1 Department of Nursing, The Affiliated Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital of Qingdao University, 264000 Yantai, Shandong, China

2 Department of Internal Medicine, The Affiliated Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital of Qingdao University, 264000 Yantai, Shandong, China

3 Department of Clinical Nutrition, The Affiliated Yantai Yuhuangding Hospital of Qingdao University, 264000 Yantai, Shandong, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

The association between vitamin D and pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) remains contentious. The aim of our study was to evaluate the existence of an association between serum vitamin D levels and the incidence of PIH.

We conducted a literature search in PubMed, the Cochrane Library, and Embase databases in June 2024 using the following search terms: 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D), Vitamin D, 1,25(OH)2D, VD, 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D or 25(OH)D, combined with PIH. Two reviewers independently screened the literature based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. Data were then extracted and assessed for quality. Comparisons were made between the highest and lowest categories of serum vitamin D levels. Relative risks (RRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), adjusted for multivariable effects, were pooled using a random-effects model. A two-stage dose-response meta-analysis was used to evaluate the trends.

17 studies met the inclusion criteria. Of these, 11 prospective studies investigated the relationship between vitamin D levels and gestational hypertension, involving 8834 events and 17,104 participants. The results showed that vitamin D was only marginally associated with hypertensive disorders in pregnancy (summary RR = 0.99; 95% CI: 0.97–1.02; I2 = 67.5%; p = 0.001). However, 6 case-control studies investigated the relationship between vitamin D levels and gestational hypertension, involving 80,814 events and 330,254 participants. The results showed that vitamin D is not associated with pregnancy hypertensive disorders (summary RR = 1.09; 95% CI: 0.84–1.41; I2 = 75.4%; p = 0.001). In the subgroup analysis, the pooled effect of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) showed a slight association with gestational hypertension (pooled RR = 0.99; 95% CI: 0.96–1.02; I2 = 72.6%; p = 0.000). The dose-response analysis showed that increasing vitamin D doses are marginally associated with a decrease in the incidence rate.

Our research suggests that the risk of PIH may not be related to the vitamin D levels. Our research supports the hypothesis that gestational hypertension may not be associated with low levels of vitamin D, indicating that the role of vitamin D may not be significant.

Keywords

- pregnancy-induced hypertension

- vitamin D

- meta-analysis

Pregnancy-induced hypertension (PIH) complicates up to 10% of pregnancies worldwide and is a major contributor to morbidity and mortality among both mothers and newborns [1, 2, 3]. Vitamin D deficiency is prevalent during pregnancy, with a prevalence of 8–70% [4]. Vitamin D, a key micronutrient known for its role in regulating calcium balance and maintaining bone health, is essential during pregnancy. Vitamin D in the diet comes in two forms: vitamin D2 and vitamin D3. Both forms are converted to 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25(OH)D) in the liver [5, 6]. 25(OH)D is converted to 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, the major bioactive form of vitamin D, in response to the regulation of serum calcium and phosphorus levels and parathyroid hormone [7]. Vitamin D plays a significant role in modulating inflammation and regulating immune function [8].

Extensive research has been conducted on the role of vitamin D in pregnancy and its impact on various other health outcomes. PIH can lead to a high incidence of severe maternal and infant complications, as well as increased mortality rates. Extensive research has associated vitamin D to PIH. On one hand, vitamin D may repair the damage to the trophoblast and support angiogenesis and endothelial repair [9, 10]. On the other hand, vitamin D may reduce the incidence of PIH by regulating normal placental calcium transport and immune regulatory function [11, 12].

However, evidence regarding the effectiveness of vitamin D supplementation in preventing PIH is conflicting [13, 14, 15]. Considering the widespread prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and the inconsistent evidence linking vitamin D and PIH disorders, this study was conducted to provide a comprehensive and up-to-date evaluation of the relationship between vitamin D and PIH.

A systematic search of the literature was conducted in PubMed, Cochrane Library, and Embase databases up to June 2024, using the following search terms: “1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D”, “vitamin D”, “25-hydroxyvitamin D”, “VD”, “25(OH)D OR 1,25(OH)2D”, combined with “perinatal” or “pregnancy”, and “high blood pressure” or “hypertension” or “preeclampsia”. The PICOS criteria: participant/patients: pregnant woman; intervention: vitamin D supplementation; comparison: blank control; outcome: PIH syndrome; study design: cohort studies, case-control studies, cross sectional studies, and experimental research methods.

Potential studies were identified through independent searches of titles, abstracts, and full texts by two authors. The inclusion criteria focused on selecting studies that examined the association between vitamin D levels and the incidence of the rate of preeclampsia or PIH. The exclusion criteria included reviews, case reports, and study protocols, which were not eligible for inclusion. The inclusion criteria were limited to prospective cohort studies and nested case-control studies. The exposure of interest was the concentration of 25(OH)D in serum or plasma, with the number of patients developing PIH during follow-up serving as the endpoint of interest. We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist to complete the meta-analysis.

Data were extracted and analyzed by two investigators. The following characteristics were extracted from the eligible studies that were eligible for inclusion: relative risk (RR), the 25(OH)D assay method, and the 95% confidence interval (CI). In this type of study, the group receiving the lowest dose of vitamin D served was used as the reference group [16]. To assess quality, we used the Newcastle-Ottawa scale, which has a maximum score of 9 stars. Studies were classified as low, medium, or high quality based on scores of 0–3, 4–6 and 7–9 stars, respectively [17]. The assessments were carried out by two assessors, with any disagreements resolved through consultation with a third assessor.

The statistical analyses were performed using STATA 11.0 (STATA Corp., College station, TX, USA). The two-tailed p value was calculated, with the level of significance set at 0.05.

For the association between vitamin D and PIH, the RR was considered a general risk estimate. For the purpose of synthesizing the data, the odds ratio (OR) or hazard ratio (HR) was used as a direct estimate of the RR. To estimate the potential curvilinear relationship, a dose-response meta-analysis using random effects was performed. To estimate the association between vitamin D and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, a two-stage random-effects dose-response analysis was used [18]. The p-value for non-linearity is calculated by testing the null hypothesis that all regression coefficients of the spline transformation are equal to zero [19].

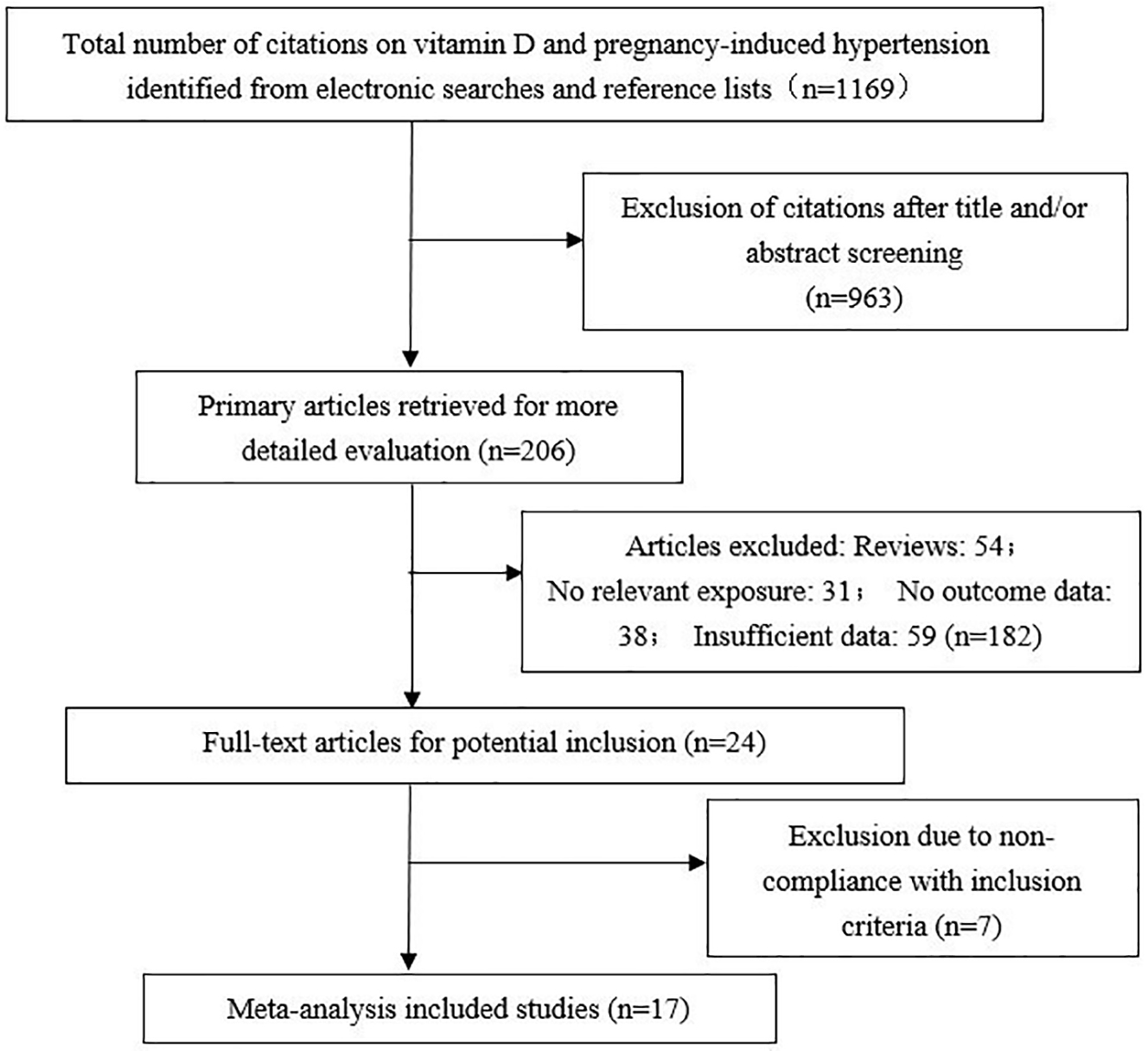

The method used to search and select the studies is shown in Fig. 1. A total of 17 trials were analyzed, encompassing 347,358 participants [11, 14, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]. After removing duplicates had been removed, 963 citations were excluded based on title and abstract screening, leaving 206 articles for further review. Among them, 182 articles were excluded dur to being reviews, lacking relevant exposure data, having no outcome data, or providing insufficient data. 7 studies were excluded because they lacked a suitable controlled design for vitamin D supplementation or had other factors that could interfere with the research results. Ultimately, 17 articles were selected. The characteristics of the included studies are detailed in Table 1 (Ref. [11, 14, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34]).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of the study selection design.

| First author | Publication year and region | Age (years) | Subjects (cases) | Weeks of gestation | Exposure measure | Exposure | Covariates adjusted |

| Britte van Weert [20] | 2016, Netherlands | 8266 (2074) | 17 w | enzyme immunoassay method | 25(OH)D | maternal age, ethnicity, pre-pregnancy BMI, smoking and socioeconomic status | |

| Heather H. Burris [21] | 2014, USA | 2128 (1591) | 16.4–36.9 (27.9 w) | automated chemiluminescence immunoassay and a manual radioimmunoassay | 25(OH)D | maternal age, race/ethnicity, smoking, marital status, season of last menstrual period, education, parity, and gestational age | |

| Chui Ling Lee [22] | 2017, Malaysia | 30.0 |

680 (575) | 37 w | ultra performance liquid chromatography | 25(OH)D | age, BMI, and ethnicity |

| Piotr Domaracki [23] | 2016, Poland | 207 (171) | 25(OH)D | study group, gender, education, season, smoking habits, physical activity, alcohol intake, BMI and intake of fish | |||

| AW Shand [24] | 2010, Canada | 227 (221) | 10–20 w | radioimmunoassay kits | 25(OH)D | maternal age, height, blood pressure, parity, smoking status, current weight and date of vitamin commencement or pre-pregnancy vitamin usage | |

| Aya Mousa [25] | 2017, Australia | 228 (102) | direct competitive chemiluminescent immunoassays | 25(OH)D | age, BMI, parity, ethnicity, and smoking status | ||

| Kristi R. Van Winden [11] | 2020, USA | 559 (336) | immunoassay | 25(OH)D | birth season, maternal age, mode of delivery, race, infant gender, maternal HIV RNA and ARV regimen, and CD4 levels | ||

| Sanam Behjat Sasan [26] | 2017, Iran | 32.04 |

142 | 14.39 |

Liebermann-Burchard method | 25(OH)D | age, BMI, number of previous pregnancies, weeks of pregnancy, residence location, 24 h proteinuria |

| Linnea Bärebring [27] | 2016, Sweden | 31.3 |

2000 | LC-MS/MS (Mass spectrometer API 4000) | 25(OH)D | preexisting medical conditions, BP, weight, proteinuria, assisted reproduction, height, tobacco use and employment status | |

| Aisha Mansoor Ali [28] | 2019, Saudi Arabia | 20–40 | 179 (164) | competitive electro-chemiluminescence protein binding assay | 25(OH)D | fetal scans, personal data (parity, maternal age, BMI) | |

| Linnea Bärebring [29] | 2019, Sweden | 31.1 |

2125 (1413) | LC-MS/MS | 25(OH)D | birth place, season at conception, education level, parity, tobacco use | |

| Maria Stougaard [30] | 2018, Denmark | 284,179 (73,237) | 25(OH)D | singletons or multiple pregnancies; gender of the offspring; month of the delivery; months of delivery | |||

| Norma C. Serrano [14] | 2018, Colombia | 19.1 |

8407 (2028) | LC-MS/MS | 25(OH)D | race, maternal age, socioeconomic status, smoking status, multiple | |

| Gillian Santorelli [31] | 2019, British | 27.0 |

12,450 (1010) | 26 w | Waters Micromass Quattro Ultima Platinum Mass Spectrometer | 25(OH)D | infections during pregnancy, pregnancy, year of enrollment and health center |

| Camille E. Powe [32] | 2010, USA | 28.9 |

9930 (170) | LC-MS/MS | 25(OH)D | race, body mass index, nulliparity, season, and gestational age at blood collection | |

| Maria C Magnus [33] | 2018, UK | 7389 (886) | LC-MS/MS | 25(OH)D | pregnancy body mass index, age, smoking status during pregnancy, educational level, parity, serum calcium concentration | ||

| E Hyppönen [34] | 2007, UK | 4523 (2969) | commercial ELISA from immuno diagnostic Systems Limited and validation against an HPLC method | 25(OH)D | own birth order, birth weight, gestational age, social class in 1966 and hospitalizations or PIH of their mothers |

25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; ELISA, enzyme linked immunosorbent assay; BMI, body mass index; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; ARV, antiretroviral; CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; BP, blood pressure; LC-MS/MS, liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry; HPLC, high performance liquid chromatography; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

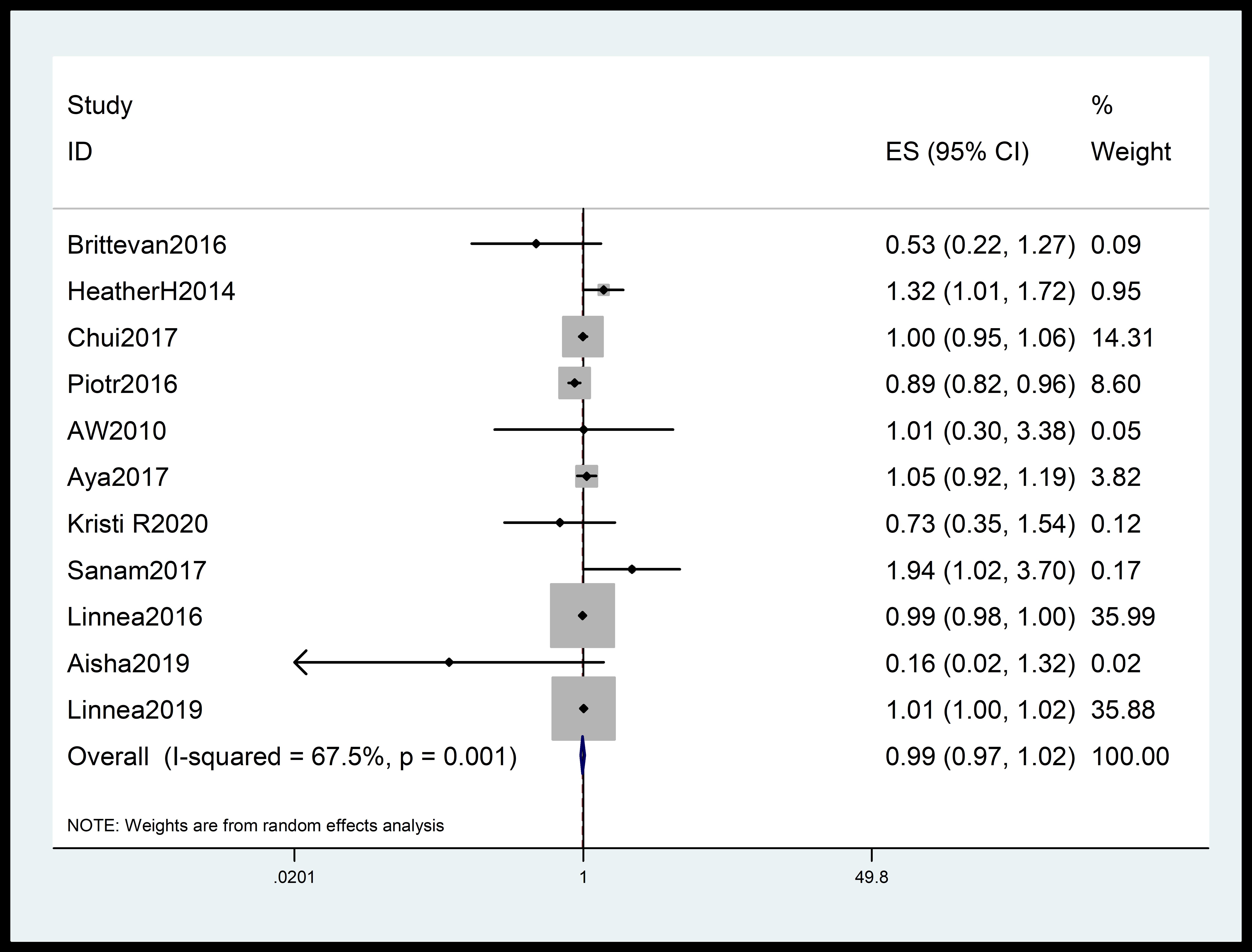

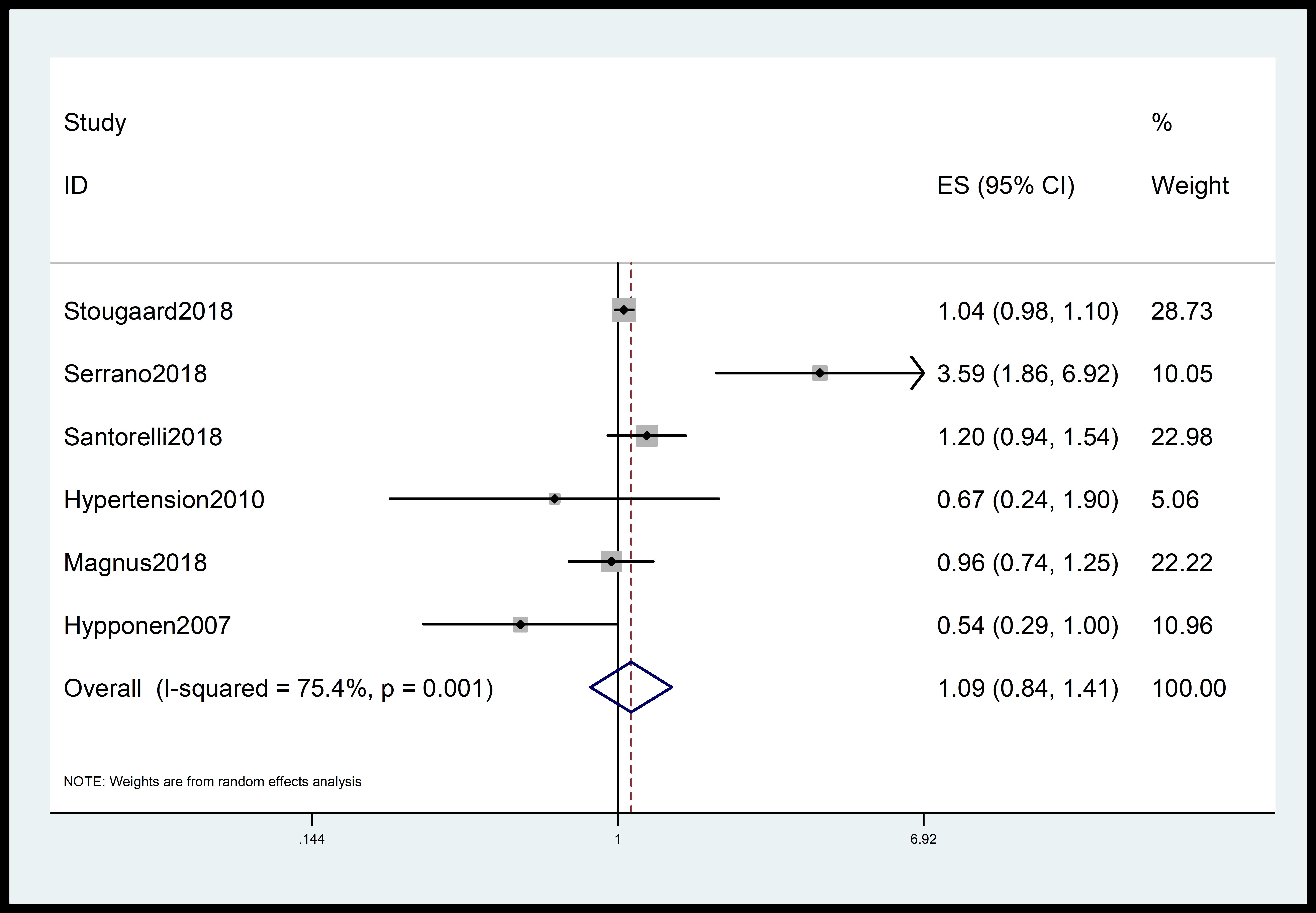

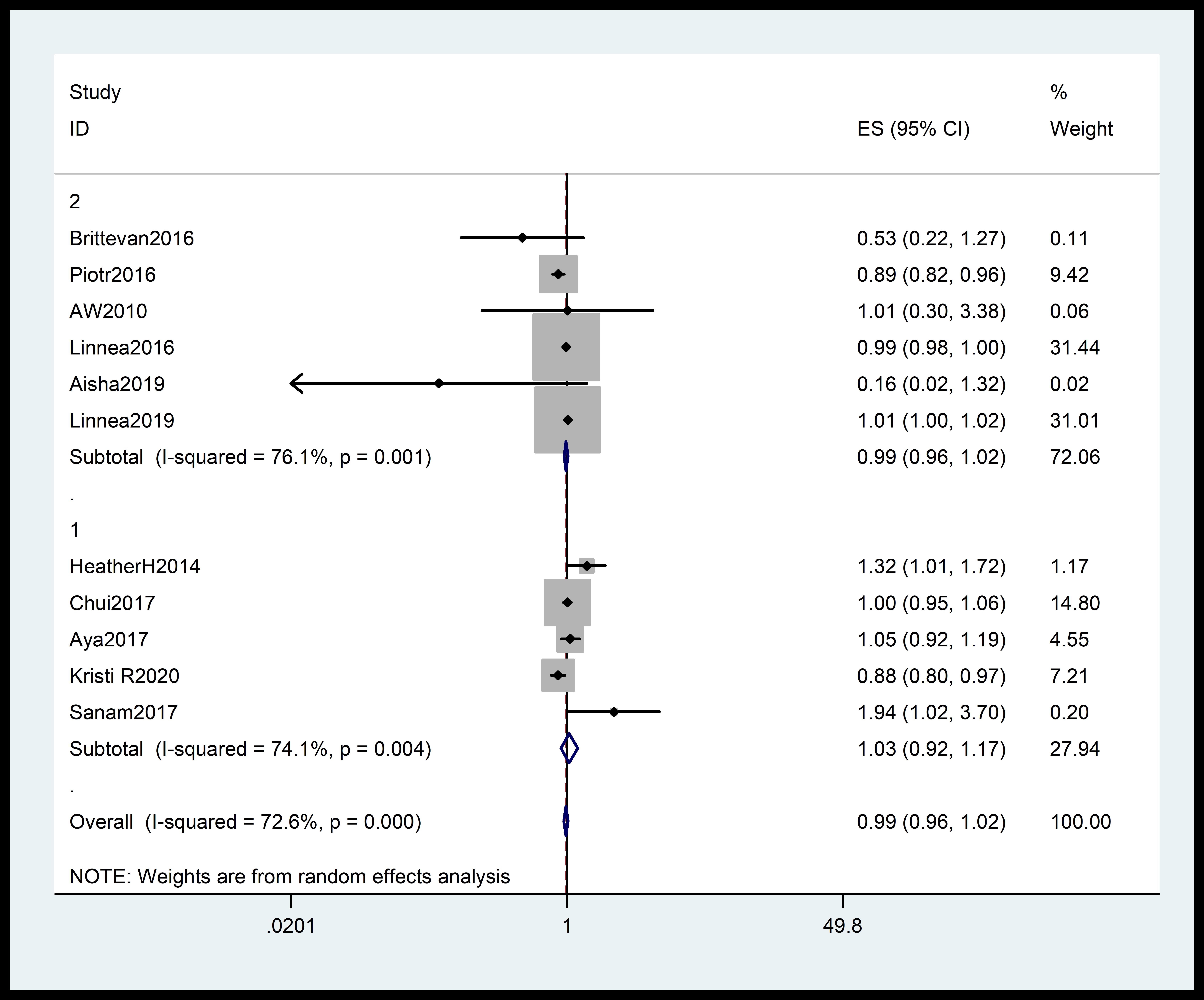

The meta-analysis incorporated data from 11 independent cohort studies [11, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29]. The analysis found a modest association between 25(OH)D levels and hypertensive disorders during pregnancy (95% CI: 0.97–1.02; summary RR = 0.99; I2 = 67.5%; p = 0.001) (Fig. 2). The meta-analysis of 6 case-control studies [14, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34] did not find an association between 25(OH)D and hypertensive disorders during pregnancy (summary RR = 1.09; 95% CI: 0.84–1.41; I2 = 75.4%; p = 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot quantifying the link between 25(OH)D and PIH. The summary RR was calculated using a random effects model. The diamonds show the summary estimate of the risk, and the horizontal lines show the 95% CI. 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D; ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval; RR, relative risk; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot quantifying association between 25(OH)D and gestational hypertension. The diamonds show the summary estimate of the risk, and the horizontal lines show the 95% CI. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval; 25(OH)D, 25-hydroxyvitamin D.

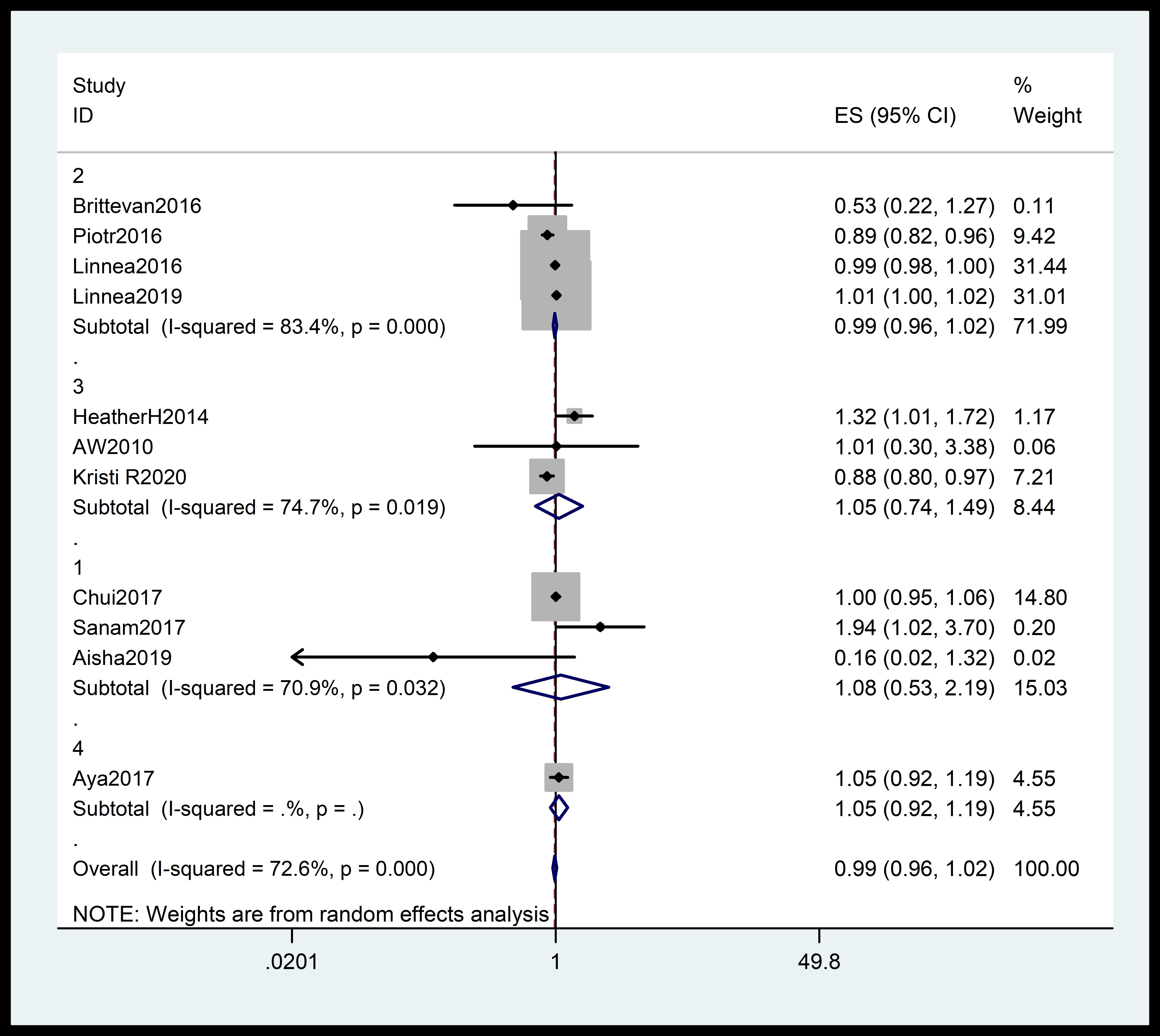

Subgroup analysis of the total incidence of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy indicated that 25(OH)D levels were only slightly associated with hypertensive disorders during pregnancy (95% Cl: 0.96–1.02; pooled RR = 0.99; I2 = 72.6%; p = 0.000) (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.

Subgroup analysis of the total incidence of gestational hypertension stratified by region. The diamonds indicate the summary estimate of the risk, and the horizontal lines indicate the 95% CI. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

Stratification of trials by study according to their quality revealed a borderline association between 25(OH)D and the risk of PIH in the high-dose group (pooled RR = 0.99, 95% CI: 0.96–1.02). In contrast, the medium quality group showed no statistically significant association (pooled RR = 1.03, 95% CI: 0.92–1.17) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

The trials were stratified according to the quality of the studies. The diamonds indicate the summary estimate of the risk, and the horizontal lines indicate the 95% CI. ES, effect size; CI, confidence interval.

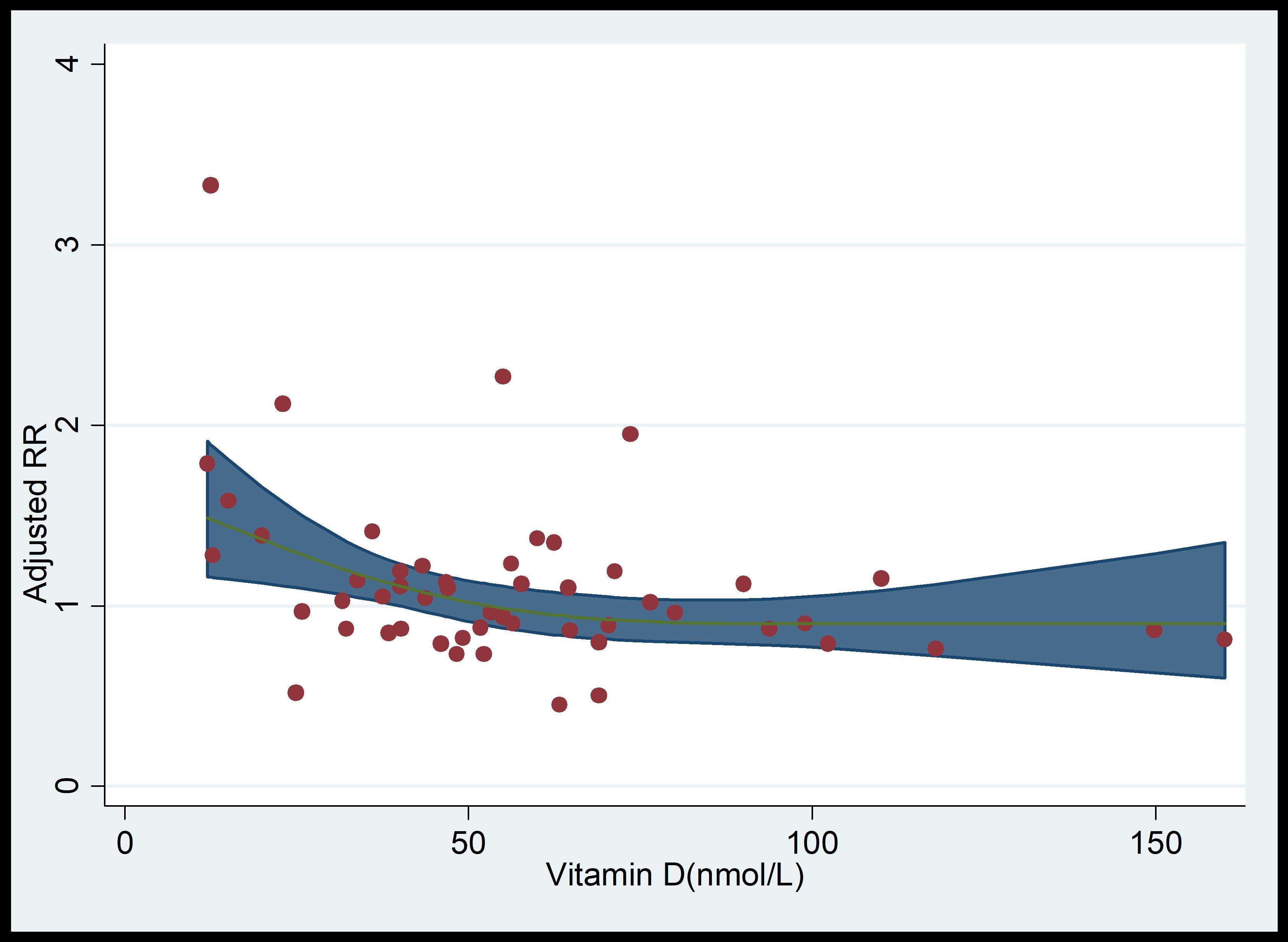

The dose-response analysis showed a marginal association between increased in vitamin D dosage and the incidence of PIH (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.

Dose-response analysis of vitamin D levels and PIH rates. RR, relative risk; PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

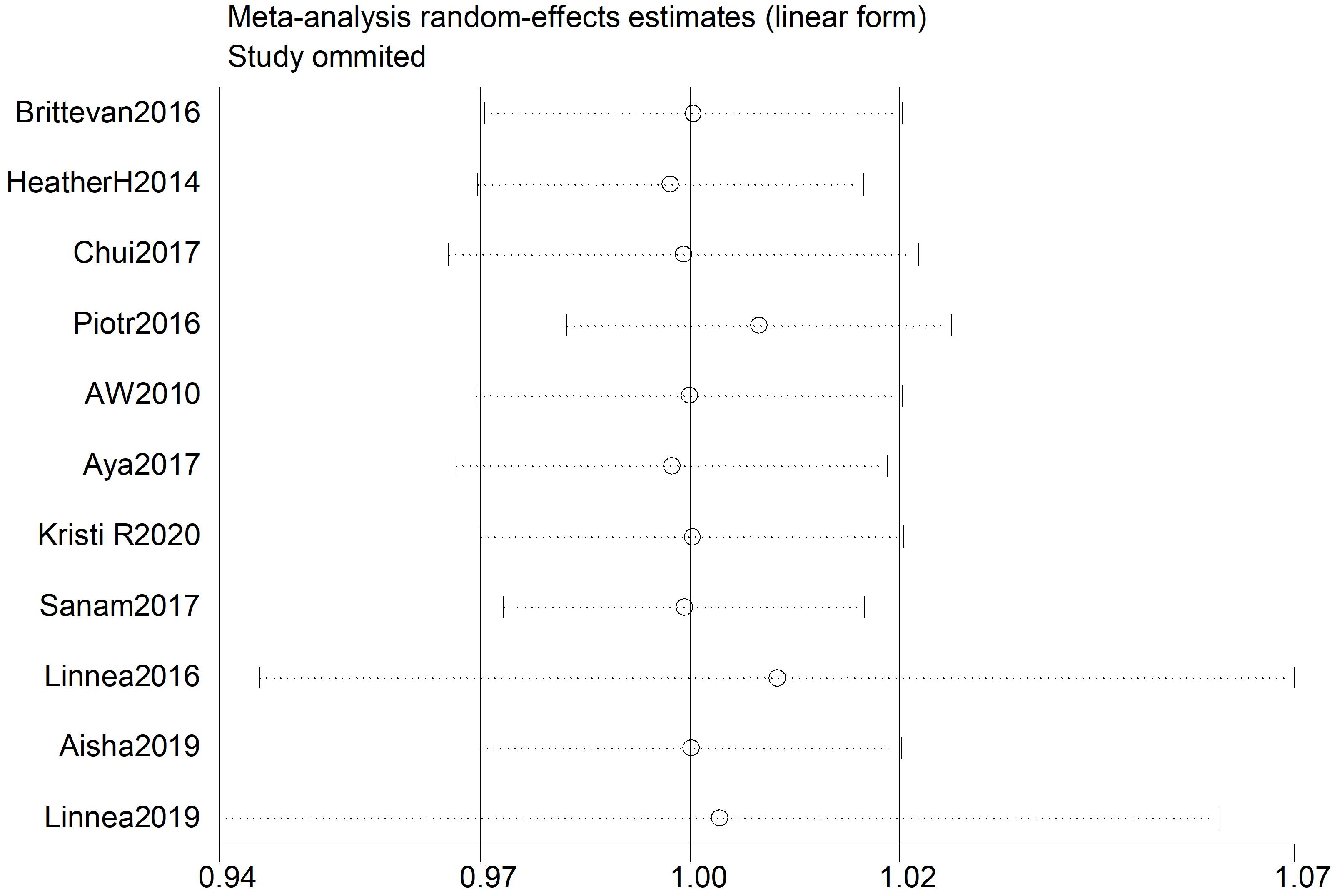

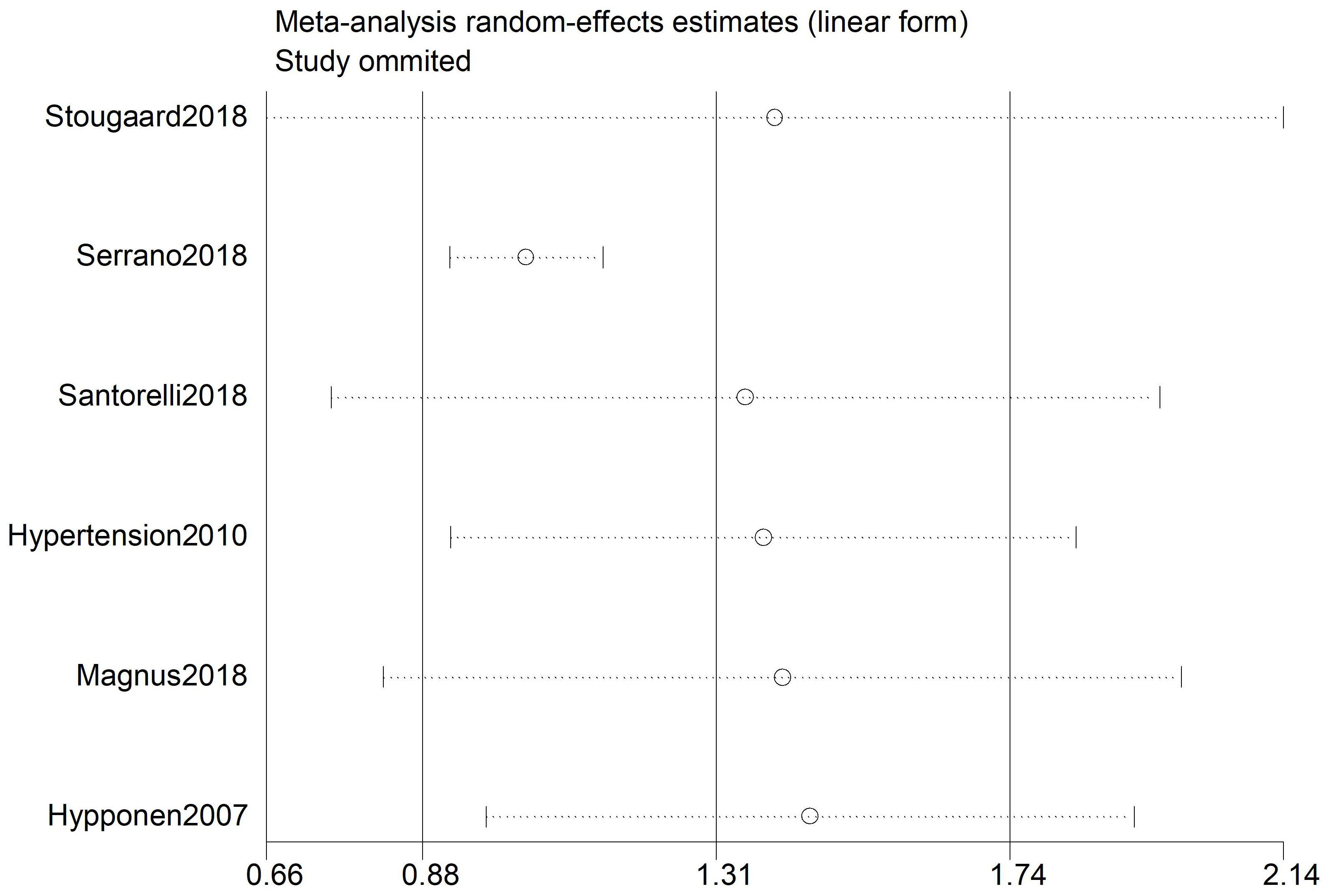

In a sensitivity analysis, each study was individually removed and the remaining

data were recalculated. The results showed that excluding any single study did

not significantly impact the combined estimate. Additionally, Egger’s regression

test revealed no significant publication bias analysis (p

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.

Sensitivity analysis in relation to vitamin D level and PIH of cohort study. PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

Sensitivity analysis in relation to vitamin D level and PIH of case-control study. PIH, pregnancy-induced hypertension.

Our results indicated a marginal association between 25(OH)D and PIH disorders based on the analyses of 11 cohort studies on PIH. Increase in vitamin D dosage was marginally associated with a decrease in the incidence rate of PIH. This finding indicates the vitamin D is marginally associated with pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders. Pregnant and lactating women are at increased risk of vitamin D deficiency due to their higher nutritional requirements. This is consistent with previous research, which suggests that low vitamin D levels may be associated with an increased risk of PIH [13, 35, 36].

Food is considered a poor source of vitamin D, as vitamin D is primarily produced endogenously by dermal synthesis. Vitamin D deficiency, particularly in high-risk populations and in northern latitudes, is mainly due to reduced exposure to sunlight. Vitamin D deficiency may also contribute to high blood pressure through its effects on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system [37]. Vitamin D supplementation may improve media and intimal compliance, as well as elasticity and thickness of blood vessels [38]. Our study highlights potential roles of vitamin D, suggesting that oral supplementation could be an effective method for addressing vitamin deficiency. According to the Endocrine Society, a vitamin D level below 20 ng/mL during pregnancy is classified as deficiency, and it is recommended to supplement with 400–600 IU of vitamin D daily [39]. However, studies have shown that a daily intake of 400–600 IU of vitamin D may be insufficient to prevent or treat gestational vitamin D deficiency, especially in women with exiting vitamin D deficiency and/or limited sunlight exposure [40]. Some studies have shown that there are no specific recommendations for vitamin D supplementation or food fortification policies during pregnancy [41, 42]. Our findings support the hypothesis that low levels of vitamin D may contribute to PIH. However, the role of vitamin D may be not as significant as previously thought.

However, research results are inconsistent. For example, Shand et al. [24] did not find a link between vitamin D deficiency and the risk of preeclampsia. Another study found no significant association between 25(OH)D levels and the incidence of PIH [11]. In the first trimester, although there was an association between maternal vitamin D levels and a reduced risk of preeclampsia, this association did not achieve statistical significance [43]. Another study has shown that vitamin D supplementation and exercise have the same effect as calcium supplementation in preventing preeclampsia and PIH [44]. Another study found no significant difference in 25(OH)D levels between preeclamptic and non-preeclamptic women, despite 80% of patients being vitamin D deficient [24]. Especially under physiological conditions such as pregnancy, 25(OH)D levels alone are unlikely to provide sufficient an accurate determination of vitamin D status [40]. While the majority of cross-sectional studies have found a significant association between lower 1,25(OH)2D levels and preeclampsia in the third trimester [45], it is important to consider the inherent limitations of such studies. Our research shows that vitamin D has a modest effect, but its impact is not substantial. Several ongoing studies are expected to provide further insights into this important issue the near future.

This review has some limitations. Firstly, some studies tested the vitamin D levels only once, and a single serum measurement may not accurately reflect the body’s overall vitamin D status. Additionally, we were unable to pool results based on sun exposure or ethnicity, as the majority of studies failed to provide information on these factors. Third, the use of various assay techniques to measure circulating 25(OH)D levels introduces variability. Finally, our analysis was limited to published studies. To confirm these findings, further research involving large, independent cohorts is necessary.

The current meta-analysis demonstrated that the risk of PIH may not be associated with vitamin D levels. Our findings support the hypothesis that gestational hypertension is not correlated with low vitamin D levels, suggesting that the role of vitamin D in this context may be minimal.

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

CC, XH and XL designed the research study. YC and SJ performed the research. XY and XL analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.ceog5109207.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.