1 Department of Fetal Medicine, Jiaxing Maternity and Children Health Care Hospital, Affiliated Women and Children Hospital, Jiaxing University, 314000 Jiaxing, Zhejiang, China

Abstract

This study aimed to explore the differences in the detection rates of chromosomal abnormalities in simple and complex congenital heart disease (CHD) and the association between these rates and genetic factors.

A total of 211 fetuses diagnosed with CHD through prenatal ultrasound at the fetal medicine unit of Zhejiang Jiaxing Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital from July 2017 to December 2023 were retrospectively analyzed. Cases were classified as simple or complex cardiac malformations. Chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) was used as the primary genetic assessment following invasive sampling in all CHD cases. Clinical exome sequencing (ES) or Trio exome sequencing (Trio-ES) was applied prenatally when the CMA results were nondiagnostic.

Of the 211 fetuses, 62.6% and 37.4% presented with simple and complex malformations, respectively. The CMA reported an overall positive rate of 19.0% across all cases: 11.4% for simple cardiac malformations and 31.6% for complex cardiac malformations. The detection rate of chromosomal abnormalities was significantly higher in complex cases (22.8%) than in simple malformations (6.1%; p < 0.001). Among the isolated CHD cases, 8.7% exhibited chromosomal abnormalities, predominantly in complex malformations (20.0% vs. 2.9% for simple malformations; p < 0.001). Meanwhile, the rate was high (23.5%) in non-isolated CHD, but simple and complex malformations did not differ significantly. ES was performed for 32 cases with negative CMA results. One pathogenic (P)/likely pathogenic (LP) variant was identified through Trio-ES in simple malformations, while two P/LP variants were detected in complex malformations.

Differentiated genetic assessments could be included in prenatal diagnosis, because complex CHD correlated strongly with chromosomal and genetic anomalies rather than with simple malformations. This finding, although based on a small population, suggests that non-cardiac anomalies may be important indicators for genetic testing regardless of the complexity of heart defects. Therefore, genetic testing could be offered to patients with simple or isolated CHD.

Keywords

- simple cardiac malformation

- complex cardiac malformation

- chromosome microarray

- exome sequencing

- prenatal diagnosis

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is the most common congenital malformation, and its incidence is approximately 5–8 per 1000 live births [1, 2]. This malformation not only affects the quality of life of patients but also leads to severe cardiovascular complications; it may even become life-threatening. In prenatal diagnosis, fetal CHD can be primarily detected by traditional ultrasound examination. Simple CHD can be cured through surgery, thereby allowing patients to achieve a normal and healthy life. For complex CHD, a small portion of cases with poor prognosis may not respond well to surgery, but most patients can attain a good quality of life after surgery and live as healthily as individuals without a heart disease. However, genetic abnormalities frequently result in poor outcomes [3, 4], thereby highlighting the importance of genetic testing. Recently, with advancements in genomic technologies, the use of chromosomal microarray analysis (CMA) and exome sequencing (ES) in prenatal diagnosis has increased [5, 6, 7, 8]. CMA offers significantly enhanced resolution for detecting copy number variations (CNVs), enabling the identification of even submicroscopic alterations that are typically under 5–10 Mb in size [9]. CMA has been established as a gold standard in prenatal genetic testing, offering unrivaled sensitivity for detecting CNVs underlying fetal developmental delay and structural malformations [10]. The diagnostic value of CMA for CHDs with different cardiac phenotypes and extracardiac abnormalities has been evaluated [11]. ES has revolutionized diagnostic protocols by providing comprehensive analysis of the protein-coding genome in fetuses with CHDs [12]. These techniques can efficiently detect microvariations and single-gene mutations in the genome; thus, they can enhance the diagnostic accuracy and molecular genetic understanding of fetal CHD.

Despite the existence of numerous studies in this area, simple and complex CHD remain poorly understood. Previous studies focused on different aspects or did not employ essential methodologies to answer the research questions posed in this study. Our study aims to compare complex cardiac malformations, which have two or more cardiovascular structural abnormalities, with simple cardiac malformations, which have only one cardiovascular structural abnormality, to help provide the appropriate prenatal genetic testing.

In this retrospective study, 211 pregnant women diagnosed with prenatal CHD were recruited from the fetal medicine unit at Zhejiang Jiaxing Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital between July 2017 and December 2023. Fetal echocardiography reports were used to classify the CHD cases into simple and complex malformations based on the number and severity of cardiovascular structural abnormalities. For instance, cases with a single structural defect, such as a ventricular septal defect (VSD) or an atrial septal defect (ASD), were classified as simple malformations. Conversely, cases with two or multiple defects or severe abnormalities, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome or tetralogy of Fallot, were categorized as complex malformations. Cases with concurrent extracardiac structural malformations were not classified separately; instead, they were categorized on the basis of the number of cardiovascular structural abnormalities. All echocardiography reports were reviewed by two independent pediatric cardiologists to ensure the accuracy of the classification. Discrepancies in classification were resolved through a consensus.

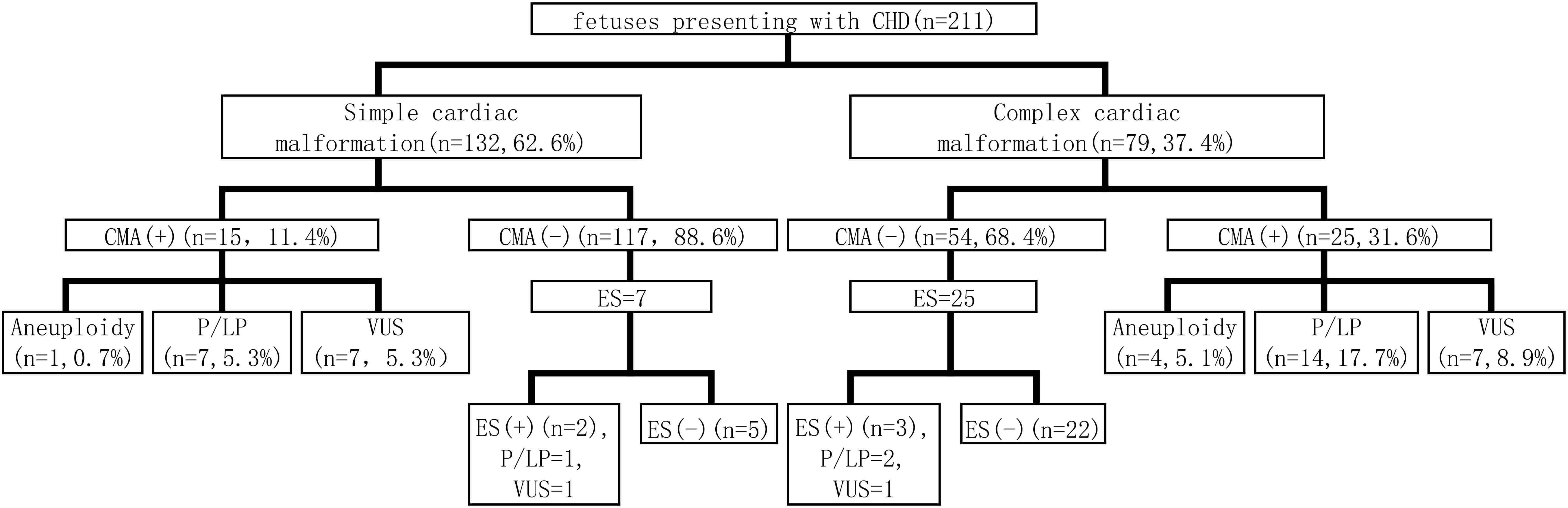

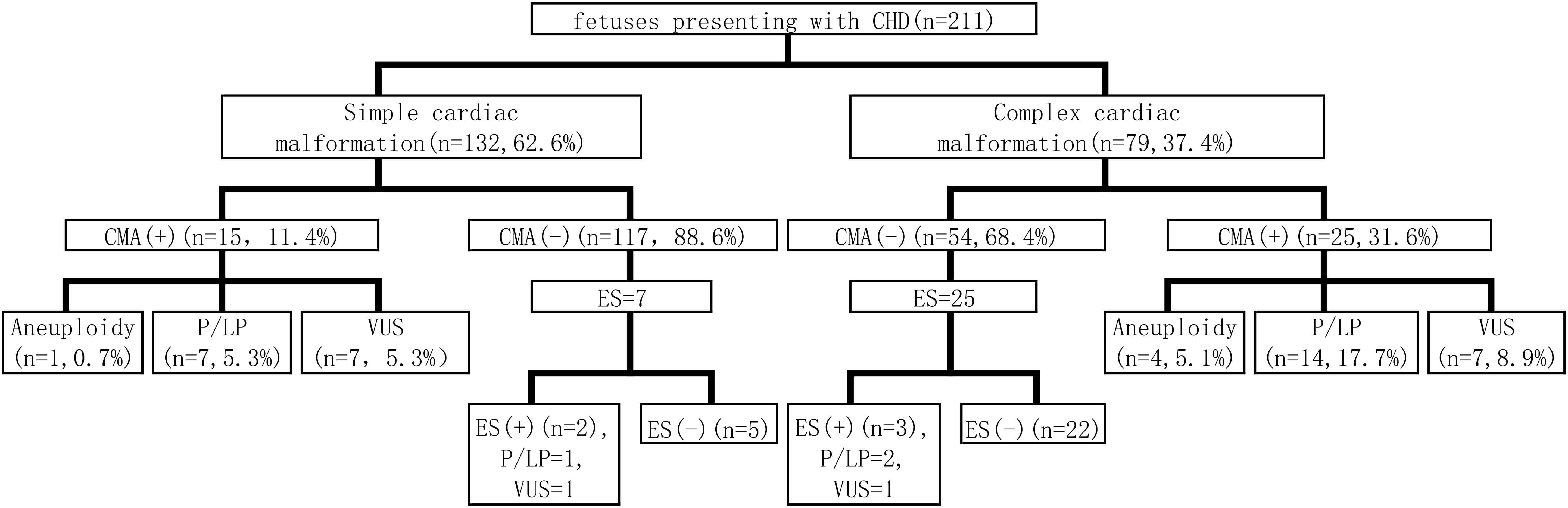

For all CHD cases, CMA served as the primary genetic assessment following invasive sampling. Clinical exome sequencing or Trio exome sequencing (Trio-ES) was applied prenatally when CMA results were non-diagnostic (exclusive variants of uncertain significance (VUS)). The process of prenatal diagnosis is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Work-up flow of prenatal diagnosis. CHD, congenital heart disease; CMA, chromosomal microarray analysis; ES, exome sequencing; P, pathogenic; LP, likely pathogenic; VUS, variants of uncertain significance.

Amniotic fluid samples (10 mL) were collected from pregnant participants, and

genomic DNA was isolated using the QIAamp DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

Genomic profiling was conducted on the Affymetrix CytoScan 750K platform (Santa

Clara, CA, USA), integrating 550,000 CNV and 200,000 Single Nucleotide Polymorphism (SNP) probes that provide

uniform genome-wide coverage at

The identified CNVs were annotated against GRCh37/hg19 and interpreted using major databases (DGV, DECIPHER, ClinGen, and OMIM). Clinical classifications were compliant with the American College of Medical Genetics (ACMG) guidelines, applying a five-tier system: pathogenic (P), likely pathogenic (LP), VUS, likely benign, and benign. The P/LP CNVs were repeat tested.

ES encompassing about 4000 genes associated with Mendelian diseases was performed using the MGIEasy Exome Hybrid Capture V2 kit (BGI Genomics, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China). A series of experimental steps, including nucleic acid extraction, library construction, Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) reactions, and pooling, was performed using the MGISP-100 automated nucleic acid extraction and library preparation instrument. Sequencing was conducted on the MGISEQ-2000 gene sequencer (MGI Tech, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China) by utilizing the optimized combinatorial probe-anchor synthesis (cPAS) technology and the enhanced DNA nanoball (DNB) core sequencing technology. Results were then analyzed and interpreted using the BGI HALOS integrated genetic testing system. Read alignment against the human reference genome (hg19/GRCh37, UCSC assembly) was performed by Burrows-Wheeler Aligner (BWA), and duplicates were removed. The Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) was then used to conduct the following: base quality score recalibration; variant calling for single nucleotide polymorphisms, insertions, and deletions (SNVs/INDELs); and genotyping. ExomeDepth was utilized for exon-level CNV detection. Variant pathogenicity was classified following the guidelines for interpreting sequence variants established by the ACMG and the Association for Molecular Pathology [15]. All variants were subjected to Sanger confirmation.

Group differences in prenatal genetic testing yield for CHD were assessed using

chi-square tests and Fisher’s exact test was used for subgroups with small

expected counts, and statistical significance was defined as p

Of the 211 fetuses diagnosed with congenital heart disease through prenatal ultrasound, 62.6% (132/211) had simple cardiac malformations, while 37.4% (79/211) had complex malformations. Isolated CHD comprised 75.8% (160/211) of cases, while non-isolated CHD associated with extracardiac malformations or soft markers constituted 24.2% (51/211). Furthermore, 65.6% (105/160) and 34.4% (55/160) of cases of isolated CHD were classified as simple and complex cardiac malformations, respectively. Of the non-isolated CHD cases, 52.9% (27/51) and 47.1% (24/51) were classified as simple and complex cardiac malformations, respectively. Among these cases, 52.9% (27/51) and 33.3% (17/51) were linked to soft markers and structural anomalies, respectively, and 13.7% (7/51) were related to both conditions.

All cases underwent prenatal CMA through which chromosomal aneuploidy and P/LP CNVs were identified as chromosomal abnormalities. The CMA results showed that 19.0% (40/211) of the cases had CNVs, including 11.4% (15/132) simple cardiac malformations and 31.6% (25/79) complex cardiac malformations (Fig. 1). The overall rates of chromosomal abnormalities were 12.3% (26/211), with 6.1% (8/132) in simple cardiac malformations and 22.8% (18/79) in complex cardiac malformations. In cases of simple cardiac malformations, 0.7% (1/132) had chromosomal aneuploidy, whereas 5.3% (7/132) exhibited P/LP CNVs. In cases of complex cardiac malformations, 5.1% (4/79) showed chromosomal aneuploidy, and 17.7% (14/79) presented with P/LP CNVs (Table 1). Among the five cases with chromosomal karyotype abnormalities, four were trisomy 21 and one was trisomy 18. Among P/LP CNVs, the most common was 22q11.21 deletion detected in 8 of 21 cases, which were associated with complex cardiac malformations.

| CHD groups | Total chromosomal abnormalities (%) | Aneuploidy (%) | P/LP CNV (%) | VUS (%) |

| Simple cardiac malformation (n = 132) | 8 (6.1%) | 1 (0.8%) | 7 (5.3%) | 7 (5.3%) |

| Complex cardiac malformation (n = 79) | 18 (22.8%) | 4 (5.1%) | 14 (17.7%) | 7 (8.9%) |

| Total (n = 211) | 26 (12.3%) | 5 (2.4%) | 21 (9.9%) | 14 (6.6%) |

| Simple cardiac malformation vs. Complex cardiac malformation | 0.157 | 0.007 | 0.317 |

CNV, copy number variation.

Among the 160 cases of isolated CHD, 8.7% (14/160) had chromosomal abnormalities. Specifically, 2.9% (3/105) of simple cardiac malformations involved P/LP CNVs. For complex cardiac malformations, 1.8% (1/55) and 18.2% (10/55) had chromosomal aneuploidy and P/LP CNVs, respectively (Table 2). Of the 51 cases of non-isolated CHD, chromosomal abnormalities were found in 23.5% (12/51) cases. Among them, 3.7% (1/27) of simple cardiac malformations were due to chromosomal aneuploidy, and 14.8% (4/27) had P/LP CNVs. For complex cardiac structural malformations, 12.5% (3/24) were associated with chromosomal aneuploidy, while 16.7% (4/24) had P/LP CNVs. Among CHD with a soft marker, 14.8% (4/27) had chromosomal abnormalities. For those with structural anomalies, 35.3% (6/17) had chromosomal abnormalities, while cases with soft marker and structural anomalies had a 28.6% (2/7) rate of chromosomal abnormalities (Table 3).

| CHD group | Total chromosomal abnormalities (%) | Aneuploidy (%) | P/LP CNV (%) | VUS (%) |

| Simple cardiac malformation (n = 105) | 3 (2.9%) | 0 | 3 (2.9%) | 3 (2.9%) |

| Complex cardiac malformation (n = 55) | 11 (20.0%) | 1 (1.8%) | 10 (18.2%) | 6 (10.9%) |

| Total (n = 160) | 14 (8.7%) | 1 (0.6%) | 13 (8.1%) | 9 (5.6%) |

| Simple cardiac malformation vs. Complex cardiac malformation | 0.333 | 0.003 | 0.072 |

| CHD group | Total chromosomal abnormalities (%) | Aneuploidy (%) | P/LP CNV (%) | VUS (%) |

| Total (n = 51) | 12 (23.5%) | 4 (7.8%) | 8 (15.7%) | 5 (9.8%) |

| Simple cardiac malformation (n = 27) | 5 (18.5%) | 1 (3.7%) | 4 (14.8%) | 4 (14.8%) |

| Complex cardiac malformation (n = 24) | 7 (29.2%) | 3 (12.5%) | 4 (16.7%) | 1 (4.2%) |

| CHD with soft markers (n = 27) | 4 (14.8%) | 2 (7.4%) | 2 (7.4%) | 4 (14.8%) |

| CHD with structural anomalies (n = 17) | 6 (35.3%) | 1 (5.9%) | 5 (29.4%) | 1 (5.9%) |

| CHD with soft markers and structural anomalies (n = 7) | 2 (28.6%) | 1 (14.3%) | 1 (14.3%) | 0.000 |

| Simple cardiac malformation vs. Complex cardiac malformation | 0.573 | 0.333 | 1.000 | 0.353 |

| CHD with soft markers vs. CHD with structural anomalies | 0.162 | 1.000 | 0.129 | 0.673 |

| CHD with soft markers vs. CHD with soft markers and structural anomalies | 0.624 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.670 |

| CHD with structural anomalies vs. CHD with soft markers and structural anomalies | 0.664 | 1.000 | 0.795 | 1.000 |

The detection rate of chromosomal abnormalities in simple cardiac malformations

and complex cardiac malformations is listed in Table 1. The detection rate of

chromosomal abnormalities in complex cardiac malformations was 22.8%, which was

significantly higher than that in simple cardiac malformations (6.1%; p

Seven cases with negative CMA results were subjected to Trio-ES for simple cardiac malformations; thus, one P/LP variant and one VUS variant were detected. In the cases of complex cardiac malformations, 25 cases with negative CMA results underwent further Trio-ES; as a result, two P/LP variants and one VUS variant were identified. The overall diagnostic yield was 9.4%. The detailed genetic variants are shown in Table 4.

| Patient no. | Cardiac malformation | Extracardiac abnormality | Gene | Nucleotide change | Amino acid change | Zygosity | Clinical category | Inherited mode | Disease |

| 1 | LV/RV size disproportion, RVWT, TR | — | CSPP1 | NM_024790.6:c.1132C |

p.Arg378* | Hom | P | AR | Joubert syndrome 21 |

| 2 | VSD | CLP, pyelectasis | CEP290 | NM_025114.3:c.6604_6605insA | p.Ile2202Asnfs*4 | Hom | LP | AR | Bardet-Biedl syndrome 14; Joubert syndrome 5, Leber congenital amaurosis 10, Meckel syndrome 4, Senior-Loken syndrome 6 |

| 3 | LV/RV size disproportion, CA | FGR | SMARCA4 | NM_003072.3:c.520C |

p.Gln174* | Het | LP | AD | Autosomal dominant intellectual disability 16; Rhabdoid tumor predisposition syndrome 2 |

| 4 | DORV, VSD, PA, dextrocardia | — | NOTCH1 | NM_017617.3:c.173A |

p.Gln58Arg | Het | VUS | AD | Adams-Oliver syndrome 5; Aortic valve disease type 1 |

| 5 | VSD | Increased nuchal translucency | EPHB4 | NM_004444.4:c.778G |

p.Glu260Lys | Het | VUS | AD | Capillary malformation-arteriovenous malformation 2; Hydrops fetalis, nonimmune, and/or atrial septal defect |

AD, autosomal dominant; AR, autosomal recessive; LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular; RVWT, right ventricular wall thickening; TR, tricuspid regurgitation; CLP, cleft lip and palate; CA, coarctation of aorta; FGR, Fetal growth restriction; DORV, double outlet right ventricle; VSD, ventricular septal defect; PA, pulmonary stenosis; Hom, homozygous; Het, heterozygosity. The asterisks indicate a premature termination codon that leads to protein truncation.

CHD refers to a range of structural heart defects that develop during fetal growth and can substantially affect health outcomes. CHD includes various conditions, including simple anomalies (such as ASD and VSD) and complex malformations. These complex cases often involve multiple cardiac structures and may be associated with genetic syndromes or extracardiac anomalies [16]. Our study investigated the genetic findings in the prenatal diagnosis of CHDs and focused on the differences between simple and complex cardiac malformations.

Of the 211 fetuses diagnosed with CHD, 62.6% and 37.4% had simple and complex malformations, respectively. The proportion of different types of CHD was similar to that reported in relevant literature [17]. The overall rate of chromosomal abnormalities was 12.3%. Numerous studies have reported the detection rate of CMA in fetuses with CHD although rates vary depending on the array types used [18, 19]. The positive rate of prenatal CMA testing ranges from 6.6% to 38.7% [19, 20, 21]. In our study, the yield of the CMA test was generally consistent with previously published findings.

Our results indicated a significant distinction between the two groups; specifically, the rate of chromosomal abnormalities of complex CHD was markedly higher than that of simple CHD (22.8% vs. 6.1%). This finding was consistent with existing literature that suggests a stronger association between complex CHD and genetic factors, particularly in cases with structural anomalies and soft markers; therefore, these complex conditions likely exhibit a multifactorial etiology [18].

Our study revealed that the detection rates of chromosomal abnormalities significantly differed between isolated and non-isolated CHDs (8.7% vs. 23.5%). Previous studies reported similar findings in both groups of CHD [18, 22]. In isolated CHDs, the rate of chromosomal abnormalities in complex malformations was higher than that in simple malformations (20.0% vs. 2.9%). Furthermore, the presence of extracardiac anomalies or soft markers increased the likelihood of chromosomal abnormalities in simple and complex CHDs. Specifically, the detection rate in these cases increased to 23.5%. However, in non-isolated CHDs, the lack of a statistically significant difference suggested that extracardiac anomalies had a similar effect on genetic abnormalities in simple and complex CHDs. Therefore, non-cardiac anomalies may be important indicators for genetic testing regardless of the complexity of the heart defect [18, 23, 24, 25].

CMA is recommended as the first-line test. When CMA results are negative, ES is performed as a follow-up. However, the evidence supporting the use of ES in straightforward cases remains debated among experts. In our study, 32 fetuses with cardiac anomalies underwent ES when negative CMA results were obtained. The cohort comprised 7 cases of simple cardiac malformations and 25 cases of complex cardiac malformations. Among them, the proportion of fetuses with complex cardiac malformations was significantly higher; as such, ES evaluation was subsequently performed. Of the 7 cases with simple cardiac malformations in our study, 1 had a P/LP variant identified and only had one structural cardiac abnormality, which was VSD; however, it was combined with extracardiac abnormalities, which were cleft lip and palate and pyelectasis. Of the 25 cases with complex cardiac malformations in our study, 2 had P/LP variants identified, and 1 had multiple cardiac structural anomalies combined with fetal growth restriction (FGR). Our findings suggested that ES should be offered to the simple CHD group, particularly when extracardiac abnormalities are detected. Our diagnostic yield of 9.4% for ES was consistent with the established 10% yield reported in larger cohorts (n = 260) of fetuses with CHD [12]. This consistency remained despite our smaller sample size and was independent of CHD complexity or syndromic status. ES is necessary regardless of which cohort. Another study has also shown that approximately 10% of cases are attributable to de novo variants [26]. Therefore, ES should be offered to all pregnant women carrying a fetus with CHD that does not show chromosomal abnormalities or P/LP CNVs identified by CMA. This recommendation applies regardless of the classification of CHD.

A considerable limitation of this study was its relatively small sample size, especially the ES cases, which may limit the statistical power and generalizability of the findings. Larger prospective studies are warranted to validate our findings and obtain more precise estimates. The selection bias from patients retrospectively included with various degrees of cardiac and extracardiac anomalies could further distort the detection rates of chromosomal abnormalities. These issues highlighted the need for larger studies that not only include genetic testing but also involve clinical follow-up to evaluate the influence of genetic findings on patient management and outcomes. Furthermore, the retrospective nature of this study might hinder our ability to establish causal relationships between genetic factors and the complexity of cardiac malformations. Future research should address these limitations by incorporating comprehensive clinical data and investigating the functional implications of the identified genetic anomalies.

Our findings reveal notable differences in chromosomal abnormality detection rates between simple and complex cardiac malformations. Specifically, complex cases showed a stronger link to genetic anomalies. The higher prevalence of chromosomal abnormalities in CHD with extracardiac issues highlights the need for thorough genetic evaluation. Additionally, advanced genomic techniques such as ES should be integrated to further reveal genetic factors associated with all forms of CHD. Therefore, further research should clarify the complex relationship between genetic factors and structural heart abnormalities to improve prenatal diagnosis and management strategies.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

JG, PT, and SL designed the research study and manuscript writing. WZ performed data curation for the study. XW analyzed the data. All authors contributed to critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The research protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Jiaxing Maternity and Children Health Care Hospital (Ethics No. 2024-Y-87). Informed consent was waived for this retrospective study due to the exclusive use of de-identified patient data, which posed no potential harm or impact on patient care. The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance and instruction from all those who helped with the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research was funded by the project of Science and Technology Bureau of Jiaxing, Zhejiang Province (2022AD30093), the Medical and Health Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (2023KY1220), and the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LTGY24H040001).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this manuscript, the author(s) utilized DeepSeek-R1 exclusively for language polishing purposes. This tool assisted in improving grammatical accuracy, sentence structure, and overall readability of the text. The authors take full responsibility for the content integrity and have thoroughly reviewed and edited all AI-modified sections to ensure alignment with the original scientific intent.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.