1 Department of Clinical Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Zanjan University of Medical Sciences, 1439914153 Zanjan, Iran

2 Student Research Committee, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, 7134814336 Shiraz, Iran

3 Midwifery Department, Ministry of Health and Medical Education, 3143953579 Tehran, Iran

4 Department of Epidemiology and Biostatistics, School of Health, Social Determinants of Health Research Center, Birjand University of Medical Sciences, 9717853076 Birjand, Iran

Abstract

This review summarizes the molecular properties, anticancer effects, and bioavailability of quercetin (Que). We discussed its role in preventing and treating gynecologic cancers, assisting in the treatment of drug-resistant cases, and synergizing with other treatments. This review includes an analysis of Que’s impact on breast, ovarian, and cervical cancer.

Gynecologic cancers are a significant cause of cancer-related deaths, leading to low survival rates and a high burden on patients and healthcare systems. They are regarded as a major health problem in women. The use of complementary therapies, such as Que, can contribute to improving patient outcomes and the quality of life. The utilization of medicinal plants as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) is on the rise worldwide, offering new approaches to cancer treatment. This approach may provide potential treatments for various cancers, including female cancers such as breast, ovarian, and cervical cancer, either alone or in combination with other medications.

Among various natural compounds, Que is commonly used as an anti-cancer supplement due to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties. Que is effective in preventing and treating female cancers in a dose- and time-dependent manner, as demonstrated by numerous in vitro and in vivo studies and experiments. However, more clinical studies are required to establish this flavonoid as a therapeutic agent or as part of a drug combination in humans.

Que helps prevent and treat gynecological cancers, reduce drug resistance, and increase the effectiveness of chemical drugs and radiotherapy. It achieves this through its anti-inflammatory, pro-oxidative, anti-proliferative, induction of apoptosis, and cell cycle arrest mechanisms. However, more human studies are needed to accurately determine of the mechanisms of action and the extent of its effectiveness.

Keywords

- breast cancer

- ovarian cancer

- cervical cancer

- complementary medicine

- quercetin

Cancer is a common disease worldwide and is a major health challenge due to its high incidence and mortality [1, 2]. Gynecologic cancers are a significant cause of cancer-related deaths and represent a public health challenge for women [3, 4, 5]. Over 3.6 million people are diagnosed with these cancers annually, and more than 1.3 million deaths occur as a result, making gynecologic cancers responsible for approximately 40% of all cancer incidences and over 30% of all cancer-related deaths in women globally [6]. Therefore, there is a critical need to discover and develop new treatment approaches in the fields of prevention, treatment, and reduction of the burden associated with these cancers [7].

With the advent of poly adenosine diphosphate ribose (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitors, anti-angiogenic treatments, immunotherapy combinations, and targeted agents, significant advancements have been taken in the diagnosis and treatment of female cancers [8, 9]. In addition, in recent years, the use of medicinal plants as complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) has seen widespread globally as a novel approach in cancer treatment [10]. These plants ar used alone or in combination with other drugs for the treatment of various cancers [11]. On the other hand, affordable prevention and treatment options have become a priority for the medical community due to the high costs associated with current standard cancer treatments and the limitations of conventional treatments. Consequently, there is a growing attention on the interaction between diet and cancer [12].

Quercetin (Que) is recognized as a natural compound with anti-cancer properties due to its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory characteristics [13, 14]. It has shown potential in the treatment of various cancers, including breast [15], ovarian [16], and uterine cancers [17]. Additionally, formulating Que nanoparticles can improve its solubility, permeability, and enhance its therapeutic effect [18].

The primary food sources of flavanols include black tea (31%), onions (20%), apples (10%), citrus fruits (36%; 27% from oranges), and juices (63%; 54% from orange juice) [19]. Additionally, Que supplements are commercially available [20]. Importantly, Que’s potent cytotoxic effects on cancer cells are not linked with any negative side effects or harm to healthy cells [14].

Therefore, recognizing the ongoing need for advancements in the treatment of gynecological cancers, this review study aims to summarize the molecular properties, anti-cancer effects, and bioavailability of Que. It explores Que’s role in the prevention, treatment, assistance in the treatment of cases of drug resistance, and synergies with other treatments of gynecological cancers, including breast, ovary and cervix.

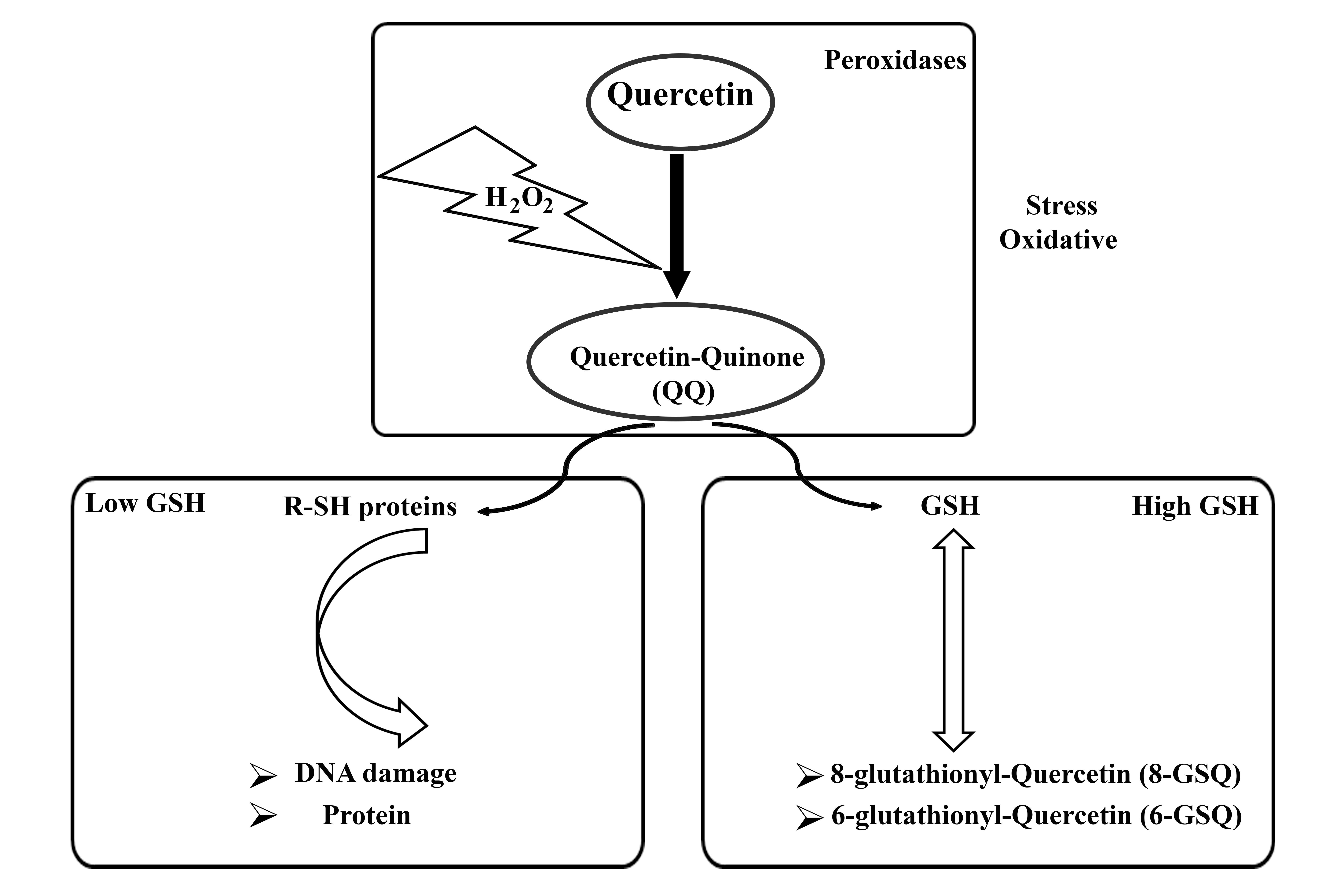

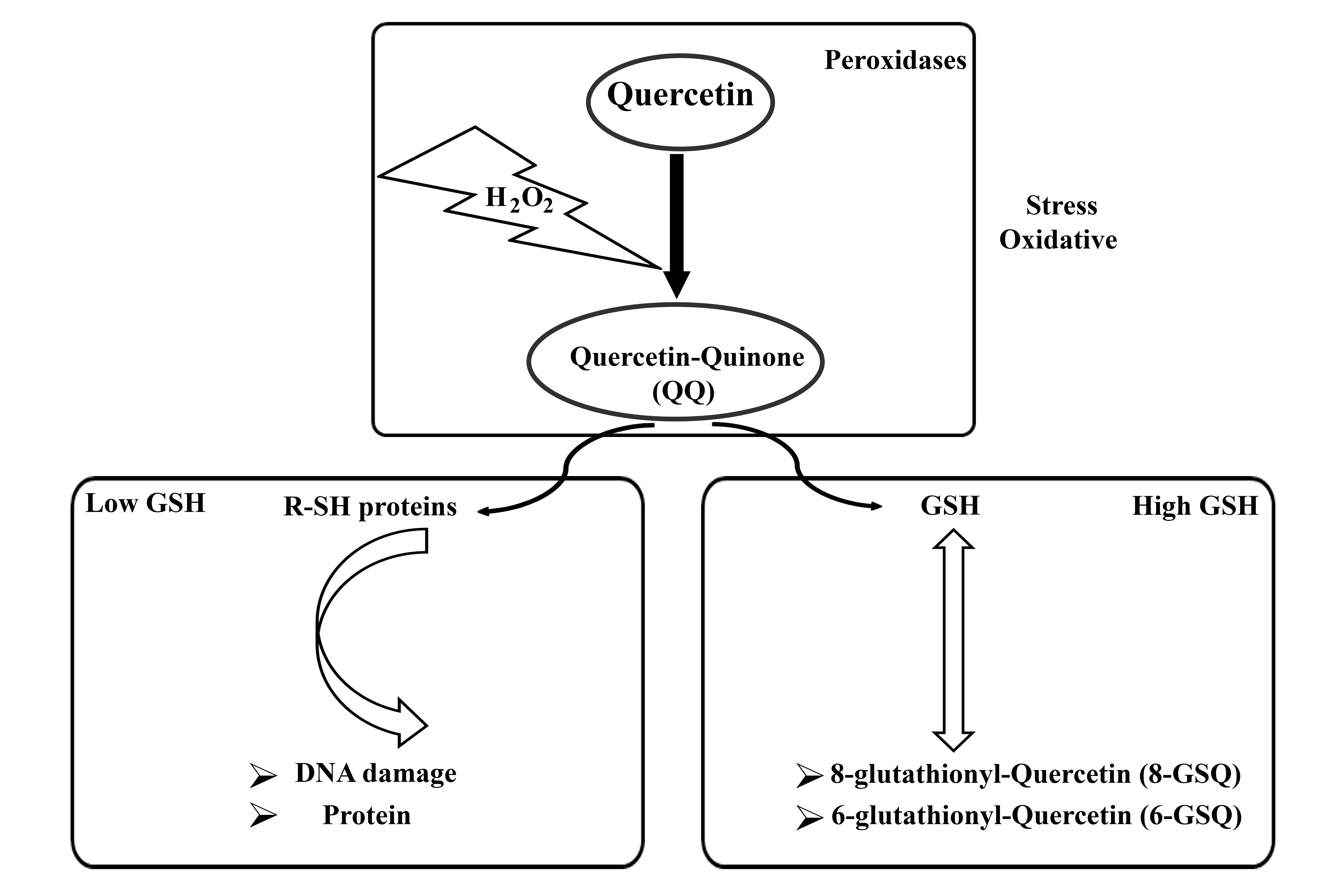

The concentration of Que determines its oxidative activity, with Que exhibiting antioxidant properties at low concentrations (1 µM) and acting as an oxidant at high concentrations (100 µM) [21]. In addition, the antioxidant activity of Que has been reported within the concentration range of 1–40 µM [22]. The oxidative activity of Que is influenced by the intracellular presence of glutathione (GSH). Under conditions of oxidative stress, Que reacts with hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) to form a semi-quinone radical, which rapidly oxidizes to Que-quinone (QQ). QQ exhibits a strong affinity for thiols, particularly reacting with GSH to form relatively stable protein-oxidized Que conjugates such as 6-glutathione-Que (GSQ-6) and 8-glutathione-Que (GSQ-8). This reversible nature of this reaction enables the continuous conversion of GSQ to GSH and QQ. When GSH levels are high, QQ reacts with GSH to produce GSQ, thereby preventing the cytotoxic effects of QQ. Conversely, in the absence of sufficient GSH, QQ can react with protein thiols, leading to cell damage [23]. The molecular properties of Que are summarized in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Molecular properties of quercetin in summary. H2O2, hydrogen peroxide; GSH, structure of glutathione; R-SH, structure of Thiols.

Bioavailability is defined as the ratio between the amount of substance administered orally and the amount that is absorbed and used for physiological activity or storage [24]. Que is absorbed through bioabsorption in two forms: as a free or aglycone form, and in combination with various substances [25]. Compounds such as carbohydrates, sulfates, lipids, and alcohols can conjugate with Que, thereby increasing its bioavailability [25]. Dietary fat aids in the micellization of Que, thereby increasing its bioavailability. Encapsulation of Que with lipid particles, with an efficiency of 75–87%, increases the chemical stability of Que under digestive conditions by 44% and increases its solubility in the aqueous liquids of the digestive tract by more than 73% [26, 27]. Cortisone in foods typically binds to a sugar molecule, forming what is called a glycoside. Que-3-glucoside (isoquercetin) is formed in onion plants by binding with glucose, while apple trees and tea plants are known to produce Que [28]. Bioavailability can be affected by multiple factors, such as glucoside formation, solubility, age, sex, vitamin C status, and the food matrix. Additional research is needed to assess and improve the bioavailability of Que [29]. In general, Que exhibits affinity for fats due to its low water solubility. Its bioavailability is limited by its poor solubility and crystalline form at body temperature [30].

Que is a widely used dietary supplement and phytochemical drug for treating a variety of illnesses [31], despite its challenges such as poor solubility, low bioavailability, poor permeability, and instability [32]. To enhance Que’s bioavailability and solubility, various methods have been employed, emphasizing promising drug delivery systems like inclusion complexes, liposomes, nanoparticles, or micelles [32].

Que can significantly inhibit various cancers such as breast, lung, gastric, ovarian, colorectal, and hepatic cancers [33]. Que’s anticancer effects can be attributed to multiple mechanisms. These processes include inducing cell apoptosis, inhibiting angiogenesis, blocking P-glycoprotein (P-gp) channels, decreasing oncogene expression, and regulating signaling pathways [34]. The induction of apoptosis induces the anticancer function of Que by activating p53 in cancer cells, while it can prevent apoptosis in normal and healthy cells [35]. Que at concentrations of 10, 20, 40, 80, and 120 µm improved apoptosis induction in human ovarian cancer (CHO) and breast cancer (MCF-7) cell lines [36]. In different cell lines (CRL-1978, CRL-11731, SK-OV-3), treatment with 6.25 µM 3,4′,7-O-trimethylquercetin (34′7TMQ) increased the expression of the pro-apoptotic proteins such as Bax/Bcl-2, p38 Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase (MAPK), and caspase-9 increases [37]. Que can increase the efficacy of anticancer drugs by inducing apoptosis [38]. Angiogenesis significantly affects the pathogenesis and metastasis of cancer. In the study by Pratheeshkumar et al. [39], they evaluated Que’s anti-angiogenic activity using ex vivo, in vivo, and in vitro models. They concluded that Que at concentrations of 10–40 µM significantly inhibited the proliferation of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)-induced human umbilical vein endothelial cells (HUVECs) in a chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) assay. Additionally, they reported that Que at a concentration of 20 µM inhibited VEGF-induced angiogenesis in the Matrigel plug assay. As a result, Que caused a dose-dependent decrease in vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) phosphorylation, thereby slowing down cancer growth [39]. In addition, the anti-inflammatory [40, 41], antioxidant [42], moisturizing [42], antiallergic [43], and anti-melanogenesis [44] properties of Que can contribute to the prevention and treatment of cancers.

Despite the mentioned benefits of Que in anticancer therapy, its use as a supplement in cancer patients should be approached cautiously due to possible drug interactions with antibiotics, anticoagulants, corticosteroids, cyclosporine, and chemotherapy. It is important to take necessary precautions under the guidance of a doctor [45]. On the other hand, potential side effects of que overdose should also be considered, such as nausea, abdominal discomfort, or interference with thyroid function [46].

The incidence and severity of breast cancer increase with the presence of BRCA1/BRCA2 mutations, family history of disease, especially in first- and second-degree relatives, and age over 40 years [47]. Inherited gene mutations account for approximately 10.5% of breast cancers [48, 49]. Mutations BRCA1/BRCA2 [50, 51, 52], PALB2 [52], and RANKL/RANK have been reported as significant genetic factors in the onset of breast cancer [53, 54, 55]. Mutations BRCA1/BRCA2 have been found in 97% of breast cancer patients [56]. Additionally, the risk of breast cancer is higher with the overexpression of HER2, Ki-67, and the presence of Luminal A, Luminal B, and Basal subtypes [57]. On the other hand, the prediction of breast cancer incidence can be influenced by the expression of progesterone receptor (PgR). PgR was confirmed to be present in 77.2% of patients with estrogen receptor-positive (iodine-positive) primary breast cancer [58].

Triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) encompasses a diverse set of breast cancer types with varied genetic origins and distinct signaling pathways [59]:

(a) basal-like 1 (BL1): characterized by genes associated with cell proliferation, DNA damage repair genes, and the expression of the Ki-67 protein.

(b) basal-like 2 (BL2): characterized by genes involved in the growth factor signal pathway and genes of metabolic signal transmission.

(c) immunomodulatory (IM): characterized by genes involved in safety-related signal pathways and cytokine-related signal pathways.

(d) mesenchymal (M) and (e) mesenchymal stem-like (MSL): characterized by genes involved in epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) and genes associated with cell differentiation.

(f) luminal androgen receptor (LAR): characterized by androgen receptor signaling pathways.

Que can induce apoptosis in breast cancer cells by regulating the expression of

IFNy-R, p-JAK2, p-STAT1, and PD-L1 in the JAK/STAT1 signaling pathway, as well as

modulating T cell activity. Que can prevent precancerous changes in breast tissue

and assist in the treatment of breast cancer [60]. The Wnt/

Que has been under investigation as an alternative treatment for breast cancer

for several years. Que has been extensively researched for decades as a potential

treatment for breast cancer. Multiple studies have examined its effect on breast

cancer in laboratory settings, demonstrating that Que prevents breast cancer

development by lowering cellular survival in the G2/M phase [63, 64, 65, 66, 67, 68], inducing

apoptosis through the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) via

AMP-activated protein kinase [68, 69], and affecting proliferation effect [67, 68]. These effects have been found to be dose- and time-dependent, varying based

on the type of breast cancer [70]. Que has also been shown to prevent breast

cancer metastasis by reducing AKT/mTOR activity, inhibiting cell invasion and

migration, and inducing autophagy [71, 72]. Que treatment generally results in a

reduction in AKT phosphorylation and a decrease in the activity of downstream

target proteins, including glycogen synthase kinase 3 alpha/beta

(GSK3

According to the results of Duo et al. [79], Que, at doses of 50 to 200

µM, Que significantly inhibits the proliferation of MCF-7 human breast

cancer cells (p

Increasing the water solubility and stability of Que by creating biocompatible and biodegradable Que nanostructured lipid carriers (Que-NLC) with a diameter of 32 nm can: (1) increase the cellular toxicity in dose-dependent manner (1–50 µM), (2) increase apoptosis at 20 µM in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells, and (3) enhance the effectiveness chemotherapy in breast cancer. Cell toxicity and increased apoptosis are correlated with increased Que absorption by these cancer cells [80].

Elbeltagi et al. [81] demonstrated that the in vitro toxicity

assessment of Que-loaded magnetoliposome lipid (Que-MLs) bilayer hybrid system on

MCF-7 breast cancer cells concluded that que-loading on the Que-MLs surface

improved. They also reported that the drug loading and entrapment efficiency of

Que were 2.1

In the study by Hatami et al. [82], after treating MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells with 18.9 µM of Que and Que-SLN for 48 h and investigating its anti-cancer effects on the triple-negative breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231, found that Que-SLN exhibited optimal properties, such as particle size of 154 nm, zeta potential of –27.7 mV, encapsulation efficiency of 99.6%, and drug loading of 1.81%. It also showed sustained release of Que over 72 h. Furthermore, the Que-SLN group showed significantly lower cell viability, reduced colony formation, inhibited angiogenesis, and a higher levels of apoptosis due to the modulation of Bax and Bcl-2 at both gene and protein levels. The increase in the ratio of cleaved-to-pro caspases 3 and 9, as along with PARP, induced by Que-SLN, was prominently observed in both cancer cell lines.

Chien et al. [83] observed an additive increase in p53 activation, caspase-9 activation, caspase-3 activation, cytochrome c release, and apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells treated with 200–250 µM of Que. They also found a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential indicative of mitochondrial-mediated apoptosis.

Que suppresses the proliferation of breast cancer stem cells, inhibiting their self-regeneration and aggressiveness. It reduces the expression levels of proteins associated with tumor formation and cancer progression, such as aldehyde dehydrogenase 1A1, C-X-C type 4 chemokine receptor, mucin 1, and epithelial cells adhesive molecules [84].

Que induces apoptosis in MCF-7 cells and inhibits the proliferation of MCF-7 breast cancer cells in a time- and concentration-dependent manner. The level of mRNA and survivin protein expression decreased as Que concentrations increase. Que arrest the growth of MCF-7 cells and induce apoptosis by inducing phase-stopping G0/G1. The regulation of survivin gene mRNA expression in MCF-7 cells may underlie the antitumor effects of Que [85].

In summary, Que affects human breast cancer cells MCF-7 by inhibiting cell growth and inducing apoptosis. These effects are attributed to a decrease in Bcl-2 expression and the positive regulation of Bax expression [79, 86].

More details about the role of Que nanoparticles are summarized in Table 1 (Ref. [82, 87, 88, 89, 90, 91, 92, 93, 94, 95]).

| First author (year) | Cell type | Cell line | Nanoparticle | Characteristics | Dose and time | Main result |

| Hatami et al. (2023) [82] | - | Triple-negative breast cancer cell line MDA-MB-231 | Que-solid lipid nanoparticles (Que-SLN) | The particle size of 154 nm, zeta potential of –27.7 mV, encapsulation efficiency of 99.6%, and drug loading of 1.81% | 18.9 µM of Que and Que-SLNs for 48 h | The Que-SLNs enhanced the physicochemical properties and sustained Que release, causing a reduction in cell viability, colony formation, angiogenesis, and increased apoptosis in the MDA-MB-231 cell line. |

| Niazvand et al. (2019) [87] | Human cell | MCF-7 and MCF-10A (non-tumorigenic cell line) | Que-SLNs | The particle size of 85.5 nm, a zeta potential of −22.5 and an encapsulation efficiency of 97.6% | 25 µmol/mL Que-SLNs for 48 h | The toxic effect of Que on human breast cancer cells was significantly enhanced by SLNs. |

| Sorayabin Mobarhan et al. (2022) [88] | Human cell | MCF7 and BT474 breast cancer cell lines | Que and doxorubicin (Que-DOX) | - | 10, 20, 40, 80 and 160 of Que and 1, 2.5, 5 and 10 µg/mL of doxorubicin d for 24 h | Cancer cells were more effectively inhibited by Que-DOX. |

| Hatami et al. (2023) [89] | MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells | Que-SLNs | Particle size of 154 nm, zeta potential of −27.7 mV, and encapsulation efficacy of 99.6% | 18.9 µM and 13.4 µM of Que-SLNs for 48 h | The cytotoxic effect of Que in MDA-MB-231 cells can be effectively suppressed with the use of SLNs, which increases its bioavailability and inhibits epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT), resulting in reduced CSC generation. | |

| Sarkar et al. (2016) [90] | - | - | Folic acid (FA) armed mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSN-FA-Q) | Average size below 200 nm | - | Enables targeted delivery with improved bioavailability. |

| Bose et al. (2020) [91] | Sprague Dawley rats | Light-activated chemo-photothermal therapy of DMBA | QRC-FA-AgNPs | Plasmon tunability in the NIR region (~860 nm) | - | Que’s antitumor efficacy was enhanced by the photothermal effect of the silver nanocarrier, which caused hyperthermia and selectively killed cancer cells, leading to apoptosis. |

| Mohammed et al. (2021) [92] | Murine | CAL51 and MCF7 cell lines | Poly(d,l)-lactic-co-glycolic acid (PLGA)-encapsulated Que nanoparticles (Que-PLGA-NPs) | - | - | The liver and kidney functional biomarkers were unaffected and there were no abnormalities or tissue damage detected in histological images. |

| Lv et al. (2016) [93] | Human | Doxorubicin-resistant breast cancer cells line MCF-7 | Biotin-decorated poly (ethylene glycol)-b-poly(ε-caprolactone) nanoparticles encapsulating doxorubicin and Que (BNDQ) | Particle sizes 90.2 |

- | Inhibition of both P-glycoprotein activity and expression by BNDQ was evident in MCF-7/ADR cells. |

| Alkhaldi et al. (2024) [94] | Human | Breast cancer cell line MCF-7 | Que nanoparticles | Anticancer drug mitoxantrone (MTZ) by loading it into an emerging nanomaterial derived from the plant polyphenol quercetin | 1–100 µM of Que nanoparticles at the 24th, 48th and 72nd h | The nonopatticles’ proapoptotic effect was enhanced in the presence of curcumin or thymoquinone, depending on the cell line. |

| Askar et al. (2022) [95] | White albino rats | MCF-7, HePG-2, and A459 cancer cells | Que-conjugated magnetite nanoparticles (QMNPs) | Spherical shape with a diameter of 40 nanometers | 11, 77.5, and 104 nmol/mL for 24 h | MCF-7 cells’ vitality, growth rate, and colony formation could be significantly reduced by Que-NPs. |

DMBA, Dimethyl Benz(a)anthracene; Que, quercetin; Que-SLN, que-solid lipid

nanoparticles; Que-DOX, Que and doxorubicin; FA, folic acid; MSN-FA-Q, armed

mesoporous silica nanoparticles; QRC-FA-AgNPs,

quercetin-folate-receptor-targeted-plasmonic

silver-nanoparticles; PLGA, poly(d,l)-lactic-co-glycolic acid; Que-PLGA-NPs,

PLGA-encapsulated Que nanoparticles; BNDQ, Biotin-decorated poly(ethylene

glycol)-b-poly(

Que at concentrations of less than 100 µM enhances the pharmacological effects of doxorubicin and reduces drug resistance and toxicity in 4T1 breast cancer cells of BALB/c mice under hypoxic conditions [96]. Que reduces drug resistance by inhibiting the activity and/or expression of P-gp [97]. Que at a concentration of 0.7 µM has been reported to reduce Dox drug resistance in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells [98]. Additionally, Que at a concentration of 10 µM can increase the efficacy of 100 µM doxorubicin [99]. Furthermore, it has been reported that Que at concentrations of 25, 50, and 100 µM reduced the growth of cancer cells by 59.5%, 74.3%, and 90.3%, respectively [100]. In another study, Que was reported to reduce the expression of breast cancer resistance protein (BCRP) and P-gp in 4T1 cancer cell lines in BALB/c mice, thereby decreasing the toxicity and drug resistance of doxorubicin [101]. Additionally, Que’s effect on the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway was confirmed in a study on breast cancer stem cells (BCSC) resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy. CD44+ BCSC isolated from MCF-7 cells exhibited decreased cell viability and metastatic properties upon treatment with 50 µM Que [15]. It has been shown that the cytotoxic activity of docetaxel is enhanced in the presence of Que (40 µM) in MCF7-DR (drug resistance) cells. This enhancement is due to the downregulation of lymphoid enhancer factor 1 (Lef1), which increases the intracellular concentration of docetaxel and enhances its synergistic effect [102].

The flavonol-mediated enhancement of paclitaxel’s cytotoxic effect is a factor that counteracts chemotherapy resistance in the MCF-7/ADR cell line, which is resistant to doxorubicin. The overexpression of P-gp in these cells results in a significant export rate for this glycoprotein, contributing to drug resistance. This chemical resistance is reduced by Que at a maximum concentration of 10 µM [103]. Moreover, Que (0.7 µM) has been proven to reduce the cytotoxic effects of doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and vincristine by lowering the levels of P-gp and inhibiting the nuclear transfer of Y-box binding protein 1 (YB-1) [104]. YB-1 is a transcription factor known to be associated with cell proliferation and drug resistance in breast cancer. It translocates into the nucleus following phosphorylation mediated by AKT/mTOR or p90RSK pathways. Que’s potential to inhibit AKT/mTOR signaling offers a mechanism to potentially inhibit YB-1 [72].

The synergistic effect of Que with tamoxifen, docetaxel, cisplatin (CDDP), and fluorouracil has been reported in various studies. The synergistic response with co-treatment of 0.5, 1.8, and 2 µM Que and tamoxifen in vitro has been confirmed by Paulpandi et al. [105]. The combination of 7 nM docetaxel and 95 µM Que has also been shown to exhibit a synergistic effect, induction apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cells. This synergy involves an increase in the expression of p53-associated protein X (PAX) and Bax [106]. In a study by Liu et al. [107] using an EMT6 tumor transplant mouse model, co-administration of Que with cisplatin was reported to be more effective in reducing cancer size and mitigating cisplatin-induced cytotoxic effects in breast cancer compared to cisplatin alone. In investigating the synergistic effect of 5-fluorouracil and Que in the MDA-MB-231 cell line, it was observed that besides reducing cell viability, the combination also inhibited cell migration [108]. Furthermore, an increase in the rate of apoptosis in the MCF-7 cell line due to the synergy of 5-fluorouracil and Que has been reported [109]. MCF-7 and BT-20 cell lines resistant to tumor necrosis factor–related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) were used to investigate the combined effects of Que and anti-neoplastic drugs. After 72 h of treatment with CASP8 and FADD-like apoptosis regulator (c-FLIP), it was observed that Que (at a maximum concentration of 50 µM) induces proteasomal degradation and enhances the pro-apoptotic effects of recombinant human TRAIL (rhTRAIL) by increasing the expression extrinsic apoptosis receptor 5 (DR5) [110]. The underlying mechanism of this effect warrants further consideration in additional studies.

There are five primary types of epithelial ovarian cancer: high-grade serous carcinomas (HGSC), endometrioid carcinomas (EnC), clear cell carcinomas (CCC), mucinous carcinomas (MC), and low-grade serous carcinomas (LGSC) [111, 112, 113]. These subtypes are distinct both clinically and molecularly [114]. The origin of HGSC is from the epithelium of the terminal fallopian tubes, while endometrioid clear cell (CC) and ovarian carcinoma (OC) originate from endometriosis [115, 116]. BRCA1/BRCA2 and MAPK are two important molecular pathways in ovarian cancer [117]. Common gene mutations known in ovarian cancers include TP53, BRCA1/BRCA2, PIK3CA, and KRAS. The p53 mutation is the most prevalent mutation in HGSC [118, 119], and the majority of hereditary OC cases are linked to the BRCA1/BRCA2 genes [120]. In EnC and CCC, PIK3CA mutations are more common [121, 122]. In LGSC and MC, KRAS mutation play a key role [122, 123]. These mutations play a role in ovarian tumorigenesis through mechanisms involving abnormalities in DNA repair gene, apoptosis, loss of function in tumor suppressor regulatory genes, increased function of oncogenes, and epigenetic inactivation [124].

A study revealed a significant decrease in ovarian cancer among individuals who consumed more than one glass of black tea daily, compared to those who never or rarely drank black tea [19]. Furthermore, the consumption of vegetables fruits rich in Que, such as apples and citrus fruit juice, has been associated with reduced risk of ovarian cancer [125, 126, 127, 128]. However, in two separate studies by Gates et al. [129, 130] no connection was found between Que intake and decreased risk of ovarian cancer.

Xu et al. [131], using a heat-sensitive injectable hydrogel system

loaded with Que (Que-M-hydrogel composites) based on nanotechnology, demonstrated

enhanced effects in inducing apoptosis and inhibiting cell growth inducing

apoptosis and inhibiting cell growth in SKOV abdominal ovarian cancer mouse

models compared to other groups. They concluded that the prepared Que-M-hydrogel

composites enhanced antitumor activity by providing a high local concentration of

Que, sustained drug release, prolonged drug retention within the tumor, and

minimal toxicity to normal tissues [131]. When Que is formulated as monomethoxy

poly (ethylene glycol)-poly(

Drug resistance accounts for 90% of deaths among ovarian cancer patients [135]. The use of herbal compounds along with chemotherapy can reduce drug resistance [136]. Previous studies have shown that Que (0.01 to 100 µM) reduces the drug resistance of cisplatin (CDDP) [137, 138]. Zhang et al. [139] using Chinese bayberry leaf flavonoids (BLF) that contained a rich content of myricetin and Que (Que 3-rhamnoside) showed that treatment with BLF at 2 mg/mL improved drug resistance in ovarian cancer. These findings indicated that BLF slowed the growth of the A2780/CP70 ovarian cancer cell line, decreased cell viability, and induced apoptosis in A2780/CP70 ovarian cancer cells. Catanzaro et al. [137] incubated A431, C13, and A431Pt cancer cells with 10 µM of the compound for 24 h and found that Que arrested the cancer cell cycle and promoted the apoptotic pathway.

Another study also demonstrated that incubating SKOV3 the human ovarian cancer cells with Que (50 µM) for 48 h significantly reduced the expression level of cyclin D1. However, this effect was not observed in SKOV3/CDDP cells [140]. In another study, the treatment of Que at different concentrations in combination with cisplatin, taxol, pyrarubicin and 5-Fu was investigated in C13 and SKOV3 cells of human epithelial ovarian cancer. It was shown that contrary to the proapoptotic effect of high concentration (40 µM to 100 µM) of Que, low concentrations (5 µM to 30 µM) of Que, when combined with cisplatin, reduced oxidative stress induced by cisplatin chemotherapy. Furthermore, when a low dose of Que (5 µM to 30 µM) is combined with cells treated with 80 µM cisplatin in the ovarian cancer cell line C13, the drug toxicity decreases. However, with a high concentration of Que (100 µM), the drug toxicity increases. Low concentrations of Que reduced oxidative stress induced by chemotherapy with cisplatin, and increased the expression the endogenous antioxidant enzyme superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) in ovarian cancer cells in vivo [141]. Chen et al. [142] observed that Que can reduce the cardiotoxicity of doxorubicin administered in the SKOV-3 ovarian cancer cell line.

In the study of Wang et al. (2015) [143], it was reported that Que, present in blueberries and converted to its aglycone state, induced apoptosis, activated caspase-3, inactivated PARP, and increased sensitivity to cisplatin. This led to decreased cell viability in ovarian cancer cells in SKOV-3 and OVCAR-8 cell lines. Comparing the effect of an anticancer cocktail prepared by simultaneous loading of GO-polyvinylpyrrolidone-quercetin-gefitinib (GO-PVP-QSR-GEF) and with individual combinations of Que and gefitinib showed that Que increases the anti-cancer effects of gefitinib chemotherapy in IOSE-364 ovarian epithelial cells [144]. Moreover, low doses of Que (1–5 µM) have been shown to increase in vitro sensitivity of human ovarian cancer cell lines, including SKOV-3, EFO27, OVCAR-3, and A2780P, to cisplatin and paclitaxel [145]. Que also reduces drug toxicity in C13* and SKOV3 cancer cells both in vitro and in xenograft tumor models [146].

Human papillomavirus (HPV) infection is the primary cause of cervical cancer [147, 148, 149]. HPV is responsible for setting off the initial and crucial phases in the neoplastic progression of cervical lesions through infection [150, 151]. Early changes in epithelial cells can be attributed to the viral oncoproteins E6 and E7 [152]. Interference with the DNA methylation machinery and mitotic checkpoints is another oncogenic property of these viral oncogenes (E6 and E7) [151]. High-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN) lesions are defined as precancerous lesions where viral oncoproteins are aberrantly expressed in dividing cells [151]. These oncoproteins control the normal cell cycle by inactivating of p53 and retinoblastoma (Rb), which are two main tumor suppressor proteins [151, 152].

Inactivation of these proteins in the host disrupts DNA repair and apoptosis

mechanisms, leading to rapid cell proliferation [150, 152]. In CIN and cancer, multiple genes play a role in DNA

repair, cell proliferation, growth factor activity, angiogenesis, and mitogenesis

[152]. Apolipoprotein B-like mRNA editing enzyme catalytic polypeptide (APOBEC),

a DNA editing protein, plays a vital role in the molecular pathogenesis of

cancer. Specifically, aberrant DNA editing mechanisms in the APOBEC3 family have

been found to be responsible for tumor mutations. The activity of APOBEC3 enzymes

facilitated their domination in editing DNA and RNA, crucially regulating diverse

biological processes including protein expression regulation, immune response,

and embryonic development. Retroviruses, endogenous retroelements, and DNA

viruses, including HPV—an important risk factor for cervical cancer—are

restricted by the intrinsic antiviral activity of APOBEC3 family members [153].

In general, research has shown that the Wnt/

Que is a well-known chemopreventive agent for cervical cancer and its ability to

regulate the expression of tumor suppressor miRNAs is a useful tool in preventing

cervical cancer. Que is described to elevate the expression of tumor suppressor

miRNAs miR-26b, miR-126, and miR-320a in vivo and in vitro

studies, and by regulating miR-320a, leading to suppressed levels of

Que can have an impact on a limited number of cellular processes, such as cell proliferation, growth, viability, survival, and migration [160]. Que is known to stimulate the ER stress pathway, resulting in cell death and apoptosis [161, 162, 163, 164]. GRP78 and CHOP, which are cleaved ER stress markers and caspase-4, have been shown to increase the presence of Que, leading to apoptosis in ovarian cancer cell lines and primary ovarian cancer cells [16, 165]. Que has also been shown to promote cell motility through epithelial-mesenchymal transition signaling, inhibiting the invasiveness of cervical cancer cells by downregulating UBE2S expression, which is commonly overexpressed in malignant cancers [166].

Some studies have reported that Que inhibits HeLa cell proliferation by

arresting the cell cycle in the G2/M phase. Additionally, it induces apoptosis by

disrupting the mitochondrial membrane potential and activating the intrinsic

apoptosis pathway through the induction of p53 [167, 168]. In this way, Que

reduces the expression of global O-GlcNAcylation, and by reducing O-GlcNAcylation

of AMPK, it increases AMPK activation. It has also been reported that Que

regulates sterol regulatory element binding protein 1 (SREBP-1) and its transcriptional targets. Que treatment reduces O-GlcNAc transferase (OGT)

reactivity and downregulates SREBP-1 in HeLa cells [169]. Treatment of Que in

HeLa cells resulted in varying degrees of reduction in cervical cancer cell

survival. Induction of the tumor ERS pathway increased the apoptosis in HeLa

cells. These effects vary on the time- and concentration of Que applied [170].

Also, Que and quercetin-3-O-rhamnoside compounds have been shown to have

cytotoxic effects on HeLa cervical cancer cells. This effect was exhibited by the

inhibition of cell proliferation and migration inhibition of HeLa cells [171].

Ferreira et al. [172] with HMW chitosan/SBE-

Gao et al. [132] encapsulated Que in biodegradable monomethoxy poly

(ethylene glycol)-poly(

Investigating the regulatory mechanisms of Que, for treating cervical cancer, has been demonstrated to be effective in preventing the growth of cervical cancer cells. The survey identified 74 differentially expressed genes (DEGs) by utilizing the GEO database and RNA-seq. Among the five therapeutic candidate genes, which included EGFR, JUN, AR, CD44, and MUC1, they identified 10 miRNAs, 1 lncRNA, and 71 circRNAs. The lncRNA/circRNA-miRNA-mRNA pathway has been constructed to form a regulatory network [17].

Furthermore, Que increases p53 activity, inhibits NF-

Also, in the study of Chakerzehi et al. [174], treatment of HeLa cells with Que (20 µM and 40 µM) for 12 h demonstrated a reduction in the expression of Rac1, a marker of metastasis in cervical cancer cells. Teekaraman et al. [175] confirmed the induction of apoptosis in ovarian metastatic cancer cells and inhibition of their growth under laboratory conditions with 50 and 75 µM Que.

Cui et al. [156], using the immunocytochemical method on human cervical cancer cell lines SiHa, C33A, HeLa, CasKi, and HT-3, determined that the expression of Slug, a tumor suppressor, is decreased in cervical cancer. Twist is involved in the metastasis of cervical cancer [176]. In addition, one study suggested that Que, as a potential therapeutic agent for mitigating coronavirus function, enhances survival in cervical cancer patients by interacting with the primary protease [177]. Generally, Que affects biological processes in cervical cancer related to positive regulation of gene expression, response to drugs, positive regulation of translation, and DNA-template, among others. [178].

Que has been shown to reduce cisplatin drug resistance in HeLa and SiHa uterine cancer cell lines through dose and time-dependent mechanisms [179, 180]. After examining the effect of Que on cell viability when combined with cisplatin, paclitaxel, 5-fluorouracil, and doxorubicin, Xu et al. [179] showed that the combination of Que and cisplatin had a greater impact on cell proliferation compared to their individual effects. Additionally, co-treatment was shown to have a greater effect on cell migration and invasion compared to single-drug treatments, and it also increased cell apoptosis [179]. Also, the results of the study by Ji et al. [180] indicated that the effects of Que and cisplatin on cervical cancer involve mechanisms related to platinum drug resistance and pathways involving p53 and HIF-1. They demonstrated downregulation of the expression of proteins EGFR, MYC, CCND1, and ORBB2 in HeLa and SiHa cells, and regulation of caspase-8 expression.

PEGylated liposomal Que (Lipo-Que) and its antitumor activity were evaluated in vivo and in vitro in human ovarian cancer models with sensitivity (A2780s) and resistance (A2780cp) to cisplatin. In vitro, Lipo-Que has been demonstrated to inhibit cell proliferation, induce apoptosis, and cause cell cycle arrest in A2780s and A2780cp cells. Lipo-Que’s antitumor activity was found to be significantly suppressed in human ovarian tumor xenograft models. According to their conclusion, LipoQue induces cell death, decreases microvessel density, and inhibits tumor growth in both A2780s and A2780cp models [181].

The most important use of Que in combination with other drugs is to reduce the cardiotoxic effect of chemotherapy drugs, thereby increasing the effectiveness of other drugs such as doxorubicin [182]. A study of the effects of Que function on replication and apoptosis of the SKOV-3 ovarian cancer cells showed that Que suppresses the replication of SKOV-3 ovarian cancer cells in a time- and dose-dependent way. Furthermore, Que was shown to promote apoptosis of SKOV-3 cells and to reduce Survivin protein expression. It was also shown to cause SKOV-3 cell cycle arrest in G0/G1 and a significant decrease in the speed of cells in the G2/M phase [183].

In a study investigating the effect of graphene oxide polyvinylpyrrolidone-quercetin-gefitinib (GO-PVP-QSR-GEF) in ovarian cancer cells (PA-1), it was shown that Que inhibited the anticancer properties of gefitinib. Que decreased the viability of PA-1 cells in a dose- and time-dependent manner, with the best effect reported at a dose of 75 µM. Additionally, it has been reported that this effect is mediated through a molecular mechanism involving the promotion of the apoptotic effect of Que in PA-1 cells. Que regulates the intrinsic apoptosis pathway by inhibiting anti-apoptotic molecules such as Bcl-2 and Bcl-xL, while increasing the expression level of pro- apoptotic molecules [144].

In addition to the synergistic effect with chemotherapy drugs for ovarian cancer, Que has also been reported to synergize with radiation therapy in human ovarian tumor xenograft models. Que effectively enhances the effect of radiation-induced cell death. Therefore, combination therapy involving Que with X-irradiation has been advocated to increase DNA damage and apoptotic cell death. Compared to the individual effect of Que or X-rays, their combination leads to an increase in Bax levels and a decrease in Bcl-2 levels in ovarian cancer cell lines (OV2008 and SKOV3). This combination significantly suppresses the growth of tumors through p53-dependent ER stress signals [161]. In a different experiment, Que and selenium were examined for their effect on hydrogen peroxide and ultraviolet (UV) radiation-induced oxidative stress in endometrial adenocarcinoma cells. The study showed that the combined treatment of Que and selenium exhibited synergistic effects as radioprotective and cytoprotective agents. This combination increases cell viability and decreased levels of malondialdehyde (MDA), indicating mitigation of hydrogen peroxide-induced oxidative stress in cells [184].

Given that gynecological cancers are among the leading causes of mortality in women worldwide, it is crucial to implement cost-effective, accessible, and efficient prevention, diagnostic and therapeutic methods in reducing the consequences and burden of these cancers on women’s health. One strategy involves utilizing natural compounds, such as Que, a bioactive polyphenol flavone. Despite the limitations of Que, such as its very poor water solubility, low absorption, rapid metabolism, chemical instability, and rapid systemic removal, it can still be used as a dietary and pharmaceutical supplement either alone or in combination with other drugs for the treatment of gynecological cancers. The use of nanotechnology has the potential to overcome the limitations associated with Que use and envision a new horizon in the treatment of female cancers. In general, Que assists in the prevention, treatment, reduction of drug resistance, and enhancement of the effectiveness of chemical and radiation therapies in gynecological cancers. It achieves these effects through anti-inflammatory, prooxidative, anti-proliferative, induction of apoptosis and cell cycle stop mechanisms. However, to accurately discover the mechanism of action and effectiveness, further human studies are necessary.

The research study was designed by AM, HS, AB, LA and FG, with HS responsible for manuscript writing, and AB, AM, LA and FG contributed to preparing draft and editorial revisions. All authors have reviewed and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. Also, thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research received no external funding.

This research received no external funding.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.