1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Chongqing Emergency Medical Center, Chongqing University Central Hospital, 400014 Chongqing, China

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, The People’s Hospital of Yubei District of Chongqing, 401120 Chongqing, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Intrauterine infection poses significant risks to both mother and fetus, especially in cases of premature rupture of membranes (PROM). Early and accurate diagnosis is crucial for timely intervention.

This was a prospective study involving 120 patients with PROM, including 32 cases diagnosed with intrauterine infection and 88 non-infected controls. Parameters such as serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG), serum ferritin (SF), and gestational age (GA) were evaluated for their diagnostic efficacy using logistic regression and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis.

A total of 120 patients were analyzed, with 32 (26.67%) diagnosed with intrauterine infection. Infected patients exhibited significantly higher median β-hCG (43,104.00 vs. 22,375.00 mIU/mL; p < 0.0001) and SF (34.14 vs. 27.81 ng/mL; p = 0.0020), and a shorter mean gestational age (38.63 vs. 37.78 weeks; p = 0.0040). Furthermore, the logistic regression analysis established these as independent predictors, with significant ORs for log10-β-hCG (22.41; p = 0.0010), log10-SF (6.45; p = 0.0300), and gestational age (0.61; p = 0.0300). The combined testing approach, particularly the integration of log10-β-hCG, log10-SF, and GA, showed superior diagnostic efficacy, achieving an ROC area under the curve of 0.78, with significantly enhanced sensitivity and specificity.

The combined testing of serum β-hCG, SF, and GA offers a robust tool for the early diagnosis of intrauterine infection in women with PROM. These findings support the use of comprehensive biomarker screening in clinical settings to improve diagnostic accuracy and patient outcomes.

Keywords

- intrauterine infection

- premature rupture of membranes

- beta-human chorionic gonadotropin

- serum ferritin

- gestational age

Premature rupture of membranes (PROM) is a common obstetric complication during pregnancy. The earlier it occurs in gestation, the worse the prognosis for the perinatal infant, potentially leading to premature birth, oligohydramnios, placental abruption, umbilical cord prolapse, fetal distress, and neonatal respiratory distress syndrome. This condition significantly increases the rate of intrauterine infection and perinatal mortality for both the mother and fetus [1, 2]. Importantly, a spectrum of placental and amniotic fluid pathologies beyond PROM—including placenta accreta spectrum disorders, placental abruption, and amniotic fluid volume abnormalities have been similarly associated with adverse perinatal outcomes through shared pathophysiological mechanisms involving uteroplacental insufficiency and inflammatory cascade activation. These clinical parallels highlight the critical need for reliable biomarkers to predict and stratify infection-related pregnancy complications. It is generally believed that the main causes of PROM are infection, trauma, poor membrane development, cervical incompetence, and abnormal intrauterine pressure, which can lead to the destruction of the maternal membrane structure. As the gestational week progresses, the weaker parts of the membrane may rupture [3, 4, 5]. PROM and intrauterine infections are causally linked, with clinical studies confirming an extremely high risk of intrauterine infection among those with premature rupture, with infection rates exceeding 15% [5, 6]. This condition is also one of the main causes of poor maternal and infant outcomes.

Clinically, women with PROM often exhibit no obvious symptoms early on, such as fever, fetal tachycardia, or uterine tenderness, which complicates prenatal diagnosis. Laboratory tests and biomarkers are critical for early detection of intrauterine infection, including amniotic fluid culture, placental pathology, and the testing of serum procalcitonin (PCT), interleukin-6 (IL-6), and C-reactive protein (CRP) [5, 7]. However, traditional testing methods have limitations. For example, amniotic fluid cultures require several days, which may delay diagnosis. Some pathogens are anaerobic and difficult to culture, leading to a high rate of false negatives [8]. Pathological examinations are only available post-delivery and cannot predict early outcomes effectively. Serum markers like PCT, IL-6, and CRP are susceptible to stress and other interfering factors, making their results less stable [9, 10]. Thus, there is a need for a simple, reliable, non-invasive, and accurate method for early diagnosis of intrauterine infection in cases of PROM, warranting further clinical research.

Therefore, this study proposes to conduct a prospective analysis by enrolling pregnant women with PROM who meet the criteria, as well as healthy pregnant women. The study will measure levels of serum

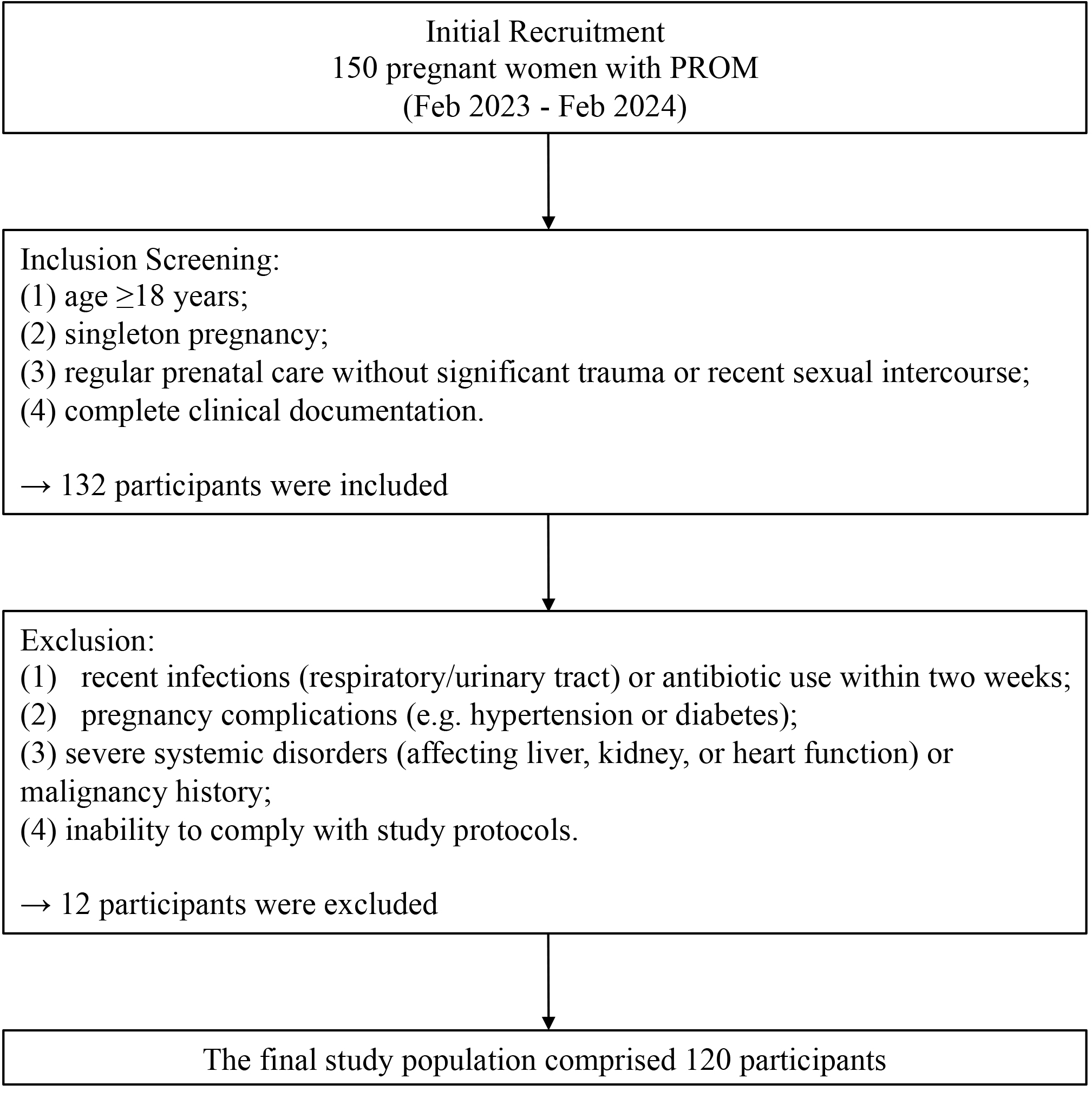

This prospective study enrolled 150 pregnant women diagnosed with PROM according to the 2015 Guidelines for Diagnosis and Management of PROM [18] from Chongqing University Central Hospital and the People’s Hospital of Yubei District between February 2023 and February 2024. Initial screening identified 132 eligible participants meeting all inclusion criteria: (1) age

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. The study flow chart. PROM, premature rupture of membranes.

Participants were stratified based on the degree of neutrophil infiltration in placental membrane tissues under high magnification into non-infection, mild infection, moderate infection, and severe infection categories. The Ethics Committee of Chongqing University Central Hospital approved the study protocol (2023-8). All participants were fully briefed on the study’s objectives and procedures, from which informed consent was voluntarily obtained.

Participant data collected included age, gestational age, length of hospital stay, parity, delivery mode, sex of the fetus, and newborn weight. On admission, 3 mL of venous blood was drawn, stored in dry vacuum coagulation tubes, and centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 15 minutes. The serum was then transferred to Eppendorf tubes and stored at –80 °C. Placental and membrane tissues were collected within 10 minutes post-delivery from near the rupture site for pathological analysis, fixed in formaldehyde, and processed with hematoxylin and eosin staining.

Serum

The placental membranes collected postpartum were fixed in formalin, processed into pathological sections, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin for microscopic examination. The severity was determined by examining placental membrane tissue slices for neutrophil infiltration per high-power field: none (

Participants were categorized into non-infected and infected groups, and then further subdivided by infection severity. Data are presented as mean

Spearman’s rank correlation analysis was conducted to evaluate the association between risk factors and intrauterine infection. Logistic regression analyses were performed to identify the risk factors for intrauterine infection. Two logistic regression models were developed: Model 1 adjusted for age, hospital stay, white blood cells (WBCs), neutrophils, and hemoglobin; Model 2 adjusted for gestational age and log-transformed serum levels. Multinomial logistic regression was used to assess the predictive value of serum markers and gestational age.

The C-statistics were calculated to measure the concordance between model-based risk estimates and intrauterine infection in PROM. Net reclassification improvement (NRI) and integrated discrimination improvement (IDI) were determined to measure the incremental prognostic effect of adding

The gold standard for diagnosis was pathological examination. The efficacy of combined serum

All statistical analyses were conducted by using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC, USA), or SPSS version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA), with significance set at a two-sided p-value of

The study included 120 patients with PROM, among whom 32 (26.67%) were diagnosed with intrauterine infection. The infected patients exhibited significantly higher median levels of serum

| Non-infected patients | Infected patients | p value* | |

| Number (%) | 88 (73.33) | 32 (26.67) | / |

| Age (years) | 28.97 | 28.81 | 0.8400 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 4.17 | 3.91 | 0.3300 |

| WBC count (×109/L) | 8.62 | 8.87 | 0.5300 |

| Neutrophil ratio (%) | 73.94 | 75.09 | 0.3200 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 122.51 | 119.36 | 0.1500 |

| Newborn weight (g) | 3188.00 | 3150.00 | 0.6200 |

| 22,375.00 (14,610.00, 38,357.00) | 43,104.00 (27,867.00, 65,027.00) | ||

| SF (ng/mL) | 27.81 (15.73, 42.72) | 34.14 (23.19, 72.79) | 0.0020 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 38.63 | 37.78 | 0.0040 |

Data are expressed as mean

| Non-infected patients | Mildly infected patients | Moderately infected patients | Severely infected patients | p value* | |

| Number, (%) | 88 (73.33) | 11 (9.17) | 9 (7.50) | 12 (10.00) | / |

| Age (years) | 28.97 | 29.45 | 27.11 | 29.50 | 0.5500 |

| Length of hospital stay (days) | 4.17 | 3.72 | 3.33 | 4.50 | 0.1500 |

| WBC count (×109/L) | 8.62 | 8.07 | 9.96 | 8.78 | 0.1500 |

| Neutrophils (%) | 73.94 | 74.79 | 75.43 | 75.11 | 0.7900 |

| Hemoglobin (g/L) | 122.51 | 119.30 | 119.91 | 118.99 | 0.5600 |

| Newborn weight (g) | 3188.00 | 3304.00 | 3060.00 | 3077.00 | 0.3800 |

| 22,375.00 (14,610.00, 38,357.00) | 31,333.00 (25,060.00, 45,892.00) | 43,258.00 (26,210.00, 74,641.00) | 45,070.00 (39,599.00, 71,859.00) | ||

| SF (ng/mL) | 27.81 (15.73, 42.72) | 22.98 (17.70, 48.10) | 26.67 (23.80, 45.22) | 61.78 (34.14, 84.97) | 0.0010 |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 38.62 | 38.49 | 37.52 | 37.34 | 0.0050 |

Data are expressed as mean

In the correlation analysis (Table 3), log10-

| Intrauterine infection | Intrauterine infection levels (non-, mildly, moderately, severely) | |||

| correlation coefficient | p value | correlation coefficient | p value | |

| Age | –0.01 | 0.8500 | –0.01 | 0.8500 |

| Length of hospital stay | –0.08 | 0.3200 | –0.06 | 0.4800 |

| WBC count | 0.04 | 0.6600 | 0.05 | 0.5300 |

| Neutrophile | 0.06 | 0.4800 | 0.06 | 0.4600 |

| Hemoglobin | –0.12 | 0.1700 | –0.11 | 0.1900 |

| Newborn weight | –0.03 | 0.7300 | –0.04 | 0.5900 |

| Log10- | 0.39 | 0.41 | ||

| Log10-SF | 0.23 | 0.0100 | 0.26 | 0.0030 |

| Gestational age | –0.26 | 0.0020 | –0.29 | 0.0010 |

For the logistic regression analysis (Table 4), elevated log10-

| Model 1 | p value | Model 2 | p value | ||

| Intrauterine infection | |||||

| Log10- | 31.42 (5.11, 193.23) | 0.0002 | 22.41 (3.39, 148.19) | 0.0010 | |

| Log10-SF | 13.45 (2.79, 64.72) | 0.0010 | 6.45 (1.10, 37.81) | 0.0300 | |

| Gestational age | 0.54 (0.36, 0.81) | 0.0020 | 0.61 (0.39, 0.97) | 0.0300 | |

| Intrauterine infection levels (non-, mildly, moderately, severely) | |||||

| Log10- | 16.88 (4.47, 63.53) | 13.56 (3.51, 52.92) | 0.0001 | ||

| Log10-SF | 10.74 (3.49, 33.05) | 5.47 (1.70, 17.52) | 0.0040 | ||

| Gestational age | 0.59 (0.43, 0.81) | 0.0010 | 0.71 (0.52, 0.97) | 0.0300 | |

Model 1 was adjusted for age, length of hospital stay, WBC, neutrophil number, hemoglobin, and newborn weight.

Model 2 was further adjusted for gestational weeks, log10-SF, and log10-

When analyzing infection severity (non-infected, mildly, moderately, severely), the risk increased significantly with higher log10-

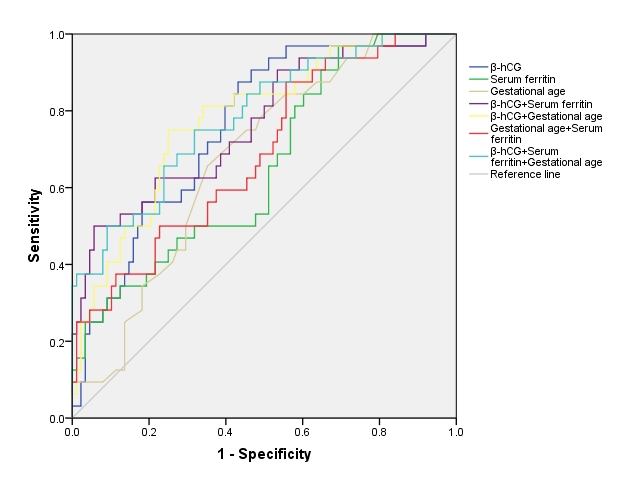

Fig. 2 presents the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, illustrating the diagnostic performance of these biomarkers. The combined approach using log10-

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2. The receiver operating characteristic analysis for the risk of intrauterine infection. This figure displays the ROC curve, plotted using sensitivity (true positive rate) against 1-specificity (false positive rate) based on the data from the predictive model. The AUC value included in the figure quantifies the model’s accuracy in distinguishing cases with and without the risk of intrauterine infection, reflecting its diagnostic ability. AUC, area under the curve; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

| Area under the curve (95% CIs) | p value | |

| 0.75 (0.66–0.85) | ||

| SF | 0.65 (0.55–0.76) | 0.0100 |

| Gestational age | 0.67 (0.57–0.77) | 0.0030 |

| 0.77 (0.67–0.86) | ||

| 0.78 (0.69–0.87) | ||

| SF + Gestational age | 0.69 (0.58–0.79) | 0.0020 |

| 0.78 (0.69–0.88) |

Abbreviation: 95% CIs, 95% confidence intervals.

Next, we compared the predictive performance of

| ∆C-statistics (95% CIs) | p values | IDI, % (95% CIs) | p values | NRI, % (95% CIs) | p value | |

| 0.17 (0.05, 0.28) | 0.0040 | 0.13 (0.06, 0.21) | 0.0001 | 0.61 (0.22, 1.00) | 0.0030 | |

| SF vs. risk factors | 0.12 (0.01, 0.23) | 0.020 | 0.10 (0.04, 0.17) | 0.0010 | 0.43 (0.04, 0.83) | 0.0300 |

| Gestational age vs. risk factors | 0.11 (0.01, 0.22) | 0.0300 | 0.07 (0.02, 0.13) | 0.0040 | 0.31 (–0.08, 0.71) | 0.1200 |

| 0.19 (0.07, 0.32) | 0.0010 | 0.22 (0.12, 0.31) | 0.59 (0.20, 0.97) | 0.0040 | ||

| 0.22 (0.11, 0.34) | 0.21 (0.12, 0.29) | 0.80 (0.43, 1.17) | ||||

| Gestational age + SF vs. risk factors | 0.16 (0.04, 0.27) | 0.0100 | 0.15 (0.07, 0.23) | 0.0003 | 0.29 (–0.10, 0.69) | 0.1500 |

| 0.22 (0.10, 0.33) | 0.0002 | 0.25 (0.15, 0.35) | 0.65 (0.27, 1.04) | 0.0010 |

Basic risk factors: age, length of hospital stay, WBC, neutrophil, hemoglobin, and newborn weight.

This study emphasizes the significant role of integrating SF,

The adoption of a multi-marker strategy in obstetric care, particularly for conditions like PROM, offers a more dynamic and sensitive approach to diagnosing intrauterine infections. Gestational age is a pivotal factor in maternal health, and its correlation with increased inflammatory responses at advanced stages can indicate higher risks of complications [20, 21]. The present study found that the shorter the gestational age, the higher the risk of intrauterine infection in patients with PROM. This finding aligns closely with previous studies [22, 23].

SF, recognized for its role as an acute-phase reactant, shows a strong correlation with the presence of intrauterine infection, supporting the findings of other studies that have used SF as a marker for systemic inflammation and infection in pregnant women [16, 21]. Ferritin is involved in iron metabolism, and during infection, it is synthesized in greater amounts to limit the availability of iron to pathogens, a process known as nutritional immunity [24]. Elevated SF levels provide a quantifiable measure that can be crucial in the early detection of subclinical infections.

Similarly, abnormal

Our findings support the literature advocating for the use of multiple diagnostic indicators to improve sensitivity and specificity in the detection of intrauterine infections [25, 26]. The use of a combined biomarker approach, yielding an AUC of 0.78, demonstrates a significant improvement over traditional single-marker methods and suggests potential changes in standard screening protocols for PROM.

Implementing a multi-marker strategy could lead to earlier and more accurate diagnoses, allowing healthcare providers to initiate appropriate and timely interventions. This proactive approach aligns with guidelines from major health organizations, including World Health Organization (WHO) and American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), which emphasize the need for precise and proactive management in cases of PROM to mitigate risks of infection and preterm labor [3, 25]. By integrating these biomarkers into routine prenatal care, we can potentially lower the incidence of adverse neonatal outcomes and improve maternal health.

This study has several limitations that should be acknowledged. Firstly, although participants were enrolled from two medical centers, the sample size remains relatively modest, which may limit the statistical power and the generalizability of the findings. Expanding the sample size in future studies could enhance the robustness of the conclusions. Secondly, while serum

In conclusion, the integration of gestational age, SF, and

The data that support the findings of this study are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants but are available from the corresponding author (YD) upon reasonable request.

YD designed the research study. YD and SY performed the research and analyzed the data. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was carried out in accordance with the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. We used a database started after ethical approval by the Ethics Committee of Chongqing University Central Hospital (2023-8), and all participants had provided written informed consent to have their data anonymously used in future research.

The authors thank the field workers for their contribution to the study and the participants for their cooperation. We also appreciate the reviewers’ insightful comments.

This research was funded by the Chongqing Science and Health Joint Medical Research Project (No. 2023QNXM019).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.