1 Department of Gynecology, First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, 400016 Chongqing, China

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Dianjiang County Hospital of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 408399, Chongqing, China

Abstract

With the increase in cesarean sections, the occurrence of cesarean scar pregnancies has shown a significant upward trend. To investigate the high-risk factors for hemorrhage during hysteroscopy for cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP).

This is a retrospective case-control study. A total of 338 cases of CSP were divided into-hemorrhage group and non-hemorrhaged group according to the volume of hemorrhage. The collected data included maternal age, duration of amenorrhea, frequency and interval time of cesarean sections, number of induced abortions, pre-treatment human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) levels, gestational sac length, myometrial thickness at the uterine scar, blood flow signal around the gestational sac as detected by ultrasound, and CSP classification. Statistical analysis was performed to assess differences between the two groups.

Statistically significant differences between the two groups were observed in the duration of amenorrhea, gestational sac length, myometrial thickness at the uterine scar, and blood flow signal around the gestational sac. Hysteroscopic curettage for CSP was found to be safe and feasible when the duration of amenorrhea was <49 days, the gestational sac length was <30 mm, the resistance index (RI) of the blood flow signal around the gestational sac was >0.4, and the myometrial thickness at the uterine scar was >2 mm.

Hysteroscopic curettage is a safe and effective procedure for CSP in carefully selected patients.

Keywords

- cesarean scar pregnancy

- hysteroscopy

- hemorrhage

- risk factors

Cesarean scar pregnancy (CSP) refers to a rare type of ectopic pregnancy in which the fertilized egg is implanted in the scar from a previous cesarean section. The incidence of CSP is estimated to be between 1 in 2216 and 1 in 1800, representing 1.15% of women with a history of cesarean section [1]. At present, there are at least 31 reported treatments for CSP [2], including surgical, medical, minimally invasive approaches [uterine artery embolization (UAE), high intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU), balloon], expectant management, and multiple combinations thereof. No particular treatment is considered optimal [3, 4]. Hysteroscopic curettage of pregnancy tissue is an effective treatment, but is limited by the risk of uncontrollable hemorrhage during the operation. However, it can still be considered safe and effective in certain cases. In the present study, we retrospectively analyzed 338 patients with CSP who underwent hysteroscopic curettage. Our aim was to identify risk factors for hemorrhage, thus providing a clinical basis for the early diagnosis and treatment of CSP.

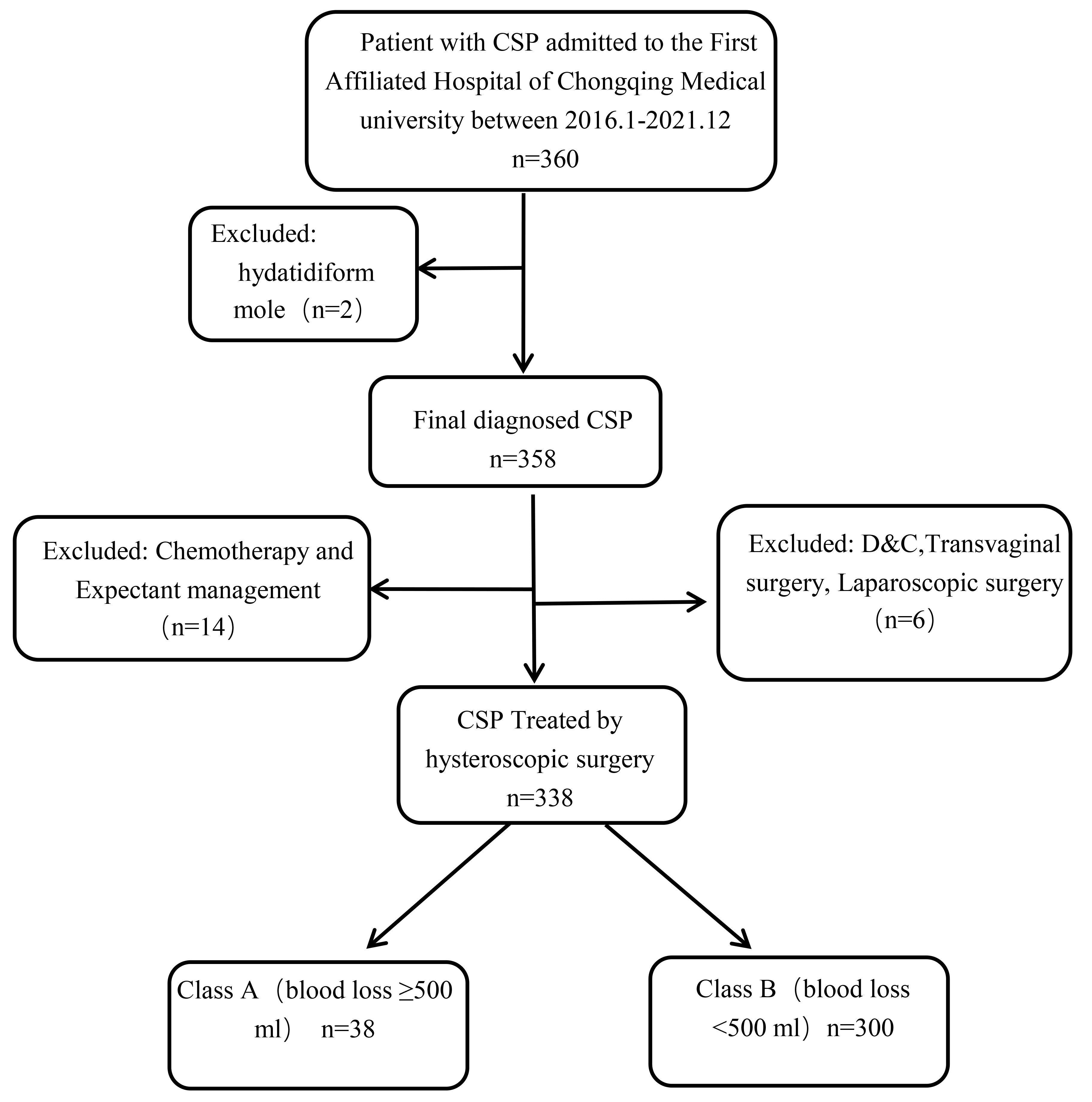

This is a retrospective case-control study. A total of 360 cases of CSP were identified in the Department of Gynecology, First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, between January 2016 and December 2021. All patients underwent hysteroscopic curettage as treatment.

The inclusion criteria were: complete clinical and follow-up data; elevated human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) level; history of cesarean section; ultrasound demonstrating an empty uterine cavity and cervical canal; gestational sac implanted in the lower segment of the anterior wall of the uterus; stable vital signs; patients were fully informed of the various treatment methods and had voluntarily chosen hysteroscopic surgery. There were no contraindications for the operation based on preoperative physical examination and ancillary examinations (complete blood count, coagulation tests, liver and kidney function, electrolytes, blood glucose, electrocardiogram). The exclusion criteria were: evidence of a systemic infection or severe local infection; heart, lung, liver, or kidney complications; coagulation dysfunction; presence of trophoblastic disease; presence of malignant tumor; the patient chose a treatment method other than hysteroscopy.

Two cases with hydatidiform mole were excluded from the final analysis. Fourteen cases were treated with medications with expected outcomes, while 6 cases were excluded from uterine curettage, vaginal surgery, and laparoscopic surgery. The final cohort for analysis therefore consisted of 338 cases.

All patients provided informed consent prior to the operation. The information given to patients explained the risks associated with massive bleeding, including the possibility of requiring emergency surgery or potentially a hysterectomy. The cervix was dilated using oral or vaginal misoprostol 1 hour prior to surgery. Preparations were made for blood transfusion, fluid replacement, and emergency surgery. Antibiotics were given perioperatively to prevent infections.

The surgical instrument used was an intraluminal hysteroscope (StrykerHD1288, Kalamazoo, MI, USA), and the perfusion fluid consisted of 5% glucose. Local anesthesia with lidocaine block was used. All procedures were performed by the same team of doctors. After routine disinfection, hysteroscopy was performed to determine the position, shape, and size of the pregnancy, followed by curettage. A follow-up hysteroscopy was performed to determine if there was residual bleeding. If an active hemorrhage was detected during the operation, a water bag cervical tube was used to compress the bleeding site.

According to the literature, the standard criterion for postpartum hemorrhage is when the amount of bleeding during and within 24 h after the operation reached 500 mL. Patients with

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Flow chart used for selection of the study population. CSP, cesarean scar pregnancy; D&C, dilatation and curettage.

The following data was collected for each patient: age, days of amenorrhea, frequency and interval time of cesarean section, number of induced abortions, hCG level before treatment, gestational sac length, CSP classification, blood flow signal around the gestational sac, and amount of hemorrhage.

The Expert Consensus on the Diagnosis and Treatment of Scar Pregnancy after Cesarean Section issued by the Chinese Medical Association in 2016 defines several types of CSP. Type I refers to the part of the gestational sac located at the scar site, with a muscular layer thickness

Univariate and multiple logistic regression analysis were used to examine the relationship between variables and the risk of postoperative hemorrhage during hysteroscopy for CSP. SPSS 25.0 statistical software (IBM Corp., Chicago, IL, USA) was used for analysis. Measurement data were expressed as

The factors of age, number and years of previous cesarean sections, number of induced abortions, hCG level prior to treatment, and CSP classification were not significantly associated with the risk of hemorrhage during hysteroscopic treatment of CSP (Table 1). However, the number of amenorrhea days, gestational sac length, myometrial thickness of the uterine scar, and blood flow signal around the gestational sac were all significantly associated with the risk of hemorrhage (p

| Clinical feature | Hemorrhage volume | p | ||

| Group A | Group B | |||

| Frequency of cesarean section | 0.4221 | |||

| 1 | 61% (183/300) | 68.4% (26/38) | ||

| 2 | 35.7% (107/300) | 31.6% (12/38) | ||

| 3 | 3.3% (10/300) | 0% (0/38) | ||

| CSP classification | ||||

| I | 45.7% (137/300) | 55.3% (21/38) | 0.2321 | |

| II | 45.7% (137/300) | 31.6% (12/38) | ||

| III | 8.6% (26/300) | 13.2% (5/38) | ||

| Blood flow signal | 0.0011 | |||

| H | 8% (24/300) | 28.9% (11/38) | ||

| L | 92% (276/300) | 71.1% (27/38) | ||

| Interval time of cesarean section | 5 (3, 8) | 5 (3, 9.25) | 0.4603 | |

| Number of abortions | 2 (1, 3) | 2 (1, 3) | 0.1753 | |

| Gestational sac length (mm) | 30.50 (21.25, 42.00) | 45.00 (35.00, 52.75) | 0.0013 | |

| Days of amenorrhea | 49 (43, 59) | 57 (50, 74.25) | 0.0013 | |

| hCG (mmol/mL) | 47,732 (17,866, 14,582) | 59,043 (11,415, 151,272) | 0.6393 | |

| Age (years) | 33.14 | 32.24 | 0.2292 | |

| Thickness of uterine scar (mm) | 2.40 (1.30, 4.00) | 0.95 (0.00, 1.93) | 0.0013 | |

1 Chi-square test; 2 t-test; 3 Mann-Whitney U rank-sum test. hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin.

As shown in Table 1, the amenorrhea period with different bleeding volumes was 49.00 (43.00, 59.00) vs. 57.00 (50.00, 74.25), with statistical differences (p = 0.001). The diameter of gestational sac (mm) was 30.50 (21.25, 42.00) and 45.00 (35.00, 52.75), respectively, with a p value of 0.001, indicating statistical differences. The thickness of uterine scar (mm) was 2.40 (1.30, 4.00) and 0.95 (0.00, 1.93), respectively, with a p value of 0.001, indicating statistical differences (see Table 2).

| Factor | p | OR | 95% CI |

| Amenorrhea days | 0.001 | 1.036 | 1.015–1.058 |

| Gestational sac length | 0.016 | 1.027 | 1.005–1.049 |

| Thickness of uterine scar | 0.392 | 0.268–0.573 | |

| Blood flow signal | 0.001 | 4.103 | 1.737–9.691 |

OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

The amenorrhea days were odds ratio (OR) 1.036, with a 95% CI (1.015–1.058), and a p-value of 0.001. The gestational sac length was OR 1.027, with a 95% CI (1.005–1.049), and a p-value of 0.016. The myometrial thickness at the uterine scar was OR 0.392, with a 95% CI (0.268–0.573), and a p-value of

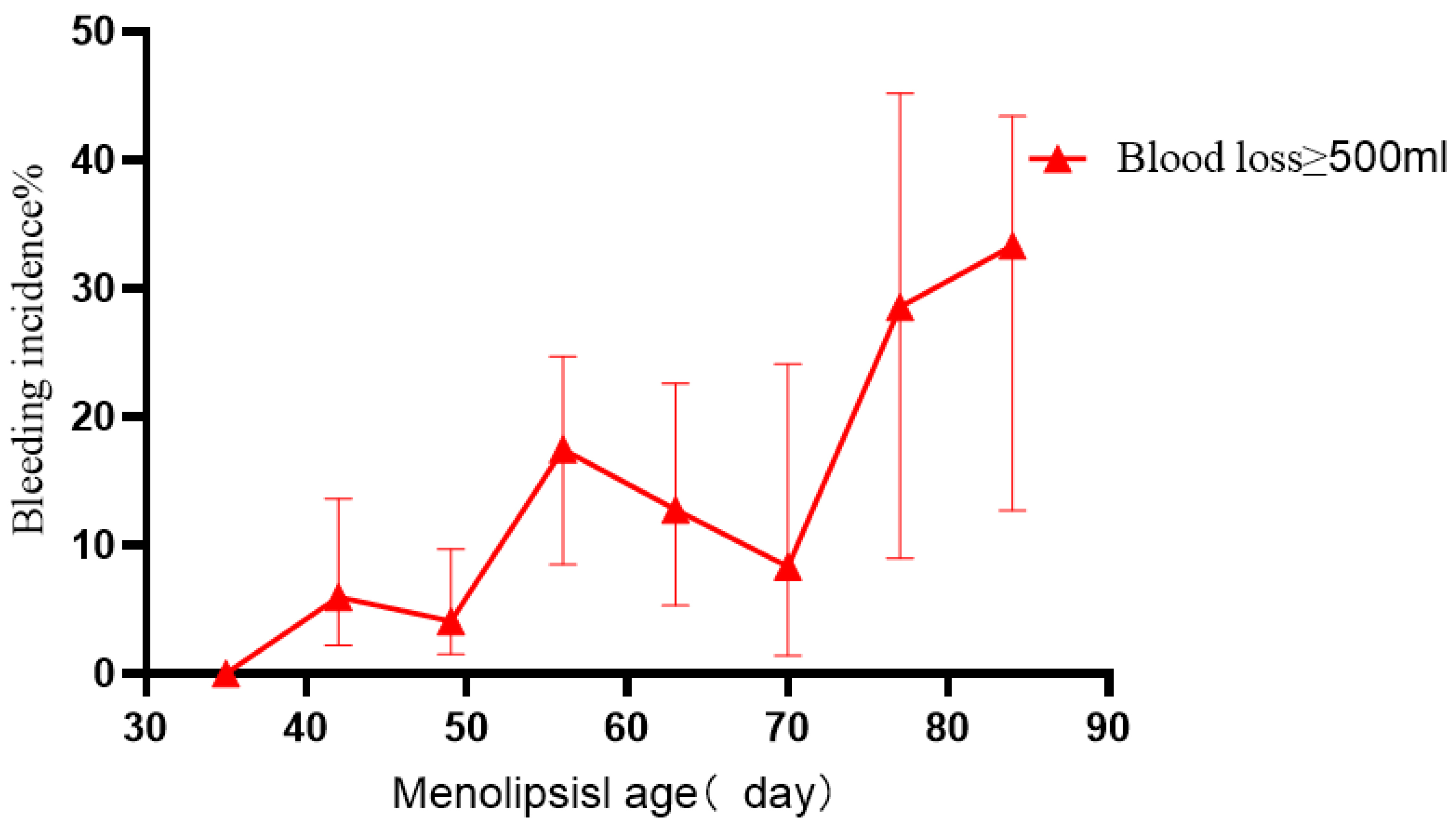

Risk maps for hemorrhage during hysteroscopic treatment for CSP were constructed based on the period of amenorrhea and length of the gestational sac. The risk of hemorrhage from CSP increased after 49 days of amenorrhea, with the incidence of hemorrhage

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Bleeding after hysteroscopic treatment of CSP according to days of amenorrhea.

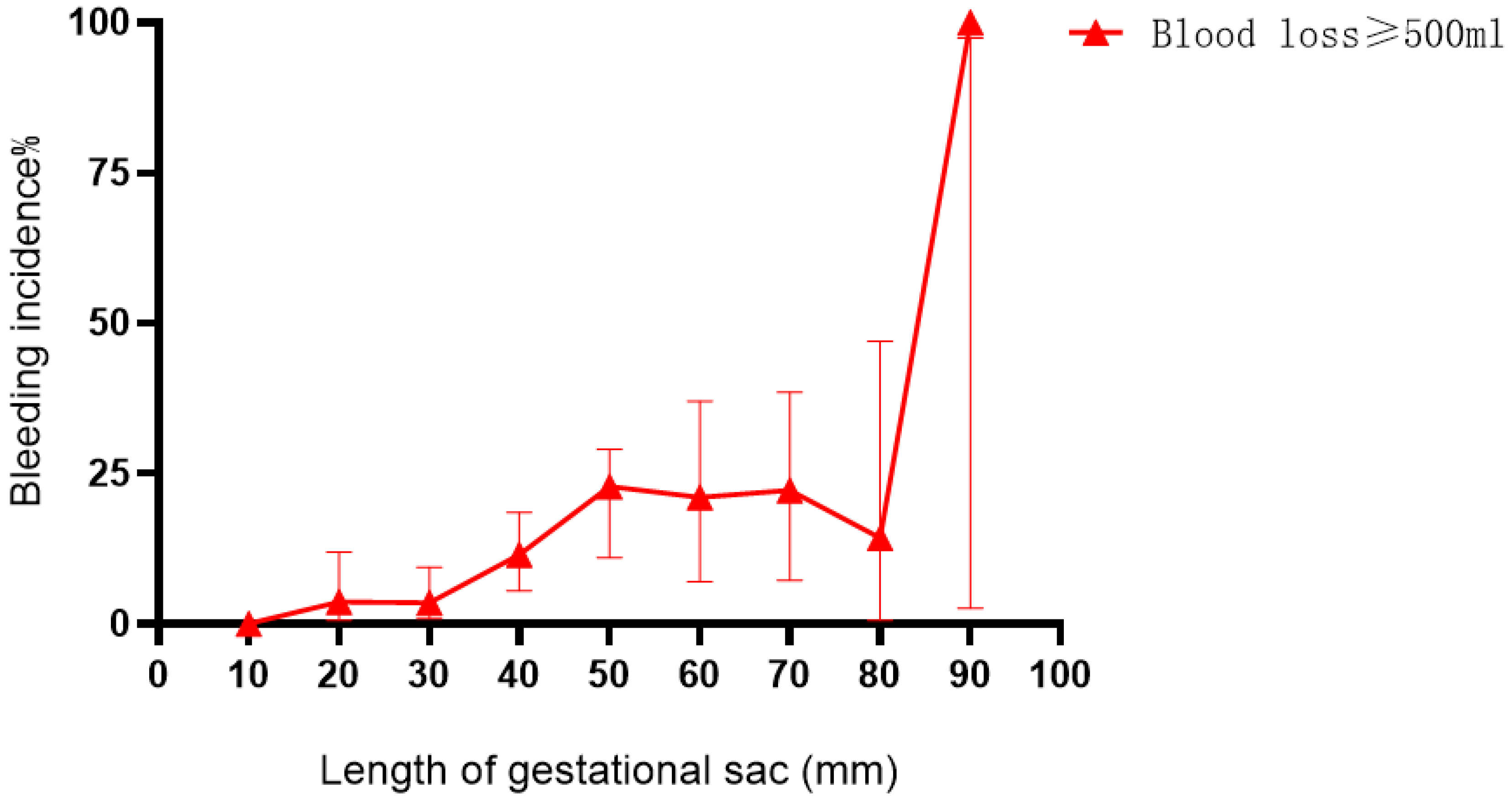

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Bleeding after hysteroscopic treatment of CSP according to the length of the gestational sac.

The error line in Fig. 2 represents the 95% CI. The risk of bleeding was found to increase when the duration of amenorrhea was

Bleeding after hysteroscopic treatment of CSP increased when the gestational sac length was

CSP is rare ectopic pregnancy that occurs at a specific location. Severe complications, such as massive hemorrhage and uterine rupture, may occur with continuing pregnancy or after surgical intervention [5]. The basic principles and methods for reducing morbidity should be followed as closely as possible in order to preserve patient fertility [6]. Due to the implementation of the two-child policy in China, CSP is becoming more common. As the number of gestational days increases, severe complications from CSP may occur, including uterine rupture, massive hemorrhage, and even life-threatening situations [7]. In this retrospective analysis, 338 patients with CSP were treated by hysteroscopy. None of the patients required additional treatments because of severe bleeding (e.g., hysterectomy). Hysteroscopic curettage has several advantages compared to other methods, including that it is direct, rapid, intuitive, low cost, and has no subsequent adverse complications. Moreover, it has been reported that pregnancy after a hysteroscopic operation has favorable outcomes [8]. According to the literature, not all patients are suitable for hysteroscopy, and the completion rate of hysteroscopic surgery for CSP is reported to be 50–80% [9]. The selection of suitable patients, as well as the timely execution of this procedure, are important for the successful outcome of CSP treatment by hysteroscopy in clinical practice.

The treatment principle is early diagnosis, prompt intervention, and timely resolution. We analyzed several factors that could potentially increase the risk of hemorrhage after hysteroscopic treatment of CSP, including patient age, days of amenorrhea, frequency and interval time of cesarean section, number of abortions, thickness of the myometrium at the uterine scar, hCG level prior to treatment, length and type of gestational sac, and blood flow signal around the gestational sac. Our study found that high-risk factors for hysteroscopic curettage included the duration of amenorrhea, gestational sac length, myometrial thickness of the uterine scar, and blood flow signal around the gestational sac. These findings should allow clinicians to better select patients who are suitable for hysteroscopic surgery.

The most significant limitation of hysteroscopic treatment for CSP is the occurrence of massive hemorrhage [10, 11]. Study that has systematically analyzed the effectiveness and safety of CSP treatment have defined massive hemorrhage as a volume

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the factors associated with hemorrhage after hysteroscopic surgery for CSP. Curettage of CSP lesions by hysteroscopy was deemed safe and feasible when the duration of amenorrhea was

The data and materials that support the findings of this study are available from the first author.

QY and CL designed the research study. CL and XX performed the research. CL provided help and advice on the article. QY analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Chongqing Medical University (approval number: 2022 scientific research ethics (2020-531)). All patients provided informed consent prior to the operation.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest. Cong Li is serving as one of the Editorial Board members of this journal. We declare that Cong Li had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Michael H. Dahan.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.