1 Department of Clinical Medical, Guizhou Medical University, 550004 Guiyang, Guizhou, China

2 School of Basic Medical Sciences, Capital Medical University, 100015 Beijing, China

3 Department of Gynecological, The Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, 550001 Guiyang, Guizhou, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Perimenopausal women often require hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which is associated with an increased risk of developing breast nodules compared to women in other age groups. Consequently, this study aimed to identify risk factors for breast nodule development in perimenopausal women and to develop a predictive model to mitigate these risks.

This prospective cohort study included 436 perimenopausal women who underwent breast ultrasound examinations at the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, China. Clinical data were collected, with 304 cases (70%) assigned to the modeling group, while the remaining 132 cases (30%) were allocated to the validation group using a computerized randomization method. Subsequently, participants in each group were categorized into either the control group or the disease group based on the presence or absence of breast nodules. Risk factors associated with the occurrence of breast nodules in perimenopausal women from the modeling group were analyzed using univariate analysis and multivariate logistic regression. A nomogram predictive model was subsequently constructed using R software. The predictive accuracy and discriminative ability of the model for perimenopausal breast nodules were evaluated in both the modeling and validation groups using goodness-of-fit curves and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis.

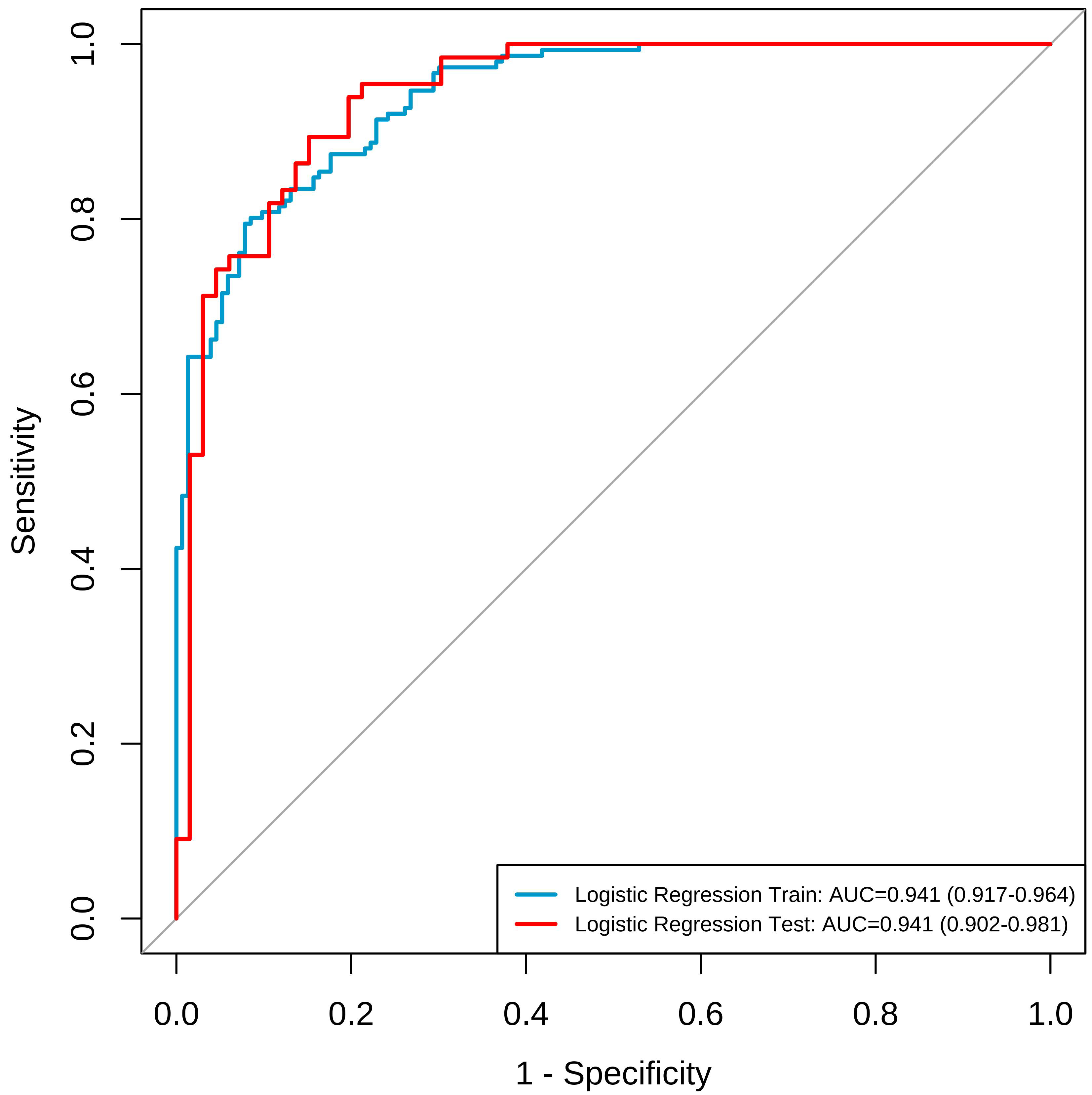

Factors exhibiting significant differences in the univariate analysis were included in the multivariate logistic regression model. The results revealed that family relationships, the modified Kupperman score, depression, dietary status, estradiol (E2), triglycerides (TG), and total cholesterol (TC) were independent risk factors for the development of breast nodules during perimenopause. In contrast, elevated high follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) levels were identified as a protective factor against perimenopausal breast nodules. A nomogram predictive model was developed to assess the predictive validity of breast nodules occurrence during perimenopause, using goodness-of-fit curves. The results showed χ2 = 4.936, p = 0.764 for the training group, and χ2 = 8.642, p = 0.071 for the testing group. The model’s discrimination was evaluated by the ROC curve, with the results showing an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.941 for the training model, along with a specificity of 91.7%, and sensitivity of 96.4%. In the testing model, the AUC was also 0.941, with a sensitivity of 90.2% and specificity of 98.4%.

Poor family relationships, unhealthy dietary habits, severe menopausal symptoms, severe depression, elevated estrogen levels, and elevated blood lipid levels were identified as independent risk factors for the development of breast nodules during perimenopause. In contrast, high FSH levels serve as a protective factor against perimenopausal breast nodules. The predictive model developed using this approach demonstrates strong predictive accuracy and discriminative power.

Keywords

- perimenopause

- breast nodules

- risk factors

- nomogram prediction model

Breast nodules, detectable through breast ultrasound, encompass a range of lesions, including cysts, solid or mixed masses, intraductal masses, and space-occupying lesions. These represent the most common types of breast diseases. Recent advancements in ultrasound technology have significantly improved the detection rate of breast nodules, with study suggesting that approximately 20% to 30% of these nodules may eventually progress to cancer [1]. Breast cancer remains the most prevalent malignant tumor in women worldwide, with particularly high morbidity and mortality rates, especially in low- and middle-income countries, where the incidence can reach as high as 62.1% [2]. Epidemiological surveys indicate that the prevalence of breast disease among Chinese women is 30% [3], although the exact pathogenesis remains under investigation. During perimenopause, a decrease in estradiol (E2) levels reduces the negative feedback regulation of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), leading to elevated levels of FSH and LH. Substantial evidence links E2, FSH, and LH to the formation of breast nodules [4]. Hormone supplementation therapy (HRT), which addresses many issues experienced by perimenopausal women, may have an impact on mammary gland health during its use. The incidence of breast nodules among perimenopausal women is rising, influenced by changing social roles and increased stress. However, the factors influencing the development of this condition remain uncertain. Therefore, an in-depth study of these factors is essential to develop timely and targeted interventions that can significantly improve patient outcomes. In perimenopausal women, the decline in ovarian function, fluctuating estrogen levels, and other endocrine changes significantly impact the growth and development of breast tissue, thereby elevating the risk of breast nodule formation [5]. Research indicates that excessive secretion of E2 and prolactin, or insufficient secretion of androgens and progesterone (P), can overstimulate mammary tissue, potentially leading to breast nodules [6]. A meta-analysis suggests that estrogen may increase the risk of breast nodules in perimenopausal women [7]. Additionally, study indicate that the increased incidence of breast nodules in this population may be associated with heightened estrone levels [8].

Depression, increasingly recognized as a global public health concern, is a contributing factor to the development of breast nodules and is more prevalent during the hormonally dynamic phase of perimenopause [9]. Cross-sectional study has highlighted the increased susceptibility of perimenopausal women to depression, irritability, and other adverse mental and psychological conditions [2]. Traditional Chinese medicine suggests a strong link between emotional factors and the incidence of breast diseases [10]. Nevertheless, the specific influence of depression during perimenopause on the development of breast nodules requires further investigation.

Perimenopause is characterized by a range of changes, including hot flashes, night sweats, insomnia, memory loss, and reduced concentration, collectively referred to as perimenopausal syndrome. The modified Kupperman score, a widely recognized self-assessment scale, quantifies the severity of these symptoms. However, the relationship between the severity of perimenopausal syndrome and the development of breast nodules remains a topic of ongoing debate [11, 12].

This study aims to enhance understanding of breast nodules in perimenopausal women by collecting comprehensive data and employing statistical analyses to identify factors significantly associated with an increased risk of developing breast nodules. It seeks to provide evidence-based screening and preventive measures to improve breast health in this demographic. Furthermore, the findings of this study will be instrumental in optimizing breast health counseling and intervention strategies, ultimately reducing the risk of breast nodules and associated conditions in perimenopausal women.

From January 2022 to January 2024, this prospective cohort study enrolled a total of 436 perimenopausal women who underwent breast ultrasound examinations at the menopausal clinic of the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University. Inclusion criteria: ① Perimenopausal women in the early menopausal transition period (–2 stage) to the early postmenopausal period (+1a stage), as defined by the Stages of Reproductive Aging Workshop +10 (STRAW+10). Early menopausal transition (–2 stage) is characterized by increased menstrual cycle length variability, defined as a persistent change of 7 days or more between consecutive cycle lengths. Persistence is defined as recurrence of this variability within 10 cycles following the initial occurrence. Late menopausal transition (–1 stage) is marked by intervals of amenorrhea lasting 60 days or more. The +1a stage, representing the early postmenopausal period, begins 1 year after the final menstrual period (FMP), and corresponds to the end of perimenopause [13]. ② Women who developed new breast nodules during the perimenopause period. ③ All patients were informed about the study and provided written informed consent. Exclusion criteria: ① Patients with severe endocrine diseases, such as diabetes mellitus or thyroid disease. ② Patients with abnormal cardiac, hepatic, or renal functions. ③ Patients with cognitive or neurological impairments. ④ Patients with other malignant tumors. ⑤ Patients who were lost to follow-up. ⑥ Patients who had previously undergone hormone therapy. ⑦ Women with previous breast nodules. This study adhered to the ethical guidelines and was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, People’s Republic of China (Approval Number: 2022no.251). It was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

The study collected the following data from each participant’s basic questionnaire: demographic information (age, ethnicity, education level, monthly income, employment status), lifestyle habits (alcohol consumption history, diet), family relationships, and anthropometric measurements (height, weight, body mass index (BMI)). The participants’ depressive status was evaluated using the validated Chinese version of the Self-Assessment Depression Scale (SDS). The SDS, a self-report tool, evaluates the symptoms and severity of depression in outpatient settings. Depression severity was classified using SDS scores as follows: 53–62 for mild depression, 63–72 for moderate depression, and

Following the questionnaire, participants underwent breast ultrasound examinations conducted by experienced ultrasound specialists. Breast nodules, including cysts, solid or mixed masses, intraductal masses, and space-occupying lesions, were identified. Participants with ultrasound findings suggestive of breast nodules were categorized into the case group, while those without such findings were placed in the control group. Blood samples (5 mL) were collected from the antecubital vein after an 8-hour fast to measure LH, P, FSH, testosterone (T), prolactin (PRL), E2, triglyceride (TG), and total cholesterol (TC). The samples were analyzed in the laboratory of the Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University.

In this study, R4.1.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) and SPSS 26.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) were utilized for data organization and statistical analysis. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of the data. Measurement data that followed a normal distribution were expressed as mean

Among the perimenopausal women included in the analysis, 151 were found to have breast nodules, while 153 did not. No statistically significant differences (p

| Variables | Type | The case group (151) | The control group (153) | Z/χ2 | p |

| Ethnicity (%) | Han nationality | 117 (77.48) | 116 (75.82) | χ2 = 0.118 | 0.731 |

| Other | 34 (22.52) | 37 (24.18) | |||

| Education (%) | Junior high and below | 29 (19.21) | 23 (15.03) | Z = 0.317 | 0.751 |

| High school/secondary | 11 (7.28) | 23 (15.03) | |||

| University/college | 67 (44.37) | 65 (42.48) | |||

| Masters/doctorate | 44 (29.14) | 42 (27.45) | |||

| Monthly income (%) | 66 (43.71) | 82 (53.60) | Z = 1.381 | 0.167 | |

| 0.5–1 million | 74 (49.01) | 60 (39.22) | |||

| 1–2 million | 11 (7.28) | 11 (7.19) | |||

| Employment status (%) | Officer | 63 (41.72) | 49 (32.03) | Z = –1.597 | 0.110 |

| Company work | 33 (21.85) | 42 (27.45) | |||

| Freelancer | 37 (24.50) | 35 (22.88) | |||

| Housewife | 18 (11.92) | 27 (17.65) | |||

| Family relationships (%)* | Harmony | 97 (64.24) | 119 (77.78) | Z = 2.726 | 0.006 |

| Ordinary | 44 (29.14) | 31 (20.26) | |||

| Poor | 10 (6.62) | 3 (1.96) | |||

| Alcohol consumption history (%) | No | 134 (88.74) | 141 (92.16) | χ2 = 1.027 | 0.311 |

| Yes | 17 (11.26) | 12 (7.84) | |||

| Diet (%) | Light | 37 (24.50) | 68 (44.44) | Z = 3.818 | 0.001 |

| Moderate | 72 (47.68) | 61 (39.87) | |||

| Highly palatable | 42 (27.81) | 24 (15.69) | |||

| Age [M (Q1, Q3)] | 49.00 (47.00, 52.00) | 50.00 (47.00, 53.00) | Z = –2.197 | 0.028 | |

| Height [M (Q1, Q3)] | 158.00 (155.00, 160.00) | 157.00 (154.00, 160.00) | Z = 0.886 | 0.376 | |

| Weight [M (Q1, Q3)] | 55.00 (52.00, 60.00) | 55.00 (50.00, 60.00) | Z = 0.984 | 0.325 | |

| BMI [M (Q1, Q3)] | 22.38 (20.70, 24.44) | 22.06 (20.58, 24.14) | Z = 0.660 | 0.509 |

Note: p-values

BMI, body mass index; M (Q1, Q3), median and interquartile range.

The results of Spearman’s correlation analysis of demographic characteristics (Table 2) indicated that ethnicity, education level, monthly income, employment status, height, weight, and BMI were not significantly associated with the occurrence of breast nodules (p

| Variables | r | p |

| Ethnicity (%) | –0.020 | 0.735 |

| Education (%) | 0.018 | 0.752 |

| Monthly income (%) | 0.079 | 0.168 |

| Employment status (%) | –0.092 | 0.111 |

| Family relationships (%) | 0.157 | 0.006 |

| Alcohol consumption history (%) | 0.058 | 0.312 |

| Diet (%) | 0.219 | |

| Age (median [IQR]) | –0.126 | 0.028 |

| Height (median [IQR]) | 0.051 | 0.377 |

| Weight (median [IQR]) | 0.057 | 0.326 |

| BMI (median [IQR]) | 0.038 | 0.510 |

Note: p-values

BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range.

As demonstrated in Table 3, the modified Kupperman score was significantly associated with the occurrence of breast nodule (p

| Variables | Degree | The case group (151) | The control group (153) | Z | p |

| With modified Kupperman score (%) | Normal | 11 (7.28) | 48 (31.37) | Z = 6.144 | 0.001 |

| Mildly | 46 (30.46) | 51 (33.33) | |||

| Moderate | 59 (39.07) | 46 (30.07) | |||

| Severe | 35 (23.18) | 8 (5.23) | |||

| Depression (%) | Normal | 40 (26.49) | 100 (65.36) | Z = 7.281 | 0.001 |

| Mildly | 39 (25.83) | 29 (18.95) | |||

| Moderate | 46 (30.46) | 20 (13.07) | |||

| Severe | 26 (17.22) | 4 (2.61) |

Note: p-values

Spearman’s correlation analysis, as presented in Table 4, indicated a significant positive correlation (p

| Variables | r | p |

| With modified Kupperman score (%) | 0.353 | 0.001 |

| Depression (%) | 0.418 | 0.001 |

Note: p-values

As presented in Table 3, depression was significantly associated with the development of breast nodules (p

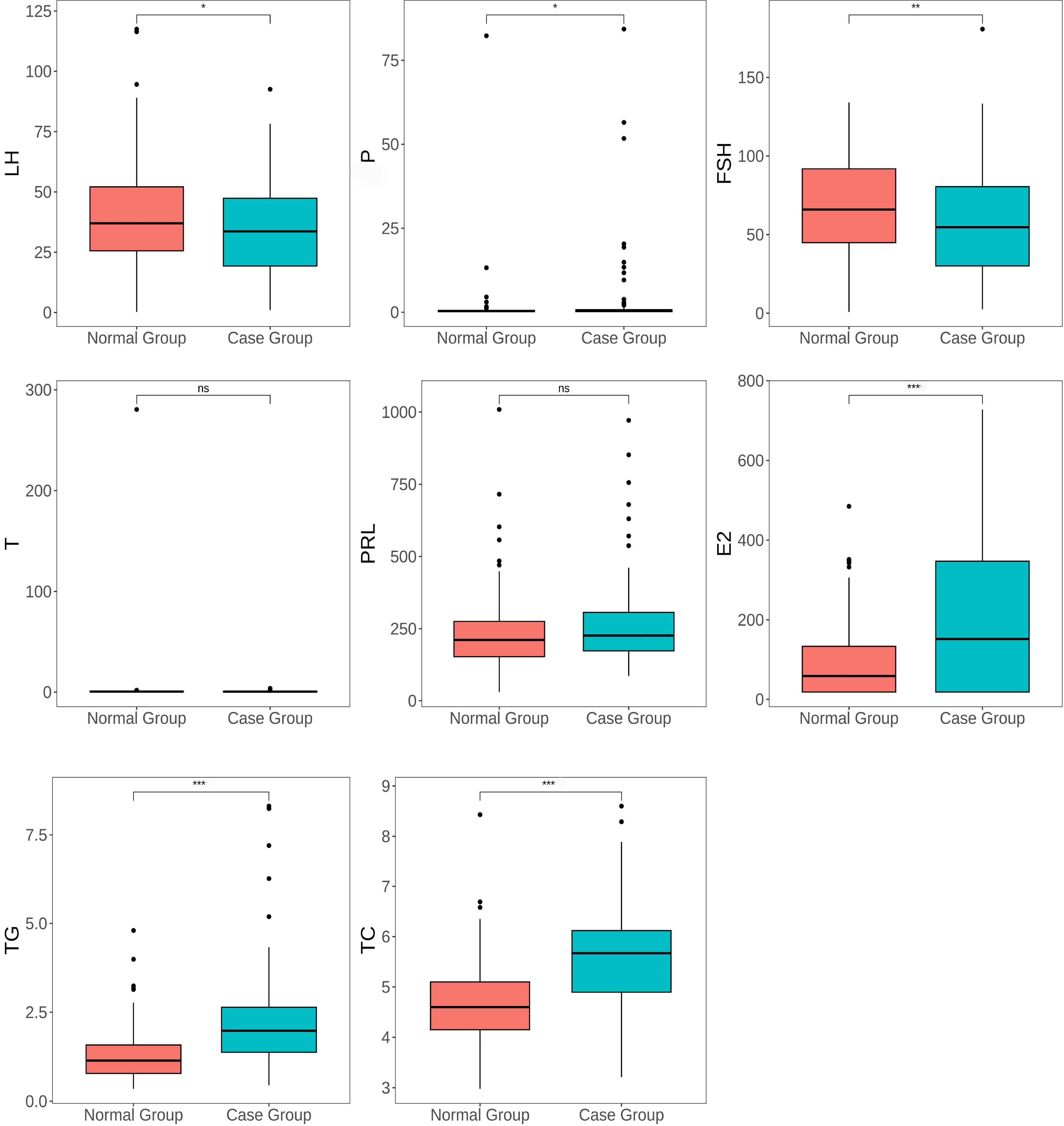

As observed in Table 5, the levels of LH (p = 0.039), P (p = 0.028), FSH (p = 0.001), E2 (p = 0.001), TG (p = 0.001), and TC (p = 0.001) showed significant differences between the control group and the case group. In contrast, the level of T (p = 0.679) and PRL (p = 0.078) did not demonstrate significant differences between the two groups (p

| Variables | The case group (151) | The control group (153) | Z | p |

| LH, M (Q1, Q3) | 33.65 (19.30, 47.37) | 37.01 (25.58, 52.10) | Z = –2.059 | 0.039 |

| P, M (Q1, Q3) | 0.47 (0.17, 0.78) | 0.33 (0.16, 0.55) | Z = 2.197 | 0.028 |

| FSH, M (Q1, Q3) | 54.72 (30.10, 80.45) | 65.94 (44.83, 91.84) | Z = –3.177 | 0.001 |

| T, M (Q1, Q3) | 0.48 (0.23, 0.73) | 0.52 (0.27, 0.70) | Z = –0.415 | 0.679 |

| PRL, M (Q1, Q3) | 226.30 (173.60, 306.40) | 211.30 (153.50, 275.50) | Z = 1.764 | 0.078 |

| E2, M (Q1, Q3) | 152.03 (18.35, 347.03) | 59.33 (18.35, 133.72) | Z = 4.871 | |

| TG, M (Q1, Q3) | 1.98 (1.38, 2.64) | 1.14 (0.78, 1.58) | Z = 7.889 | |

| TC, M (Q1, Q3) | 5.67 (4.89, 6.12) | 4.60 (4.15, 5.10) | Z = 8.110 |

Note: p-values

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Box plot showing the distribution of sex hormones, TG, and TC levels in perimenopausal women with and without breast nodules. The boxes show the IQR of the data, with the upper and lower “whiskers” indicating the range of variation in the data. ns represents no significant difference, * represents p-value

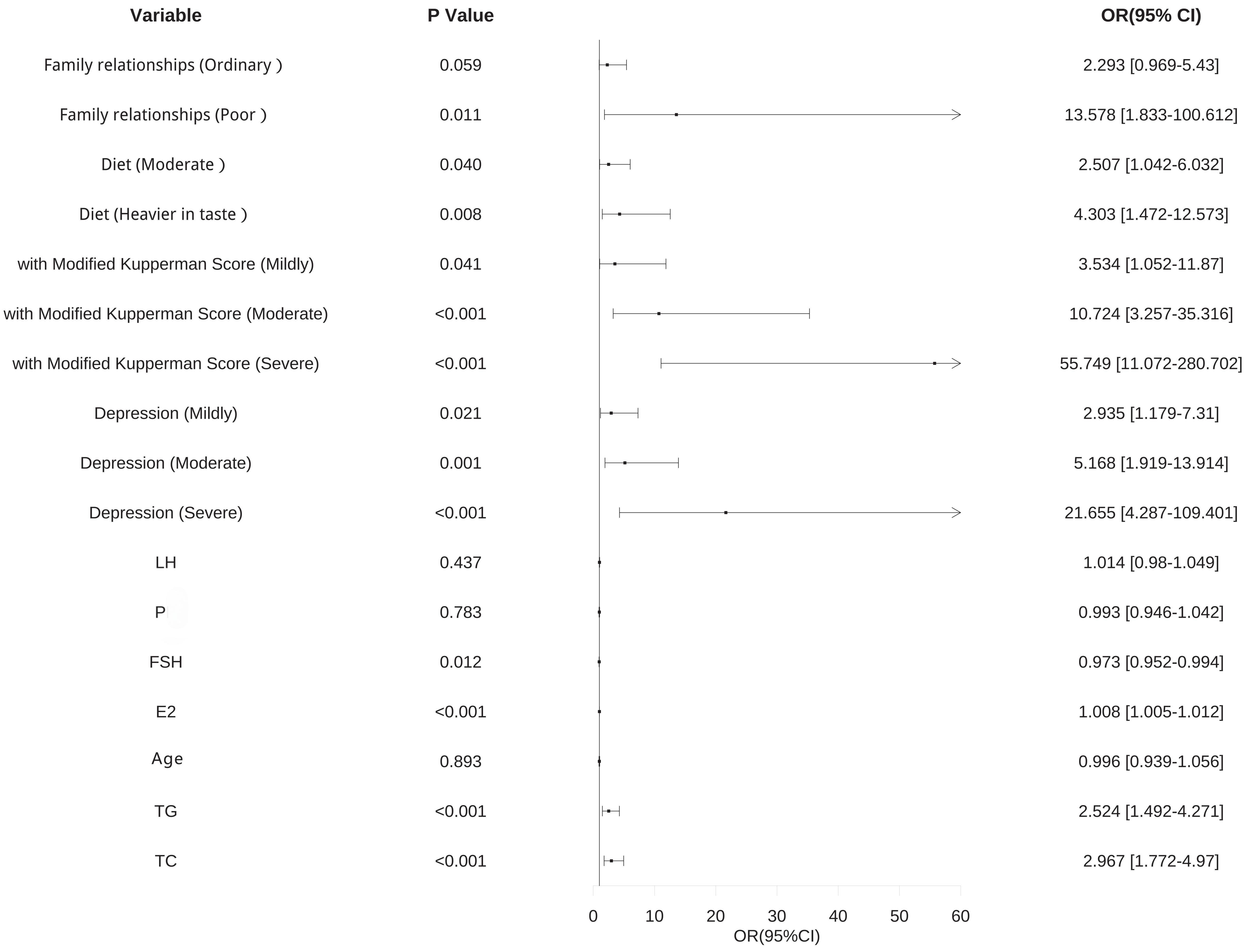

Logistic regression analysis was conducted with the presence of breast nodules as the dependent variable (Y), and age, family relationship, diet, modified Kupperman score, level of depression, P, FSH, PRL, E2, TG, and TC levels as the independent variables (X). The results indicated that family relationship, diet, modified Kupperman score, depression, E2, TG, and TC were identified as independent risk factors for the development of breast nodules in perimenopausal women. In contrast, high levels of FSH were identified as protective factors against breast nodules in perimenopausal women, with a statistically significant difference (p

| B | S.E. | Wald | p | VIF | Exp(B) | Exp(B) OR (95% CI) | ||

| Lower limit | Upper limit | |||||||

| LH | 0.013 | 0.017 | 0.604 | 0.437 | 1.787 | 1.014 | 0.980 | 1.049 |

| P | –0.007 | 0.025 | 0.076 | 0.783 | 1.041 | 0.993 | 0.946 | 1.042 |

| FSH | –0.027 | 0.011 | 6.325 | 0.012 | 1.822 | 0.973 | 0.952 | 0.994 |

| E2 | 0.008 | 0.002 | 25.672 | 1.114 | 1.008 | 1.005 | 1.012 | |

| Age | –0.004 | 0.030 | 0.018 | 0.893 | 1.034 | 0.996 | 0.939 | 1.056 |

| Family relationships (Harmony) | - | - | 8.767 | 0.012 | 1.068 | - | - | - |

| Family relationships (ordinary) | 0.830 | 0.440 | 3.564 | 0.059 | 2.293 | 0.969 | 5.430 | |

| Family relationships (poor) | 2.608 | 1.022 | 6.516 | 0.011 | 13.578 | 1.832 | 100.615 | |

| Diet (Light) | - | - | 7.850 | 0.020 | 1.049 | - | - | - |

| Diet (Moderate) | 0.919 | 0.448 | 4.213 | 0.040 | 2.507 | 1.042 | 6.032 | |

| Diet (Highly palatable) | 1.459 | 0.547 | 7.113 | 0.008 | 4.303 | 1.472 | 12.573 | |

| With modified Kupperman score (Normal) | - | - | 28.055 | 1.080 | - | - | - | |

| With modified Kupperman score (Mildly) | 1.262 | 0.618 | 4.169 | 0.041 | 3.534 | 1.052 | 11.871 | |

| With modified Kupperman score (Moderate) | 2.373 | 0.608 | 15.222 | 10.724 | 3.256 | 35.317 | ||

| With modified Kupperman score (Severe) | 4.021 | 0.825 | 23.768 | 55.749 | 11.072 | 280.712 | ||

| Depression (Normal) | - | - | 20.093 | 1.057 | - | - | - | |

| Depression (Mildly) | 1.077 | 0.466 | 5.350 | 0.021 | 2.935 | 1.179 | 7.310 | |

| Depression (Moderate) | 1.642 | 0.505 | 10.563 | 0.001 | 5.168 | 1.919 | 13.914 | |

| Depression (Severe) | 3.075 | 0.826 | 13.846 | 21.655 | 4.286 | 109.404 | ||

| TC | 0.926 | 0.268 | 11.903 | 0.001 | 1.182 | 2.524 | 1.492 | 4.271 |

| TG | 1.088 | 0.263 | 17.082 | 1.157 | 2.967 | 1.772 | 4.970 | |

| Constant | –10.546 | 2.299 | 21.044 | - | 0.000 | - | - | |

Note: p-values

B, regression coefficient; S.E., standard error; VIF, variance inflation factor; Exp(B), exponential of B; OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; LH, luteinizing hormone; P, progesterone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; E2, estradiol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Forest plot of risk factors for the occurrence of breast nodules in perimenopausal women. Visualization of the results presented in Table 6. OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; LH, luteinizing hormone; P, progesterone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; E2, estradiol; TC, total cholesterol; TG, triglyceride.

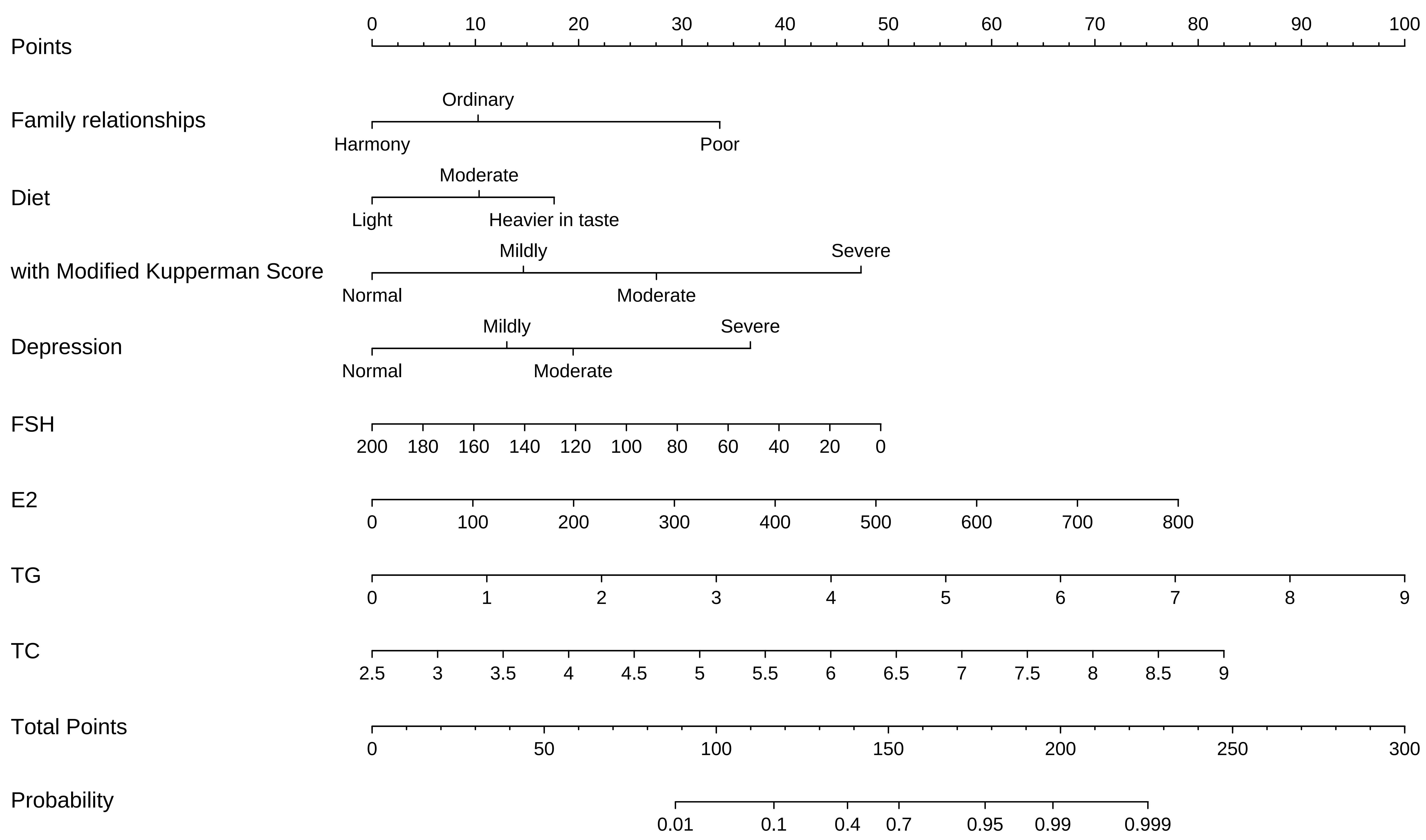

Using the multifactorial logistic regression model, a column-line graph model was developed to predict the risk of occurrence of perimenopausal breast nodules. This model identified the corresponding points of each variable on the respective axes of the graph, allowing for the calculation of an overall risk score for the occurrence of perimenopausal breast nodules. The horizontal axis indicated the corresponding scores for each variable, and summing these scores provided the total score on the risk axis. The predicted probability of perimenopausal breast nodules was derived from this total score, with the results depicted in Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3. Nomogram prediction model. The nomogram above is used to predict the occurrence of breast nodules in perimenopausal women based on family relationship, diet, modified Kupperman score, depression, E2, FSH, TG, and TC. The first row labelled “points” represents the score for each predictor variable. For any individual perimenopausal women, the total score can be calculated by summing the points for each predictor variables. The total score is then mapped to a linear score, which provides the predicted probability of developing breast nodules in perimenopausal women. E2, estradiol; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; TG, triglyceride; TC, total cholesterol.

The predictive validity of the nomogram prediction model for the occurrence of breast nodules during perimenopause was assessed by a goodness-of-fit curve. The results showed that for the modeling group,

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4. ROC curves for modeling group and validation group line graph prediction models. The blue lines represents the modelling group, and the red line represents the validation group. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AUC, area under the curve.

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5. The fitting curves of the nomogram prediction model for the modeling group and the validation group. The predictive validity of the column-line graph prediction model for breast nodules occurring during perimenopause was assessed by a goodness-of-fit curve. The results showed that for the training group

The risk factors affecting perimenopausal breast nodules are complex and still controversial. Perimenopause is a unique stage in a woman’s life, marking the transition from the mature functioning of the ovaries to a gradual decline, ultimately leading to their failure. With the decline in ovarian function, estrogen levels decrease, which can lead to a variety of physiological changes [14]. During this period, perimenopausal women often experience symptoms such as anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, endocrine imbalances, and metabolic disturbances. These symptoms, coupled with hormonal fluctuation, can contribute to an increased risk of breast nodules, potentially leading to malignancies. This not only exacerbates the economic burden on families and society but also negatively impacts the quality of life of perimenopausal women [15, 16]. Therefore, exploring the risk factors associated with perimenopausal breast nodules and implementing timely, targeted interventions are crucial for preventing the development of these nodules and improving patient prognosis.

This study suggests that poor family relationships may be an independent risk factor for the development of breast nodules. Women are prone to endocrine system dysfunction due to various factors, including their living environment, interpersonal relationships, and overall living conditions, leading to hormone secretion imbalances [17, 18, 19]. Some scholars suggest that women in the perimenopausal stage may experience emotional instability due to disharmonious family relations and increased stress, resulting in cerebral cortex disorders and the formation of endocrine imbalances, which could potentially induce mammary gland hyperplasia [20, 21, 22]. Study has also reported that harmonious family relationships may provide women with positive psychological effects, improving immune function stability, which in turn contributes to the protection of healthy breast tissue [23]. These findings are consistent with the results of our analysis. Therefore, harmonious family relationships can offer emotional support and a stable environment, helping to reduce stress and anxiety in women, ultimately lowering the risk of breast nodules.

Study has confirmed that dietary habits play an important role in influencing the risk of breast nodules [24]. This study highlights that perimenopausal women with a preference for salty and sweet foods are at a higher risk of developing breast nodules. The study reports that long-term intake of high-salt and high-sugar foods can stimulate the esophageal mucosa and induce a chronic inflammatory state in the body, thereby increasing the risk of developing breast nodules. In contrast, perimenopausal women who prefer a light diet, rich in fresh vegetables abundant in vitamins, benefit from these nutrients. Vitamins are crucial in inhibiting the oxidation of unsaturated fatty acids, which helps protect against excessive hyperplasia of breast target cells and reduces the risk of breast nodules [25, 26, 27].

Depression is a major public health issue, with the lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders among females reaching as high as 40% [28]. Perimenopause is regarded as a critical period for the development of depression. Our study revealed that the severity of depression in perimenopausal women is positively associated with an increased risk of developing breast nodules, which aligns with the findings of a cross-sectional study conducted by Long et al. [2]. However, the direct signaling network between breast nodules and depression remains inconclusive. Some scholars suggest that depression is associated with the chronic, abnormal activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in elevated levels of catecholamines, which may promote mammary gland hyperplasia and carcinogenesis [29]. Additionally, study has demonstrated that long-term anxiety, tension, and worry, especially under the influence of a negative emotional state, can increase prolactin secretion, disrupt estrogen metabolism, elevate E2 levels in the body, and consequently contribute to the development of breast diseases [30]. The modified Kupperman score is a tool employed to assess the severity of perimenopausal syndrome, including symptoms such as hot flashes, night sweats, insomnia, memory loss, and inattention in perimenopausal women. This study identified that perimenopausal syndrome serves as an independent risk factor for the development of breast nodules in this population. A case-control study revealed that, with the intervention of phytopreparations, the alleviation of perimenopausal-related symptoms significantly decreased breast tissue density, thereby reducing the diameter and number of cysts. This finding suggests that perimenopausal syndrome is one of the influencing factors for the development of breast nodules [31], which aligns with the results of our study. In clinical practice, it is crucial to promptly recognize the symptoms associated with perimenopause and implement timely interventions to minimize the incidence of breast nodules.

High estrogen levels can stimulate breast tissue proliferation, leading to hyperplasia of the breast duct epithelium, lobules, and fibrous connective tissue [32]. Scholars have confirmed that postmenopausal breast nodule patients exhibit higher levels of E2 [33], which is consistent with the findings of this study, indicating that high E2 levels are independent risk factors for perimenopausal breast nodules. HRT, proposed in recent years to address issues faced by perimenopausal women [34], has been suggested by a case-control study to potentially increase the risk of proliferative breast disease [35]. High E2 levels are not conducive to controlling perimenopausal breast nodules and may even increase the likelihood of their deterioration. Additionally, we analyzed the relationship between FSH and perimenopausal breast nodules using multivariate logistic regression, which revealed that a high level of FSH act as a protective factor against the development of perimenopausal breast nodules. The mechanism may involve increased FSH levels in perimenopausal women suppressing estrogen production through a negative feedback loop, thereby inhibiting the growth of breast cancer cells [36]. Therefore, the decision regarding HRT for perimenopausal women should be based on dynamic monitoring of sex hormone levels and routine breast ultrasounds. This study also indicated that TC and TG are independent risk factors for perimenopausal breast nodules. As hormone levels change and the basal metabolic rate declines with age, perimenopausal women become more susceptible to excessive intake of sugars and fats, leading to lipid accumulation and elevated blood lipids [37]. Study has shown that breast cell lesions are associated with lipid metabolism, primarily because pathological breast tissue is surrounded by a large number of fat cells within the mammary gland [38]. The microenvironment of these tissues contains significant amounts of fatty acids produced by fat cells through the TC cycle, contributing to breast cell lesions [39, 40]. The nomogram prediction model, constructed based on the results of multivariate analysis, was evaluated for its predictive validity regarding the occurrence of breast nodules in perimenopausal patients using fit curves and ROC curves. All evaluations indicate that the model exhibits high predictive validity and discriminative power, enabling early identification of perimenopausal breast nodules and facilitating timely intervention. In conclusion, factors such as tense family relationships, poor dietary and taste habits, severe menopausal syndrome, higher depression levels, high estrogen levels, and elevated blood lipid levels are all independent risk factors for the development of breast nodules in perimenopausal women. Conversely, high levels of FSH serve as a protective factor. This study provides valuable insights and guidance for the prevention and treatment of breast nodules, deepening our understanding of this common issue and supporting the implementation of early interventions to improve breast health in perimenopausal women.

This study initiates an analysis of the factors influencing the development of breast nodules in perimenopausal women. However, it is critical to acknowledge limitations, including the potential for self-report bias in the questionnaire data. Future research should aim to expand the sample size, adopt a longitudinal study design, incorporate additional influencing factors, and conduct comparative analyses across different regions and ethnic groups. By implementing these improvements, the precision and reliability of the findings will be enhanced, thereby providing more nuanced and actionable guidance for the prevention and treatment of breast nodules in perimenopausal women.

This study has thoroughly investigated the factors contributing to the development of breast nodules in perimenopausal women. It identified poor family relationships, unhealthy dietary habits, severe menopausal symptoms, severe depression, elevated estrogen levels, and increased blood lipid levels as independent risk factors for he development of breast nodules in perimenopausal women. Moreover, high FSH levels were found to act as a protective factor for the development of perimenopausal breast nodules. The developed predictive model demonstrated strong predictive capability and discriminative power, providing valuable insights for the early clinical prediction of breast nodules in perimenopausal women. These findings offer crucial guidance for the prevention and treatment of breast nodules, contributing to a deeper understanding of this prevalent issue. They also support timely interventions to enhance breast health in perimenopausal women.

ROC, receiver operating characteristic; LH, luteinizing hormone; P, progesterone; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; E2, estradiol; BMI, body mass index; T, testosterone; PRL, prolactin.

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy concerns related to human participant data.

XL was responsible for the questionnaire and completed the statistical analysis and wrote the majority of the manuscript. JM supervised the statistical analysis process, and critically revised the manuscript. KL handled the statistical analysis and contributed to part of the manuscript. LZ, GL and DW participated in the field investigation and managed the data cataloging. LY orchestrated and directed the project, meticulously reviewing the manuscript before giving his final approval. Each author is responsible for the content of the published paper. All authors contributed to the editorial changes to the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All the authors were fully involved in this work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of The Affiliated Hospital of Guizhou Medical University, People’s Republic of China, approved the study (Approval Number: 2022no.251).

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This project was supported by the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (qkhjc-ZK[2023]yb351).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.