1 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University, 250021 Jinan, Shandong, China

2 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Dongming Maternal and Child Health Hospital, 274500 Dongming, Shandong, China

3 Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, People’s Hospital of Tongzhou Bay Demonstration Zone, 226399 Nangtong, Jiangsu, China

Abstract

Neonates born to women with severe preeclampsia (PE) exhibited lower Apgar scores. The purpose of this study was to evaluate the association between low Apgar scores and maternal, prenatal, and intrapartum variables in patients with severe PE.

A retrospective case–control study was conducted in a public teaching hospital from January 2016 to June 2022. Cases included patients with severe PE and an Apgar score below 7 at 1 or 5 minutes, while controls had severe PE with an Apgar score of 7 or higher. A total of 125 cases and 303 controls were included. Fisher's exact test, logistic regression and receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis were used as appropriated.

22 potential risk factors were assessed, of which 12 were significantly associated with changes in outcome. Multivariate analysis identified gestational age at delivery (GAD) (odds ratio [OR], 0.570; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.420–0.774; p < 0.001), intravenous anesthesia (OR, 12.889; 95% CI, 3.820–43.486; p < 0.001) and PE onset weeks (OR, 0.937; 95% CI, 0.879–0.999; p = 0.047) as independent risk factors for low Apgar scores in neonates with severe PE. The accuracy of predicting low Apgar scores in newborns of PE patients was high based on GAD (area under the curve [AUC], 0.868; 95% CI, 0.832–0.905; p < 0.001) and PE onset weeks (AUC, 0.785; 95% CI, 0.741–0.828; p < 0.001).

The GAD (<30.5 weeks) and PE onset weeks (<28.5 weeks) are identified as risk factors for low Apgar scores in newborns of patients with severe PE, and general anesthesia is suggested to be avoided during delivery.

Keywords

- severe preeclampsia

- low Apgar score

- gestational age at delivery

- PE onset weeks

Preeclampsia (PE) is a pregnancy-specific disorder characterized by hypertension

and proteinuria, significantly affecting the health of both the mother and the

fetus. It is estimated that 4.6% of pregnancies worldwide are affected by PE [1, 2]. The pathophysiological changes in PE involve vasoconstriction and endothelial

dysfunction throughout the body, resulting in reduced perfusion to various organs

and posing risks to both mother and fetus [3]. Inadequate remodeling of uterine

spiral arteries leads to decreased placental perfusion, a reduced mean diameter

of these vessels, and endothelial injury, which impairs placental function and

results in fetal distress. PE is closely related to adverse outcomes such as

cesarean delivery, placental abruption, small for gestational age (SGA) infants,

preterm birth, and a 5-minute Apgar score

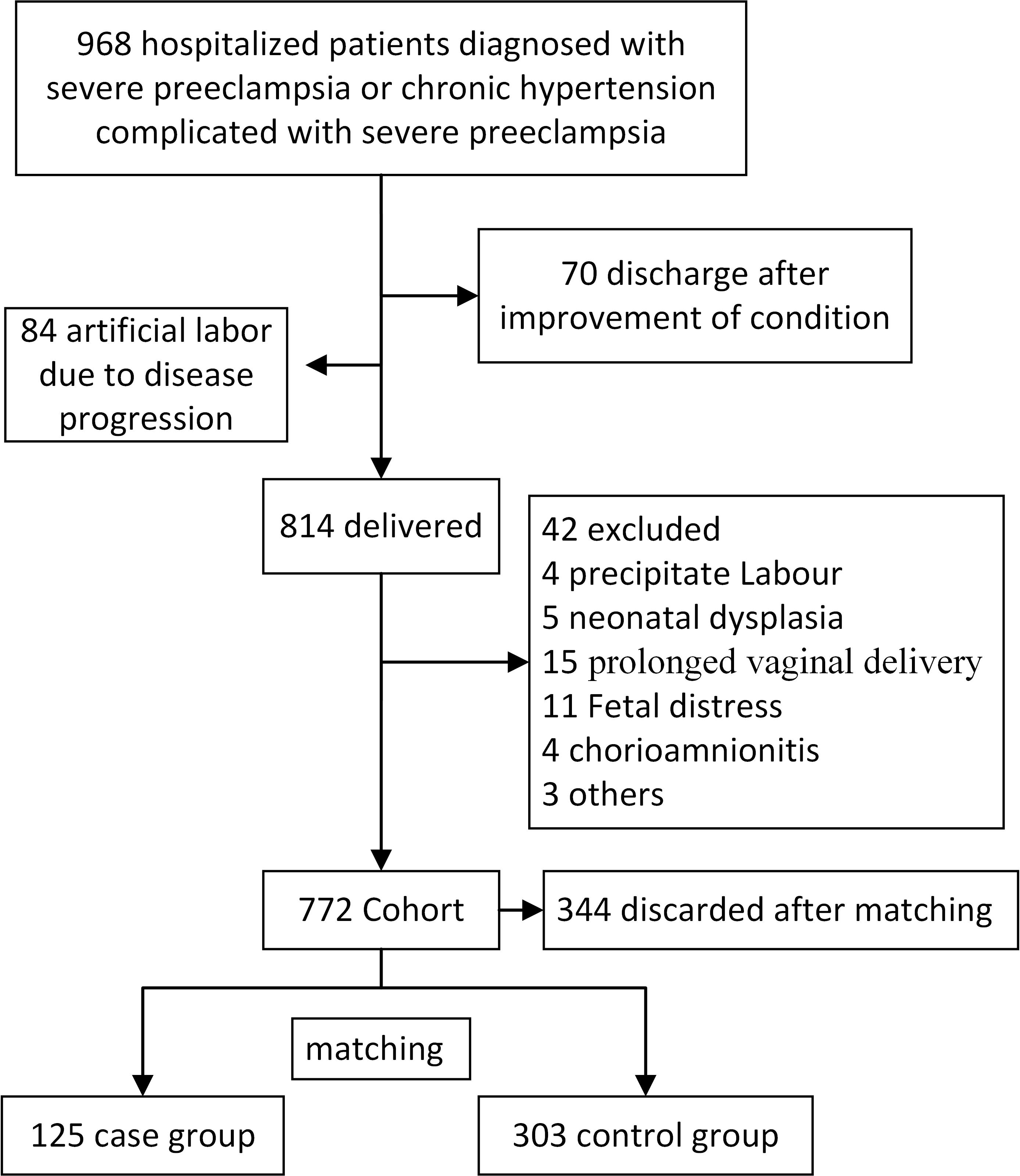

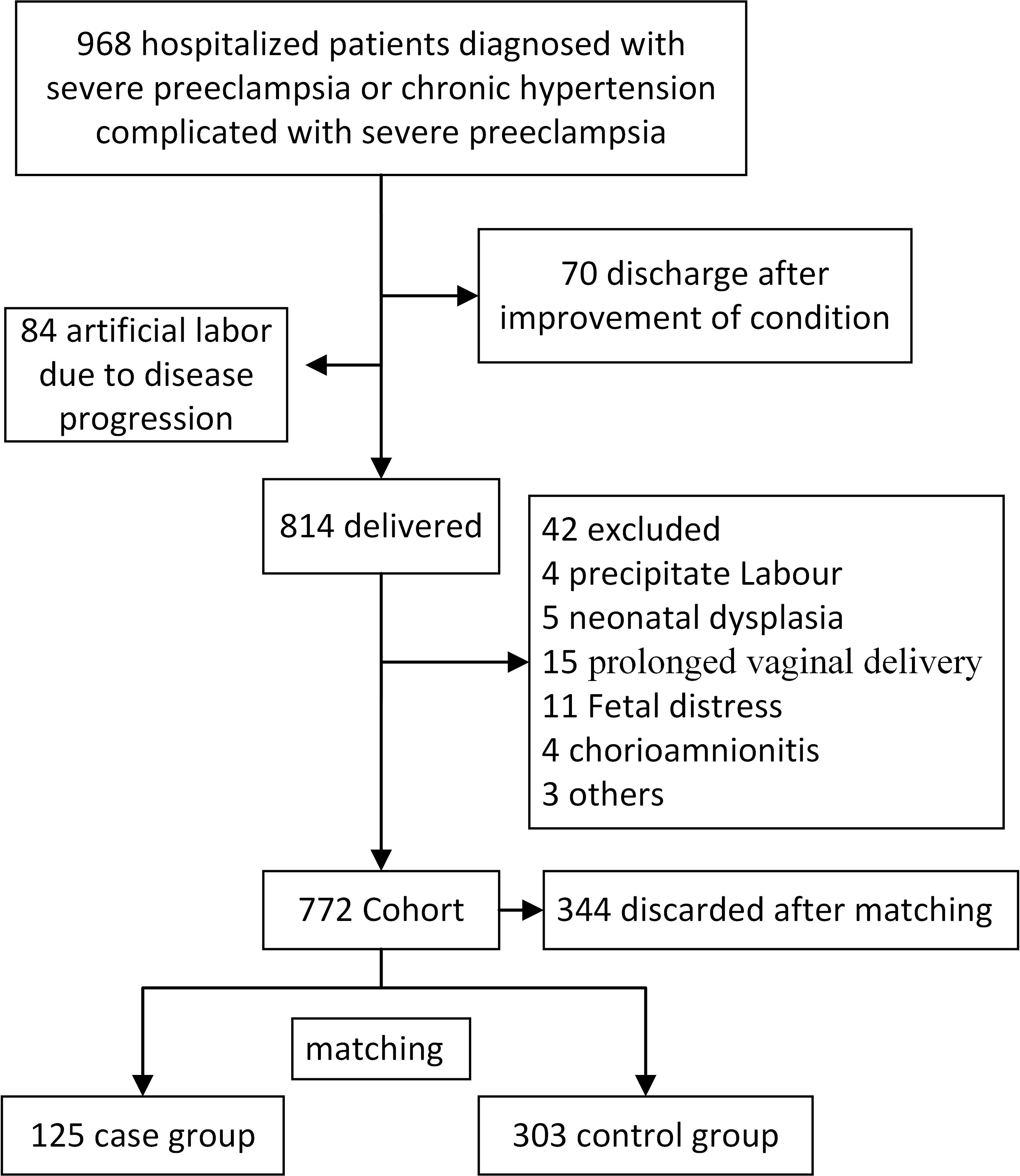

We conducted a retrospective case–control study at Shandong Provincial

Hospital, affiliated with Shandong First Medical University. We reviewed the

database for patients diagnosed with severe PE or chronic hypertension

complicated by severe PE, between January 2016 and June 2022 (Fig. 1). Of the 968

cases, 70 were discharged after treatment, and 84 underwent labor induction.

Ultimately, 814 pregnant patients eventually gave birth, and the Apgar scores of

their newborns were assessed. Exclusion criteria included fetal anomalies, fetal

distress, abnormal fetal positioning during delivery, chorioamnionitis, and

prolonged or rapid vaginal delivery. A total of 772 cases were included in this

study, from which 125 cases with Apgar scores

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Patient flow diagram. A representation of the process involved in the inclusion, exclusion, and grouping.

3 obstetricians conducted an additional clinical evaluation of the patients and

confirmed the diagnosis of PE. Chronic hypertension combined with PE: patients

with chronic hypertension present with evidence of new-onset proteinuria,

additional maternal organ dysfunction, or uteroplacental dysfunction. PE:

gestational hypertension (systolic blood pressure

Severe PE: systolic blood pressure

Abnormal pregnancy history includes previous history of pregnancy loss, recurrent pregnancy loss, stillbirth, neonatal death, or fetal development abnormalities. We defined SGA as a birth weight below the 10th percentile on the Fenton growth chart or fetal weigh of less than 2500 g at or beyond 37 weeks of gestation [11]. Premature rupture of membranes is defined as the spontaneous rupture of the fetal membranes prior to the onset of labor [12]. Clinical evaluation of placental abruption was based on the presence of prenatal uterine tenderness and vaginal bleeding, with confirmation through placental examination following delivery [13]. The diagnostic criteria of antiphospholipid syndrome (APS) followed the Sydney criteria [14], and pregestational diabetes mellitus (PGDM), gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) according to the recommendations of the International Association of Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Groups [14, 15]. Abnormal fetal umbilical artery flow was defined as the absence of end-diastolic blood flow or the presence of reversed end-diastolic flow. Anesthesia for cesarean sections included both intraspinal and general anesthesia. This research was approved by the Biomedical Research Ethics Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital prior to its initiation (Approval No. SWYX-21).

Statistical analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Comparisons of categorical variables were performed with

Fisher’s exact test, and continuous variables with Mann-Whitney

U test. Logistic regression model was used to analyze the risk factors associated

with low Apgar scores. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis

was used to determine cutoff values. Statistical significance was set at

p

Of the 772 patients with severe PE, 125 (16.19%) delivered infants with low

Apgar scores. A total of 22 variables were assessed, encompassing potential risk

factors such as maternal clinical variables, complications during pregnancy, and

both maternal and neonatal variables during delivery. As presented in Table 1, a

total of 12 variables were found to be significantly associated with changes in

the outcome. The gestational weeks at which PE occurred was significantly lower

in the case group compared to the control group (median 27.0 weeks [interquartile

range (IQR), 24.0–28.0] vs. median 31.0 weeks [IQR, 28.0–34.0], p

| Score |

Score |

p | |

| Age, median (year, IQR) | 33.0 (29.0, 36.0) | 33 (30.0, 36.0) | 0.433 |

| PE onset weeks (week) | 31.0 (28.0, 34.0) | 27.0 (24.0, 28.0) | |

| History of PE | 25 (8.3%) | 19 (15.2%) | 0.036 |

| Abnormal pregnancy history | 48 (15.8%) | 30 (24.0%) | 0.054 |

| BMI, median (kg/m2, IQR) | 31.5 (28.2, 35.0) | 29.9 (27.3, 33.5) | 0.059 |

| GDM or PGDM | 84 (27.7%) | 15 (12.0%) | |

| APS | 6 (2.0%) | 3 (2.4%) | 0.724 |

| LWMH | 22 (7.3%) | 8 (6.4%) | 0.838 |

| LDA | 17 (5.6%) | 4 (3.2%) | 0.338 |

| Magnesium sulfate application | 201 (66.3%) | 81 (64.8%) | 0.823 |

| Dexamethasone application | 165 (54.5%) | 85 (68.0%) | 0.010 |

| Serum creatinine (µmol/L) | 60.15 (50.0, 69.2) | 63.32 (52.3, 77.4) | 0.007 |

| Serum uric acid (mmol/L) | 414.5 (344.0, 476.9) | 421.0 (367.5, 593.2) | 0.102 |

| HELLP | 16 (5.3%) | 23 (18.4%) | |

| Premature rupture of membrane | 10 (3.3%) | 2 (1.6%) | 0.522 |

| Placental abruption | 10 (3.3%) | 10 (8.0%) | 0.045 |

| SGA | 120 (39.6%) | 82 (65.6%) | |

| Abnormal fetal umbilical artery blood flow | 21 (6.9%) | 29 (23.2%) | |

| Gestational weeks at delivery (week) | 34.0 (31.0, 36.0) | 29.0 (28.0, 30.0) | |

| Vaginal delivery | 7 (2.3%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0.111 |

| Birth weight of neonates (g) | 1980.0 (1400.0, 2610.0) | 980.0 (850.0, 1320.0) | |

| General anesthesia | 16 (5.3%) | 44 (35.2%) |

PE, preeclampsia; IQR, interquartile range; BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; PGDM, pregestational diabetes mellitus; APS, antiphospholipid syndrome; LMWH, low molecular weight heparin; LDA, low-dose aspirin; HELLP, Hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes and low platelets; SGA, small for gestational age.

GAD in the case group was significantly lower than the control group (median

29.0 weeks [IQR, 28.0–30.0] vs. 34.0 weeks [IQR, 31.0–36.0], p

The 14 variables with p

| B | S.E. | Wald | p | Exp(B) | 95% CI | ||

| Lower | Upper | ||||||

| PE onset weeks | –0.065 | 0.033 | 3.960 | 0.047 | 0.937 | 0.879 | 0.999 |

| GAD | –0.561 | 0.156 | 12.999 | 0.000 | 0.570 | 0.420 | 0.774 |

| General anesthesia | 2.556 | 0.620 | 16.975 | 0.000 | 12.889 | 3.820 | 43.486 |

| SGA | 0.836 | 0.464 | 3.251 | 0.071 | 2.308 | 0.930 | 5.729 |

PE, preeclampsia; CI, confidence interval; GAD, gestational age at delivery; SGA, small for gestational age; B, regression coefficient; S.E., standard error; Exp(B), the exponent of B.

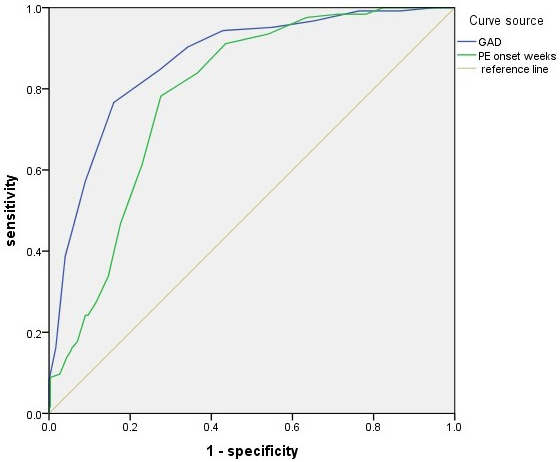

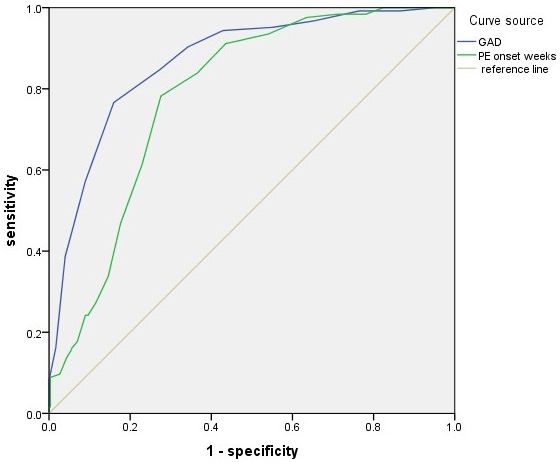

ROC analysis results demonstrated high accuracy in predicting low Apgar score

based on GAD (area under the curve [AUC], 0.868; 95% CI, 0.832–0.905;

p

| Factor | AUC | 95% CI | Cutoff values | Sensitivity% | Specificity% | p |

| GAD | 0.868 | 0.832–0.905 | 30.5 weeks | 76.6 | 84.1 | |

| PE onset weeks | 0.785 | 0.741–0.828 | 28.5 weeks | 78.2 | 72.4 |

GAD, gestational age at delivery; PE, preeclampsia; CI, confidence interval; AUC, area under the curve.

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

ROC curve analysis for GAD (AUC, 0.868; 95% CI, 0.832–0.905;

p

Pregnant patients with PE often undergo early termination of pregnancy due to factors such as placental hypoperfusion, elevated maternal blood pressure, disease progression, and other related complications. Consequently, their newborns exhibit a higher incidence of low Apgar scores compared to those born to mothers without complications. In univariate analysis, patients with low Apgar scores in newborns exhibited higher rate of a history of PE, earlier onset of PE, shorter GAD, and lower birth weight compared to those with high Apgar scores. This association is thought to be related to premature termination of pregnancy in patients with PE. Patients with low Apgar scores also exhibited an increased rate of dexamethasone administration, likely due to the earlier delivery time. Additionally, the incidence of HELLP syndrome, abnormal umbilical cord blood flow, placental abruption, and SGA infants increased during pregnancy. This group of patients also exhibited elevated creatinine levels and an increased rate of general anesthesia use.

In this study, multivariate analysis revealed that the GAD was an independent

risk factor for low Apgar scores in cases of PE. The risk of low Apgar score

decreased with increasing GAD, highlighting that gestational age is a crucial

determinant of newborn Apgar scores. Santos et al. [16] found a positive

association between low Apgar scores and GAD of less than 37 weeks pregnant

patients without PE. Svenvik et al. [17] reported that 62% of preterm

infants younger than 28 weeks had a 5-minute Apgar score of 7. The sensitivity

and specificity for predicting low Apgar score at 1 minute in gestational age

Patients with early onset PE experienced significantly unfavorable perinatal outcomes, including lower 5-minute Apgar scores [2]. This study demonstrated that the gestational week at which PE onset occurs has good accuracy in predicting low Apgar scores. The optimal diagnostic cutoff point was determined as 28.5 weeks of gestation, with a sensitivity of 77.3%, and a specificity of 69.9%. The probability of low Apgar scores in neonates with gestational age greater than 28.5 weeks was significantly reduced.

Pregnant patients with diabetes mellitus are at an increased risk of developing PE. Many of these patients also have longer diabetes duration, poor glycemic control, and microvascular complications, such as type I diabetes, diabetic nephropathy, and retinopathy [19, 20, 21]. In this study, while some patients with GDM and PGDM were included, these conditions were not identified as independent risk factors for the delivery of infants with low Apgar scores. The short duration of diabetes and glycemic control may not significantly increase the risk of low Apgar scores in cases of severe PE.

In this study, the cesarean section rate was found to be as high as 98%. Previous studies have reported higher cesarean section rates among pregnant patients with PE compared to vaginal delivery [22, 23]. This disparity is believed to be attributed to maternal factors and an immature cervix in these individuals. Pregnant patients who underwent general anesthesia for cesarean sections had a significantly higher risk of low Apgar scores compared to those who underwent intraspinal anesthesia [24, 25, 26]. Additionally, a significantly elevated incidence of birth asphyxia was observed in infants born to mothers with severe PE who received general anesthesia [27]. Our data demonstrated that general anesthesia affected neonatal Apgar scores in cases of PE, which is consistent with previous findings. In pregnant patients diagnosed with PE, particularly those who undergo preterm delivery, the use of intraspinal anesthesia may help to reduce the occurrence of this condition.

Previous literature has reported that newborns delivered from patients with severe PE have lower birth weight and higher neonatal asphyxia rate [9, 28]. In this study, the incidence of neonatal SGA in neonates born to pregnant patients with PE was significantly increased, consistent with previous literature reports. Some researchers found in their univariate analysis that the incidence of neonatal mild asphyxia increased in pregnant patients with PE combined with fetal growth restriction (FGR) [29]. Kovo et al. [30] compared the Apgar scores of pregnant women with gestational hypertension combined with FGR and to those with normal blood pressure, finding no significant difference between the two groups. Multifactor analysis in this study demonstrated that SGA was not an independent risk factor for low Apgar scores, despite a p-value of 0.071.

The limitation of this study is that it is a single-center study, and due to the low incidence of severe PE, the data for the case group is small. Some very low birth weight neonates were not followed up, and the long-term neonatal outcomes were not included in the study. In the future, we will focus on improving follow up, expanding the data volume, and obtaining more comprehensive neonatal outcome data.

The GAD (

The data are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

YW, JM, BC, JZ and SY designed the research study. YW and JM drafted the work. BC, JZ and SY reviewed it critically. YG and CW acquired, analyzed date and reviewed content. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. All authors have participated sufficiently in the work and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of Biomedical Research Ethic Committee of Shandong Provincial Hospital before commencing (approval number: NO. SWYX-21). Our study was retrospective with data from the medical record system, and it was approved for waivers of informed consent.

We wish to extend our sincere appreciation to all those who provided assistance during the composition of this manuscript. Our gratitude also goes out to the peer reviewers for their invaluable feedback and suggestions.

This study was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC2705900), clinical Science and Technology Innovation Program of Ji’nan (202328072), medical technology innovation incentive program of Shandong Provincial Hospital Affiliated to Shandong First Medical University (CXJL: ZQN – 202209), Shandong Provincial Natural Science Foundation (ZR2024MH314), and Study on the prediction model of severe PE based on fetal free DNA content in peripheral blood of pregnant women (Company cooperation project).

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.