1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Faculty of Medicine, Mutah University, 61710 Al-Karak, Jordan

2 Department of Anatomy, Histology and Embryology, Faculty of Medicine, Mutah University, 61710 Al-Karak, Jordan

3 Department of Anatomy and Embryology, Faculty of Medicine, Zagazig University, 44519 Zagazig, Egypt

4 Department of Community Medicine and Public Health, Faculty of Medicine, Mutah University, 61710 Al-Karak, Jordan

5 High Institute of Public Health, Alexandria University, 21526 Alexandria, Egypt

6 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Mutah University, 61710 Al-Karak, Jordan

7 Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Faculty of Medicine, Minia University, 61519 El-Minia, Egypt

Abstract

Background: Fetal exposure to maternal smoking has been

implicated as a contributing factor to birth complications and subsequent

developmental impairments in children. The aim of the present study was to

investigate the association between maternal smoking and pregnancy outcomes in a

sample of women giving birth at hospitals in southern Jordan.

Methods: This observational study extracted data from the

medical records of enrolled pregnant women, including demographic information,

vital signs, and newborn measurements. Specific data included birth type

(miscarriage or no miscarriage), birthweight, head circumference, Apgar score,

and labor (term or pre-term). A two-tailed p-value of

Keywords

- birth

- head circumference

- miscarriage

- preterm

- smoking

Smoking during pregnancy has adverse health consequences for the mother and baby [1]. It is associated with various complications including premature rupture of membranes, placenta previa, pre-term labor, spontaneous miscarriage, intrauterine growth retardation, fetal birth restriction, low birthweight and size, sudden infant death syndrome, as well as neurodevelopment disorders, cognitive disabilities, and long-term cancer risks in infants [2, 3, 4, 5, 6]. Smoking can also lead to small head circumference, low Apgar score, stillbirths, and neonatal deaths. Moreover, smoking can increase the rate of cesarean births and the rates of morbidity and mortality in newborn infants [7]. To reduce these risks, it is vital to minimize smoking by the mother throughout pregnancy and after birth. Several studies have reported differences in neonatal birthweight between mothers who are cigarette smokers and those who are non-smokers [8, 9, 10].

Passive, or involuntary smoking may be of particular importance in Jordan due to the high prevalence of passive smokers among women. Little is known about the dangerous effects on birth outcomes of smoking and even passive smoking throughout pregnancy [11]. A self-report questionnaire study on exposure to second-hand smoke found that despite being aware of the importance of indoor environments on respiratory symptoms, family members in a significant proportion of households (71%) still smoked indoors [12].

The prevalence of tobacco smoking among pregnant women during pregnancy is estimated to be 9%, 12%, 16% and 7% in Germany, the UK, France, and the USA, respectively [13]. It is difficult to accurately estimate the incidence of smoking by women during pregnancy, especially in socially disadvantaged areas. This is due to the social and medical pressures faced by pregnant women who smoke [14]. In Jordan, the prevalence of smoking among women was reported to be 10.9%, with the highest incidence found in wealthier (15.5%) and less educated (17.2%) groups. Furthermore, urban areas had a higher incidence of female smokers (11.8%), and the highest prevalence was observed in 40–49 years old women (15.1%) [15, 16].

The mechanisms underlying the harmful effects of smoking during pregnancy are not fully understood, but are likely to involve the nocive effects of nicotine and carbon monoxide. These reduce uteroplacental circulation, fetal tissue oxygenation and maternal weight gain, as well as having undesirable consequences for the fetus. In addition, the 4000 potentially toxic substances found in cigarettes may harm the health of the mother and baby. The effect of nicotine on brain development may also lead to behavioral problems in children [9].

The aim of the present study was to investigate the association between maternal smoking and pregnancy outcomes in a sample of women giving birth at hospitals in southern Jordan. We also examined associations between smoking and prematurity, Apgar score, birthweight, and head circumference.

This study was conducted from January to June 2022 at two major hospitals in Southern Jordan, namely the Al-Karak (411 beds) and Al-Tafila (244 beds) hospitals.

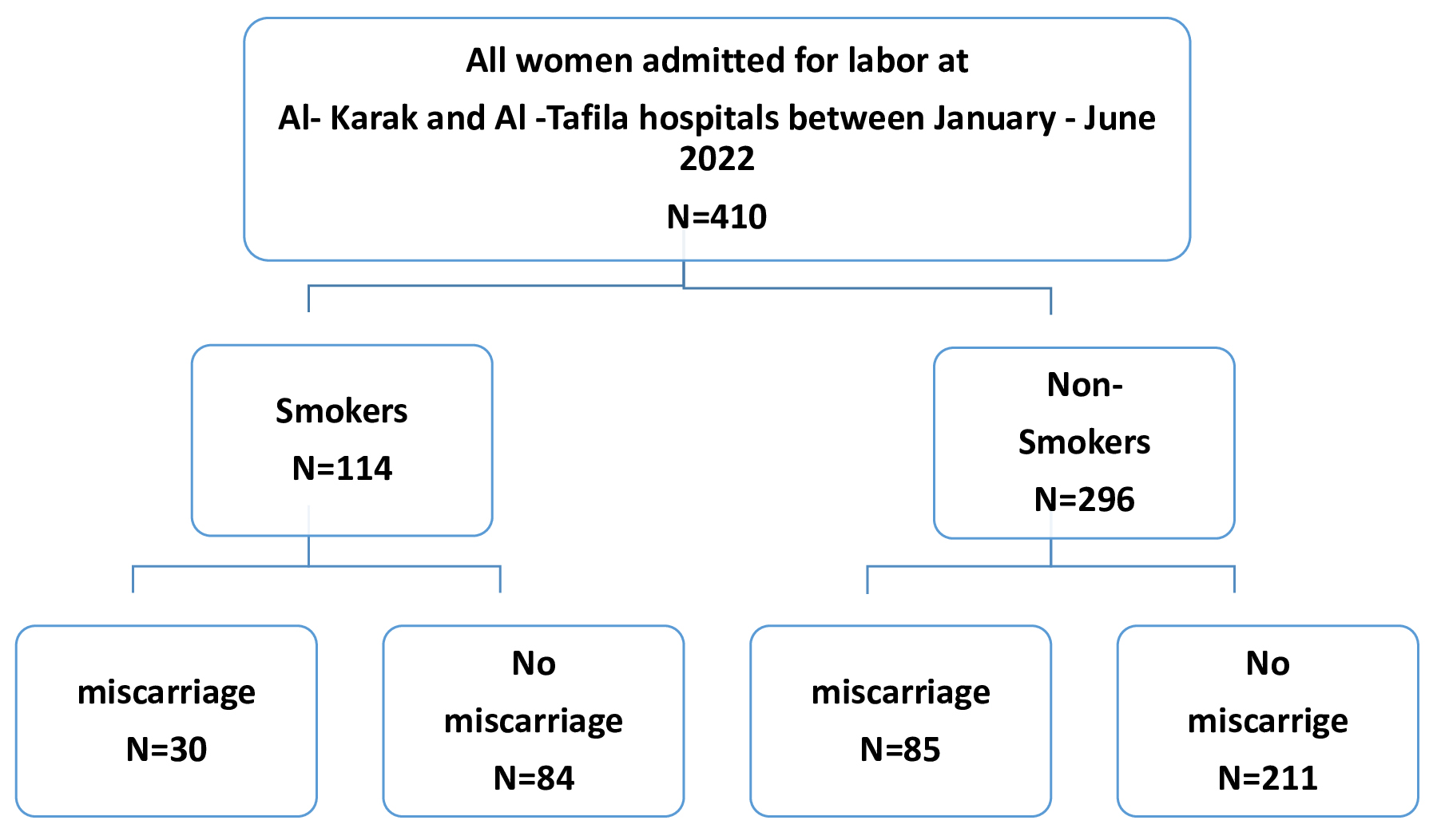

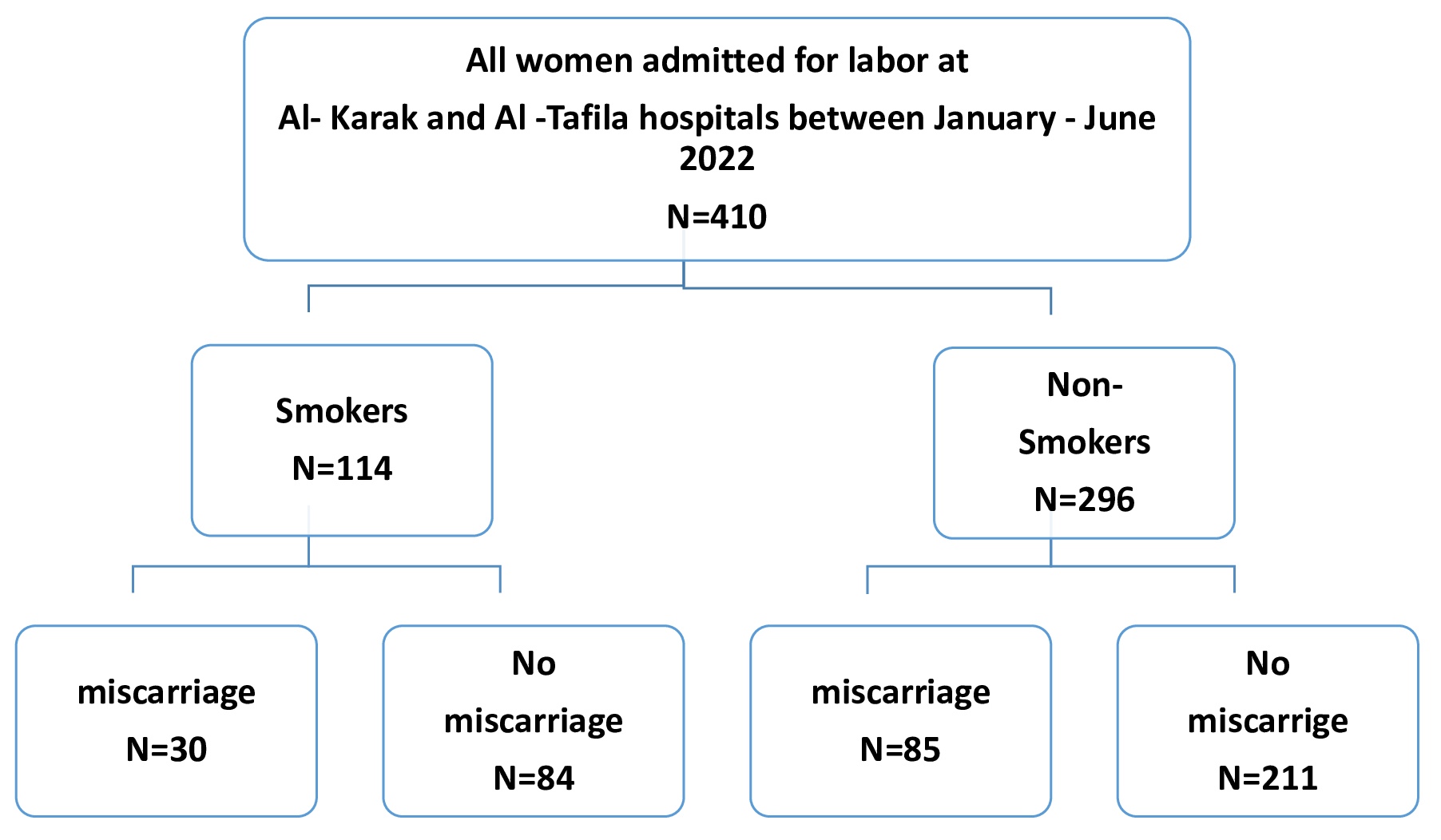

All women registered and admitted for labor at the delivery room in both hospitals during the study period were eligible for inclusion. The pregnant women were divided into two groups (smokers and non-smokers) at the time of delivery based on their response during evaluation. Currently active and passive smokers were classified as smokers. Smoking status was self-reported by the women during recording of their history. For the purpose of this study, the data on smoking was retrieved from medical records. Women were educated about the National Health Interview Survey (NHIS) definition of smoking. Those exposed to passive smoking were considered as smokers. Women were considered to be non-smokers when they did not meet the criteria of being a current smoker, a passive smoker, or an ex-smoker who quit either before or after becoming pregnant. Fig. 1 illustrates the inclusion process. This study was approved by the institutional review board (IRB) committee of our institute (No.1222023, Date 3.8.2023). Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. Patient data was anonymized to ensure the confidentiality of any identifiable information. This study conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Flow chart of the inclusion process.

Data extracted from the medical records included personal information, vital

signs, and newborn measurements. A data collection sheet was designed for the

study and included the following dichotomous categorical items: birth type

(vaginal delivery = 1, cesarean section = 2), previous miscarriages (no

miscarriage = 0, miscarriage = 1), birthweight (

Following data entry, statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical

Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 22 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Data were presented in tabular form (frequency and percentage) for the two study

groups. Cross-tabulation and the Chi-square test were used to detect significant

associations between the study variables and smoking, with Fisher’s exact test

used for low cell counts. Odds ratios (ORs) were calculated for variables showing

a significant association with smoking. The 95% confidence interval (95% CI)

was used to express uncertainty of results. A two-tailed p-value of

Included in this study were a total of 410 women with a mean age of 29.7

(standard deviation: 6.1) years. Of these, 296 (72%) were classified as

non-smokers and 114 as smokers. No significant difference in age was observed

between smokers and non-smokers. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical

characteristics of the smoking and non-smoking groups. Parity was significantly

different between the two groups, with 18% of non-smokers having parity

| Characteristic | Non-smoker, N = 296 |

Smoker, N = 114 |

p-value | |

| Age (years) | 29.7 (6.2) | 29.6 (5.9) | 0.8 | |

| Parity | ||||

| 0 | 2 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | ||

| 1–2 | 134 (45%) | 56 (49%) | ||

| 3–4 | 107 (36%) | 53 (46%) | ||

| 53 (18%) | 5 (4.4%) | |||

| Gestational age (weeks) | 36.6 (5.4) | 35.0 (5.5) | ||

| Apgar score | 7.87 (1.03) | 7.97 (0.99) | 0.4 | |

| Head circumference | 0.7 | |||

| 14 (4.9%) | 4 (3.8%) | |||

| 270 (95%) | 100 (96%) | |||

| History of miscarriage | 0.6 | |||

| Yes | 85 (29%) | 30 (26%) | ||

| No | 211 (71%) | 84 (74%) | ||

| Type of delivery | 0.051 | |||

| C-section | 145 (52%) | 42 (40%) | ||

| Vaginal | 136 (48%) | 62 (60%) | ||

| Birthweight (kg) | 0.004 | |||

| 35 (12%) | 25 (24%) | |||

| 250 (88%) | 79 (76%) | |||

| Labor | ||||

| Pre-term | 228 (79%) | 55 (49%) | ||

| Term | 62 (21%) | 58 (51%) | ||

SD, standard deviation; C-section, cesarean section.

The association between smoking and history of miscarriage was also examined

using a logistic regression model. As shown in Table 2, this analysis

showed no significant association between smokers and the risk of miscarriage

(OR: 1.22, 95% CI: 0.68–2.18, p = 0.50). Age was significantly

associated with a history of miscarriage (OR: 1.1, 95% CI: 1.0–1.12, p

= 0.004), while higher birthweight (

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence Interval (CI) | p | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Age | 1.071 | 1.0219 | 1.122 | 0.004 | |

| Parity | |||||

| 1–2 – 0 | - | - | - | - | |

| 3–4 – 0 | 0.789 | 0.4401 | 1.416 | 0.427 | |

| 1.385 | 0.633 | 3.03 | 0.415 | ||

| Smoking | |||||

| Smoker – Non-smoker | 1.223 | 0.6839 | 2.187 | 0.497 | |

| Gestational age | 0.868 | 0.7394 | 1.018 | 0.082 | |

| Apgar score | 1.19 | 0.8965 | 1.579 | 0.229 | |

| Type of delivery | |||||

| Vaginal – C-section | 0.691 | 0.4151 | 1.15 | 0.155 | |

| Birth weight | |||||

| 0.395 | 0.1917 | 0.813 | 0.012 | ||

| Labor | |||||

| Term – Pre-term | 0.27 | 0.0974 | 0.747 | 0.012 | |

| Head circumference | |||||

| 0.427 | 0.1444 | 1.26 | 0.123 | ||

The logistic regression model for the association between parity and study variables showed a significant association between lower Apgar score and patients with para 2 (OR: 1.89, p-value = 0.039). In addition, term deliveries were less likely associated with para 2 (OR: 0.24, p-value = 0.038). In women with para 3, there was a significant association with lower gestational age (OR: 0.75, p-value = 0.02), and vaginal deliveries were less likely seen in women with para 3 (OR: 0.39, p-value = 0.008), preterm deliveries were more likely to be associated with para 3 (OR: 0.23, p-value = 0.032). Lower gestational age was significantly associated with women with para 4 (OR: 0.76, p-value = 0.017), and term deliveries were less likely to be seen in para 4 (Table 3).

| Parity | Predictor | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | p-value | ||

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| 2 – 1 | Smoker: | |||||

| Smoker – Non-smoker | 0.515 | 0.2439 | 1.089 | 0.082 | ||

| Gestational age | 0.823 | 0.6443 | 1.052 | 0.12 | ||

| Head circumference | ||||||

| 0.421 | 0.07 | 2.526 | 0.344 | |||

| Apgar score | 1.896 | 1.099 | 3.648 | 0.039 | ||

| Type of delivery | ||||||

| Vaginal – C-section | 0.913 | 0.476 | 1.751 | 0.784 | ||

| Birth weight | ||||||

| 1.203 | 0.4723 | 3.066 | 0.698 | |||

| Labor: | ||||||

| Term – Preterm | 0.242 | 0.0637 | 0.922 | 0.038 | ||

| 3 – 1 | Smoker: | |||||

| Smoker – Non-smoker | 0.907 | 0.4357 | 1.888 | 0.794 | ||

| Gestational age | 0.749 | 0.5877 | 0.955 | 0.02 | ||

| Head circumference | ||||||

| 0.255 | 0.0479 | 1.354 | 0.109 | |||

| Apgar score | 2.429 | 0.3225 | 18.293 | 0.389 | ||

| Type of delivery | ||||||

| Vaginal – C-section | 0.388 | 0.1935 | 0.779 | 0.008 | ||

| Birth weight | ||||||

| 1.613 | 0.6236 | 4.173 | 0.324 | |||

| Labor: | ||||||

| Term – Preterm | 0.232 | 0.061 | 0.881 | 0.032 | ||

| 4 – 1 | Smoker: | |||||

| Smoker – Non-smoker | 0.672 | 0.3409 | 1.325 | 0.251 | ||

| Gestational age | 0.756 | 0.6007 | 0.952 | 0.017 | ||

| Head circumference | ||||||

| 0.639 | 0.0973 | 4.202 | 0.642 | |||

| Apgar score | 2.674 | 0.4211 | 16.977 | 0.297 | ||

| Type of delivery | ||||||

| Vaginal – C-section | 1.348 | 0.7256 | 2.506 | 0.344 | ||

| Birth weight | ||||||

| 1.396 | 0.5557 | 3.507 | 0.478 | |||

| Labor: | ||||||

| Term – Pre-term | 0.123 | 0.0336 | 0.448 | 0.001 | ||

The logistic regression model for the association between birth weight and study

variables showed a significant association between miscarriage and birth weight

in which mothers delivering babies with

| Birth weight | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | p-value | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Smoking: | |||||

| Smoker – Non-smoker | 0.7012 | 0.33941 | 1.449 | 0.338 | |

| Gestational age | 0.9834 | 0.81413 | 1.188 | 0.862 | |

| Apgar score | 1.2554 | 0.91115 | 1.73 | 0.164 | |

| Miscarriage | |||||

| No Miscarriage – Miscarriage | 2.4591 | 1.19052 | 5.079 | 0.015 | |

| Type of delivery | |||||

| Vaginal – C-section | 1.7036 | 0.844 | 3.439 | 0.137 | |

| Head circumference | |||||

| 0.9516 | 0.25161 | 3.599 | 0.942 | ||

| Labor | |||||

| Term – Pre-term | 0.0872 | 0.02877 | 0.264 | ||

The logistic regression model (Table 5) investigating the association between

labor and study variables showed a significant association between head

circumference and labor in which

| Labor | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | p-value | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||

| Apgar score | 1.0123 | 0.7567 | 1.354 | 0.935 | |

| Smoking: | |||||

| Smoker – Non-smoker | 4.1323 | 2.2722 | 7.515 | ||

| Birth weight: | |||||

| 0.0959 | 0.0468 | 0.196 | |||

| Type of delivery: | |||||

| Vaginal – C-section | 0.597 | 0.3325 | 1.072 | 0.084 | |

| Miscarriage: | |||||

| No Miscarriage – Miscarriage | 1.7004 | 0.8816 | 3.28 | 0.113 | |

| Head circumference: | |||||

| 0.2166 | 0.0686 | 0.684 | 0.009 | ||

This study estimated the prevalence of smokers and passive smokers amongst pregnant women in Southern Jordan. In addition, it investigated whether smoking in these women was associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. Finally, logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate the association between smoking and a history of miscarriage.

Although 26% of smoking women have had a history of miscarriage, we could not find a statistically significant association between smoking and miscarriage. These findings are in disagreement with those of Budani et al. [17], who reported a significantly higher rate of spontaneous miscarriage in women who were former smokers. Similarly, a systemic review conducted by Pineles et al. [18] found an increased rate of miscarriage in women who were active smokers, or who experienced second-hand smoking during pregnancy. George et al. [19] reported that pregnant women who were exposed to environmental tobacco smoke had a higher risk of spontaneous abortion than women who were not exposed (adjusted OR = 1.67). Furthermore, active smokers showed an elevated risk of spontaneous abortion compared to non-smokers.

The results of our study revealed that smoking during pregnancy was significantly associated with the risk of low birthweight. This finding agrees with those of other studies that reported associations between tobacco use during pregnancy and low birthweight, and with small fetus size during gestation [20, 21].

The current study found no significant association between the head circumference of infants and smoking by the mother during pregnancy. This is inconsistent with the results of an earlier study that found smoking during pregnancy was associated with a smaller head circumference (mean of 0.27 cm) compared to non-smoking mothers (pooled weighted mean difference = 0.27; 95% CI: 0.25, 0.29) [22]. This difference could be due to the small sample size in our study, and possibly also to ethnic differences.

The present study found no significant association between the Apgar score and

smoking during pregnancy. This may be due to the small sample size and the

inability to calculate the score in a small number of newly born infants. The

Apgar score is used to evaluate the health of newly born infants during the

immediate neonatal period, with a score of

Our results showed a significant association between pre-term delivery and

smoking during pregnancy, with a percentage of 49% (

This study investigated a crucial association between smoking in pregnant women and birth outcomes. The results demonstrate the need for more awareness amongst pregnant women in Jordan regarding the negative effects of smoking. Limitations of our study include the small sample size of both the case and control groups, the retrospective nature of data collection, the lack of data regarding body mass index, the inaccurate definition of smoking, the failure to use specific or non-specific smoking tests to validate the smoking and non-smoking groups, and the failure to consider other smoking alternatives such as the water pipe, e-cigarettes and vaping.

Future research should explore the mechanisms underlying the adverse effects of smoking on pregnancy outcomes. The impact of smoking cessation at different stages of pregnancy on birth outcomes should also be investigated with the aim of identifying critical windows for intervention. In addition, future studies should have larger sample sizes and a prospective design in order to minimize recall bias and improve the accuracy of classification for smoking. Possible effects of alternative smoking methods (e.g., vaping, water pipe) on pregnancy outcomes should also be investigated, given their increasing popularity. Finally, research into the role of paternal and household smoking will provide a better understanding of the impact of tobacco exposure on pregnancy and neonatal health.

In conclusion, the results of the present study revealed smoking during pregnancy might be related to birth outcomes including low birthweight, pre-term birth, miscarriage, head circumference and the Apgar score. However, we could not find any statistical significance when testing for direct association. Future studies should examine the effects of maternal smoking on the fetus in utero, the effects of maternal smoking during the three different trimesters of pregnancy, the effects of smoking cessation before and during the different trimesters of pregnancy, and the effects of passive and paternal smoking.

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

SA contributed to project development, data collection and management, data analysis, manuscript writing and editing. AA contributed to data collection, data analysis, manuscript writing. YH contributed to project development, data collection, manuscript writing. AZ contributed to data analysis, manuscript writing and editing. AALM contributed to data management, data analysis, manuscript editing. SM contributed to data collection, manuscript writing and editing. All authors contributed to the editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

This study was approved by the Mutah university institutional review board (IRB) committee at our institute (No.1222023, Date 3.8.2023). Informed consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. Patient data was anonymized to ensure the confidentiality of any identifiable information. This study conforms to the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki.

We express our gratitude to the obstetrics and gynecology departments at the Al-Karak and Al-Tafila hospitals for providing the resources and environment necessary to carry out this research. We also thank the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.