1 Department of Obstetrics, Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, 510515 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

2 Department of Obstetrics, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, 510140 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

3 Department of Obstetrics, Dongguan People’s Hospital Affiliated to Southern Medical University and Dongguan Key Laboratory of Major Diseases in Obstetrics and Gynecology, 523058 Dongguan, Guangdong, China

4 Department of Obstetrics, Second Clinical Medical College of Jinan University, 518020 Shenzhen, Guangdong, China

5 Department of Obstetrics, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, 510630 Guangzhou, Guangdong, China

Abstract

Acute pancreatitis in pregnancy (APIP) is a rare but life-threatening complication for both mother and fetus. The purpose of this study was to describe the etiology, clinical indices, early predictive markers and maternal fetal outcomes of APIP.

We retrospectively reviewed 52 APIP cases treated at the 5 tertiary care centers from January 2017 to December 2021 in Guangdong, China. We analyzed the etiology, vital signs, laboratory indices, predictive markers and long-term outcomes of APIP.

The most common causes of APIP were hypertriglyceridemia (36.5%) and biliary disease (26.9%). Heart rate (HR), white blood cell count, the percentage of blood neutrophils, serum glucose and triglycerides were correlated with the severity of APIP. The ability of HR to predict severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) was highest. There were no maternal deaths reported. The overall fetal mortality rate was 7.7% and 62.5% experienced neonatal asphyxia in SAP. Apgar scores among newborns of mild acute pancreatitis (MAP) were not different.

The most frequent cause of APIP has changed and hypertriglyceridemia was the most common cause of APIP. The initial HR recorded after admission might be the new predictor of SAP. The severity of APIP was associated with higher risk of neonatal asphyxia. For MAP patients, conservative treatment was also desirable.

Keywords

- acute pancreatitis in pregnancy

- clinical predictors

- etiology

- long-term prognosis

Acute pancreatitis in pregnancy (APIP) is a life-threatening complication affecting both mother and fetus, with an incidence of approximately 1 in 1000–10,000 pregnancies [1]. Due to its atypical presentations and rapid clinical changes, APIP is easily misdiagnosed and missed by clinicians, resulting in serious adverse maternal and neonatal outcomes. Over the past decades, the APIP-associated mortality rate was high for the mother and fetus, reaching 20% and 50%, respectively [2, 3]. As a consequence of advances in medical knowledge and technology and progress in neonatal intensive care, recent study has reported a decline in maternal and fetal mortality [4].

Until recently, most APIP studies involved small, single-center investigations with a long reference time-period [5, 6]; as such, conclusions may not be generalizable to all patients and all areas. Some larger scale studies have been recently published to describe the clinical features, predictive indicators and pregnancy outcomes of APIP, which provides solid data for further research [7, 8, 9], although some of these studies focused on only one aspect of the disease with the data spanning a period of ten years. In this study, we conducted a retrospective review of 52 cases of APIP treated at 5 tertiary care centers in Guangdong, China, from January 2017 to December 2021. All are specialist centers for critical maternal treatment, and preferentially receive referrals from surrounding hospitals, making them ideal sources for collecting data on APIP patients. Our aim was to describe and update the current data regarding the etiology, clinical features and maternal fetal outcomes of APIP. Additionally, we sought to investigate early predictive markers for severe acute pancreatitis (SAP) and long-term pregnancy outcomes.

This research was conducted as a retrospective, cross-sectional, multicenter study involving patients hospitalized with APIP in Guangdong Province, China: Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University, The Third Affiliated Hospital of Guangzhou Medical University, The First Affiliated Hospital of Jinan University, Dongguan People’s Hospital, and Shenzhen People’s Hospital. Four other hospitals agreed to be involved in study. We utilized data of pregnant patients attending the hospitals from January 2017 to December 2021. The criterion for inclusion was acute pancreatitis diagnosed during pregnancy. Patients meeting the following criteria were excluded: (1) readmission (only included first-time record); (2) pregnancy was terminated prior to admission to hospital; (3) length of more than 7 d from APIP onset to admission; (4) serious comorbidities; and (5) more than 5 missing data of candidate variables.

Data were collected through electronic medical records (EMR); this included maternal age, etiology of acute pancreatitis (AP), disease severity, gestational age at AP onset and delivery, clinical features and complications, diagnostic tests, maternal and fetal outcomes, vital signs, and laboratory test data within 24 h of admission. All data reflected the first inpatient examination following admission.

The classification and diagnostic criteria for APIP were determined according to

the Atlanta Criteria and Clinical practice guidelines [10, 11]. To diagnose acute

pancreatitis, at least 2 of the following 3 criteria must be met: (1) abdominal

pain consistent with acute pancreatitis; (2) serum lipase and/or amylase at least

3 times higher than the upper normal limit; and (3) radiological evidence

indicating acute pancreatitis. Mild acute pancreatitis (MAP) was defined as AP

without organ dysfunction or localized/generalized complications. Moderately

severe acute pancreatitis (MSAP) was defined as AP with transient (within 48 h)

organ dysfunction or localized/generalized complications. Severe acute

pancreatitis (SAP) was defined as AP with persistent (more than 48 h) organ

dysfunction or localized/generalized complications. Organ dysfunction was

assessed based on the modified Marshall score, while local complications

comprised acute peripancreatic fluid collection, pancreatic pseudocyst, acute

necrosis, and walled-off necrosis. By etiology, APIP could be categorized into

acute biliary pancreatitis, hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis (HTGP), or other

types of pancreatitis. Acute biliary pancreatitis was diagnosed by radiological

evidence of abdominal ultrasonography, such as gallstones or sludge in the

biliary tree or the gallbladder [12]. Hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis was

diagnosed with either a serum triglyceride

We conducted all data analyzes using IBM SPSS 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

We excluded variables with

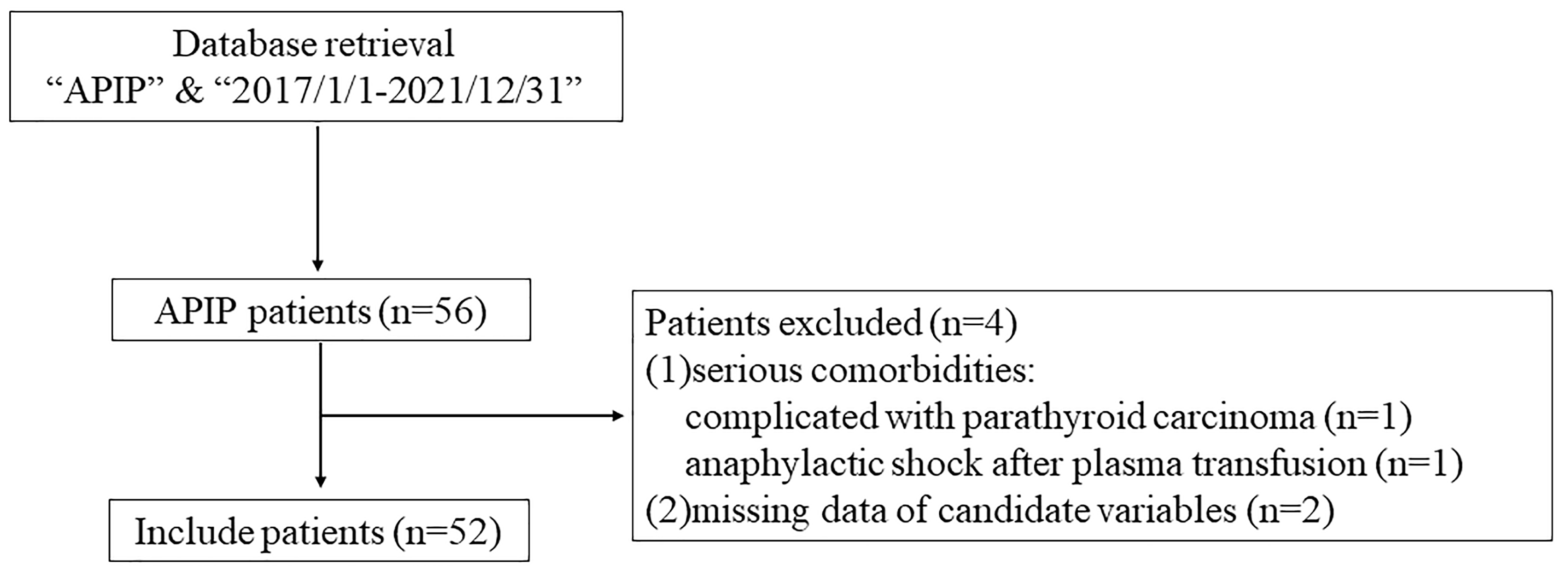

During the study period, a total of 56 APIP patients were reviewed. According to

the inclusion and exclusion criteria, we enrolled 52 pregnant patients in this

study (Fig. 1). The mean maternal age was 30.5

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

The flow chart of the study. APIP, acute pancreatitis in pregnancy.

| MAP | MSAP | SAP | p value | ||

| Individuals (n) | 35 | 9 | 8 | ||

| Age, years | 31.46 |

28.78 |

28.38 |

0.250 | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 26.45 |

27.49 |

28.43 |

0.422 | |

| Gestation weeks on admission (weeks) | 31.71 (7.57) | 36.43 (5.79) | 31.43 (4.14) | 0.056 | |

| Trimester of pregnancy on admission (n) | 0.655 | ||||

| 1st Trimester | 2 | 0 | 0 | ||

| 2nd Trimester | 7 | 0 | 1 | ||

| 3rd Trimester | 26 | 9 | 7 | ||

| Etiology (n) | 0.104 | ||||

| Hyperlipidaemia | 11 | 2 | 6 | ||

| Biliary diseases | 12 | 2 | 0 | ||

| Others | 12 | 5 | 2 | ||

| Inpatient information | |||||

| Hospital stay, days | 10 (7) | 12 (14) | 16.5 (13) | 0.025 | |

| Patients transferred to ICU (n) | 10 | 4 | 7 | 0.008 | |

| Daily hospital charges, RMB (n) | 0.023 | ||||

| 6 | 1 | 1 | |||

| 1000–4999 | 23 | 4 | 1 | ||

| 5000–9999 | 5 | 3 | 4 | ||

| 1 | 1 | 2 | |||

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; ICU, intensive care unit; APIP, acute pancreatitis in pregnancy; MAP, mild acute pancreatitis; MSAP, moderately severe acute pancreatitis; SAP, severe acute pancreatitis. December 31, 2021 exchange rate, 6.378 RMB = 1 US dollar (State Administration of Foreign Exchange, China, 2021).

We compared the clinical data according to the severity of APIP, including baseline clinical data, vital signs, in-hospital information (duration of hospital stay, daily hospitalization charges), and commonly used laboratory indices (Tables 1,2). At baseline, the 3 groups were similar in age, BMI, gestational weeks, and etiology. Hospital length-of-stay and daily charges showed a positive correlation with the severity of APIP. SAP had the highest rate (87.5%) of transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU). Heart rate (HR), white blood cell count (WBC), blood neutrophil percentage (Neu%), serum glucose, and triglycerides were correlated with the severity of APIP.

| MAP (n = 35) | MSAP (n = 9) | SAP (n = 8) | p value | ||

| Vital signs | |||||

| SBP, mmHg | 112 (11) | 118 (17) | 137 (37) | 0.115 | |

| DBP, mmHg | 74 (9) | 73 (14) | 69 (23) | 0.958 | |

| Temp, °C | 36.7 (0.4) | 36.5 (0.5) | 36.6 (0.7) | 0.825 | |

| HR, bpm | 93 |

92 |

121 |

||

| Laboratory test data | |||||

| WBC, |

11.20 |

10.26 |

17.16 |

0.011 | |

| Neu% | 79.9 |

74.2 |

89.9 |

0.024 | |

| HCT, L/L | 0.32 |

0.33 |

0.30 |

0.107 | |

| CRP, mg/L | 30.0 (49.1) | 39.1 (152.3) | 123.4 (199.9) | 0.100 | |

| K, mmol/L | 3.77 |

3.67 |

3.76 |

0.799 | |

| Ca, mmol/L | 2.12 |

2.15 |

2.07 |

0.556 | |

| Glu, mmol/L | 5.70 (2.83) | 5.40 (2.43) | 8.70 (5.26) | 0.016 | |

| Amylase, U/L | 161.1 (218.8) | 122.0 (544.9) | 89.8 (382.0) | 0.577 | |

| ALT, U/L | 14.9 (16.8) | 7.3 (9.7) | 9.6 (7.8) | 0.220 | |

| AST, U/L | 19.4 (17.5) | 19.9 (16.1) | 21.5 (13.5) | 0.993 | |

| ALB, g/L | 31.7 |

32.7 |

30.2 |

0.433 | |

| TBil, µmol/L | 10.81 (9.70) | 9.66 (11.10) | 7.86 (10.70) | 0.648 | |

| DBil, µmol/L | 3.85 (6.08) | 5.37 (6.10) | 4.99 (6.64) | 0.515 | |

| Cr, µmol/L | 44.4 |

46.9 |

36.2 |

0.261 | |

| TG, mmol/L | 2.33 (4.80) | 3.07 (3.30) | 15.48 (41.12) | 0.016 | |

| TC, mmol/L | 5.70 (4.09) | 6.19 (4.94) | 11.57 (20.07) | 0.087 | |

Abbreviations: SBP, systolic pressure; DBP, diastolic pressure; HR, heart rate; WBC, white blood cell count; Neu%, blood neutrophil percentage; HCT, hematocrit; CRP, C-reactive protein; K, serum potassium; Ca, total calcium; Glu, serum glucose; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; ALB, seralbumin; TBil, total bilirubin; DBil, direct bilirubin; Cr, creatinine; TG, triglycerides; TC, total cholesterol.

We found that some clinical indicators were significantly different between the

3 groups (Table 2), so we constructed receiver operating characteristic (ROC)

curves to compare the values of the indicators to predict SAP and identify

cut-off values (Fig. 2). The area under the curve (AUC) and the optimal cut-off

values are summarized in Table 3. HR had the greatest ability to predict SAP (AUC

= 0.950, p

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of clinical indicators for predicting SAP. SAP, severe acute pancreatitis; WBC, blood cell count; Neu%, blood neutrophil percentage; TG, triglycerides; HR, heart rate

| Variables | AUC | 95% CI | p value | Cut-off | Sensitivity | Specificity |

| WBC | 0.813 | 0.646–0.979 | 0.005 | 12.65 | 0.875 | 0.750 |

| Neu% | 0.824 | 0.705–0.943 | 0.004 | 87.65 | 0.875 | 0.723 |

| Glucose | 0.820 | 0.657–0.983 | 0.004 | 6.395 | 0.875 | 0.705 |

| TG | 0.827 | 0.707–0.946 | 0.004 | 3.88 | 1.000 | 0.614 |

| HR | 0.950 | 0.882–1.000 | 112 | 0.875 | 0.932 |

Abbreviations: AUC, area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

| Variables | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | ||||

| Coefficient | p value | OR (95% CI) | Coefficient | p value | OR (95% CI) | |

| WBC | 0.192 | 0.010 | 1.212(1.047–1.403) | –0.114 | 0.495 | 0.892 (0.644–1.237) |

| Neu% | 0.201 | 0.041 | 1.222 (1.008–1.481) | 0.396 | 0.254 | 1.486 (0.752–2.934) |

| Glucose | 0.426 | 0.010 | 1.531 (1.109–2.114) | 0.264 | 0.556 | 1.303 (0.541–3.138) |

| TG | 0.038 | 0.030 | 1.039 (1.004–1.075) | 0.036 | 0.441 | 1.037 (0.946–1.137) |

| HR | 0.202 | 0.004 | 1.224 (1.068–1.402) | 0.242 | 0.030 | 1.274 (1.024–1.585) |

Abbreviations: OR, odds ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

As shown in Table 5, the overall fetal mortality rate was 7.7% (4/52). Four fetal losses were all in MAP; 3 involved induced abortion due to concerns about the disease or medications affecting pregnancy and 1 experienced an intrauterine demise of unknown origin (the woman only accepted the test for therapeutic purposes). Early and moderately preterm births occurred in 26.9% (14/52) and 1.9% (1/52) were extremely preterm births (at 27.9 weeks). Of all live births, 7 newborns were diagnosed with neonatal asphyxia. Thirteen patients with MAP were able to continue with their pregnancy on discharge. Further-more, we followed up 6 long-term outcomes of the 13 patients from their EMR. The median gestational age of these 6 women was 39.7 (7.7) weeks. We defined the newborns in MAP who were delivered during admission due to APIP as group A, and the 6 newborns in a continuing pregnancy as group B. There was no statistical difference in Apgar scores between the two newborn groups (Table 6).

| Total number, n (%) | MAP (n = 35) | MSAP (n = 9) | SAP (n = 8) |

| Continued pregnancy | 13 (37.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Total life birth | 18 (51.4%) | 9 (100.0%) | 8 (100.0%) |

| Cesarean birth | 15 (42.9%) | 9 (100.0%) | 8 (100.0%) |

| Vaginal birth | 3 (8.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Early and moderately preterm birth | 6 (17.1%) | 3 (33.3%) | 5 (62.5%) |

| Extremely preterm birth | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (12.5%) |

| Total fetal loss | 4 (11.5%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Spontaneous abortion | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Artificial abortion | 3 (8.6%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Intrauterine fetal death | 1 (2.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Stillbirth | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Neonatal asphyxia | 1 (2.9%) | 1 (11.1%) | 5 (62.5%) |

| Number | Apgar | |||

| 1 min | 5 min | 10 min | ||

| Group A | 18 | 10 (2.0) | 10 (0.0) | 10 (0.0) |

| Group B | 6 | 9 (0.0) | 9 (1.0) | 10 (0.0) |

| p value | - | 0.454 | 0.177 | 0.871 |

Group A: the newborns in MAP who were delivered during admission due to APIP; Group B: the 6 newborns in a continuing pregnancy.

APIP is a rare type of acute pancreatitis and remains a challenging clinical problem. Maternal physiological changes that occur during pregnancy make the condition more complicated. In our retrospective study, we analyzed 52 APIP cases from Guangdong Province, China admitted from 2017 to 2021. We aimed to provide an update of clinical disease features and to identify the best predictors for the severity of APIP. The majority of APIP (81.25%) occurred in the third trimester, which is also consistent with previous studies [7, 13]. In addition, the incidence of MSAP and SAP increased during the third trimester, indicating that the incidence and severity of APIP increased as the pregnancy progressed.

In our study, the most frequent cause of APIP was hyperlipidaemia, followed by biliary disease. During normal pregnancy, multiple changes in the levels of hormones during pregnancy cause adaptive changes in carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. In women with an altered lipoprotein metabolism, these changes cause marked hypertriglyceridemia [1, 14]. Additionally, in the context of hyperlipidemia, a physiologic hypercoagulable state during pregnancy and fat emboli in the pancreatic vessels may combine to impair pancreatic microcirculation, in turn leading to pancreatic damage and acute pancreatitis [15]. However, in China, hyperlipidemia is not the leading cause of APIP. According to the findings of a previous meta-analysis conducted by investigators from our hospital [16], the most common cause of APIP was biliary disease. This changed after 2009, with more pregnancy-associated hypertriglyceridemic pancreatitis being reported and hyperlipidaemia has become the main trigger of APIP, with a rate of 37%. These changes may stem from the rapid growth of the Chinese economy, improved living standards, and changes in diet during pregnancy. Marked changes in the etiology of APIP have also been reported in studies from different regions around the world [4, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25] (Table 7, Ref. [4, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25]), suggesting that ethnic or environmental factors might affect the pathogenesis of APIP. It is commonly accepted that biliary disease is the most common etiology for APIP in Europe, North America, and India [24, 26, 27]. During pregnancy, elevated progesterone levels can alter gallbladder motility, leading to bile stasis. Additionally, high estrogen levels can modify the composition of bile, making it more lithogenic. These changes may increase the risk of developing AP [22, 28]. However, hyperlipidemia is the major causal factor in East Asian countries such as China and South Korea. One reason for this phenomenon may stem from a lower prevalence of gallstones in Asian countries compared to western countries [24, 27]. In addition, there are recognized ethnic differences in the levels of baseline triglycerides; these are highest in East Asians, followed by Caucasians, and lowest in South Asians and African Americans [29]. However, we also observed from Table 7 that APIP etiologies differ between countries and regions on the same continent, even in the context of similar geographical and racial factors. As such, lifestyle factors such as diet may play a critical role in the pathogenesis of APIP.

| Area | Etiologies | ||

| Biliary disease (%) | Hyperlipidemia (%) | ||

| Asia | China [16] | 33.00 | 37.00 |

| India [17, 18, 19] | 53.80 | 19.20 | |

| South Korea [25] | 0.00 | 100.00 | |

| America | The United State [4] | 88.00 | 0.00 |

| Canada [20] | 65.80 | 0.91 | |

| French Guiana [21] | 40.00 | -1 | |

| Europe | Italy [22] | 38.20 | -2 |

| Spain [23] | 84.20 | 5.30 | |

| Turkey [24] | 54.50 | 33.30 | |

1missing data, blood lipid profiles were not examined in study. 2missing data, only acute biliary pancreatitis was provided in study.

As demonstrated in our study, SAP mostly occurred during the second and third trimesters and was associated with a high proportion of adverse maternal-fetal outcomes. Other studies also support the link between APIP severity and higher risks of poor maternal and fetal outcomes [5, 7, 30]. Approximately 5–10% of acute pancreatitis patients will develop severe acute pancreatitis in the general population in China [11], while there was 15.4% SAP in pregnant patients in our study. We also found a significant positive correlation between disease severity, daily healthcare costs and the duration of stay in the hospital. SAP showed the highest rate of transfer to the ICU. Thus, SAP imparted significant financial strains on the family and increased healthcare burdens on an already stressed health system. We suggest the following possible reasons for the adverse effects of SAP. There is an inevitable delay in diagnosis, particularly in patients with SAP compared with those with MAP [30]. The most common initial symptoms of APIP, such as epigastric pain, nausea, and vomiting during mid to late gestation are likely to be ascribed to the pregnancy, leading to misdiagnoses and delayed treatments [5, 31]. SAP requires significant medical resources, thus incurring high treatment costs; these are likely to be higher if multiple rounds of testing are required and treatment is delayed. Thus, early recognition and prompt treatment of APIP are vitally important.

The majority of previous retrospective studies only summarized and reported the

clinical features of APIP [5, 7, 32]. In addition, most studies into the early

predictors of SAP have focused only on acute pancreatitis in the non-pregnant

population, such as the association of neutrophil–lymphocyte ratio (NLR), red

cell distribution width (RDW), and C-reactive protein (CRP) with AP [33, 34].

Only a few studies have collected routine laboratory tests after APIP onset to

evaluate the predictive values of these tests on APIP severity [9, 15]. From that

study, lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and RDW was able to predict SAP early, and low

serum triglycerides (

The complexities of managing APIP arise from the decision-making involved in the

timing and route of pregnancy termination. There are currently no standardized

guidelines to instruct the diagnosis and treatment of APIP. Luo et al.

[7] provided some recommendations for indicators for the termination of

pregnancy: (1) when organ dysfunction exists, continuing pregnancy might

aggravate the disease; (2) during the first two trimesters of pregnancy, clinical

medications might affect the growth of the fetus; (3) fetal development is

basically mature (after 37 weeks), systemic inflammation response syndrome (SIRS)

caused by APIP and clinical medications might increase the risk of fetal death

[7]. At our medical center, a multidisciplinary team, including obstetrics,

hepatobiliary surgery, gastroenterology and ICU, would be constructed to assess

the medical condition of APIP and decide whether to terminate pregnancy.

Consistent with the conclusion of other studies [5, 13], in this study, adverse

outcomes occurred more frequently among pregnant patients diagnosed with MSAP and

SAP, compared to MAP. Therefore, early diagnosis and timely treatment for MSAP

and SAP should confer marked benefits. Conservative management is suggested for

patients with MAP [40], implying that continuation of pregnancy for MAP after

conservative treatment would be safe. Though multidisciplinary consultation has

done to assess medical condition and provide personalized treatment options, some

pregnant women will still request induction out of concerns about their medical

condition and fetal toxicity arising from the drug treatments. Long-term outcomes

for continued pregnancy in MAP have not been previously reported. In this study,

we recorded outcomes from 6 long-term cases of continued pregnancy in MAP and the

HRs of these 6 pregnant patients were all

This study has some limitations. Firstly, a retrospective study has inherent limitations. We could investigate associations but could not infer causation. Secondly, there is no available guideline to provide standard management of APIP. Guideline of acute pancreatitis was used to identify APIP, which might limit the generalization of the results. In addition, this study consisted of a small sample size. Due to the low incidence of APIP, to recruit a large number of study patients is quite difficult. Besides, the recruitment of patients from tertiary hospitals might lead to selection bias. However, this is currently the largest cohort in order to investigate APIP in Guangdong Province.

APIP is a rare but severe disease that potentially threatens maternal and fetal wellbeing. Hypertriglyceridemia was the most common etiology of APIP, suggesting that a greater focus should be given to nutrition and metabolic health in pregnant patients. The severity of APIP was correlated with a higher risk of poor outcomes, suggesting that a specific and sensitive marker to predict SAP is required. HR recorded after admission may be a predictor of APIP. For APIP patients, it is important to consider the most appropriate timing for pregnancy termination, but for MAP patients, conservative treatment is a likely option. More research is required to elucidate the etiology, clinical predictors, and treatments of APIP.

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

JL, JJ and FH conceived and designed the project. JL, RL, ZL, YY and DQ collected the data. JL and RL analyzed and interpreted the data. JL drafted the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University (approval No. NFEC-2022-247). The records and data did not include identifying patient information and the analysis was based on retrospective record review, so individual informed consent was not required. The informed consent has been exempted by the Institutional Review Board of the Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University.

We are grateful to the hospital collaborators for assistance in data collection.

This study was supported by Clinical Research Fundation of Nanfang Hospital, Southern Medical University (2019CR014).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.