1 Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, Mardin Artuklu University Faculty of Medicine, 47100 Mardin, Turkey

2 Department of Perinatology, Selcuk University Faculty of Medicine, 42005 Konya, Turkey

3 Obstetrics and Gynecology Department, Siirt Training and Research Hospital, 56100 Siirt, Turkey

4 Internal Medicine Department, Siirt Training and Research Hospital, 56100 Siirt, Turkey

Abstract

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a common metabolic disorder characterized by glucose intolerance that develops during pregnancy. The underlying pathophysiological mechanisms of GDM involve complex interactions between genetic, environmental, and hormonal factors, including adipokines secreted by visceral adipose tissue. Omentin, vaspin, and visfatin are adipokines believed to influence insulin sensitivity and inflammation, though their precise relationship with GDM remains unclear. This study aimed to examine the association between these adipokines and GDM.

This single-center, prospective controlled cohort study included 87 pregnant patients diagnosed with GDM via an oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) between the 24th and 28th weeks of gestation, along with 87 control subjects without GDM. Serum levels of omentin, vaspin, and visfatin were measured using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA), and their association with GDM was analyzed.

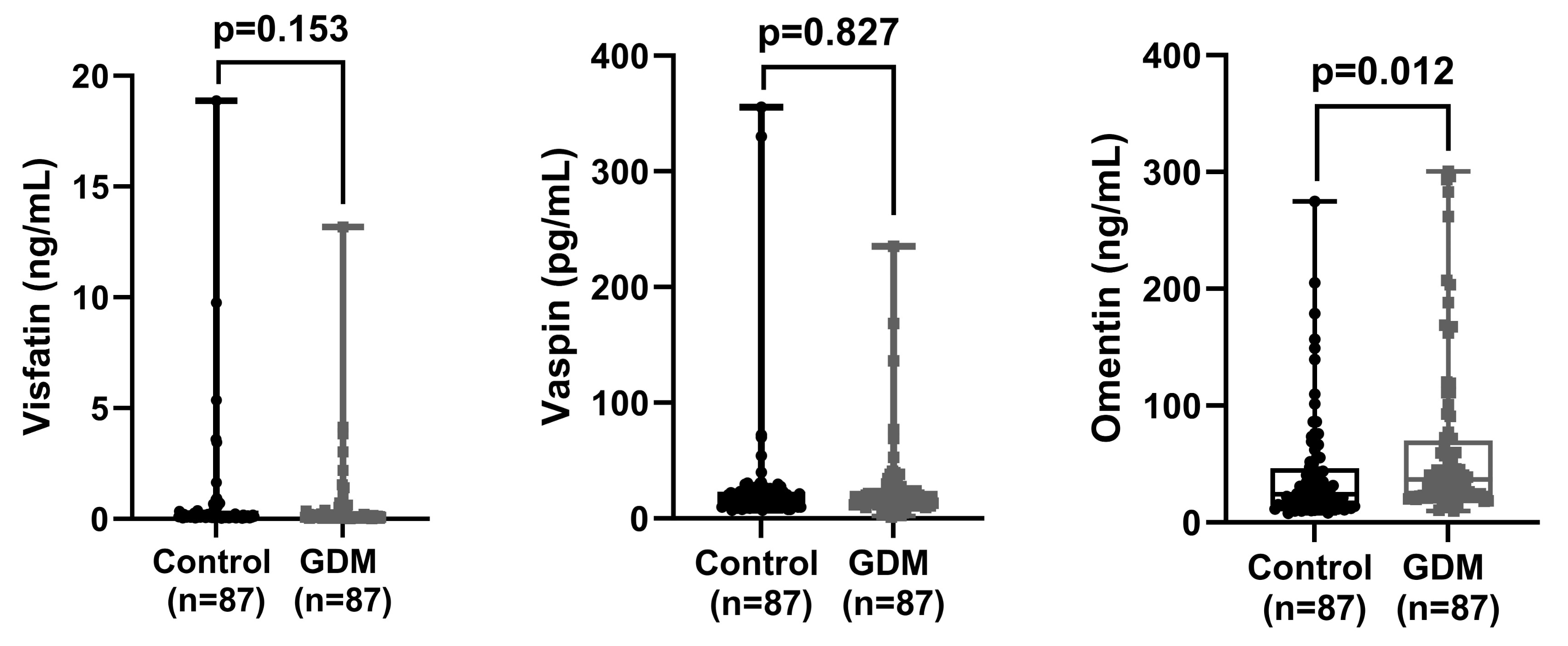

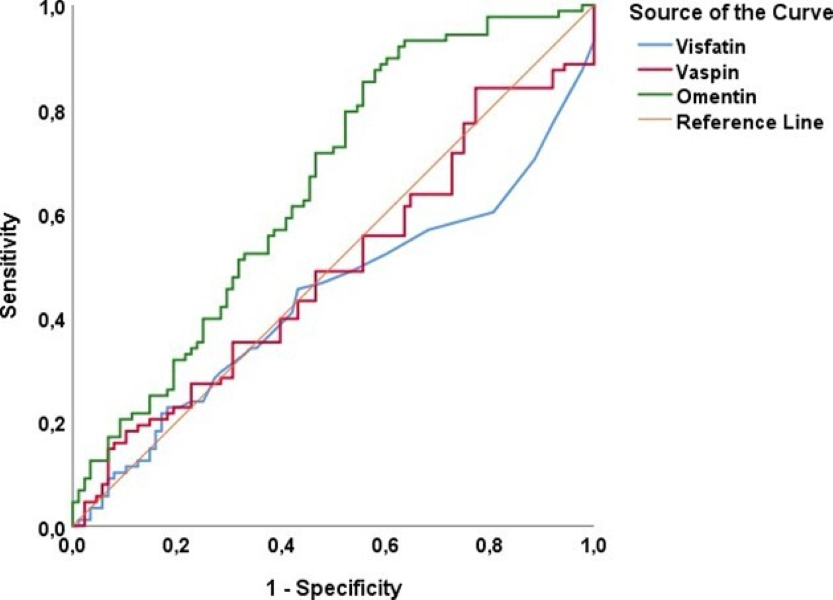

Our results demonstrated that omentin levels were significantly higher in the GDM group compared to the control group (p = 0.012), while no significant differences were observed in vaspin and visfatin levels (p > 0.05). An omentin cut-off value of 29.0 ng/mL predicted GDM with 59.1% sensitivity and 59.1% specificity, suggesting its potential as a biomarker for GDM.

This study underscores the unique role of omentin in GDM, in contrast to the non-significant changes observed in vaspin and visfatin levels. The elevated omentin levels in GDM patients suggest its potential as a biomarker for diagnosing and managing GDM. Further research is needed to elucidate the mechanisms through which omentin contributes to the pathophysiology of GDM.

NCT05463237, https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT05463237.

Keywords

- gestational diabetes mellitus

- pregnancy

- omentin

- vaspin

- visfatin

Gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) is a complex condition, and its pathophysiology has not yet been fully elucidated. Insulin resistance and impaired insulin production in the pancreas are significantly influenced by the amount of fat mass present during pregnancy, and these factors play a crucial role in the development of GDM. Adipokines secreted by adipose tissue can contribute to chronic diseases, exacerbate insulin resistance, and potentially influence the pathways leading to GDM [1, 2, 3, 4]. Visceral adipose tissue is one of the most metabolically active types of fat accumulated and serves as the primary source of various adipokines, such as omentin, vaspin, and visfatin. These adipokines play important roles in the pathophysiology of GDM, given their accessibility and abundance in visceral fat [5]. One of these 3 adipokines, omentin, increases insulin production, thus promoting metabolic health. It contains anti-inflammatory properties and increases insulin production, improving glucose metabolism. However, low omentin levels in GDM patients suggest that omentin deficiency may be involved in the development of GDM [6, 7, 8, 9].

Vaspin has an antidiabetic value that increases insulin levels. Low vaspin levels in GDM suggest that it may play a rapid regulatory role in counteracting insulin resistance [10]. However, there are also results that vaspin has on insulin resistance.

Visfatin exhibits insulin-like effects. It can regulate glucose distribution by binding to the insulin receptor and increase insulin levels. While some studies continue to suggest that visfatin may play a role in the regulation of GDM, others argue that it is increased by overweight/obesity and may not be directly related to GDM [11].

This suggests that the visceral fat tissue as a whole plays a role in the pathophysiology of GDM and that adipokines secreted from this tissue contribute to GDM, and therefore may be considered as a potential treatment target. However, among the studies on the role of adipose status in the pathogenesis of GDM, there is no consensus yet on the specific properties and units of adipokines. In this context, this study aimed to investigate the roles of omentin, vaspin and visfatin secreted from visceral adipose tissue in GDM patients.

The aim of this investigation was to conduct a prospectively designed study. The study protocol was approved by the Siirt University Ethics Committee (2022/09/01/01; ClinicalTrials.gov ID: NCT05463237). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles stated in the Declaration of Helsinki, and written informed consent was obtained from the patients participating in the study. The study group consisted of pregnant patients diagnosed with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) between the 24th and 28th weeks of pregnancy utilizing a 100-gram oral glucose tolerance test (100-g OGTT). These diagnoses were made between May 2022 and May 2023 at the Siirt University Training and Research Hospital, a tertiary hospital in Siirt province. Adipokine samples in maternal blood were collected at the time of GDM diagnosis, i.e., between the 24th and 28th weeks of pregnancy. The gestational week was recorded as the week when GDM was diagnosed and the serum samples were collected.

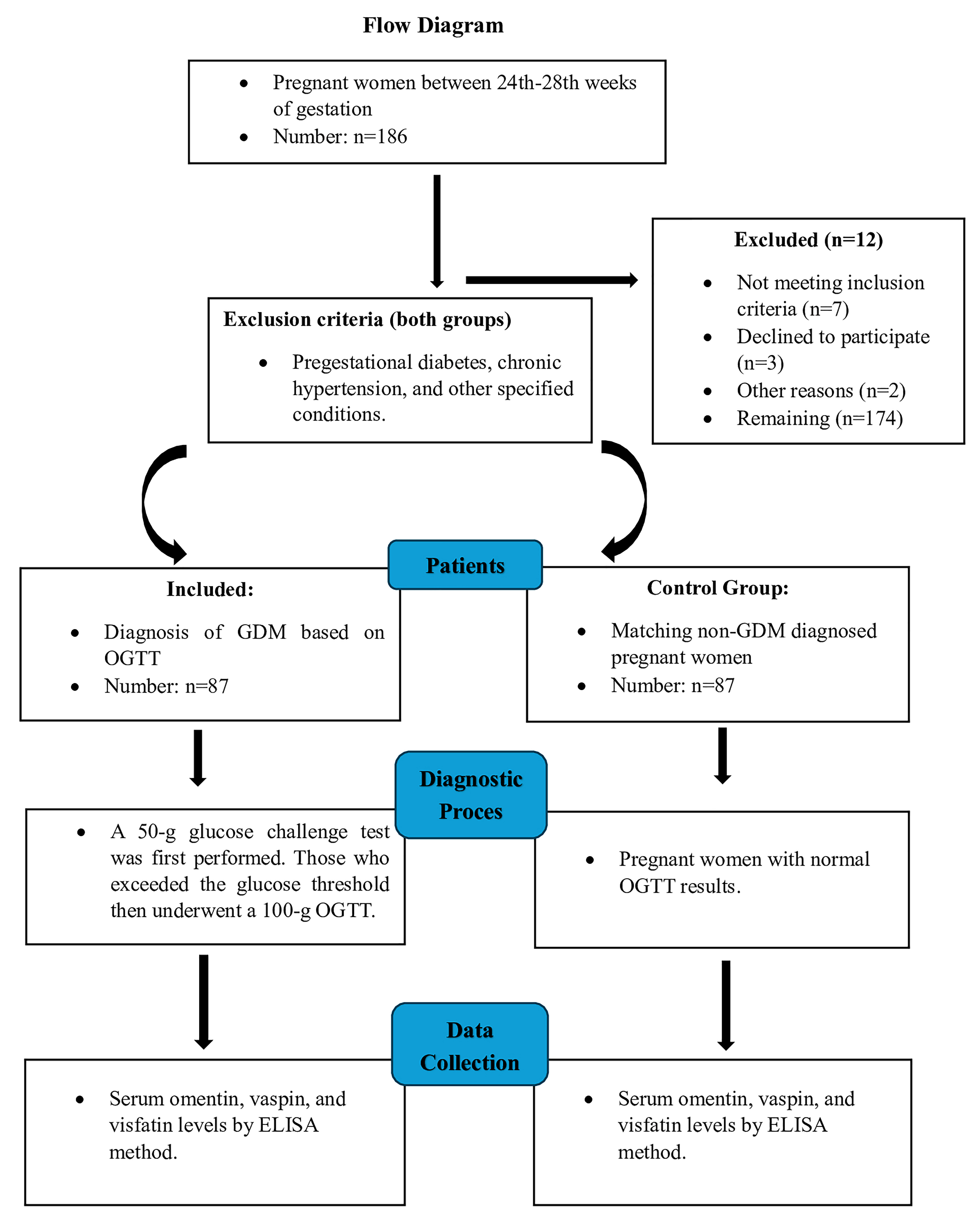

GDM was diagnosed using the oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT) according to the guidelines set by the American Diabetes Association (ADA). The test was performed in two stages between the 24th and 28th weeks of pregnancy. First, all participants were given 50 grams of glucose solution and plasma glucose levels were measured one hour later. Plasma glucose levels were considered elevated if they exceeded 140 mg/dL at the end of the one-hour period. Participants whose plasma glucose levels exceeded this threshold underwent a more comprehensive diagnostic test and were given 100 grams of glucose solution. Fasting glucose levels were determined as 95 mg/dL and plasma glucose levels were measured one hour, two hours and three hours after consuming the glucose solution. Threshold plasma glucose values were determined as 180 mg/dL, 155 mg/dL and 140 mg/dL for the first, second and third hours, respectively. Participants with glucose levels above the specified threshold values in at least two of these four measurements were diagnosed with GDM according to ADA criteria (American Diabetes Association, 2018) [12]. Participants with pre-gestational diabetes, chronic hypertension, chronic kidney disease, autoimmune diseases, thyroid disease, active infections, multiple pregnancies and fetal anomalies were not included in the study (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study design. GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test.

Power (1 –

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS 26.0 (Statistical Product and

Service Solutions for Windows, Version 26.0, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA, 2019)

software package. Descriptive statistics for the collected data were expressed as

mean

Triglyceride, HbA1c, 1st, 2nd, and 3rd hours glucose levels and omentin levels were found to be significantly higher in the patient group compared to the control group (p

| Variables | Control (n = 87) | GDM (n = 87) | p-value | |||

| Mean |

Median (IQR) | Mean |

Median (IQR) | |||

| Triglyceride (mg/dL) | 203.8 |

189 (83) | 231.6 |

215 (110) | 0.043 | |

| HDL (mg/dL) | 79.8 |

77 (19) | 81.5 |

76 (25) | 0.677 | |

| LDL (mg/dL) | 124.5 |

120 (41) | 123.2 |

122 (40) | 0.775 | |

| Cholesterol (mg/dL) | 202.8 |

199 (54) | 212.6 |

211 (56) | 0.118 | |

| Insulin (mU/L) | 27.1 |

15.7 (30.8) | 35.4 |

27.3 (37.7) | 0.026* | |

| HbA1c (%) | 5.2 |

5.2 (0.4) | 5.4 |

5.3 (0.5) | 0.001 | |

| Glucose (mg/dL) | ||||||

| (1) Hour | 123.6 |

124 (28) | 198.9 |

194 (30) | ||

| (2) Hour | 108.0 |

110 (21) | 159.8 |

157 (34) | ||

| (3) Hour | 81.7 |

81 (12) | 95.6 |

92 (24) | ||

| Visfatin (ng/mL) | 0.6 |

0.1 (0.1) | 0.5 |

0.1 (0.2) | 0.153* | |

| Vaspin (pg/mL) | 26.6 |

17.6 (11.4) | 24.6 |

16.6 (11.9) | 0.827* | |

| Omentin (ng/mL) | 41.5 |

24.1 (31.6) | 64.4 |

36.8 (47.2) | 0.012* | |

| Age (Years) | 30.2 |

30 (8) | 30.3 |

30 (6) | 0.849 | |

| BMI (kg/m2) | 27.4 |

27 (6) | 28.6 |

28 (7) | 0.079 | |

| Gravity | 3.8 |

3 (1) | 4.1 |

4 (4) | 0.730 | |

| Parity | 2.2 |

2 (0) | 2.3 |

2 (2) | 0.466 | |

| Gestational weeks | 26.5 |

26 (1) | 26.6 |

27 (2) | 0.695 | |

| Ectopic (No) n, (%) | 87 (98.9) | 86 (97.7) | 0.605 | |||

| Missed (No) n, (%) | 88 (100) | 80 (90.9) | 0.039 | |||

| Abortus (No) n, (%) | 61 (69.3) | 57 (64.8) | 0.382 | |||

| Smoking (Yes) n, (%) | 8 (9.1) | 15 (17.0) | 0.117 | |||

Independent t-test, Welch’s t-test and * Mann-Whitney U test were used.

p

Pearson’s chi-square test or Fisher’s exact chi-square test was used for categorical variables.

Gestational week: The week when GDM was diagnosed and serum samples were collected.

BMI, body mass index; GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; HDL, high-density lipoprotein; IQR, interquartile range; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; SD, standard deviation.

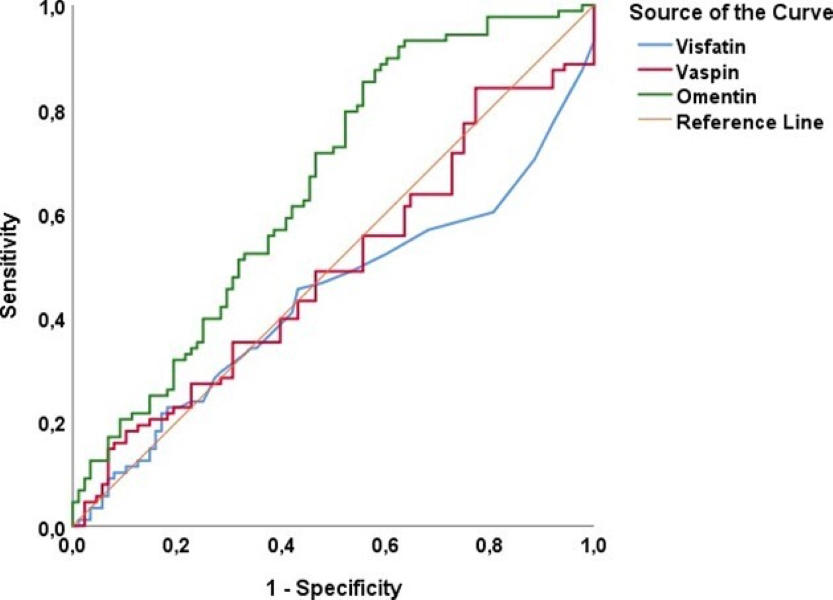

| Variables | AUC | SE | p-value | Asymptotic 95% CI | Sensitivity (%) | Specificity (%) | Cutoff value | |

| Lower Bound | Upper Bound | |||||||

| Visfatin (ng/mL) | 0.438 | 0.044 | 0.153 | 0.352 | 0.524 | 48.9 | 46.6 | 0.10 |

| Vaspin (pg/mL) | 0.490 | 0.044 | 0.827 | 0.404 | 0.576 | 48.9 | 53.4 | 17.7 |

| Omentin (ng/mL) | 0.654 | 0.041 | 0.574 | 0.735 | 59.1 | 59.1 | 29.0 | |

p

ROC analysis used and p

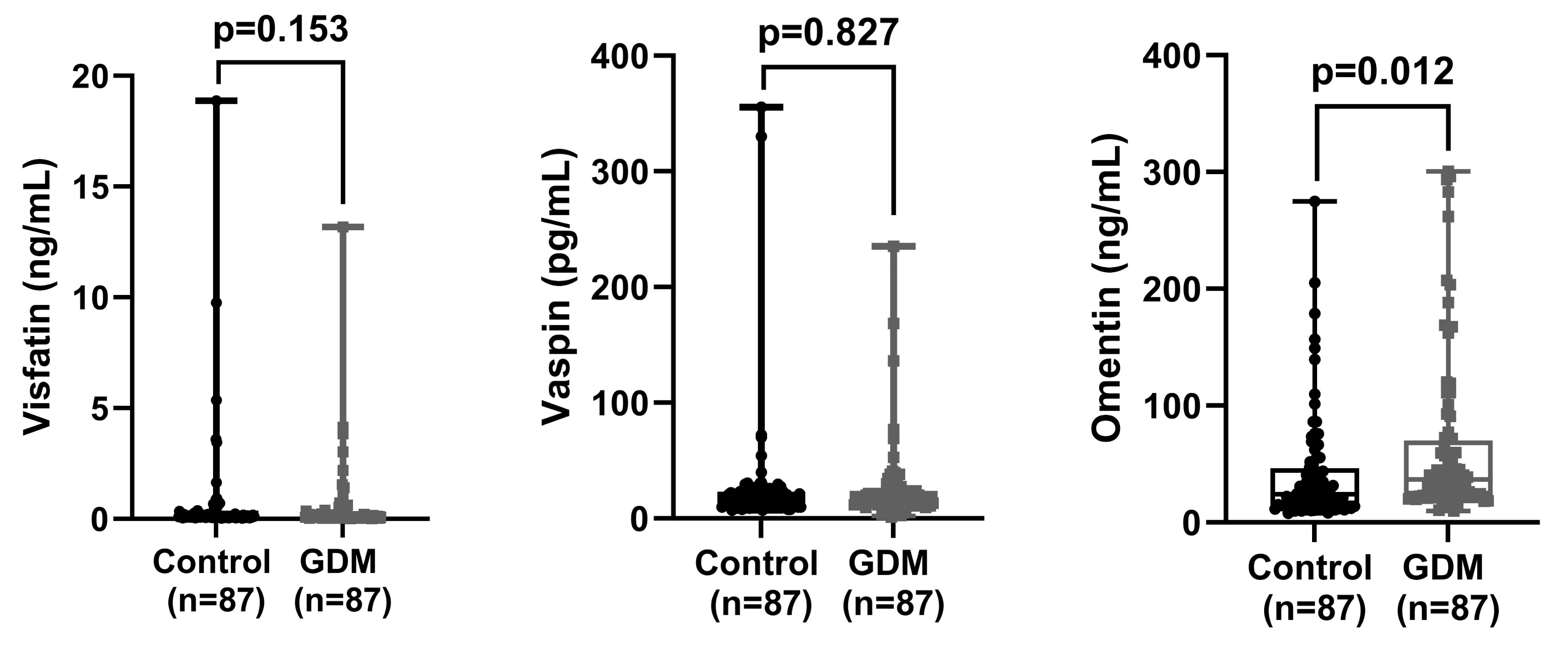

Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of visfatin, vaspin, and omentin values between control and GDM groups. GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus.

Fig. 3.

Fig. 3.

ROC analysis to determine the cut-off value for visfatin, vaspin, and omentin in predicting GDM. GDM, gestational diabetes mellitus; ROC, receiver operating characteristic.

In this study, we focused on 3 specific substances (adipokines) secreted from the abdominal fat tissue during pregnancy, namely omentin, vaspin and visfatin, which are associated with gestational diabetes (GDM). Since visceral fat tissue is known to play a central role in the development of GDM, we aimed to examine the effects of these substances produced by this tissue on GDM. While this focus limits the boundaries of our study, we did not forget that GDM has a wider range of biomarkers. The 24–28th weeks of pregnancy are a critical period when insulin resistance in the body increases significantly critical for the development of gestational diabetes. Adipokines such as omentin, vaspin and visfatin are closely related to insulin resistance and glucose metabolism, and measurements taken during these weeks can help detect the risk of GDM [13]. The levels of these adipokines can be used as biomarkers for the development and management of GDM, and measurements taken between the 24–28th weeks in particular can increase the accuracy of diagnosis and risk assessment [14]. Since these weeks are a period of rapid fetal growth, the development of GDM may pose risks for both mother and baby. Therefore, monitoring of adipokine levels may contribute to the management of these risks [15].

GDM is a major metabolic disorder that occurs during pregnancy and can affect both maternal and fetal health. Most studies have reported that omentin levels are lower in pregnant patients with GDM than in pregnant patients without GDM [16, 17, 18]. This condition has been associated with glucose and lipid metabolism disorders and insulin resistance [19, 20]. Omentin has been described as an adipokine with properties that increase insulin sensitivity and reduce inflammation, and it has been suggested that omentin levels may play an important role in the development of GDM [21]. However, in our study, omentin levels were found to be significantly higher in pregnant patients with GDM as compared to those without GDM, suggesting that omentin may play a different role in the development of GDM. These differences in omentin levels may be attributed to ethnic diversity and genetic factors [22]. These findings suggest that the relationship between omentin and GDM is more complex than previously thought, and that significant changes in omentin levels may be both a consequence and a cause of GDM. Therefore, the increase in omentin levels observed in pregnant patients with GDM may be a defensive response of the body against metabolic imbalances. This explanation is consistent with the findings in the literature indicating the insulin-sensitizing and inflammation-reducing effects of omentin [23, 24]. In addition, Pan et al. [25] suggested that omentin-1 levels are increased in pre-diabetic states, suggesting that this adipokine may increase insulin sensitivity and be secreted more as a defensive mechanism in the early stages of glucose intolerance.

However, the omentin cut-off point of 29.0 ng/mL identified in our study predicted GDM with 59.1% sensitivity and 59.1% specificity. These rates indicate that there are some limitations in using omentin as an effective biomarker for GDM. It is particularly important to note that 41% of patients with omentin levels above this cutoff point may not develop GDM. This situation suggests that the low sensitivity and specificity rates may limit the effectiveness of using omentin as an independent biomarker for diagnosing GDM. Furthermore, the low sensitivity and specificity of omentin indicate that further research is needed to validate its use as a biomarker in clinical practice. Therefore, more comprehensive validation of omentin’s diagnostic performance is required. To achieve this, studies with larger sample sizes and diverse populations should be conducted. In addition, the impact of the gestational week in which maternal serum samples are collected on the diagnosis of GDM should also be examined. Longitudinal studies may provide more in-depth insights into how omentin levels change throughout pregnancy and their potential predictive value for GDM. Prospective studies investigating the effects of omentin levels on the development and progression of GDM are crucial for a better understanding of this complex relationship.

GDM is a carbohydrate intolerance condition that occurs during pregnancy and can have significant effects on the health of both the mother and the fetus. Studies on the role of adipokines, especially vaspin, in the development of GDM suggest the potential of these substances to be used as biomarkers in diagnostic and therapeutic strategies [26, 27, 28]. However, the results of studies examining the relationship between vaspin levels and GDM in the literature have been contradictory [26, 27, 28, 29, 30].

Lal et al. [28], Tang et al. [29], and Jia et al. [30] found significantly higher serum vaspin levels in women with GDM compared to controls, suggesting an association between vaspin and GDM. In contrast, Mierzyński et al. [31] and Huo et al. [32] found significantly lower serum vaspin levels in women with GDM compared to controls. These conflicting findings highlight the complexity of vaspin’s role, as well as that of other adipokines, in the pathophysiology of GDM. Indeed, Gkiomisi et al. [26] and Stepan et al. [33] questioned the utility of vaspin as an independent marker for GDM. Miehle et al. [34] examined vaspin levels longitudinally according to gestational age and found that vaspin levels were lower in women between 24 and 30 weeks of gestation compared to nonpregnant women. These studies have shown that vaspin levels vary with gestational age but decrease at similar rates in both women with and without GDM. Furthermore, no significant relationship was found between vaspin levels and glucose metabolism, insulin resistance, or inflammation. These findings suggest that vaspin have limited utility as a biomarker for the diagnosis or treatment of GDM. In our study, no significant difference was found in vaspin levels between pregnant patients with and without GDM. This suggests that vaspin may not be an effective biomarker for GDM. All the findings obtained indicate that the relationship between vaspin and GDM is more complex than expected, and a better understanding of this relationship may be important in developing potential strategies for the early diagnosis and management of GDM. When the results of our study are combined with the contradictory findings in the literature, it becomes clear that vaspin may not be a reliable independent biomarker for GDM. Therefore, comprehensive studies with larger samples and including more adipokine types are needed to fully understand the role of vaspin in GDM.

The literature on the relationship between circulating visfatin levels and GDM is also inconsistent. In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Jiang et al. [35] reported no significant difference in circulating visfatin levels between women with GDM and those with normal glucose tolerance, concluding that visfatin levels are not independently associated with GDM. Similarly, Zhang et al. [36] reported that visfatin was not directly associated with GDM, but may be associated with maternal overweight/obesity through its connection to GDM. Torun et al. [37] also found no significant difference in visfatin levels between pregnant patients with GDM and those without GDM.

Bawah et al. [38] suggested that high visfatin levels (hypervisfatinemia) may predict the development of GDM and therefore could serve as a useful predictive indicator for the condition. However, Radzicka-Mularczyk et al. [39] found that serum visfatin levels were increased in GDM patients with high BMI values, and this increase was positively correlated with glycated hemoglobin. In contrast, our study found no significant difference in visfatin levels between pregnant patients with GDM and those without GDM, suggesting that visfatin does not play an independent role in the development of GDM. Miehle et al. [34] studied visfatin levels longitudinally during pregnancy and reported that visfatin levels peaked between 19 and 26 weeks gestation but decreased between 27 and 34 weeks. The findings of our study suggest that the role of visfatin in the pathophysiology of GDM is more complex than expected. Considering the inconsistencies in the literature and our findings, further research is needed to fully understand the role of visfatin in GDM. This research should particularly focus on its interactions with other metabolic factors and its behavior at different stages of pregnancy. Therefore, further research is warranted to develop potential strategies for the early diagnosis and management of GDM.

This study is an important step toward a better understanding of the relationships between GDM and adipokines. However, further research is needed to determine the precise roles of these hormones in the pathophysiology of GDM. Future studies may support the findings of this study and further elucidate the potential roles of adipokines in the early diagnosis and management of GDM. The cross-sectional design of this study limits our ability to determine the temporal relationships between adipokine levels and the development of GDM. Therefore, prospective cohort studies that monitor adipokine levels throughout pregnancy are necessary, as they may provide clearer insights into the roles of these hormones in the onset and progression of GDM. Despite its valuable findings, this study has several limitations. Its single-center design may limit the generalizability of the results to other populations and healthcare settings. Although the sample size was sufficient to detect significant differences in omentin levels between GDM patients and controls, it may not fully capture the variability and complexity of adipokine profiles in larger populations. Furthermore, this study focused solely on omentin, vaspin, and visfatin, potentially overlooking other adipokines that may play a role in the pathophysiology of GDM. Therefore, future studies involving multicenter collaborations and larger, more diverse cohorts are needed to confirm our findings. Furthermore, longitudinal studies monitoring adipokine levels throughout pregnancy may provide deeper insights into their dynamic roles in the development and progression of GDM. Finally, examining the interactions between adipokines and other metabolic and inflammatory markers may further elucidate the complex biological network underlying GDM.

In our study, omentin levels, which are typically reported to be low in pregnant patients with GDM according to the literature, were found to be significantly higher. This finding suggests that omentin may have a different and more complex role in the pathophysiology of GDM than previously expected. This increase in omentin levels may be interpreted as a protective response by the body against insulin resistance and inflammation. Additional studies are needed to better understand the role of adipokines, in particular omentin, in the pathophysiology of GDM. Vaspin and visfatin levels did not show a significant difference between pregnant patients with GDM and those without GDM. This finding reinforces the uncertainty regarding the utility of these adipokines as independent biomarkers for GDM. Our results indicate that omentin may be a potentially important biomarker for understanding the biochemical processes of GDM, while the diagnostic value of vaspin and visfatin warrants further investigation. It is crucial for future studies to be conducted on a larger scale, using longitudinal, single-factor, and multifactorial analyses to evaluate the effects of omentin, vaspin, and visfatin in the early diagnosis and management of GDM.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

MY and YA were responsible for data collection and writing the manuscript. NB and SA performed data analysis, statistical evaluation, and contributed to the study design. SA also formulated the hypotheses and contributed significantly to the manuscript writing. DB critically evaluated and revised the manuscript. FZK and LS participated in data collection and evaluation. IB contributed to data collection. All authors were involved in the editorial revisions of the manuscript, read and approved the final version, and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

The study was approved by the Siirt University ethics committee in Turkey (2022/09/01/01). The study was performed according to the standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Data is obtained from The Siirt Training and Research Hospital Obstetrics and Gynecology clinic, the women gave informed consent that their data in The Siirt Training and Research Hospital obstetrics and Gynecology can be used in research. Informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardians.

I would like to thank the information processor Yücel Tan, who worked on the hospital information system data infrastructure.

This research received no external funding.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

Publisher’s Note: IMR Press stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.