1 Department of Nursing, Hangzhou Lin’an Traditional Chinese Medicine Hospital, Affiliated Hospital, Hangzhou City University, 311300 Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China

2 Department of Obstetrics, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, 530007 Nanning, Guangxi, China

3 Department of Nursing, The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, 530007 Nanning, Guangxi, China

Abstract

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is the most common metabolic disorder occurring during pregnancy. It affects 14.8% of pregnancies among Chinese women. Exercise can reduce insulin resistance and thus decrease the occurrence of adverse outcomes for women with GDM. This study aimed to examine the effects of three modes of exercise intervention on glycemic control, various pregnancy outcomes (including reduced incidence of preterm birth, gestational hypertension, and postpartum hemorrhage), and neonatal outcomes (such as lower birth weight and reduced incidence of neonatal complications like macrosomia and respiratory distress syndrome). Additionally, the study aim to identity the most effective exercise patterns for women with GDM.

A prospective cohort study was conducted to examine the effect of three exercise interventions — aerobic exercise (AE), resistance training (RT), and a combination of both (AE+RT) — on women with GDM. The primary outcomes measured were fasting blood glucose (FBG), 2-hour postprandial blood glucose (2h-PBG), and glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c). The secondary outcomes included maternal pregnancy outcomes and neonatal birth outcomes.

A total of 184 participants were included in this study, with 145 completing all follow-up assessments. Time exhibit a statistically significant effect on FBG (p < 0.001), whereas the different intervention methods did not present a significant effect on FBG (p = 0.32). Furthermore, time exhibited a statistically significant effect on 2h-PBG (p < 0.001). Following the interventions, all exercise groups exhibited significantly lower 2h-PBG levels compared to the control group (all p values < 0.05). The three exercise interventions demonstrated significantly different effects on improving the maternal outcome of postpartum hemorrhage (p = 0.01). The combined AE+RT group exhibited the lowest volume of postpartum hemorrhage (254.09, standard deviation (SD) = 103.57). Regarding neonatal outcomes, the macrosomia outcome has statistically significant differences (p = 0.04), and other outcomes found no significant differences between the three exercise intervention groups and the control group (all p values ≥ 0.05).

The combined AE+RT intervention demonstrated superior efficacy in reducing 2h-PBG, HbA1c levels, as well as postpartum bleeding, compared to the control group. Furthermore, a combination of AE+RT demonstrated greater efficacy in reducing 2h-PBG and HbA1c compared to single exercise groups. Therefore, combining AE+RT may be a more effective exercise regimen for managing of GDM in pregnant women.

The study has been registered on https://www.isrctn.com/ (registration number: ISRCTN40260907).

Keywords

- aerobic exercise

- resistance training

- gestational diabetes mellitus

- Chinese women

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is the most common metabolic disorder during pregnancy [1, 2]. GDM is defined as glucose intolerance of varying severity with onset during pregnancy [3, 4]. The global prevalence of GDM ranges from 6.6% to 45.3% [5, 6]. According to a systematic review and meta-analysis, GDM affects 14.8% of pregnancies among Chinese women [7]. Relevant risk factors for developing GDM include being overweight, having a family history of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), advanced maternal age, and physical inactivity [8].

Women with GDM may experience both short- and long-term complications [4, 9]. Short-term complications of GDM may include an increased risk of high blood pressure or preeclampsia, preterm delivery, induced labor, perineal trauma, and cesarean section delivery [9, 10]. GDM also increases the risk of the fetus being born large for gestational age and experiencing birth injury [9]. Regarding long-term complications, nearly half of women with GDM are at an increased risk of developing T2DM. Additionally, their children are more likely to develop metabolic syndrome during childhood and continue to experience it into early adulthood [10, 11].

First-line therapies for GDM include physical activity and dietary modifications [12]. Physical activity can reduce insulin resistance and thereby decrease the risk of adverse outcomes for women with GDM [13]. Previous research has reported that aerobic exercise (AE) and resistance training (RT) are commonly used interventions for managing GDM [14, 15, 16]. Regular AE and RT can increase muscle glucose uptake and improve the oxidative capacity of glucose in tissues. This improvement enhances insulin sensitivity and vascular function, lowers blood sugar levels, and reduces systemic inflammation [13, 17].

Although several reviews and recent trials have reported the benefits of AE or RT for GDM [14, 15, 16, 18, 19], no studies have explored the effects of combining of AE with RT (AE+RT) for women with GDM. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the effects of three different exercise interventions on glycemic control, pregnancy outcomes (including reduced incidence of preterm birth, gestational hypertension, and postpartum hemorrhage), and neonatal outcomes (such as lower birth weight and reduced incidence of neonatal complications like macrosomia and respiratory distress syndrome). Additionally, the study sought to identify the most effective exercise patterns for women with GDM.

This study hypothesized that exercise interventions — AE, RT, and a combination of both (AE+RT) — would significantly improve glycemic control, reduce the incidence of preterm birth, gestational hypertension, and postpartum hemorrhage, and improve neonatal outcomes in women with GDM compared to those who do not participate in structured exercise programs.

A prospective cohort study was conducted to examine the effects of exercise interventions on women with GDM from August 2019 to March 2021. As this study was not a randomized controlled trial (RCT), randomization was not conducted; however, the outcome assessor was blinded. Participants were allowed to self-select the group in which they wished to participate. An in-depth explanation of the counseling was provided to ensure they ensure they understood the group they were joining. By comparing groups with different exercise interventions, researchers can better identify the most effective intervention for improving outcomes. Additionally, including a control group helps to isolate the effects of each intervention by comparing them to participants who receive no intervention. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Medical and Health Research Ethics Committee of The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University (2020-KY-E-117). All participants provided informed consent before participating in the study. This study was registered under the registration number ISRCTN40260907.

The sample comprised pregnant women with GDM at 24–28 weeks of gestation. A

diagnosis of GDM is made using the one-step approach of a 75-g oral glucose

tolerance test. The diagnosis is confirmed if the plasma glucose values are

abnormal: fasting blood glucose (FBG)

The significance level (

The participants were assigned into four groups. The study intervention began at the participants’ gestational age of 24 weeks and concluded at 36 weeks. The frequency of intervention for all exercise groups was 3–4 times per week. All the exercise intervention groups were supervised by a midwife with certified fitness training, and wearable electronic bracelet were used to monitor the intensity of exercise.

(1) The AE group participated in a moderate-intensity walking intervention at a speed of 3–6 km/h or 100–200 steps/min. Exercise was recommended every other day. Participants were advised to start exercising 1 hour after a meal and continue for 40 minutes, with a family member present to ensure safety, provide motivation, and increase adherence to the exercise routine. (2) The RT group received an exercise intervention involving seated bicep curls with a 1-kg dumbbell. The routine targeted the major muscle groups and provided a general synopsis of the resistance exercises. This was performed every other day, 1 hour after a meal, for a duration of 40 minutes. (3) The combined AE+RT group performed a 20-minute moderate-intensity walk followed by seated bicep curls with a 1-kg dumbbell. This routine was performed once every other day, with the exercise session occurring 1 hour after a meal. The walking duration was 40 minutes, and the resistance training included five repetitions of each of the five different exercises, for a total of three sets. Participants were given a 15-second rest between each exercise and a 1-minute rest period between each set. (4) The control group received only routine prenatal care, personalized diabetes diet guidance, and online education guidance on weight control, blood glucose monitoring, and maintaining a food diary.

Outcome measures were based on previous similar research [22]. The primary outcome measures included FBG and 2-hour postprandial blood glucose (2h-PBG), both measured by Glucose Oxidase Method. Additionally, glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) was measured using High-Performance Liquid Chromatography. The secondary outcome measures included maternal pregnancy and neonatal birth outcomes, which were assessed using patients’ medical records. The pregnancy outcomes included: (1) maternal outcomes: gestational age, preterm birth, mode of delivery, gestational hypertension syndrome, insulin use, late pregnancy weight gain, postpartum hemorrhage; and (2) neonatal outcomes: birth weight, length at birth, 1-minute Apgar score, and incidence of neonatal complications such as respiratory distress syndrome. Data collection was conducted at baseline before the intervention, 1 and 3 months after the intervention, and 2 hours after delivery.

The data analysis was performed with SPSS version 25.0 software (IBM Corp.,

Armonk, NY, USA). Categorical and continuous variables are presented as n (%) or

mean

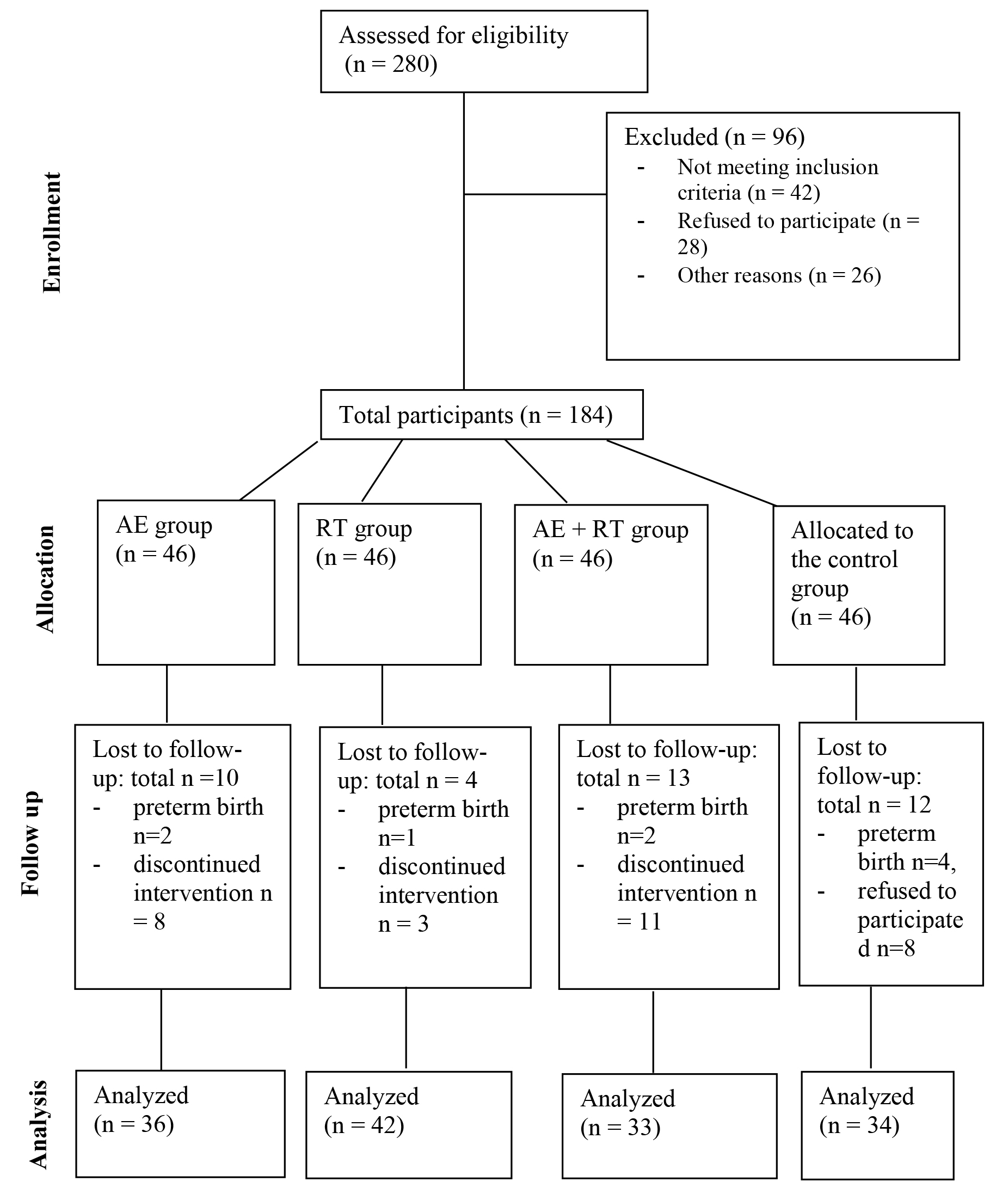

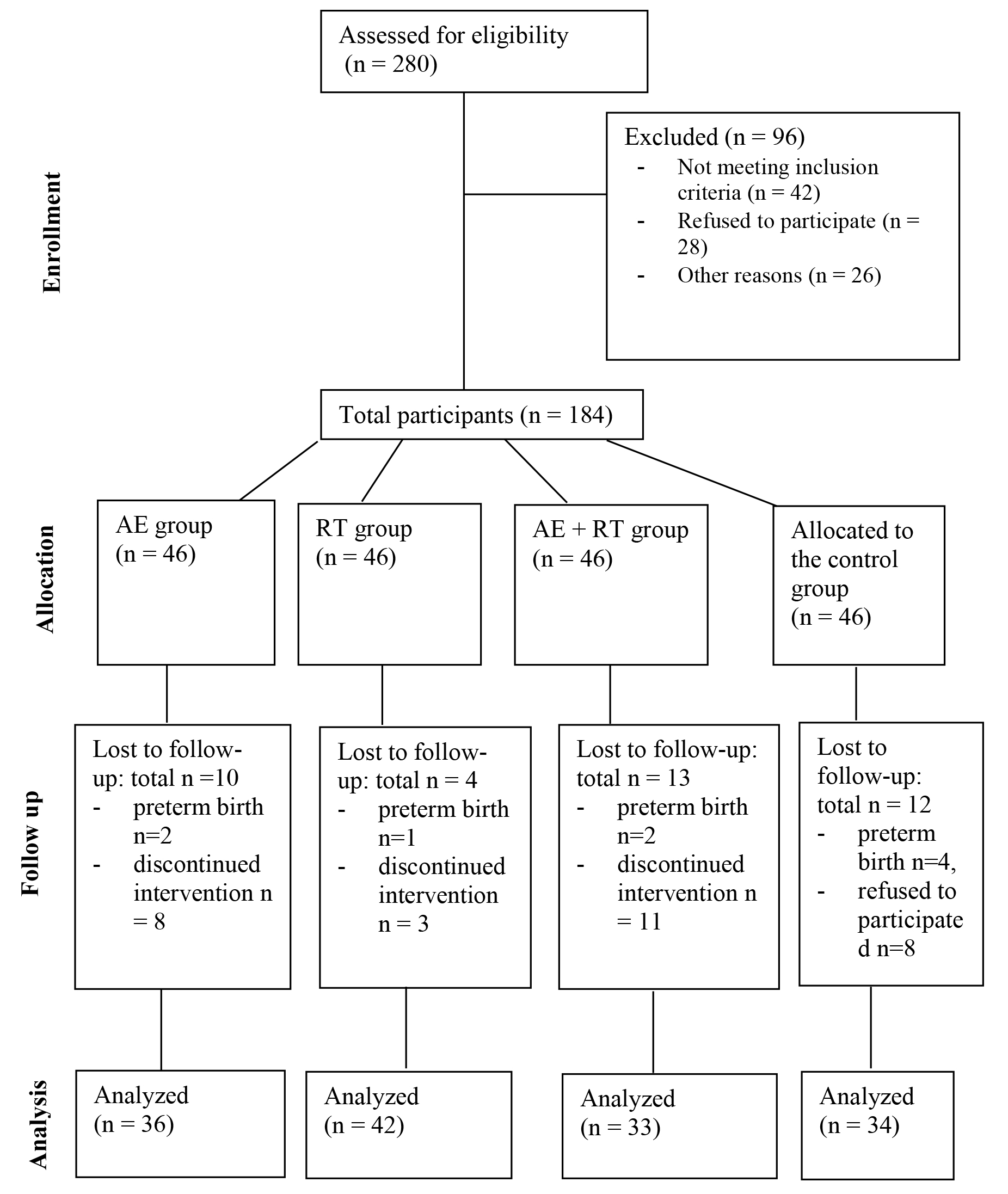

A total of 280 participants were screened, of which 184 were included in the study. Each group comprised 46 participants (Fig. 1). The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the participants at baseline are presented in Table 1. No significant differences were observed among the four groups in terms of age, gestational weeks, BMI, proportion of primiparous individuals, occupation, or education level.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study design diagram. AE, aerobic exercise; RT, resistance training.

| AE group | RT group | AE+RT group | Control group | F/χ2 | p-value | ||

| Age (years) | 30.14 (2.24) | 29.67 (2.75) | 30.21 (2.36) | 30.06 (2.08) | 0.40 | 0.75 | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 24.58 (0.55) | 24.64 (0.48) | 24.45 (0.56) | 24.44 (0.50) | 1.62 | 0.18 | |

| BMI (gestational age of 24 weeks) | 25.16 (3.07) | 25.47 (3.17) | 23.56 (2.95) | 23.99 (3.06) | 4.10 | 0.01 | |

| Primipara (%) | 23 (50.00) | 20 (43.48) | 32 (69.56) | 22 (47.83) | 7.39 | 0.06 | |

| Occupation | 6.62 | 0.68 | |||||

| Physical labor worker | 4 (8.69) | 3 (6.52) | 5 (10.87) | 6 (13.04) | |||

| Clerk | 30 (65.22) | 26 (56.52) | 24 (52.17) | 20 (43.48) | |||

| Self-employed | 4 (8.69) | 8 (17.39) | 7 (15.22) | 6 (13.04) | |||

| Others | 8 (17.39) | 9 (19.57) | 10 (21.74) | 14 (30.43) | |||

| Education | 7.68 | 0.57 | |||||

| Primary school | 5 (10.87) | 6 (13.04) | 5 (10.87) | 4 (8.69) | |||

| High school | 8 (17.39) | 12 (26.09) | 4 (8.69) | 9 (19.57) | |||

| College/university | 26 (56.52) | 25 (54.35) | 31 (67.39) | 25 (54.35) | |||

| Master or above | 7 (15.22) | 3 (6.52) | 6 (13.04) | 8 (17.39) | |||

Abbreviations: AE, aerobic exercise; BMI, body mass index; RT, resistance training.

Notes: data analysis at baseline were included all participants of 46 per group.

At baseline, no significant difference in FBG levels was observed (p =

0.38). Repeated-measures ANOVA indicated no significant interaction between

different intervention times and methods (p = 0.87). Time had a

significant main effect on FBG (p

| Time point | AE group | RT group | AE+RT group | Control group |

| Baseline | 4.56 (0.35) | 4.64 (0.37) | 4.60 (0.62) | 4.74 (0.48) |

| 1-month after intervention | 4.40 (0.31) | 4.35 (0.31) | 4.28 (0.53) | 4.43 (0.38) |

| 3-month after intervention | 4.24 (0.39) | 4.22 (0.37) | 4.19 (0.46) | 4.26 (0.42) |

| F | Finteraction = 0.42 | Ftime = 39.12 | Fbetween group = 1.19 | Fbaseline = 1.04 |

| p-value | p𝑖𝑛𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑎𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 = 0.87 | p𝑡𝑖𝑚𝑒 |

pbetween group = 0.32 | p𝑏𝑎𝑠𝑒𝑙𝑖𝑛𝑒 = 0.38 |

Abbreviations: AE, aerobic exercise; RT, resistance training; FBG, fasting blood glucose.

Notes: the total number of participants among each group at baseline was 46, and the total number of participants at 1-month and 3-month after intervention was 36 for AE group, 42 for RT group, 33 for AE+RT group, and 34 for the control group.

At baseline, no significant difference was observed in 2h-PBG levels (p

= 0.72). Repeated-measures ANOVA indicated no significant interaction between

different intervention times and methods (p = 0.10). Time had a

significant main effect on 2h-PBG levels (p

| Time point | AE group | RT group | AE+RT group | Control group |

| Baseline | 9.27 (0.97) | 9.38 (1.18) | 9.12 (1.48) | 9.12 (0.92) |

| 1-month after intervention | 5.98 (0.81) | 5.84 (0.66) | 5.56 (1.11) | 6.28 (0.39) |

| 3-month after intervention | 5.91 (0.72) | 5.78 (0.55) | 5.37 (0.58) | 6.21 (0.90) |

| F | Finteraction = 1.85 | Ftime = 698.34 | Fbetween group = 5.33 | Fbaseline = 0.45 |

| p-value | p𝑖𝑛𝑡𝑒𝑟𝑎𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛 = 0.10 | p𝑡𝑖𝑚𝑒 |

pbetween group = 0.002 | p𝑏𝑎𝑠𝑒𝑙𝑖𝑛𝑒 = 0.72 |

Abbreviations: AE, aerobic exercise; RT, resistance training; 2h-PBG, 2-hour postprandial blood glucose.

Notes: the total number of participants among each group at baseline was 46, and the total number of participants at 1-month and 3-month after intervention was 36 for AE group, 42 for RT group, 33 for AE+RT group, and 34 for the control group.

| (I) group | (J) group | Mean difference (I–J) | p-value |

| Control | AE | 0.50 | 0.010 |

| RT | 0.37 | 0.020 | |

| AE+RT | 0.74 | ||

| AE | Control | –0.50 | 0.010 |

| RT | –0.13 | 0.730 | |

| AE+RT | 0.23 | 0.270 | |

| RT | Control | –0.37 | 0.020 |

| AE | 0.13 | 0.730 | |

| AE+RT | 0.36 | 0.030 | |

| AE+RT | Control | –0.74 | |

| AE | –0.23 | 0.270 | |

| RT | –0.36 | 0.030 |

Abbreviations: AE, aerobic exercise; RT, resistance training; 2h-PBG, 2-hour postprandial blood glucose.

As shown in Table 3b, all three exercise intervention groups had significantly

different 2h-PBG levels compared to the control group (all p values

As shown in Table 4a, no significant difference in HbA1c levels was observed at

baseline. However, a significant difference was detected at 3 months after the

intervention (p

| Time point | AE group | RT group | AE+RT group | Control group | F | p-value |

| Baseline | 5.63 (0.44) | 5.76 (0.41) | 5.70 (0.24) | 5.70 (0.36) | 0.63 | 0.590 |

| 3-month after intervention | 5.52 (0.43) | 5.50 (0.22) | 5.34 (0.33) | 5.70 (0.26) | 8.20 |

Abbreviations: AE, aerobic exercise; RT, resistance training; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin A1c.

Note: HbA1c measures average blood glucose levels; therefore, this study only assessed at the end of 3-month after intervention. The total number of participants among each group at baseline was 46, and the total number of participants at 1-month and 3-month after intervention was 36 for AE group, 42 for RT group, 33 for AE+RT group, and 34 for the control group.

| (I) group | (J) group | Mean Difference (I–J) | p-value |

| Control | AE | 0.21 | 0.010 |

| RT | 0.20 | 0.020 | |

| AE+RT | 0.38 | ||

| AE | Control | –0.21 | 0.010 |

| RT | –0.01 | 0.990 | |

| AE+RT | 0.17 | 0.020 | |

| RT | Control | –0.20 | 0.010 |

| AE | 0.01 | 0.990 | |

| AE+RT | 0.18 | 0.010 | |

| AE+RT | Control | –0.38 | |

| AE | –0.17 | 0.020 | |

| RT | –0.18 | 0.010 |

Abbreviations: AE, aerobic exercise; RT, resistance training; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin A1c.

As shown in Table 4b, the three exercise intervention groups had significantly

different HbA1c levels compared to the control group (all p values

As shown in Table 5, the exercise interventions significantly differed in their

effect on postpartum hemorrhage (p = 0.01), with the combined AE+RT

group resulting in the lowest volume of postpartum hemorrhage. However, no

significant differences were observed for other maternal outcomes (all

p-values

| AE group | RT group | AE+RT group | Control group | F/χ2 | p-values | |

| Gestational age (weeks) | 38.31 (1.92) | 38.24 (1.62) | 38.82 (1.10) | 38.65 (0.81) | 1.42 | 0.24 |

| Preterm birth, n (%) | 2 (5.56) | 4 (9.52) | 3 (9.10) | 0 (0.00) | 3.54 | 0.32 |

| Cesarean section delivery, n (%) | 13 (36.11) | 11 (26.19) | 9 (27.27) | 17 (50.00) | 5.70 | 0.13 |

| Gestational hypertension, n (%) | 2 (5.56) | 5 (11.90) | 0 (0.00) | 5 (14.71) | 5.91 | 0.12 |

| Polyhydramnios, n (%) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 2 (5.89) | 6.62 | 0.09 |

| Insulin use, n (%) | 3 (8.33) | 3 (7.14) | 1 (3.03) | 1 (2.94) | 1.59 | 0.66 |

| Postpartum hemorrhage (mL) | 276.16 (129.14) | 260.35 (113.97) | 254.09 (103.57) | 345.94 (131.73) | 4.29 | 0.01 |

Abbreviations: AE, aerobic exercise; RT, resistance training.

Notes: the total number of participants among each group at baseline was 46, and the total number of participants at 1-month and 3-month after intervention was 36 for AE group, 42 for RT group, 33 for AE+RT group, and 34 for the control group.

As shown in Table 6, there were no significant differences in neonatal outcomes,

including birth weight, length at birth, 1-minute Apgar score, neonatal hypoglycemia,

or respiratory distress syndrome. The macrosomia outcome

has statistically significant differences (p = 0.04), and other outcomes found no

significant differences between the three exercise intervention groups and the

control group (all p values

| AE group | RT group | AE+RT group | Control group | F/χ2 | p-values | |

| Birth weight (g) | 3140.75 (556.97) | 3242.38 (513.80) | 3257.73 (471.45) | 3332.06 (453.53) | 0.86 | 0.46 |

| Length at birth (cm) | 50.72 (2.68) | 50.81 (2.44) | 50.69 (1.68) | 50.88 (1.27) | 0.10 | 0.96 |

| 1-minute Apgar score | 9.81 (0.66) | 9.95 (0.21) | 9.94 (0.24) | 9.91 (0.37) | 0.58 | 0.63 |

| Macrosomia, n (%) | 1 (2.78) | 1 (2.38) | 2 (6.06) | 6 (17.65) | 8.44 | 0.04 |

| Hypoglycemia, n (%) | 2 (5.56) | 1 (2.38) | 1 (3.03) | 4 (11.76) | 3.73 | 0.29 |

| Respiratory distress syndrome, n (%) | 3 (8.33) | 2 (4.76) | 0 (0.00) | 0 (0.00) | 5.19 | 0.16 |

Abbreviations: AE, aerobic exercise; RT, resistance training.

Notes: the total number of participants among each group at baseline was 46, and the total number of participants at 1-month and 3-month after intervention was 36 for AE group, 42 for RT group, 33 for AE+RT group, and 34 for the control group.

This study aimed to examine the effects of various exercise interventions on pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. AE alone, RT alone, and combined AE+RT had significant effects in reducing FBG, 2h-PBG, and HbA1c levels compared to the control group, which did not receive any exercise intervention. Among these three exercise interventions, combined AE+RT had a more significant effect on glycemic control compared to AE or RT alone. This finding is consistent with previous research in pregnant populations [23].

The potential mechanism by which exercise interventions reduce blood glucose levels may involve increased insulin sensitivity [24, 25]. The pathways through which exercise increases insulin sensitivity include elevated concentrations of glucose transporter proteins in skeletal muscle, changes in muscle fiber types, and increased glycogen synthase activity. Studies have found that long-term AE can increase capillary density, improving the efficiency of glucose delivery to muscles and enhancing insulin activity to boost muscle glucose uptake [23, 24, 25]. RT can enhance muscle capillary networks, increase muscle volume, reduce body fat, actively stimulate signaling pathways, lower inflammation levels, improve antioxidant capacity, and increase adiponectin levels. These effects contribute to enhancement of the adiponectin pathway, which helps to effectively improve blood glucose levels [23, 24]. Combined AE+RT leverages different physiological mechanisms by activating both metabolic pathways, potentially offering greater physiological benefits than using either approach alone [23, 25].

Existing studies comparing different exercise methods for patients with T2DM have similarly shown that the combined AE+RT results in better glycemic control compared to other exercise approaches [26, 27]. One study conducted a 26-week exercise study on adult patients with T2DM and found that combined AE+RT led to the greatest improvement in blood glucose control compared to the groups receiving AE or RT alone [26]. Xu et al. [27] also reported that among elderly patients with T2DM undergoing 24 weeks of combined AE+RT, blood glucose levels were better controlled compared to those undergoing only AE or RT alone. Given that the combination of AE and RT shows superior glycemic control in both pregnant women with GDM and adult patients with T2DM, this combined intervention should be recommended for pregnant women with GDM.

Postpartum hemorrhage is a common complication following childbirth and is a leading cause of maternal mortality. This study found that women with GDM in the three exercise intervention groups experienced lower postpartum bleeding volumes compared to the control group. In particular, the combined AE+RT group had the lowest postpartum bleeding volume, which is consistent with previous research by Zhong et al. [23]. Regarding neonatal outcomes, this study found no statistically significant differences among the three exercise intervention groups compared with the control group. However, a higher occurrence of macrosomia was observed in the control group. Recent research suggests that glycemic variability may significantly influence the relationship between GDM and excessive neonatal birth weight, indicating that improved glycemic control can effectively reduce the risk of macrosomia [28].

Overall, this study’s strengths include the implementation of multiple exercise interventions and the demonstration of positive effects on both maternal and neonatal outcomes. (1) The study examined the effects of comprehensive interventions of AE, RT, and their combined effect on glycemic control, pregnancy, and neonatal outcomes, providing insights into the most effective exercise regimen for managing GDM. (2) The study demonstrated that the combined exercise intervention not only improved glycemic control but also significantly reduced postpartum hemorrhage volume, highlighting that the combined AE+RT intervention could be considered as the most effective management strategy for GDM.

This study has several limitations. (1) It focused exclusively on the effects of exercise in pregnant women with GDM and did not include pregnant women with type 1 or 2 diabetes. (2) The study did not include postpartum follow-up assessments to evaluate the risk of diabetes in participants or the risk of diabetes and other diseases in their offspring. Future research should focus on long-term follow-up to assess the sustained effects of exercise interventions on both maternal and infant health. (3) The study monitored the effects of exercise interventions on glycemic control using traditional methods administered by healthcare providers. With advancements in digital technologies, future research should utilize fitness trackers and smartwatches to monitor the blood glucose control in women with GDM [15]. (4) This study did not collect detailed information on medication use for all participants.

The combined AE+RT intervention was more effective than the control group in reducing FBG, 2h-PBG, HbA1c levels, and postpartum bleeding. Additionally, of the combined AE+RT intervention demonstrated greater effect on 2h-PBG and HbA1c levels than single exercise groups. Therefore, combined AE+RT interventions may be a more effective for managing GDM in pregnant women.

Data is available upon request. Please contact Dr. Yingchun Zeng by chloezengyc@qq.com.

YZ, XW, XD, QH designed this study. YZ drafted the main manuscript. YZ, XM, MW, and YQ collected data and ran the statistical analyses. All authors provided edits and feedback on the manuscript. QH secured funding and were responsible for study design. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

This study was approved by The Second Affiliated Hospital of Guangxi Medical University, approved number 2020-KY-E-117. All participants were consented for this research study and provided written consent form. All research was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research was supported by the following research projects: Joint Project on Regional High-Incidence Diseases Research of Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (#2023GXNSFAA026241); Guangxi Medical and Health Appropriate Technology Development and Application Project (#S2022095); Guangxi Medical and Health Appropriate Technology Development and Application Project (#S2019101).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

During the preparation of this work the authors used ChatGpt-3.5 in order to check spell and grammar. After using this tool, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the publication.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.