1 Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University, 430060 Wuhan, Hubei, China

2 Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Huashan Street Community Healthcare Center, 430076 Wuhan, Hubei, China

3 Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics, Qingshan District Maternal and Child Health Care Hospital, 430080 Wuhan, Hubei, China

Abstract

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is prevalent and significantly impacts morbidity. While some risk factors for SUI have been identified, those specifically related to the severity of SUI have not been thoroughly investigated.

This study recruited elderly female patients with SUI, aged over 60 years old, from Wuhan, Hubei, China, between October and November 2020. Data collection encompassed demographic information, clinical features (including obstetric history, chronic diseases, Urogenital Distress Inventory-6 (UDI-6), and International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form (ICIQ-SF) scores), as well as physical examinations (including assessments of pelvic floor muscle strength, pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) system, and pelvic floor ultrasound imaging).

Univariate analysis revealed that a history of postpartum urinary incontinence and chronic constipation significantly influenced the severity of SUI symptoms in the elderly (p < 0.05). Additionally, age, the number of vaginal deliveries, and a history of chronic cough were correlated with the severity of SUI symptoms, with p-values of 0.05, 0.08, and 0.12, respectively. Factors such as pelvic floor muscle strength, vaginal wall prolapse, uterine prolapse, and the morphology of the largest urethral opening all significantly impacted the severity of SUI symptoms in this population (p < 0.05). Multivariate logistic regression analysis identified age, the number of vaginal deliveries, chronic constipation, anterior vaginal wall prolapse, a history of postpartum urinary incontinence, and the shape of the maximum urethral opening as independent factors influencing SUI severity in older women (p < 0.05). The results of the Hosmer-Lemeshow test indicate that the model fits well (p = 0.37).

Age, the number of vaginal deliveries, anterior vaginal wall prolapse, a history of postpartum urinary incontinence, chronic constipation, and a funnel-shaped maximum urethral opening are associated with increased severity of SUI symptoms in elderly women. The severity of SUI escalates with advancing age and an increased number of vaginal deliveries.

Keywords

- stress urinary incontinence

- risk factors

- pelvic floor function

- elderly women

Stress urinary incontinence (SUI) is a prevalent condition among elderly women, characterized by involuntary urination following increased abdominal pressure while the detrusor muscle of the bladder remains relaxed. Epidemiological studies have shown that the overall incidence of SUI in Chinese women over 20 years old is 18.9%, and gradually increases with age, with up to 27.4% in the 60–69 years old age group [1]. In the United States, the incidence of urinary incontinence among women ranges from 38.0% to 49.2%, with SUI accounting for more than half of these cases and the annual cost of treating female urinary incontinence is estimated to reach $12 billion [2, 3]. The manifestation of SUI symptoms not only poses serious risks to women’s health and quality of life but also significantly contributes to the social burden associated with this condition.

Apart from age, previous studies have identified various factors related to SUI symptoms, such as body weight, mode of delivery, number of pregnancies, physical activity, and chronic diseases [4, 5, 6, 7, 8]. In clinical practice, the intervention strategies for SUI symptoms differ based on severity; mild SUI typically involves conservative measures like pelvic floor muscle exercises, whereas moderate to severe cases may necessitate physical therapy or surgical intervention. Currently, the factors influencing the severity of SUI symptoms remain inadequately defined, and as the population ages, middle-aged and elderly women—who are particularly susceptible to SUI—have garnered increasing social attention.

In this study, we collected data on demographics, obstetric history, chronic diseases, and scores from the Urogenital Distress Inventory-6 (UDI-6) and the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form (ICIQ-SF) [9, 10]. Through both univariate and multivariate analyses, we aimed to identify factors associated with the severity of SUI symptoms in the elderly, thereby enhancing the diagnosis and treatment of this condition.

A cross-sectional survey was conducted over a two-month period, from October to November 2020, among elderly female patients with SUI aged 60 years old and older in Wuhan, Hubei, China. The participants were drawn from the general community population. Face-to-face interviews and physical examinations were performed at the Qingshan District Maternal and Child Health Hospital and the Fozuling Community Health Service Center. This study received approval from the ethics committees of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University (approval number: WDRY2020-K198) and adheres to the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in Tokyo in 2008. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

This study included women over the age of 60 years old who exhibited symptoms of SUI, including both SUI and mixed urinary incontinence. The definitions provided by the International Continence Society (ICS) in 2002 were utilized for categorizing SUI and mixed urinary incontinence [11, 12]. The severity of SUI was assessed using the Ingelman-Sundberg grading system: Class I (mild) SUI symptoms occur only under intense stress, such as coughing, sneezing, or jogging; Class II (moderate) SUI symptoms arise under moderate stress, such as during vigorous exercise or while climbing stairs; and Class III (severe) SUI symptoms occur under mild pressure, such as standing, but can be managed when lying down [13].

In this study, we excluded cases exhibiting the following conditions:

① Severe pelvic organ prolapse (pelvic organ prolapse quantification stage III or IV).

② Cardiovascular disease or malignant tumors that pose a serious threat to life.

③ History of anti-SUI surgery.

④ Current lower urinary tract infections or a history of medication for lower urinary tract symptoms.

⑤ Inability to care for themselves or to complete the questionnaire.

⑥ Persistent unconscious urinary incontinence or chronic urinary retention.

This study involved the participation of 394 elderly female patients with SUI aged 60 years and older.

The study comprised several components: a questionnaire and physical examinations. The questionnaire collected data on demographic information, obstetric history, chronic diseases, and validated scales from the UDI-6 and ICIQ-SF. Demographic information included age, marital status, body mass index (BMI), and previous occupational status, which was categorized into several types: predominantly mental labor, predominantly light physical activities (e.g., typing and sewing, primarily involving the use of upper limbs), predominantly moderate physical activities (involving both upper and lower limb movements, such as driving, intermittent lifting, farming, and household chores), and predominantly heavy physical activities (entailing full-body exertion, such as lifting heavy objects and digging). Additional demographic factors included pelvic floor muscle exercise status, smoking status (active/passive), and years since menopause. Maternal history encompassed the number of births, the number of vaginal deliveries, history of vaginal midwifery, and postpartum urinary incontinence. Chronic diseases and other medical histories included a history of chronic cough, constipation, and hysterectomy. Data collection was conducted by obstetrics and gynecology interns. Gynecological examinations were performed using the modified Oxford grading system (for assessing pelvic floor muscle strength) [14, 15], pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) staging [16], cough stress tests [17], and Bonney tests [18], all conducted by qualified obstetricians and gynecologists. Transperineal ultrasound examinations, which assessed levator ani muscle injury and urethral opening size, were carried out by an ultrasound specialist utilizing the Color Doppler Diagnostic Ultrasound Logiq E9 (GE, Fairfield, CT, USA).

Kolmogorov-Smirnov normality test revealed that the UDI-6 and ICIQ-SF scores did not adhere to a normal distribution. Therefore, measurement data that deviated from normal distribution were presented as Median (Quartile), and comparisons between two groups were conducted using the Mann-Whitney U-test. Counting data were expressed as counts and percentage (%) and analyzed using the Chi-squared test. Univariate logistic regression analysis was utilized to identify factors associated with the severity of SUI. The odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence interval (CI) were employed to quantify the likelihood of the disease. A forward selection method was used for the multivariate logistic regression analysis to further assess the factors related to the severity of SUI. The significance level was set at p

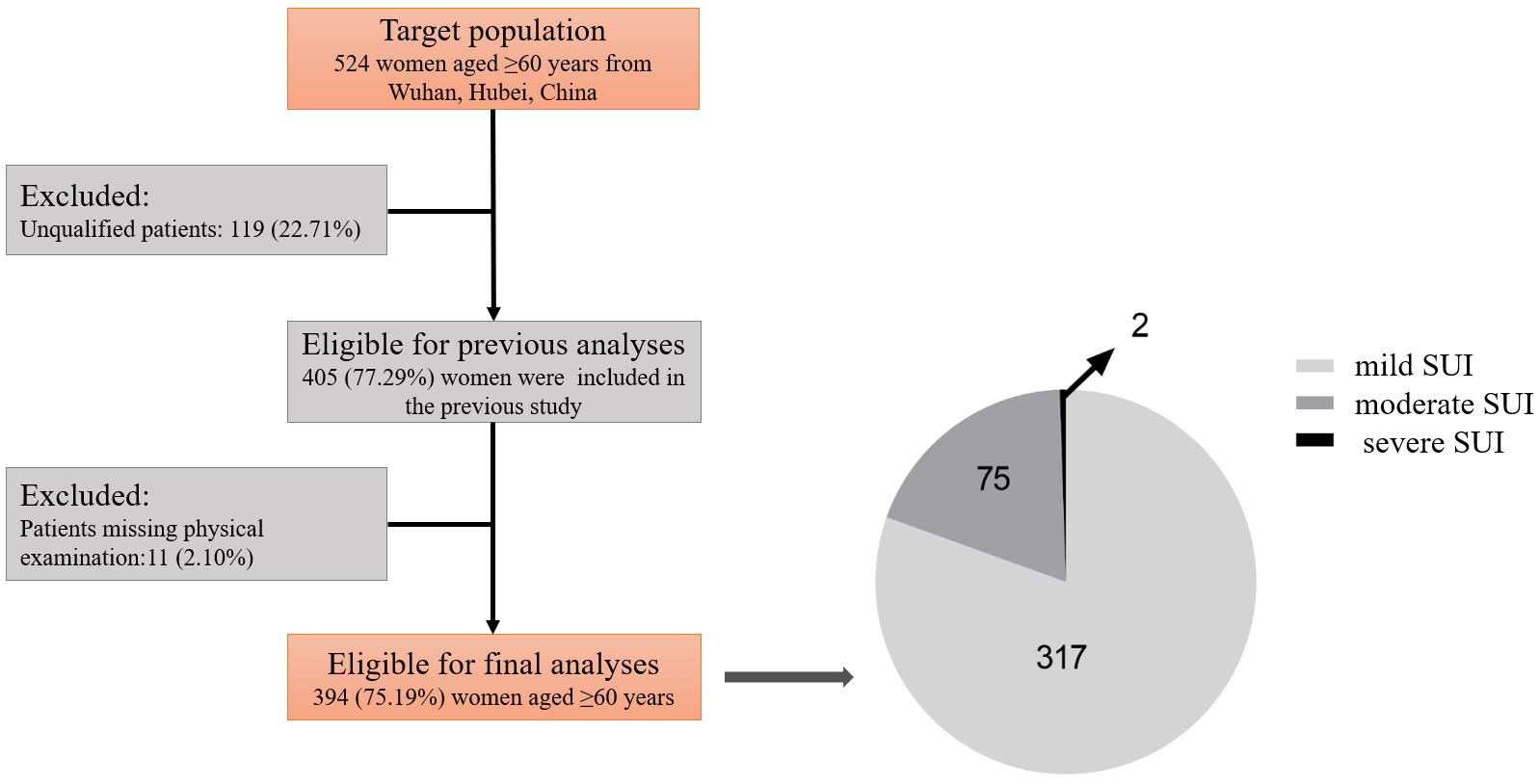

A total of 524 patients were recruited to participate in the study. After excluding 119 unqualified patients and 11 patients with incomplete physical examination information, a final cohort of 394 eligible elderly patients with SUI was included in the analysis. The workflow and distribution of patients with varying degrees of SUI symptoms are illustrated in Fig. 1. Among the participants, 317 exhibited mild SUI symptoms, representing 80.46% of the total; 75 had moderate SUI symptoms, accounting for 19.04%; and 2 patients presented with severe SUI symptoms, constituting 0.51%.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1. Study flowchart and distribution of patients with varying severity of SUI. SUI, stress urinary incontinence.

We compared the UDI-6 and ICIQ-SF scores between the mild SUI symptom group and the moderate to severe SUI symptom group, with the results presented in Table 1. The UDI-6 scores were 4.30

| Score | Mild (n = 317) | Moderate to severe (n = 77) | Z score | p-value |

| UDI-6 | 4 (2, 6) | 6 (4, 9.5) | –4.76 | |

| ICIQ-SF | 4 (3, 6) | 6 (4, 9.5) | –4.71 |

UDI-6, Urogenital Distress Inventory-6; ICIQ-SF, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire-Short Form.

The univariate analysis presented in Table 2 indicated that factors such as marital status, BMI, previous occupational status, history of pelvic floor muscle exercises, smoking and passive smoking history, and menopause status did not significantly influence the severity of SUI among the elderly, with no statistically significant differences observed (p

| Group | Mild (n = 317) [N (%)] | Moderate to severe (n = 77) [N (%)] | p-value | ||

| Age (years) | 5.82 | 0.05 | |||

| 60–65 | 154 (48.58%) | 26 (33.77%) | |||

| 65–70 | 87 (27.44%) | 25 (32.47%) | |||

| 76 (23.97%) | 26 (33.77%) | ||||

| Marital status | 2.08 | 0.15 | |||

| Married | 258 (81.39%) | 68 (88.31%) | |||

| Unmarried/divorced/widowed | 59 (18.61%) | 9 (11.69%) | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | 3.20 | 0.20 | |||

| 206 (64.98%) | 56 (72.73%) | ||||

| 25–30 | 97 (30.60%) | 16 (20.78%) | |||

| 14 (4.42%) | 5 (6.49%) | ||||

| Occupational status | 0.08 | 0.96 | |||

| Brainwork | 71 (22.40%) | 18 (23.38%) | |||

| Mild to moderate manual labor | 210 (66.25%) | 51 (66.23%) | |||

| Heavy manual labor | 36 (11.36%) | 8 (10.39%) | |||

| Pelvic floor muscle exercise history | 0.93 | 0.34 | |||

| Yes | 26 (8.20%) | 9 (11.69%) | |||

| No | 291 (91.80%) | 68 (88.31%) | |||

| Smoking and passive smoking history | 0.81 | 0.37 | |||

| Yes | 218 (68.77%) | 57 (74.03%) | |||

| No | 99 (31.23%) | 20 (25.97%) | |||

| Menopause history | 0.88 | 0.35 | |||

| 163 (51.42%) | 35 (45.45%) | ||||

| 154 (48.58%) | 42 (54.55%) | ||||

| Parity (times) | 4.19 | 0.12 | |||

| 0–1 | 132 (41.64%) | 42 (54.55%) | |||

| 2–3 | 137 (43.22%) | 26 (33.77%) | |||

| 48 (15.14%) | 9 (11.69%) | ||||

| Number of vaginal deliveries (times) | 5.11 | 0.08 | |||

| 0–1 | 128 (40.38%) | 42 (54.55%) | |||

| 2–3 | 148 (46.69%) | 28 (36.36%) | |||

| 41 (12.93%) | 7 (9.09%) | ||||

| History of vaginal midwifery | 1.75 | 0.19 | |||

| No | 230 (72.56%) | 50 (64.94%) | |||

| Yes | 87 (27.44%) | 27 (35.06%) | |||

| Postpartum urinary incontinence | 6.67 | 0.01 | |||

| No | 288 (90.85%) | 62 (80.52%) | |||

| Yes | 29 (9.15%) | 15 (19.48%) | |||

| History of chronic cough | 2.47 | 0.12 | |||

| No | 249 (78.55%) | 54 (70.13%) | |||

| Yes | 68 (21.45%) | 23 (29.87%) | |||

| Chronic constipation | 10.40 | ||||

| No | 192 (60.57%) | 31 (40.26%) | |||

| Yes | 125 (39.43%) | 46 (59.74%) | |||

| History of hysterectomy | 0.22 | 0.64 | |||

| No | 297 (93.70%) | 71 (92.21%) | |||

| Yes | 20 (6.31%) | 6 (7.79%) | |||

BMI, body mass index.

| Group | Mild (n = 317) [N (%)] | Moderate to severe (n = 77) [N (%)] | p-value | ||

| Modified Oxford grading system | 5.39 | 0.02 | |||

| Grade 0–2 | 96 (30.28%) | 34 (44.16%) | |||

| Grade 3–5 | 221 (69.72%) | 43 (55.84%) | |||

| Anterior vaginal wall prolapse | 11.62 | ||||

| No | 141 (44.48%) | 18 (23.38%) | |||

| I–II degree | 169 (53.31%) | 56 (72.73%) | |||

| III–IV degree | 7 (2.21%) | 3 (3.90%) | |||

| Uterine prolapse | 6.84 | 0.01 | |||

| No | 254 (80.13%) | 51 (66.23%) | |||

| Yes | 63 (19.87%) | 26 (33.77%) | |||

| Posterior vaginal wall prolapse | 7.11 | 0.01 | |||

| No | 248 (78.23%) | 49 (63.64%) | |||

| Yes | 69 (21.77%) | 28 (36.36%) | |||

| Funnel-shaped maximum urethral opening | 5.75 | 0.02 | |||

| Yes | 292 (92.11%) | 64 (83.12%) | |||

| No | 25 (7.89%) | 13 (16.88%) | |||

| Levator ani muscle injury | 1.19 | 0.28 | |||

| No | 313 (98.74%) | 74 (96.10%) | |||

| Yes | 4 (1.26%) | 3 (3.90%) | |||

Factors with a p-value

| Group | B-value | Standard error | Wald | p-value | OR (95% CI) | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 60–65 | 13.44 | |||||

| 65–70 | 0.67 | 0.34 | 3.98 | 0.05 | 1.95 (1.01, 3.76) | |

| 1.41 | 0.39 | 13.20 | 4.08 (1.91, 8.71) | |||

| Number of vaginal deliveries (times) | ||||||

| 0–1 | 8.45 | 0.02 | ||||

| 2–3 | –0.82 | 0.33 | 6.20 | 0.01 | 0.44 (0.23, 0.84) | |

| –1.22 | 0.52 | 5.49 | 0.02 | 0.29 (0.11, 0.82) | ||

| Anterior vaginal wall prolapse (degree) | ||||||

| No | 12.59 | |||||

| I–II | 1.09 | 0.31 | 12.07 | 2.98 (1.61, 5.50) | ||

| III–IV | 1.29 | 0.78 | 2.77 | 0.10 | 3.63 (0.80, 16.61) | |

| Postpartum urinary incontinence | ||||||

| No | ||||||

| Yes | 0.80 | 0.38 | 4.39 | 0.04 | 2.22 (1.05, 4.70) | |

| Chronic constipation | ||||||

| No | ||||||

| Yes | 0.73 | 0.28 | 7.01 | 2.08 (1.21, 3.57) | ||

| Funnel-shaped maximum urethral opening | ||||||

| No | ||||||

| Yes | 0.82 | 0.41 | 4.09 | 0.04 | 2.27 (1.03, 5.03) | |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Trauma to the pelvic floor nerves and supporting tissues—such as the urethral sphincter, vaginal wall, supporting ligaments, and pelvic floor muscles—resulting from pregnancy and vaginal delivery is a significant contributor to SUI. Two prominent theories currently recognized in the pathogenesis of SUI are the “Hammock Theory” and the “Pressure Conduction Theory”. The “Hammock Theory” first proposed by DeLancey in 1994 [19], posits that the urinary tract (including the bladder neck and urethra) is supported by the intrapelvic fascia and anterior vaginal wall, with stability maintained by the pelvic fascial tendon arch and levator ani muscle. When the “hammock” structure weakens, the urethral closing pressure becomes insufficient to ensure normal urinary control, leading to symptoms of urinary leakage [19]. The “Pressure Conduction Theory” introduced by Enhorning in 1961 [20], emphasizes the importance of structural integrity in the urethra and pelvic floor support for effective urinary control. Following an injury to the pelvic floor support, urethral resistance diminishes, and as the pelvic floor support tissues relax, the proximal urethra descends. Consequently, increased abdominal pressure fails to be transmitted to the urethral tissue, resulting in greater pressure being exerted on the bladder. Eventually, this causes the bladder pressure to exceed urethral pressure, leading to involuntary urine overflow [20]. Additionally, estrogen deficiency is recognized as another mechanism contributing to the onset of SUI symptoms. The incidence of SUI in elderly women is significantly higher than that in younger women [1]. Research has demonstrated that ovarian removal reduces the thickness of the vaginal wall muscle layer and diminishes vaginal contractility, which may play a role in the pathogenesis of SUI [21].

Based on research into the pathogenesis and etiology of SUI, the data analyzed in this study included age, marital status, BMI, previous occupational status, pelvic floor muscle exercise status, years since menopause, maternal history, and chronic diseases, which encompassed a history of chronic cough, constipation, and hysterectomy. Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that age, the number of vaginal deliveries, chronic constipation, anterior vaginal wall prolapse, a history of postpartum urinary incontinence, and the morphology of the maximum urethral opening significantly influence the severity of SUI symptoms in elderly individuals.

As individuals age, the elasticity and resilience of the pelvic floor tissues may decline, leading to a reduced ability to adapt to changes in intra-abdominal pressure, which in turn increases the risk of developing SUI and exacerbates its severity. Constipation can contribute to an increase in intra-abdominal pressure, and it is often associated with dysfunction of the pelvic floor muscles. Prolonged constipation may result in excessive tension or fatigue of these muscles, thereby impairing their support for the urethra and heightening the risk of SUI while worsening its symptoms. Constipation is closely related to factors such as age and gender, particularly in women, where the incidence of constipation tends to rise with age, correlating with an increased prevalence of SUI [22]. Previous study has indicated a significant association between constipation and SUI, suggesting that management of constipation should be considered in the treatment of SUI to improve the overall symptoms experienced by patients.

The anterior vaginal wall is closely associated with changes in bladder position; thus, the correlation between anterior vaginal wall prolapse and the severity of SUI symptoms in elderly women may stem from a decrease in proximal urethral pressure caused by the downward movement of urethral tissue, which alters the mechanical dynamics of the pelvic floor [23]. Furthermore, the occurrence of urinary incontinence after childbirth may be linked to pelvic floor tissue damage sustained during pregnancy and delivery, which can directly impact the future development of urinary incontinence in elderly women [24].

Transperineal ultrasound examination is a straightforward and effective method for assessing pelvic floor structures. It allows for dynamic observation of changes in the bladder, urethra, and vagina under varying abdominal pressures, enabling the determination of related parameters [25]. In this study, we measured several key indicators using transperineal ultrasound, including the thickness of the detrusor muscle, the length of the perineal body, the mobility of the bladder neck, the angle of rotation of the urethra, the angle of the posterior bladder, and the distance from the lowest point of the bladder to the posterior margin of the pubic symphysis. Notably, there were no significant differences in these indicators between the mild SUI group and the moderate-to-severe SUI group (data not shown). As abdominal pressure increases, the inner urethral orifice undergoes spatial shifts during rest and maximum Valsalva maneuvers. Recent clinical study has indicated that the maximum opening of the inner urethral orifice in SUI patients often assumes a funnel shape under increased abdominal pressure, and this funnel shape is closely linked to urinary leakage symptoms [26]. In our study, we found that the shape of the maximum opening of the urethra was significantly associated with the severity of SUI symptoms in elderly women. Specifically, a funnel-shaped maximum opening of the urethra correlated with the occurrence of moderate to severe SUI symptoms. These changes in the maximum opening of the urethra are related to the process of pelvic pressure conduction, suggesting that this parameter could serve as an effective indicator for guiding SUI therapy.

As a prevalent condition among elderly women, the treatment of SUI varies depending on the severity of the disease. Investigating the factors associated with SUI severity and further exploring its pathogenesis may enhance the diagnosis and treatment of this condition. This study was a cross-sectional analysis that included a total of 394 elderly patients presenting with SUI symptoms in Wuhan, Hubei Province, China. The findings revealed that several factors—namely age, number of vaginal deliveries, chronic constipation, anterior vaginal wall prolapse, history of postpartum urinary incontinence, and a funnel-shaped maximum opening of the urethra—were strongly associated with increased severity of SUI symptoms. But cross-sectional studies have notable limitations, including the inability to establish causality, potential selection bias affecting generalizability, reliance on self-reported data leading to measurement bias, and a static perspective that fails to capture changes over time in the relationships between variables. Future research should aim to include a larger cohort from diverse regions to provide a more comprehensive analysis. Additionally, the completion of prospective studies is anticipated to further elucidate the etiological factors linked to the severity of SUI symptoms, thereby offering valuable clinical guidance.

This study identified several independent factors that significantly influence the severity of SUI symptoms in the elderly, including age, constipation, number of vaginal deliveries, anterior vaginal wall prolapse, history of postpartum urinary incontinence, and the shape of the maximum opening of the urethra. The findings of this study provide new directions for the prevention and management of SUI. By addressing risk factors associated with severe SUI symptoms—such as improving constipation, strengthening pelvic floor muscle exercises postpartum, and timely addressing anatomical issues in the pelvic floor—treatment efficacy can be significantly enhanced, ultimately promoting the overall health and quality of life for elderly patients affected by this condition.

All data points generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article, and there are no additional underlying data required to reproduce the results.

SuL, LH designed the research study. SuL, ZW and LY performed the research. LJ and ShL provided help and advice on the data collection. SuL analyzed the data. LH: funding support, project supervision. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

All procedures involving human participants were conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the ethics committee of Renmin Hospital of Wuhan University (approval number: WDRY2020-K198) and adhered to the Declaration of Helsinki as revised in Tokyo in 2008. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all those who assisted us during the writing of this manuscript. We also extend our thanks to the peer reviewers for their valuable opinions and suggestions.

This study was funded by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Project Approval No.: 82401896) and the Hubei Key Research and Development Program (Project Approval No.: 2022BCA045).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.