1 Division of Perinatology, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Basaksehir Cam and Sakura City Hospital, 34480 Istanbul, Turkey

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Basaksehir Cam and Sakura City Hospital, 34480 Istanbul, Turkey

3 Department of Pediatrics, Basaksehir Cam and Sakura City Hospital, 34480 Istanbul, Turkey

Abstract

Background: This study aimed to analyze prenatally diagnosed fetal

cardiac anomaly cases in a tertiary center with respect to the incidence, type of

anomalies, and rate of correct diagnosis based on postnatal diagnosis (by

comparing pre- versus post-natal diagnosis). Methods: In this

retrospective study, the data of 250 patients diagnosed with fetal cardiac

abnormalities who were evaluated in a perinatology department between January

2021 and May 2023 were analyzed. Results: A total of 250 cases were in

our study with a mean maternal age of 27.6

Keywords

- congenital heart disease

- prenatal diagnosis

- fetal therapy

Fetal cardiac anomalies are the most common cause of death among infants with congenital disabilities, affecting approximately 1% of newborns [1, 2, 3]. These conditions range from minor problems, such as ventricular septal defects that do not require intervention, to severe disorders, such as hypoplastic left heart syndrome, which can only be alleviated using palliative surgical procedures [4]. Early diagnosis and appropriate management, including prenatal interventions, are crucial for improving neonatal survival and long-term outcomes [5].

Congenital heart defects (CHD) can lead to critical neonatal complications and affect neurocognitive development if not addressed in time. Advances in prenatal diagnostic methods have improved our ability to detect severe CHD early, which is vital for planning necessary interventions in specialized centers and, in some cases, for making informed decisions about the termination of pregnancy [6].

Most cardiac anomalies diagnosed postnatally can be detected prenatally, with exceptions such as secundum atrial septal defects and patent ductus arteriosus [7]. Periodic assessment of the prevalence, clinical outcomes and family preferences of fetal cardiac anomalies is important to improve treatment strategies and fetal and infant care for fetal cardiac anomalies [8].

This study aimed to analyze prenatally diagnosed fetal cardiac anomaly cases in a tertiary center with respect to the incidence, type of anomalies, and rate of correct diagnosis based on postnatal diagnosis (by comparing pre- versus post-natal diagnosis).

The study was conducted with the permission of Basaksehir Cam and Sakura City Hospital Clinical Researches Ethics Committee (date: 02.10.2023, Decision No: 431). All the procedures were performed in accordance with the ethical rules and principles of the Declaration of Helsinki.

This retrospective study was conducted by evaluating 250 cases referred from an external center or diagnosed for the first time with prenatal CHD between January 2021 and May 2023 in the Perinatology Division of Cam and Sakura City Hospital. Our hospital serves as tertiary reference center for this region. Patients were systematically referred to our clinic for routine, comprehensive anatomical scans mandated by preliminary risk assessments performed in primary care or for specific suspicions of anomalies, including potential cardiac problems. All fetuses underwent a complete anatomical scan and standard echocardiography as well as color and pulsed Doppler, including color and pulsed wave Doppler examinations. All examinations were performed using an Arietta 850 ultrasound system (HITACHI, Tokyo, Japan). A team of perinatologists and pediatric cardiologists evaluated all fetuses in a joint meeting. Parents were informed about the significance of the diagnosis, the possibility of surgical or other treatment options after birth, expected short-term and long-term prognosis, and possibility of termination. Diagnoses were organized according to the International Pediatric and Congenital Cardiac Code (IPPCCC) [9]. All the patients were offered genetic analysis after consultation with the medical geneticist. The examination was repeated in some cases, if the first examination was incomplete and accurate heart disease could not be fully excluded. Postnatal definitive cardiac diagnoses were based on postnatal echocardiography, computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, cardiac catheterization, and intraoperative findings.

Maternal age, gestational week at diagnosis, the diagnosis before referral to our clinic, presence of substance abuse, presence of any drug use, and presence of chromosomal anomalies were recorded in detail. Since the study was retrospective and data from reported routine fetal echocardiography were used, informed consent was not obtained.

Data are presented as means with standard deviations, medians with ranges, and counts (%) as appropriate. All statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software (version 26; IBM SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA) for Windows.

A total of 250 patients with fetal cardiac anomalies were assessed at our center

with fetal cardiac anomalies during the study period. The demographic

characteristics of the patients, including maternal age, gravidity, parity, and

perinatal outcomes, are summarized in Table 1. The mean gestational age at first

evaluation at our center with the diagnosis of fetal cardiac anomaly was 27 weeks

(minimum 14 weeks, maximum 39 weeks) and the mean maternal age was 27.6

| Characteristic | Data | |

| Maternal age, years | 27.6 | |

| Gravidity, n | 2 (1–8) | |

| Gestational age at diagnosis, weeks | 27 (14–39) | |

| Multiple pregnancy, n (%) | 21 (8.4%) | |

| Maternal diseases | ||

| Pregestational/diabetes, n (%) | 7 (2.8%) | |

| Gestational diabetes, n (%) | 7 (2.8%) | |

| Hypothyroidism, n (%) | 13 (5.2%) | |

| Rheumatoid arthritis, n (%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Drug usage | ||

| Salicylic acid, n (%) | 4 (1.6%) | |

| Insulin, n (%) | 13 (5.2%) | |

| Thyroid hormone, n (%) | 12 (4.7) | |

| Previous child with congenital heart disease, n (%) | 3 (1.2%) | |

| Termination of pregnancy, n (%) | 15 (5.9%) | |

| Offered termination of pregnancy, n (%) | 49 (19.6%) | |

| Gestational age at termination of pregnancy, n | 23 (18–33) | |

| Fetal death, n (%) | 3 (1.2%) | |

| Extra-cardiac malformations | ||

| Single umbilical artery, n (%) | 3 (1.2%) | |

| Hydrops fetalis, n (%) | 4 (1.6%) | |

| Central nervous system system anomalies, n (%) | 6 (2.4%) | |

| Cystic hygroma, n (%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Limb anomalies, n (%) | 6 (1.6%) | |

| Multiple anomalies, n (%) | 4 (1.6%) | |

| Gastro-intestinal tract anomalies, n (%) | 5 (2.0%) | |

| Urinary tract anomalies, n (%) | 2 (0.8%) | |

| Thoracic abnormalities, n (%) | 1 (0.4%) | |

| Karyotype | ||

| Not known, n (%) | 201 (80.4%) | |

| Normal, n (%) | 34 (13.6%) | |

| Trisomy 21, n (%) | 9 (3.6%) | |

| Trisomy 18, n (%) | 3 (1.2%) | |

| Chromosome 22 microdeletion, n (%) | 3 (1.2%) | |

| Mode of delivery | ||

| Cesarean section, n (%) | 160 (74.4%) | |

| Vaginal delivery, n (%) | 55 (25.6%) | |

| Gestational age at birth | 36.7 | |

| Apgar score | ||

| at 1 min |

42 (28.0%) | |

| at 5 min |

12 (8.0%) | |

| Neonatal death, n (%) | 25 (16.6%) | |

A detailed anatomical examination of the studied fetuses showed a high rate (11.2%, 28/250) of non-cardiac anomalies, most commonly central nervous system and limb abnormalities (Table 1). Karyotype analysis and array tests were recommended for all cases diagnosed with fetal cardiac anomaly but were not performed in 80.4% (201/250) of the cases because the families declined these tests. In patients who underwent karyotype analysis, the most common genetic abnormality was trisomy 21, with a rate of 3.6% (9/250). Other chromosomal abnormalities included three cases of trisomy 18 and three cases microdeletion of chromosome 22 (Table 1). Intrauterine fetal death occurred in three cases of fetal congenital heart disease, atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD), ventricular septal defect (VSD), and tricuspid valve insufficiency. Among these cases, the karyotype result of one case with tricuspid valve insufficiency was trisomy 21 and the karyotype result of the other case with VSD was normal. The option to terminate pregnancy was extended to 19.6% (49/250) of individuals who displayed abnormal karyotype analysis, severe extracardiac anomalies, or severe congenital heart diseases. Of these individuals, 5.9% them (15/250) opted to terminate their pregnancy. The termination of these 15 pregnancies was performed at an average gestational age of 23 weeks, ranging from 18 to 33 weeks. No autopsy was performed that were terminated. The most prevalent fetal cardiac anomaly was membranous ventricular septal defects (VSD) with a rate of 14.8% (37/250). Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS) was the next most common anomaly (10.8%, 27/250), followed by atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD) (8.4%, 21/250) and double outlet right ventricle (DORV) (7.6%, 19/250).

Table 2 presents the spectrum and frequency of defects observed in fetuses diagnosed with fetal cardiac anomalies. Fetal supraventricular tachycardia was observed in eight cases; the mothers of five of them were treated prenatally with digoxin and flecainide, hospitalized and followed up regularly.

| Type of cardiac defect, n (%) | Number of cases |

| Membranous ventricular septal defect (VSD) | 37 (14.8%) |

| Hypoplastic left heart syndrome (HLHS), n (%) | 27 (10.8%) |

| Atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD), n (%) | 21 (8.4%) |

| Double outlet right ventricle (DORV), n (%) | 19 (7.6%) |

| Transposition of the great arteries (TGA), n (%) | 18 (7.2%) |

| Tetralogy of Fallot (TOF), n (%) | 18 (7.2%) |

| Aortic arch hypoplasia, n (%) | 15 (6.0%) |

| Musculer ventricular septal defect, n (%) | 14 (5.6%) |

| Tricuspid regurgitation, n (%) | 12 (4.8%) |

| Pulmonary stenosis/atresia, n (%) | 11 (4.4%) |

| Right aortic arch, n (%) | 9 (3.6%) |

| Fetal supraventricular tachycardia, n (%) | 8 (3.2%) |

| Persistent left superior vena cava, n (%) | 6 (2.4%) |

| Aortic stenosis, n (%) | 5 (2.0%) |

| Right ventricular hypoplasia, n (%) | 3 (1.2%) |

| Tricuspid atresia, n (%) | 3 (1.2%) |

| Aberrant right subclavian artery (ARSA), n (%) | 3 (1.2%) |

| Truncus arteriosus, n (%) | 3 (1.2%) |

| Cardiomyopathy, n (%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Double inlet left ventricle (DILV), n (%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Isolated interrupted inferior vena cava (IIVC), n (%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Left atrial isomerism, n (%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC), n (%) | 2 (0.8%) |

| Corrected transposition of great arteries (L-TGA), n (%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Left ventricle hypoplasia, n (%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Coarctation of aorta (CoA), n (%) | 1 (0.4%) |

| Situs inversus, n (%) | 1 (0.4%) |

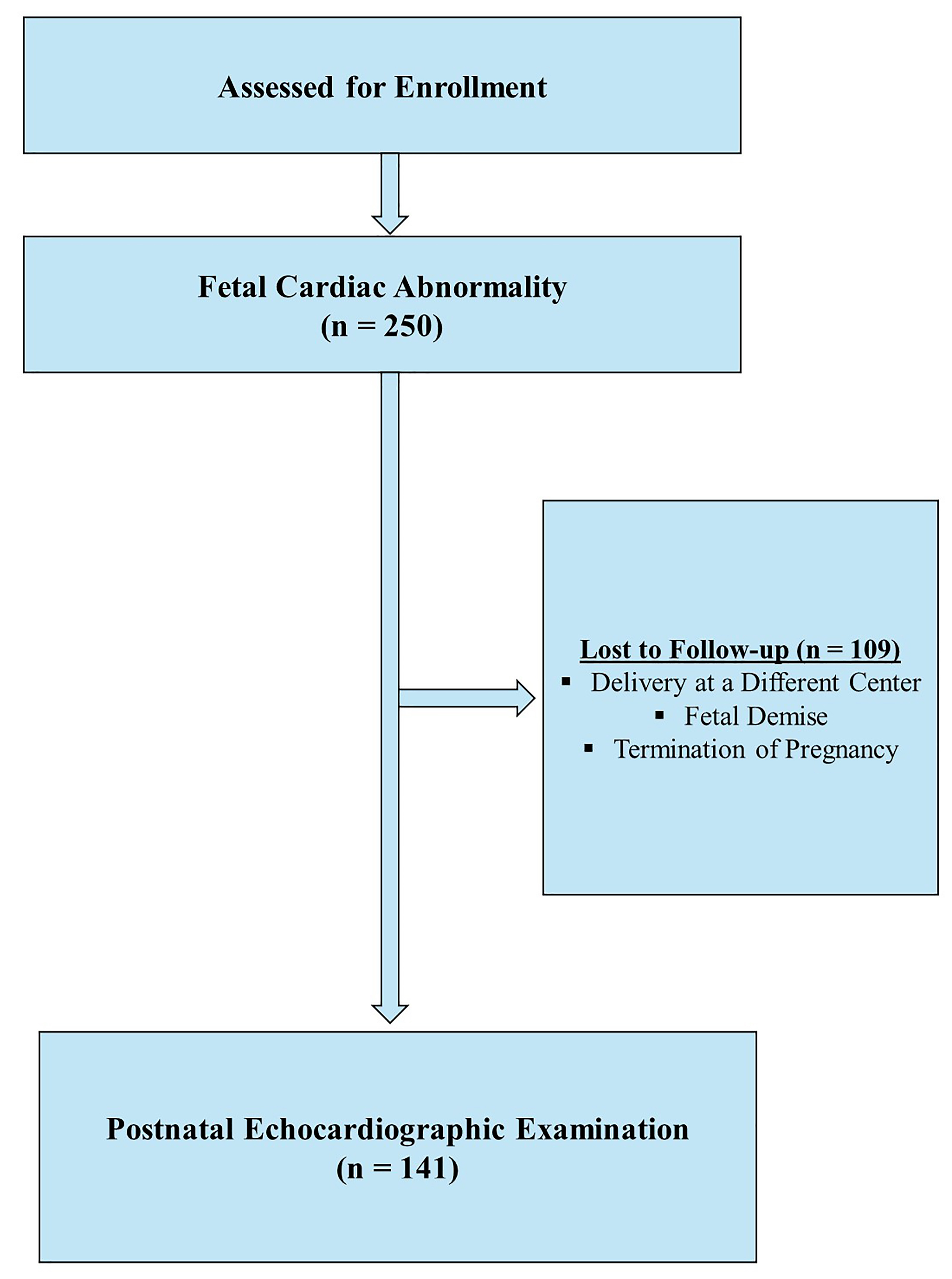

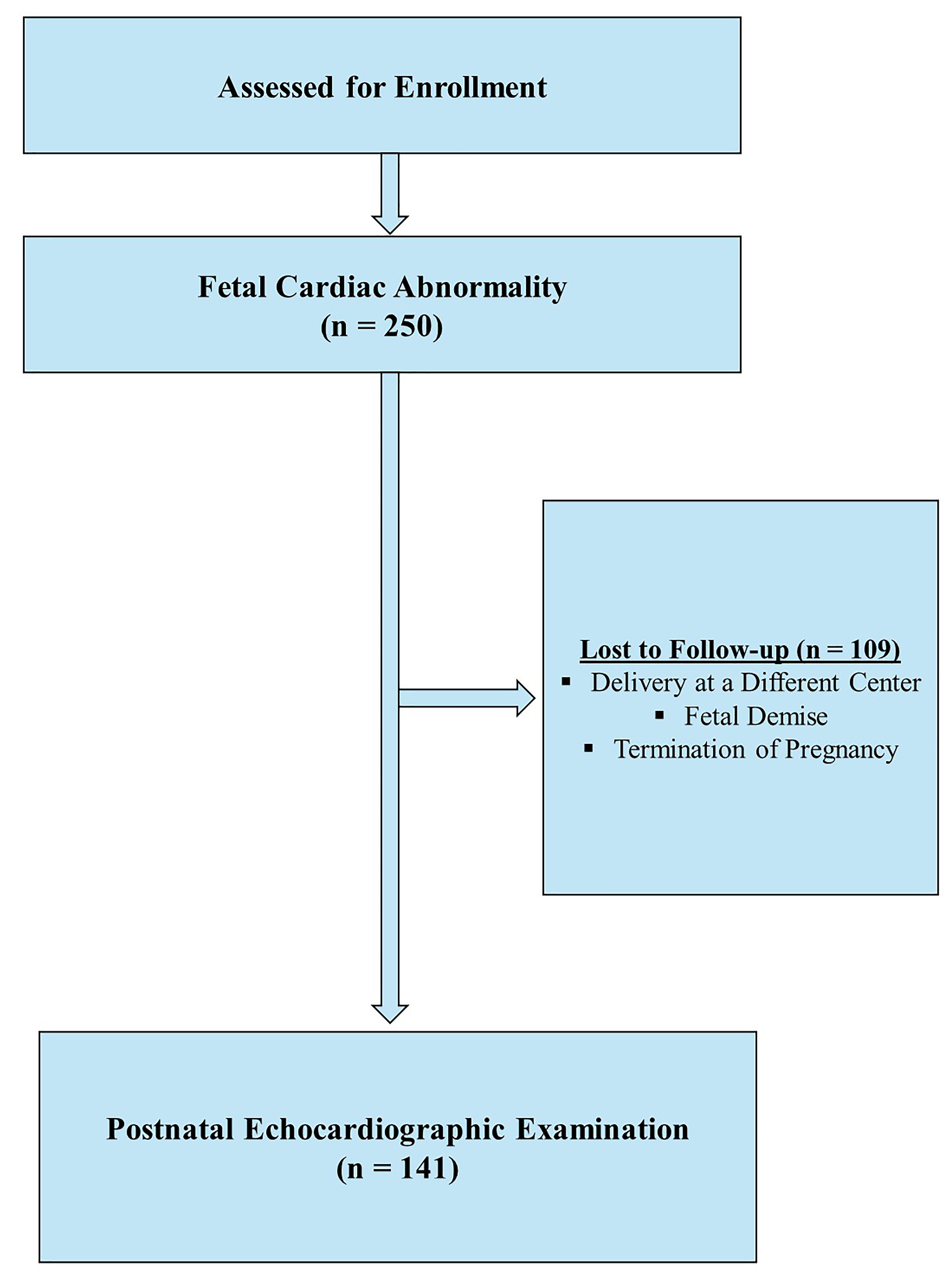

Postnatal echocardiographic examinations were performed in 141 cases and 109

cases were lost to follow-up because of delivery at a different center, referral

of the newborn after delivery, fetal death, or termination of pregnancy (Fig. 1). The

median postoperative follow-up of live births was 2.2 years, range 2 weeks to 3

years. When we compared these postnatal examinations with prenatal diagnosis, we

found that the diagnosis changed in 40 cases. Discrepancies between prenatal and

postnatal diagnoses are shown in Table 3. Fetal muscular ventricular septal

defect, ventricular septal defect and double outlet right ventricle were the most

frequently misdiagnosed fetal cardiac anomalies according to postnatal

echocardiographic diagnoses. The accuracy rate for prenatal and postnatal

diagnoses was 71.63% (101/141). The mean gestational age of the study population

with different prenatal and postnatal diagnoses was approximately 27 weeks,

whereas that of the study population with the same diagnosis was approximately 28

weeks. The mean gestational age was similar in cases with concordant and

discordant prenatal and postnatal diagnoses (p

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Flowchart of the study.

| Prenatal diagnosis | Postnatal diagnosis |

| Aortic arch hypoplasia (n = 2) | Patent ductus arteriosus |

| Coarctation of aorta (n = 1) | Aortic arch hypoplasia |

| Muscular ventricular septal defect (n = 7) | Patent ductus arteriosus (n = 2) |

| Atrial septal defect (ASD) (n = 1) | |

| Ventricular septal defect (n = 2) | |

| Pulmonary stenosis/atresia (n = 2) | - |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | Pulmonary stenosis/atresia |

| Right aortic arch (n = 2) | - |

| Tetralogy of Fallot (n = 3) | Double outlet right ventricle |

| Pulmonary stenosis/atresia | |

| Ventricular septal defect | |

| Aortic stenosis (n = 2) | Aortic arch hypoplasia |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | |

| Ventricular septal defect (n = 6) | Pulmonary stenosis/atresia |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | |

| Atrioventricular septal defect | Ventricular septal defect |

| Transposition of the great arteries (n = 3) | Double outlet right ventricle |

| Truncus arteriosus | Corrected transposition of great arteries |

| Right ventricular hypoplasia | Double inlet left ventricle |

| Double outlet right ventricle (n = 4) | Double inlet left ventricle |

| Tetralogy of Fallot | |

| Transposition of the great arteries (n = 2) | |

| Fetal supraventricular tachycardia (n = 2) | Mitral regurgitation |

| Patent ductus arteriosus | |

| Left ventricle hypoplasia | - |

| Isolated interrupted inferior vena cava (IIVC) | Persistent left superior vena cava |

This retrospective analysis of 250 cases of fetal cardiac anomalies managed at our perinatology center provides significant insights into the diagnosis, management, and outcomes of congenital heart defects (CHDs). The results of this study have drawn attention to the fact that the prenatal and postnatal management of pregnancies with prenatal fetal cardiac anomalies may vary considerably and that caution should be exercised during the follow-up of these pregnancies. Our study revealed that the mean gestational age at which fetal cardiac anomalies were diagnosed was approximately 27 weeks, with diagnoses made as early as 14 weeks and as late as 39 weeks. The optimum schedule for screening fetal CHDs with echocardiography is typically between 18 and 22 weeks of pregnancy. However, some defects may not be apparent or manifest until the later gestational weeks. In addition, increased sonographer experience and ultrasound sensitivity are crucial for detecting CHDs. The lack of availability of experienced sonographers and highly sensitive ultrasound devices at the antenatal care stage might cause a delay in diagnosis and referral for antenatal screening. These factors contributed to the wide range of gestational weeks at diagnosis [10, 11, 12].

Our findings showed a prenatal and postnatal diagnosis concordance rate of 71.63%. This aligns with previous studies that have demonstrated variability in detection rates and the importance of technological advances in improving diagnostic accuracy. Trivedi et al. [7] reported a rate of 81.7% in their study which is close to our work. Although this was done in recent years, a higher rate (96%) was found in the studies by Davis et al. [13]. According to Mamalis et al. [14], prenatal and postnatal echocardiography had a “near-perfect” diagnostic agreement in detecting congenital heart defects, with sensitivity and specificity rates ranging from 88% to 100% and 97% to 100%, respectively.

While there were cases in which the diagnosis changed after birth, the mean diagnostic week did not significantly differ between concordant and discordant cases.

A detailed fetal anatomical scan of all cases of fetal cardiac anomalies revealed that 11.2% (28/250) of the cases presented non-cardiac anomalies, most commonly central nervous system and limb abnormalities. Moreover, genetic testing, including karyotype analysis and array tests, was recommended for all cases, but declined by 80.4% (201/250) of families. Social and cultural barriers, and the unwillingness of parents to terminate pregnancy if a positive diagnosis is made are the main causes of low rates of prenatal genetic testing.

The option to terminate pregnancy was offered to 19.6% of the individuals who displayed abnormal karyotype analysis, severe extracardiac anomalies, or severe congenital heart disease. Of these, 5.9% opted for termination at an average gestational age of 23 weeks. The availability of this option underscores the complex decisions that parents face when confronted with challenging fetal diagnoses, and highlights the importance of comprehensive counseling and support throughout the decision-making process.

In our cohort, intrauterine fetal death occurred in three cases with significant cardiac anomalies. These include atrioventricular septal defect (AVSD), membranous ventricular septal defect (VSD), and tricuspid valve insufficiency. In one case, tricuspid valve insufficiency was associated with trisomy 21, a known risk factor for increased mortality due to hemodynamic instability. In another case, a normal karyotyped fetus with a membranous VSD succumbed, which might suggest the severity of the defect or the presence of other undetected complications such as arrhythmias or myocardial dysfunction leading to fetal demise.

Our study revealed membranous VSD was the most prevalent congenital cardiovascular system abnormality (14.8%), followed by HLHS (10.8%), AVSD (8.4%), and DORV (7.6%). This information is of great significance to healthcare providers and researchers as it reveals the relative prevalence of different CHDs within the population under investigation. Özbarlas et al. [15] reported that, membranous VSD was the most commonly detected congenital heart disease. Similarly, Ece et al. [16] found VSD to be the most prevalent cardiac anomaly in their study.

No intrauterine interventional procedures were performed when our study evaluated prenatal interventions or medical treatments. However, in five cases, the mother was hospitalized due to fetal supraventricular tachycardia, and medical treatment was administered. In recent years, fetal interventional procedures have been widely used in cases of pulmonary atresia and aortic stenosis [17]. Although balloon dilatation was planned for fetal aortic stenosis in our clinic, intrauterine fetal intervention could not be performed in our center because of the lack of cases that met the appropriate criteria.

Although our hospital is a tertiary referral center, the postnatal follow-up rate was incredibly low (56.4%, 141/250). The major reasons for the low follow-up rate might be the delivery of the fetus at a different center, referral of the newborn after delivery, fetal death, or cases that opted for termination of pregnancy.

The current investigation provides strong evidence that a detailed ultrasound examination of the fetal heart can identify of more than 2/3 of fetuses complicated by major cardiac pathology. In addition, a systematic approach to these abnormalities aids in identifying the accurate diagnosis of isolated cardiac defects, connected with other systems or a part of a syndrome. A comprehensive examination of anatomical scans may play a crucial role in enhancing diagnostic accuracy. According to the existing data and uncertainty concerning accurate diagnosis, the procedure following a positive screening scan should be expert fetal cardiac ultrasound follow-up. These findings contribute to our understanding of CHDs in terms of the incidence, type of anomalies, and rate of correct diagnosis based on postnatal diagnosis.

All data are available upon request as supplementary files. Please contact the corresponding authors for further information.

GB, ITB, MC, HTK and NBC designed the research study. GB, ITB, MC, HTK and NBC performed the research. GB, ITB analyzed the data. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The procedures followed the ethical guidelines of the responsible committee on human experimentation and the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its amendments. Given the retrospective nature of the study, the requirement for informed consent was waived. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Basaksehir Cam and Sakura City Hospital (date: 02.10.2023, Decision No: 431).

We would like to express our gratitude to all those who helped us during the writing of this manuscript. Thanks to all the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.