1 Department of Ultrasound, Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 610075 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

2 Department of Ultrasound, Sichuan Provincial Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital, 610045 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Background: During the embryonic stage, the inferior vena cava (IVC) is an important conduit for the hepatic vein and ductus venosus to drain into the right atrium. For fetuses with IVC abnormalities, the prognosis may be favorable if the condition is not complicated with other malformations, but would be poor if atrial isomerism coexists. In severe cases, edema, intrauterine fetal death, and atrioventricular block may occur. Therefore, comprehensive prenatal ultrasound that provides detailed information about IVC abnormalities may be clinically significant. Methods: A total of 180 fetuses diagnosed with IVC anomalies via prenatal ultrasound at Hospital of Chengdu University of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Sichuan Provincial Maternity and Child Health Care Hospital from January, 2017 to December, 2022 were included in this study. Their ultrasound image characteristics, associated intra- or extracardiac malformations and pregnancy outcomes were retrospectively analyzed. Results: Among the 180 fetuses, 59 cases were diagnosed with interrupted IVC (53 cases with the interruption of the hepatic segment of the right IVC and 6 cases with the interruption of the entire right IVC), 1 case was diagnosed with the stenosis of the hepatic segment of the right IVC, 90 cases were diagnosed with left sided IVC, 29 cases with double IVC, and 1 case with abnormal connection of the IVC to the left atrium. Moreover, 33 cases had intracardiac malformations and 36 cases had extracardiac malformations. Pregnancy outcomes: 160 fetuses were live born, and their prenatal ultrasound diagnoses were confirmed by computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or surgery; the remaining 20 fetuses were terminated due to serious malformations, and their prenatal ultrasound diagnoses were confirmed by pathologic examination. Conclusions: Prenatal ultrasound can clearly reveal the fetal IVC abnormalities and the associated intra- or extracardiac malformations. For suspected cases, attention should be focused on prenatal ultrasound examinations in order to obtain valuable information for prenatal consultation and subsequent procedures and care.

Keywords

- inferior vena cava abnormality

- prenatal

- ultrasound

- fetus

The inferior vena cava is the largest vein in the human body formed by the confluence of the left and right common iliac veins at the fifth lumbar vertebra (L5) vertebral level. It rises along the right side of the abdominal aorta, passes through the central tendon of the diaphragm into the thoracic cavity, and enters the right atrium of the heart. At the entrance lies the valve of the inferior vena cava, or, the Eustachian valve. The inferior vena cava predominately collects venous blood from the lower limbs, pelvis and abdominal cavity. With the advancement of prenatal ultrasound, the study of the fetal inferior vena cava has become more efficient. Fetal inferior vena cava (IVC) abnormalities mainly include interrupted IVC accompanied by the drainage of the venous blood through the azygous/hemiazygos vein system to the right atrium (including interruption of the hepatic segment of the right IVC and interruption of the entire right IVC), the stenosis of the hepatic segment of the right IVC, left sided IVC, double IVC, and abnormal connection of the IVC to the left atrium.The reported incidence of interrupted IVC is about 0.02%, that of left sided IVC is about 0.1%, and that of double IVC is about 0.3% [1, 2]. Among these anomalies, the stenosis of the hepatic segment of the right IVC and the abnormal connections of the IVC to the left atrium are extremely rare. At present, there have been a number of reports on IVC abnormalities. However, its etiology remains vague. It has been suspected that the interference from certain factors during the embryonic development stage would lead to the failure of anastomosis or secondary closure of the venous system [3]. The types of inferior vena cava anomalies are various and complex. This study retrospectively analyzed the image characteristics, the associated intra- and extracardiac malformations, and the pregnancy outcomes of 180 fetuses diagnosed with IVC anomalies via prenatal ultrasound. Our hope is to improve the understanding of this condition and provide informative prenatal diagnostic support in clinical care.

For this study, a total of 180 fetuses diagnosed with IVC anomalies via prenatal

ultrasound in the Department of Ultrasound at Hospital of Chengdu University of

Traditional Chinese Medicine and Sichuan Provincial Maternity and Child Health

Care Hospital from January, 2017 to December, 2022 were retrospectively analyzed.

The pregnant patients between 20~40 years of age, with an average

of (30

Diagnostic color Doppler ultrasound machines such as GE E8 (GE Healthcare, Milwaukee, WI, USA), Samsung WS80A (Samsung Medison, Seoul, Korea), Philips EPIQ 7 (Philips Medical Systems, Bothell, WA, USA), Mindray Resona8S (Mindray, Shenzhen, Guangdong, China). and a probe with the frequency of 1.0–8.0 MHz were used for transabdominal volumetric ultrasound probe examinations. All fetuses were screened for malformations in a comprehensive and systematic manner. The screening started with observation of the position of the abdominal aorta and the IVC.

For cases with normal positions, i.e., the abdominal aorta lies along the left posterolateral aspect of the vertebral column and the IVC along its right anterolateral aspect, the probe was inched along the entire IVC with careful observation of its inner diameter, course, and vascular anastomosis. For cases with abnormal positions, in addition to the cautious examination of the anomalies, a thorough scan was also performed for any sign of intra- or extracardiac malformations. The final diagnosis was made jointly by two senior radiologists qualified in prenatal diagnosis after separate examinations. All cases were followed up until 1 year after birth.

The image characteristics of fetal IVC anomalies, the associated intra- and extracardiac malformations, and pregnancy outcomes were observed.

SPSS 19.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data analysis, and the categorical data is expressed in rates.

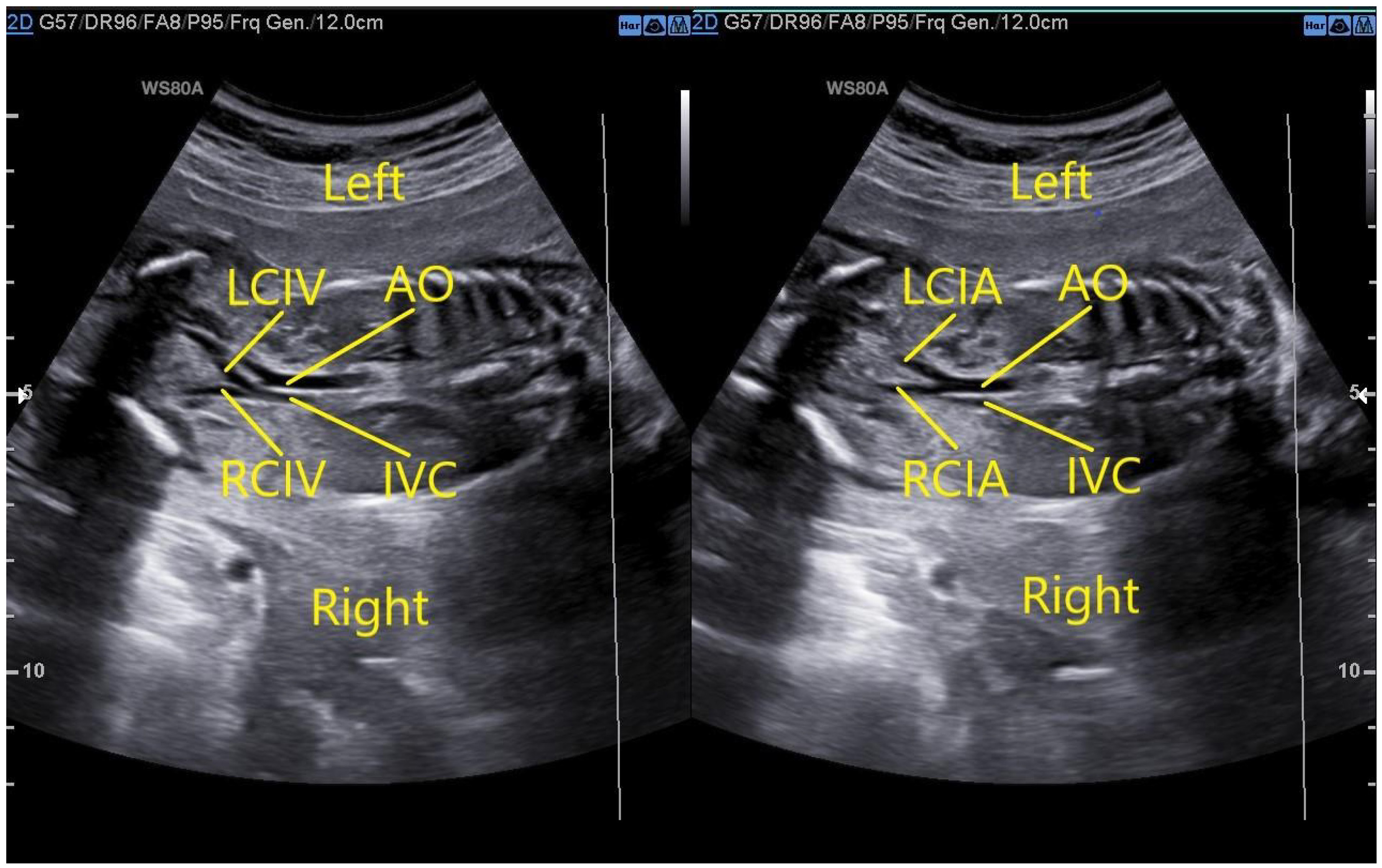

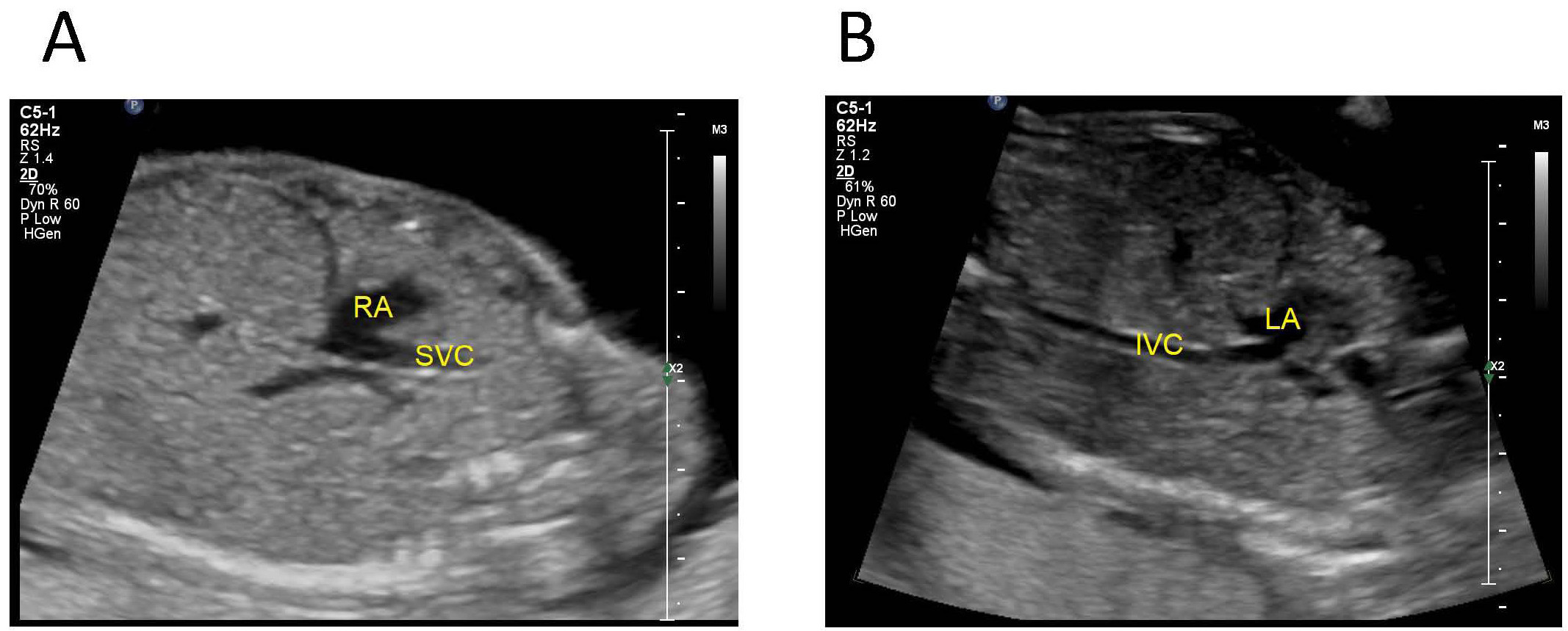

In a fetus with a normal IVC, the oblique coronal view of the thorax and abdomen shows that the left and right common iliac veins merge into the right IVC at the level of the L5 and the abdominal aorta on the left side bifurcates into the left and right common iliac arteries at the lower edge of L4 (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Fetus with normal IVC. The left image demonstrates that the oblique coronal view of the thorax and abdomen would show that the left and right common iliac veins merge into the right IVC at the level of the fifth lumbar vertebra. The right image demonstrates that the abdominal aorta on the left side bifurcates into the left and right common iliac arteries at the lower edge of the fourth lumbar vertebra. AO, abdominal aorta; IVC, inferior vena cava; LCIV, left common iliac veins; RCIV, right common iliac veins; LCIA, left common iliac arteries; RCIA, right common iliac arteries.

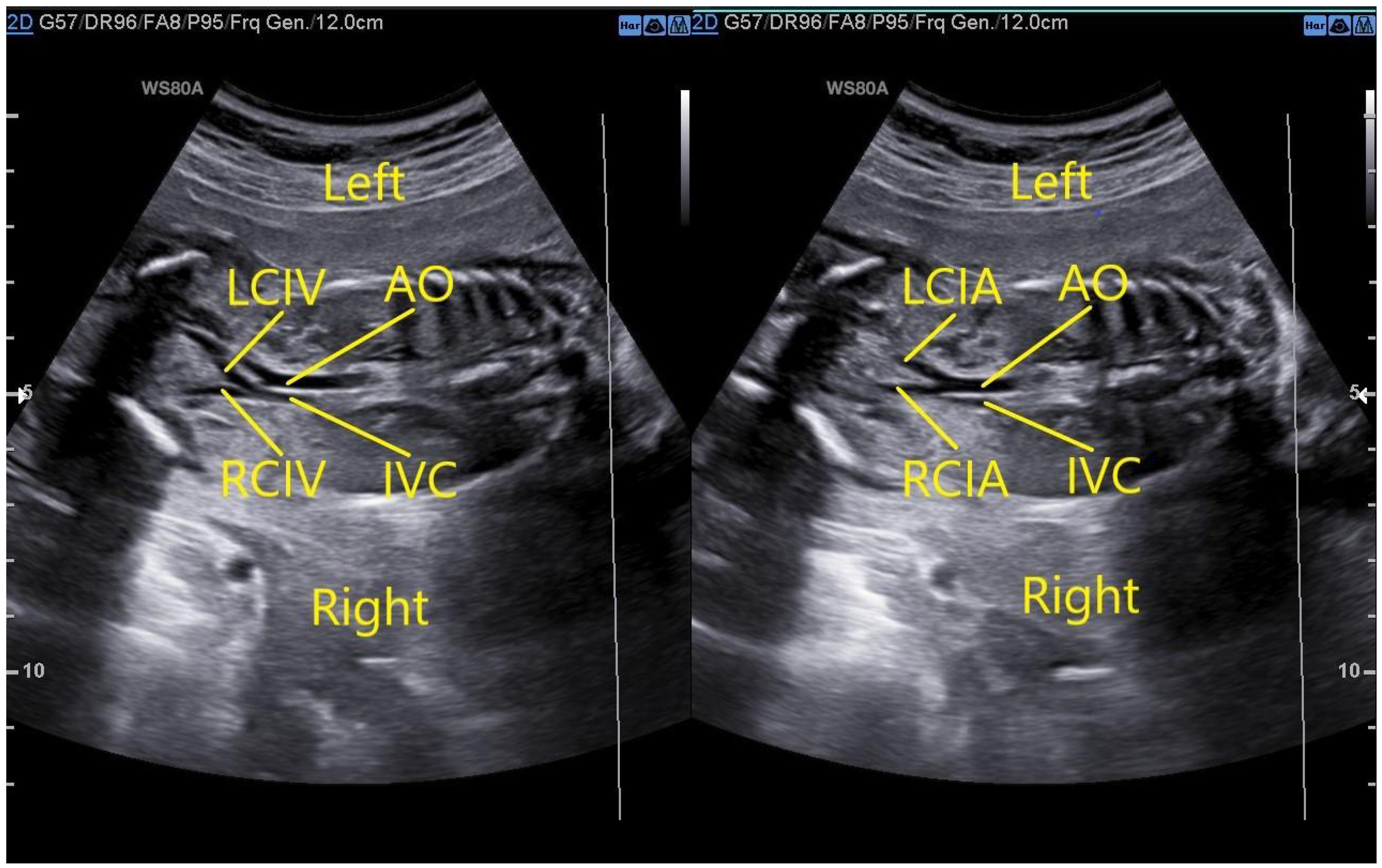

Fetus with interruption of the hepatic segment of the right IVC: both the transverse view of the fetal upper abdomen and the four-chamber view show dilation of the azygos vein, and the oblique coronal view of the fetal thorax and abdomen shows that the IVC connected to the dilated azygos vein at the level of the renal hilum and running along with the abdominal aorta. The venous blood from the lower body returns to the right superior vena cava (SVC) through the azygos vein and then drains into the right atrium (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.Fetus with absence of the hepatic segment of the right IVC. (A) The transverse view of the fetal upper abdomen showing absence of the hepatic segment of IVC and dilation of the azygos vein. (B) The four-chamber view showing dilation of the azygos vein which lies to the right of the descending aorta. (C) The aorta long-axis view showing dilated azygous vein running along the aorta, with blood flow in opposite directions. (D) An oblique coronal view of the thorax showing a dilated azygous vein connected to the superior vena cava and then draining into the right atrium. AO, abdominal aorta; AZ, azygos vein; ST, stomach; SP, spine; UV, umbilical vein; SVC, superior vena cava; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

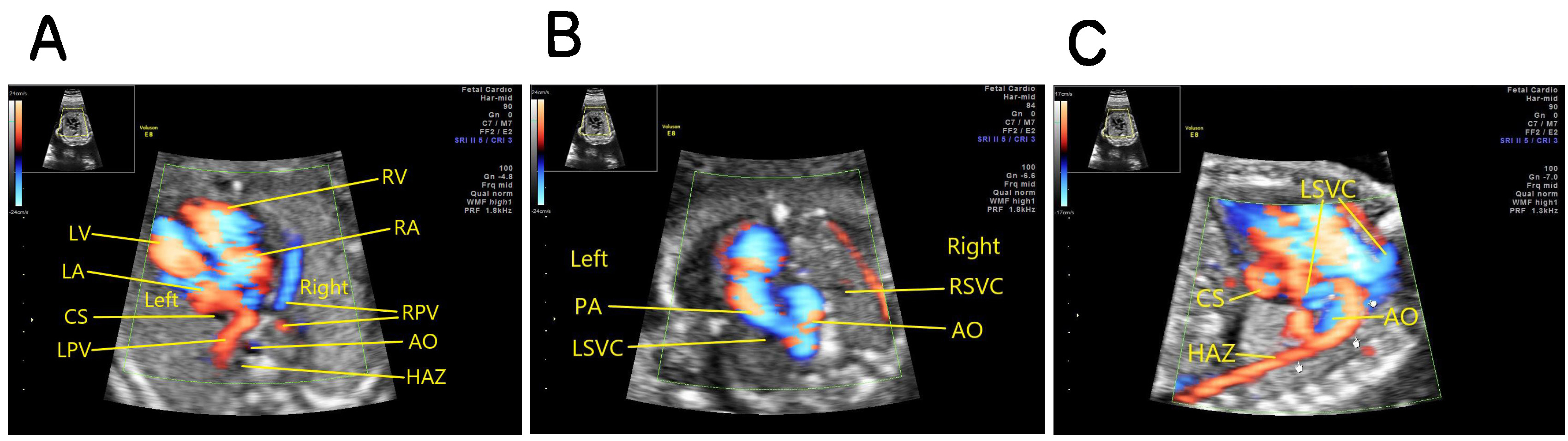

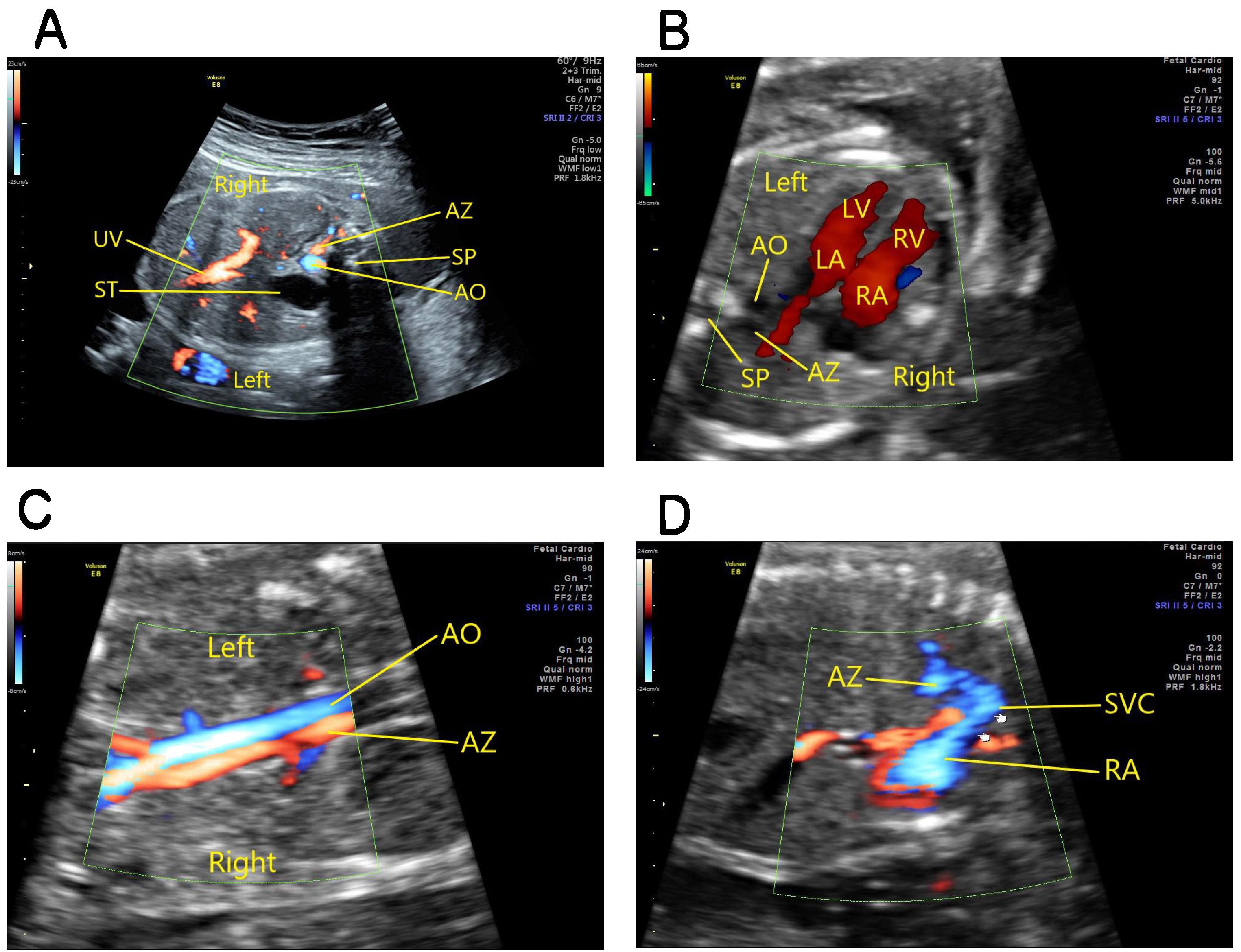

Fetus with interruption of the entire right IVC: the oblique coronal view of the thorax and abdomen showing that the venous blood of the lower body returns to the hemiazygos vein on the left side of the abdominal aorta and then to the permanent left SVC, and then draining into the right atrium through the coronary sinus (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.Fetus with absence of the entire right IVC. (A) Four-chamber view on color doppler showing coronary sinus dilation, absence of inferior vena cava which should be seen in the right anterolateral area of the abdominal aorta, and dilatation of the semi-azygous vein which should be seen in the left anterolateral area of the abdominal aorta. (B) The three vessel and trachea view (3VT view) showing a permanent left superior vena cava on the left side of the pulmonary artery. (C) The oblique coronal view of the thorax and abdomen showing that the venous blood of the lower body returning to the dilated hemiazygos vein on the left side of the abdominal aorta. hemiazygos vein to the permanent left SVC, and then draining into the right atrium through the coronary sinus. AO, abdominal aorta; PA, pulmonary artery; RSVC, right superior vena cava; HAZ, hemiazygos vein; LSVC, left superior vena cava; CS, coronary sinus; LPV, left pulmonary vein; RPV, right pulmonary vein; LA, left atrium; LV, left ventricle; RA, right atrium; RV, right ventricle.

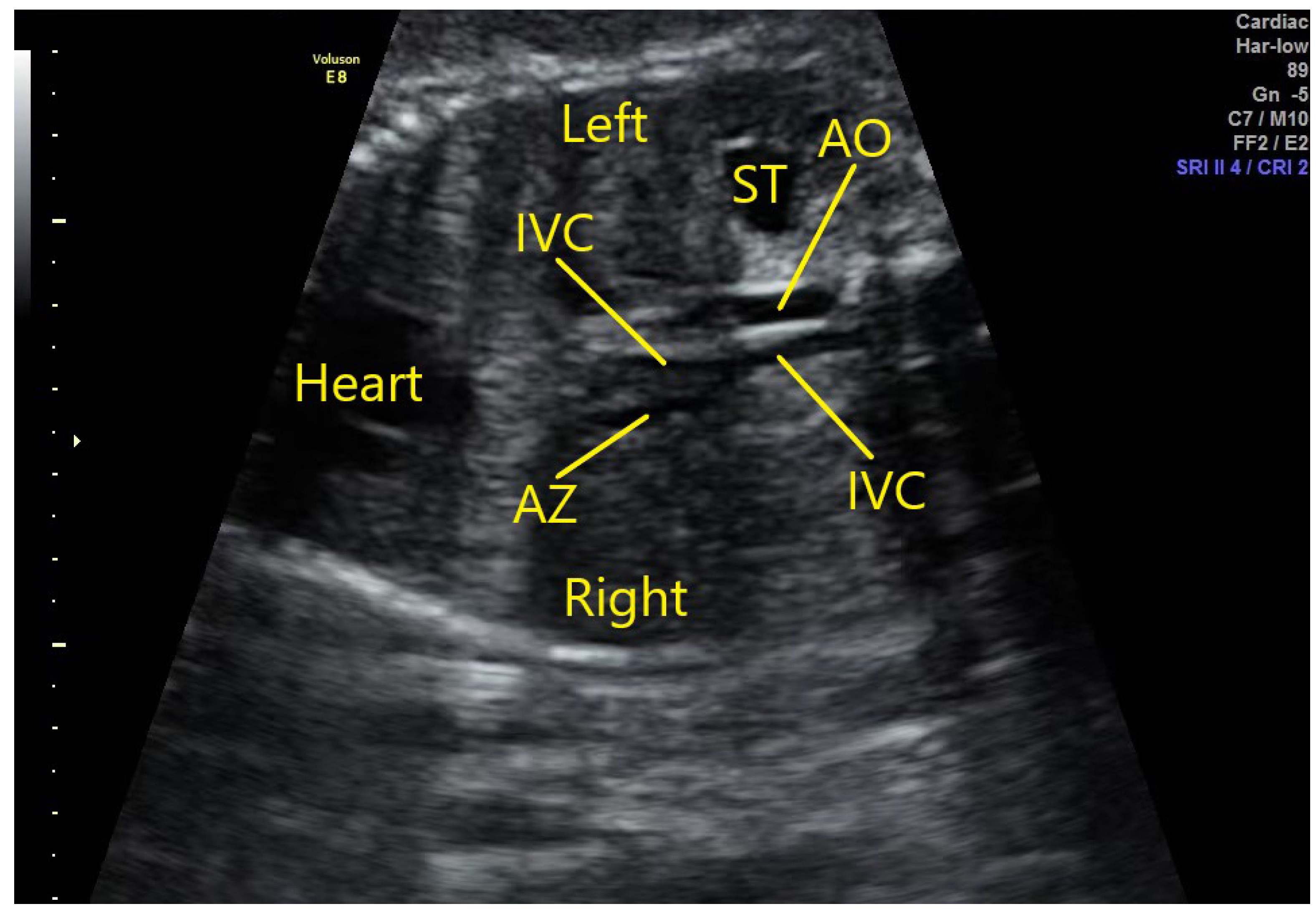

Fetus with the stenosis of the hepatic segment of the right IVC: the oblique coronal view of the fetal thorax and abdomen showing that the returning venous blood from the lower body has two divided ways at the level of the renal hilum. A portion returns to the stenotic hepatic segment of the right IVC and then to the right atrium, and the remainder returns through the dilated azygos vein which then joins the right SVC and then drains to the right atrium (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Fig. 4.Fetus with stenosis of the hepatic segment of the right IVC. The oblique coronal view of the fetal thorax and abdomen demonstrates that the returning venous blood from the lower body has two divided ways at the level of the renal hilum. A portion returns to the stenotic hepatic segment of the right IVC and then to the right atrium, and the remainder returns through the dilated azygos vein which then joins the right SVC and drains to the right atrium. AO, abdominal aorta; AZ, azygos vein; ST, stomach; IVC, inferior vena cava.

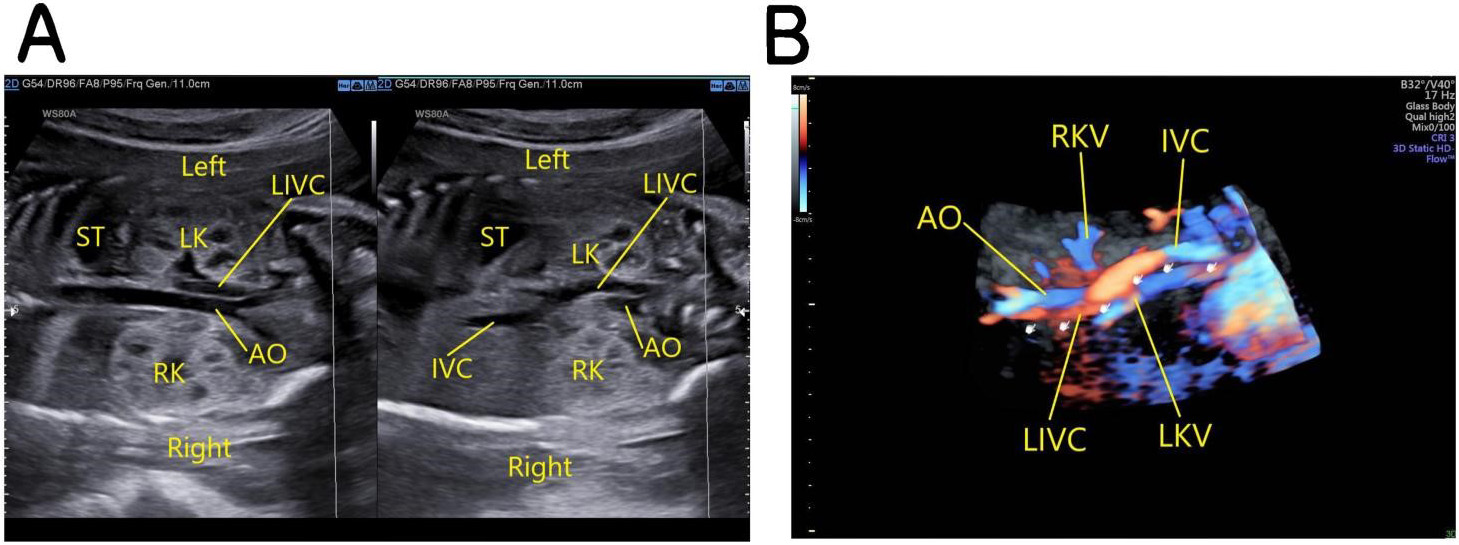

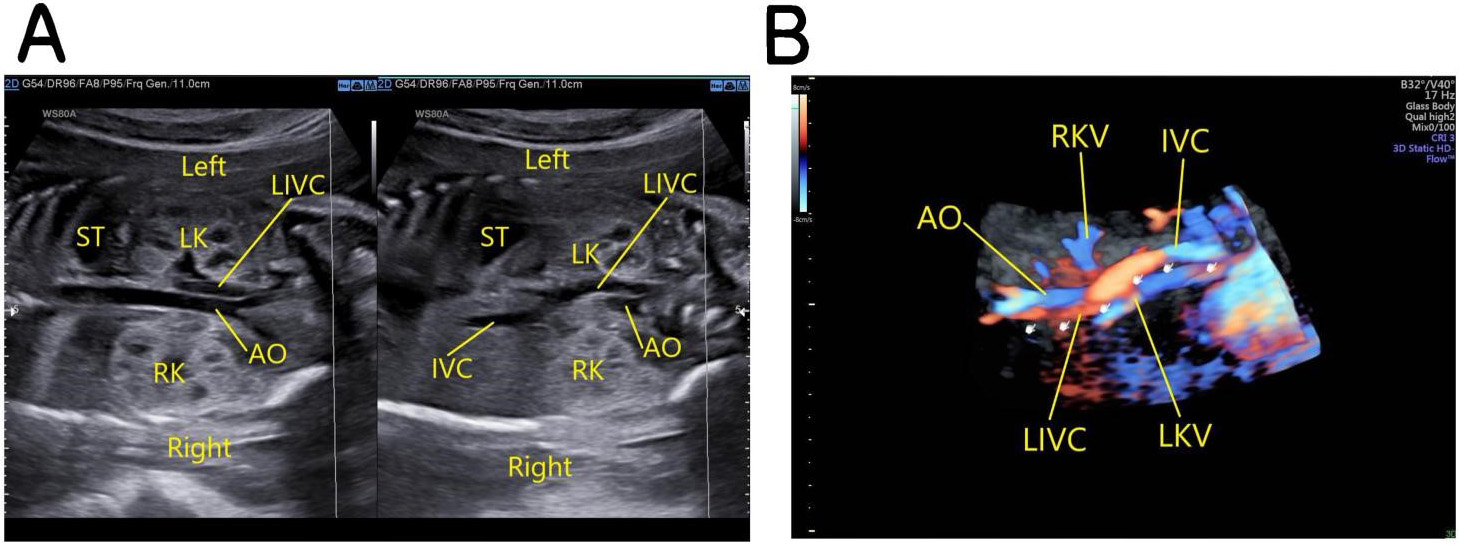

Fetus with left-sided IVC: the oblique coronal view of the fetal thorax and abdomen demonstrates that below the level of the renal hilum the IVC is located on the left posterolateral side of the abdominal aorta and at the level of the renal hilum passes to the front of it and then courses diagonally upwards to the upper right, forming the IVC on the right side and draining into the right atrium (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.Fetus with left-sided IVC. (A) The left image: the oblique coronal view of the fetal thorax and abdomen shows that below the level of the renal hilum the IVC is located on the left posterolateral side of the abdominal aorta. The right image: the left IVC crosses to the front of the abdominal aorta at the level of the renal hilum and then courses diagonally upwards to the upper right, forming the IVC on the right side and draining into the right atrium. (B) 3D Color Doppler images. AO, abdominal aorta; IVC, inferior vena cava; LIVC, left inferior vena cava; ST, stomach; LK, left kidney; RK, right kidney; LKV, left kidney vena; RKV, right kidney vena.

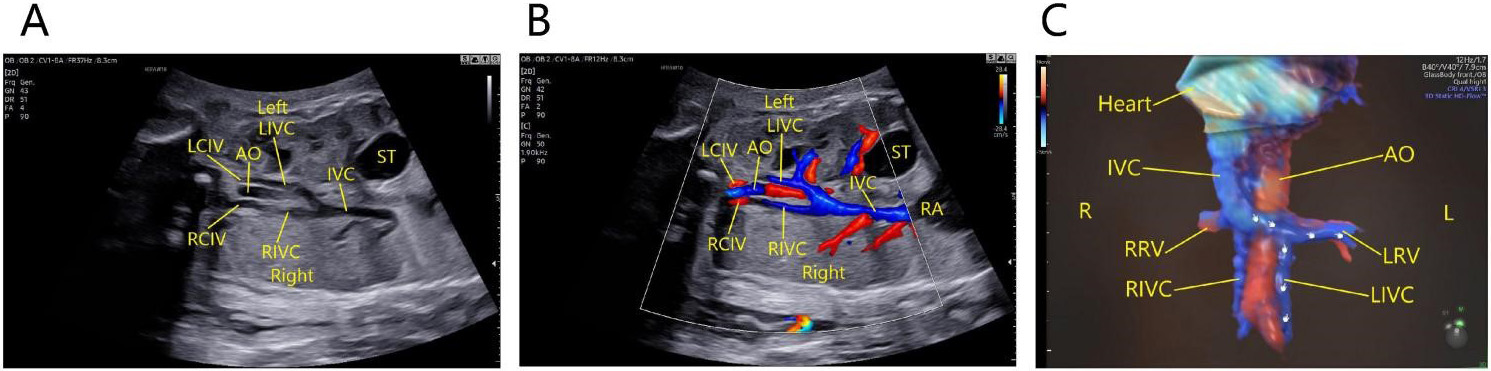

In a fetus with double IVC, there are two types of the condition. Type one: oblique coronal view of the thorax and abdomen shows that the abdominal aorta is accompanied by two inferior vena cavas on both sides. The left iliac vein drains to the left IVC, and the right iliac vein to the right IVC. The left IVC crosses to the front of the abdominal aorta at the level of the renal hilum, and runs obliquely upward to join the right IVC (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Fig. 6.Fetus with double IVC of the first type. The oblique coronal view of the thorax and abdomen shows that the abdominal aorta is accompanied by two inferior vena cavas on both sides. The left iliac vein drains to the left IVC, and the right iliac vein to the right IVC. The left IVC crosses to the front of the abdominal aorta at the level of the renal hilum, and runs obliquely upward to join the right IVC and draining into the right atrium. (A) Two-dimensional ultrasound images. (B) Color Doppler images. (C) 3D Color Doppler images. AO, abdominal aorta; LIVC, left inferior vena cava; RIVC, right inferior vena; cava; LCIV, left common iliac vein; RCIV, right common iliac vein; IVC, inferior vena cava; RA, right atrium; LRV, left renal vein; RRV, right renal vein; ST, stomach; L, Left; R, Right.

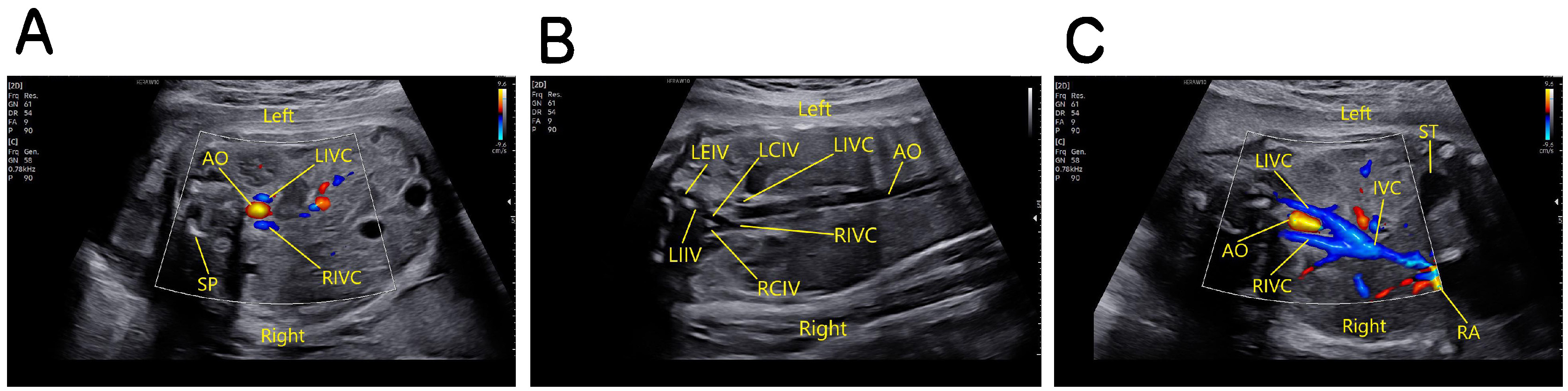

Type two: transverse view of the fetal upper abdomen shows three blood vessels in front of the vertebral column, with the abdominal aorta in the middle and the left and right IVC on either side. The oblique coronal view of the fetal thorax and abdomen shows the left external iliac vein (LEIV) is connected to the left common iliac vein (LCIV), and the right common iliac vein (RCIV) drains into the right IVC, and the left internal iliac vein (LIIV) directly drains into the left IVC which at the level of the renal hilum crosses to the front of the abdominal aorta and runs obliquely upward to the right to join the right IVC (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Fig. 7.Fetus with double IVC of the second type. (A) The transverse view of the fetal upper abdomen shows three blood vessels in front of the vertebral column, with the abdominal aorta in the middle and the left and right IVC on either side. (B) The oblique coronal view of the fetal thorax and abdomen shows the left external iliac vein is connected to the left common iliac vein, and the right common iliac vein drains into the right IVC, and the left internal iliac vein directly drains into the left IVC. (C) The oblique coronal view of the fetal thorax and abdomen shows at the level of the renal hilum the left IVC crosses to the front of the abdominal aorta and runs obliquely upward to the right to join the right IVC and drains into the right atrium. SP, spine; AO, abdominal aorta; LIVC, left inferior vena cava; RIVC, right inferior vena cava; IVC, inferior vena cava; RA, right atrium; LEIV, left external iliac vein; LIIV, left internal iliac vein; LCIV, left common iliac vein; RCIV, right common iliac vein; ST, stomach.

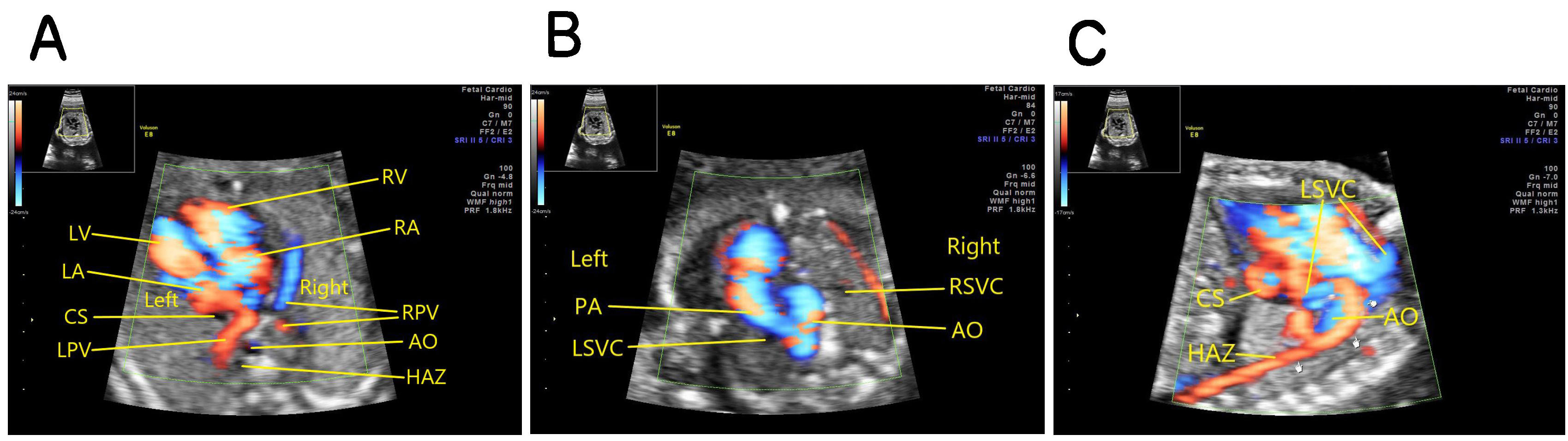

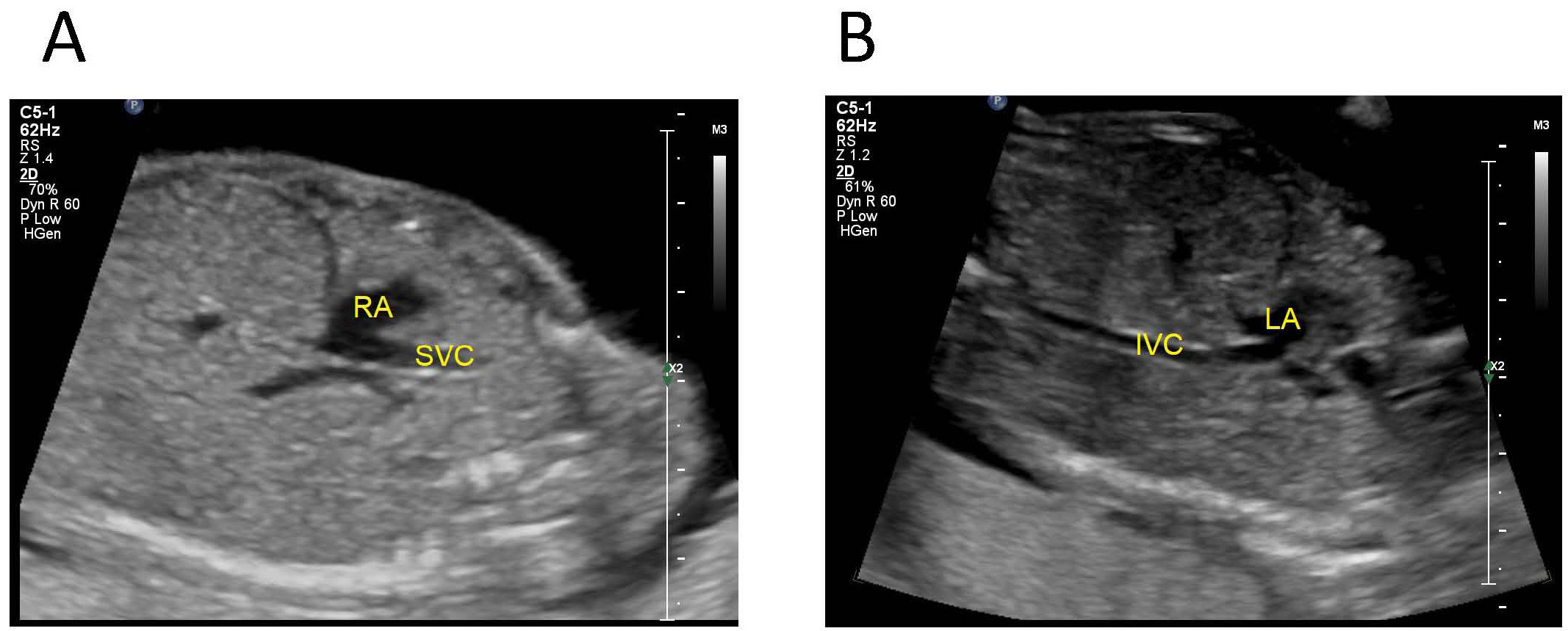

Fetus with abnormal connection of the IVC to the left atrium: the oblique coronal view of the fetal upper abdomen shows that the SVC drains into the right atrium and the IVC drains into the left atrium (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.Fetus with abnormal connection of the IVC to the left atrium. (A) tte oblique coronal view of the fetal upper abdomen shows that the SVC drains into the right atrium. (B) The IVC drains into the left atrium. IVC, inferior vena cava; SVC, superior vena cave; LA, left atrium; RA, right atrium.

Among the 180 fetuses, 33 cases had concomident intracardiac malformations (17 cases with interruption of the hepatic segment of the IVC, 6 cases with the interruption of the entire right IVC, 7 cases with left-sided IVC, 2 cases with double IVC, 1 case with abnormal connection of the IVC to the left atrium), There were 36 cases with concomident extracardiac malformations (21 cases with interruption of the hepatic segment of the IVC, 2 cases with the interruption of the entire right IVC, 9 cases with left-sided IVC and 4 cases with double IVC).

160 fetuses were liveborn, and their prenatal ultrasound diagnoses were confirmed by computed tomography (CT)/magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or surgery; the remaining 20 fetuses were terminated due to serious malformations (12 cases with interruption of the hepatic segment of the IVC, 2 cases with the interruption of the entire right IVC, 3 cases with left-sided IVC, 2 cases with double IVC, and 1 case with abnormal connection of the IVC to the left atrium), and their pathologic examination confirmed the prenatal ultrasound diagnoses. See Table 1.

| Type | Intracardiac malformations | Extracardiac malformations | Pregnancy outcomes |

| Interruption of the hepatic segment of the inferior vena cava (IVC) | |||

| 1 | Single atrium (SA), septal defect (VSD), hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) | Visceral inversion, left isomerism | Induction |

| 2 | Complete atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD), persistent left SVC | Visceral inversion, left isomerism | Induction |

| 3 | Dextroversion, SA, single ventricle (SV), outlet right ventricle (DORV) | Visceral inversion, left isomerism | Induction |

| 4 | Complete anomalous pulmonary venous connection (intracardiac) | None | Induction |

| 5 | SA and SV, persistent truncus arteriosus (PTA), complete anomalous pulmonary venous connection (supracardiac) | Visceral inversion | Induction |

| 6 | SA and SV, aortic atresia | Left isomerism | Induction |

| 7 | Fallot tetralogy | Duodenal atresia, visceral inversion, left isomerism | Induction |

| 8 | Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), VSD, right ventricular dilation into the left ventricle | Left isomerism | Induction |

| 9 | Pericardial effusion | Exomphalos (the content is liver), left isomerism | Induction |

| 10 | VSD, coarctation of the aorta | Left dacryocyst, left isomerism | Born |

| 11 | Dextrocardia | Left isomerism | Born |

| 12 | VSD | Left isomerism | Born |

| 13 | Partial anomalous pulmonary venous connection (intracardiac) | None | Born |

| 14–17 | Persistent left superior vena cava (PLSVC) | None | Born |

| 18–19 | None | Right Diaphragmatic hernia (the content is liver), left isomerism | Induction |

| 20–22 | None | visceral inversion, left isomerism | Born |

| 23 | None | Duodenal atresia, left isomerism | Induction |

| 24–27 | None | Visceral inversion | Born |

| 28–53 | None | None | Born |

| Interruption of the entire right IVC | |||

| 1 | PLSVC | Duodenal atresia, anal atresia | Induction |

| 2 | PLSVC, complete atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD), aortic atresia, complete anomalous pulmonary venous connection | Ascites, asplenia | Induction |

| 3–6 | PLSVC | None | Born |

| Stenosis of the hepatic segment of the right IVC | |||

| 1 none born | |||

| Left sided IVC | |||

| 1 | VSD, coarctation of the aorta | Agenesis of the corpus callosum (ACC), Bilateral choroid plexus cyst, hypertelorism, micrognathia, talipes of the left foot, bilateral syndactyly involving the forefinger and middle finger, cystic hygroma on the neck | Induction |

| 2 | PTA, pulmonary atresia, partial atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) | Bilateral absence of the radial bones, ulnar dysplasia, club hands | Induction |

| 3 | PTA, complete AVSD | Persistent right umbilical vein (PRUV) | Induction |

| 4 | PLSVC | None | Born |

| 5–6 | VSD | None | Born |

| 7 | VSD, PLSVC | Single umbilical artery (SUA) | Born |

| 8–9 | None | Bilateral nasal bone dysplasia | Born |

| 10 | None | Bilateral talipes | Born |

| 11 | None | Micrognathia, SUA | Born |

| 12 | None | Absence of the left kidney | born |

| 13–90 | None | None | born |

| Double IVC | |||

| 1 | None | Right ectopic kidney with polycystic development, hemivertebra | induction |

| 2 | PTA, levocardia | Visceral inversion | induction |

| 3 | Aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA) | None | born |

| ARSA | |||

| 4 | None | Horseshoe kidney | born |

| 5 | None | Left choroid plexus cyst | born |

| 6–29 | None | None | born |

| Abnormal connection of the IVC to the left atrium | |||

| 1 | DORV, complete AVSD, complete anomalous pulmonary venous connection | None | induction |

The development of the inferior vena cava is complex [4], consisting of the growth, regression and fusion of three pairs of embryonic veins, namely, the posterior cardinal, subcardinal and supracardinal and also being closely related to the vitelline vein. Between the 6th to 8th gestational week, the right branches of the above-mentioned veins, namely the right vitelline vein (the origin of the suprahepatic and retrohepatic IVC), the right subcardinal vein (the origin of the suprarenal IVC), the right supracardinal vein (the origin of the subrenal IVC) and the posterior cardinal vein (the origin of the main trunk of the IVC and the bilateral common iliac veins) will gradually anastomose. At the same time, their counterparts on the left would gradually degenerate and disappear, and that’s why the inferior vena cava is normally located on the right side. During this development, abnormalities concerning lumen degeneration or retention at different stages and areas, or abnormal development of other veins all have the possibility to cause malformations or aberrant connections of the IVC [5]. The failed connection between the right vitelline vein and the cardinal vein will result in the interruption of the IVC; the degeneration of the infrarenal segment of the right supracardinal vein with the retention of its left counterpart would result in a left-sided IVC; and the retention of both supracardinal veins will result in a double IVC. When IVC anomalies occur, the azygos and hemiazygos veins often become dilated. Normally, the azygos vein is located on the right side of the abdominal aorta, originating from the right ascending lumbar vein and rising to the T7~T8 level, receiving the transverse trunk of the accessory hemiazygos vein and the hemiazygos vein on the left. The hemiazygos vein is located on the left side of the abdominal aorta, originating from the left ascending lumbar vein, passing through the aortic hiatus and ascending in the left front of the spine, and eventually turning to the right at the level of T8 to drain into the azygos vein. The IVC starts from the level of L5, collects blood from both the left and right common iliac veins, ascends from the right side, then joins the hepatic veins below the diaphragm, and eventually drains into the right atrium [6].

The types of fetal IVC anomalies are complex and diverse. Liu et al. [7] reported a case with the interruption of the entire right IVC. In that case, the bilateral iliac veins and left renal veins drained into the hemiazygos vein, the right renal vein drained into the azygos vein, and the azygos vein crossed to the right of the abdominal aorta to join the azygos vein, which then joined the right SVC and finally returned to the right atrium. Pitt et al. [8] reported a case with the direct drainage of both the persistent left superior vena cava and inferior vena cava to the dilated coronary sinus. Vignesh et al. [9] reported a case with a double superior vena cava and double inferior vena cava. In that case, the right superior vena cava drained into the right atrium, the left superior vena cava drained into the left atrium, the right inferior vena cava drained into the right atrium, and the left inferior vena cava connected to the azygos vein and then drained into the left atrium. The above types did not appear in this study, but there was a special case of stenosis of the hepatic segment of the right IVC: the venous blood from the lower body had divided at the level of the renal hilum, with part of them draining to the stenotic hepatic IVC which drained into the right atrium, and the other part draining to the dilated azygos vein which joined the right superior vena cava and then back to the right atrium. This is an extremely rare type. Uzun et al. [10] reported that the decreased diameters of the fetal SVC and IVC may be related to fetal growth restriction. Therefore, when the azygos vein is found to be dilated, the hepatic IVC should be cautiously examined for evidence of interruption or stenosis. There was another special case of double IVC in this study: both the left and right IVC can be seen on both sides of the abdominal aorta below the level of the renal hilum in the fetal upper abdomen, and the left external iliac vein and the right common iliac vein draining into the right IVC, the left internal iliac vein draining directly into the left IVC and crossing the front of the abdominal aorta at the level of the renal hilum to drain posteriorly into the right IVC. In this study, there was another extremely rare case in which the IVC was abnormally connected to the left atrium and the SVC connected into the right atrium. This type was first reported by Gardner and Cole in 1955 [11] and the earliest surgical repair was accomplished by Nasseri et al. [12] in 1964. The suspected etiology might be the fusion of the residual right atrial valve from incomplete degeneration in the embryonic period with the second interatrial septum, resulting in dislocation of the IVC entrance to the left atrium. In addition to the interrupted IVC, the SVC can also have complex and various abnormal connections. Zhang et al. [13] reported that in a case of bilateral interruption of the IVC resulting in superior vena cava syndrome, the blood in the upper body returned to the right atrium through the superficial veins in the chest and upper abdomen, great saphenous vein, common femoral vein, and inferior vena cava. As for the ductus venosus in this study, one case of interrupted IVC (the hepatic segment) was complicated with the ductus venosus connecting to the left hepatic vein and then draining to the right atrium. In the other 58 cases of interrupted IVC and 1 case with the IVC connecting to the left atrium, all had the ductus venosus directly entering the right atrium. For cases of left-sided IVC, double IVC and stenosis of hepatic segment of IVC, the ductus venosus connected to the IVC normally and then drained into the right atrium.

Interruption of the IVC may exist alone and also may be combined with other intra- or extracardiac malformations, particularly with left isomerism [14]. Characteristic malformations associated with left-sided IVC and double IVC have not been reported in the literature. Left isomerism, also known as polysplenic syndrome, is characterized by bilateral organs sharing the same morphology of the organs on the left side. For instance, both the left and right auricles share the morphological structure of the left auricle, both lungs are bilobed, there are duplicated spleens, and either situs solitus, situs inversus or situs ambiguous may exist. Some cases are complicated by heart block and the normally right-sided organs may be interrupted or hypoplastic. Right isomerism syndrome, also known as asplenia syndrome, is characterized by similar morphology of the both auricles and both atria, a trilobed structure of both lungs, a vague position of gastric bubble, a centripetal liver, asplenia, and absence or hypoplasia of the normally left sided organs. Both left isomerism syndrome and right isomerism syndrome belong to heterotaxy syndrome. In our study, there was 1 case of interrupted IVC combined with asplenia. However, the current literature and our sample data cannot explain the correlation between interrupted IVC and right isomerism syndrome, and further research is needed. In this study, the most common intracardiac malformations were atrial and ventricular septal defects, followed by anomalous pulmonary venous connection (supracardiac or intracardiac), single atrium, single ventricle, and conotruncal anomalies (persistent truncus arteriosus, double outlet right ventricle and tetralogy of Fallot). The most common extracardiac malformations included situs inversus and left isomerism, followed by duodenal atresia and right diaphragmatic hernia, indicating that the interrupted IVC is often co-existing with situs inversus and left isomerism. In this study, stenosis of the hepatic segment of the right IVC was not complicated by intra- or extracardiac malformations. As for the left-sided IVC, there were 7 cases combined with intracardiac malformations (mainly VSD) and another 9 cases with extracardiac malformations. Among the cases of double IVC, 2 cases were combined with intracardiac malformations and 4 with extracardiac malformations. There was only 1 case of abnormal connection of the IVC to the left atrium, which was combined with double outlet of the right ventricle, complete atrioventricular septal defect, complete anomalous pulmonary venous connection, and without any extracardiac malformations. Common clinical manifestations for this type include shortness of breath after exertion, cyanosis and clubbed fingers, low blood oxygen saturation, and hyperhemoglobinaemia. Some patients may be asymptomatic, and their clinical manifestations are similar to Budd-Chiari syndrome or hepatopulmonary syndrome [15, 16]. There were no cases that had hydrops fetalis in our study. A larger population for better observation of more potential associated abnormalities is needed for further study. Therefore, when signs of fetal IVC anomalies are found on prenatal ultrasound, careful scanning should be performed for evidence of any intra- or extracardiac malformations [17, 18].

Abnormal IVC is an incidental finding if isolated. We suggest that it is necessary to include more informative examinations such as the chromosomal tests whether the IVC abnormality is isolated or not. The pregnancy outcomes of inferior vena cava anomalies mainly depend on the severity of the combined malformations. IVC anomalies alone does not effect obvious hemodynamic changes or symptoms, therefore it generally does not require surgical treatment and usually has a good prognosis. However, attention is still required to have a clear picture in order to preclude severe bleeding as more chest and abdominal surgeries involve the IVC [19]. In this study, 160 fetuses were born and followed up to 1 year after birth. No obvious abnormalities were found in any of them. The literature reported a patient with interrupted IVC and dilation of the hemiazygos vein, combined with left isomerism and complete atrioventricular block, which was an important factor in the patient’s death [20]. It has been reported [21, 22] that patients with IVC anomalies are more likely to have venous insufficiency and deep vein thrombosis. The reasons may be related to poor perfusion during the fetal period, maternal diabetes, genetics or other factors [23]. In addition to deep vein thrombosis, complications that occur in patients with interrupted IVC include pulmonary thromboembolism [24], and pelvic congestion syndrome [25], which may be related to genitourinary and cardiac defects [26]. Thrombus may also form in the IVC during the fetal period [27]. Therefore, stenosis of the hepatic IVC during the fetal period should be closely followed up and observed. The cases with left-sided IVC or double IVC generally have no special clinical manifestations. When the crossing segment experiences increased compression, the left renal vein is often involved, resulting in an increase in left renal venous pressure, an increased risk of hematuria and testicular spermatic vein varicose in the male patient. Some patients may develop nutcracker syndrome [28]. The prognosis for abnormal connection of the IVC to the left atrium is poor, and early prenatal diagnosis is of great significance in guiding clinical treatment. The international scientific societies (Medicina Fetal Barcelona) guide-lines for the advanced fetal echocardiography include additional views using Doppler in demonstration of a systemic venous return to the right atrium and the presence of the ductus venosus, Medicina Fetal Barcelona (BCN) assessing presence of the inferior vena cava (IVC) as an essential component of fetal echocardiography, indicating fetal inferior vena cava abnormality might cause poor fetal outcomes [29].

A total of 6 cases in this study underwent chromosome tests, and among them, 1 case was confirmed with trisomy 21, while the other 5 cases being negative. The case with trisomy 21 is the case with abnormal connection of the IVC to the left atrium. However, as the case had other serious malformations including double outlet of the right ventricle, complete atrioventricular septal defect and complete anomalous pulmonary venous connection, the correlation between the chromosomal finding and abnormal connection of the IVC to the left atrium remains vague and needs further study. Typical signs of atrial isomerism are difficult to display during the fetal period due to the limitations of the imaging technique and can be easily missed. Therefore, a careful and dynamic examination across multiple views during the ultrasound examination is necessary. As the sample size of cases with special conditions in this study is relatively small, data from more regions needs to be collected for further research and analysis.

In conclusion, prenatal ultrasound can clearly demonstrate the image characteristics of fetal IVC anomalies and the associated intra- or extracardiac malformations. A cautious prenatal ultrasound should be performed for any signs of the anomalies and the associated malformations. Close follow-up and observation are recommended for IVC anomalies without other co-existing malformations.

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. The data of this study are available upon request.

HYY conceived the study. HYY and YK processed the images, drafted and revised the manuscript. CGZ and YK analyzed the data and interpreted the data. HYY and LHH proposed the idea, and designed the work. LHH supervised the total study, and revised the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Sichuan Provincial Maternity and Child Health Care hospital (approval no. HUSLL 20211216-132). Written informed consent was obtained from participants prior to the study.

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.