1 Department of Pediatrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University, 325000 Wenzhou, Zhejiang, China

2 Department of Anaesthesia, Women’s Hospital, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, 310002 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

3 Department of Pediatrics, Yiwu Maternity and Children Hospital, 322000 Yiwu, Zhejiang, China

4 Department of Pediatrics, The Quzhou Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (Quzhou People’s Hospital), 324000 Quzhou, Zhejiang, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) is a major contributor to mortality in extremely preterm infants. Therefore, it is essential to identify effective clinical prognostic indicators of BPD and implement early interventions. The objective of this study was to evaluate the predictive value of erythrocyte-related indices, such as hemoglobin (Hb) and hematocrit (Hct), for BPD.

This retrospective cohort study included 413 neonates with a gestational age (GA) of < 32 weeks who were admitted to The First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University between January 2019 and January 2024. Maternal and infant characteristics were recorded, and Hb and Hct levels were measured on days 1, 3, 14 and 28 of life (DOL1, DOL3, DOL14, and DOL28, respectively).

Compared to non-BPD patients (n = 170), BPD patients (n = 218) had a lower GA (p < 0.001), birth weight (p < 0.001), 1-minute postnatal Apgar scores (p < 0.001) and 5-minute postnatal Apgar scores (p < 0.001). However, they exhibited higher rates of intubation in the delivery room (p < 0.001), surfactant treatment (p < 0.001), diuretic treatment (p < 0.001), caffeine treatment (p < 0.001), postnatal steroid use (p < 0.001), hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus (hsPDA) (p < 0.001), intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) (p = 0.001), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) (p < 0.001), duration of invasive mechanical ventilation (IMV) ≥1 week (p < 0.001), and number of packed red blood cell (PRBC) transfusions (p < 0.001). In addition, BPD patients received PRBC transfusions earlier (p = 0.004), had lower Hb levels on DOL1 (p = 0.001), DOL3 (p < 0.001) and DOL14 (p < 0.001), but higher levels on DOL28 (p = 0.003). They also had lower Hct levels on DOL1 (p = 0.004), DOL3 (p < 0.001) and DOL14 (p < 0.001), but higher levels on DOL28 (p = 0.001). An Hb level of ≤150 g/L on DOL3 (DOL3-Hb) was an early predictor for BPD (adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 3.222, p = 0.002), with high sensitivity (69.72%) and specificity (78.24%). The number of PRBC transfusions was also a significant risk factor for BPD (adjusted OR = 4.436, p < 0.001).

Significant predictors of BPD included DOL3-Hb 150 g/L and the number of PRBC transfusions, with DOL3-Hb serving as an early predictor.

Keywords

- erythrocyte-related indices

- hemoglobin

- hematocrit

- bronchopulmonary dysplasia

- predictor

Bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) was initially described by Northway et al. [1] as a chronic lung disease in premature infants, requiring mechanical ventilation and oxygen therapy for neonatal respiratory distress syndrome (NRDS). In recent years, the survival rate for extremely premature infants has significantly increased due to advances in obstetrical and neonatal care, such as antenatal steroid treatment [2], surfactant therapy [3], oxygen saturation target, caffeine, and mechanical ventilation strategies [4]. Meanwhile, promising therapies are being transferred from bench to bedside, including mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs), insulin-like growth factor 1/binding protein-3 (IGF-1/IGFBP-3), and interleukin 1 receptor (IL-1R) antagonist (anakinra) [5]. Nevertheless, there has not been a decrease in the incidence of BPD [6], with an estimated prevalence ranging from 10.8% to 37.1% among preterm neonates born at 24 to 31+6 weeks gestational age (GA) and a birth weight (BW) of

BPD is characterized by a large and simplified alveolar structure, and a reduced and dysmorphic vascular bed [8]. The pathogenesis of BPD is multifactorial and includes immature lungs, NRDS, barotrauma, volutrauma, oxygen toxicity, sepsis, inflammation and gene specificity. BPD is associated with long-term pulmonary morbidities, such as reduced lung function, increased risk of emphysema, high incidence of wheezing, impaired growth and mental development, as well as cerebral palsy [9, 10]. Despite extensive research, the ability to predict which infants will develop BPD early in life remains challenging. A regression model that improves the accuracy of predicting BPD in preterm infants was recently proposed [11]. This model includes mechanical ventilation lasting

Anemia is common among preterm infants and can result in tissue hypoxia, anaerobic metabolism and the accumulation of lactic acid, as well as giving rise to inflammation [13]. Hemoglobin (Hb) and hematocrit (Hct) levels are significant erythrocyte-related indices that can be derived from routine hematologic parameters. Decreased levels of these markers are characteristic of anemia. Previous studies have reported that lower Hb or Hct levels were closely related to BPD. Duan et al. [14] reported that preterm infants with BPD had lower Hct level than those without BPD on days 1, 7, 14 and 21 after birth, and that early anemia within 14 days after birth was a risk factor for BPD. These researchers also found that Hb

Hence, the objective of this study was to evaluate the predictive value for BPD of erythrocyte-related indices, such as Hb and Hct, in preterm infants on days 1, 3, 14 and 28 of life (DOL1, DOL3, DOL14 and DOL28, respectively).

This retrospective cohort study included 413 neonates with GA

Detailed data was collected on all mothers and infants. Maternal information included age, mode of delivery, complications, administration of prenatal steroids (four doses of 6 mg of dexamethasone given intramuscularly at 12-h intervals), prenatal magnesium sulfate, premature rupture of membranes, and chorioamnionitis. Infant data included GA, BW, sex, Apgar scores (measured at 1 and 5 minutes postnatal), intubation in the delivery room, small for gestational age (SGA) status, surfactant treatment [poractant alpha-Curosurf® (1122246, Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A, Parma, Italy), with an initial dose of 200 mg/kg, followed by 100 mg/kg for subsequent doses] [16], caffeine treatment [caffeine citrate injection (21827, Chiesi Farmaceutici S.p.A, Parma, Italy), a 20 mg/kg intravenous loading dose, followed by a maintenance dose of 5 to 10 mg/kg, once per day], diuretics treatment [hydrochlorothiazide tablets (22043011, Changzhou Pharmaceutical Factory, Changzhou, Jiangsu, China), 1 to 2 mg/kg, twice per day. Spironolactone tablets (T22N069, Hangzhou Minsheng Pharmaceutical Co.,Ltd., Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China), 1 to 2 mg/kg, twice per day], postnatal steroid use [dexamethasone sodium phosphate injection (52106112, TianJin KingYork Group Hubei TianYao Pharmaceutical Co.,Ltd., Xiangyang, Hubei, China), cumulative dose of 0.89 mg/kg over 10 days] [17], nosocomial sepsis (indicated by positive blood cultures and systemic symptoms), nosocomial pneumonia, hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus (hsPDA), intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH), retinopathy of prematurity (ROP), timing of the first packed red blood cell (PRBC) transfusion, total number of PRBC transfusions, duration of invasive mechanical ventilation, and length of hospital stay. BPD was diagnosed when supplemental oxygen was required for more than 28 days, with severity assessed according to the oxygen concentration needed at 36 weeks PMA or at discharge (whichever came first): mild BPD (breathing ambient air), moderate BPD (

Anemia in the neonatal period (

Peripheral venous blood samples were collected from the radial vein of patients on DOL1 (within 2 h of birth), DOL3, DOL14 and DOL28, in accordance with the diagnostic and treatment protocols in our center. Blood samples were collected on DOL1 for routine assessment, on DOL3 to confirm and evaluate the infection, and on DOL14 and DOL28 to assess anemia, thyroid function, vitamin D levels, liver and kidney function, and other indicators. Additionally, Hb and Hct values were obtained from the mother in the 24 h period prior to delivery. A complete blood count was conducted using an XN-350 instrument (SYSMEX, Japan).

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 23.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Continuous variables were reported as the mean

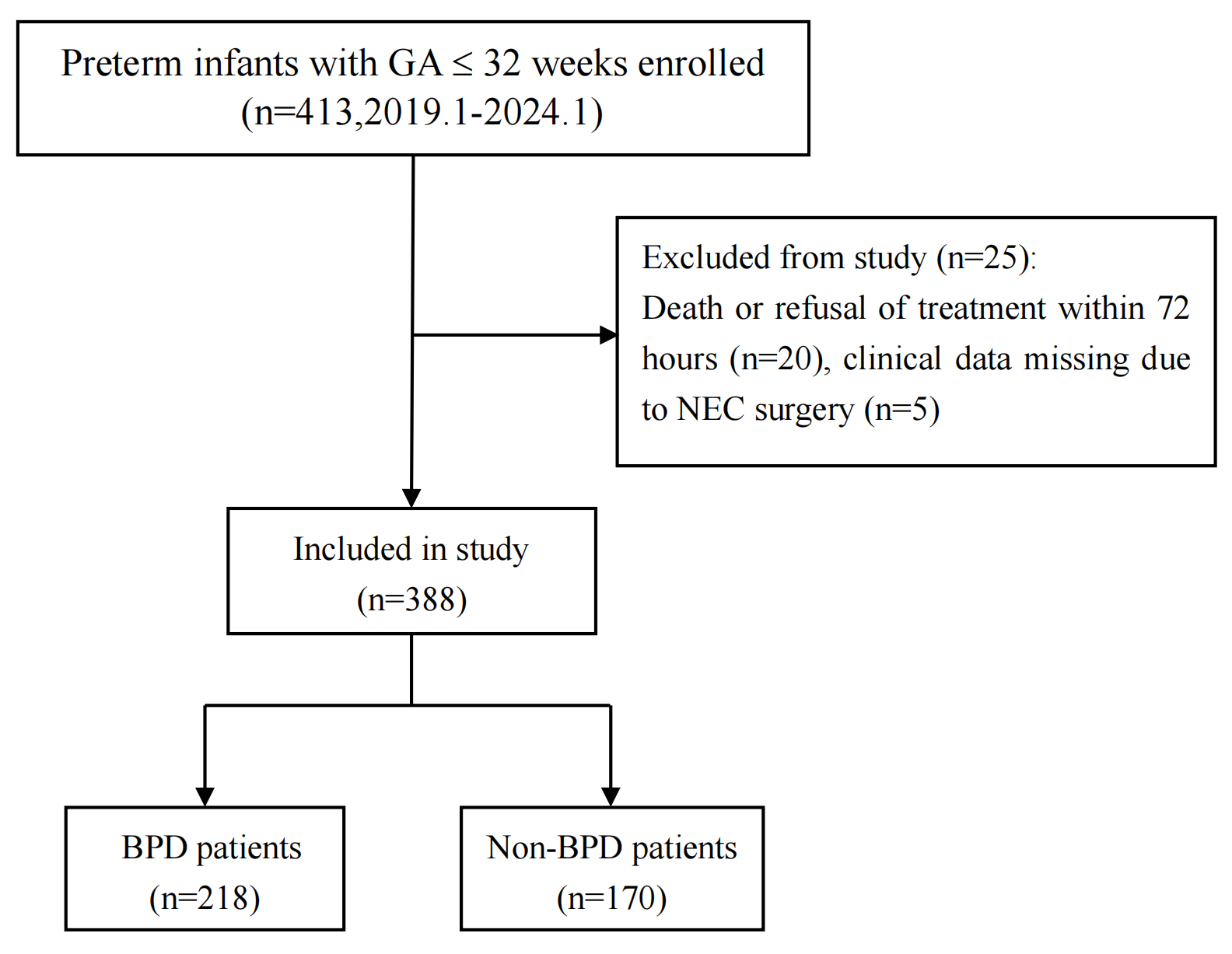

A total of 413 preterm infants with a GA

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Flow chart for this study. Abbreviations: GA, gestational age; NEC, necrotizing enterocolitis; BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia.

| BPD patients | Non-BPD patients | p-value | ||

| (n = 218) | (n = 170) | |||

| Maternal age, years, median (P25, P75) | 30 (27, 34) | 30.5 (27, 34) | –1.340 | 0.180 |

| Maternal pregnancy-induced hypertension, n (%) | 52 (23.9%) | 41 (24.1%) | 0.004 | 0.952 |

| Maternal diabetes, n (%) | 51 (23.4%) | 49 (28.8%) | 1.472 | 0.225 |

| Premature rupture of membranes, n (%) | 73 (33.5%) | 69 (40.6%) | 2.076 | 0.150 |

| Vaginal delivery, n (%) | 100 (45.9%) | 63 (37.1%) | 3.045 | 0.081 |

| Chorioamnionitis, n (%) | 42 (19.3%) | 26 (15.3%) | 1.043 | 0.307 |

| Prenatal steroids, n (%) | 114 (52.3%) | 99 (58.2%) | 1.362 | 0.243 |

| Prenatal magnesium sulfate, n (%) | 76 (34.9%) | 75 (44.1%) | 3.442 | 0.064 |

| Gestational age, weeks, median (P25, P75) | 28.9 (27.7, 29.9) | 31.0 (30.3, 31.6) | –12.689 | |

| Birth weight, g, mean | 1187 | 1500 | 11.444 | |

| Male, n (%) | 130 (59.6%) | 90 (52.9%) | 1.742 | 0.187 |

| Small for gestational age, n (%) | 29 (13.3%) | 20 (11.8%) | 0.205 | 0.651 |

| Intubation in the delivery room, n (%) | 100 (45.9%) | 21 (12.4%) | 50.005 | |

| Apgar score at 1 min postnatal, median (P25, P75) | 6 (5, 8) | 8 (6, 9) | –4.719 | |

| Apgar score at 5 min postnatal, median (P25, P75) | 9 (8, 9) | 9 (9, 10) | –5.727 | |

| Surfactant treatment, n (%) | 182 (83.5%) | 85 (50.0%) | 49.908 | |

| Diuretics treatment, n (%) | 122 (56.0%) | 4 (2.4%) | 125.188 | |

| Caffeine treatment, n (%) | 187 (85.8%) | 73 (42.9%) | 81.323 | |

| Postnatal steroids, n (%) | 49 (22.5%) | 0 (0%) | 43.734 | |

| Invasive mechanical ventilation | 42 (19.3%) | 2 (1.2%) | 31.087 | |

| Nosocomial pneumonia, n (%) | 72 (33.0%) | 52 (30.6%) | 0.261 | 0.609 |

| Nosocomial sepsis, n (%) | 31 (14.2%) | 15 (8.8%) | 2.663 | 0.103 |

| hsPDA, n (%) | 104 (47.7%) | 35 (20.6%) | 30.552 | |

| Intraventricular hemorrhage, n (%) | 20 (9.2%) | 2 (1.2%) | 11.423 | 0.001 |

| Retinopathy of prematurity, n (%) | 24 (11.0%) | 2 (1.2%) | 14.771 | |

| Number of PRBC transfusions, median (P25, P75) | 2 (1, 4) | 1 (0, 1) | –13.510 | |

| Day of first PRBC transfusion, median (P25, P75) | 14 (6, 27) | 33 (26, 41) | –2.880 | 0.004 |

| Length of hospital stay, days, mean | 72.8 | 43.2 | –18.870 |

SD, standard deviation; hsPDA, hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus; PRBC, packed red blood cell.

Patients with BPD exhibited significantly lower levels of Hb on DOL1 (p = 0.001), DOL3 (p

| Parameters | BPD patients | Non-BPD patients | t | p-value | |

| (n = 218) | (n = 170) | ||||

| Hb, g/L | |||||

| DOL1 | 163.47 | 170.74 | 3.272 | 0.001 | |

| DOL3 | 145.20 | 160.16 | 6.425 | ||

| DOL14 | 121.14 | 131.13 | 5.199 | ||

| DOL28 | 112.5 | 107.3 | –3.037 | 0.003 | |

| Maternal | 110.2 | 112.2 | 1.440 | 0.151 | |

| Hct, % | |||||

| DOL1 | 49.0 | 50.7 | 2.862 | 0.004 | |

| DOL3 | 43.2 | 47.1 | 5.788 | ||

| DOL14 | 35.9 | 38.7 | 4.999 | ||

| DOL28 | 33.5 | 31.8 | –3.441 | 0.001 | |

| Maternal | 33.4 | 32.8 | 1.634 | 0.103 | |

Hb, hemoglobin; Hct, hematocrit; DOL, day of life.

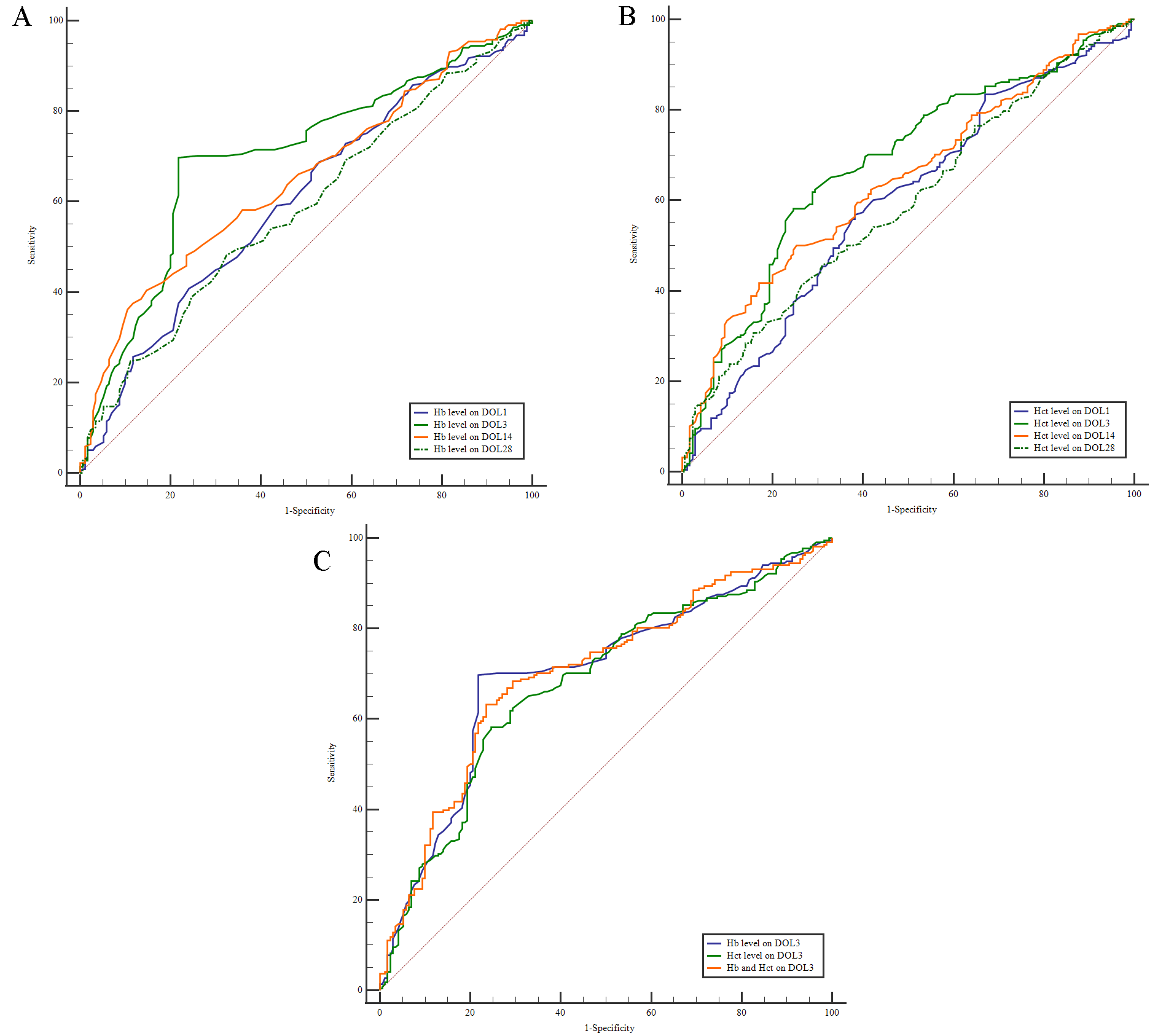

ROC analysis was performed to assess the predictive value of Hb and Hct levels for the diagnosis of BPD. Cut-off values for Hb and Hct levels were calculated for DOL1, DOL3, DOL14, and DOL28. An Hb level on DOL3 (DOL3-Hb) of

| Parameters | Cut-off value | Sensitivity | Specificity | PPV | NPV | Accuracy | AUC (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Hb, g/L | |||||||||

| DOL1 | 158 | 40.83 | 76.88 | 68.99 | 50.19 | 56.44 | 0.603 (0.552–0.652) | 0.0004 | |

| DOL3 | 150 | 69.72 | 78.24 | 80.42 | 66.83 | 73.45 | 0.700 (0.652–0.745) | ||

| DOL14 | 111 | 37.61 | 88.24 | 80.39 | 52.45 | 59.79 | 0.650 (0.600–0.697) | ||

| DOL28 | 112 | 48.17 | 67.65 | 65.63 | 50.44 | 56.70 | 0.585 (0.534–0.634) | 0.0034 | |

| Hct, % | |||||||||

| DOL1 | 49.6 | 56.88 | 61.76 | 65.61 | 52.76 | 59.02 | 0.593 (0.542–0.642) | 0.0014 | |

| DOL3 | 44.1 | 58.26 | 75.29 | 75.15 | 58.45 | 65.72 | 0.679 (0.631–0.726) | ||

| DOL14 | 35.0 | 50.00 | 74.71 | 71.71 | 53.81 | 60.82 | 0.643 (0.593–0.691) | ||

| DOL28 | 35.7 | 30.73 | 84.12 | 71.28 | 48.64 | 54.12 | 0.593 (0.542–0.642) | 0.0012 | |

| Hb and Hct on DOL3 | 150 and 44.1 | 63.30 | 76.47 | 77.53 | 63.33 | 69.07 | 0.702 (0.653–0.747) | ||

PPV, positive predictive value; NPV, negative predictive value; AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Analysis of ROC curves. (A) ROC curve analysis was conducted to determine the cut-off value for the Hb level on DOL1, DOL3, DOL14, and DOL28 in relation to BPD. (B) ROC curve analysis was performed to determine the cut-off value for the Hct level on DOL1, DOL3, DOL14, and DOL28 in relation to BPD. (C) ROC curve analysis was conducted to determine the cut-off value for Hb and Hct levels on DOL3 in relation to BPD. ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

The factors associated with BPD in premature infants included GA, BW, Apgar scores at 1 and 5 minutes postnatal, intubation in the delivery room, surfactant treatment, caffeine treatment, duration of invasive mechanical ventilation

| SE | Wald | p-value | Adjusted OR | 95% CI | ||

| Gestational age | –1.039 | 0.198 | 27.553 | 0.354 | 0.240–0.521 | |

| Birth weight | 0.002 | 0.001 | 3.503 | 0.061 | 1.002 | 1.000–1.003 |

| Apgar score at 1 min postnatal | 0.108 | 0.109 | 0.971 | 0.324 | 1.114 | 0.899–1.380 |

| Apgar score at 5 min postnatal | –0.253 | 0.192 | 1.729 | 0.189 | 0.777 | 0.533–1.132 |

| Intubation in the delivery room | 0.653 | 0.545 | 1.439 | 0.230 | 1.922 | 0.661–5.590 |

| Caffeine treatment | 0.693 | 0.384 | 3.259 | 0.071 | 2.000 | 0.942–4.244 |

| Duration of IMV | –1.202 | 1.070 | 1.262 | 0.261 | 0.301 | 0.037–2.448 |

| Surfactant treatment | 0.459 | 0.367 | 1.567 | 0.211 | 1.582 | 0.771–3.245 |

| hsPDA | 0.380 | 0.378 | 1.012 | 0.315 | 1.462 | 0.697–3.066 |

| Number of PRBC transfusions | 1.490 | 0.270 | 30.343 | 4.436 | 2.611–7.538 | |

| (DOL3-Hb) | 1.170 | 0.383 | 9.350 | 0.002 | 3.222 | 1.522–6.822 |

IMV, invasive mechanical ventilation; hsPDA, hemodynamically significant patent ductus arteriosus; PRBC, packed red blood cell; DOL3-Hb, the Hb level on the third day of life; SE, standard error; OR, odds ratio.

Although BPD is the most common clinical issue of prematurity, accurately predicting this condition at an early stage remains challenging. Clinical prediction models, echocardiogram measurements, lung function tests, epigenetic factors and various biomarkers have all been suggested as potential early indicators of BPD [23, 24, 25], but have yet to be consistently validated. Anemia of prematurity (AOP) is frequently observed in preterm infants, especially in those born at a GA

Maternal anemia during pregnancy is a known risk factor for anemia in extremely low birth weight (ELBW) infants (BW

AOP is influenced by various factors, such as rapid postnatal growth, blood loss due to medical procedures, and deficiencies in essential micronutrients necessary for red blood cell production [35]. Several clinical practices have been implemented to reduce the severity of AOP. One such practice, delayed cord clamping (DCC), allows blood to transfer from the placenta to the newborn, thereby increasing Hb level and decreasing the need for PRBC transfusions [36]. However, a large randomized trial found that DCC (lasting at least 60 s) did not impact the incidence of BPD in infants born at GA

Typically, the Hb level falls significantly during the first week after birth, leading to AOP [40]. PRBC transfusions are a key intervention for addressing AOP, with up to 40% of very low birth weight (VLBW) infants [41] and 90% of ELBW infants receiving PRBC transfusions during their hospital stay [42]. The Effects of Transfusion Thresholds on Neurocognitive Outcomes of Extremely Low-Birth-Weight Infants (ETTNO) trial and Transfusion of Prematures (TOP) trial have shown that receiving relatively low levels of Hb before transfusion, did not have any negative effect on the incidence of BPD [43, 44]. However, numerous studies have reported that PRBC transfusions were an independent risk factor for BPD in preterm infants. Lee et al. [45] found that frequent PRBC transfusions in the first week of life and a higher total volume of PRBC transfusions were associated with an increased risk of BPD. We also found that PRBC transfusions were more frequent in patients with BPD compared to those without, suggesting it was a significant risk factor. Following PRBC transfusion, erythrocytes release heme, which is subsequently broken down and raises the serum iron level. Free radicals generated by the excess iron can lead to tissue damage. Since premature infants are particularly susceptible to oxidative damage [46], this oxidative stress and the resulting inflammatory cascade may provide an explanation for the development of BPD [47].

Recombinant human erythropoietin (rhEPO) has the ability to promote erythropoiesis and reduce the need for PRBC transfusions in AOP cases [48]. Bui et al. [49] reported that administration of rhEPO (250–300 U/kg) three times a week via intravenous or subcutaneous injection reduced the occurrence of BPD. Research on animals has demonstrated that erythropoietin (EPO) can stimulate angiogenesis [50], enhance alveolar development, reduce lung fibrosis during oxygen exposure, and inhibit transforming growth factor-

The present work has several limitations. First, this was a retrospective study based on data from a single center, and lacks external validation. Larger prospective studies are required to better understand the role and clinical significance of Hb level in the onset and progression of BPD. Secondly, there may be a selection bias since we excluded some patients who either died or were not treated before being diagnosed with BPD. These preterm infants might also be at a higher risk for BPD due to intubation. Thirdly, Villar et al. [52] proposed that preterm birth can no longer be defined by GA alone since this approach fails to provide any pathophysiologic insights or assessment of specific risks. Premature infants are defined by GA ˂37 weeks in our research without considering their phenotypes. In the future study, we will incorporate new theories to define preterm birth and assess the outcomes of different phenotypes on BPD. Despite these limitations, our study is highly relevant to clinical practice and provides new insights that could assist in the management and prediction of outcomes for preterm infants.

In summary, this study demonstrated that patients with BPD had lower Hb and Hct levels up to DOL14. DOL3-Hb

BPD, bronchopulmonary dysplasia; MSCs, mesenchymal stromal cells; IL-1R, interleukin 1 receptor; IGF-1/IGFBP-3, insulin-like growth factor 1/binding protein-3; Hb, hemoglobin; Hct, hematocrit; DOL, day of life; GA, gestational age; BW, birth weight; MED1, mediator complex subunit 1; PGC-1

All data reported in this paper will also be shared by the corresponding author upon request.

YS and RZ designed the study. CC and SW analyzed the data and performed the statistical analysis. RZ and YL collected data. CL designed of the work. QW interpreted of data of the work. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Wenzhou Medical University (No.KY2021-R083) and followed the Helsinki Declaration. Written informed consent was obtained from parents when patients were admitted to hospital.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

All phases of this study were supported by Wenzhou Science and Technology Bureau, China (Y20210274); Zhejiang Medical Association clinical research fund project, China (2024ZYC-B51).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.