1 Department of Radiophysics, Zhejiang Cancer Hospital, 310022 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

2 Department of Gynecological Radiation Therapy, Zhejiang Cancer Hospital, 310022 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

Abstract

Continuous advancements in comprehensive tumor treatment strategies have significantly improved survival rates of patients. The ovary is a crucial organ essential for maintaining women’s quality of life and fertility. Safeguarding ovarian function during radiotherapy for cervical cancer has become a prominent focus of current clinical research. The aim of this study is to explore the key factors involved in ovarian protection during radiotherapy for cervical cancer.

This study involved a comprehensive analysis of literature from 2015 to 2024 on ovarian function preservation during radiotherapy for cervical cancer, to identify technical trends. Additionally, patient data from Zhejiang Cancer Hospital from 2011 to 2018 was collected, focusing on patients who underwent radiotherapy to preserve ovarian function. Specifically, data from 10 patients with IA–IIB stage cervical cancer who underwent bilateral ovarian transposition (OT) and radiotherapy at our hospital between 2016 and 2018 was analyzed. Intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT), and helical tomotherapy (HT) radiotherapy plans will be design for these patients to evaluate strategies for optimal ovarian protection. The optimal radiotherapy plan was determined through comparisons of dosimetric parameters.

(1) A literature review indicated that only 24 detailed reports on ovarian protection during cervical cancer radiotherapy have been published in the past 10 years. It has been established that ovarian protection presents a positive significance for cervical cancer patients, with OT being a necessary condition. Nevertheless, no standardized unified dose limit for ovarian radiation has been established. (2) After screening, a total of 77 patients with complete follow-up data from 2011 to 2018 were selected for the study. Following serum hormone level tests, 73 patients presented normal ovarian function prior to radiotherapy, while 4 demonstrated signs of impaired function. Three months after radiotherapy, 26 patients maintained normal ovarian function, 13 exhibited impaired function, and 38 showed a decline in function. One year later, 45 patients maintained normal ovarian function, 13 had impaired function, and 19 experiences further deteriorated function. The overall success rate amounted to 75.3%, and favorable clinical outcomes were observed. (3) Compared to IMRT and VMAT, HT reduced the maximum dose (Dmax) of the right ovary and demonstrated dosimetric advantages in terms of Dmax of the planning target volume (PTV), as well as in 30 Gy (V30) and 40 Gy (V40) of the bladder, and Dmax of the spinal cord. These differences were statistically significant. Compared with HT, IMRT and VMAT had advantages in the minimum dose (Dmin) of PTV and the mean dose (Dmean) of the left femoral head, and the differences were statistically significant. Compared with VMAT, most dosimetric results of IMRT were similar and the differences were not statistically significant, but IMRT had an advantage in the conformity index (CI) of PTV (p = 0.016).

Following receiving a certain radiation dose, the ovaries may undergo a temporary functional decline or even complete failure. The key to protecting the ovarian function during cervical cancer radiotherapy lies in successful OT, precise delineation of ovarian tissue, determination of dose limits for patients across different age groups, as well as the application of HT and specialized IMRT techniques.

Keywords

- radiotherapy for cervical carcinoma

- ovarian conservation

- plan design

- dosimetry

Cervical cancer is the fourth most prevalent cancer among women worldwide, with approximately 600,000 new cases diagnosed each year, and its incidence continues to rise [1]. There is also a growing trend of cervical cancer occurring in younger patients, with approximately 30%–40% of cases occurring in women of reproductive age [2]. Continuous advancements in comprehensive cancer treatments, such as surgery and radiotherapy, have significantly improved survival rate, leading to higher expectations for the quality of life among cancer patients. The ovary is situated in the pelvis, in close proximity to the target area of cervical cancer tumors [3]. Inevitably, it will be exposed to a certain dose of radiation during radiotherapy, causing varying degrees of damage to ovarian function [4]. Premature ovarian dysfunction can result in the loss of fertility, while ovarian decline may lead to premature menopause, hot flashes, osteoporosis, and even cardiovascular complications [5]. The overall consequence of ovarian function decline or failure may include a significant decrease in quality of life and, in some cases, premature death.

Ovarian tissue is highly sensitive to radiation. Wallace et al. [6] used a model to predict that a radiation dose of approximately 2 Gy necessary to cause the closure of 50% of the ovarian follicles in women of reproductive age, which they defined as the Lethal Dose, 50% (LD50) for human ovarian tissue. Higher doses of radiation can directly result in the loss of female fertility. The dose required for this decreases with age, being approximately 20.3 Gy at birth, 18.4 Gy at the age 10, 16.5 Gy at the age 20, and 14.3 Gy at age 30 [7]. Yamamoto et al. [8] found that the probability of ovarian metastasis in early-stage cervical squamous cell carcinoma was only 0.4%, whereas the overall probability of ovarian metastasis in non-cervical squamous cell carcinoma was 8.5%. A systematic review and meta-analysis found that preserving the ovaries had no significant influence on the prognosis of young patients with early cervical adenocarcinoma [9]. Therefore, preserving the ovaries in patients with early cervical cancer is both safe and feasible.

The methods for protecting the ovaries during cervical cancer radiotherapy mainly consist of three approaches: (1) biological protection approaches, such as embryo cryopreservation, oocyte cryopreservation, ovarian tissue cryopreservation and transplantation [10]; (2) chemical protection methods, primarily involving the application of radiation-resistant drugs [11]; and (3) physical protection methods, such as ovarian transposition (OT), which involve transplanting the ovaries to a site distant from the target area to reduce radiation exposure and protect ovarian function [12]. Biological and chemical protection methods are restricted by contraindications, and the related technologies are not yet fully developed, resulting in limited accessibility [13]. OT has been refined through clinical practice and has become a standard technique, being the key method for protecting the ovaries during cervical cancer radiotherapy. Jung et al. [14] investigated the effect of preserving ovarian function in cervical cancer patients by performing OT prior to pelvic radiotherapy. They found that the 5-year ovarian survival rate in patients who underwent OT treatment was 60.3%, whereas all patients who did not receive OT treatment experienced ovarian dysfunction.

The dose received by the ovaries during radiotherapy is closely related to their position, the target area, the radiotherapy regimen, the distribution of the target area, and the techniques used in radiotherapy. Ensuring adequate coverage of the target area while limiting the radiation dose to the ovaries poses a significant challenge in clinical radiotherapy. Advancements in radiotherapy technologies, such as intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT), volumetric modulated arc therapy (VMAT), helical tomotherapy (HT), carbon ion therapy, and proton radiotherapy, have made ovarian protection feasible during cervical cancer treatment. However, the key challenge in clinical practice is determining appropriate dose limit for the ovaries and achieving it using various radiotherapy techniques. This study was conducted in three main aspects: (1) a literature analysis was conducted to identify recent technical trends in ovarian protection during cervical cancer radiotherapy; (2) the relationship between ovarian function preservation and ovarian dose limit was established based on clinical cases and follow-up data from our hospital; and (3) radiotherapy treatment plans using IMRT, VMAT, and HT were designed, and the optimal treatment plan was identified through dosimetric comparisons. This study addresses several key issues in ovarian protection during cervical cancer radiotherapy, providing guidance for clinical practice.

A comprehensive search was conducted in the PubMed database and the Chinese Core Journal Database using a range of relevant keywords, such as “cervical cancer irradiation”, “pelvic radiation therapy”, “ovarian function”, “ovarian transposition”, “gynecological cancer irradiation”, “fertility preservation”, “cervical cancer radiotherapy”, “ovarian protection”, and “reproductive function preservation”. The retrieved literature spans from 2015 to 2024 and focuses on strategies aimed at preserving ovarian function during cervical cancer radiotherapy. This study provides insights into current technical trends, encompassing procedures for OT, precise delineation of the ovarian region, the establishment of appropriate dose limits for the ovaries, as well as the application of various radiotherapy techniques.

A study conducted at Zhejiang Cancer Hospital between 2011 and 2018 assessed the ovarian function of cervical cancer patients who underwent radiotherapy. The study included women who had undergone bilateral or unilateral oophoropexy prior to radiation therapy. Following surgery, serum hormone levels were measured three months post-radiotherapy and again one year after treatment. The dataset included 77 patients with complete follow-up records. The patients’ age ranged from 24 to 45 years, with a median age of 35 years and a mean age of 35.5

Data were compiled from all 10 young cervical cancer patients who underwent bilateral ovarian protective radiotherapy at Zhejiang Cancer Hospital between January 2016 and August 2018. Pre-treatment procedures included cervical cancer resection and bilateral ovarian displacement prior to radiotherapy initiation. The patients’ ages ranged from 26 to 38 years, with a median age of 34 years. Among them, 8 were diagnosed with squamous cell carcinoma, while 2 were diagnosed with adenocarcinoma. According to the FIGO 2018 staging criteria, 2 cases were classified as stage IA, 4 as stage IIA, 1 as stage IB, and 3 as stage IIB. All patients received external irradiation for radiotherapy, 7 patients were treated with IMRT plans, while 3 received HT plans. The prescribed dose consisted of a single fraction of 180 cGy, administered over 25 fractions. Normal ovarian endocrine function was confirmed through hormone examination prior to initiating radiotherapy.

All patients were positioned supine, immobilized in the abdominal and pelvic regions, and instructed to consume 500 mL of mineral water 1 hour prior to scanning to ensure optimal bladder filling. The simulation was performed using a Philips Brilliance™ 16 (Amsterdam, Netherlands) large aperture CT simulator with a slice thickness of 5 mm, covering from the upper edge of the second lumbar vertebra to 5 cm below the ischial tuberosity. Subsequently, the CT images were transferred to the treatment planning system for further analysis. The clinical target volume (CTV) was delineated following postoperative pelvic delineation guidelines provided by the US Radiation Treatment Oncology Group (RTOG) for cervical cancer [16].

The CTV includes anatomical structures within the upper portion of the vaginal segment, encompassing the vaginal stump, paravaginal tissue, and pelvic lymphatic drainage region. The superior demarcation point for lymph nodes is defined of the level of fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae, while the inferior limit corresponds to the level of osseous closure. Additionally, the CTV encompasses regions such as the cervical myometrium and the presacral lymphatic drainage territory. To define the planning target volume (PTV), an additional 1 cm margin was added around the CTV. The organs at risks (OARs), including the rectum, bladder, pouch, bone marrow, spinal cord, ovaries, and bilateral femoral heads, were delineated with a 2 cm extending beyond the PTV boundaries. This included all segments of the small intestine, colon, sigmoid colon, the upper rectum up to the rectosigmoid junction, and the lower rectum down to the anus. The bladder was contoured in its entirety, while the fourth and fifth lumbar vertebrae, along with sacrum and iliac bone were included for bone marrow delineation. The ovaries were outlined considering soft tissue shadow between silver clip marks, while the left and right femoral heads were delineated separately.

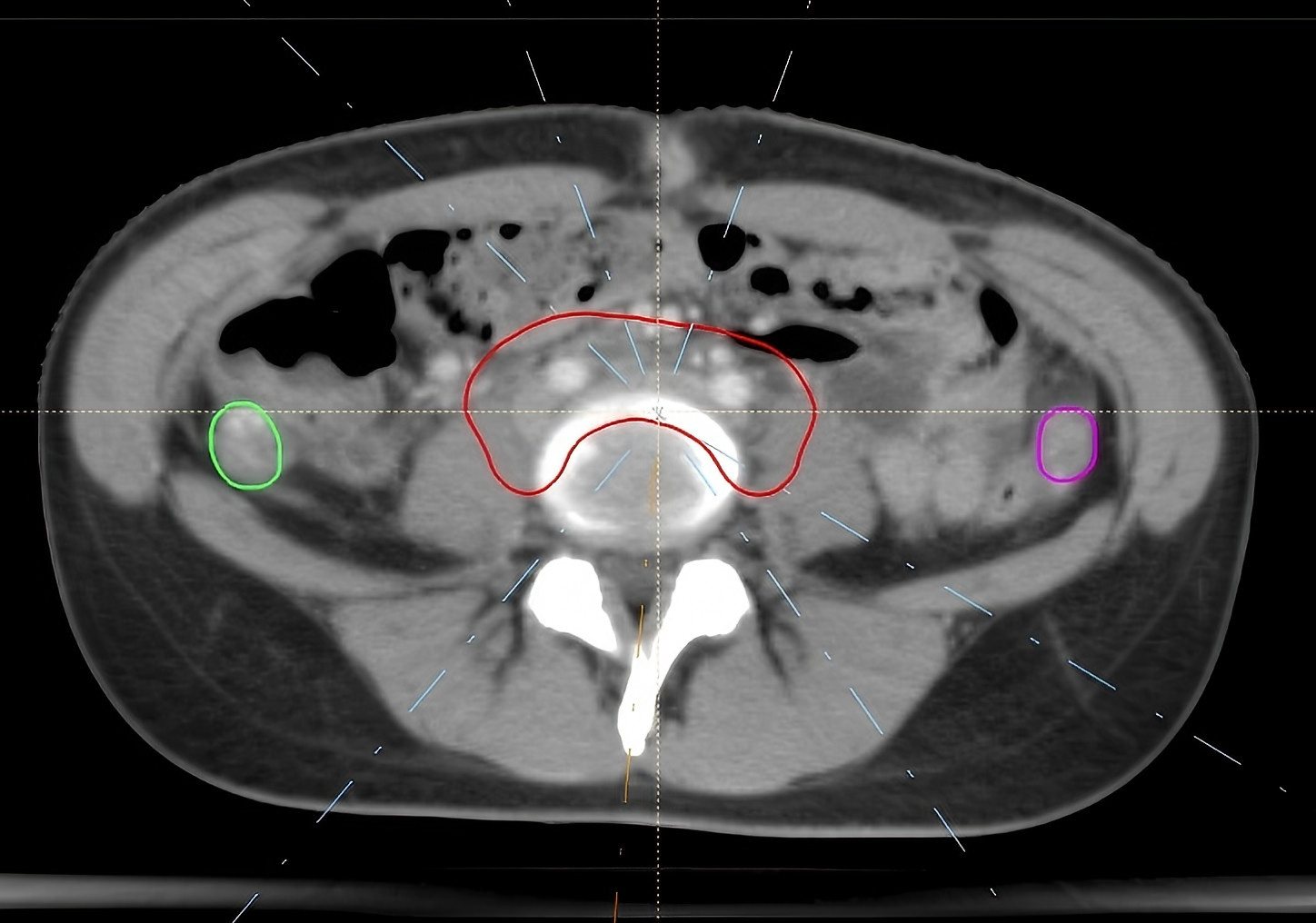

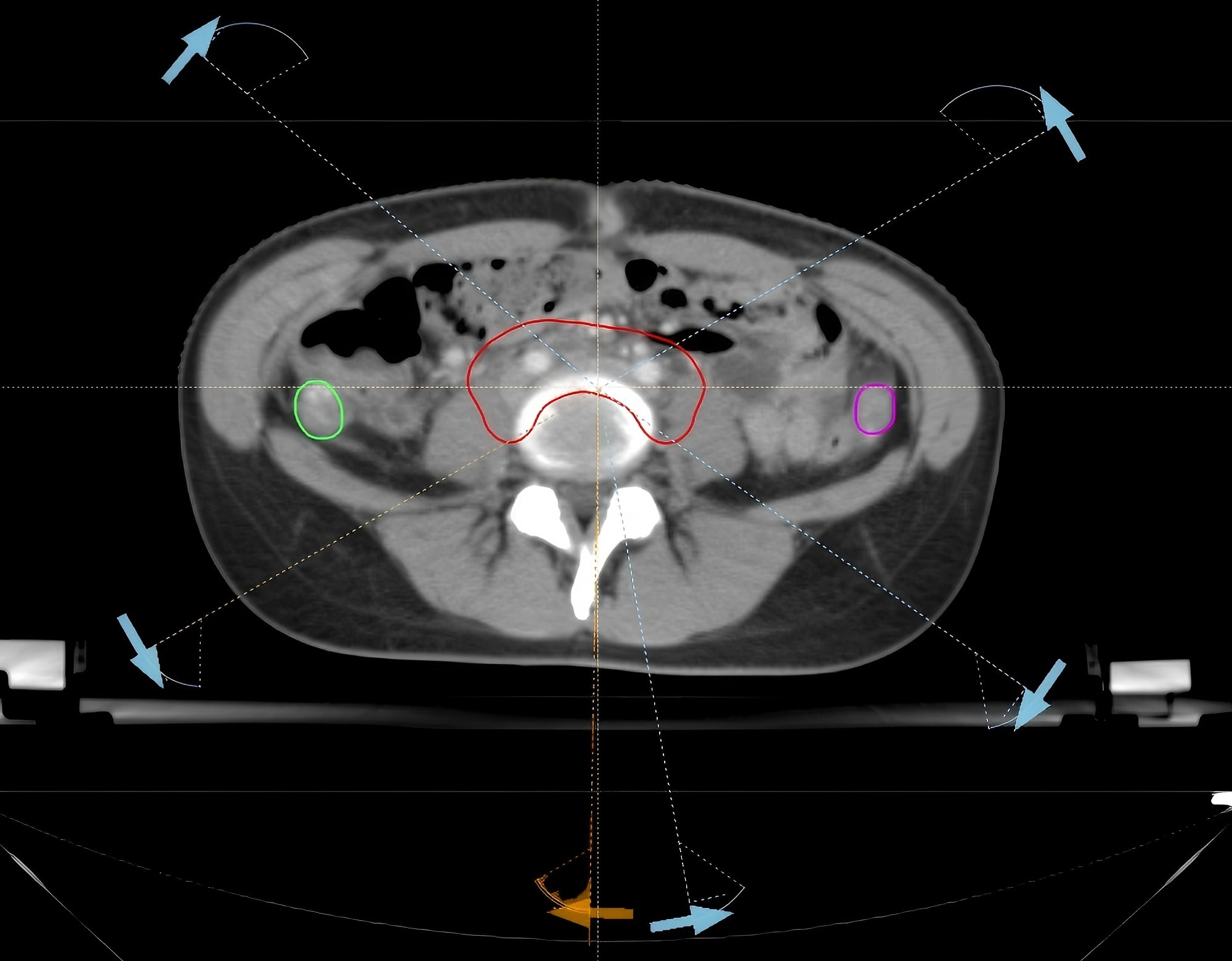

IMRT treatment was administered to 7 patients, while 3 patients received HT. The treatment plans for each patient included three radiotherapy techniques: IMRT, VMAT, and HT. A total of 30 plans were made for the 10 cases. A prescribed dose of 45 Gy was delivered in fractions of 1.8 Gy. The IMRT and VMAT plans were generated using the RayStation version 4.0 (RaySearch Labor, Stockholm, Sweden), while the HT plans were created with the TomoHelical™ version 2.0 (Accuracy Inc, Madison, WI, USA). The IMRT plans employed 6 MV X-rays with a 7-field coplanar technique, optimizing the gantry angles to avoid the ovaries. The primary objective was to exclude the ovaries from the beam’s eye view (BEV) shooting field, resulting in a total of 70 segments, as show in Fig. 1. Similarly, for the VMAT plan, 6 MV X-rays were utilized, and treatment was divided into three double arcs based on ovarian positioning. The angle settings were optimized to minimize the overlap between the ovaries and the field in the BEV direction, with a 2-degree interval, as shown in Fig. 2. For the HT plan, a field width (FW) of 2.5 cm, a pitch of 0.43, and a modulation factor (MF) of 2 were selected, along with a fine dose calculation grid. The ovaries were positioned in half-beam mode.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. IMRT field arrangement. IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy. The red structure is the planning target volume (PTV), while the green and rose-pink ones are the left and right ovaries respectively. The white dotted line represents the central axis of the radiation field.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. VMAT field arrangement VMAT. VMAT, volumetric modulated arc therapy. The red structure is the PTV, while the green and rose-pink ones are the left and right ovaries respectively. The white dotted line marks the boundary of the VMAT radiation field.

The dosimetric constraints for the plans were as follows: (1) at least 95% of the PTV should receive the prescribed dose of 45 Gy, with less than 0.03 cm3 of the volume exceeding 115% of the prescribed dose; (2) a minimum of 99% of the CTV must receive the prescribed dose of 45 Gy; (3) the maximum dose (Dmax) to the spinal cord should not exceed 45 Gy; (4) for the bladder, rectum, and bowel bag, the minimum dose received by 2 cm3 (D2cc) should be below 50 Gy, with the volume receiving 40% of prescribed dose (V40) for bladder being less than 70%, for the rectum being less than 100%, for the bowel bag being less than 70%, and absolute volume receiving 45 Gy (V45) being below 195 cm3; (5) for the bone marrow, the percentage volumes receiving doses of 10 Gy (V10) and 20 Gy (V20) should be below 85% and 70%; and (6) the mean dose (Dmean) to be femoral heads should be below 14 Gy, and the Dmax and Dmean to the ovaries should be below 5 Gy and 3 Gy, respectively.

The IMRT, VMAT, and HT plans were assessed by analyzing isodose curves and dose-volume histogram (DVH) using the RayStation version 4.0 and TomoHelical™ systems, respectively. The Dmax, minimum dose (Dmin), Dmean, conformity index (CI), and homogeneity index (HI) of the PTV were documented.

Serum concentrations of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and estradiol (E2) were assessed prior to radiotherapy and during the post-treatment period at both three-months and one-year mark. Approximately five milliliters of venous blood were collected at around 7:00 AM on the third day of each patient’s menstrual cycle. Climacteric symptoms were evaluated, and corresponding serum FSH and E2 concentrations were monitored throughout the treatment duration when symptoms were present. Ovarian function was assessed based on specific criteria: patients without perimenopausal symptoms alongside serum FSH concentrations below 40 international units per liter (

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 22 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). The normality of the data was examined through the Shapiro-Wilk test. When the data followed a normal distribution, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) test was performed to compare the differences. When the data did not follow a normal distribution, the Kruskal-Wallis test was performed. Quantitative data were expressed as the mean

Over the past decade, a total of 24 comprehensive reports on ovarian protection in cervical cancer patients undergoing radiotherapy have been published, as detailed in Table 1 (Ref. [4, 14, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41]).

| Author and year | Main ideas |

| Soda et al., 2015 [20] | The PRV margin for the transposed ovary was set to 2 cm in all directions. |

| Rousset-Jablonski et al., 2016 [21] | IMRT combined with OT can preserve fertility function. |

| Du et al., 2017 [22] | Limiting the ovarian radiation dose to V7.5 |

| Yoshihiro et al., 2018 [23] | To reduce the Dmean of the ovary to less than 3 Gy, the ovaries should be transposed laterally 6.1 cm away from the PTV surface when using VMAT. |

| Hoekman et al., 2018 [24] | OT prior to pelvic radiation is effective in women up to the age of 35 years and should be considered in patients aged 36–40 years. |

| Yin et al., 2019 [25] | An ovarian Dmax of |

| Lv et al., 2019 [26] | When the transposed ovary is positioned below the upper boundary of PTV, an ovarian Dmax |

| Costa-Roig et al., 2020 [27] | OT is a feasible and safe technique. However, patients require extended follow-up to assess ovarian function after oncological treatment. |

| Guo et al., 2021 [28] | When the ovary was located above the PTV, the Dmean of the ovary for IMRT and VMAT was (177.8 |

| Marchocki et al., 2021 [29] | It is recommended to move the bilateral ovaries to the upper abdomen through high laparoscopy, transposing and securing ovaries above the inferior liver edge on the right and above the splenic flexure on the left. |

| Laios et al., 2021 [30] | OT should be performed in pre-menopausal women with cervical cancer undergoing pelvic irradiation, irrespective of their desire for fertility, to preserve ovarian function and prevent early menopause. Menopause is not an indication for OT. |

| Jung et al., 2021 [14] | The 5-year ovarian survival rate was 60.3% in patients who underwent OT before RT. Patients who received RT without OT experienced ovarian failure, while the OT procedure itself did not affect the occurrence of ovarian failure. |

| Gross et al., 2021 [31] | Proton therapy is a viable radiation strategy for fertility preservation. |

| Xu et al., 2021 [32] | When the distance between the center of a transposed ovary and the PTV margin was |

| Gay et al., 2021 [4] | Unilateral or bilateral OT was performed prior to radiation therapy. The amount of the 10 Gy isodose line within the ovary contour should be limited in at least one ovary using 3D-CRT or IMRT. |

| Gill et al., 2022 [33] | For patients |

| Anderson et al., 2022 [34] | Anti-Müllerian hormone was used to identify the damaging effects of cancer treatments on ovarian function. |

| Kelsey et al., 2022 [35] | A curve relating a woman’s age to the average effective dose to the ovaries was constructed, which can be utilized to establish clinical reference dose limits for ovarian radiation therapy. |

| Huang et al., 2023 [36] | Ovarian-sparing IMRT plans with ovarian protection successfully reduced the ovarian dose while meeting the D95% target prescription requirements, thereby significantly reducing ovarian radiation toxicity. |

| Dong et al., 2023 [37] | The Dmean to the ovary in coplanar and noncoplanar IMRT plans was 731 cGy and 680 cGy, respectively, with the noncoplanar design effectively reducing the dose to the ovary. |

| Ma et al., 2023 [38] | Human oocytes are highly sensitive to radiation. With advanced age, the effective radiation dose that causes premature ovarian failure decreased. The maximum tolerated dose for the ovaries is 16.5 Gy at age 20, 14.3 Gy at age 30, and only 6 Gy at age 40. For women in their 30s, a radiation dose of 5–10 Gy can induce menopause, while for those over 40, a dose of 3.75 Gy may cause ovarian failure. VMAT and HT are recommended for ovarian-sparing. |

| Barcellini et al., 2024 [39] | Carbon ion radiotherapy can limit the ovaries’ Dmean to 51 cGy, offering better protection for the ovaries. |

| Luan et al., 2024 [40] | Deep learning was used to predict the dose distribution for cervical cancer, assisting clinicians in performing OT surgery. |

| Hill-Kayser et al., 2024 [41] | Precise delineation of ovarian structures and limiting the average dose received by the ovaries are crucial for ovarian protection. The doses to the uterus and vagina should also be limited. |

Note: IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; VMAT, volumetric modulated arc therapy; PTV, planning target volume; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; Dmean, mean dose; Dmax, maximum dose; PRV, planning organ at risk volume; HT, helical tomotherapy; OT, ovarian transposition; OAR, organs at risk; RT, radiotherapy; LOF, loss of ovarian function; 3D-CRT, three-dimensional conformal radiation therapy.

Hormone level test results for serum: prior to radiotherapy, 73 individuals exhibited normal hormone levels, while 4 showed a decrease. Three months post-radiotherapy, 26 individuals maintained hormone levels within the normal range, 13 displayed a decrease, and 38 experienced hormonal failure. One year after radiotherapy, 45 individuals sustained normal hormone levels, 13 exhibited a decrease, and 19 experienced hormonal failure. The results were classified into three categories: normal group, declining group, and exhausted group.

According to the data analysis, only the ovary Dmean followed a normal distribution in all three groups, while the other parameters did not fully conform to a normal distribution. The ANOVA test and Kruskal-Wallis test were performed separately to compare the differences. Further details regarding ovarian function and other related information can be found in Table 2. No significant differences were observed in age, BMI, ovary Dmax, and ovary Dmean among the three groups.

| Normal group | Declining group | Exhausted group | Analysis result | |

| Age (years) | 35.00 (32.00, 37.00) | 39.00 (34.50, 40.50) | 36.00 (34.00, 39.00) | H = 5.670, p = 0.059 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 20.96 (19.50, 22.54) | 20.20 (19.77, 13.92) | 20.43 (18.49, 22.06) | H = 1.181, p = 0.554 |

| Ovary Dmax/cGy | 387.00 (353.50, 434.00) | 385.00 (362.00, 425.00) | 405.00 (369.00, 483.00) | H = 1.385, p = 0.500 |

| Ovary Dmean/cGy | 272.69 | 278.84 | 287.84 | F = 0.462, p = 0.632 |

Notes: BMI, body mass index; Dmean, mean dose; Dmax, maximum dose. p

The radiation dosage administered during radiotherapy for cervical cancer exhibits a positive correlation with tumor displacement and its proximity to the PTV edge [42]. This study encompassed the calculation of geometric parameters for both PTV and OARs, as well as an evaluation of the positioning of the ovaries and PTV in relation to the iliac crest, within a cohort of 10 patients. The detailed findings are presented in Table 3 below.

| Cases | Volume/cm3 | Closest distance to the PTV (cm) | Distance from ovary to iliac crest (cm) | ||||

| PTV | OL | OR | OL | OR | OL | OR | |

| 1 | 1291.52 | 12.84 | 12.47 | 3.31 | 2.89 | 2.61 | 5.09 |

| 2 | 1199.96 | 20.40 | 13.78 | 6.03 | 4.02 | 2.16 | –0.50 |

| 3 | 1168.22 | 9.90 | 13.41 | 2.83 | 4.98 | –0.50 | 4.31 |

| 4 | 1172.87 | 11.67 | 17.32 | 3.60 | 3.30 | –1.01 | 3.09 |

| 5 | 914.81 | 9.81 | 25.58 | 2.23 | 3.32 | –3.69 | –1.47 |

| 6 | 880.81 | 6.98 | 5.49 | 2.42 | 3.16 | –2.75 | –1.53 |

| 7 | 1046.53 | 10.41 | 14.27 | 4.91 | 3.87 | 0.35 | –0.47 |

| 8 | 975.64 | 4.70 | 8.69 | 2.89 | 4.76 | –1.95 | 0.11 |

| 9 | 1111.71 | 25.74 | 5.98 | 3.53 | 4.28 | –0.21 | 2.32 |

| 10 | 888.16 | 18.71 | 18.24 | 2.20 | 2.42 | –3.71 | 0.12 |

| Mean | 1065.02 | 13.12 | 13.52 | 3.40 | 3.70 | –0.87 | 1.11 |

Notes: OL, ovary left; OR, ovary right; SD, standard deviation; PTV, planning target volume. When the ovary is positioned above the iliac crest, the distance value is positive; conversely, when it is located below the iliac crest, the distance value is negative.

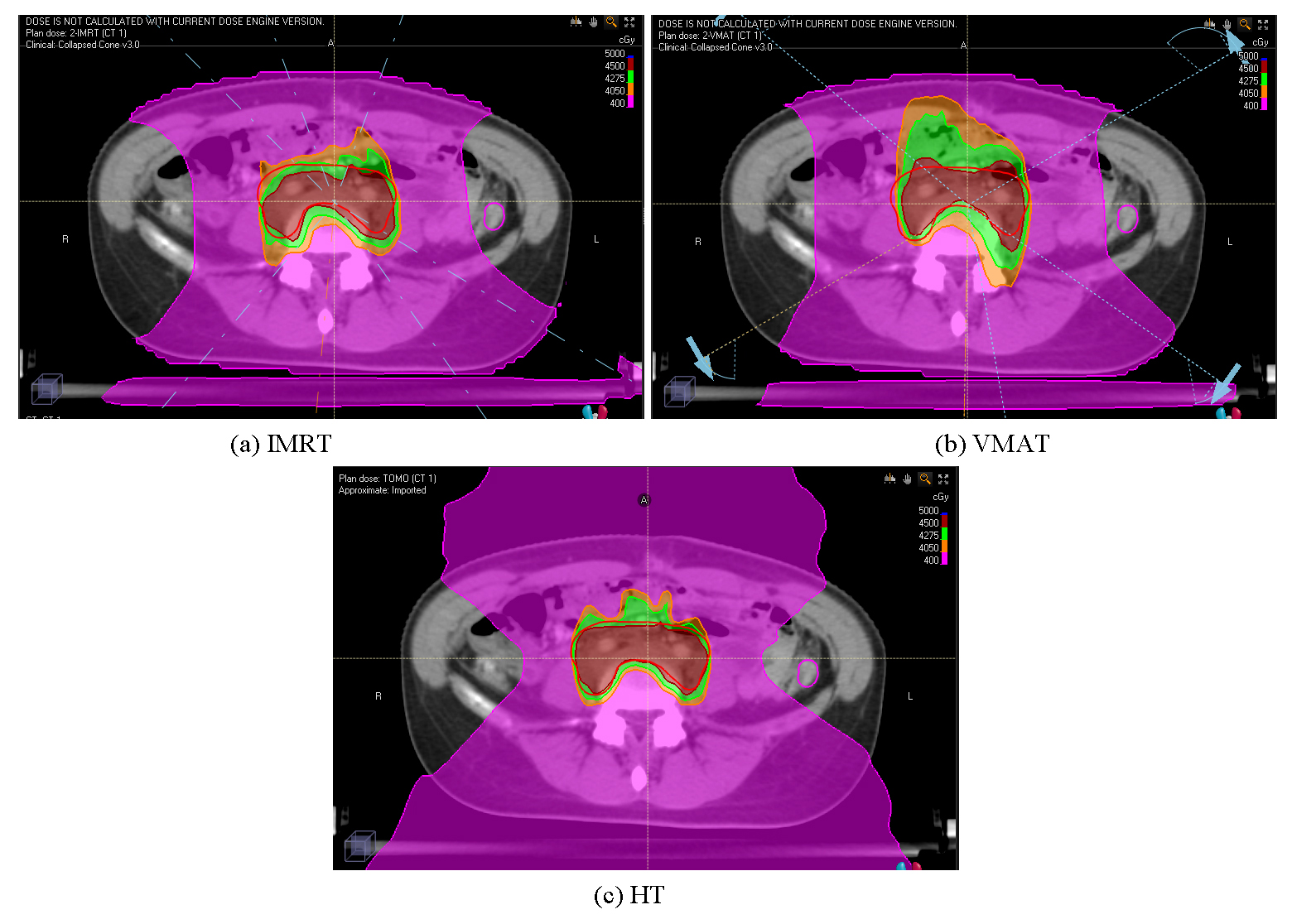

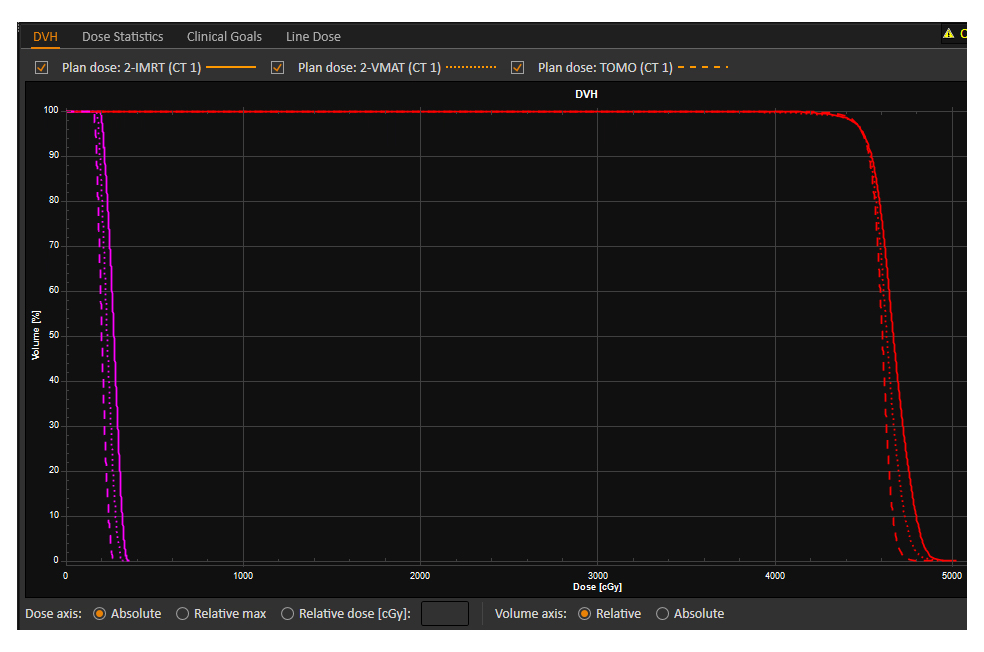

All IMRT, VMAT, and HT plans were designed to minimize the dose to the ovaries while fulfilling the dosimetric requirements for PTV and OARs. The dose distribution and DVH curves for the three plans are presented in Figs. 3,4. The planning parameters for each plan were recorded separately.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Dosimetric distribution of the three treatment plans: IMRT (a), VMAT (b), and HT (c). IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; VMAT, volumetric modulated arc therapy; HT, helical tomotherapy.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. The DVH of the three treatment plans: IMRT, VMAT, and HT. DVH, dose-volume histogram; IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; VMAT, volumetric modulated arc therapy; HT, helical tomotherapy. The red DVH curve represents the PTV, and the rose red DVH curve represents the left ovary.

The dosimetric parameters of the PTV for the three treatment plans are presented in Table 4.

| IMRT | VMAT | HT | Analysis result | |

| Dmax/Gy | 50.39 | 50.38 | 49.01 | F = 7.284, p = 0.003* |

| Dmean/Gy | 46.59 | 46.68 | 46.91 | F = 1.043, p = 0.366 |

| Dmin/Gy | 43.74 | 42.85 | 33.23 | F = 30.629, p |

| HI | 0.094 | 0.103 | 0.092 | F = 0.752, p = 0.481 |

| CI | 0.850 | 0.791 | 0.848 | F = 5.918, p = 0.007* |

Note: *, p

Analysis of the PTV dosimetric parameters for the three groups revealed that they all follow a normal distribution. The differences among the three groups were analyzed through an ANOVA test. Statistically significant differences were observed in PTV Dmax, Dmin, and CI among the IMRT, VMAT, and HT groups (F = 7.284, p = 0.003; F = 30.629, p

The dosimetric parameters of OARs for the three treatment plans are presented in Table 5.

| OARs | IMRT | VMAT | HT | Analysis result |

| OL Dmax/Gy | 4.10 (3.63, 4.53) | 4.75 (3.83, 4.90) | 4.02 (3.59, 4.29) | H = 5.546, p = 0.062 |

| OL Dmean/Gy | 2.47 (2.10, 2.91) | 2.73 (2.58, 3.37) | 2.65 (2.15, 2.84) | H = 1.680, p = 0.432 |

| OR Dmax/Gy | 3.74 | 4.20 | 3.10 | F = 8.394, p = 0.001* |

| OR Dmean/Gy | 2.16 | 2.49 | 1.97 | F = 1.893, p = 0.170 |

| R D2cc/Gy | 46.74 | 46.86 | 47.93 | F = 3.229, p = 0.055 |

| R V30/% | 96.05 (90.83, 98.28) | 93.75 (87.80, 98.35) | 99.25 (92.33, 100.00) | H = 2.246, p = 0.325 |

| R V40/% | 74.49 | 78.15 | 83.25 | F = 0.833, p = 0.446 |

| B D2cc/Gy | 47.85 | 47.85 | 48.21 | F = 0.503, p = 0.610 |

| B V30/% | 88.80 (81.02, 96.95)† | 99.85 (79.50, 100.00)† | 64.50 (57.78, 70.58) | H = 12.943, p = 0.002* |

| B V40/% | 49.20 (44.28, 57.25)† | 67.25 (46.85, 78.38)† | 34.95 (30.37, 38.55) | H = 15.010, p = 0.001* |

| BB D2cc/Gy | 48.14 | 48.35 | 48.19 | F = 0.234, p = 0.793 |

| BB V30/% | 50.79 | 50.27 | 46.16 | F = 0.805, p = 0.458 |

| BB V40/% | 29.25 (25.90, 34.63) | 35.70 (30.48, 37.08) | 25.55 (21.18, 30.55)# | H = 7.837, p = 0.020* |

| BB V45/cm3 | 145.80 | 178.39 | 155.15 | F = 1.771, p = 0.189 |

| BM V10/% | 69.45 | 67.75 | 69.97 | F = 0.342, p = 0.714 |

| BM V20/% | 61.65 (52.28, 62.87) | 61.00 (51.64, 62.01) | 51.50 (47.08, 52.98)# | H = 6.720, p = 0.035* |

| FHL Dmean/Gy | 6.32 | 5.86 | 8.50 | F = 5.021, p = 0.014* |

| FHR Dmean/Gy | 7.06 | 6.90 | 8.37 | F = 2.167, p = 0.134 |

| SC Dmax/Gy | 39.24 (38.05, 40.45)† | 40.56 (39.03, 41.37)† | 37.27 (34.14, 38.03) | H = 15.037, p = 0.001* |

Note: IMRT, intensity-modulated radiation therapy; VMAT, volumetric modulated arc therapy; HT, helical tomotherapy; Dmean, mean dose; Dmax, maximum dose; V10, 10 Gy; V20, 20 Gy; V30, 30 Gy; V40, 40 Gy; D2cc, the minimum dose received by 2 cm3; OAR, organs at risk; OL, ovary left; OR, ovary right; R, rectum; B, bladder; BB, bowel bag; BM, bone marrow; FHL, femoral hea left; FHR, femoral head right; SC, spinal cord. *, p

The dosimetric parameters of OARs were subjected to normal distribution testing. It was found that all data in the IMRT group followed a normal distribution, while the ovary left (OL) Dmax and Dmean, bladder (B) V30, bowel bag (BB) V40, and bone marrow (BM) V20 in the VMAT group, as well as the OL Dmax, rectum (R) V30, spinal cord (SC) Dmax, and B V40 in the HT group, did not follow a normal distribution. The ANOVA and Kruskal-Wallis tests were performed separately to compare the differences. The differences in ovary right (OR) Dmax, femoral head left (FHL) Dmean, B V30 and V40, BB V40, BM V20, and SC were statistically significant (F = 8.394, p = 0.001; F = 5.021, p = 0.014; H = 12.943, p = 0.002; H = 15.01, p = 0.001; H = 7.837, p = 0.020; H = 6.720, p = 0.035; H = 15.037, p = 0.001). Upon further comparison, the OR Dmax (3.10

Advancements in radiotherapy technology made the protection of normal organ function during treatment a key focus in clinical research. The protection of normal organs like the hippocampus, heart, parotid, and R during radiotherapy has been extensively studied and widely adopted in clinical practice [43, 44, 45, 46]. The ovaries are a crucial organ that determines the reproductive health and quality of life for young women. Hence, protecting ovarian function during radiotherapy is of particular significance. After analyzing relevant literature, this study discovered that technical approaches for protecting the ovaries during radiotherapy for cervical cancer have not been widely reported, highlighting a significant gap for research for this technology. Currently, the prevailing technical trends in preserving ovarian function during cervical cancer radiotherapy focus on several pivotal aspects: first, it is widely acknowledged that ovaries exhibit high radiation sensitivity. Second, a standardized tolerance dose for the ovaries remains undefined, with variations that closely correlated to patient age, radiotherapy method, and chemotherapy regimen. Third, extensive research has elucidated the safety of ovarian protection and established the maturity of techniques such as OT. Finally, modern radiation techniques, including IMRT, VMAT, and HT, have emerged as effective strategies for safeguarding ovarian function.

In this study, 77 patients with normal ovarian function prior to radiotherapy had their ovarian function assessed following radiotherapy. After excluding cases of complete ovarian function loss, 56 patients (72.7%) maintained their ovarian function after one year follow-up, achieving a satisfactory outcome. Yin et al. [25] carried out a study on ovarian protection in 105 cervical cancer patients, finding that 41 patients (39%) maintained their ovarian function after one-year follow-up. In our study, the dose limits for the ovaries in radiotherapy planning were established as Dmax

Winarto et al. [47] concluded that, when the prescribed dose for the pelvic field in traditional cervical cancer treatment was 45 Gy, the dose to the ovaries at various displacement positions, based on the calculated isodose distribution curve perpendicular to the central axis of the radiation beam, ranged from approximately 1% to 10% of the prescribed dose, or 0.45–4.5 Gy. During surgeries for cervical cancer patients, doctors are often unaware of the exact location of the radiation target area. Therefore, repositioning the ovaries to an appropriate position is a crucial factor in protecting them during radiation therapy. Some researchers have adopted deep learning techniques to predict dose distribution for cervical cancer, assisting clinicians in performing OT surgery [40]. Lv et al. [26] analyzed 176 ovaries in a pelvic cancer radiotherapy plan involving ovarian-sparing. Among them, 32 ovaries had lower margins above the PTV, while 144 had lower margins below the PTV. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was established based on the relationship between the lower margin of the ovary and the iliac crest, as well as the actual Dmax of the ovary, to predict the optimal cutoff point of Dmax

This study compared the dosimetric disparities among IMRT, VMAT, and HT techniques in ovarian-sparing radiation therapy plans for cervical cancer. The result show that the utilization of HT enables superior homogeneity in the PTV, ensuring optimal coverage of the prescribed dose to the target while effectively managing bilateral Dmax and Dmean volumes, as well as minimizing exposure to other surrounding normal tissues. IMRT offers advantages in maintaining precise control over low doses within the PTV and outperforms VMAT in various dosimetric parameters. Our findings are consistent with previous reports. Huang et al. [36] found that IMRT plans with ovarian protection successfully reduced the ovarian dose while meeting the D95% target prescription requirements, significantly reducing ovarian radiation toxicity. This results align with the findings of this study. Dong et al. [37] reported that the median dose to the ovary in coplanar and noncoplanar IMRT plans was 731 cGy and 680 cGy, respectively, with the noncoplanar design reducing the dose to the ovary. The ovarian dose in this study is higher than the reported in the aforementioned study. A literature review revealed that there are limited reports on the design of approaches for radiation therapy plan focused on ovarian protection in cervical cancer radiotherapy. This study provides the first dose comparison among IMRT, VMAT, and HT techniques, offering specific methods for plan design and serving as a reference solution for medical physicists.

OT is a key step in protecting the ovaries during cervical cancer radiotherapy. Significant advancements have been made in the surgical technique for ovarian relocation. Although ovarian dose thresholds have not been standardized, it is well established that ovarian tolerance doses are closely correlated with patient age, absorbed dose, and chemotherapy regimen. In this study, we propose an ovarian dose threshold to preserve ovarian function, with Dmax

All data generated and analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

XC and XL designed the research study. XC and LS performed the research. JL provided help and advice on the plan design for ovary-sparing cervical cancer radiotherapy. XC and LS analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Ethical review and informed consent were involved. The ethical guidelines of the Helsinki Declaration were followed, and the study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Zhejiang Cancer Hospital (IRB-2024-1283 (IIT)). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to treatment.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant NO.LGF22H160050 and Zhejiang medicine and health plan project NO.2022ZH003.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.