involves the abnormal injury and repair of the uterine junctional zone, which leads to the activation of COX-2 [15]. Given the complexity and uncertain etiology of adenomyosis, specific preventive strategies have yet to be clearly defined. Findings from our study suggests that low serum vitamin D levels may increase the risk of developing adenomyosis, providing a rationale for exploring vitamin D as a potential preventive measure.

Vitamin D, a group of fat-soluble steroid compounds, has receptors expressed in various organs, including the musculoskeletal, nervous, immune, and reproductive systems [27, 28]. It exerts antiproliferative, anti-inflammatory, and immunomodulatory effects [9]. Adequate vitamin D levels are associated with a reduced risk of all-cause mortality, chronic diseases, and specific autoimmune disorders [29]. According to Grant’s review, scientific evidence supports the use of vitamin D supplementation as a preventive measure against cancer [30].

Numerous studies have demonstrated that vitamin D can inhibit COX-2 production through various mechanisms. For example, Mariko Miyashita et al. [13] showed that vitamin D can suppress prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) secretion and COX-2 expression in vitro in endometriosis tissue. Michael Friedrich et al. [31] conducted in vitro experiments on breast cancer cells using vitamin D and celecoxib, and their findings revealed that vitamin D alone reduced COX-2 protein expression, while the combination of celecoxib and vitamin D reduced COX-2 protein expression by 87%. Moreover, treatment with calcitriol decreased COX-2 mRNA expression in breast cancer cells. In malignant breast cell lines and ovarian cancer tissues, a negative correlation was observed between vitamin D receptor expression and COX-2 expression [32]. This inverse association suggests a potential protective mechanism through which vitamin D may help prevent the development of adenomyosis.

In addition to the aforementioned mechanisms, the role of vitamin D in adenomyosis may also involve immune regulation and inflammation modulation. Lamia Sayegh et al. [14] proposed that vitamin D may affect the risk of endometriosis through immune modulation, such as activating CD4+ CD8+ lymphocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cells. A study demonstrated that 1,25(OH)2D3 significantly reduced interleukin 1 (IL-1) or tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-induced interleukin 8 (IL-8) mRNA expression and production in endometriotic stromal cells, suggesting that vitamin D may exert in vivo regulatory effects on inflammation in endometriosis [13]. However, some studies have reported endometriosis patients have higher levels of vitamin D, with the disparity becoming increasingly pronounced in advanced stages of the disease [18, 33]. The inconsistency in these results may be partly due to differences in study design and sample size. Unfortunately, the investigation of vitamin D’s influence on the pathogenic mechanisms underlying adenomyosis poses significant methodological challenges. Confounding may bias observational studies, and the disease itself might also theoretically lower vitamin D concentrations (reverse causality bias) [34]. Chronic pelvic pain, a common symptom of adenomyosis, may lead to reduced physical activity and outdoor exposure, potentially affecting vitamin D levels. Additionally, overlapping gynecological conditions and inflammatory processes might confound the observed associations. Environmental factors, such as sun exposure, lifestyle, obesity, and dietary intake, also influence the levels of vitamin D. However, whether vitamin D is a causative factor or a confounding factor in the disease will require future validation through large-scale, prospective studies.

Currently, the evaluation of vitamin D status is primarily guided by its role in bone health considerations. For the specific population of patients with adenomyosis, our study has established a vitamin D threshold based on available data. This threshold provides an optimal balance between sensitivity and specificity for detecting adenomyosis. Notably, our findings are the first to indicate that a vitamin D level below 44.75 nmol/L significantly increases the risk of developing adenomyosis. This threshold serves as a potential method for identifying women at higher risk of adenomyosis, enabling early detection and implementation of secondary prevention strategies, such as recommending vitamin D supplementation to mitigate disease risk. However, the clinical application of this cutoff point requires further validation through large-scale, multicenter, prospective randomized controlled trials to confirm the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in preventing adenomyosis.

While this study provides a potential foundation for understanding the role of vitamin D in the prevention of adenomyosis, several limitations should be acknowledged.

Firstly, the study cannot establish a causal relationship. Retrospective selection bias in the cases and controls may have influenced the internal validity of the findings.

Secondly, our study relied on MRI diagnosis of adenomyosis, independently reviewed by two experienced radiologists. While MRI effectively identifies typical endometriotic lesions (e.g., ovarian endometriomas), it has limitations in detecting subtle endometriosis. Additionally, this study is based on single-center data, which may be subject to selection bias, thereby potentially affecting the observed association between vitamin D and adenomyosis. Future multi-center studies that include surgical or laparoscopic verification will help to address this limitation. At the same time, the relatively small sample size of this study may limit the generalizability of the findings. Future research should prioritize large-scale, multicenter, prospective studies to confirm the relationship between vitamin D and adenomyosis and to evaluate the effectiveness of vitamin D supplementation in prevention. Such studies could also support the development of a potential screening strategies, such as measuring vitamin D concentrations during routine health check-ups to early identify high-risk populations.

Thirdly, although multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to adjust for key covariates such as age, BMI, gravidity, and parity, unmeasured confounding factors, including dietary intake, sunlight exposure, lifestyle and genetic predispositions, may still influence the results. Future studies should incorporate a broader range of potential confounding variables to more accurately assess the independent association between vitamin D and adenomyosis.

Despite these limitations, this study highlights the clinical significance of assessing vitamin D levels for the early identification of adenomyosis. Vitamin D presents a promising, safe, and cost-effective preventive strategy, particularly as a dietary supplement, and warrants further exploration in population-specific prevention strategies.

In summary, this study confirms that vitamin D deficiency is associated with an increased risk of developing adenomyosis. Regular assessment of vitamin D levels and appropriate supplementation for women with vitamin D deficiency may contribute to reducing this risk, thereby promoting improved reproductive health outcomes of women. However, further validation through large-scale, multicenter, prospective randomized controlled trials is essential to establish the efficacy of vitamin D supplementation in preventing adenomyosis.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

ZBW, DYZ, FL, HT and QLS contributed to the study’s conception and design. HJZ designed the study, wrote the manuscript text, and analyzed the data. Data collection was performed by LWei and LWang. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Liuzhou Maternal and Child Health Hospital (Ethic Approval Number: 2021-081). All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study.

Thanks for the colleagues of the Guangzhou Women and Children’s Medical Center Liuzhou Hospital and Chongqing Medical University.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used Claude 3.5 Sonnet in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.