1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, West China Second Hospital, Sichuan University, 610041 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

2 Key Laboratory of Birth Defects and Related Diseases of Women and Children, Ministry of Education, Sichuan University, 610041 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

3 Department of Nursing, Neonatology, West China Second Hospital, Sichuan University, 610041 Chengdu, Sichuan, China

Abstract

Background: Studies on the effect of intracytoplasmic injection of hyaluronan-bound spermatozoa (HA-ICSI) on infertility are insufficient, and its use in treating patients remains controversial. Therefore, we aimed to determine the effectiveness of HA-ICSI in couples with infertility. Methods: A systematic literature review and meta-analysis were conducted to explore the effect of HA-ICSI on couples with infertility. All studies were examined using relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (95% CI). Results: A total of 1174 publications were retrieved, of which 16 (10 randomized controlled trials (RCTs), five cohort trials, and one publication, including an RCT and a cohort trial) were considered eligible for inclusion. Meta-analysis of the cohort studies indicated a significant advantage for HA-ICSI in terms of live birth rate (LBR), clinical pregnancy rate (CPR), biochemical pregnancy rate (BPR), implantation rate (IR), fertilization rate (FR), and good-quality embryo rate. No difference in spontaneous abortion rate (SAR) or cleavage rate between the HA-ICSI and conventional intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) groups was observed. Based on the pooled results of all available studies and RCTs, SAR was significantly reduced in the HA-ICSI group than in the conventional ICSI group. The benefits of CPR, IR, and FR were recognized in the pooled results of all available studies; however, RCT analysis did not demonstrate these benefits. Conclusions: The cohort studies indicated a significant advantage of HA-ICSI in terms of LBR, CPR, BPR, IR, FR, and good-quality embryo rates. In RCTs, HA-ICSI significantly reduced the SAR compared to conventional ICSI. Further RCTs with larger sample sizes are required to confirm the beneficial effects of HA-ICSI.

Keywords

- hyaluronan

- intracytoplasmic sperm injection

- sperm election

- meta-analysis

Intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) improves fertilization rate (FR) in couples with male factor infertility. ICSI is a significant achievement in assisted reproductive technology (ART) and has become probably the most important therapy for male infertility in recent years. Globally, ICSI use is increasing, mainly because of increased ICSI use in cycles carried out for non-male factors, such as frozen oocytes, in vitro maturation of human immature oocytes, preimplantation genetic testing, and infertility with previous fertilization failure. ICSI use has been observed in 70–80% of fresh cycles, with increasing applications encountered [1]. ICSI is considered the most “revolutionary” in vitro insemination technique since an embryologist artificially selects a single spermatozoon for injection, which can fertilize an oocyte notwithstanding its morphology or motility. Additionally, some natural fertilization processes, such as sperm-cumulus interaction, sperm-zone penetration, and acrosome reaction, are circumvented in the ICSI process [2]. During conventional ICSI, sperm are selected based on motility and morphology, which may not reflect sperm quality. Theoretically, the prominent use of ICSI may increase the possibility of injecting spermatozoa that are defective in centrosome integrity, genetic constitution, phospholipase C zeta content, or DNA methylation [3, 4, 5]. Embryo quality is influenced by the quality of gametes, oocytes, and spermatozoa. Natural barriers to fertilization are circumvented in ICSI; therefore, embryo quality is affected. Therefore, ICSI treatments may be optimized by selecting the ideal spermatozoa before injection. However, the shapes of individual spermatozoa do not indicate chromatin integrity and chromosomal aberrations. Visual shape assessment, which selects the best-looking sperm during ICSI, is unreliable and may result in abnormal chromosomes in subsequent developmental stages [6, 7]. Concerns regarding the potential adverse effects of ICSI on subsequent fertilization, embryo development, and offspring health owing to deviations from natural selection exist. Therefore, a practical test for selecting healthy sperm for ICSI is required.

Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) is used in conventional ICSI to reduce sperm velocity and facilitate the smooth injection of oocytes. However, PVP causes submicroscopic changes in sperm structure and damages sperm membrane integrity and sperm nucleus [8, 9]. Moreover, human oocytes are unable to degrade PVP, subsequently affecting pregnancy rates [10, 11, 12].

Recently, several sperm-selection techniques have been developed. These techniques are categorized into methods based on sperm density, morphology, motility, membrane integrity, surface charge, and nuclear integrity. However, these techniques have not demonstrated enhanced clinical outcomes that would support routine clinical application despite their ability to improve sample quality.

Hyaluronan (hyaluronic acid, HA) is a linear anionic polysaccharide containing

N-acetyl-D-glucosamine and D-glucuronic acid bound with

Theoretically, the selection of HA-bound sperm for ICSI facilitates

fertilization and produces high-quality embryos, leading to better clinical

outcomes. Studies on intracytoplasmic injection of hyaluronan-bound spermatozoa

(HA-ICSI) are insufficient, and the application of HA-ICSI to treat infertility

remains controversial, although it has been used for over a decade. HA-ICSI

includes HA-coated dishes (PICSI dishes) and HA-containing media

(SpermSlow

This systematic review and meta-analysis was previously registered with PROSPERO (CRD42024540998) and followed PRISMA guidelines. A comprehensive PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane search was performed to identify studies aimed at comparing the clinical outcomes of HA-ICSI with those of conventional ICSI in couples with infertility. The search was restricted to papers fully published in English on 13 October, 2023, using the following keywords: (“sperm” or “spermatozoa” or “spermatozoon” or “IVF” or “in vitro fertilization” or “ICSI” or “intracytoplasmic sperm injection”) and (“hyaluronic acid” or “hyaluronan”). Our study’s title and abstract were used to screen all items retrieved from the primary search. Irrelevant items were removed, and the articles of potential interest were further investigated for citations that met the inclusion criteria. We also manually reviewed the bibliographies of original and reviewed articles.

All studies investigating the effect of HA-ICSI met the following inclusion criteria: (1) randomized controlled trials (RCTs) or cohort trials, (2) had outcomes, such as live birth rate (LBR), clinical pregnancy rate (CPR), spontaneous abortion rate (SAR), biochemical pregnancy rate (BPR), implantation rate (IR), fertilization rate (FR), cleavage rate, and good-quality embryo rate, and (3) published in English.

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (1) no original data for retrieval, (2) duplicate publications, (3) no full texts, and (4) review articles, case reports, or comments from editors. Two authors independently identified relevant studies, and any discrepancies were discussed.

Two authors independently extracted data from each included article. The extracted data included the first author’s name, year of publication, country, study design and period, HA-binding methods, control group, number of cycles or patients in the HA and control groups, and inclusion and exclusion criteria. Disagreements between the two authors were resolved through discussion. A third reviewer’s input was required for unresolved disagreements.

The Cochrane Collaboration tool was used to evaluate the methods of random

allocation, the presence and quality of allocation concealment and blinding, and

the existence of incomplete outcome data and selective outcome reporting for all

included RCTs [25]. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale (NOS) was used to evaluate the

quality of individual cohort studies. The NOS uses a star system with a maximum

of nine stars to assess a study in three domains: selection of study groups,

comparability of groups, and ascertainment of interest outcome. We determined

studies that received a score of nine stars to be of a low risk of bias. Studies

scoring seven or eight stars were of a moderate risk of bias, and those scoring

The effect of HA-ICSI was examined using relative risk (RR) with 95% confidence

intervals (95% CI). The Q (significance level of p

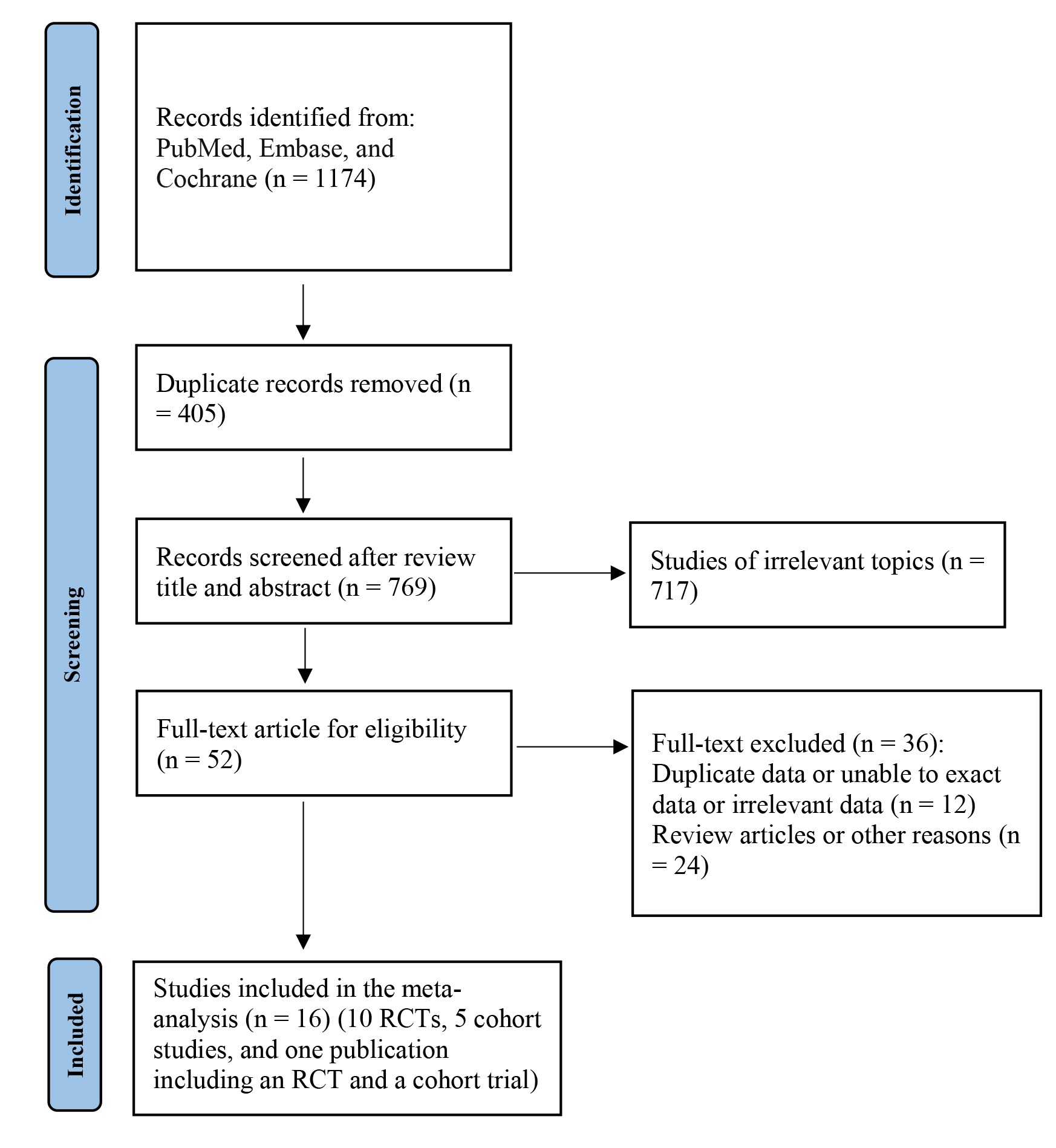

A total of 1174 results were obtained from the PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases and other sources. A total of 1122 articles were excluded after reading the titles and abstracts. Two authors read the full texts of the 52 articles, and 16 articles were finally analyzed (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Flowchart of the selection of studies for inclusion in this meta-analysis. RCTs, randomized controlled trials.

A total of 16 publications (10 RCTs, five cohort studies, and one publication, including an RCT and a cohort trial) met the inclusion criteria and were analyzed in our study [19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35]. Table 1 (Ref. [19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35]) summarizes the characteristics of the included studies.

| Author, Year of publication | Country | Study design/period | Hyaluronic acid binding methods | Control group | Number of cycles/patients in HA-ICSI group | Number of cycles/patients in control group | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

| Scaruffi P, et al. 2022 [19] | Italy | Cohort/not mentioned | Sperm Slow | Polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP)-ICSI | 104 cycles | 101 cycles | In 2010–2020, patients had a failed ICSI cycle which had a low fertilization rate and poor embryo quality. Only fresh oocytes and ejaculated sperm. | Egg or sperm donors. |

| Novoselsky Persky M, et al. 2021 [20] | Israel | RCT/January 2017 to April 2020 | PICSI | PVP-ICSI | 45 cycles | 45 cycles | Patients had a failed cycle with poor fertilization, poor embryo quality, repeated implantation failure, or repeated pregnancy loss. | Cycles in which only a single method was used. |

| Rezaei M, et al. 2021 [21] | Iran | Cohort/August 2016 to Jun 2020 | PICSI | PVP-ICSI | 16 cycles | 18 cycles | Sperm count |

Patients with normozoospermia, seminal infection, asthenozoospermia, testicular sperm, systemic diseases or a history of cryptorchidism. |

| Kim SJ, et al. 2020 [22] | Korea | Cohort/From January 2016 to December 2018 | Sperm Slow | Standard ICSI | 77 patients | 75 patients | Sperm morphology with |

Not mentioned. |

| Liu Y, et al. 2019 [26] | Australia | RCT/between July 2014 and March 2015 | Sperm Slow | PVP-ICSI | 21 cycles | 21 cycles | Patients allowed to use of the Embryoscope |

Motile sperm count |

| Miller D, et al. 2019 [23] | UK | RCT/from February 1, 2014 to August 31, 2016 | PICSI | Standard ICSI | 1381 patients | 1371 patients | Women were 18–43 years old; women’s BMI was 19–35 kg/m |

Donor or frozen gametes or undergoing split IVF–ICSI. Men had a vasovasostomy or were treated for cancer in the 24 months before recruitment. |

| Erberelli RF, et al. 2017 [27] | Brazil | Cohort/July 2013 to July 2014 | PICSI | PVP-ICSI | 19 cycles | 37 cycles | Moderate to severe male factor. | Percutaneous epididymal sperm aspiration (PESA), testicular sperm aspiration (TESA) or micro TESA. |

| Troya J and Zorrilla I 2015 [24] | Peru | RCT/From January 2013 to July 2014 | Sperm Slow | PVP-ICSI | 47 patients | 55 patients | Infertile patients having normal sperm concentration in according to WHO 2010 criterion. | Endometriosis. |

| Majumdar G and Majumdar A 2013 [28] | India | RCT/January to November 2012 | PICSI | PVP-ICSI | 71 patients | 80 patients | Unexplained infertile patients with normal semen parameters in according to WHO 2010 criterion for first cycle. | Age |

| Worrilow KC, et al. 2013 [29] | USA | RCT/2-year period | PICSI | standard ICSI | 237 patients | 245 patients | Patients received ICSI treatment. | Patients using testicular sperm, donor or cryopreserved gametes; patients receiving preimplantation genetic diagnosis, sperm sorting, or a partial ICSI. Women was |

| Choe SA, et al. 2012 [30] | Korea | RCT/between July and December 2011 | Sperm Slow | PVP-ICSI | 18 patients | 112 patients | Women were 30–42 years old; serum FSH level on menstrual day 3 |

Women were |

| Parmegiani L, et al. 2010 [31] | Italy | Cohort/January 2005 to January 2009 | Sperm Slow | PVP-ICSI | 293 patients | 86 patients | Women were |

Not mentioned. |

| Parmegiani L, et al. 2010 [32] | Italy | RCT/March 2004 to December 2005 | Sperm Slow | PVP-ICSI | 125 cycles | 107 cycles | Ejaculate motile sperm count |

Not mentioned. |

| Van Den Bergh MJ, et al. 2009 [33] | Switzerland | RCT, cohort/not mentioned | Sperm Slow | RCT: HA unbound sperm; Cohort: PVP-ICSI | RCT: 44 patients; Cohort: not mentioned | 44 patients Not mentioned | Woman was |

Patients with frozen–thawed ejaculated sperm, fresh or frozen–thawed epidydymal, or testicular sperm; non-progressive spermatozoa. |

| Ciray HN, et al. 2008 [34] | Turkey | RCT/March 2007 | PICSI | HA unbound sperm | 10 cycles | 10 cycles | First cycle with |

Not mentioned. |

| Balaban B, et al. 2003 [35] | Sweden | RCT/not mentioned | Sperm Catch |

PVP-ICSI | 48 patients | 44 patients | Patients with male factor infertility. | Not mentioned. |

HA-ICSI, hyaluronan-bound spermatozoa; ICSI, intracytoplasmic sperm injection; RCT, randomized controlled trials; PICSI, HA-coated; BMI, body mass index; FSH, follicle-stimulating hormone; AMH, anti-mullerian hormone; IVF, in vitro fertilization; WHO, World Health Organization.

A total of 4, 2, 5, and 10 RCTs were at low risk for random sequence generation and allocation concealment, blinding of outcome assessment, outcome completion, and outcome selective reporting, respectively. None of the trials had a low risk of blinding the participants or other biases. Table 2 (Ref. [20, 23, 24, 26, 28, 29, 30, 32, 33, 34, 35]) presents the details of the risk of bias assessment. Furthermore, of the six cohort trials, four studies had a moderate risk of bias, and two had a high risk of bias (Table 3, Ref. [19, 21, 22, 27, 31, 33]).

| References | Random sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants | Blinding of outcome assessment | Outcome complete | Outcome selective reporting | Other bias |

| Novoselsky Persky M, et al. 2021 [20] | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | High risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Liu Y, et al. 2019 [26] | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | High risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Miller D, et al. 2019 [23] | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Troya J and Zorrilla I 2015 [24] | Unclear | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | High risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Majumdar G and Majumdar A 2013 [28] | Low risk | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | High risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Worrilow KC, et al. 2013 [29] | Low risk | Low risk | High risk | Unclear | High risk | High risk | High risk |

| Choe SA, et al. 2012 [30] | Low risk | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Parmegiani L, et al. 2010 [32] | Unclear | Low risk | High risk | Unclear | High risk | Low risk | High risk |

| Van Den Bergh MJ, et al. 2009 [33] | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Ciray HN, et al. 2008 [34] | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Balaban B, et al. 2003 [35] | Unclear | Unclear | High risk | Unclear | Low risk | Low risk | Unclear |

| Study | Selection | Comparability | Outcome | Summary score |

| Scaruffi P, et al. 2022 [19] | ✩✩✩ | ✩ | ✩✩✩ | 7 |

| Rezaei M, et al. 2021 [21] | ✩✩✩ | / | ✩✩✩ | 6 |

| Kim SJ, et al. 2020 [22] | ✩✩✩ | ✩ | ✩✩✩ | 7 |

| Erberelli RF, et al. 2017 [27] | ✩✩✩ | ✩ | ✩✩✩ | 7 |

| Parmegiani L, et al. 2010 [31] | ✩✩✩ | ✩✩ | ✩✩✩ | 8 |

| Van Den Bergh MJ, et al. 2009 [33] | ✩✩✩ | / | ✩✩✩ | 6 |

A star system with a maximum of nine stars was used to assess a study in three domains.

We evaluated the LBR between the HA-ICSI and conventional ICSI groups in six

studies (five RCTs and one cohort study). The statistical analysis performed

using the random effects model revealed no significant difference in the LBR

between the two groups (RR = 1.25, 95% CI: 0.94–1.65); however, a high

heterogeneity was observed (I

A total of eight RCTs and four cohort studies reported the CPR between the

HA-ICSI and conventional ICSI groups. The pooled results suggested that CPR was

significantly higher in the HA-ICSI group than in the conventional ICSI group (RR

= 1.21, 95% CI: 1.01–1.43), with a high heterogeneity observed

(I

A total of six RCTs and three cohort studies that provided SAR data were

included in our meta-analysis. A significantly lower SAR was observed in the

HA-ICSI group than in the conventional ICSI group (RR = 0.65, 95% CI:

0.50–0.84), with no heterogeneity observed (I

We compared the BPR between the HA-ICSI and conventional ICSI groups in seven

studies (five RCTs and two cohort studies). The meta-analysis revealed no

significant difference between the two groups (RR = 1.16, 95% CI: 0.93–1.46);

however, a moderate heterogeneity was observed (I

Pooled results from three RCTs and two cohort studies indicated a significantly

higher IR in the HA-ICSI group than in the conventional ICSI group (RR = 1.43,

95% CI: 1.01–2.04), with high heterogeneity observed (I

| No. of studies | RR (95% CI) | Test of heterogeneity | |||

| p value | I | ||||

| Live birth rate | |||||

| all | 6 | 1.25 (0.94, 1.65) | 0.080 | 49.3 | |

| RCT | 5 | 1.09 (0.98, 1.21) | 0.950 | 0.0 | |

| cohort study | 1 | 3.20 (1.59, 6.42) | - | - | |

| Clinical pregnancy rate | |||||

| all | 12 | 1.21 (1.01, 1.43) | 0.010 | 53.5 | |

| RCT | 8 | 1.00 (0.92, 1.09) | 0.890 | 0.0 | |

| cohort study | 4 | 1.86 (1.40, 2.48) | 0.470 | 0.0 | |

| Spontaneous abortion rate | |||||

| all | 9 | 0.65 (0.50, 0.84) | 0.820 | 0.0 | |

| RCT | 6 | 0.63 (0.48, 0.85) | 0.950 | 0.0 | |

| cohort study | 3 | 0.72 (0.39, 1.36) | 0.200 | 38.7 | |

| Biochemical pregnancy rate | |||||

| all | 7 | 1.16 (0.93, 1.46) | 0.070 | 48.8 | |

| RCT | 5 | 1.00 (0.92, 1.10) | 0.750 | 0.0 | |

| cohort study | 2 | 1.94 (1.30, 2.91) | 0.380 | 0.0 | |

| Implantation rate | |||||

| all | 5 | 1.43 (1.01, 2.04) | 0.020 | 64.6 | |

| RCT | 3 | 1.11 (0.86, 1.45) | 0.730 | 0.0 | |

| cohort study | 2 | 2.03 (1.45, 2.83) | 0.110 | 61.7 | |

| Fertilization rate | |||||

| all | 11 | 1.05 (1.00, 1.09) | 0.001 | 65.8 | |

| RCT | 7 | 1.02 (0.97, 1.07) | 0.090 | 45.0 | |

| cohort study | 4 | 1.10 (1.06, 1.14) | 0.100 | 51.8 | |

| Cleavage rate | |||||

| all | 6 | 0.97 (0.94, 0.99) | 0.002 | 74.3 | |

| RCT | 3 | 0.98 (0.94, 1.03) | 0.060 | 64.2 | |

| cohort study | 3 | 0.96 (0.92, 1.01) | 0.010 | 78.5 | |

| Good-quality embryo rate | |||||

| all | 7 | 1.19 (0.97, 1.46) | 83.8 | ||

| RCT | 5 | 1.04 (0.90, 1.21) | 0.080 | 51.9 | |

| cohort study | 2 | 1.56 (1.36, 1.79) | 0.930 | 0.0 | |

RR, relative risk; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

A total of seven RCTs and four cohort studies provided FR data and were included

in the meta-analysis. The overall results showed a significantly higher FR in the

HA-ICSI group than in the conventional ICSI group (RR = 1.05, 95% CI:

1.003–1.09), with high heterogeneity observed (I

We evaluated the cleavage rate between the HA-ICSI and conventional ICSI groups

in six studies (three RCTs and three cohort studies). The meta-analysis revealed

a significantly lower cleavage rate in the HA-ICSI group than in the traditional

ICSI group (RR = 0.97, 95% CI: 0.94–0.999), with high heterogeneity observed

(I

We evaluated the good-quality embryo rate between the HA-ICSI and conventional

ICSI groups in seven studies (five RCTs and two cohort studies). No significant

difference between the two groups was observed (RR = 1.19, 95% CI: 0.97–1.46),

with high heterogeneity observed (I

In our meta-analysis, evidence of a publication bias was observed. Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s linear regression for CPR yielded p values of 0.19 and 0.04, respectively. In addition, for studies examining FR, Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s linear regression yielded p values of 0.88 and 0.57, respectively.

Our meta-analysis included RCTs and cohort studies. We identified whether HA-ICSI was beneficial for patients compared to conventional ICSI in terms of LBR, CPR, SAR, BPR, IR, FR, cleavage rate, and good-quality embryo rate. We screened 16 publications (10 RCTs, five cohort studies, and one publication, including an RCT and a cohort trial). Our meta-analysis of the cohort studies indicated a significant advantage for HA-ICSI in terms of LBR, CPR, BPR, IR, FR, and good-quality embryo rate, and no differences in SAR and cleavage rate between the HA-ICSI and control groups. Compared with that in the conventional ICSI group, the SAR in the HA-ICSI group significantly decreased in a meta-analysis of all available studies and RCTs. Similar to the RCT results, a meta-analysis of all studies revealed no difference between the HA-ICSI and control groups in terms of LBR, BPR, and good-quality embryo rates. The advantages of CPR, IR, and FR have been recognized in a meta-analysis of all available studies. However, a meta-analysis of RCTs did not demonstrate these advantages. HA-ICSI significantly decreased the cleavage rate in the meta-analysis of all available studies; however, for RCTs, no difference in the cleavage rate between the HA-ICSI and conventional ICSI groups was observed.

Our conclusions differ from those of the previous studies. Based on data from four RCTs, Lepine S, et al. [36] discovered that HA-ICSI reduced miscarriage but did not improve LBR or CPR. When our meta-analysis was limited to data sets from RCTs, we obtained similar results. RCTs have superior study designs owing to their internal validity; however, they may lack external validity [37, 38, 39]. Therefore, it is necessary to include cohort studies. Beck-Fruchter R, et al. [40] reviewed six RCTs and two cohort studies. It was concluded that using the HA-ICSI technique yielded no improvement in fertilization and pregnancy rates. A meta-analysis of all available studies showed an improvement in embryo quality and IR, and a meta-analysis of RCTs only revealed an improvement in embryo quality. We conducted a meta-analysis of all cohort studies and recent RCTs, resulting in an extensive dataset for analysis and different results. Our meta-analysis and systematic review, including RCTs and cohort studies, are the most comprehensive analyses of the effects of HA binding on sperm selection in ICSI. In contrast to previous reviews, we thoroughly searched for relevant articles and updated some recent studies.

I

For the cohort studies, none of the outcomes varied significantly with the removal of any study, demonstrating that the results were not highly influenced by any study, suggesting the stability and reliability of the findings. For RCTs, all outcomes, except the SAR, did not vary with the removal of any study, demonstrating that the meta-analysis was thorough and that none of the studies greatly influenced the results. However, in our meta-analysis, the SAR outcome in RCTs was unreliable. Six RCTs reported SARs, excluding the study conducted by Miller D, et al. [23], which led to a different result of no significant difference in the SAR between the two groups, similar to the pooled results of cohort studies. Therefore, we suggest that the pooled SAR result in RCTs was greatly influenced by the study by Miller D, et al. [23], in which 2772 couples undergoing ICSI were randomly assigned to receive either HA-ICSI or conventional ICSI, and a lower miscarriage rate in HA-ICSI was observed. Additionally, the results of most of the included studies were not significant.

Our study had several limitations. First, the significant problem was that the

results showed a high degree of statistical heterogeneity in some analyses. We

conducted a subgroup analysis and discovered that the design and methodological

differences between the RCTs and cohort studies may have contributed to the high

heterogeneity observed. However, we were unable to eliminate the effects of other

factors, such as the etiology of infertility, ovarian stimulation protocols, and

exclusion criteria, which were not available for subgroup analysis owing to

insufficient data. Moreover, the use of Embryoscope

Notwithstanding these limitations, our analysis included recently published articles, which provided greater detail on ICSI outcomes and focused on subgroup analysis according to the included study designs, leading to an increased significance of our meta-analysis. Additionally, most of the meta-analyzed studies demonstrated improved clinical outcomes with HA-ICSI. No study reported that HA-ICSI adversely affected ICSI outcomes. If a comprehensive multicenter prospective randomized study confirms the positive effects of HA-ICSI, HA-ICSI is a potential first-line infertility treatment for ‘physiological’ sperm selection before ICSI because of its ability to reduce genetic complications and its non-toxic state.

In summary, the cohort studies indicated a statistically significant advantage of HA-ICSI in terms of LBR, CPR, BPR, IR, FR, and good-quality embryo rate. All included studies and RCTs revealed that HA-ICSI significantly decreased SAR compared to conventional ICSI. The advantages of CPR, IR, cleavage rate, and FR have been recognized in a meta-analysis of all available studies. However, a meta-analysis of RCTs did not demonstrate these advantages. HA-ICSI did not have detrimental effects on ICSI outcome parameters. Extensive multicenter prospective randomized studies are required to confirm the beneficial effects of HA-ICSI. Additionally, HA-ICSI should be considered for physiological sperm selection before ICSI.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this article. Further enquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

WF designed and performed the study, collected and analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. WG collected and analyzed the data, reviewed and edited the manuscript. QC collected and analyzed the data and reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Not applicable.

Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at https://doi.org/10.31083/j.ceog5106147.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.