1 Department of Endoscopy, Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center; State Key Laboratory of Oncology in South China; Guangdong Provincial Clinical Research Center for Cancer, 510060 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Background: Whole-colon examination is crucial for patients with

gynecologic oncology, which somehow presents challenges in some cases. This study

is aiming to investigate the effectiveness of gastroscope applied in difficult

colonoscopy among such patients. Methods: Patients with gynecologic

oncology who underwent colon examination were assessed and categorized into two

groups, gastroscope replacement group (GR-group) and normal colonoscopy group

(NC-group). Gastroscope was applied in the challenging cases within GR-group

following unsuccessful attempts for colonoscopy. The assessment encompassed

various features, including body mass index (BMI), nutritional indicators,

previous therapeutic history, and the number and size of gynecologic oncology. A

multivariate analysis was performed to screen out high-risk features for

difficult colonoscopy, and a model was developed to evaluate the appropriateness

of gastroscope application in such instances. Decision curve analysis was

conducted to evaluate the clinical usefulness of the model. Results: We

retrospectively collected the clinical characteristics of 171 patients with

gynecologic oncology who underwent colon examinations, with 19 cases and 20 cases

of difficult colonoscopy in GR-group and NC-group, respectively. The success rate

of passing through the narrow site was 63% for the GR-group and 60% for the

NC-group (p = 1.000). High risk factors of difficult colonoscopy included

a BMI

Keywords

- gynecologic oncology

- difficult colonoscopy

- gastroscope

Gynecological oncology accounts for a large proportion of gynecological diseases, mainly including cervical cancer, ovarian cancer and endometrial cancer. Patients with gynecological oncology are often diagnosed with a pelvic mass, which need for a differential diagnosis with other primary tumors [1, 2]. In the case of such patients, it is imperative to conduct a thorough examination of the entire colon. This examination is crucial not only to rule out suspected intestinal invasion, but also to facilitate the selection of appropriate follow-up treatment [3]. Nevertheless, whole-colon examination often presents significant challenges, as the rectosigmoid colon junction is frequently distorted and narrowed due to the compression or invasion of large gynecologic oncology.

Endoscopists, who perform colonoscopy, are well aware that certain cases pose greater challenges than others. Nevertheless, the term “difficult” is highly subjective with its actual definition may vary from endoscopist to endoscopist. In most instances, we define a “difficult colonoscopy” as one where accessing the cecum is challenging or even impossible. However, some may also consider factors such as the duration of the procedure, the amount of physical effort required by the endoscopist, or even the patient’s level of discomfort when assessing the difficulty level [4]. In this study, we defined a “difficult colonoscopy” as patients with gynecologic oncology with colon stenosis, regardless of whether the cecum was palpable by colonoscopy.

In the case of patients facing challenging colonoscopy scenarios, we’ve made a point to turn to gastroscope as a viable solution for completing whole-colon examination, and have demonstrated the feasibility of this approach in many clinical cases. In this study, we aimed at assessing the effectiveness of gastroscope as a substitute for the whole-colon examination, as well as exploring risk factors for difficult colonoscopy in patients with gynecological oncology.

We obtained the approval for this study from the Institutional Review Board of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (approval number: SL-B2024-029-01), which informed consent was exempted. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. We retrospectively reviewed the clinical data of patients with gynecologic oncology who underwent colon examination at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center between January 2021 and December 2023. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (1) aged over 18 years, (2) with a symptom of pelvic mass, (3) clinical diagnosis of gynecologic oncology with radio-graphic confirmation (including computed tomography, or magnetic resonance imaging), (4) completion of at least one colonoscopy. Patients lacking of complete clinical data were excluded.

Enrolled patients were divided into two groups, the gastroscope replacement group (GR-group) and the normal control group (NC-group). In the GR-group, all patients underwent colon examination by gastroscope following unsuccessful attempts with conventional colonoscopy. Conversely, for individuals in the NC-group, colonoscopy was employed for the examination, regardless of unsuccessful cecal intubation.

Meanwhile, in the process of establishing the model for evaluating the suitability of gastroscope application in difficult colonoscopy, patients enrolled were assigned a random number from 1 to 200 in the order of small to large. We drew patients from each group in a 7:3 ratio, and adopted a randomized division of them into the training group (80%) and the validation group (20%). Clinical data, including body mass index (BMI), total protein (TP), album (ALB), globulin protein (GLB), triglycerides (TG), total cholesterol (TCHO), high-density lipoprotein (HDL), low-density lipoprotein (LDL), haemoglobin (Hb), absolute lymphocytes (LYM#), previous therapeutic history, as well as the location, number and size of gynecologic oncology, were recorded.

A standard video-endoscopic system (EVIS LUCERA ELITE system; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) was used for the colon examination. Patients in the GR-group underwent the examination with high-definition video gastroscope (GIF-HQ290; Olympus), while colonoscope (CF-HQ290I; Olympus) is used for those in the NC-group. Specification parameters of gastroscope and colonoscope used in this study were shown in Table 1.

| Gastroscope | Colonoscope | ||

| GIF-HQ290 | CF-HQ290I | ||

| Insert section | Caliber of tip (mm) | 10.20 | 13.20 |

| C of insertion tube (mm) | 9.90 | 12.80 | |

| Effective length (mm) | 1030 | 1330 | |

| Bending angle | Up | 210° | 180° |

| Down | 90° | 180° | |

| Left | 100° | 160° | |

| Right | 100° | 160° | |

| Full length (mm) | 1350 | 1655 | |

Bowel preparation for all patients was conducted using polyethylene glycole-electrolyte solution [5] on the night before the examination day. All colonoscopy insertions were performed using traditional air insufflation method. All colonoscopies were performed with the patients under conscious sedation by a single experienced endoscopist (LJH), who had performed more than 20,000 colonoscopies.

The time to reach cecum was recorded as the interval between the initial insertion through the anal canal and reaching the cecum, determined by recognition of the appendix orifice and ileocecal valve. The success rate of reaching the cecum was compared between the two groups.

Continuous variables were described using mean and standard deviation (SD),

while categorical variables were expressed as frequencies and percentages.

Welch’s t-test and Chi-square test were conducted to statistically

compare the differences between groups for data fit the normal distribution, and

rank sum test was applied for those not fit the normal distribution. Logistic

regression analysis was performed to identify risk factors associated with

difficult colonoscopy. Multivariate analysis incorporated variables with a

significance level of p

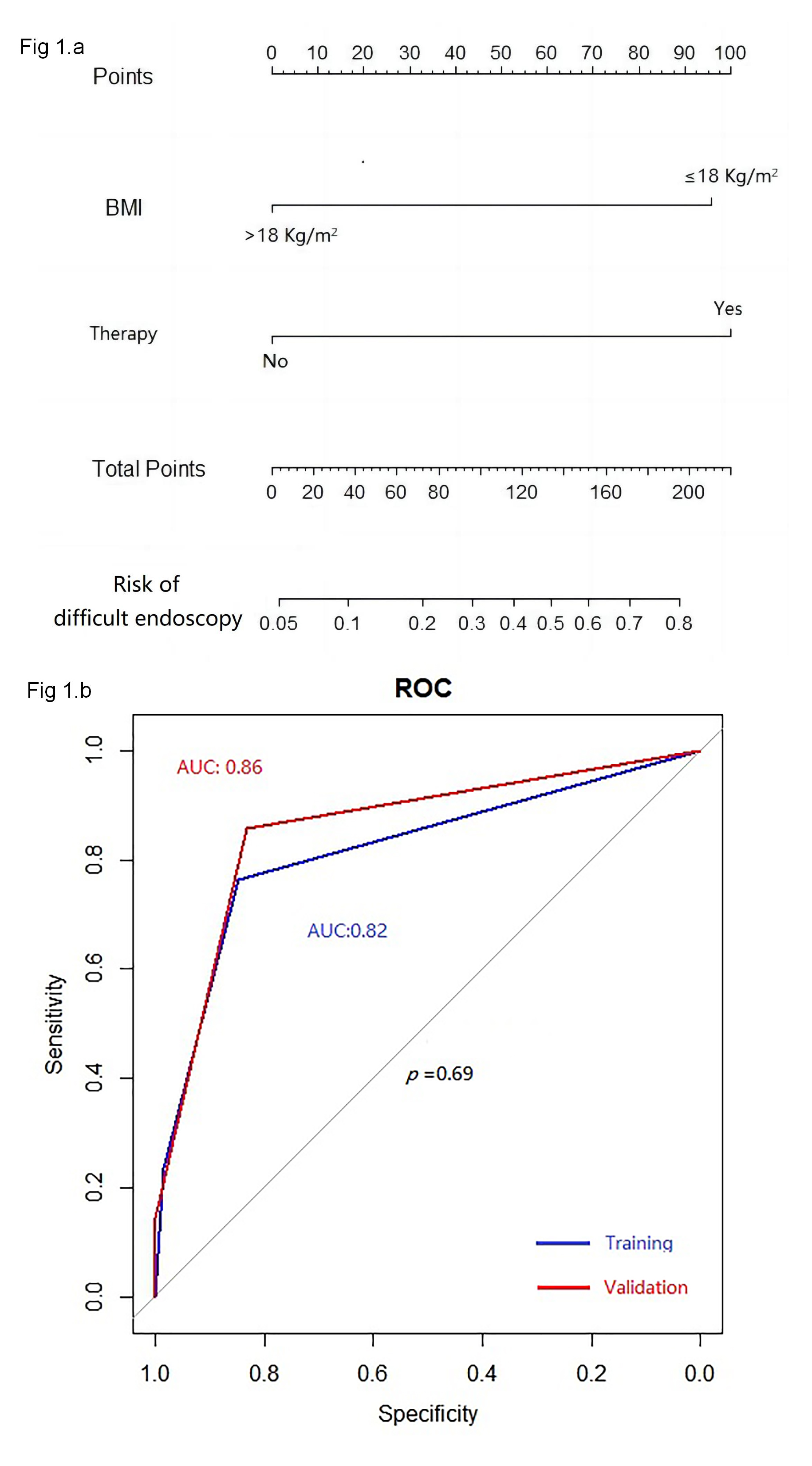

The area under the curve (AUC) of the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was applied to summarized the discriminative ability of the model. An AUC less than 0.5 indicates no discrimination, while an AUC of 1.0 indicates perfect discrimination.

All statistical tests were two-sided, and the significance level was set at 0.05. We conducted statistical analyses using SPSS v24 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). R software (version 4.2.2, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was applied for model development and validation.

Between January 2021 and December 2023, a total of 171 consecutive patients with gynecologic oncology at Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center met the criteria for enrollment. Among the 171 eligible patients, 19 cases were assigned to the GR-group, wherein the colon examination was completed using gastroscope following an unsuccessful attempt at colonoscopy. The rest of them (152 cases) constituted the NC-group, with 20 cases of difficult colonoscopy, as defined above.

The baseline characteristics of the enrolled patients are shown in Table 2.

All the participants were female with gynecologic oncology, which were mainly

ovanrian cancer. There were 42% (8/19) ovanrian cancer patients in the GR-group,

and 84% (128/152) in the NC-group (p

| Index | GR-group (n = 19) | NC-group (n = 152) | p-value | |

| Gender | - | |||

| Femele | 19 | 152 | - | |

| Average age, years | 50.74 |

52.38 |

0.50 | |

| Gynecological malignancy | ||||

| Ovarian cancer | 8 | 128 | - | |

| Non ovarian cancer | 11 | 24 | - | |

| Colon examination | - | |||

| No. of reaching cecum | 12 | 143 | ||

“*”: statistically significant. GR-group, gastroscope replacement group; NC-group, normal colonoscopy group.

Table 3 presented the subgroup analysis between the GR-group and the NC-group in

difficult colonoscopy. Intestinal stenosis was found in all of the 19 patients in

the GR-group, 63% (12/19) of whom successfully passing the narrow site and

finished whole-colon examination using gastroscope. The average time spent to

reach cecum by gastroscope was 15.85

| Index | GR-group (n = 19) | NC-group (n = 20) | p-value |

| No. of passing the narrow site | 12 | 12 | 1.000 |

| Time to reach cecum (min) | 15.85 |

9.02 |

0.080 |

We performed a logistic regression analysis to assess the value of clinical

characteristics in discriminating difficult colonoscopy in patients with

gynecologic oncology. Univariate analysis showed that height less than 150 cm

(p = 0.04, odds ratio (OR) = 7.13, 97.5% confidence interval (97.5%

CI): 1.08–49.72), BMI less than 18 kg/m2 (p

| Characteristics | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||

| OR (97.5% CI) | p-value | OR (97.5% CI) | p-value | ||

| Tumor type | |||||

| Ovarian cancer/non ovarian cancer | 0.29 (0.07–1.10) | 0.08 | - | ||

| Height (cm) | |||||

| 7.13 (1.08–49.72) | 0.04* | 3.66 (0.80–15.76) | 0.08 | ||

| Weight (kg) | |||||

| 2.36 (0.45–18.34) | 0.35 | - | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| 49.13 (4.17–1077.44) | 24.76 (3.19–251.63) | 0.03* | |||

| TP (g/L) | |||||

| 3.98 (0.28–114.95) | 0.34 | - | |||

| ALB (g/L) | |||||

| 1.47 (0.24–13.80) | 0.85 | - | |||

| GLB (g/L) | |||||

| 0.66 (0.69–3.05) | 0.71 | - | |||

| TG (mmol/L) | |||||

| 0.66 (0.69–3.05) | 0.71 | - | |||

| TCHO (mmol/L) | |||||

| 1.37 (1.51–2.17) | 0.68 | - | |||

| HDL (mmol/L) | |||||

| 1.10 (1.25–1.52) | 0.83 | - | |||

| LDL (mmol/L) | |||||

| 0.78 (0.56–1.52) | 0.56 | - | |||

| HGB (g/L) | |||||

| 2.79 (0.16–161.59) | 0.63 | - | |||

| LYM# (×109/L) | |||||

| 0.59 (0.14–2.62) | 0.47 | - | |||

| Therapy | |||||

| Yes/No | 8.02 (2.20–33.58) | 10.17 (3.26–34.94) | |||

| Tumors’ number | |||||

| One/More than one | 4.18 (0.98–22.43) | 0.07 | - | ||

| Maximum diameter of tumor | |||||

| 0.32 (0.08–1.32) | 0.11 | - | |||

Note: “*”: statistically significant. BMI, body mass index; TP, total protein; ALB, album; GLB, globulin protein; TG, triglycerides; TCHO, total cholesterol; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HGB, hemoglobin; LYM#, absolute lymphocytes; OR, odds ratio; 97.5% CI, 97.5% confidence interval.

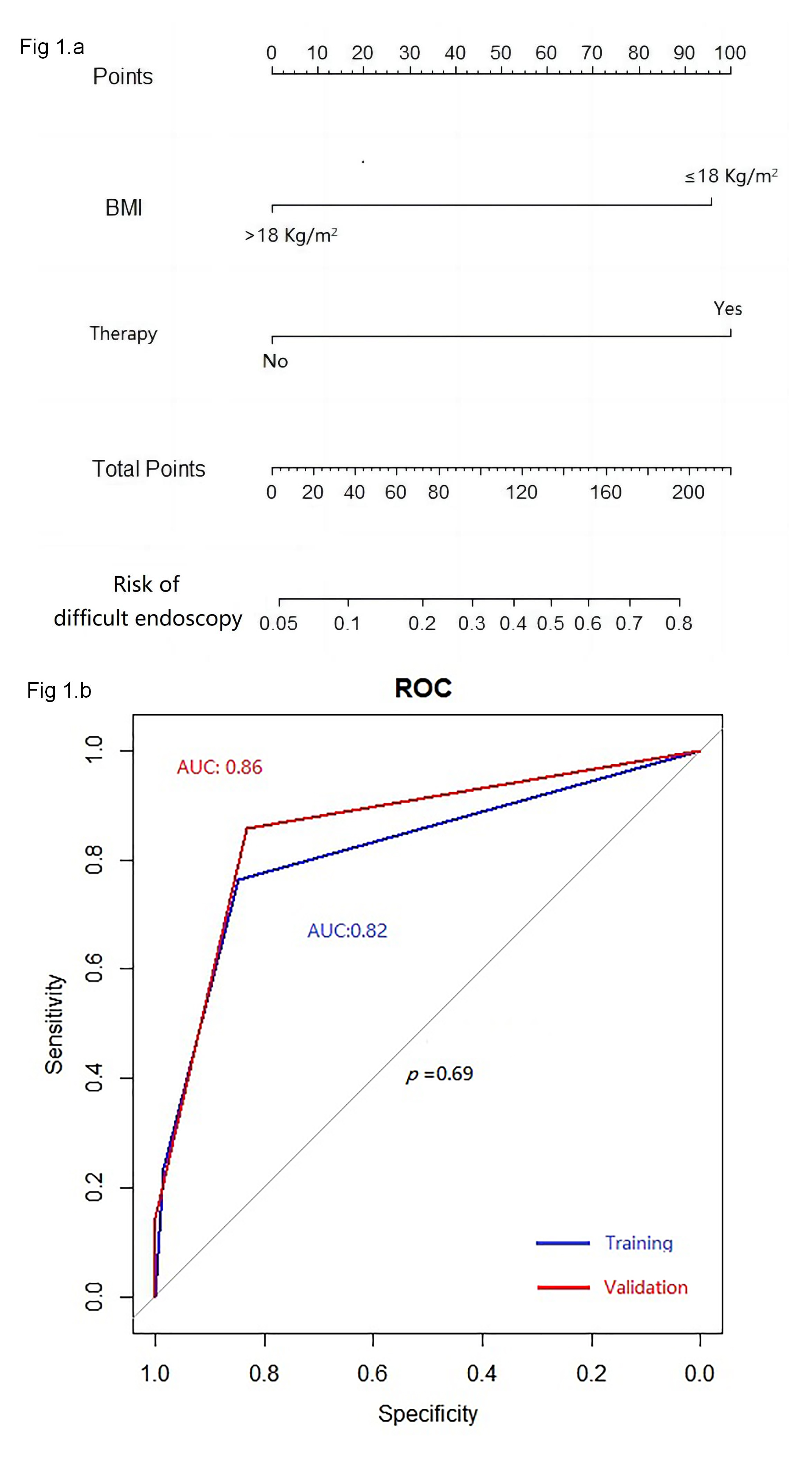

As depicted in Fig. 1a, the aforementioned two independent predictors of difficult colonoscopy in patients with gynecologic oncology were further integrated into an evaluation model for gastroscope replacement. ROC analysis was performed to assess discrimination. The model presented an AUC of 0.82 in the training group and 0.86 in the validation group, respectively (p = 0.69) (Fig. 1b), indicating great discrimination for this model.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The monogram of the model (a); and receiver operating characteristic curves of the model (b). ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

The intestinal tract is the most frequent site of extra-genital invasion for gynecologic oncology, presenting a diagnostic challenge in approximately 30%–40% of patients [6]. This diagnostic complexity often results in significant therapeutic obstacles. Therefore, a thorough examination of the entire colon is extremely important for a comprehensive assessment of the diagnosis and treatment of gynecologic oncology. However, such cases maybe “difficult” in colonoscopy because of stenosis caused by compression or invasion of large gynecologic oncology.

To the best of our knowledge, we have pioneered the comprehensive analysis of the clinical risk factors associated with difficult colonoscopy in patients presenting with gynecologic oncology. Our analysis has identified several significant independent risk factors, including low BMI, and post-treatment status. These findings are significant as they may aid in predicting and managing difficult colonoscopy procedures in this patient population. The association of these above-mentioned variables with difficult colonoscopy could be explained as follows. First, most patients enrolled in our study were female, whose body fat was mainly located at the hips and thighs [7, 8]. A lower BMI means even less abdominal fat content, which causes a poor support for the colon, especially the sigmoid colon, and makes the colonic angle sharper [9, 10]. Second, a sharp angle is frequently observed, primarily at the sigmoid colon, which is easily to become even sharper due to the compression or invasion of the adjacent internal organs. Notably, gynecologic oncology often originated from the ovaries and uterus, which are anatomically adjacent to sigmoid colon. Third, patients who have undergone surgery, radiation or chemotherapy usually exhibit pelvic adhesion, which leads to a sharper angle of the sigmoid colon. This adhesion makes it difficult for the colonoscope to pass through.

Furthermore, we have also proposed the utilization of gastroscope as a potential alternative for the colon examination in patients with gynecologic oncology. A standard gastroscope is much easier to pass through the angulated or fixed narrow sigmoid colon because the caliber of the gastroscope is much smaller than that of a normal colonoscope. As it is reported, the use of a gastroscope is associated with a lower pain score for patients undergoing unsedated colonoscopies. Patients with a very low BMI (less than 22 kg/m2) especially, can benefit from a higher cecal intubation rate [11, 12]. In our study, we proved that gastroscope was not inferior to colonoscopy, and was effective and well-tolerated for patients with gynecologic oncology, in which colonoscopy is difficult. The success rate of cecal intubation was higher than that of colonoscope. Although it took slightly longer time to reach the cecum, there shown no statistically significant differences between gastroscope and colonoscope. The primary reason for the extended duration of gastroscope compared to colonoscope is its shorter insertable length, which necessitates a higher level of endoscopic expertise.

To assess the practicality of gastroscope application in difficult colonoscopy scenarios, we have developed a predictive model based on the identified above-mentioned risk factors. This model exhibits remarkable discrimination and may serve as a valuable tool for selecting the most suitable approach in managing difficult colonoscopy in patients with gynecologic oncology. In the clinical setting, this model facilitates in the prompt identification of patients who would appropriate for gastroscope, thereby preventing delays associated with equipment changes. From an economic perspective, the avoidance of equipment changes translates into cost savings. Additionally, it helps to reduce the duration of anesthesia and enhances patient safety.

The study has the following limitations. As a retrospective study, various types of bias may subjectively exist, such as information bias and selection bias. Additionally, the use of gastroscope instead of colonoscope in this study posed challenges due to the shorter length of gastroscope, which can make the colon examination more difficult. To effectively employ gastroscope in colon examinations, a higher level of endoscopic expertise is required. Furthermore, the sample sizes enrolled in this study are relatively small. Therefore, current findings should be further validated in large-scale prospective studies.

We found that a low BMI and post-treatment status were independent risk factors for difficult colonoscopy in patients with gynecologic oncology. Gastroscope, proven to be an effective and feasible way to help complete the whole-colon examination, can be specially recommended for patients in such cases. Further and larger-scale studies are worth exploring this issue in greater detail.

ALB, album; AUC, area under curve; BMI, body mass index; GLB, globulin protein; GR-group, gastroscope replacement group; Hb, haemoglobin; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; LYM#, absolute lymphocytes; NC-group, normal colonoscopy group; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; SD, standard deviation; TCHO, total cholesterol; TG, triglycerides; TP, total protein.

The data generated in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author.

LNL: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, validation, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing. WQ: data curation, investigation, validation, writing - review & editing. XXH: conceptualization, data curation, investigation, writing - review & editing. YL: conceptualization, methodology, supervision, writing - review & editing. JJL: conceptualization, methodology, project administration, writing - review & editing. WCT: conceptualization, funding acquisition, investigation, project administration, writing - original draft, writing - review & editing. LJH: conceptualization, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing - review & editing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

We obtained the approval for this study from the Institutional Review Board of Sun Yat-sen University Cancer Center (approval number: SL-B2024-029-01), which informed consent was exempted. As a teaching hospital, patients have signed informed consent forms for the use of their clinical data for scientific research before examination. So as a retrospective study, informed consent was exempted by the Institutional Review Board. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This work was supported by the Science and Technology of Guangzhou, China (202201011025), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou, China (2023A04J1779). The funders had no influence on the outcomes of this study.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.