1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Duzce University Medical School, 81620 Duzce, Turkey

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Private Clinic, 55100 Samsun, Turkey

3 Department of Biostatistics, Duzce University Medical School, 81620 Duzce, Turkey

4 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Mediliv Medical Center, 55100 Samsun, Turkey

5 Faculty of Medicine, University of Belgrade, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia

6 Clinic for Gynecology and Obstetrics, University Clinical Center of Serbia, 11000 Belgrade, Serbia

7 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Veris delli Ponti Hospital, 73020 Scorrano, Italy

8 McGill University Health Center Reproductive Center, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, McGill University Health Center, Montréal, QC H4A 3J1, Canada

Abstract

Background: To investigate whether fetal adrenal gland volume (AGV) and fetal zone volume (FZV), important components of the fetal adrenal gland, differ between women who have term and preterm births, and to determine whether these two parameters can be used to predict premature birth. Methods: A total of 238 pregnant women at 24–28 weeks of gestation were included in this case-control study. The fetal AGV and FZV were ultrasonographically evaluated, and corrected AGV (cAGV) and corrected FZV (cFZV) were assessed with adjustments for estimated birth weight. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves were used to assess the ability of AGV, FZV, cAGV, and cFZV to predict preterm birth. Results: Ultrasound exams on 220 term fetuses and 18 preterm fetuses showed that preterm fetuses exhibited higher AGV (p = 0.039), FZV (p = 0.001), cAGV (p = 0.001), and cFVZ (p = 0.001) compared to term fetuses. Conclusions: These results demonstrated that term and preterm fetuses differ in their AGV and FZV within this study population. The data generated by 3D sonography between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation may be beneficial for predicting premature birth. However, larger prospective studies with a larger sample size of preterm births are needed to validate these findings.

Keywords

- fetal adrenal gland

- fetal zone volume

- preterm birth

- 3D ultrasound

Preterm birth is defined as birth that occurs before the 37th week of pregnancy, and its prevalence varies worldwide, ranging from 4% to 16% [1, 2]. More than 13 million babies are born prematurely each year, before the 37th week of pregnancy, which equates to almost 1 in 10 babies being born preterm [3]. Preterm birth and its associated complications are leading causes of death in children under five years old, with nearly 1 million children dying annually as a result of these complications [4]. Many major health issues affect survivors, such as diabetes, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and chronic renal disease [5, 6, 7]. Therefore, the prediction, prompt intervention, and prevention of preterm birth are crucial. Preterm birth is characterized as a syndrome with multiple contributing variables. As a result, there is limited effectiveness in the techniques employed to predict this complex condition. Early hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis activation has received more attention among the variables contributing to preterm birth [8]. Lower progesterone activity and higher concentrations of prostaglandin, protease, and proinflammatory cytokine are known to be higher when the HPA axis is activated early [9]. The development of the adrenal gland, a key element of the HPA axis, occurs in the early stages of embryogenesis. The cortex of the adrenal gland differentiates into the fetal zone (FZ), transitional zone (TZ), and definitive zone (DZ) starting from the 9th week of pregnancy. Of these, the FZ is primarily composed of large cells (20–50 mm) with steroidogenic activity. The size of the entire adrenal gland and the internal FZ in fetuses can significantly increase due to the stressful environment caused by inflammation [10, 11]. Sonographic evaluation of the fetal adrenal gland has revealed that it serves as a marker of placental insufficiency and preterm birth, yet these findings have not been integrated into clinical practice [12, 13]. Another technique for predicting preterm birth is cervical length (CL) measurement, which is now included in all screening programs [14, 15]. CL is measured according to stringent guidelines, with measurements influenced by maternal characteristics, image quality, and the operators’ experience. According to Iams et al. [16], 20% of sonographers who applied for certification were denied on their first attempt. However, preterm birth can be predicted by measuring the fetal adrenal gland, which has a size similar to that of the fetal kidneys from the second trimester onward, and the form and borders of the adrenal can be easily visualized ultrasonographically. The aim of this study was to determine whether the FZ and volumetric measures of the fetal adrenal glands in term and preterm fetuses are suitable for use in clinical settings as indicators of preterm birth.

This case-control study was conducted at the Perinatology Clinic of Duzce University, a tertiary Turkish Medical Center, between March 2019 and March 2021, following approval by the institutional review board (IRB number: 20-1622). Informed consent was obtained from all participants before ultrasonographic examination. Inclusion criteria were as follows: pregnant women attending perinatology clinic for obstetric follow-up; with singleton pregnancies; at 24–28 weeks of gestation; without a history of preterm birth or treatment for preterm birth in their current pregnancies; without amniotic fluid abnormalities (poly- or oligohydramnios); and without intrauterine growth restriction. Exclusion criteria were as follows: hypertension; preeclampsia; diabetes; twin pregnancy; chromosomal or structural abnormalities; active labor; inability to obtain sufficient quality images; inability to given informed consent; and women with M üllerian anomalies.

An Alpinion E-cube 11 (ALPINION Medical Systems, Seoul, South Korea) ultrasound

was used to perform sonography in all patients included in the current study.

Measurements were performed by a single perinatologist (FGG). Prior to measuring

fetal adrenal gland volume (AGV), a fetal biometric assessment with fetal weight

estimation was performed transabdominally in 2D, and CL measurements were

recorded by transvaginal ultrasonography (USG). Patients with CL measurements

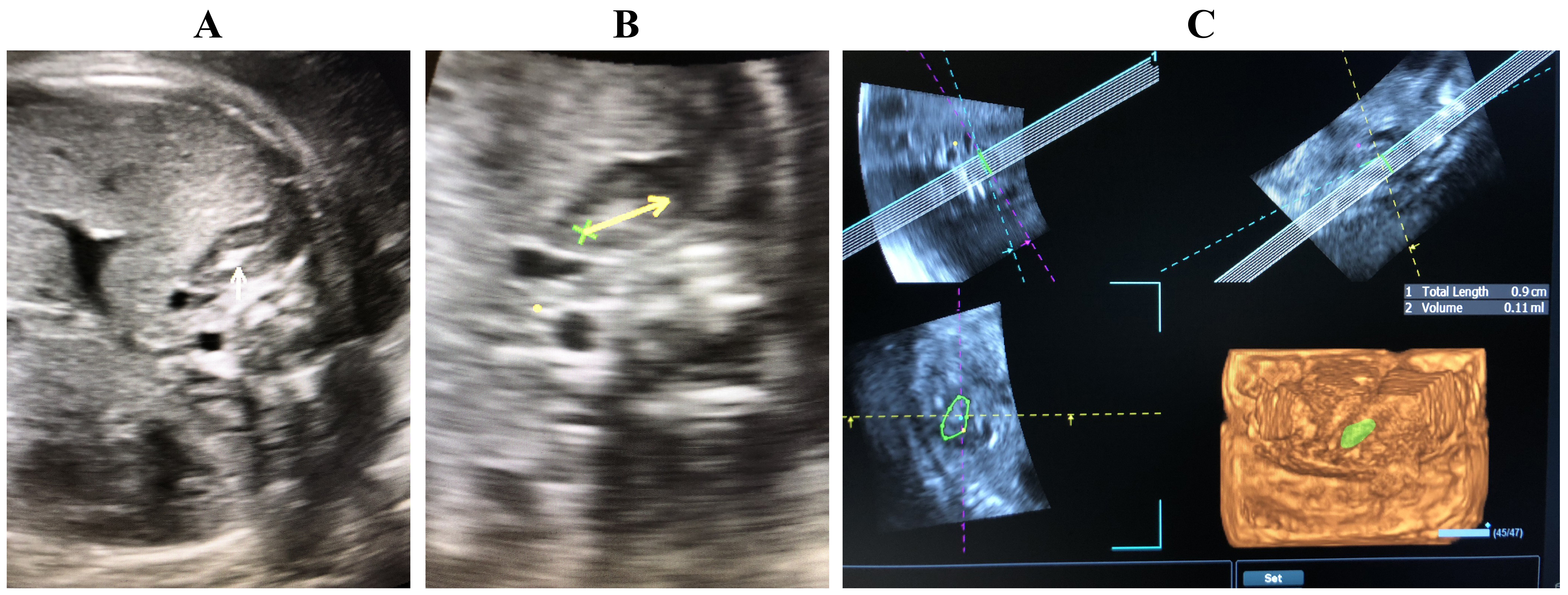

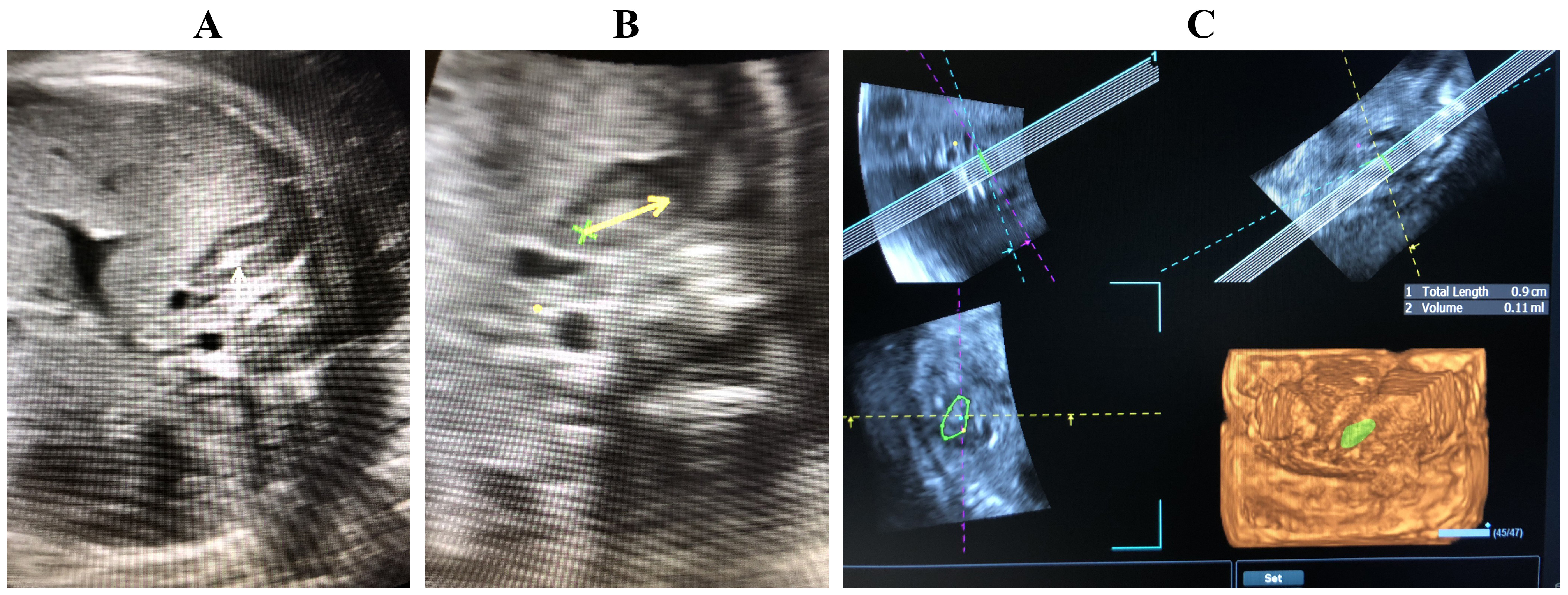

When measuring fetal AGV, the gland closest to the ultrasound probe in the transverse plane was preferred, and only its volume was measured. In cases where a satisfactory image could not be obtained due to fetal position, movements, and/or visual artifacts, patients were scheduled for a second evaluation. Patients from whom no high-quality photos for assessment were obtained were not excluded from the study. During the evaluation of the adrenal gland, the outer hypoechoic area (adrenal cortex) and the inner hyperechoic area (FZ) were identified (Fig. 1). In 3D, both the volume of the adrenal gland and the volume of the FZ were evaluated separately. The corrected AGV (cAGV) and corrected FZ volume (cFZV) were calculated by dividing the obtained volumes by the estimated fetal weight (EFW) at the time of measurement. The Alpinion VOLUME ADVANCETM software (ALPINION Medical Systems, Seoul, Republic of Korea) was used for volumetric calculations.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Volumetric analysis of adrenal gland and FZ. (A) White arrow, adrenal gland and FZ. (B,C) Volumetric measurement of FZ. FZ, fetal zone.

The study collected demographic, follow-up, and delivery data from patients who gave birth at our hospital. The group of patients who had spontaneous preterm births before the 37th week of gestation was compared with the group who had term births after the 37th week of gestation.

Based on previous studies examining preterm birth and fetal AGV [18], to investigate whether the clinical use of FZV as a marker of preterm birth was appropriate, and assuming a 25% increase in FZV with a preterm birth rate of 8%, the required minimum sample size with a power of 80% and a type I error rate of 5% was calculated to be 224.

The distribution of continuous data was analyzed with the Kolmogorov-Smirnov

test, and kurtosis and skewness were also examined. Homogeneity of variance was

examined with the Levene test. Group comparisons for continuous variables were

performed using an independent sample t-test, Welch’s test, or

Mann-Whitney U test depending on whether assumptions were met. Categorical

variables were analyzed with the Pearson Chi-square test or Fisher-Freeman-Halton

test. Descriptive statistics are reported as the mean and standard deviation (SD)

or median, interquartile range, minimum and maximum values for numerical

variables, as appropriate, while frequency and percentage were used for

categorical variables. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was

used to determine the optimal cutoff values for volume parameters in predicting

preterm birth. Statistical analyses were performed with IBM SPSS (Version 22.0,

Released 2013, IBM Corp, IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Armonk, NY, USA). The

significance level was set at p

A total of 238 women were included in the study, with 220 (92.4%) in the term group and 18 in the preterm group. The groups were comparable in terms of age, body mass index (BMI), gestational week at the time of fetal adrenal volume measurement, fetal weight, gravidity, parity, and abortion (Table 1).

| Term (n = 220) | Preterm (n = 18) | p-value | |

| Age (year), mean |

29.04 |

27.67 |

0.287 |

| BMI (kg/m |

28.81 |

27.24 |

0.300 |

| Gestational age at the time of ultrasonography (week), mean |

25.65 |

25.11 |

0.081 |

| Pre-pregnancy weight (kg), mean |

61.38 |

62.56 |

0.899 |

| Fetal weight (g), mean |

889.82 |

824.44 |

0.094 |

| Gravidity, median (IQR) [min–max] | 2 [1–7] | 2 [1–4] | 0.203 |

| Parity, median (IQR) [min–max] | 1 [0–3] | 1 [0–2] | 0.717 |

| Abortion, median (IQR) [min–max] | 0 [0–5] | 0 [0–1] | 0.084 |

| Live, median (IQR) [min–max] | 1 [0–3] | 1 [1–2] | 0.057 |

p: the comparison between term and preterm group was analyzed by independent sample t test.

p

BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation; IQR, interquartile range (75th–25th percentile).

Although the AGV (p = 0.039), FZV (p = 0.001), cAGV

(p

| Term (n = 220) | Preterm (n = 18) | p-value | |

| AGV (mm |

789.32 |

881.81 |

0.039 |

| FZV (mm |

387.64 |

457.83 |

0.001 |

| FZV/AGV, mean |

0.496 |

0.514 |

0.224 |

| cAGV (mm |

0.888 |

1.068 |

|

| cFZV (mm |

0.439 |

0.549 |

|

| CL (mm), mean |

36.78 |

36.06 |

0.619 |

p: the comparison between term and preterm group was analyzed by independent sample t test.

p

AGV, adrenal gland volume; FZV, fetal zone volume; cAGV, corrected adrenal gland volume; cFZV, corrected fetal zone volume; CL, cervical length; SD, standard deviation.

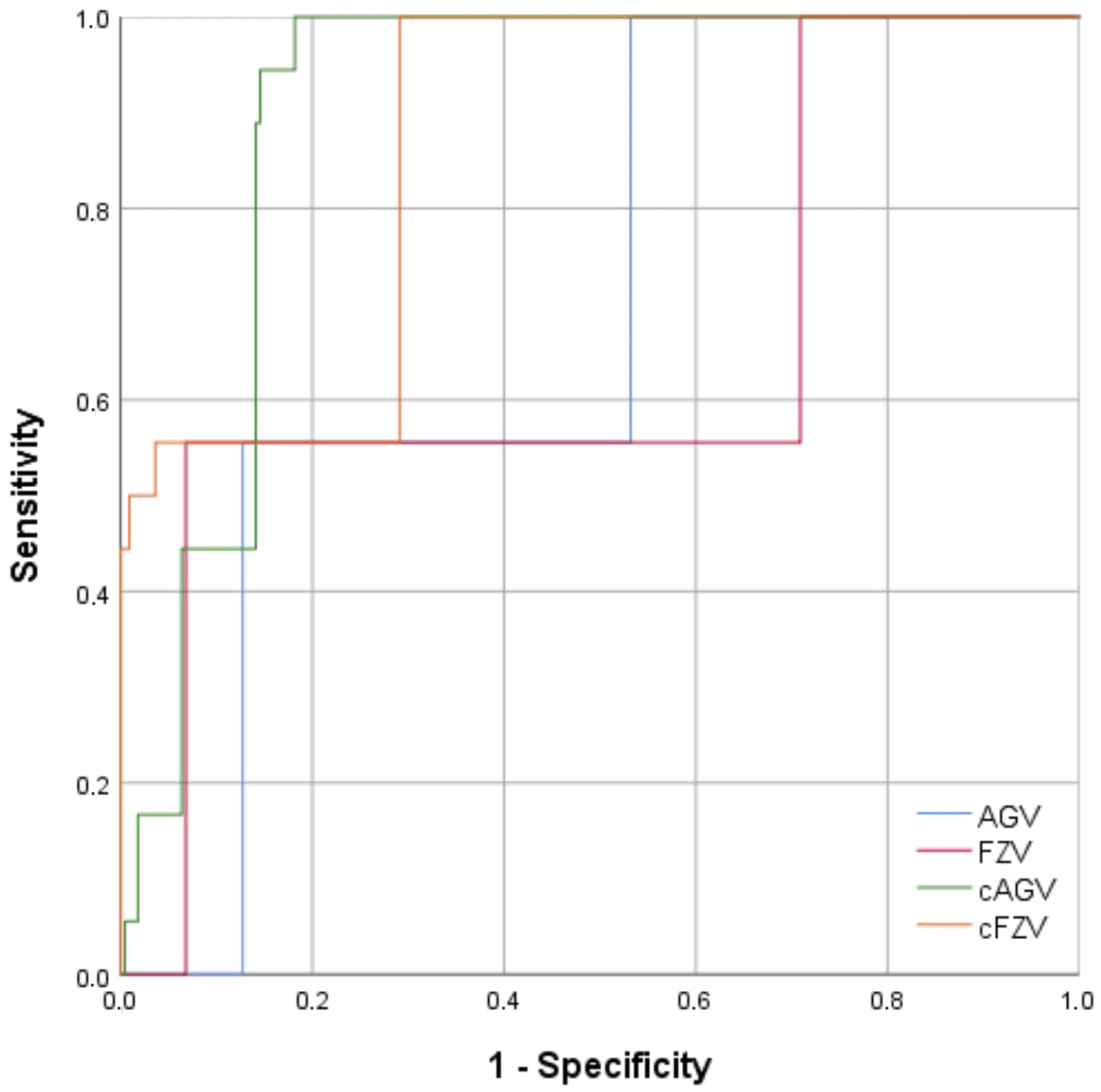

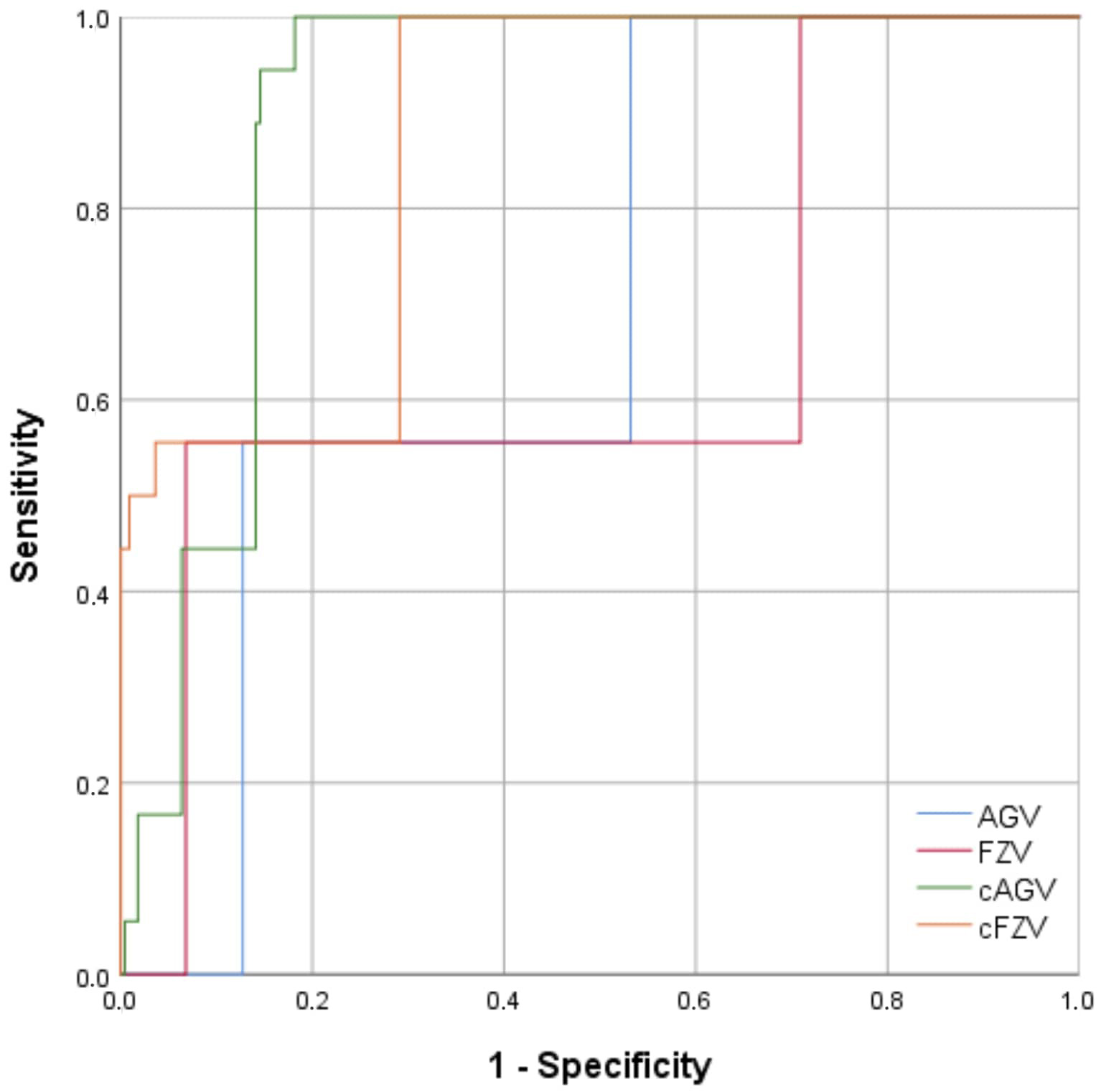

ROC curve analysis revealed that patients with an AGV of

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

ROC curves for AGV, FZV, cAGV, and cFZV in predicting preterm birth. ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AGV, adrenal gland volume; FZV, fetal zone volume; cAGV, corrected adrenal gland volume; cFZV, corrected fetal zone volume.

| AUC | 95% CI | p-value | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity | |

| AGV | 0.693 | 0.590–0.796 | 0.007 | 100 | 46.8 | |

| FZV | 0.647 | 0.496–0.798 | 0.038 | 55.6 | 93.2 | |

| cAGV | 0.899 | 0.858–0.941 | 100 | 81.8 | ||

| cFZV | 0.868 | 0.797–0.940 | 100 | 70.9 |

AUC, area under the curve; CI, confidence interval; ROC, receiver operating characteristic; AGV, adrenal gland volume; FZV, fetal zone volume; cAGV, corrected adrenal gland volume (AGV/estimated fetal weight (EFW)); cFZV, corrected fetal zone volume.

When considering the corrected values, the AUC values for cAGV, and cFZV in

predicting preterm birth were 0.899 and 0.868, respectively. The optimal cutoff

values of cAGV and cFZV for the differentiating preterm birth were

Although not statistically significantly, when a CL of

When the CL was

| CL of |

Term (n = 220) | Preterm (n = 18) | p-value | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| and AGV of |

65 (29.5%) | 12 (66.7%) | 0.001 | 66.7 | 70.5% |

| and FZV of |

15 (6.8%) | 7 (38.9%) | 0.001 | 38.9 | 93.2% |

| and cAGV of |

24 (10.9%) | 12 (66.7%) | 0.001 | 66.7 | 89.1% |

| and cFZV of |

28 (12.7%) | 12 (66.7%) | 0.001 | 66.7 | 87.3% |

AGV, adrenal gland volume; FZV, fetal zone volume; cAGV, corrected adrenal gland volume; cFZV, corrected fetal zone volume.

Considering both length and volume together predicted fewer premature births in

all patients. Therefore, the sensitivity values for all parameters decreased

remarkably, while the specificity values increased. The most significant increase

in specificity was observed for AGV (

This case-control study aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of a simple approach that obstetricians may include into routine practice, either as a supplement to or in combination with existing techniques for predicting preterm birth. The findings demonstrated that two useful markers for predicting preterm birth are elevated AGV and increased volume of the FZ, a significant component of the fetal adrenal gland. Our proposed strategy for predicting preterm birth may not be widely adopted, as most obstetricians in many underdeveloped countries lack the capability to perform 3D sonographic scans, despite the increasing availability of advanced ultrasound technology.

During fetal development, the adrenal gland consists of three regions: the DZ, TZ, and FZ. The FZ exhibits the highest steroidogenic activity among the three adrenal gland zones and secretes significant amounts of dehydroepiandrosterone (DHEA) and DHEA-sulphate. These hormones contribute to the production of placental estrogen, which plays a crucial role in initiating labor.

Turan et al. [20] evaluated AGV in the prediction of preterm birth and reported that increased AGV was associated with preterm birth. In the present study, results showed that the AGV was greater in the preterm birth group. However, when comparing the FZV, where steroidogenic activity was higher, the difference between the term and preterm groups was even more pronounced.

Hoffman et al. [18] found that AGV was lower in the preterm birth group compared to the term birth group when investigating AGV in asymptomatic pregnant women in the third-trimester of pregnancy. Our findings, however, revealed the opposite outcomes. The group with preterm births presented higher FZV and AGV.

Hoffman et al. [12] found that the FZV/AGV ratio did no predict preterm birth. Consistent with this finding, our study also showed that the FZV/AGV ratio was similar in women with term and preterm birth.

Currently, World Association Perinatal Medicine recommends a stepwise approach

for predicting preterm birth. This method can significantly reduce unnecessary

treatments. According to this approach, if the CL

There are many factors that can cause preterm birth. It is still unclear whether alterations in fetal AGV and FZ volume are caused by external variables or if they could initiate a chain of events leading to premature birth. However, Agarwal et al. [22] evaluated women at 28–37 weeks of gestation and reported that both CL measurement and increased FZV are valuable methods that can be used for predicting preterm birth in women at risk.

In the current study, we assessed pregnancies between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation and waited to take another measurement until after the baby was born. As a result, one of the shortcomings of our study was that we did not assess changes in the AGV or FZ volume in pregnant patients after 28 weeks. Other limitations of our study include the possibility for unidentified confounding variables that may have affected the outcome. A further limitation was the small number of patients in the preterm birth group, accounting for only 7.6% of the whole cohort.

Our study only investigates the relationship between AGV and FZV and preterm birth. We found that both are valuable in preterm birth prediction. In our study, we found no significant in CLs between the preterm and term groups at 24–28 weeks, suggesting that AGV and FZV may provide earlier prediction of preterm birth. However, due to the small number of preterm cases in our study, further research with larger cohorts of preterm births is needed to prove this hypothesis.

To the best of our knowledge, no published study has combined fetal AGVs and CL measurements between 24 and 28 weeks for the prediction of preterm birth. The results of our study showed that fetal cAGV and cFZV appeared to be good predictors of preterm birth, whether considered individually or in combination with CL.

The study results indicated that 3D assessment of AGVs between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation, combined with CL measurement, provides a reliable and non-invasive diagnostic tool. This method can be used by obstetricians in daily practice to further investigate cases where there is a risk of premature birth.

The authors of the study are custodians of the data in anonymous form, which can possibly be provided to anyone who makes a motivated and reasoned request.

Conceptualization, AB, BK, SH, RS and AEK; methodology, AB, BK, AEK, SH, RS, AT and MHD; formal analysis, MAS; investigation, AB, BK; data curation, AB, BK, FGG and EY; writing—original draft preparation, AB, BK, AT; writing—review and editing, AB, BK, EY, AEK, RS, AT, SH, FGG, MAS and MHD; visualization, EY, BK; supervision, AT, RS, MHD, MAS, FGG and SH; project administration, AB. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The local Institutional Review Board Statement (Duzce University) approved the study with the following number: 20-1622. The study was conducted by the Declaration of Helsinki. Informed consent was obtained from patients.

Not applicable.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. Michael H. Dahan is serving as Editor-in-Chief and one of the Guest editors of this journal. Andrea Tinelli is serving as one of the Editorial Board members and Guest editors of this journal. We declare that Andrea Tinelli and Michael H. Dahan had no involvement in the peer review of this article and has no access to information regarding its peer review. Full responsibility for the editorial process for this article was delegated to Paolo Ivo Cavoretto and George Daskalakis.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.