1 General Surgery Department, Medipol University, 34196 Istanbul, Turkey

2 Obstetric and Gynecology Department, Medipol University, 34196 Istanbul, Turkey

Abstract

Abdominal wall endometriosis, which can affect the rectus abdominis muscle, has been documented in association with cesarean section scars or along pathways formed by abdominopelvic surgeries. Our study aimed to assess the risk of developing abdominal wall endometriomas following surgical interventions (cesarean section, myomectomy) on the uterine wall.

Between 2011 and 2021, a total of 19,574 patients underwent cesarean section delivery through a Pfannenstiel incision. The average age of patients was 36 (20–58) years. On average, 1.5 to 2.0 years after cesarean section, 204 patients developed abdominal wall endometrioma (Group I). The control group (Group II) comprised 204 patients who had undergone cesarean section by the same method but did not develop scar endometriosis. During the same period, 200 patients underwent myomectomy with a similar incision for intramural and submucosal myomas (Group III). Postoperatively, these patients were also monitored for the development of endometrioma. One of the patients who underwent myomectomy also had surgery for an ectopic pregnancy at the same time. The data analysis included descriptive statistical methods, such as calculating the mean ± standard deviation, median (min–max), and frequencies (n (%)). The Shapiro-Wilk normality test, Kruskal-Wallis test, Dunn’s multiple comparison test, Chi-Square test, and Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact test were applied. The results were evaluated for statistical significance at a level of p < 0.05.

Abdominal wall endometriomas developed in 204 of 19,574 patients who delivered by cesarean section (1.04%). Endometrioma development was significantly higher in Group I, where estrogen levels were elevated (p < 0.001). The most common complaints among the patients were swelling and cyclical pain in the abdominal wall. 9 of the 204 patients who had previously developed abdominal wall endometriomas experienced recurrence (4.41%). An abdominal wall endometrioma developed in the patient who underwent myomectomy and surgery for ectopic pregnancy simultaneously (0.5%).

Endometrioma is a multifactorial condition. High estrogen levels, surgical techniques, and an increased imbalance between estrogen and progesterone levels can trigger inflammation and lead to the development of endometriomas. We suggest that further detailed studies are needed to better understand these mechanisms.

Keywords

- abdominal wall endometrioma

- section

- intramural myoma

- submucous myoma

- recurrence

Endometriosis is a medical condition in which tissue similar to the lining of the uterus, the endometrium, begins to grow outside the uterus. This can occur on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, the outer surface of the uterus, and other organs within the pelvic cavity. It can cause various symptoms such as pelvic pain, painful periods, and infertility. Endometriosis impacts around 15% to 40% of women in their childbearing years, typically occurring within the abdominal cavity, particularly in the pelvis, and sometimes in locations outside of the pelvis [1]. Previous surgical procedures, such as cesarean sections or hysterectomies, can lead to this condition. Abdominal wall endometrioma (AWE), also known as extrauterine endometriosis or scar endometriosis, is a rare condition where endometrial tissue is found in the subcutaneous fatty layer or muscles of the abdominal wall. AWE typically occurs due to the spread of endometrial tissue at the incision site during obstetrical or gynecological surgeries. This can occur as a result of previous surgical procedures, such as cesarean sections or hysterectomies, or from other abdominal surgeries [2, 3]. The incidence of scar endometriosis following a cesarean section is estimated to be around 0.03% to 1% [4, 5, 6]. The typical symptoms of this condition may involve discomfort, puffiness, and the observation of a bump or growth near the scar area. This ailment commonly affects women aged between 24 and 47 years [4].

There are 2 main theories proposed for the development of scar endometriosis: the cellular transport theory and the coelomic metaplasia theory. The cellular transport theory suggests that endometrial cells are transported to different areas of the body through various channels such as lymphatic vessels, blood vessels, or surgical procedures, where they implant and grow, leading to the development of scar endometriosis. The coelomic metaplasia theory suggests that cells resembling endometrial tissue can undergo a transformation from the lining of the abdominal cavity (coelomic epithelium) in response to hormonal or inflammatory stimuli, leading to the formation of scar endometriosis. Both theories provide explanation for the occurrence of scar endometriosis [5]. Other causes thought to be related to the development of surgical scar endometriosis include hematogenous and lymphatic spread [6]. The precise process underlying the development of scar endometriosis is not completely understood.

Especially during the postpartum period, estrogen levels can be elevated after a cesarean section. The heightened presence of estrogen can potentially affect the endometrium and promote the expansion of endometrial tissue outside the uterus. When it comes to estrogen exposure and the spread of endometrial cells, local growth factors may play a role in the growth and sustenance of these cells beyond the uterus [7, 8, 9].

The goal of this study was to determine the frequency and causes of abdominal wall endometrioma developing in the suprapubic transverse Pfannenstiel incision line and rectus abdominis muscle in 19,574 female patients who gave birth by cesarean section between 2011 and 2021 in our health institution and 200 women operated for “intramural and submucous myoma” in the same period.

The research protocol was approved by Istanbul Medipol University Ethics Committee (E-10840098-772.02-7514). The aim of this study was to determine the frequency and causes of abdominal wall endometrioma after surgical interventions such as cesarean section and myomectomy in cases where the uterine wall was opened. All procedures conducted in the study adhered to ethical principles and followed the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. This study was a single center study conducted retrospectively in 608 cases. Patients who gave birth by cesarean section with and without endometrioma and had myomectomy were included in the group. We did not include patients who had normal births in the study.

Group I; Abdominal wall endometrioma (+) cesarean section patients: 204, Group II; Cesarean section patients without abdominal wall endometrioma: 204 and, Group III; intramural & submucous myomectomy: 200 cases operated by the same general surgeon and gynecologist between 2011 and 2021. After receiving ethics committee approval for the study, symptoms of patients, laboratory tests, radiologic examinations, surgical procedure, intraoperative findings and postoperative complications, and pathology results were evaluated in terms of recurrence and recovery criteria. The inclusion of the cases in the research was to determine abdominal wall endometrioma (n = 204) and intramural + submucous myoma (n = 200) based on clinical findings and radiological imaging (superficial & transvaginal ultrasound). As some of the patients were illiterate, we obtained written consent from their relatives.

All patients underwent thorough questioning and examination in the outpatient department before being individually admitted to the hospital on the day of surgery. The preanesthetic evaluation was conducted by the same anesthesia team for each patient. After the anesthesia, and the surgical area was cleaned of hair, we used an antiseptic cleansing agent, povidone iodine in the surgical field, and 2 preoperative doses of antibiotic were used. All patients were operated on with a transverse Pfannenstiel incision in supine position.

In cases of abdominal wall endometrioma following a cesarean section, a wide excision with a 1-cm margin was performed to minimize the risk of recurrence. The fascia was sutured with 2/0 polydioxanone synthetic (PDS) loop. Out of the 204 patients who underwent surgery for abdominal wall endometrioma, 110 had the endometrioma localized above the rectus abdominis muscle fascia, while 94 had it localized at the level of the rectus abdominis muscle facia. No skin flap was needed to cover the tissue after resection or mesh to repair the fascia defect. After the surgery, the patients’ complaints decreased dramatically.

For adenomyotic lesions, the same transverse Pfannenstiel incision was used. Complete excision of intramural and submucous myomas from normal myometrium was performed. Care was taken to avoid unwanted removal of normal myometrial tissues.

During the same period, a control group consisting of 204 patients who did not develop abdominal wall endometrioma clinically and radiologically during at least 1 year of follow-up after giving birth by cesarean section was created.

Statistical analyses for this study were conducted using the NCSS (Number Cruncher Statistical System) 2007 Statistical Software package program from Utah, USA. Descriptive statistics for the variables are presented as mean

Between 2011 and 2021, 19,574 patients delivered by cesarean section. The average age of patients who underwent cesarean section was 30 (16–52) years. Abdominal wall endometrioma developed in 204 of these patients (Group I) (1.04%), on average 12–18 months after birth. During the same period, 200 patients underwent myomectomy surgery due to intramural and submucous myoma (Group III). The average age of patients who underwent myomectomy and abdominal wall endometrioma was 43.0 (31.0–58.0) years, and 31.0 (20.0–43.0) years respectively. A control group was created, including a similar number of patients who gave birth by cesarean section in the same period and did not develop abdominal wall endometrioma (Group II). We followed patients for approximately 1.5–2 years to determine the development of endometrioma after cesarean section and myomectomy surgeries. Preoperative laboratory values were compared and are shown in Table 1. In this table, we compared various laboratory parameters between the 3 different patient groups. There was a significant difference in age between the groups (p

| Variables | Group I (n = 204) | Group II (n = 204) | Group III (n = 200) | p |

| Mean | Mean | Mean | ||

| Median (Min–Max) | Median (Min–Max) | Median (Min–Max) | ||

| Age (year) | 31.53 | 33.64 | 42.49 | |

| 31.0 (20.0–43.0) | 34.0 (23.0–44.0) | 43.0 (31.0–58.0) | ||

| E2 (pg/mL) | 202.03 | 131.39 | 180.54 | |

| 188.0 (37.0–396.0) | 97.0 (30.0–398.0) | 182.5 (28.0–387.0) | ||

| Pg (ng/mL) | 2.77 | 3.33 | 5.79 | |

| 2.0 (0.10–23.0) | 1.32 (0.10–24.0) | 3.0 (0.10–32.0) | ||

| HTC (%) | 33.85 | 34.02 | 33.05 | |

| 34.0 (27.0–39.0) | 34.0 (28.0–38.0) | 33.0 (26.72–40.15) | ||

| HGB (g/dL) | 10.34 | 10.45 | 9.83 | |

| 10.0 (8.0–12.30) | 10.4 (8.5–12.0) | 10.0 (7.0–12.60) | ||

| WBC (103/mL) | 7223.06 | 7278.62 | 7100.17 | |

| 7195.0 (9.0–10,960.0) | 7320.0 (4485.0–19,885.0) | 6830.0 (4718.0–10,740.0) | ||

| PLT (103/mL) | 264.46 | 244.03 | 197.44 | |

| 260.0 (135.0–390.0) | 243.0 (174.0–372.0) | 197.0 (95.0–320.0) | ||

| APTT (sec) | 29.37 | 29.47 | 31.13 | |

| 30.0 (23.0–34.0) | 29.0 (23.0–36.0) | 32.0 (23.0–45.0) | ||

| INR | 0.93 | 0.90 | 0.91 | 0.008& |

| 0.89 (0.76–8.86) | 0.89 (0.80–1.0) | 0.91 (0.68–1.23) | ||

| SGPT (u/L) | 29.52 | 26.82 | 32.04 | |

| 34.0 (18.0–43.0) | 27.0 (11.60–42.0) | 34.0 (11.0–41.0) | ||

| Glucose (mg/dL) | 90.67 | 90.15 | 91.81 | 0.173& |

| 90.0 (70.0–125.0) | 90.0 (70.0–137.0) | 90.0 (75.0–125.0) | ||

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | 0.75 | 0.78 | 0.76 | 0.105& |

| 0.75 (0.56–1.0) | 0.77 (0.55–1.30) | 0.76 (0.45–1.20) | ||

| TSH (mIU/L) | 4.03 | 2.91 | 3.28 | |

| 4.0 (2.45–6.40) | 2.66 (0.35–6.45) | 2.98 (0.29–23.60) | ||

| Diameters (mm) | 33.51 | – | 60.51 | |

| 34.0 (19.0–43.0) | 60.0 (35.0–100.0) |

&, Kruskal-Wallis Test; #, Mann-Whitney U test; SD, standard deviation; E2, estrogen; Pg, progesterone; HTC, hematocrit; HGB, hemoglobin; WBC, white blood cell count; PLT, platelet; APTT, activated partial thromboplastin time; INR, international normalized ratio; SGPT, serum glutamate pyruvate transaminase; TSH, thyroid stimulating hormone.

The results of Dunn’s multiple comparisons Test are presented in Table 2. According to these results, the differences in ages between all comparison groups were statistically significant (p

| Groups | Age | Estrogen | Pg | HTC | HGB | PLT | APTT | INR | SGPT | TSH |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Myomectomy/Caserean with endometrıoma (Group III/Group I) | 0.072 | 0.002 | 0.950 | 0.006 | ||||||

| Myomectomy/Caserean (Group III/Group II) | 0.026 | 0.052 | ||||||||

| Caserean with endometrıoma/Caserean (Group I/Group II) | 0.463 | 0.771 | 0.423 | 0.973 | 0.714 | 0.007 |

The differences in PLT between all comparison groups were statistically significant (p

Regarding APTT values, the differences between Group III and Group I, as well as between Group III and Group II, were statistically significant (p

Regarding INR values, the difference between Group III and Group I was not statistically significant (p = 0.950). The difference between Group III and Group II was statistically significant (p = 0.026). The difference between Group I and Group II was not statistically significant (p = 0.714). For SGPT values, the difference between Group III and Group I was statistically significant (p = 0.006). The difference between Group III and Group II was statistically significant (p

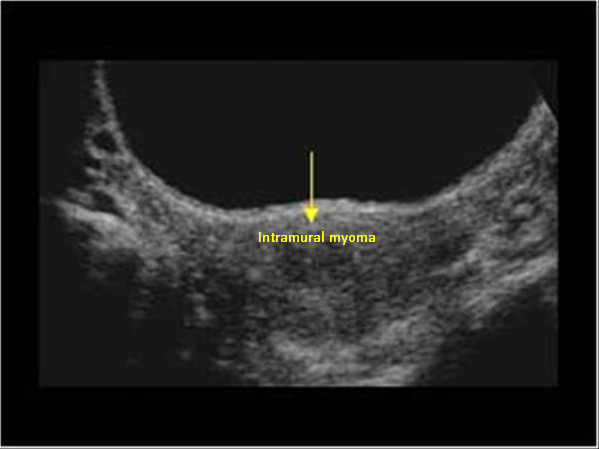

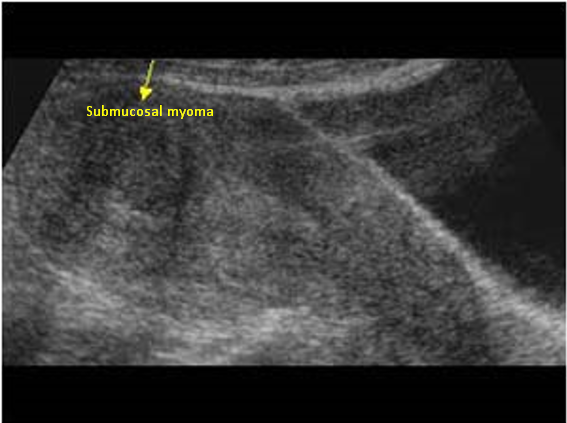

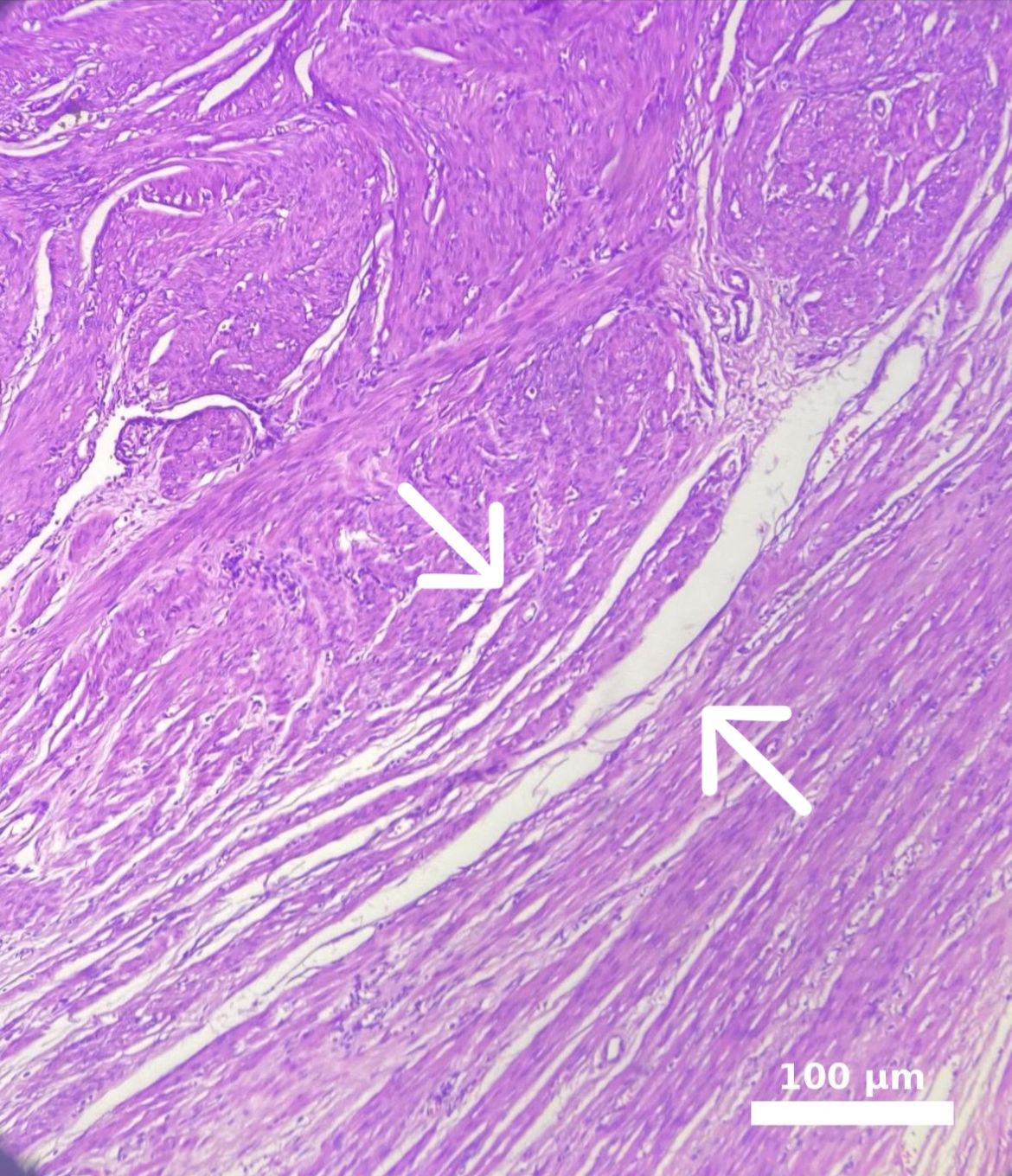

Myoma patients presented to the gynecology clinic due to complaints of prolonged menstrual bleeding and dysmenorrhea. During the transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) examination, an intramural myoma was detected in 105 patients, submucous myoma in 35 patients, and intramural and submucous myoma detected in 60 patients (Figs. 1,2). Ovarian endometriosis was present in 105 of these patients. These patients were operated on by gynecologists. Pathology results were compatible with leiomyoma uteri (Fig. 3). The hospital stay was for 2 days. In the postoperative period, surgical site infection developed in 6 patients and hematoma at the incision line in 3 patients. Hematoma drainage was performed in only 1 patient. Surgical site infection resolved with antibiotic treatment. During the follow-up period, abdominal wall endometrioma developed only in the patient who underwent intervention due to myomectomy + ectopic pregnancy at the same time (0.5%). Characteristics of the 3 groups are shown in Tables 3,4.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Transvaginal ultrasonography of intramural myoma.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Transvaginal ultrasonography of submucous myoma.

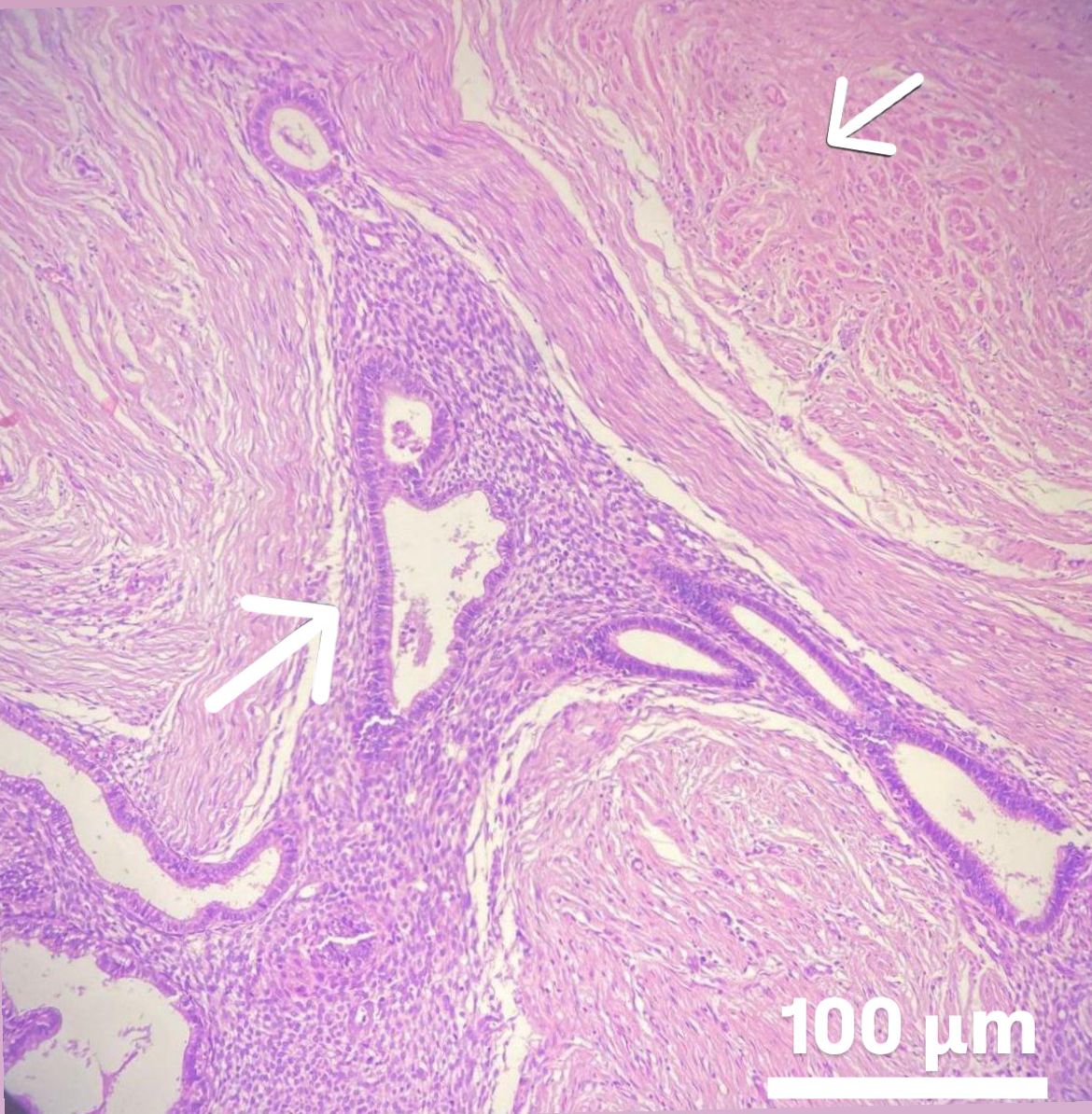

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Microscopic appearance of intramural myoma. The white line marked with a white arrow in the image delineates the border between the leiomyoma and the adjacent myometrium. Endometrioma tissue is visible on the left side. The myometrium in the lower right corner appears distorted due to pressure, while an intramural myoma is observed in the upper left corner. Scale bar: 100 μm (H&E, hematoxylin and eosin,

| Group I (n = 204) | Group II (n = 204) | Group III (n = 200) | p | ||

| Pain | |||||

| Yes (cyclic/non-cyclic) | 202 (182/20) (99.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 174 (87.0%) | ||

| No | 2 (1.0%) | 204 (100.0%) | 26 (13.0%) | ||

| Bleeding | |||||

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 120 (60.0%) | ||

| No | 204 (100.0%) | 204 (100.0%) | 80 (40.0%) | ||

| Mass in the abdominal/uterine wall | |||||

| Abdominal wall | 204 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | ||

| Uterine wall | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 199 (99.5%) | ||

| Frequent urination | |||||

| Yes | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 16 (8.0%) | ||

| No | 204 (100.0%) | 204 (100.0%) | 184 (92.0%) | ||

| Radiologic examination (Ultrasound-US) | |||||

| Superficial US | 204 (100.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Superficial implant | 110 (53.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Intermediate implant | 94 (46.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Transvaginal US | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 200 (100.0%) | ||

| Intramural | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 105 (52.5%) | ||

| Submucous | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 35 (17.5%) | ||

| Intramural + submucous | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 60 (30.0%) | ||

| Intraabdominal endometriosis | |||||

| Yes | 11 (5.4%) | 16 (7.8%) | 28 (14.0%) | 0.008& | |

| No | 193 (94.6%) | 188 (92.2%) | 172 (86.0%) | ||

| Location | |||||

| Posterior | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 168 (84.0%) | ||

| Other | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 32 (16.0%) | ||

| Right | 160 (78.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Left | 44 (21.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Pathology | |||||

| Leiomyoma uteri | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 199 (99.5%) | ||

| Endometriosis | 203 (99.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | ||

| Others (desmoid tumor) | 1 (0.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| Complication | |||||

| Yes | 1 (0.5%) | 6 (2.9%) | 9 (4.5%) | 0.040& | |

| No | 203 (99.5%) | 198 (97.1%) | 191 (95.5%) | ||

| Recurrence | |||||

| Yes | 9 (4.4%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | ||

| No | 195 (95.6%) | 204 (100.0%) | 200 (100.0%) | ||

&, Pearson Chi-Square test; #, Fisher-Freeman-Halton Exact Test.

| Group I (n = 204) | Group II (n = 204) | Group III (n = 200) | ||

| YES | ||||

| Appendectomy | 11 (5.39%) | 10 (4.90%) | 7 (3.50%) | |

| Caserean | 29 (14.21%) | 35 (17.1%) | 6 (3.0%) | |

| Cholecystectomy | 4 (1.96%) | 3 (1.47%) | 2 (1.0%) | |

| Cystocele | 3 (1.47%) | 1 (0.49%) | 2 (1.0%) | |

| Rectocele | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.49%) | 3 (1.5%) | |

| Hemorrhoidectomy | 7 (3.43%) | 9 (4.41%) | 3 (1.5%) | |

| Thyroidectomy | 2 (0.98%) | 2 (0.98%) | 3 (1.5%) | |

| Inguinal hernia | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 5 (2.5%) | |

| Ovarian abscess | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Ovarian cyst rupture | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.49%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| Peptic ulcus perforation | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (0.5%) | |

| NO | 148 (72.5%) | 142 (69.6%) | 166 (83.0%) | |

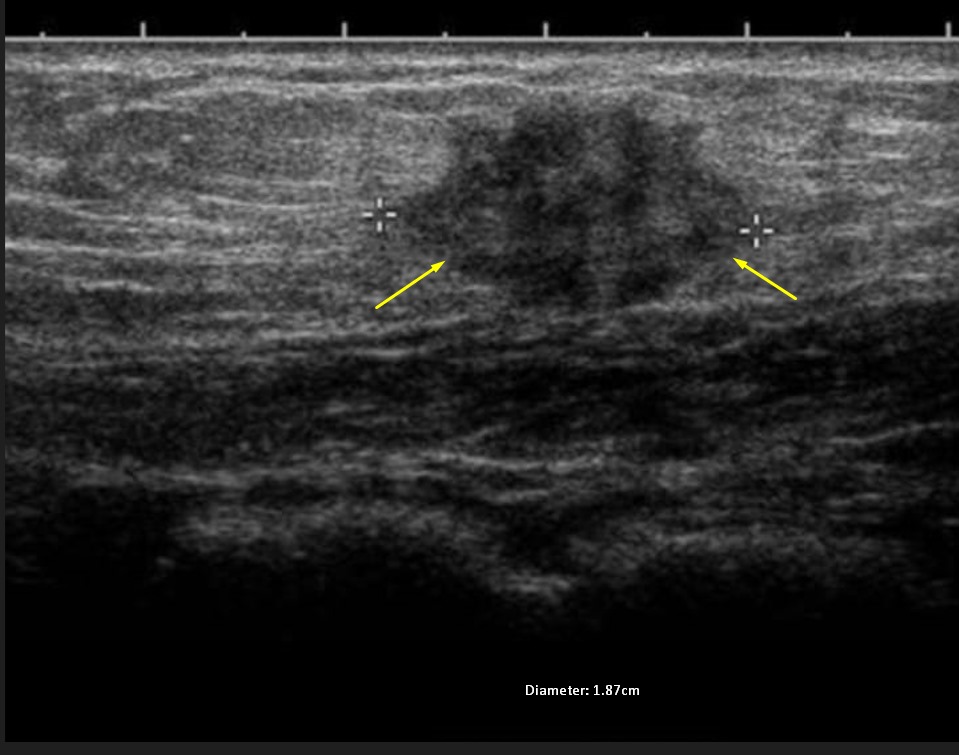

Abdominal wall endometrioma was detected in the physical and radiological examination (superficial ultrasound) (Fig. 4) of 204 patients who presented to our general surgery clinic due to complaints of swelling and pain in the abdominal wall. Masses were on the right side of the incision line in 160 (78.4%) patients. In the superficial ultrasound of the patients, AWE was above the rectus fascia in 110 patients and at the level of the rectus abdominis fascia in 94 patients. In only 1 patient, the mass was localized outside the cesarean scar site. Wide excision was performed under general anesthesia in 204 patients. The pathology of 203 patients was evaluated as compatible with endometrioma (Fig. 5). The pathology result of the remaining 1 patient was compatible with desmoid tumor. Postoperatively, only 1 patient had a hematoma. She recovered with conservative treatment. Repeat pregnancy was planned in 204 patients after an average of 2.5 years. AWE recurred in 9 of the patients in Group I during the follow-up period (4.4%). These patients underwent repeat total excision.

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. Superficial ultrasonography of abdominal wall endometrioma.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. Microscopic appearance of abdominal wall endometrioma. Arrows indicate ectopic endometrial tissue with preserved gland and stroma integrity within striated muscle and connective tissue. The rectus muscle is located in the upper right corner, while the abdominal wall endometrioma is visible in the lower left corner. Scale bar: 100 μm (H&E, hemtoxylin and eosin,

Abdominal wall endometrioma did not develop during the follow-up period in our 204 patients (Group II) who gave birth via cesarean section, although 16 of them had ovarian and peritoneal endometriosis. No pathological findings were found in the subsequent follow-up of our patients in this group, who had an average of 3 births.

Table 3: while 174 (87.0%) of the patients in Group III had pain in the preoperative period, this rate was 202 (99.0%) in patients who developed endometrioma after cesarean section (p

Table 4 shows the past surgical operations of the patients for the 3 groups. No previous surgical interventions related to endometriosis were detected in any of the groups.

Endometriosis is a gynecological disease marked by the presence of endometrial tissue outside the uterus. This growth can be categorized based on location as either pelvic, involving the uterosacral ligaments, ovaries, fallopian tubes, and pouch of Douglas, or extra pelvic, affecting areas such as surgical scars, groin, diaphragm, kidneys, liver, lungs, and pleura [10, 11]. Sometimes endometrial tissue starts to grow on the skin [12]. There are 2 main types of cutaneous endometriosis: Primary (spontaneous) cutaneous endometriosis occurs when endometrial tissue implants into the skin without any prior surgery or trauma in that area. Its etiology is not clear [13]. Secondary (scar) cutaneous endometriosis occurs when endometrial tissue is inadvertently implanted into the skin during a surgical procedure, such as a cesarean section or episiotomy [12, 13]. The most common symptoms of both types are cyclic pain, swelling, and the formation of nodules or lumps in the skin. Scar endometriosis occurs most commonly after cesarean section, at the corners of the Pfannenstiel incision line [14]. In their study, Ping Zhang et al. [14] found Pfannenstiel incision in 80% of their patients presenting with cesarean scar endometriosis. In our study, scar endometriosis was in the Pfannenstiel incision line in 203 patients. It was localized outside the incision line in only 1 patient. The mean age of affected women varied from 20–43 years with an average of 31.0 years [4].

The prevalence of endometriosis worldwide is estimated to be between 10% and 15% [15]. Structural differences of endometrioma cells arise from abnormalities in their location.

If endometrial cells settle outside the uterus, there is the potential for them to lose their normal functions. These cells normally grow and shed in a cyclical manner within the uterus. However, if they are located outside the uterus, this cyclical change may be disrupted and lead to abnormal tissue growth. Factors affecting the development of endometriosis include conditions such as genetic predisposition, immune system disorders, hormonal imbalances (especially estrogen hormone), inflammation and infections developing in the incision line [16]. Patients with endometriosis may have alterations in iron metabolism (serum iron level, ferritin, transferrin saturation, total iron binding capacity) due to chronic inflammation and menstrual blood loss [17]. Monitoring these markers of iron metabolism can help healthcare providers assess iron status and make appropriate recommendations for supplementation or treatment in patients with endometriosis. These factors lead to the formation of a pro-inflammatory environment that supports the continued presence of endometriosis, which is closely associated with the two primary symptoms of the disease: pain and infertility. So far, no specific marker for endometriosis has been detected in peripheral blood or endometrium [18]. The markers used were analyzed together with the patient’s clinical and radiological findings. Intra-abdominal endometriosis was present in 5.4% of our patients who developed scar endometriosis (Group I), 7.8% of our patients who did not develop scar endometriosis (Group II), and 14% of our patients who underwent surgery for myoma (Group III). There was no significant difference in the peripheral blood picture of all 3 groups. Rather than specific markers, the clinical and radiological findings of the patients were more significant during diagnosis.

The development of endometrioma in the abdominal wall can often be under the influence of estrogen as in our study. Group I has the highest average estrogen level 188.0 (37.0–396.0) pg/mL (p

Due to the recent increase in cesarean deliveries, it has been determined that there is an increase in the prevalence of abdominal wall endometriomas. It has been shown that the indication for cesarean section and surgical technique are not factors contributing to the development of endometriomas, as they are not seen after every cesarean section, although the risk of implantation is equal [4]. Our study also supports this situation. Only 204 of our 19,574 cesarean section patients developed scar endometriosis. Therefore, other factors such as genetics, endocrine factors, or wound environment may be contributory. Therefore, the factors determining the spread of endometrial cells and the formation of an endometrioma may differ among patients.

The incidence of abdominal wall endometrioma after cesarean section is very rare (0.03–1%) [19]. In our study it was 1.04%. Surgical technique, handling of tissue, the method of closing incisions, as well as the materials and sutures used, might affect implantation risk. Patient demographics: some populations may have genetic predispositions that increase the likelihood of endometriosis, including abdominal wall endometriomas, due to differences in hormonal receptor sensitivity or immune responses [20]. Variability in menstrual cycle characteristics, such as shorter cycles or heavier flows, could contribute to increased incidences due to more aggressive endometrial growth and potential seeding during surgical interventions [20]. Abdominal wall endometriomas and intra-abdominal endometriomas are not usually seen together. However, in rare cases, both types of endometriomas can be found in the same person. The probability of this situation occurring is very low. In our study, 11 patients in Group I had scar endometriosis and intra-abdominal endometriosis at the same time (5.4%).

However, there is no clear explanation as to exactly why endometrioma occurs, and it is thought that it may be under the influence of many factors. In a study by Ozel et al. [19], it was recommended that specific cesarean delivery practices, including effective bleeding control, thorough washing of the abdominal cavity prior to closure, and minimizing subcutaneous dead space by carefully bringing together wound edges, could potentially diminish the occurrence of AWE. The average duration between the initial surgery and the onset of AWE symptoms was found to be 14.1 months (range 1 to 72 months). In our study, AWE developed on average within 12–18 months after cesarean section.

Abdominal wall endometriosis typically presents with a noticeable lump under the skin near a previous surgical scar, accompanied by increased pain and swelling during menstruation. This condition is commonly characterized by menstrual pain, especially in individuals who have undergone cesarean section. If a palpable mass is found in the area of a surgical scar in conjunction with a history of cesarean section and menstrual pain, the diagnosis of abdominal wall endometriosis should be strongly considered [8]. Ping Zhang and colleagues [14] found that the most common reason for admission of their patients was an abdominal mass (98.5%) and accompanying cyclic pain in 87%. In our study, pain was cyclic in 182 of our patients (89.2%). Twenty of our patients described pain only with touch. Two patients with a scar endometriosis diameter of

Ultrasonography is the first-line diagnostic imaging method in the evaluation of abdominal wall abnormalities [21]. Three positions for abdominal wall endometrioma (AWE) have been identified based on its location relative to the rectus abdominis muscle: superficial placement (above the fascia of the rectus muscle), intermediate placement (at the level of the fascia of the rectus muscle), and deep placement (below the fascia of the rectus muscle) [22]. In our study, AWE localized under the muscle was not detected. On ultrasound, AWE appears as a heterogeneous hypoechoic mass with hemorrhagic and fibrous components present.

Fine needle aspiration (FNA) cytology was deemed unnecessary due to clear clinical and radiological imaging findings, along with the history of previous cesarean section, making the diagnosis of abdominal wall endometriosis well-documented. Confirmation of the diagnosis was achieved through histopathological examination of the surgical specimen. In 203 of our patients, the pathology result was consistent with endometriosis. Desmoid tumor was detected in only 1 patient. The standard treatment method is wide surgical excision [23]. Pharmacological treatment is palliative, and not effective in treating the disease completely.

Ping Zhang et al. [14], Rohit Nepali et al. [24], and Fatimah Alnafisah et al. [25], similarly managed their cases by performing surgical excision of the mass. The reported risk of recurrence following surgery ranges from 5–9% [23]. Consequently, during the excision of the mass, it is essential to ensure at least 1 cm of surrounding tissue is removed to reduce the likelihood of recurrence [26]. Recurrence was detected in 9 of our 204 patients with AWE after the next caesarean section (4.41%). We re-operated on these patients with clean surgical margins. In our patients, the AWE diameter was between 1.87 and 4.3 cm. During operation, mesh placement was not deemed necessary to repair the fascial defect. We did not have any patients who developed a hernia.

The malignancy risk of endometriosis in any region is 1%. Malignant transformations of atypical well-differentiated endometriosis are indeed rare, with clear cell carcinoma and adenocarcinomas being documented in the literature [27, 28]. No cases of cancer were identified in our study. In cases where malignancy does occur, around 80% of them are associated with endometriosis in the ovary, while the remaining 20% are found in extra-gonadal sites, such as the abdominal wall [28].

Another reason for intervention in the uterine wall is the benign masses of the uterine wall called adenomyosis. Adenomyosis is the cause of 20–30% of hysterectomy surgery. Adenomyosis can arise directly from the extension of the basal layer of the endometrium into the myometrium. Adenomyosis occurs when the endometrial glands extend into the myometrium, resulting in an ectopic location due to disruptions in the tissue barrier between the endometrial basal layer and the myometrium [29].

Ectopic localization can manifest as diffuse (adenomyosis) or focal (adenomyoma), impacting various areas of the uterus, with the posterior uterine wall frequently affected [29]. This occurrence may follow surgical curettage or placental invasion, potentially leading to additional disruptions and invasion of the endometrium. It is recognized as a type of endometriosis variant, with both conditions co-occurring in around 20% of individuals affected [16]. The most common symptoms of the disease are uterine tenderness and enlargement, dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia and dyspareunia. In 168 of our 200 patients who underwent myomectomy, the myoma was localized on the posterior wall. The incidence of the disease is higher in multiparous women as in our study [16].

In recent years, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasound have emerged as the preferred imaging techniques for diagnosing adenomyosis. Transvaginal ultrasonography (TVUS) is particularly favored in gynecological examinations because it enables a dynamic assessment of organ mobility and position. Through both two-dimensional (2D) and two-dimensional (3D) configurations, as well as color flow Doppler technology, TVUS provides a detailed view of the uterus and any associated pathologies [16]. Additionally, it is more accessible and cost-effective compared to MRI.

In transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS), adenomyosis may present as heterogeneous myometrium, cysts within the myometrium, linear patterns within the myometrium, areas with indistinct borders, unclear connection between the endometrium and myometrium, and thickening of the myometrium [30, 31]. Various studies have reported sensitivity and specificity values for TVUS in diagnosing adenomyosis ranging from 87.1% to 57.4% and 97.5% to 60.1%, respectively [16].

Adenomyosis can be treated with uterus-sparing excisional techniques, which include complete excision of adenomyosis, known as adenomyomectomy, for cases of focal adenomyosis (adenomyoma), and partial excision or cytoreductive surgery for more extensive cases, referred to as diffuse adenomyosis.

During surgery of adenomyotic lesions, they should be carefully separated from the normal myometrium tissue to avoid damaging the normal myometrial tissues. There was no widespread adenomyosis in our patients. Therefore, only total excision of myomas was performed through transverse Pfannenstiel incision.

Endometriosis is a complex and often debilitating condition that affects a significant number of individuals worldwide, causing pain, infertility, and various quality-of-life issues. Despite significant research efforts, there remain significant gaps in our understanding of its etiology, progression, and treatment outcomes. Although patients in Groups I and II (control group) underwent caesarean section, abdominal wall endometrioma developed in all patients in Group I, but it was not detected in Group II. In Group III, where myomectomy was performed, abdominal wall endometriomas developed only in a patient with an ectopic pregnancy.

It should be considered that conditions such as endometriosis and endometrioma are multifactorial and that iatrogenic factors may play a role. During menstruation, endometrial cells migrate backwards from the fallopian tubes and leak into the pelvic cavity where they implant. Genetic factors, especially the growth of these tissues secondary to excessive production of hormones such as estrogen, immune system disorders allowing endometrial tissue to survive and grow outside the uterus, and incorrect surgical techniques are important to understand the cause and effect relationship. In our patients’ hematological tests, some valuessuch as E2 and PLT count are high, as well as an increase in insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF-1) and a decrease in Caspase 3, supporting endometrioma formation. We are continuing our prospective study to determine the effect of IGF-1 on endometrioma formation.

More detailed prospective studies are needed to understand the pathophysiology of the disease and to identify risk factors. Prospective studies are vital to assessing the long-term effectiveness and safety of current and new treatments. These studies can help determine which treatments work best for specific patient groups, leading to more personalized and effective care. The main limitation of our study was that it was retrospective in nature and our resources were limited.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

NS: conception, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, writing original draft in English, re-writing after review and final edition, operations on patients, and obtaining Ethics Committee approval. SA: operations on patients, data curation, interpretation of data and review. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final version of manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. Approval of the present study was obtained from the institutional review board of University of Medipol, Medical Faculty (29.11.2023/E-10840098-772.02-7514). As some of the patients were illiterate, we obtained written consent from their relatives with the permission of the Ethics Review Board. Thus, all subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study.

We would like to express our gratitude to the referees for their suggestions and contributions. We would also like to thank Prof. Dr. Ozkan GORGULU, Head of the Department of Biostatistics at Kırsehir Ahi Evran University, who made the statistical calculations in this study.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.