1 Department of Gynecology, Changning Maternity and Infant Health Hospital, 200000 Shanghai, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

To examine the effect of tubal flushing on the fertility outcome of patients with tubal ectopic pregnancy (EP) undergoing salpingectomy.

This prospective cohort study included 93 patients who received unilateral salpingectomy for tubal EP. Tubal flushing via hysteroscopic hydrotubation was performed after surgery on only 42 patients in the cohort. All patients were followed up for their fertility outcomes by phone interview.

Intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) was documented in 48 cases. The cumulative IUP rate was 64.6% in the patients who received tubal flushing, and 54.7% in the patients without tubal flushing (p = 0.071). The median time from salpingectomy to IUP was 13.0 months in the patients with tubal flushing and 27.1 months in those without tubal flushing (p = 0.007). Recurrent ectopic pregnancy (REP) was documented in three (7.1%) of the patients who received tubal flushing and two (3.9%) that did not (p = 0.823).

Tubal flushing via hysteroscopic hydrotubation after unilateral salpingectomy may improve subsequent IUP after EP but cannot prevent REP.

The study protocol was registered to the Chinese Clinical Trial Registry at https://www.chictr.org.cn/ (Identifier No.: ChiCTR2100052941).

Keywords

- ectopic pregnancy

- tubal flushing

- intrauterine pregnancy

- recurrent ectopic pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy (EP) is one of the most common gynecological diseases, which occurs when a fertilized oocyte implants and grows outside the uterine cavity. The incidence of EP is 1–2% in natural pregnancies [1], and 2–3% in the women receiving assisted reproductive technology [2, 3]. More than 95% of ectopic pregnancies occur in the fallopian tubes. Tubal pregnancy is closely related to chronic pelvic inflammatory disease, cigarette smoking, pelvic surgery, previous EP, and use of intrauterine contraceptives [4].

In some developed areas, such as Shanghai, China, the diagnosis and treatment of ectopic pregnancy is becoming more standardized. Gynecologists are paying more attention to how to promote fertility after the treatment of ectopic pregnancy. No generally accepted conclusion has been reached about how to improve the pregnancy rate after ectopic pregnancy and reduce recurrent ectopic pregnancy (REP). The tubal patency after treatment of ectopic pregnancy is affected, possible due to morbid factors, surgical operations, or ectopic pregnancy lesions [5]. Tubal patency affects the future success of pregnancy [6]. We suggested that better tubal patency may improve the natural pregnancy rate after EP and reduce REP.

Tubal flushing is an important method to evaluate tubal patency and treat tubal obstruction. For subfertile women, tubal flushing can increase the intrauterine pregnancy (IUP) rate by improving tubal patency as tubal flushing may remove the mucus plug or mild adhesions in the fallopian tubes [7, 8]. Tubal flushing has been widely used in infertile women to improve the rate of IUP. Therefore, we provided tubal flushing via hysteroscopic hydrotubation after unilateral salpingectomy for patients with ectopic pregnancy to examine its effect on subsequent IUP.

The patients who underwent laparoscopic unilateral salpingectomy for tubal pregnancy from January 2018 to December 2019 at Shanghai Changning Maternity and Infant Health Hospital were included in this prospective cohort study. The study protocol was registered to Chinese Clinical Trial Registry at chictr.org.cn (Identifier No.: ChiCTR2100052941). All the enrolled patients signed informed consent before surgery.

All the patients undergoing unilateral salpingectomy due to tubal pregnancy were identified from the electronic medical record system via the code of clinical diagnosis. The patients were enrolled based on the following criteria: (1) normal uterus and ovaries evaluated by ultrasonography and intraoperative exploration; (2) undergoing unilateral salpingectomy without surgical complication; (3) serum

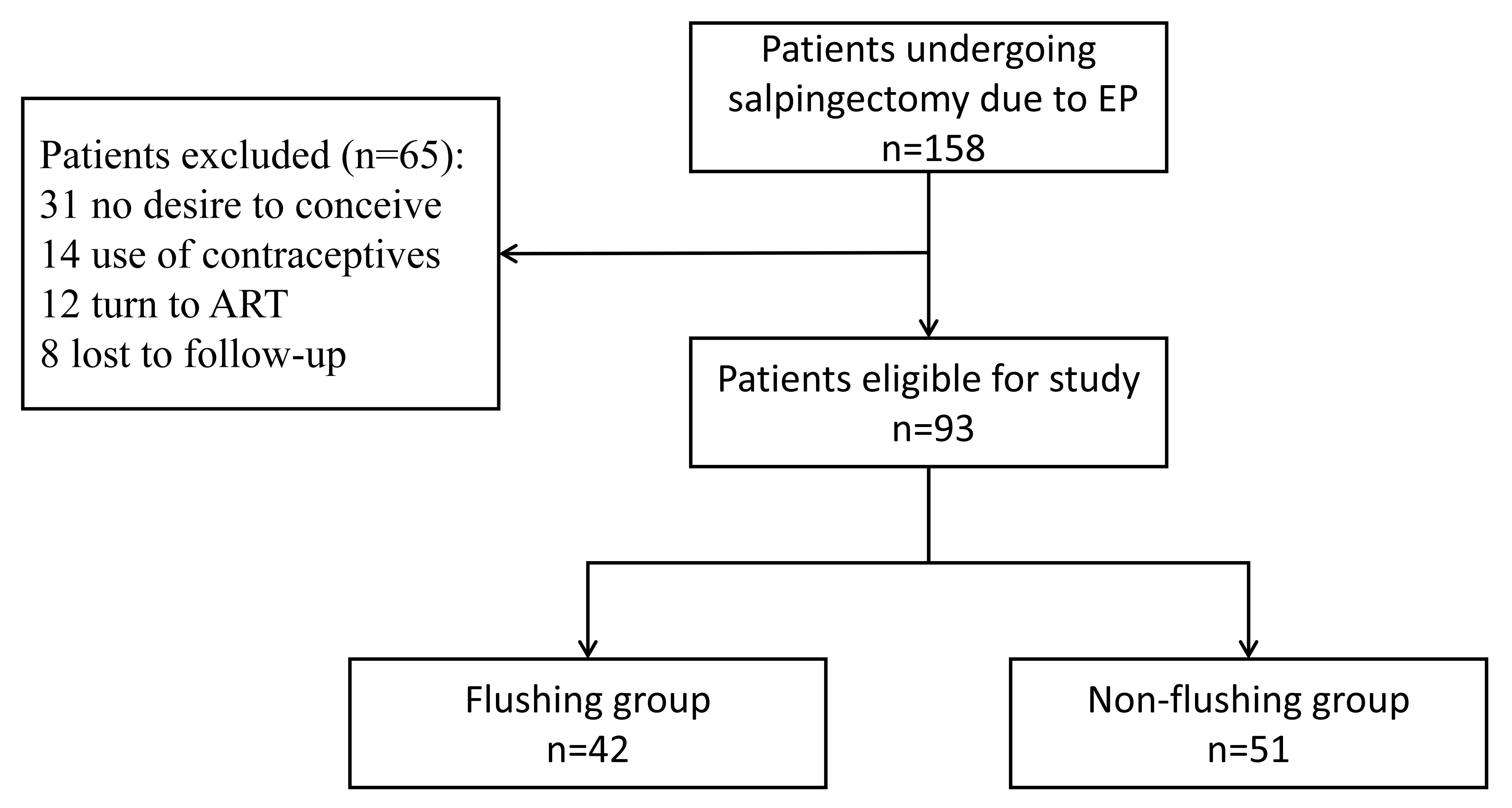

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Patients enrollment. The patients eligible for this cohort study based on salpingectomy due to EP and tubal flushing. ART, assisted reproductive technology; EP, ectopic pregnancy.

Demographic data of patients such as age, gravity, parity, amenorrhea time, serum

The patients were followed up by phone interviews with questions focusing on fertility outcomes after EP, including the diagnosis of IUP and REP. The time from salpingectomy for EP to subsequent pregnancy outcome was recorded.

Hysteroscopic hydrotubation, as a method for flushing oviducts, was performed under intravenous anesthesia in the outpatient setting [9]. Normal saline solution (0.9% sodium chloride) was used for distending the uterine cavity. A hysteroscope (J0122, SHENDA Endoscope Co., Ltd., Shenyang, Liaoning, China) with an operating channel was inserted to examine the uterine cavity and endometrium. After examination, a

SPSS 13.0 statistical software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used to analyze the data. The REP and IUP were used to evaluate the fertility outcome. The cumulative IUP rate and the median time from salpingectomy to IUP were calculated and analyzed using the Kaplan-Meier method, with the person-time being the time to pregnancy, which is the cumulative period during which a patient desired to conceive until she became pregnant. The curves were analyzed by log-rank tests for univariate analysis. The REP rates were compared between groups using the Fisher exact test. The measurement data were compared by t-test. Data that do not conform to normal distribution were analyzed using nonparametric tests. The count data were analyzed using Chi-square test. p

The patients undergoing tubal flushing were comparable to those without tubal flushing in terms of amenorrhea days,

| Tubal flushing (n = 42) | No tubal flushing (n = 51) | p value | ||

| Age (years) | 29.9 | 30.3 | 0.718 | |

| Gravity (%) | ||||

| 0 | 17 (40.5) | 13 (25.5) | 0.124 | |

| 25 (59.5) | 38 (74.5) | |||

| Parity (%) | ||||

| 0 | 36 (85.7) | 39 (76.5) | 0.261 | |

| 6 (14.3) | 12 (23.5) | |||

| Amenorrhea (days) | 50.2 | 49.0 | 0.612 | |

| Mass size (mm) | 30.4 | 31.3 | 0.991* | |

| Mass location (%) | ||||

| Left | 26 (61.9) | 27 (52.9) | 0.385 | |

| Right | 16 (38.1) | 24 (47.1) | ||

| Serum | 2812.9 | 3907.0 | 0.865* | |

| Operation time (minutes) | 57.8 | 52.9 | 0.244 | |

| Hematocele (mL) | 144.33 | 165.7 | 0.548* | |

| Intraoperative blood loss (mL) | 10.7 | 7.8 | 0.152* | |

Data are presented as mean

The medium time of follow-up was 17.9 months (range 4.3–32.3 months). IUP was documented in 48 cases. Specifically, IUP occurred 0–6 months after surgery in 3 (6.3%) cases, 7–12 months after surgery in 28 (58.3%) cases, 12–24 months in 15 (31.3%) cases, and 24–36 months in 2 (4.2%) cases (p = 0.000).

The overall cumulative IUP rate was 62.5%; specifically, 64.6% in the tubal flushing group, and 54.7% in the no tubal flushing group (p = 0.071) (Table 2).

| No. of patients | No. of IUP | Cumulative IUP rate* | p value | |

| Tubal flushing | 42 | 26 | 0.646 | 0.071 |

| No tubal flushing | 51 | 22 | 0.547 | |

| Total | 93 | 48 | 0.625 |

IUP, intrauterine pregnancy. *, cumulative IUP rate was calculated using Kaplan-Meier method, and analyzed using Chi-square test.

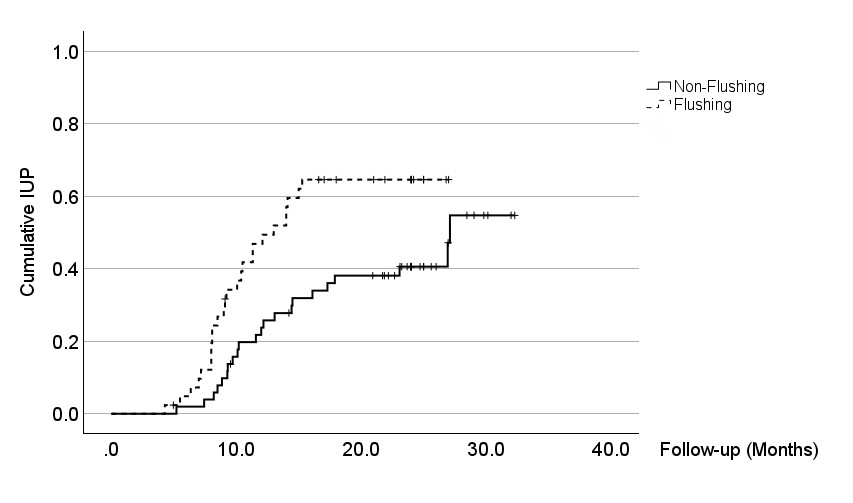

The median time from salpingectomy to IUP was 13.0 months in the tubal flushing group and 27.1 months in the no tubal flushing group. The difference between groups is significant (p = 0.007) shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. Cumulative IUP rate in groups. The median time from salpingectomy to IUP was 13.0 months in the tubal flushing group and 27.1 months in the no tubal flushing group. The difference between groups is significant (p = 0.007). IUP, intrauterine pregnancy.

REP was documented in 3 (7.1%) of the patients receiving tubal flushing and 2 (3.9%) of the patients without tubal flushing. The difference between groups was non significant (p = 0.823).

Ectopic pregnancy is a common gynecological emergency among reproductive-aged women. The management of EP should focus on not only the rapid recovery of the disease but also on preserving subsequent fertility, especially for nulliparous patients. Gynecologists should provide individualized therapy for patients to increase subsequent fertility rate according to the

The function of the fallopian tubes may be impaired after EP. Hu et al. [16] found that of patients with infertility treated for tubal pregnancies, 92.11% (35/38) suffered bilateral or unilateral oviduct exceptions, such as adhesions around or distorted tubal anatomy, closure or adhesion in the umbrella end, and lumen block. The patency of fallopian tubes may be impaired after recovery. Seyedoshohadaei et al. [17] found that among patients undergoing methotrexate treatment for EP, lower

Tubal flushing is an assay of tubal patency tests, including hysterosalpingogram, transvaginal ultrasound salpingography, and hysteroscopic hydrotubation, which is a commonly used diagnostic investigation and essential for infertile women. Tubal flushing is not only a diagnostic test but also a treatment approach for infertile women in clinical practice. Wang et al. [8] conducted a meta-analysis about the effect of tubal flushing on infertility and found that tubal flushing may increase the chance of live birth and clinical pregnancy. Tubal flushing with oil-soluble contrast media may increase clinical pregnancy rates (17–37% vs. 9%) [20, 21]. The possible explanation is that mechanical flushing can remove the debris or mucus plugs out of the fallopian tubes, therefore unblocking the undamaged tubes. The debris may block the fallopian tubes and hinder embryo transport along the fallopian tube. Additionally, the contrast media could also enhance ciliary motility [22].

Hysteroscopic hydrotubation is not only a tubal flushing method, but also is useful in evaluating tubal patency and uterine cavity more visually and accurately than hysterosalpingography and transvaginal ultrasonography [9, 23]. Lei et al. [24] reported that hysteroscopic hydrotubation with a solution consisting of hydrocortisone, gentamicin, and procaine had a therapeutic effect on tubal blockage. A 2-year prospective randomized controlled trial conducted by Saaqib et al. [25] reported that tubal hydrotubation can increase the conception rate (20/64 vs. 4/64) and decrease the time to achieve pregnancy.

The effect of hysteroscopic hydrotubation on the fertility outcome after EP is rarely reported. This is a single-center prospective cohort study conducted in a gynecological minimally invasive medical unit which treats more than 220 cases of EP every year. We have made efforts to improve the natural IUP rate after treatment for EP. The results of this study suggested that hysteroscopic hydrotubation might improve the natural pregnancy rate and significantly shorten the time to pregnancy after unilateral salpingectomy for EP. Alternatively, we only need to evaluate the patency of the remaining oviducts for these patients undergone salpingectomy for EP. Accurate evaluation of the target tube could avoid excessive liquid pressure on other interstitial tissues of oviducts and so reduce the occurrence of fistula. The procedure of hysteroscopic hydrotubation is usually short, safe and has few complications. Vaginal bleeding and temperature need to be monitored after the procedure. We have not had any cases of uterine perforation during hysteroscopic hydrotubation.

The estimated incidence of REP is 10–27% [26]. The risk factors for REP include impairment of oviducts, pelvic infection, prior pelvic surgery, salpingitis, and a history of infertility [26, 27]. A retrospective case-control study conducted by Zhang et al. [28] reported that among various treatments for EP, such as expectant, medical, salpingectomy, and salpingostomy, only salpingostomy increased the risk of REP. The findings of Wang et al. [29] also support this conclusion. Another five-year follow-up cohort study on REP [30] revealed that the overall REP rate was 18.9% (41/217). Among the 143 surgically treated cases, salpingectomy (versus salpingostomy) and laparoscopy (versus laparotomy) were associated with a lower risk of REP. All the patients enrolled in our study underwent unilateral salpingectomy for EP. REP was found in 5 patients (5.4%), the incidence of which was similar than previous reports. It seems that hysteroscopic hydrotubation does not reduce REP rate.

The limitations of this study include small sample size, single-center, and prospective data, which may bias the results and influence the stratified analyses. The effect of hysteroscopic hydrotubation on infertility is still controversial. We found a positive effect of hysteroscopic hydrotubation on the fertility outcome in patients after unilateral salpingectomy for EP. However, more research is required to examine the real value of hysteroscopic hydrotubation in patients receiving various treatments (e.g., expectant management, conservative surgery, or pharmacotherapy) for EP.

In conclusion, tubal flushing via hysteroscopic hydrotubation has been proven to be useful in improving reproductive outcomes. We have been providing hysteroscopic hydrotubation for women after EP for years. Our experience summarized in this report suggests that postoperative hysteroscopic hydrotubation has a positive effect on the fertility outcome after unilateral salpingectomy for EP, evidenced by a earlier conception, but it did not prevent REP.

EP, ectopic pregnancy; IUP, intrauterine pregnancy; REP, recurrent ectopic pregnancy.

All data reported in this paper will also be shared by the lead contact upon request.

WZ and CM designed the research study. JL performed the research. JS follow-up and acquist data; WZ, YL and YS analyzed the data. WZ and JL wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

We obtained informed approval from the ethics institution from Changning Maternity and Infant Health Hospital, Shanghai, China. The ethics approval number is CNFBLLKT-2021-020. The study protocol was registered to Chinese Clinical Trial Registry at chictr.org.cn (Identifier No.: ChiCTR2100052941), and all of the participants provided signed informed consent.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.