1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University Hospital Puerto Real (Cádiz), 11510 Puerto Real, Cádiz, Spain

2 Institute of Research and Innovation in Biomedical Sciences of the Province of Cadiz (INiBICA), Hospital Universitario Puerta del Mar, 11009 Cádiz, Spain

†These authors contributed equally.

Abstract

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the third most prevalent neoplasm among women in Spain and the most frequent malignancy of the female genital tract. The primary risk factors are associated with increased estrogen levels. The objective of our study is to determine the current specific progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) in patients with EC at the University Hospital of Puerto Real. Additionally, we aim to understand the independent role of specific factors in the risk of recurrence and mortality from EC through a multivariate analysis.

A retrospective observational survival analysis of a case series was conducted. The study population included all women diagnosed and treated for EC in Spain between January 2010 and December 2021. The Kaplan-Meier method and Cox regression analysis were performed to evaluate survival based on patient age, tumor stage, histological type, and degree of differentiation, and to quantify survival probabilities for each factor.

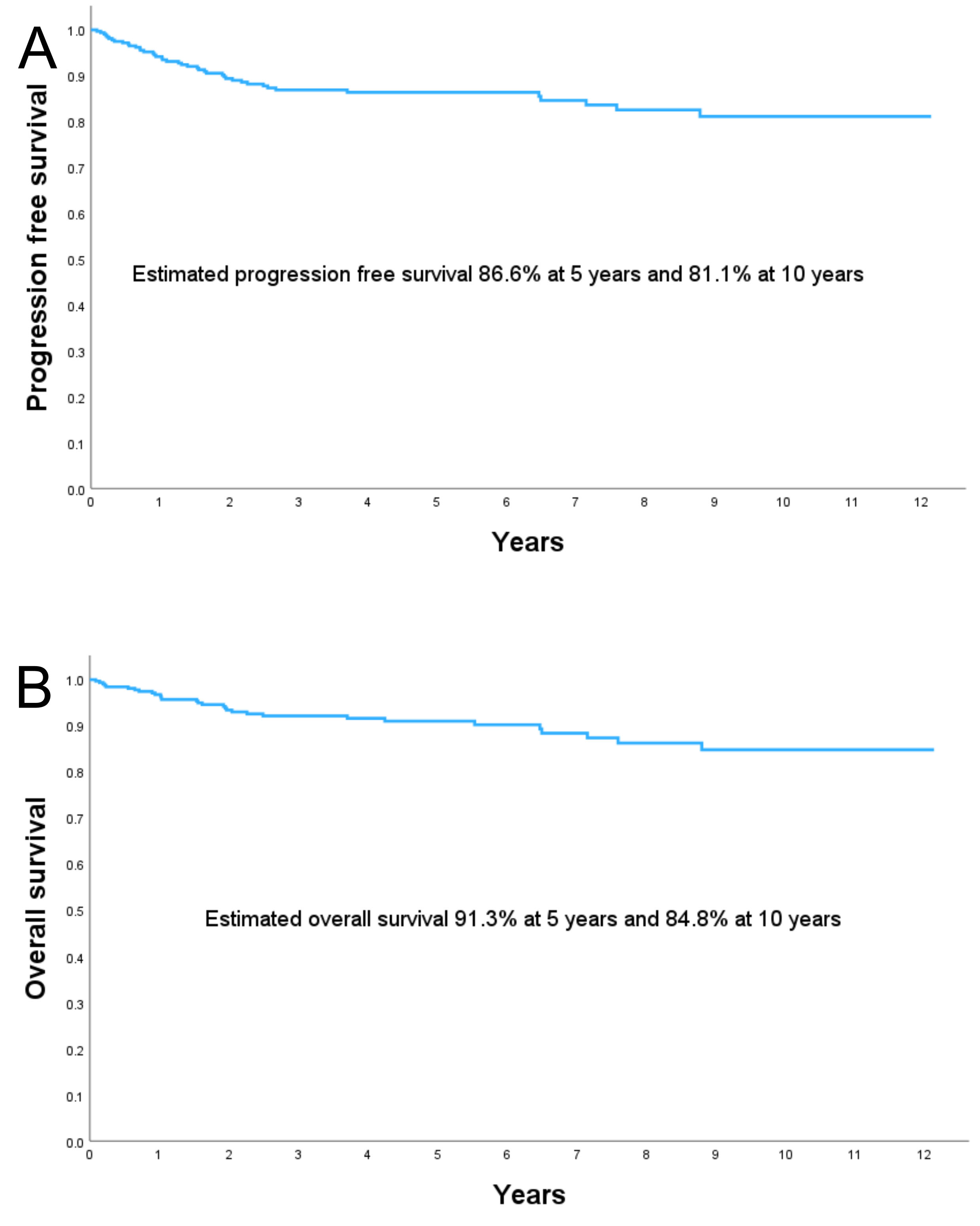

A total of 324 patients were included. The PFS was 86.6% at 5 years and 81.1% at 10 years. The OS was 91.3% at 5 years and 84.8% at 10 years. The tumor-related mortality rate was 9.3% (N = 30) and the tumor recurrence rate was 5.6% (N = 18). The estimated median follow-up using the inverse Kaplan-Meier method was 4.33 years (95% confidence interval (95% CI): 3.72–4.94) for OS and 4.57 years (95% CI: 4.05–5.09) for PFS. The statistically significant factors affecting PFS and OS were age ≥60 years at diagnosis, advanced International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage (II–IV), non-endometrioid tumor, high tumor grade, and lymphovascular space invasion. Multivariate Cox regression analysis shows that being 60 years or older at the time of diagnosis, advanced FIGO stages, high tumor grade, and serous-papillary tumors are independent risk factors for recurrence or death in EC.

Our study shows that being 60 years or older at the time of diagnosis, advanced FIGO stages (II–IV), non-endometrioid EC, higher histological tumor grade, and lymphovascular space invasion are associated with lower OS and PFS. Additionally, multivariate Cox analysis suggests that age ≥60 years at diagnosis, advanced FIGO stages, high tumor grade, and serous-papillary histological type are independent prognostic factors influencing survival and recurrence in EC. This study should serve as a foundation for further research, incorporating relevant aspects of the molecular biology of EC to refine patient prognosis.

Keywords

- endometrial cancer

- gynecologic oncology

- progression-free survival

- overall survival

In Spain, endometrial cancer (EC) is the third most prevalent carcinoma among women and the most common malignancy of the female genital tract. In Europe, it ranks as the eighth most common cause of cancer-related death among women [1]. The incidence of EC has been increasing over the past few decades, primarily due to rising obesity rates and increased life expectancy [2]. EC can be classified into two types based on estrogen dependence. Type I, known as endometrioid cancer, accounts for 80% of EC cases. In contrast, Type II is not associated with estrogen exposure and generally has a worse prognosis [3]. Histological differentiation of endometrial tumors is based on the percentage of non-squamous solid growth. Tumors with less than 5% solid component are classified as low-grade (G1), those with 6–50% solid component as moderate-grade (G2), and those with over 50% solid component as high-grade (G3) [4, 5]. Staging is performed according to the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) system [6] and the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) tumor node metastases (TNM) classification [7], considering local tumor extension and distant metastasis.

Risk factors for EC are associated with conditions that lead to elevated estrogen levels. Obesity, a sedentary lifestyle, hypertension, and diabetes (all endogenous factors promoting hyperestrogenism) are known to increase the risk of developing this condition. Additionally, exogenous factors, such as unopposed estrogen replacement therapy, also contribute to the risk. Hereditary risk factors unrelated to hormones, such as Lynch syndrome, are also relevant [8, 9]. Prognostic factors for EC include tumor stage [10, 11], histological type [12], histological grade [13], myometrial invasion [14], lymphovascular space invasion [15], tumor size, and molecular classification [16, 17]. Additional prognostic factors include age over 60 years, positive peritoneal cytology [18], adnexal involvement, and lymph node metastasis [19].

In recent years, there have been significant advancements in the management of EC. Clinical trial results have demonstrated that immunotherapy, specifically immune checkpoint inhibitors such as pembrolizumab and dostarlimab, improves progression-free survival (PFS) in patients with advanced EC [20, 21]. Another important advancement is sentinel lymph node mapping, which limits the extent of surgical intervention and improves the identification of affected lymph nodes [22]. Finally, the adoption of molecular and genomic profiling has enhanced the understanding of tumor biology and facilitated the personalization of treatment [23, 24].

A recent article published by Adekanmbi et al. [25] analyzes overall survival (OS) in patients with EC in the United States from 2005 to 2020. The authors demonstrate a progressive increase in 5-year OS in patients with EC, with rates of 78.4% for 2005–2008, 79.7% for 2009–2012, and 80.8% for 2013–2016 [25].

In Europe, Steiner et al. [26] reported a 5-year OS rate of 78.4% for EC in a population of German women during the period from 1985 to 1995. However, more recently, Coronado et al. [27], conducted a retrospective study of women diagnosed with EC between 2005 and 2018, and they reported a 5-year OS rate of 91.4% in the minimally invasive surgery group (robotic or laparoscopic) and 89.9% in the open surgery group, considering only deaths directly related to EC.

The objective of our study is to determine the current PFS and OS in patients with EC in our setting. Additionally, we aim to analyze the independent roles that various factors in the risk of recurrence and mortality from EC through multivariate analysis.

This retrospective observational study analyzed survival outcomes in a series of EC cases.

The study population consisted of consecutive women who were histologically diagnosed and treated for EC at the University Hospital of Puerto Real in Cádiz, Spain, between January 2010 and December 2021. The only inclusion criterion considered in the study was a confirmed histological diagnosis of EC. Patients who received treatment at another center were excluded from the study. The final study cohort comprised 324 patients.

Clinical data necessary for the study were retrieved from the hospital’s information system. The study variables included tumor stage, histological type and grade, presence of lymph node metastasis, age, and associated comorbidities (such as obesity, hypertension, and type 2 diabetes). Additionally, data on the treatment received by the patients, including surgical, hormone therapy, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, were collected. The dependent variables were time to death from EC and time to recurrence from the start of treatment. The study received ethical approval from the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Cádiz on March 4, 2022, with ethic approval number 0177-N-22.

Until 2018, the standard surgical treatment for low- and intermediate-risk patients was extrafascial total hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy and pelvic lymphadenectomy. However, since 2018, lymphadenectomy has been avoided in low-risk patients — those with low-grade (G1-G2) endometrioid cancer and less than 50% myometrial invasion as determined by ultrasound or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). For high-risk patients or those with aggressive histological types (such as serous, endometrioid G3, or clear cell carcinoma), para-aortic lymphadenectomy was performed at the surgeon’s discretion following pelvic lymphadenectomy. Infracolic omentectomy was conducted in cases of serous carcinoma. Staging was performed according to the FIGO 2009 classification.

Surgeries from 2010 to 2018 were performed via laparotomy. From February 2018 to 2021, surgeries were conducted using a laparoscopic approach.

Adjuvant treatment decisions were made by a multidisciplinary tumor board, in accordance with the recommendations of the Spanish guidelines [28, 29]. Follow-up protocols varied according to risk groups. Low- and intermediate-risk patients were scheduled for clinical examinations and ultrasounds every six months for the first two years after surgery, and then annually until the fifth year. High-intermediate and high-risk patients were scheduled for visits every four months, including clinical examinations and imaging studies (computed tomography (CT) scan or ultrasound) as needed based on symptoms, for the first two years post-surgery, and then every six months until the fifth year. All patients who received chemotherapy were followed by the Medical Oncology department with CT scans and blood tests every four months during the first two years, and annually thereafter until recurrence or for up to five years.

A descriptive analysis of the variables was performed. The normality of quantitative variables was assessed using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Since none of the variables followed a normal distribution, they were described using the median as the measure of central tendency and the interquartile range (IQR) as the measure of dispersion. Qualitative variables were described in terms of frequencies and percentages.

OS and PFS were calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and differences between

curves were evaluated by log-rank test. Survival time was computed from the start

of treatment until the occurrence of the event studied (recurrence or death). For

the survival analysis, only cases in which death was related to EC were included.

Cases where the cause of death was not related to EC were considered censored.

Furthermore, in order to evaluate the role that each variable studied plays in

the prognosis of EC, we performed a multivariate analysis using the Cox

regression model. The risk of recurrence and death was expressed as a hazard

ratio (HR) with a 95% confidence interval (95% CI). A p-value of

A total of 325 patients were initially included in our study. However, 1 patient decided to receive treatment at another center, leaving 324 patients in the final analysis. The median age at diagnosis was 64.47 years (IQR: 16.43 years). Notably, 63.9% of these patients were over 60 years old. The median body mass index (BMI) was 30.84 kg/m2 (IQR: 9.06 kg/m2). Among the patients, 86.4% were postmenopausal, 57.1% had hypertension, and 25.9% had type 2 diabetes.

The most frequent histological type was endometrioid (76.2%), followed by serous-papillary tumor (9.6%). Regarding histological grade, most cases included in the study showed moderate differentiation (G2) at 42.0%, followed by low grade (G1) at 40.2%, and high grade (G3) at 17.8%. At diagnosis, 81.0% of patients were classified as stage I, with 61.4% in stage IA and 19.6% in stage IB. Additionally, 4.6% of patients had pelvic lymph node metastasis, while 1.5% had para-aortic lymph node metastasis (Table 1).

| Variable | (n) | (%) | ||

| Age at diagnosis | ||||

| 117 | 36.1 | |||

| 207 | 63.9 | |||

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Underweight | 1 | 0.3 | ||

| Normal | 38 | 11.7 | ||

| Overweight | 127 | 39.2 | ||

| Obesity | ||||

| Type I | 73 | 22.5 | ||

| Type II | 56 | 17.3 | ||

| Type III | 29 | 9.0 | ||

| Menopause | ||||

| No | 44 | 13.6 | ||

| Yes | 280 | 86.4 | ||

| Type 2 diabetes | ||||

| No | 240 | 74.1 | ||

| Yes | 84 | 25.9 | ||

| Hypertension | ||||

| No | 139 | 42.9 | ||

| Yes | 185 | 57.1 | ||

| Histological grade | ||||

| G1 | 130 | 40.2 | ||

| G2 | 137 | 42.0 | ||

| G3 | 50 | 17.8 | ||

| Histological type | ||||

| Endometrioid | 247 | 76.2 | ||

| Serous-papillary | 31 | 9.6 | ||

| Others | 46 | 14.2 | ||

| Tumoral stage | ||||

| I-A | 194 | 61.4 | ||

| I-B | 64 | 19.6 | ||

| II | 17 | 5.4 | ||

| III-A | 10 | 3.2 | ||

| III-B | 5 | 1.6 | ||

| III-C1 | 12 | 3.8 | ||

| III-C2 | 5 | 1.6 | ||

| IV-A | 3 | 0.9 | ||

| IV-B | 8 | 2.5 | ||

| Lymph node metastasis | ||||

| Pelvic | 15 | 4.6 | ||

| Para-aortic | 5 | 1.5 | ||

BMI, body mass index.

Of the 324 patients included in the study, 307 (94.8%) underwent surgical treatment. Surgical treatment was not performed for 17 patients due to inoperable tumors. Of these 17 patients, 1 was treated with hormone therapy, 1 received radiotherapy, 2 received both radiotherapy and brachytherapy, and the remaining patients received palliative care.

Of the 307 patients who underwent surgery, 4 (1.3%) died due to surgical complications. Table 2 shows the therapeutic regimens followed by the remaining 303 patients. Of these, 157 patients (51.82%) did not require adjuvant treatment, 1 patient received treatment with progestins, 14 patients (4.62%) received chemotherapy alone, and the remaining patients (N = 131, 42.7%) underwent various radiotherapy regimens.

| Adjuvant treatment | Patients, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Follow-up | 157 (51.82) |

| Hormone therapy | 1 (0.33) |

| Brachytherapy | 57 (18.81) |

| Radiotherapy + Brachytherapy | 49 (16.17) |

| Radiotherapy + Chemotherapy | 25 (8.25) |

| Chemotherapy | 14 (4.62) |

The PFS rate was 86.6% at 5 years and 81.1% at 10 years. The OS rate was 91.3% at 5 years and 84.8% at 10 years (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

(A) PFS, and (B) OS in the study population. PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival.

The tumor-related mortality rate was 9.3% (N = 30) and the tumor recurrence rate was 5.6% (N = 18). The estimated median follow-up, using the inverse Kaplan-Meier method, was 4.33 years (95% CI: 3.72–4.94) for OS and 4.57 years (95% CI: 4.05–5.09) for PFS.

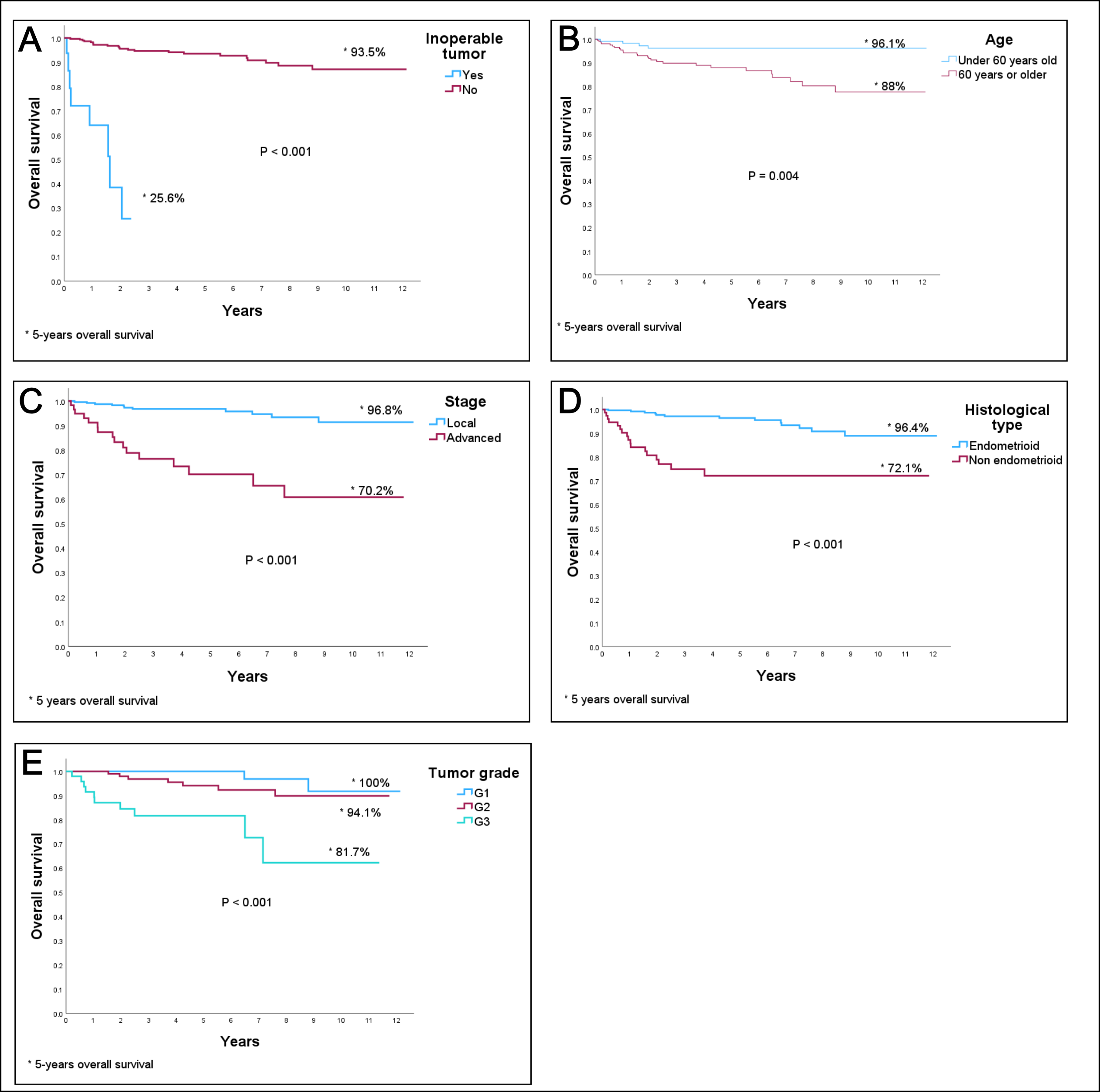

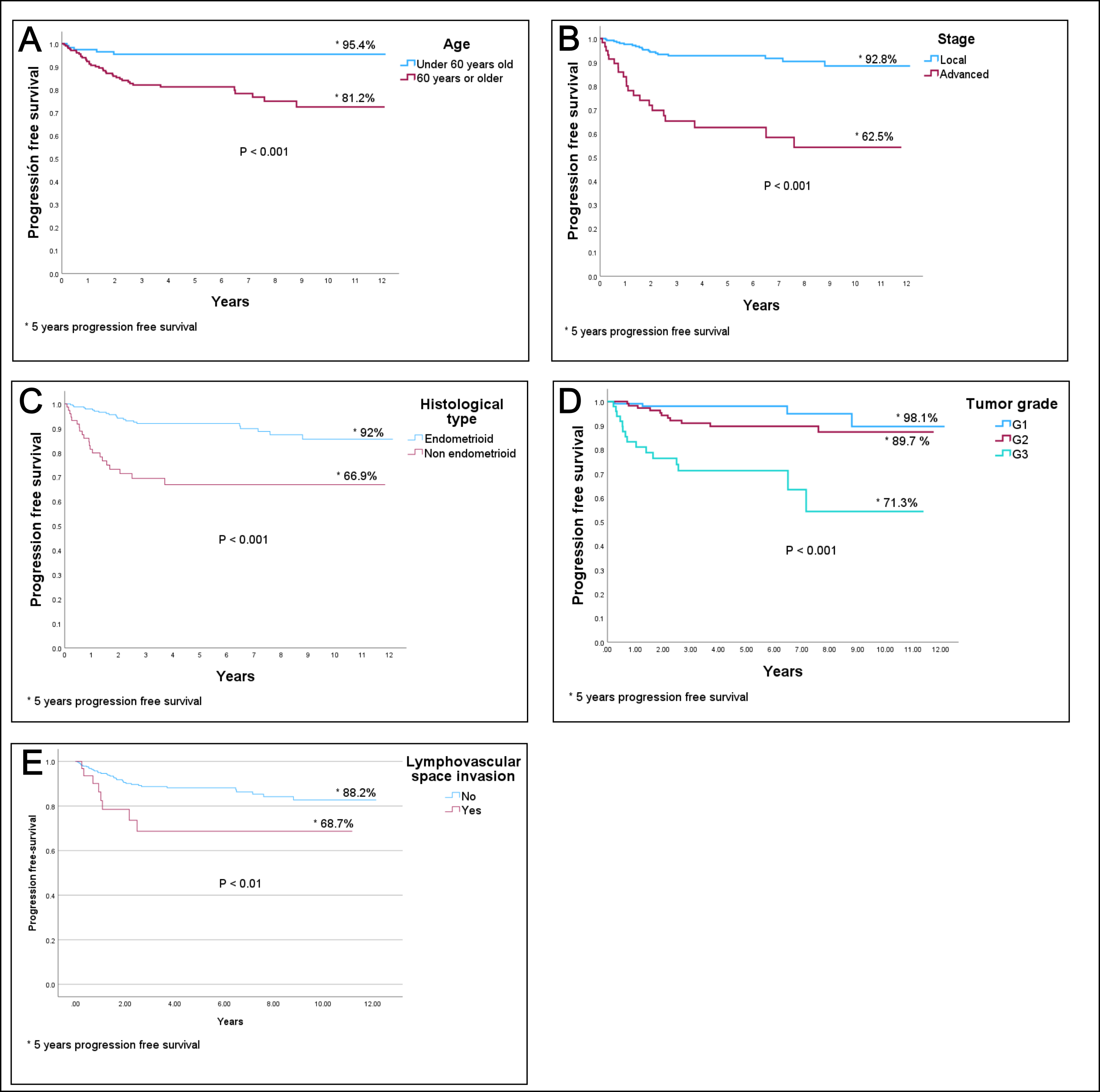

Table 3 shows the results of the PFS and OS analysis according to the Kaplan-Meier method. As expected, patients who were unable to undergo surgical treatment exhibited high mortality, with a 5-year survival rate of only 25.6%. Other factors associated with decreased PFS include age 60 years or older at diagnosis, advanced FIGO stage, non-endometrioid tumor type, tumor grade, and lymphovascular invasion. Regarding the surgical approach, patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery exhibited better survival rates (both OS and PFS) compared to those who had laparotomy. However, as detailed in the Materials and Methods section, a potential temporal bias must be considered, as patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery were operated on in the later years of the study period.

| PFS | OS | ||||

| Percentage | p-value* | Percentage | p-value* | ||

| Inoperable tumor | |||||

| No | - | - | 93.5 | - | |

| Yes | - | - | 25.6 | ||

| Age (years) | |||||

| 95.4 | - | 96.1 | - | ||

| 81.2 | 88.0 | 0.004 | |||

| FIGO stage | |||||

| Local (stage I) | 92.8 | - | 96.8 | - | |

| Advanced (stages II–IV) | 62.5 | 70.2 | |||

| Histological type | |||||

| Endometrioid | 92.0 | - | 96.4 | - | |

| Non-endometrioid | 66.9 | 72.1 | |||

| Tumor grade | |||||

| G1 | 98.1 | - | 100.0 | - | |

| G2 | 89.7 | 94.1 | |||

| G3 | 71.3 | 81.7 | |||

| Lymphovascular space invasion | |||||

| Negative | 88.2 | - | 91.8 | - | |

| Positive | 68.7 | 0.005 | 83.0 | 0.007 | |

| Surgical approach | |||||

| Laparoscopy | 95.0 | - | 99.0 | - | |

| Laparotomy | 86.3 | 90.1 | 0.007 | ||

| Pelvic lymphadenectomy | |||||

| No | 89.0 | - | 94.4 | - | |

| Yes | 89.1 | 0.155 | 92.8 | 0.278 | |

| Para-aortic lymphadenectomy | |||||

| No | 89.2 | - | 93.6 | - | |

| Yes | 87.2 | 0.071 | 92.5 | 0.621 | |

* Log-rank test. PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.

We did not find statistically significant relation between performing pelvic and/or para-aortic lymphadenectomy and either OS or PFS.

Figs. 2,3 display the most relevant survival curves obtained from the previous analysis. The most relevant prognostic factors related to survival are shown in Fig. 2 (OS) and Fig. 3 (PFS).

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

OS curves by (A) inoperable tumor, (B) age, (C) FIGO stage, (D) histological type, and (E) tumor grade. OS, overall survival; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. * 5 years overall survival.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

PFS curves by (A) age, (B) FIGO stage, (C) histological type, (D) tumor grade, and (E) lymphovascular space invasion. PFS, progression-free survival; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics.* 5 years progression free survival.

In Table 4, we show the results of the multivariate Cox regression analysis. The factor with the greatest impact on both PFS and OS was being 60 years or older at diagnosis (HR for PFS: 7.59 [95% CI: 1.78–32.28]; HR for OS: 9.47 [95% CI: 1.25–71.74]). Other factors that significantly increased the risk of recurrence or death from EC include advanced FIGO stage, high tumor grade, and serous-papillary tumor type.

| Variables | PFS | OS | |||||||||

| B | SE | Wald | HR (95% CI) | p-value | B | SE | Wald | HR (95% CI) | p-value | ||

| Age |

2.04 | 0.74 | 7.54 | 7.59 (1.78–32.28) | 0.006 | 2.25 | 1.03 | 4.73 | 9.47 (1.25–71.74) | 0.03 | |

| Advanced stage (II–IV) | 1.13 | 0.40 | 8.01 | 3.09 (1.47–6.75) | 0.005 | 1.11 | 0.50 | 4.96 | 3.04 (1.14–8.08) | 0.026 | |

| Tumor grade | |||||||||||

| G2 | 0.58 | 0.59 | 0.96 | 1.78 (0.56–5.68) | 0.327 | 0.70 | 0.81 | 0.76 | 2.02 (0.41–9.89) | 0.385 | |

| G3 | 1.81 | 0.62 | 8.66 | 6.13 (1.83–20.52) | 0.003 | 1.84 | 0.85 | 4.62 | 6.28 (1.18–33.55) | 0.032 | |

| Serous-papillary | 0.32 | 0.52 | 0.38 | 1.38 (0.50–3.85) | 0.535 | 1.45 | 0.67 | 4.71 | 4.27 (1.15–15.83) | 0.03 | |

PFS, progression-free survival; OS, overall survival; B, beta coefficient; SE, standard error; HR, hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval.

In our sample of 324 patients with EC, the PFS was 86.6% at 5 years and 81.1% at 10 years. Similarly, the OS was 91.3% at 5 years and 84.8% at 10 years. Patients with inoperable tumors at the time of diagnosis had a poor prognosis, with a 5-year survival rate of 25.6%. Other factors associated with lower PFS and OS rates included being 60 years or older at the time of diagnosis, advanced FIGO stages (II–IV), non-endometrioid EC, higher tumor histological grade (G2 and G3 vs. G1), and lymphovascular space invasion.

Multivariate Cox regression analysis revealed that, for the same FIGO stage, histological type, and tumor grade, the factor most significantly increasing the risk of recurrence or death was being 60 years or older at diagnosis. Additionally, the Cox analysis revealed that women with a G3 tumor had approximately six times the risk of recurrence or death compared to those with a G1 tumor. Taken together, patients diagnosed at FIGO stages II to IV had approximately three times the risk of recurrence or death compared to those diagnosed at FIGO stage I. Finally, the multivariate analysis showed that patients with serous-papillary histological type tumors had four times the risk of death compared to those with endometrioid EC.

Our population appears to be very similar to those previously described in the literature. The median age of the patients included in our study was similar to that reported by Rouzier and Legoff [30] and Soliman et al. [31], with average ages of 63 and 61 years, respectively. Similar results have also been reported by other authors, such as Miller et al. in 2019 [32]. Postmenopausal bleeding was the most common symptom of EC. According to Vilouta et al. [33], approximately 80% of patients are menopausal, which is similar to the 86.2% observed in our sample .

The median BMI in our sample was similar to that reported by Burbos et al. [34], with an average BMI of 31.00 kg/m2. However, Burbos et al. [34] reported that 38% of the patients had high blood pressure, compared to 57.2% in our study, and 17% had diabetes, compared to 26.2% in our study. The higher prevalence of these conditions in our study may be attributed to differences in the time period and population characteristics [34].

In our sample, the most frequent histological type was endometrioid, with a slightly higher incidence than that reported by Verrier et al. [35], who also identified endometrioid as the most common type but with a lower incidence (71.4%). This difference may be explained by the higher BMI of the women included in our study [35].

Furthermore, Verrier et al. [35] described that the second most frequent histological type is clear cell, with an incidence of 22%. In our case, however, the second most frequent was serous-papillary tumor (10%), which is consistent with findings from the ASTEC study [36]. We also found differences in the degree of differentiation. In their study, G1 was the most frequent (51%), followed by G3 (34%). However, in our study, G2 was the most common (42%), closely followed by G1 (40.2%). When comparing the FIGO stage distribution with that of our sample with the ASTEC study, we observed similar percentages in early stages, with stage I accounting for 81% in our study versus 78–81% in the ASTEC study.

We found an EC-specific OS of 91.3% at 5 years and 84.8% at 10 years. Our 5-year OS is notably higher than the 83.8% recently reported by Montoya-González et al. in Colombia [37]. This difference may be partly explained by the fact that patients in our study were diagnosed at earlier stages. The authors reported that 61.5% of their patients were diagnosed at FIGO stage I, compared to 81% in our sample.

In the United States, the 5-year relative survival rate for EC (all stages combined) is 81%, rising to 95% for patients diagnosed at stage I [38]. Again, the difference in the proportion of patients diagnosed at stage I may account for these disparities (81% in our series vs. 67% in the United States, as reported by the National Cancer Institute [39]).

Regarding PFS, early stages presented a better prognosis compared to advanced stages. These results are consistent with previous publications, such as the study by Castelo Fernández et al. [40], which reports a PFS of 90% for stage I, 83% for stage II, and 43% for stage III.

Li et al. [41] reported a 5-year PFS of 83.3%. When analyzing 5-year PFS by stage, they found 94.9% for stage I, compared to 92.7% in our study; 93.7% for stage II, compared to 75.1% in our study; 62.8% for stage III, compared to 64.5% in our study; and 15.4% for stage IV.

Among the factors included in the multivariate analysis, the one that showed the greatest impact on OS was being over the age of 60 at the time of diagnosis. Additionally, we found that OS is closely dependent on the stage at diagnosis, with lower survival rates in patients with more advanced stages (III to IV). It has also been demonstrated that the more undifferentiated the tumor, the lower the OS. On the other hand, patients with serous-papillary tumors had a lower probability of survival compared to those with endometrioid tumors. Our results contrast with those observed in previous studies, such as that of Matsubara et al. [42], which found through multivariate analysis that the stage at diagnosis is the independent clinical factor most influencing OS. In that study, being in stage III–IV versus stage I–II was associated with a HR of 9.08 (95% CI: 4.83–17.03), which appears to be higher than in our study. In that study, patients with G3 tumors present a relative risk of dying with a HR 2.18 (95% CI: 1.03–4.62), compared to patients G1–G2. In contrast, our study found that patients with G3 tumors had an HR of 6.28 (95% CI: 1.18 to 33.51) compared to those with G1 tumors. Other variables, such as histological type, the presence of lymph node metastases, and peritoneal cytology, were also analyzed but were not found to be significant. That study also asserts that the key factors influencing PFS are tumor stage and histological type. Specifically, a stage III–IV tumor compared to a stage I–II tumor was associated with a HR of 5.01 (95% CI: 3.06–8.19), similar to our findings. However, their study differs from ours in that they found the non-endometrioid histological type to be significantly associated with lower PFS compared to the endometrioid type, with a HR of 1.97 (95% CI: 1.08–3.57).

Our study has several limitations. The first is its retrospective nature, which means we are limited to analyzing the information available in medical records. Additionally, as a case series without a comparison group, our study cannot establish causal relationships. Finally, the management of EC has evolved in recent years. This means that some factors now known to impact prognosis, such as certain molecular factors, were not determined at the beginning of the period covered by our study.

The main strength of the study lies in the extensive study period, which enables us to estimate EC survival 10 years after the initiation of treatment.

Our study shows that being 60 years or older at the time of diagnosis, advanced FIGO stages (II–IV), non-endometrioid EC, higher tumor histological grade (G2 and G3 vs. G1), and lymphovascular space invasion are associated with lower OS and PFS rates. Additionally, our multivariate analysis demonstrates that being 60 years or older, having a high tumor grade, advanced FIGO stage, and serous-papillary tumors are independent risk factors for recurrence or death in EC.

This study should serve as a foundation for further research that incorporates relevant aspects of the molecular biology of EC to refine patient prognosis. This approach will enable us to provide personalized and appropriate care based on the specific characteristics of each patient’s disease.

EC, endometrial cancer; OS, overall survival; PFS, progression free survival; FIGO, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics; AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer; TNM, tumor node metastases; BMI, body mass index; HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; G1, low differentiation grade; G2, moderate differentiation grade; G3, high differentiation grade; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author [MCL].

JJFA designed the research study. IVT, LDPZ, JJFA and MCL performed the research. CVF and CVR provided help and advice on data curation. JJFA, CVF and CVR analyzed the data. IVT, LDPZ, JJFA and MCL wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to editorial changes in the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The protocols of the University Hospital of Puerto Real (Cadiz, Spain) on the publication of patient data have been followed. The patient privacy has been respected. The researchers obtained consent for publication from the patients. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was performed according to ethics committee approval. The research protocol was approved on March 4, 2022 by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Cádiz (ethic approval number: 0177-N-22).

We would like to thank all the women who kindly agreed to participate in this study and extend our gratitude to the gynecology and nursing staff of the Department of Oncological Gynecology at Hospital Puerto Real for their hard work and dedication.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.