1 Department of Ultrasonic Medicine, West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University, 610041 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

2 Key Laboratory of Birth Defects and Related Diseases of Women and Children (Sichuan University), Ministry of Education, 610041 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, West China Second University Hospital of Sichuan University, 610041 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

Abstract

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) is a condition characterized by severe nausea and vomiting experienced during pregnancy, with an incidence rate estimated to affect between 0.3% and 2% of pregnant individuals. As HG results in prolonged periods of maternal starvation and multiple nutritional deficiencies, it can potentially disrupt the delicate balance of nutrients and metabolic processes required for optimal fetal growth and development. This systematic review aims to analyze the impact of HG on fetal development and birth outcomes.

The following databases were searched from January 2000 to March 2024: PubMed, Web of Science, Science Direct, Medline (Ovid), and Embase (Ovid). The search focused on HG and its pathogenesis, treatment, fetal development, and pregnancy-related adverse outcomes.

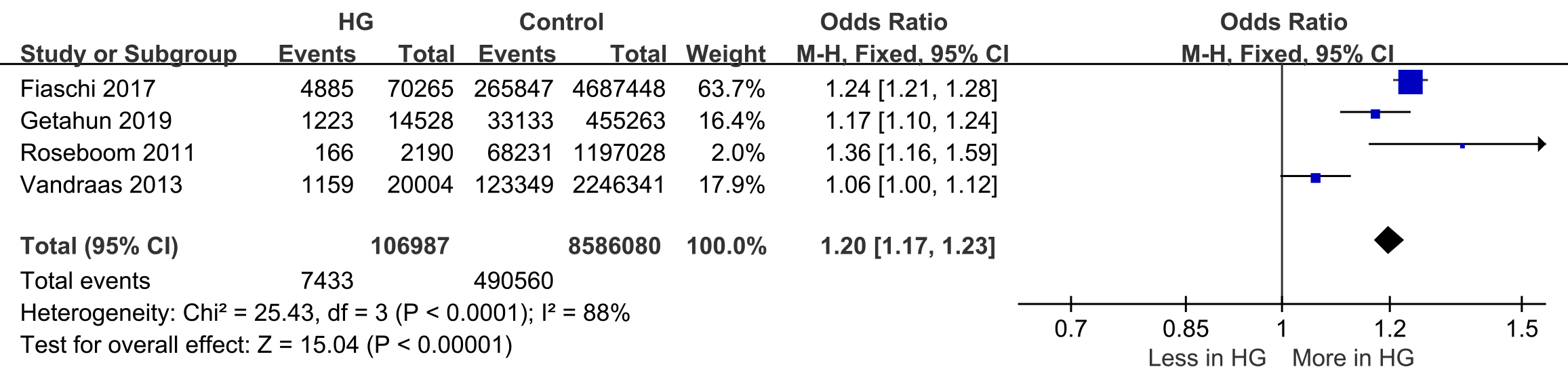

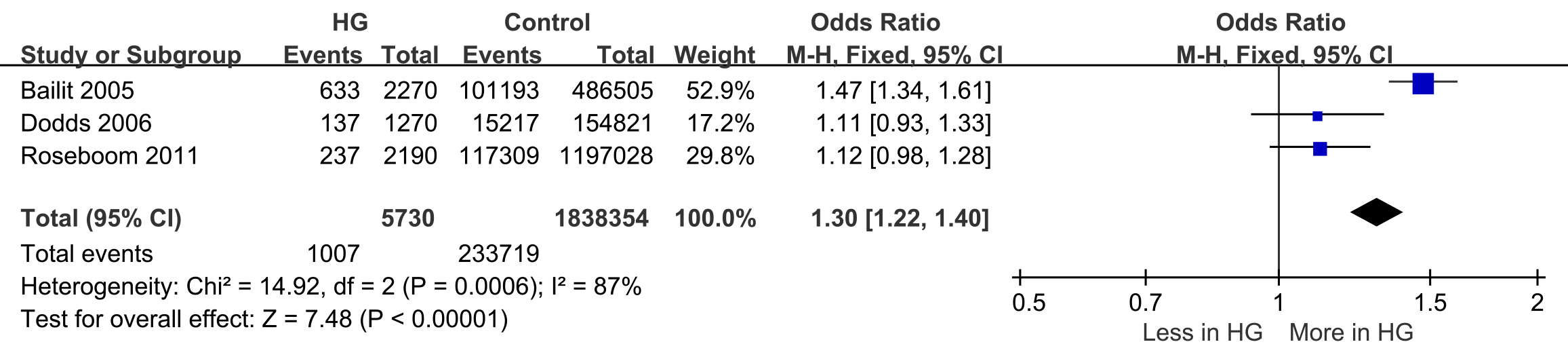

6 out of 907 studies were included which focused on HG with fetal development and birth outcomes. All 6 studies were cohort studies and the quality was high. Meta-analysis revealed that HG is associated with an increased risk of preterm birth (odds ratio (OR): 1.2; 95% confidence interval (95% CI): 1.17–1.23) and small for gestational age (SGA) (OR: 1.30; 95% CI: 1.22–1.40).

A limited number of studies have investigated the effects of HG on fetal development and birth outcomes. The present systematic review indicated an increased risk of preterm birth and SGA associated with HG; however, high heterogeneity among the limited included studies should be noted.

Keywords

- hyperemesis gravidarum

- fetal development

- birth outcomes

- systematic review

Hyperemesis gravidarum (HG) is a severe manifestation of nausea and vomiting in pregnancy, impacting an estimated 0.3–2% of expectant mothers [1, 2]. According to the 2015 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines, the most commonly used diagnostic criteria of HG include exclusion of other causes of persistent vomiting, acute non-subjective starvation (ketonuria), electrolyte imbalance, acid-base imbalance, and weight loss of more than 3 kg or 5% of pre-pregnancy weight [3]. As there is no internationally accepted definition of HG until recently, the distinction between nausea and vomiting in pregnancy and HG remains somewhat equivocate [4]. The updated Windsor criteria for HG delineates that symptoms must onset before 16 weeks of gestation, manifesting as intense nausea and/or vomiting, resulting in an inability to consume food and/or liquids adequately, and significantly impeding daily functioning [5]. HG may persist throughout pregnancy and has the potential to have profound effects on maternal health and well-being [6].

HG is associated with significant physical and psychological morbidity, including weight loss, electrolyte disturbances, dehydration, and increased risk of hospitalization [3, 7]. It can also lead to feelings of depression, anxiety, and social isolation, negatively impacting quality of life [8]. The disease burden of HG is significantly underestimated. In the United States, HG is the predominant reason for hospitalization in the first half of pregnancy and the second most common cause of hospitalization throughout pregnancy after preterm labor [9].

While the maternal consequences of HG have been well-documented, emerging evidence suggests that HG may also have profound implications for fetal development and birth outcomes [10]. As HG results in prolonged periods of maternal starvation and multiple nutritional deficiencies, it can potentially disrupt the delicate balance of nutrients and metabolic processes required for optimal fetal growth and development [11]. Research has indicated that pregnant women diagnosed with HG are susceptible to experiencing early pregnancy weight loss and inadequate pregnancy weight gain, both of which are recognized as independent risk factors for delivering SGA infants [12, 13].

Several studies [11, 12] have established a link between HG and increased risks of adverse birth outcomes, including preterm birth, low birth weight. Moreover, recent research has raised concerns about the potential impact of HG on fetal neurodevelopment [14], with study reporting higher rates of attention deficit disorders and developmental delays in children who were exposed to HG in utero [15]. This systematic review aims to analyze the impact of HG on fetal development and birth outcomes.

This study was previously registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024551371) and followed PRISMA guidelines. A thorough search was conducted across PubMed, Web of Science, Science Direct, Medline (Ovid), and Embase (Ovid) from January 2000 to March 2024, focusing on HG and its pathogenesis, treatment, fetal development, and pregnancy-related adverse outcomes. We used a combination of keywords in our search strategy, such as ‘hyperemesis gravidarum’, ‘severe vomiting of pregnancy’, ‘fetal development’, ‘perinatal effect’, ‘birth outcome’, and ‘pregnancy outcome’. Language limited English.

Only original clinical articles, particularly case-control and cohort studies, are included in this review. Articles such as systematic reviews, meta-analyses, letters to the editor, and comments were excluded. Animal studies were also excluded. For inclusion, only peer-reviewed articles were considered, whether they had been published or were still in press. HG should have been diagnosed by a professional doctor, and self-reported HG cases were excluded. The inclusion criteria focused on studies examining the associations between hyperemesis gravidarum and fetal development and birth outcomes. Unrelated studies and studies without outcomes of interest were excluded.

PRISMA 2020 guidelines were followed when conducting this systematic review [16]. Two authors (DL and KYZ) conducted an independent review of the titles and abstracts of all studies to evaluate their adherence to the inclusion and exclusion criteria outlined for this systematic review. Papers meeting these criteria underwent a comprehensive evaluation and were re-assessed against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any discrepancies were resolved through author discussions. The extracted data from the included articles encompassed the first author’s name, publication year, country of origin, study design, sample size, and outcomes.

We used SGA as the outcome for evaluating fetal development and preterm birth

(

A nine-item Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to assess the quality of the studies, which is a widely recognized tool for evaluating non-randomized studies in meta-analyses [17]. It assesses quality based on three categories: the selection of study groups, the comparison of groups, and the determination of either exposure or outcome. Ratings are based on these criteria, with up to nine stars indicating the highest quality. Studies scoring seven or more stars are deemed high quality, while those scoring less are considered medium or low quality. This systematic assessment enhances the reliability of meta-analysis results. The I2 statistic and Chi-square were used to assess between-study heterogeneity [18].

A fixed-effects model was used in the meta-analysis, and an odds ratio (OR) was

used to measure the effect size. Additionally, a 95% confidence interval (95%

CI) was calculated for the OR. All statistical analyses were performed using

Review Manager software (RevMan, the Cochrane Collaboration, The Nordic

Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark) version 5.4.1 (http://tech.cochrane.org/revman).

p

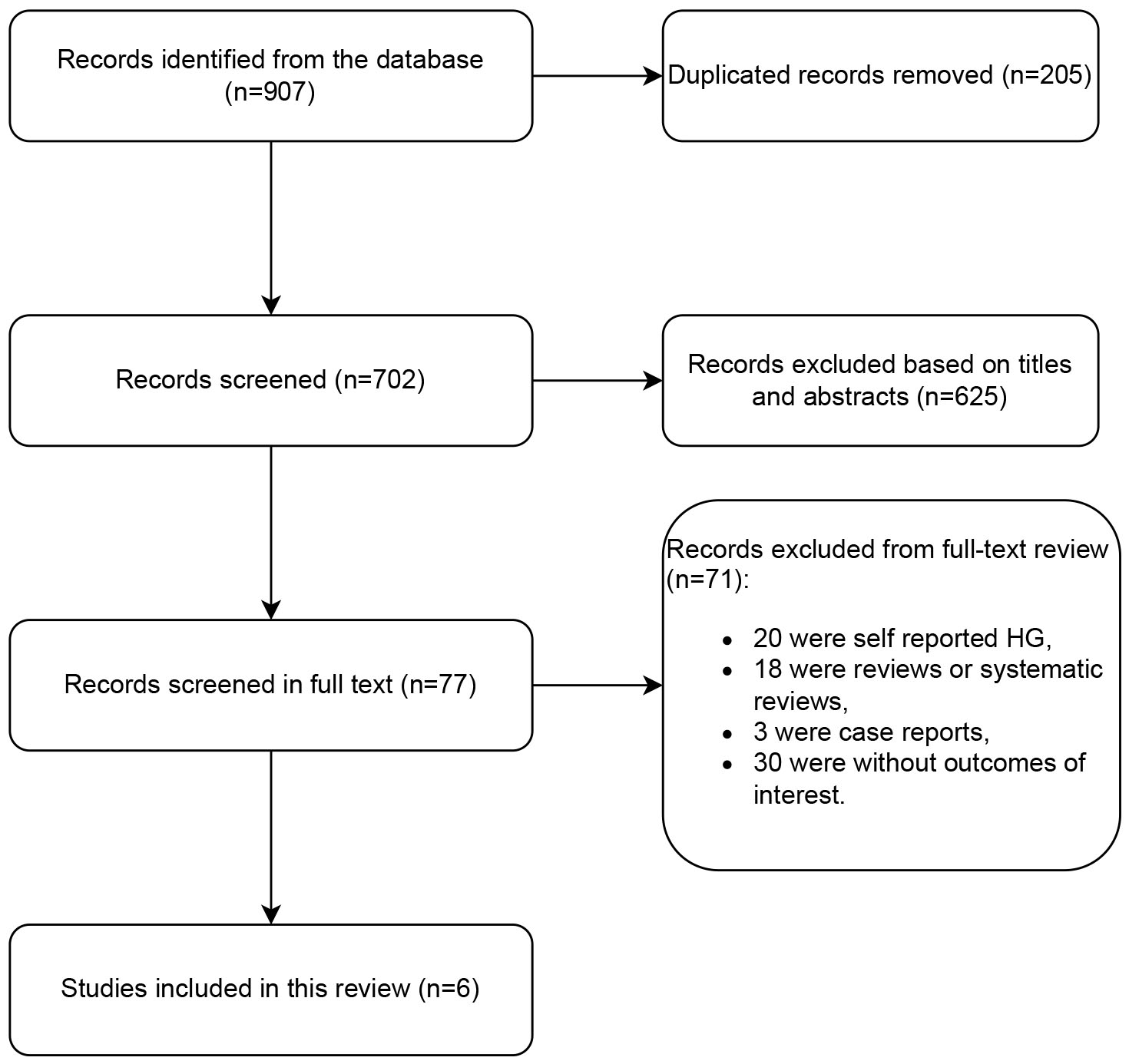

A total of 907 studies were found in the database search. Following a thorough review of the titles and abstracts, a total of 205 duplicate articles and 625 articles deemed irrelevant based on the established inclusion and exclusion criteria were excluded from the study. Of the remaining 77 studies that required a full-text review, 18 were reviews or systematic reviews, 3 were case reports, 20 were self-reported HG, and 30 did not include outcomes of interest were excluded. Finally, 6 studies met the eligibility criteria and were included in the analysis. The flowchart of the study selection process is shown in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram of studies. HG, hyperemesis gravidarum.

In this systematic review, we included 6 studies focused on HG with fetal development and birth outcomes. All 6 studies were cohort studies and were published in English. We provide detailed information on the included papers in Table 1 [19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24]. There were 4 high quality studies and 2 fair quality studies. The quality of included studies were showed in Table 2 [19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24].

| Author | Year | Country | Design | HG case | Total Case | Outcome (n) |

| Fiaschi et al. [19] | 2018 | United Kingdom | Cohort study | 118,197 | 8,211,850 | Preterm birth (4885) |

| Getahun et al. [20] | 2021 | USA | Cohort study | 14,526 | 469,789 | Preterm birth (1223) |

| Roseboom et al. [21] | 2011 | Netherlands | Cohort study | 2190 | 1,199,218 | Preterm birth (166); SGA (237) |

| Vandraas et al. [22] | 2013 | Norway | Cohort study | 814 | 70,654 | Preterm birth (43) |

| Bailit [23] | 2005 | USA | Cohort study | 2466 | 520,739 | SGA (663) |

| Dodds et al. [24] | 2006 | Canada | Cohort study | 1270 | 154,821 | SGA (137) |

SGA, small for gestational age; HG, hyperemesis gravidarum.

| Studies | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Total score | Quality score |

| Fiaschi et al. [19] | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Getahun et al. [20] | *** | *** | 6 | Fair | |

| Roseboom et al. [21] | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Vandraas et al. [22] | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

| Bailit [23] | *** | *** | 6 | Fair | |

| Dodds et al. [24] | *** | ** | *** | 8 | Good |

*, one score.

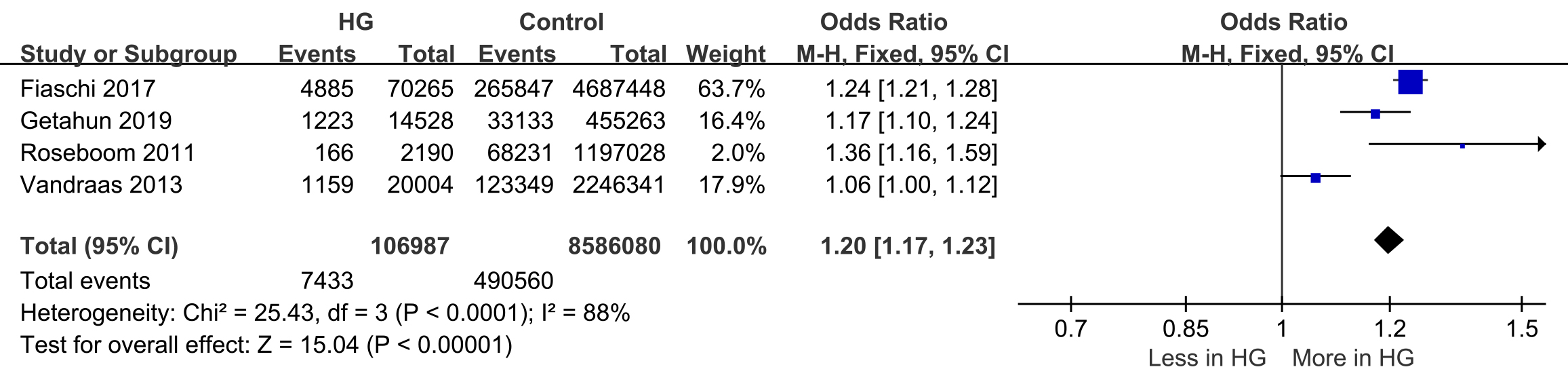

Four studies reported preterm birth

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of preterm birth. 95% CI, 95% confidence interval; M-H, Mantel-Haenszel method.

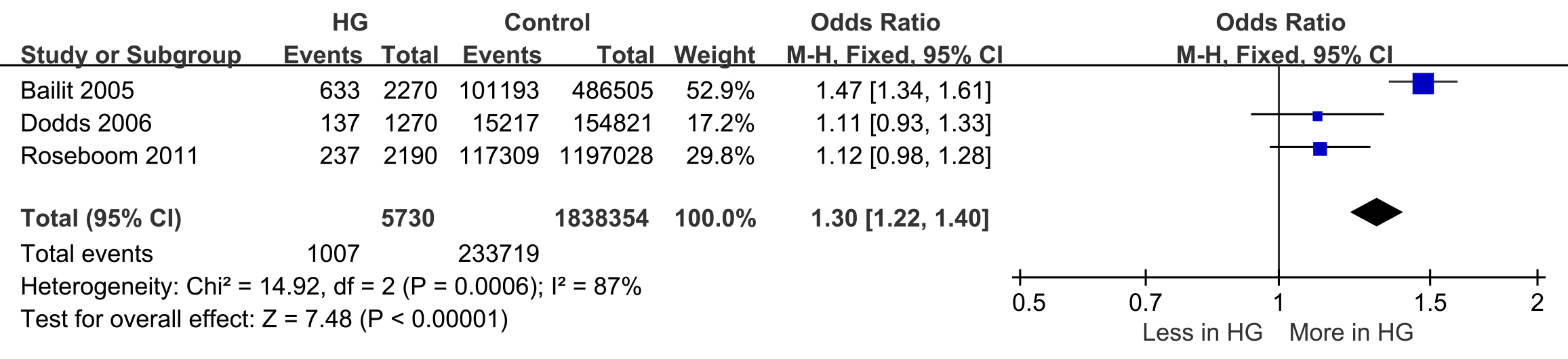

SGA was reported in three studies (events = 1007, n = 233,719) [21, 23, 24]. The likelihood of having an SGA baby was higher in women with HG during pregnancy, with 17.5% of HG pregnancies resulting in SGA babies compared to 12.7% in control pregnancies (OR: 1.30; 95% CI: 1.22–1.40). There was significant heterogeneity in the reported rates of SGA across the studies (I2 = 87%; p = 0.0006) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of small for gestational age (SGA).

This systematic review identified and systematically assessed six studies reporting HG associations with birth outcomes or fetal development. Our findings indicate that HG increases the risk of preterm birth and SGA.

The etiology of HG is multifaceted, with accumulating evidence suggesting that

genetic factors contribute to the susceptibility and severity of this condition.

Research has shown a heightened occurrence of HG in women with a familial

background, suggesting a possible genetic susceptibility. More recently, scholars

have established a correlation between HG and the genes growth differentiation

factor 15 (GDF15) and insulin-like growth factor binding protein 7

(IGFBP7), which are associated with placentation, appetite regulation,

and cachexia [25]. A study involving 543 pregnant women demonstrated that serum

levels of GDF15 and IGFBP7 were significantly elevated in women

with HG at 12 weeks of gestation [26]. Furthermore, higher maternal circulating

levels of GDF15 were linked to an increased risk of developing HG.

Notably, the GDF15 receptor GDNF family receptor

In the present systematic evaluation, we found that pregnant women with HG had a

1.2-fold increased risk of preterm delivery and a 1.3-fold increased risk of

fetal growth restriction compared to normal pregnant women. Similarly, a

meta-analysis including self-reported HG showed that HG is associated with low

birth weight and preterm birth (

Apart from nutritional deficiencies, HG may also adversely affect fetal development through other mechanisms, such as maternal metabolic disorders, electrolyte imbalances, dehydration, and acidosis [35, 36]. Study has found elevated levels of cortisol, parathyroid hormone, and human placental lactogen in the plasma of patients with HG [37], which could potentially impair placental function and fetal development. Although these studies have shed light on the possible mechanisms through which HG may impact perinatal outcomes, the included studies in our review lacked sufficient data on maternal dietary intake, nutritional status, and weight changes during pregnancy.

Prolonged dehydration and electrolyte imbalances, often accompanied by ketonemia and acidosis in HG, can create a suboptimal intrauterine environment for fetal development [14, 38]. Additionally, HG can induce significant physiological stress on the mother, including anxiety and depression, which may influence fetal neurodevelopment and programming through alterations in the maternal hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis [39, 40, 41]. A recent meta-analysis indicated that maternal HG may be linked to slight elevations in negative health outcomes in offspring, such as neurodevelopmental disorders, mental health disorders, and potentially testicular cancer. However, it is important to note that these findings are derived from a restricted number of studies of subpar quality [42].

The management of HG often necessitates a multidisciplinary approach due to its significant impact on maternal well-being and fetal development and birth outcomes. Initially, lifestyle modifications such as consuming small, high-protein, and bland meals are recommended [10]. However, most cases require pharmacological interventions, including antiemetics (vitamin B6, doxylamine), dopamine antagonists (e.g., metoclopramide), serotonin antagonists (e.g., ondansetron), or corticosteroids [43, 44, 45]. In severe cases accompanied by dehydration, electrolyte imbalances, or inadequate oral intake, intravenous fluid therapy and parenteral nutrition may be necessary [46, 47, 48]. Alternative treatments like ginger, acupuncture, and acupressure have been explored, although evidence for their efficacy remains limited [49, 50].

This systematic review encompassed several high-quality studies on the focused

outcome. However, certain limitations warrant consideration. Firstly, some

studies lacked robust control over confounding variables. Secondly, the

measurement of HG severity was inconsistent across studies. Thirdly, high

heterogeneity among the included studies limited our ability to provide aggregate

point estimates, possibly due to variations in HG definitions or reporting of

perinatal outcomes. This issue is further compounded by the fact that the studies

were conducted in diverse countries with different demographic profiles, a known

issue in HG research. Furthermore, our study focuses primarily on SGA and preterm

birth (

This systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrated an association between HG and adverse perinatal outcomes, including preterm birth and SGA. While the underlying mechanisms were not investigated, maternal undernutrition among women with HG is a plausible contributing factor. Future studies should explore the potential role of poor nutritional status in the development of adverse outcomes in pregnancies complicated by HG to elucidate the mechanistic pathways involved.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article.

DL—Project development, Literature Collection, Manuscript writing. KYZ—Project development, Literature Collection, Critical revision of the manuscript, Supervision. Both authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript. Both authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.ceog5109197.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.