1 Department of Women Health Care, Jiangnan University Affiliated Wuxi Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, 214002 Wuxi, Jiangsu, China

2 Department of Obstetrics, Jiangnan University Affiliated Wuxi Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, 214002 Wuxi, Jiangsu, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count syndrome (HELLP syndrome), characterized by hemolysis (H), elevated liver enzymes (EL), and a low platelet count (LP), is a severe obstetric complication. We analyzed the clinical characteristics of complete and partial HELLP syndrome.

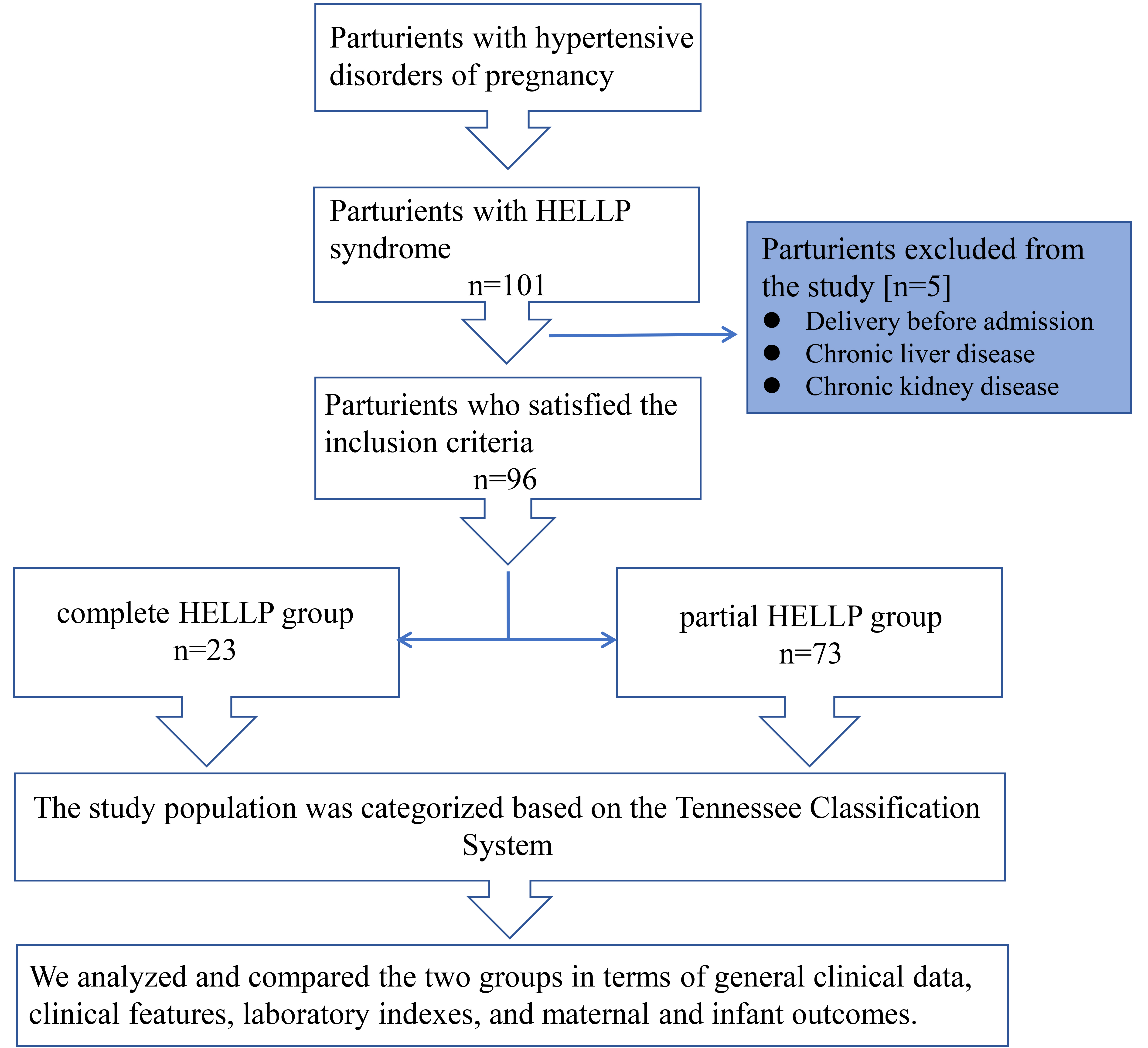

We conducted a retrospective study to collect data on 96 pregnant women with preeclampsia accompanied by HELLP syndrome. HELLP syndrome was diagnosed based on the Tennessee Classification System. General characteristics, clinical manifestations, laboratory results, complications, as well as maternal and neonatal outcomes were analyzed to compare complete and partial HELLP syndrome.

Among the 96 pregnant women with HELLP syndrome, 76% (73/96) were diagnosed with partial HELLP syndrome, while 24% (23/96) were diagnosed with complete HELLP syndrome. No statistically significant differences were found in maternal and disease characteristics between the partial and complete HELLP groups (all p > 0.05). The main symptoms of HELLP syndrome were headache and epigastric pain. Regarding diagnostic measures, the complete HELLP group had lower platelet counts (PLT) and higher total bilirubin (TBil), lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alanine transaminase (ALT), and aspartate transaminase (AST) levels compared to the partial HELLP group. For non-diagnostic measures, the complete HELLP group showed higher white blood cell counts and D-dimer levels. No statistically significant differences were observed in the remaining laboratory indexes (all p > 0.05). Similarly, there was no statistically significant differences in the incidence of maternal pregnancy complications and fetal demographic features between the two groups (all p > 0.05).

The distinction between partial and complete HELLP syndromes primarily lies in specific laboratory indexes. Both syndromes can lead to severe perinatal complications, including eclampsia, uteroplacental apoplexy, and fetal demise. Clinical diagnosis does not require strict adherence to all three criteria: H, EL, and LP. Special attention should be given to patients with partial HELLP syndrome, who require immediate treatment and intervention.

Keywords

- complete HELLP syndrome

- partial HELLP syndrome

- preeclampsia

- perinatal outcomes

- clinical features

Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count syndrome (HELLP syndrome), first named by Weinstein [1] in 1982, is a severe complication of preeclampsia characterized by hemolysis (H), elevated liver enzymes (EL), and low platelet count (LP). The incidence of HELLP syndrome is approximately 0.2%–0.8% [2]. It is a multisystemic disease with complications including liver and kidney insufficiency, thrombosis, eclampsia, and postpartum hemorrhage. In addition to these maternal complications, HELLP syndrome can result in preterm birth, fetal growth restriction, and placental abruption, significantly affecting fetal health. The maternal mortality rate is approximately 9.7%, with neonatal mortality reaching 37% [3]. Thus, HELLP syndrome poses a grave threat to the lives of both mothers and infants.

The specific diagnostic laboratory values for HELLP syndrome vary across countries and regions [4]. However, many physicians assess disease severity based on three main criteria. Complete HELLP syndrome is defined by the presence of all three criteria, whereas partial HELLP syndrome is diagnosed when one or two criteria are met [5]. Aydin et al. [6] suggested that complete and partial HELLP syndromes may represent a continuum in the natural progression of the disease. The debate continues regarding whether partial and complete HELLP syndromes constitute a continuum of the same condition or represent distinct conditions. The pathogenesis of HELLP syndrome remains unclear. Enhancing awareness of this condition is crucial for reducing maternal and infant mortality. This article reviews the clinical features of partial and complete HELLP syndromes to strengthen understanding and management of the condition and improve perinatal outcomes.

Ninety-six patients with HELLP syndrome were retrospectively enrolled from January 2016 to December 2023. HELLP syndrome was diagnosed using the Tennessee Classification System, which is globally recognized. This system includes the following laboratory findings: (1) hemolysis, defined by abnormal peripheral smear, elevated bilirubin (

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the study population selection. HELLP, hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count syndrome.

Clinical indicators collected included gestational age, body mass index (BMI) at admission, gravidity, primiparity, family history of hypertension, and history of cesarean section. Disease course and comorbidities included gestational age at delivery, systolic and diastolic blood pressure at admission, mean arterial pressure at admission, and gestational diabetes mellitus. Neonatal outcomes included assisted reproductive rate, preterm birth rate, stillbirth rate, and Apgar scores. Laboratory indicators corresponding to the most severe period of hospitalization included alanine transaminase (ALT), AST, LDH, total bilirubin (TBil), platelet count, hemoglobin, white blood cell count, and plasma fibrinogen. Maternal perinatal outcomes included eclampsia, placental abruption, and renal function impairment.

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for statistical analyses. The Shapiro-Wilk test was applied to test for normality. Differences between groups were assessed using the independent sample t-test for normally distributed continuous variables, the Mann-Whitney U test for non-normally distributed continuous variables, and the Chi-square test for categorical variables. Fisher’s exact test was applied for categorical variables with an expected frequency of less than 5. Statistical significance was set at p

Among the 96 patients with HELLP syndrome, 73 were in the partial HELLP group (76%) and 23 were in the complete HELLP group (24%). The ages of the partial HELLP group and the complete HELLP group were similar (30.3 vs. 31.8), though the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.267). Among the 96 pregnant women, there were seven twin pregnancies, but no triplet or higher-order pregnancies. Six of these pregnancies were in the partial HELLP group, and one was in the complete HELLP group, with no statistical difference between the two groups. Additionally, there were no significant differences between the two groups for maternal BMI before delivery, gravidity, primiparity, chronic hypertension, history of preeclampsia, family history of hypertension, or history of cesarean section (Table 1).

| Partial HELLP group (n = 73) | Complete HELLP group (n = 23) | Statistic values | p-values | |

| Maternal age, years | 30.3 | 31.8 | t = –1.117 | 0.267 |

| Maternal BMI before delivery, kg/m2 | 27.8 | 28.4 | t = –0.556 | 0.580 |

| Gravidity | 1 (1 | 2 (0 | Z = –0.463 | 0.643 |

| Primiparity, n (%) | 46 (63%) | 14 (61%) | 0.853 | |

| Chronic hypertension, n (%) | 11 (15%) | 3 (13%) | — | |

| History of preeclampsia, n (%) | 7 (10%) | 5 (22%) | — | 0.152 |

| Family history of hypertension, n (%) | 13 (18%) | 6 (26%) | — | 0.383 |

| History of caesarean section, n (%) | 12 (16%) | 4 (17%) | — | |

| Twin pregnancies, n (%) | 6 (8%) | 1 (4%) | — | |

| Single pregnancy, n (%) | 67 (92%) | 22 (96%) | — |

BMI, body mass index.

According to the features of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, both groups had similar gestational ages, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, and mean arterial pressure (p

| Partial HELLP group (n = 73) | Complete HELLP group (n = 23) | Statistic values | p-values | ||

| Delivery week, weeks | 33.6 | 33.0 | t = 0.575 | 0.566 | |

| Highest SBP before delivery, mmHg | 162.3 | 164.6 | t = –0.404 | 0.687 | |

| Highest DBP before delivery, mmHg | 104.9 | 104.1 | t = 0.202 | 0.841 | |

| Highest MAP before delivery, mmHg | 124.0 | 124.3 | t = –0.062 | 0.951 | |

| According to early-onset or late-onset preeclampsia | |||||

| Early-onset, n (%) | 53 (73%) | 16 (70%) | 0.778 | ||

| Late-onset, n (%) | 20 (27%) | 7 (30%) | |||

| According to antenatal or postpartum HELLP syndrome | |||||

| Antenatal, n (%) | 62 (85%) | 15 (65%) | — | 0.068 | |

| Postpartum, n (%) | 11 (15%) | 8 (35%) | |||

| Discharge time after delivery, days | 5 (4 | 5 (4 | Z = –0.707 | 0.879 | |

| Oligohydramnios | 6 (8%) | 0 | — | 0.330 | |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 20 (27%) | 6 (26%) | 0.902 | ||

| Hypothyroidism, n (%) | 7 (10%) | 0 | — | 0.191 | |

| Placenta previa, n (%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (4%) | — | 0.565 | |

SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure.

HELLP syndrome primarily presents with nonspecific clinical manifestations such as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, chest pain, and general discomfort. There was no difference in the incidence of these clinical symptoms between the two groups (Table 3). Therefore, laboratory indices play an important role in the diagnosis of HELLP. All three indicators met the inclusion criteria for the complete HELLP group; otherwise, the partial HELLP group was included. The two groups showed significant differences in ALT, AST, LDH, TBil, and platelet counts (p

| Partial HELLP group (n = 73) | Complete HELLP group (n = 23) | Statistic values | p-values | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Headache or visual symptoms, n (%) | 20 (27%) | 8 (35%) | 0.497 | |

| Upper abdominal pain, n (%) | 19 (26%) | 4 (17%) | 0.397 | |

| Chest distress, n (%) | 8 (11%) | 2 (9%) | — | |

| Nausea or vomiting, n (%) | 7 (10%) | 3 (13%) | — | 0.699 |

| Vaginal bleeding, n (%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (4%) | — | 0.565 |

| Absent and/or reversed end-diastolic flow in the umbilical artery, n (%) | 6 (8%) | 3 (13%) | — | 0.444 |

| Partial HELLP group (n = 73) | Complete HELLP group (n = 23) | Statistic values | p-values | |

| ALT, U/L | 55.0 (22.5 | 133.2 (71.0 | Z = –3.301 | 0.001 |

| AST, U/L | 51.9 (31.5 | 168.9 (97.0 | Z = –4.219 | |

| LDH, U/L | 355.0 (271.4 | 765.0 (456.0 | Z = –4.399 | |

| TBil, µmol/L | 8.4 (6.2 | 26.2 (22.5 | Z = –7.206 | |

| PLT, ×109/L | 85.0 (72.0 | 60.0 (41.0 | Z = –3.143 | 0.002 |

| Hemoglobin, g/L | 118.6 | 118.7 | t = –0.034 | 0.973 |

| White blood cell, ×109/L | 10.2 (7.7 | 13.1 (10.4 | Z = –2.356 | 0.018 |

| Fib, g/L | 3.5 (2.71 | 3.3 (2.6 | Z = –0.631 | 0.528 |

| Thrombin time, s | 17.6 (16.55 | 18.3 (16.7 | Z = –1.722 | 0.085 |

| D-dimer, mg/L | 3.5 (1.9 | 8.8 (4.6 | Z = –3.013 | 0.003 |

| Globulin, g/L | 24.1 (21.2 | 24.3 (21.8 | Z = –0.610 | 0.542 |

| Albumin, g/L | 30.2 (27.5 | 29.5 (28.2 | Z = –0.215 | 0.830 |

| Alkaline phosphatase, U/L | 134.1 (92.2 | 121.3 (100.2 | Z = –0.103 | 0.918 |

| Uric acid, µmol/L | 437.5 (382.6 | 472.0 (382.8 | Z = –1.137 | 0.255 |

| Scr, µmol/L | 68.0 (54.0 | 68.1 (52.1 | Z = –0.760 | 0.447 |

| BUN, mmol/L | 5.6 (4.3 | 5.8 (3.7 | Z = –0.077 | 0.938 |

| Ca, mmol/L | 2.1 | 2.1 | t = 0.626 | 0.533 |

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; TBil, total bilirubin; PLT, platelet; Fib, fibrinogen; Scr, serum creatinine; BUN, blood urea nitrogen.

Due to improvements in diagnostic and treatment techniques, there were no maternal deaths in either the partial or complete HELLP group. The incidences of eclampsia, placental abruption, uteroplacental apoplexy, postpartum hemorrhage, and renal function injury were higher in the complete HELLP group than in the partial HELLP group; however, these differences were not statistically significant (p

| Partial HELLP group (n = 73) | Complete HELLP group (n = 23) | Statistic values | p-values | |

| Maternal death, n (%) | 0 | 0 | — | — |

| Admission to the ICU, n (%) | 23 (32%) | 9 (39%) | 0.499 | |

| Eclampsia, n (%) | 3 (4%) | 2 (9%) | — | 0.590 |

| Pre-admission eclampsia, n (%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (4%) | — | 0.424 |

| Placental abruption, n (%) | 3 (4%) | 3 (13%) | — | 0.147 |

| Uteroplacental apoplexy, n (%) | 2 (3%) | 1 (4%) | — | 0.565 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage, n (%) | 5 (7%) | 2 (9%) | — | 0.672 |

| Acute kidney injury, n (%) | 4 (5%) | 2 (9%) | — | 0.627 |

ICU, intensive care unit.

| Partial HELLP group (n = 73) | Complete HELLP group (n = 23) | Statistic values | p-values | |

| IVF-ET, n (%) | 12 (16%) | 3 (13%) | — | |

| FGR, n (%) | 19 (26%) | 6 (26%) | 0.995 | |

| Preterm birth, 28 | 48 (66%) | 12 (52%) | 0.241 | |

| Full-term birth, 37 | 14 (19%) | 7 (30%) | 0.255 | |

| Birth weight, g | 1794.7 | 1770.9 | t = 0.129 | 0.898 |

| Perinatal death, n (%) | 9 (12%) | 4 (17%) | — | 0.504 |

| Perinatal survival, n (%) | 64 (88%) | 19 (83%) | — | 0.504 |

| 1 min Apgar | 8 (6 | 6 (2 | Z = –1.483 | 0.138 |

| 5 min Apgar | 9 (8 | 8 (7 | Z = –1.917 | 0.055 |

Note: For twins, the fetus with more serious general condition was selected for statistics, and the number of cases was recorded as 1 case. IVF-ET, in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer; FGR, fetal growth restriction.

The specific pathogenesis of HELLP syndrome remains unclear. Petca et al. [2] demonstrated that approximately 70%–80% of HELLP syndrome cases are secondary to preeclampsia. As a serious complication of preeclampsia, the main pathological changes are consistent with those seen in preeclampsia [7], such as vasospasm and reduced organ perfusion; however, the underlying mechanism of HELLP syndrome development remains unclear. The inflammatory immune system is abnormally activated in HELLP syndrome [8]. Some studies have found that patients with HELLP syndrome have a higher neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio and a lower platelet-to-lymphocyte ratio due to an increase in neutrophils in peripheral blood samples [9, 10]. One study discovered that neutrophil extracellular traps promote endothelial cell activation and further increase the risk of thrombosis through the action of interleukin-1a (IL-1a) and cathepsin G [11]. This may be related to infection status; however, the specific causes remain unknown. In this study, patients with HELLP exhibited abnormal white blood cell counts, with the complete HELLP group showing higher white blood cell counts. Inflammation has been speculated as a potential cause of HELLP syndrome. However, due to limited data, experimental results related to neutrophils, monocytes, immune cells, and complement in white blood cells were not addressed in this study and require further investigation.

HELLP syndrome is believed to result from multiple factors, pathways, and mechanisms [12]. The annual delivery count at Wuxi Maternal and Child Health Hospital is approximately 10,000, with the incidence of HELLP syndrome estimated at 0.1%. Advanced age is a key risk factor for HELLP syndrome [13]. In this study, 23 patients (23.9%) were aged over 35 years, and the average age of the 96 pregnant women was 30.7 years, higher than the optimal childbearing age recommended by the National Health Commission. Obesity (BMI

Typical symptoms of HELLP syndrome include general discomfort, right upper abdominal pain, and increased pulse pressure difference. However, these symptoms are non-specific [18]. Some pregnant women may experience nausea, vomiting, and other gastrointestinal symptoms, which are difficult to identify. Hypertension and proteinuria are not typical features of HELLP syndrome [19]. Therefore, diagnosis primarily relies on laboratory tests [18]. The examination indicators were divided into two categories: diagnostic and non-diagnostic indicators of HELLP syndrome. Based on the grouping definitions, the two groups exhibited differences in ALT, AST, LDH, TBil, and platelet counts, with the complete HELLP group presenting more severe values. However, the white blood cell count and D-dimer levels in the complete HELLP group were significantly higher than those in the partial HELLP group. This suggests that patients with preeclampsia and concurrent inflammation or hypercoagulability are more likely to develop complete HELLP syndrome. The strong reserve capacity of the kidneys makes the increase in serum creatinine (Scr) less apparent in early renal injury; when Scr levels rise, it often indicates severe kidney damage [20]. While not a prerequisite for diagnosing HELLP syndrome, this study identified 11 patients with Scr

Pregnancy termination is recommended for patients with HELLP syndrome. Severe preeclampsia and HELLP syndrome are not absolute contraindications for vaginal delivery, and the method of delivery should be based on the patient’s condition and preferences. In this study, most pregnant women underwent cesarean section for pregnancy termination, while two patients with milder conditions opted for vaginal delivery. Both newborns survived without asphyxiation. Following active treatment measures, both women were discharged within four to five days after delivery.

HELLP syndrome can result in significant adverse pregnancy outcomes and poses a threat to maternal health. Eclampsia represents the most severe stage in the progression of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy and is characterized by convulsions that occur in preeclampsia. In this study, five women with HELLP syndrome experienced convulsions, which led to fetal demise in two cases. Among these five patients, two had convulsions before admission to the hospital and were transported to the emergency room by ambulance. Three women had antenatal convulsions, while two developed postpartum eclampsia, indicating that even after delivery termination, there remains a possibility of disease exacerbation or the occurrence of eclamptic episodes. Therefore, clinicians should remain vigilant during clinical diagnosis and treatment. This phenomenon may be attributed to the increased vulnerability of the brain and kidneys to persistent vascular endothelial dysfunction after childbirth [21]. Notably, there were no maternal deaths among the HELLP syndrome cases collected in this study from 2016 to 2023, which can be attributed to the extensive experience in emergency and critical care among clinicians at our hospital and the support and cooperation of the multidisciplinary team.

Patients with HELLP syndrome are susceptible to fetal growth restriction, perinatal asphyxia, and other complications, including systemic small artery constriction, high placental vascular resistance, and placental tissue ischemia [13]. Thirteen perinatal deaths occurred during the study period. The mean maternal arterial pressure of the fetuses who died was 137 mmHg, compared to 122 mmHg for the surviving fetuses. In terms of gestational age, eight of the 13 pregnant women were between 28 and 34 weeks of gestation. During pregnancy, particularly between 28 and 34 weeks, patients with preeclampsia should closely monitor their blood pressure and receive appropriate medical treatment under supervision.

The strength of our study lies in evaluating the outcomes associated with complete and partial HELLP syndrome using data collected from a single tertiary care medical center, where consistent protocols were followed for managing HELLP syndrome. Future studies may involve collaboration with hospitals in other regions to expand the study to multiple obstetric medical centers, which would enhance the generalizability of the results.

Partial and complete HELLP syndromes differ primarily in laboratory indices, but they exhibit similarities in general characteristics, pregnancy-related complications, other laboratory tests, and neonatal demographic features. Both conditions can result in severe perinatal outcomes. Clinical diagnosis and treatment do not require the simultaneous presence of all three indicators—hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count. Partial HELLP syndrome should be considered, and timely clinical treatment and intervention are essential.

BMI, body mass index; SBP, systolic blood pressure; DBP, diastolic blood pressure; MAP, mean arterial pressure; IVF-ET, in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; TBil, total bilirubin; PLT, platelet; Scr, serum creatinine; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; Fib, fibrinogen; FGR, fetal growth restriction.

Data is provided within the manuscript. All data in this paper are from the medical database of Wuxi Maternal and Child Health Hospital. To protect patient privacy, the specific data involved in this study is not publicly available. All data are available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

HG designed the research study and analyzed the data. JYC collected the data. HQW designed the research study. MHJ and YG provided help and advice on the data collection and ethics application. YLF designed the work, reviewed the article, and provided financial support. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was reviewed and approved by the Ethics committee of the Wuxi Maternal and Child Health Hospital (No. 2024-06-0507-14). This is a retrospective research paper, and the article does not show any clinical details or images that may infer the identity of patients. All participants provided informed consent.

Not applicable.

This study was supported by the following funding sources: Jiangsu Maternal and Child Health Research Project (F202135); Project of Women’s Health Care Department under the Key Disciplines of Maternal and Child Health Care in Jiangsu Province (SFY3-FB2021).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

In preparation for this work, we used ChatGpt-3.5 to check spelling and grammar. After using this tool, we review and edit the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.