1 Department of Gynaecology, Wuhu Hospital Affiliated to East China Normal University, 241000 Wuhu, Anhui, China

2 Department of Gynaecology, The First Affiliated Hospital of Wannan Medical College, 241001 Wuhu, Anhui, China

3 Department of Radiation, The First Affiliated Hospital of Bengbu Medical University, 233099 Bengbu, Anhui, China

Abstract

Background: There is much controversy about the utility of open and

laparoscopic surgery procedures for cervical cancer following the Laparoscopic

Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial. The main objective of this study was to

determine the utility of laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy (LNSRH)

in improvement of postoperative bladder and rectal function and clinical outcomes

of patients with common types of early-stage cervical cancer and tumor diameters

Keywords

- abdominal radical hysterectomy

- early-stage cervical cancer

- laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy

- pelvic autonomic nerve

- survival outcomes

Cervical cancer is the most common gynecologic tumor type and has one of the

highest morbidity and mortality rates among female malignancies worldwide [1].

The World Health Organization (WHO) officially released “The Global Strategy to

Accelerate the Elimination of Cervical Cancer” in November 2020 [2]. Surgery is

one of the main modes of treatment for early-stage cervical cancer and National

Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines recommend radical open

hysterectomy with bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy [3]. Laparoscopy, which

enables a precise operation as well as identification and selective sparing of

pelvic and abdominal nerves, resulting in an improved postoperative quality of

life. By 2018, owing to the advantages of less trauma and faster recovery of

patients, the procedure was widely adopted on a global scale. In 2018, the New

England Journal of Medicine published a randomized controlled trial of the

Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) conducted at M.D. Anderson Cancer

Center in the United States [4] as well as the results of a real-world study

(RWS) conducted at the Harvard Medical School [5]. These articles highlighted

higher mortality and recurrence rates of cervical cancer patients undergoing

minimally invasive surgery. Disease-free survival (DFS) and overall survival (OS)

rates were poorer in these patients relative to those subjected to open surgery.

However, the LACC study indicated that the results were not applicable to

low-risk cervical cancer patients with tumor diameters

This study was approved by the ethics committee of the Second People’s Hospital of Wuhu (the Second People’s Hospital of Wuhu was renamed Wuhu Hospital affiliated to East China Normal University in 2020) (approval number: MER-2019-07-15). All subjects provided informed consent prior to participation. Procedures were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Ninety patients with cervical cancer admitted to the Department of Gynecology of Wuhu Hospital (affiliated with East China Normal University and the First Affiliated Hospital of Wannan Medical University) from January 2015 to January 2021 were selected for the study, including 45 who underwent laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy (LNSRH) as the study group and 45 who underwent traditional ARH as the control group. This study was a retrospective non-randomized design. The patients underwent the surgery they preferred after being informed of the risks and benefits of each procedure. Participants were enrolled according to the mode of operation.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: ① age

LNSRH was performed in the study group as follows: after successful anesthesia, a puncture was induced with the laparoscopic trocar to form an artificial pneumoperitoneum. The puncture was made 2 cm above the pubic symphysis in the midline of the abdomen using 0.5 cm trocar. A needle holder was inserted to suture the bottom of the uterus in a figure of eight loop. The needle holder clamp coil was used to adjust the position of the uterus for performance of the LNSRH. Four key steps were followed for nerve preservation. (A) The inferior hypogastric nerve is situated below the ureteral mesangium on the lateral side of the sacrospinous ligament. During surgery, Ganglin’s gap was initially separated, following which the sacrospinous ligament was cut after pushing the inferior hypogastric nerve outward. (B) The bladder and rectal side gaps were separated, the cardinal ligament exposed, and uterine artery and the deep uterine vein identified. Next, the uterine artery was ligated at the root, the deep uterine vein ligated 1 cm away from the internal iliac vein, the bladder branch ligated, the deep uterine vein and uterine artery turned laterally toward the body of the uterus, and the pelvic visceral nerve below the deep uterine vein preserved. (C) The anterior lobe of the vesico-cervical ligament was cut, the posterior lobe of the vesico-cervical ligament separated, the superior and middle vesical veins exposed, the blood vessel ligated, and nerve tissue below the blood vessel preserved. (D) Next to the cervix and below the deep uterine vein, the hypogastric nerve (HN) within the lateral rectal ligament intersects with the pelvic splanchnic nerve (PSN) within the cardinal ligament to form the inferior hypogastric plexus (IHP). The uterine and bladder branches innervated by the inferior hypogastric plexus were carefully identified. The uterine branch was cut and bladder branch retained. Nerve fibers of the bladder branch were pushed outward. The tissue around the vagina was excised. The vagina was ringed with a lasso 3 cm below the cervical or vaginal tumor to isolate neoplastic foci, followed by incision of the vagina and suture below the lasso. The remaining surgical steps were the same as those used in a traditional abdominal radical hysterectomy.

ARH was performed in the control group as follows: pelvic lymph node dissection was initially conducted according to the standard procedure, followed by radical hysterectomy through the abdomen [8].

Comparison of age, FIGO clinical stage, pathologic type and body mass index

(BMI) of the two groups revealed no significant differences (p

| Characteristics | LNSRH group (n = 45) | ARH group (n = 45) | p value | |

| Age (years) | 54.44 |

53.58 |

0.665 | |

| BMI (kg/m |

21.47 |

21.42 |

0.767 | |

| Tumor stage (cases) | 0.796 | |||

| IB1 | 36 | 35 | ||

| IIA1 | 9 | 10 | ||

| Pathologic type (cases) | 0.940 | |||

| Squamous carcinoma | 39 | 40 | ||

| Adenocarcinoma | 5 | 4 | ||

| Adenosquamous carcinoma | 1 | 1 | ||

Abbreviations: LNSRH, laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy; ARH, abdominal radical hysterectomy; BMI, body mass index.

The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) [9] was used to assess the degree of pain in patients at 8, 24 and 48 hours after surgery, with scores ranging from 1 to 10. Higher scores were indicative of a more severe degree of pain.

Attempts were made to remove the urinary catheter 1 week after surgery in the two groups of patients. In cases where the patient was unable to urinate or the residual urine volume in the bladder detected with ultrasound was greater than 100 mL, the catheter was retained and removed every three days until the residual urine volume was less than 100 mL. Catheter retention time and postoperative urinary symptoms, such as frequent and urgent urination, incontinence, dysuria and abdominal pressure urination, were recorded for both groups.

The time to first postoperative flatus and defecation and postoperative digestive symptoms, such as constipation and diarrhea, were recorded to evaluate the recovery of rectal function.

Urodynamic parameters of the two groups before and 12 months after surgery, including maximum flow rate (MFR), average flow rate (AFR), initial urinary bladder volume, maximum urinary bladder volume and maximum detrusor pressure (MDP), were compared.

Patients were followed up by telephone, Wechat and return visits over a period of 27–80 months. The surgeons maintained contact with patients after surgery and provided guidance regarding lifestyle and medical treatments.

SPSS 26.0 statistical software (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was employed for

data processing. Measurement data were expressed as mean

We observed no significant differences in the amount of blood loss, number of

dissected lymph nodes, length of vaginal resection and length of parametrial

resection between the two groups. However, the operation time for LNSRH was

significantly longer than that for ARH (p

| Parameters | LNSRH group (n = 45) | ARH group (n = 45) | p value | |

| Operation time (min) | 235.76 |

185.71 |

||

| Amount of bleeding (mL) | 249.33 |

243.11 |

0.607 | |

| Number of lymph nodes | 28.38 |

28.60 |

0.895 | |

| Length of parametrial resection (cm) | 3.12 |

3.10 |

0.670 | |

| Length of vaginal resection (cm) | 2.89 |

2.98 |

0.088 | |

| Postoperative indwelling catheter time (days) | 10.56 |

19.76 |

||

| First flatus (hours) | 32.62 |

57.56 |

||

| First spontaneous defecation time (hours) | 40.16 |

60.20 |

||

| Recovery 6 months after surgery | ||||

| Dysuria | 3 (6.7%) | 13 (28.9%) | 0.006 | |

| Abdominal pressure urination | 7 (15.6%) | 18 (40.0%) | 0.01 | |

| Incomplete urination | 4 (8.9%) | 14 (31.1%) | 0.008 | |

| Constipation | 4 (8.9%) | 11 (24.4%) | 0.048 | |

| Prolonged urination time | 4 (8.9%) | 13 (28.9%) | 0.029 | |

Abbreviations: LNSRH, laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy; ARH, abdominal radical hysterectomy.

VAS scores were significantly different at 8, 24 and 48 hours between the two

groups, with lower scores obtained for the study group relative to the control

group (p

| VAS scores | LNSRH group (n = 45) | ARH group (n = 45) | p value |

| 8 hours after surgery | 3.11 |

4.27 |

|

| 24 hours after surgery | 2.04 |

3.04 |

|

| 48 hours after surgery | 1.02 |

1.96 |

|

| p value |

Abbreviations: VAS, Visual Analogue Scale; LNSRH, laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy; ARH, abdominal radical hysterectomy.

Postoperative indwelling catheter retention time, first time of flatus and

spontaneous defecation time of the two groups were significantly different

(p

Urodynamic parameters of the two groups were comparable before surgery

(p

| Parameter | LNSRH group (n = 45) | ARH group (n = 45) | p value | |

| Maximum flow rate (MFR) (mL/s) | ||||

| Pre-operation | 23.63 |

23.18 |

p | |

| 12 months after surgery | 23.59 |

p | ||

| Average flow rate (AFR) (mL/s) | ||||

| Pre-operation | 9.36 |

9.24 |

p | |

| 12 months after surgery | 8.95 |

p | ||

| Initial urinary bladder volume (mL) | ||||

| Pre-operation | 184.38 |

183.56 |

p | |

| 12 months after surgery | 184.60 |

p | ||

| Maximum urinary bladder volume (mL) | ||||

| Pre-operation | 357.11 |

365.27 |

p | |

| 12 months after surgery | 357.27 |

p | ||

| Maximum detrusor pressure (cmH |

||||

| Pre-operation | 51.01 |

49.82 |

p | |

| 12 months after surgery | 50.82 |

p | ||

Note: a) 12 months after surgery, p

Abbreviations: LNSRH, laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy; ARH, abdominal radical hysterectomy.

After surgery, a number of patients from both groups received additional

chemotherapy and radiation therapy. Sedlis criteria were used to determine

whether adjuvant therapy was required [3]. Postoperative treatment of patients

with cervical adenocarcinoma or adenosquamous carcinoma was additionally based on

the “four-factor model” [10]. Tumor tissue samples were obtained from the

cervix and parametrial areas of invasion. Samples were fixed and stained with

hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) to investigate the presence of perineural invasion

(PNI). This represents a condition whereby tumor cells gather and wrap around

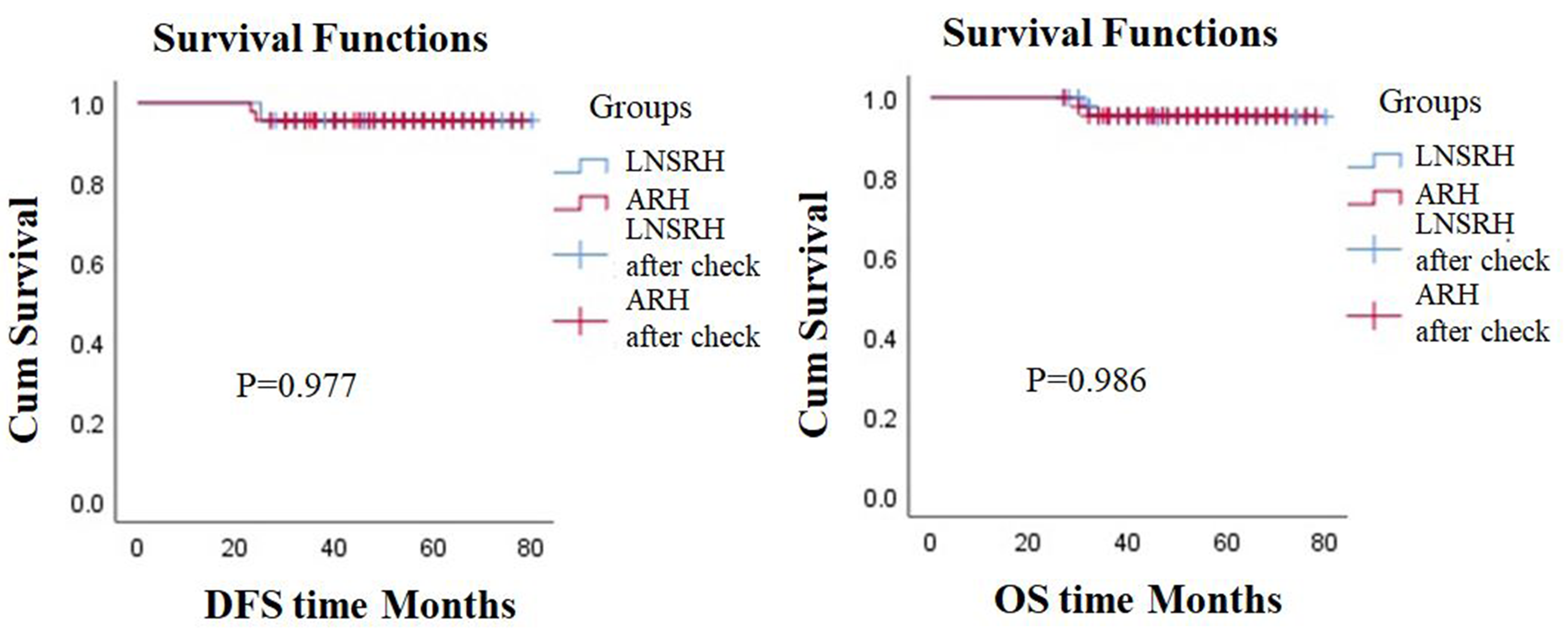

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.Survival curves of the two groups. LNSRH, laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy; ARH, abdominal radical hysterectomy; DFS, disease-free survival; OS, overall survival.

The present study evaluated the utility of laparoscopic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy as a minimally invasive procedure associated with less trauma, reduced pain, and a lower impact on vesical and intestinal function that could promote more rapid postoperative recovery. Stringent surgical criteria must be met for LNSRH, requiring surgeons with extensive experience in laparoscopic surgery to identify the nerves in the pelvic cavity. Ye et al. [12] considered the application of deep uterine and bladder veins as potential markers of nerve-sparing surgery. The Li et al. [13] demonstrated that water-jet dissection of the IHP during LNSRH could restore normal urodynamics more rapidly without affecting survival outcomes. Previous studies recommended the optimal use of non-energy or low-energy surgical instruments and an ultrasonic scalpel in combination with a vascular clip to avoid electrothermal injury in surgery for cervical cancer with pelvic autonomic nerve preservation [14]. In the LNSRH group, a self-made intraperitoneal irrigation device with moderate pressure was used to repeatedly wash and separate connective tissue surrounding the nerves to facilitate exposure. Endoscopic vascular clips, such as Hemolok or titanium clips, were used to ligate blood vessels around the nerve to ensure preservation, following which the blood vessels were cut. This not only avoided thermal damage to pelvic nerves, but also reduced intraoperative bleeding and favored postoperative recovery of bladder and rectum function. The operative time for LNSRH was significantly longer than that for ARH due to the need for delicate surgical identification of the protective nerves.

The sympathetic nerve fibers of the IHP innervate the bladder to store urine while the parasympathetic nerve fibers innervate the bladder for release of urine. Parasympathetic nerve injury leads to voiding dysfunction, representing the main cause of long-term bladder dysfunction [15]. Damage to the rectal branches from IHP can cause delayed defecation and passage of flatus. Urodynamic examination provides objective measurements of bladder dysfunction [16]. Initial and maximum bladder capacity of urinary urgency reflect sympathetic nerve damage, while MFR, MDP and abdominal pressure during urination reflect parasympathetic nerve damage. Notably, the reported post-surgical incidence of urinary system dysfunction is 25–47%. Therefore, surgery with pelvic autonomic nerve preservation is highly beneficial for patients with cervical cancer [17]. Our study demonstrated that urodynamic parameters in the LNSRH group recovered to preoperative levels at 12 months after surgery, but not in the ARH group. A potential explanation for this finding is that sympathetic and parasympathetic nerve injuries occurred during the operation, resulting in abdominal pressure urination, difficulty in defecation and other symptoms in the ARH group. The results support the conclusion that LNSRH is more beneficial for the recovery of bladder and rectal function in patients with early cervical cancer.

Previous studies suggest that preservation of nerve-connected parametrial tissue

during cervical cancer surgery can lead to PNI and the possibility of tumor

residual, which poses a high risk of recurrence. Therefore, nerve-sparing surgery

should be cautiously performed on patients with smaller tumors. A study by Wei

et al. [18] analyzed 174 patients with early-stage cervical cancer who

underwent open radical hysterectomy (ORH), LRH and LNSRH. Overall, PNI-positive

patients had lower DFS and OS than PNI-negative patients, which was not related

to surgical type. In this study, several patients with PNI were included in both

groups. However, survival outcomes were not significantly different between the

groups. Previous research indicated that survival outcome of PNI is not

independently associated with the type of surgery. Another report suggested that

the poor oncological outcomes of minimally invasive surgery (MIS) could be

attributable to the use of the uterine manipulator, CO

Several limitations of our study should be taken into consideration that may

affect data interpretation. First, we did not perform sub-analyses for histology

and grading of cervical cancer. The effects of two types of radical hysterectomy

on survival and quality of life in patients with early cervical cancer were

compared. In the cervical cancer guidelines prior to 2023, radical hysterectomy

is the standard procedure recommended for patients with stage IB1 and IIA1

disease [3]. The 2023 NCCN Guidelines recommend extrafascial hysterectomy plus

pelvic lymphadenectomy (or sentinel lymph node (SLN) mapping) for stage IA2–IB1

cervical carcinoma (based on cone biopsy and meeting all the criteria for

conservative surgery) [21]. The criteria for conservative surgery include no

lymph-vascular space invasion (LVSI), negative cone margins, squamous cell (any

grade) or usual type adenocarcinoma (grade 1 or 2 only), tumor size

Laparoscopic pelvic autonomic nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy has beneficial effects on patients with common pathologic types of early-stage cervical cancer and small tumors. The method can effectively improve the postoperative bladder and rectal function of patients and facilitate rapid recovery without exerting adverse effects on survival outcomes. However, the number of cases included in this current study is relatively small and further clinical trials on a larger scale are necessary to validate the efficacy and safety of LNSRH.

The data that support this study will be shared upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

HX designed the research study. HX and SL performed the experimental procedures. HX participated in analyzing data, drafting the manuscript, and reviewing and proofreading papers. SL collected some of the patient data and completed follow-up of these patients. MC participated in performance of the operation, patient follow-up, and collection and analysis of data. YZ conducted analysis of data. All authors contributed to editorial changes, read and approved the final manuscript, participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the content.

All subjects provided informed consent for inclusion in the study. This research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the protocol was approved by the ethics committee of the Second People’s Hospital of Wuhu (the Second People’s Hospital of Wuhu was renamed Wuhu Hospital affiliated to East China Normal University in 2020) (approval number: MER-2019-07-15).

We are grateful to the peer reviewers for their opinions and suggestions.

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Anhui Province (No: 2008085MH245) and the Scientific Research Project of the Second People’s Hospital of Wuhu City (No. 2019B10).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.